Abstract

Bcl-2 family proteins play a crucial role in tissue homeostasis and apoptosis (programmed cell death). Bid is a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, promoting cell death when activated by caspase-8. Following an NMR-based approach (structure–activity relationships by interligand NOE) we were able to identify two chemical fragments that bind on the surface of Bid. Covalent linkage of the two fragments led to high-affinity bidentate derivatives. In vitro and in-cell assays demonstrate that the compounds prevent tBid translocation to the mitochondrial membrane and the subsequent release of proapoptotic stimuli and inhibit neuronal apoptosis in the low micromolar range. Therefore, by using a rational chemical–biology approach, we derived antiapoptotic compounds that may have a therapeutic potential for disorders associated with Bid activation, e.g., neurodegenerative diseases, cerebral ischemia, or brain trauma.

Keywords: apoptosis, drug discovery, neurodegeneration

Programmed cell death (1–3) is a process associated with several pathologies such as neurodegenerative diseases, spinal cord injury, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and brain ischemia (4–6). Bid (7, 8) is a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family proteins, and its altered expression accounts for onset and propagation of these pathologies (4–6). The sequence of events leading to programmed cell death has been well characterized in nonneuronal cells (1–3), where Bid provides one mechanism by which TNF–Fas family death receptor activation is linked to downstream events (9). These death receptors activate caspase-8, which cleaves Bid to its truncated active form, tBid (8). tBID targets the outer mitochondrial membrane and induces conformational changes in Bak and Bax (10), which results in the release of proapoptotic stimuli such as Smac and cytochrome c (11). Cytochrome c, together with APAF-1 and caspase-9, form the apoptosome complex, which results in the activation of caspase-3 and other effector caspases, which ultimately cause cell death (12).

Recent studies clearly point to Bid as a mediator upstream of mitochondria in neuronal death after cerebral ischemia (13). By using an in vivo model of mild focal cerebral ischemia and an in vitro neuronal oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD) that favors apoptotic cell death, we showed that Bid is a critical mediator of ischemic cell death within the CNS (13). Reduced cell death was observed in highly enriched neuronal cultures from Bid−/− mice after OGD and reduced ischemic brain injury in mutant mice with a deletion in Bid. It was also found that both Bid and caspase-3 are activated in an ischemic brain and in cultured neurons after OGD.

The results generated by using Bid−/− mice demonstrate convincingly that Bid plays a prominent role in acute CNS injury. Phenotypically, these mutant mice do not have any CNS developmental defect (11) or any difference in microscopic or macroscopic CNS morphologies, as compared with WT mice. It can be concluded that Bid promotes death in neurons after OGD in vitro and in the brain after focal cerebral ischemia in vivo. Because Bid is strategically located upstream of mitochondria and caspase-3 processing, Bid presents an even more attractive target than caspases for CNS diseases in which apoptotic cell death is prominent.

Although it is a valuable drug target, the design of Bid inhibitors is not a trivial task and is certainly not amenable to conventional high-throughput screening techniques. We report on the use of an innovative approach based on a fragment assembly strategy that resulted in drug-like compounds that bind to Bid and effectively inhibit its proapoptotic activity in a number of in vitro and cell-based assays with neuronal cells.

Results and Discussion

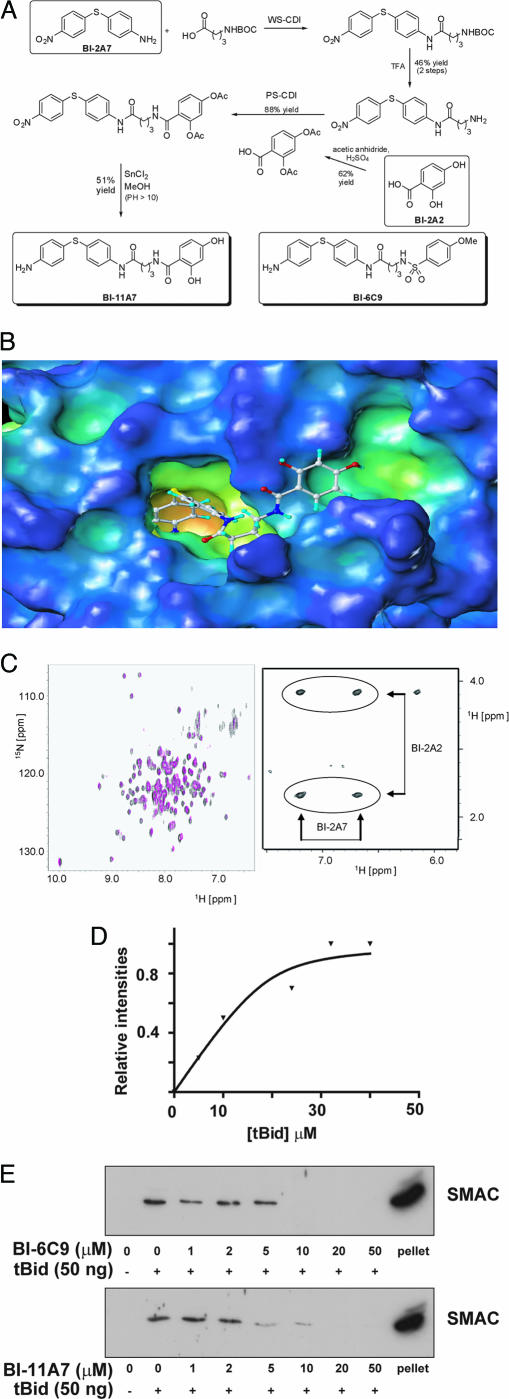

Recent years have witnessed the development of a number of chemical fragment-based approaches to inhibitor design and drug discovery that have been applied to even unconventional and challenging drug targets such as those involving protein–protein interactions (14–17). Along these lines of research, we recently described a powerful NMR method that led us to the identification of high-affinity ligands for given targets by linking low-affinity fragments (18). This task is achieved by screening a small but diverse library of compounds by NMR (19, 20), a technique that allows the detection of even weak binders. The approach, structure–activity relationships by interligand NOE (ILOEs) (18, 21), permits the identification of pairs of small molecules that sit in adjacent sites on the surface of a given protein (Fig. 1). Accordingly, we were able to isolate pairs of low-affinity (millimolar) fragments (namely compounds BI-2A2 and BI-2A7; Fig. 2 A and C Right) that bind simultaneously to a deep hydrophobic crevice on the surface of Bid. The compounds were then subjected to docking analysis into the 3D structure of the protein to direct the synthesis of bidentate compounds. However, because of the poor resolution of the available NMR structures of Bid (22, 23), we opted for the systematic synthesis of bidentate compounds with linkers of various length (one- to five-carbon chains). Synthesis of BI-11A7 is described in Fig. 2A. The first peptide bond formation was aided by 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (24) by using as starting materials 4-amino-4′-nitrodiphenyl sulfide (Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 4-[(tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino]butanoic acid (Boc-GABA-OH; Novabiochem, EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Stirring the reaction mixture at room temperature resulted in the corresponding Boc-protected amine, which was deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid to give the free amine in good yields (Fig. 2A). The latter was reacted with 2,4-diacetoxybenzoic acid in the presence of N-cyclohexylcarbodiimide-N′-propylmethyl polystyrene (Argonaut Technologies, San Diego, CA), and the reaction product was reduced (SnCl2) and deprotected to free hydroxyls, resulting in the final bidentate compound BI-11A7. Compound BI-6C9 (Fig. 2A) was similarly obtained (21), and analogues with different linker lengths (one, two, four, and five carbons) proved less effective in binding Bid in NMR-based assays (21).

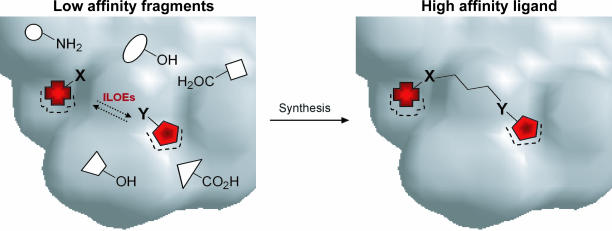

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the structure–activity relationships by an ILOEs approach. Based on the nature of the observed ILOEs, different linkers could be envisioned, with X and Y being one of the following: -CONH-; -NHCO-; SO2NH-; NHSO2-; -O-, CH2-, -S-, and -NH-. The linker could be simply aliphatic or further rigidified by introducing double bonds, cyclic moieties, or aromatic rings.

Fig. 2.

Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro activity of Bid inhibitors. (A) Synthetic scheme for the bidentate compound BI-11A7. (B) Docking of BI-11A7 into the 3D structure of Bid. (C Right) Portion of the 2D 1H,1H NOESY (600-msec mixing time) spectrum of a solution of BI-2A2 and BI-2A7 (1 mM each) in the presence of Bid (10 μM). Circles represent ILOE cross-peaks between the two molecules. (C Left) 2D 15N,1H TROSY spectrum measured with a sample of 0.5 mM tBid (obtained by cleavage of Bid with caspase-8) in the absence (black) and presence (red) of 1 mM BI-11A7. (D) Dose–response curve for compound BI-11A7. The intensity of the compound’s (20 μM) resonance lines was monitored during titration of tBid. The dissociation constant of 1.9 μM is obtained by nonlinear fit of the data. (E) BI-6C9 and BI-11A7 block tBid-induced Smac release from mitochondria isolated from HeLa cells. The first lane represents mitochondria incubated without tBid. All others received 50 ng of tBid without or with bidentate compound.

Molecular docking of BI-11A7 suggests how it may fit in the deep hydrophobic crevice on the surface of Bid (Fig. 2B). To better characterize this interaction we prepared 15N-labeled Bid and acquired 2D 15N,1H TROSY spectra in the absence or presence of BI-11A7 or BI-6C9. Upon addition of the compound several chemical-shift perturbations were observed, with compound BI-11A7 producing the largest shifts (data not shown) compatible with specific binding in the low micromolar range. Interestingly, the shifts are larger when the protein is cleaved by caspase-8, suggesting that BI-11A7 may bind to tBid with higher affinity (Fig. 2C Left). A dose–response curve for the binding of compound BI-11A7 to tBid is resorted in Fig. 2E, where the intensity of the resonance lines of the compound was monitored upon complexation with the target. When the compounds were tested in a similar NMR-based assay against Bcl-XL, an antiapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family with overall topology and structure that is similar to Bid (25), they did not show appreciable binding.

The interaction of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein with the mitochondrial membrane results in the release of apoptogenic factors such as cytochrome c and SMAC (2). When tested side-by-side, BI-11A7 and BI-6C9 are both capable of inhibiting Bid-mediated release of SMAC from mitochondria isolated from HeLa cells (Fig. 2E). However, BI-11A7 is much more effective in this assay when compared with BI-6C9, and it is able to dramatically decrease the release of SMAC at low micromolar concentrations. NMR-derived (Fig. 2D) Kd values for BI-11A7 and BI-6C9 are ≈1.5 μM and 20 μM, respectively, thus showing a good parallel with the in vitro SMAC release assay (Fig. 2E). Therefore, by using our NMR-based approach, we were able to design and synthesize two series of bidentate compounds that bind to Bid (and tBid) and inhibit its activity.

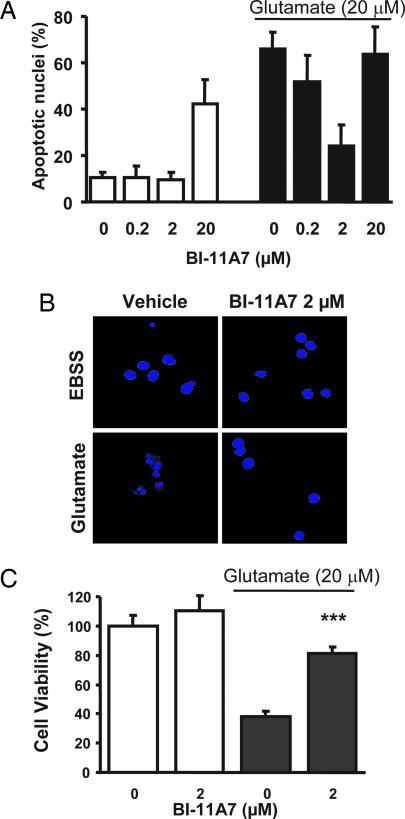

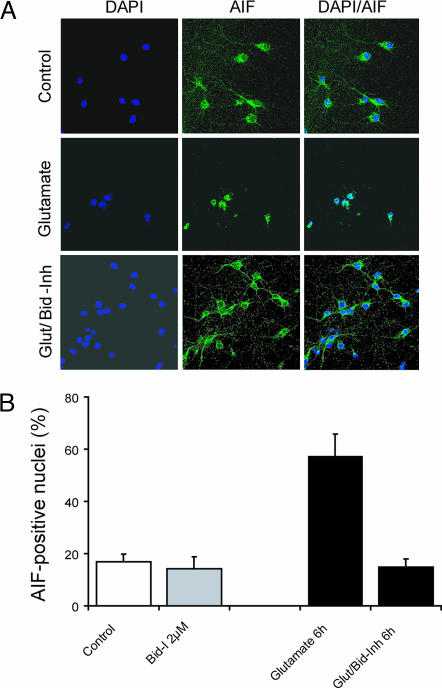

Based on our earlier preliminary observations with BI-6C9, the compound is also capable of preventing tBid-induced apoptosis in transfected HeLa cells (21) and in immortalized HT22 mouse hippocampal neurons (26). To assess whether the compounds would also prevent neuronal cell death in primary cultures, a number of cell-based assays were performed. When tested against primary hippocampal neurons, compound BI-11A7 shows some toxicity at higher concentrations (20 μM), but it displays a remarkable dose-dependent neuroprotective effect in the low micromolar range (0.2–2 μM) (Fig. 3A). Similar results can be observed when using primary cortical neurons (Fig. 3 B and C). Most interestingly, BI-11A7 also prevented nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) in neurons exposed to glutamate (Fig. 4). This finding is in line with our previous findings on neuroprotective effects of BI-6C9 in primary neurons exposed to OGD (27) and in HT22 neurons exposed to glutamate (26). In primary neurons, translocation of AIF from mitochondria to the nucleus occurred within a few hours after OGD and preceded morphological signs of cell death such as DNA fragmentation and nuclear pyknosis (28). It has been well established that AIF can exert cell death in a caspase-independent manner (29), and using siRNA approaches we recently demonstrated a pivotal role for AIF in glutamate- or OGD-induced cell death in neurons (27). Moreover, reduced AIF levels in brain tissue significantly reduced neuronal cell death in models of kainate-induced excitotoxicity (30) and after cerebral ischemia (27) in transgenic Harlequin mice. It is important to note that the observed neuroprotection by AIF gene silencing was similar to protective effects previously established in models relevant to cerebral ischemia in cultured neurons and in mice lacking Bid expression (13) but exceeded the protective effects of caspase inhibitors in parallel experiments. These data underline the important contribution of caspase-independent mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases with prominent features of programmed cell death. Furthermore, our present results with the small-molecule Bid inhibitors in cultured neurons demonstrate an upstream role of Bid in the release of AIF from mitochondria and therefore validate Bid and tBid as promising upstream targets to prevent activation of caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell-death cascades.

Fig. 3.

Cell-based evaluation of Bid inhibitors. Embryonic rat hippocampal (A) or cortical (B) neurons were pretreated with BI-11A7 at the indicated concentrations 1 h before exposure to glutamate (20 μM) in EBSS. After 24 h, apoptotic nuclei were quantified after staining with Hoechst 33342. (C) In a separate experiment, the protective effect of BI-11A7 against glutamate-induced cell death was quantified by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay (mean ± SEM; n = 3). The graphs show mean percentages of apoptotic nuclei (A) or cell viability (C) and SD of five separate dishes per group. ∗∗∗, P < 0.001 compared with glutamate-treated cells (ANOVA and Scheffé test).

Fig. 4.

Cell-based evaluations of Bid inhibitors with primary neuronal cells. (A) Immunostaining of rat embryonic cortical neurons shows translocation of AIF (green fluorescence) to the nucleus 8 h after exposure to glutamate. Pretreatment with BI-11A7 preserves nuclear morphology (blue fluorescence, Hoechst 33342) and prevents AIF translocation. (B) Quantification of AIF-positive nuclei in rat embryonic neurons exposed to glutamate (20 μM) for 8 h. Mean values and SD of four dishes per group are presented.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have reported on the design and synthesis of high-affinity antiapoptotic compounds that selectively target Bid. Our studies not only resulted in chemical tools that can be used to further elucidate the role of Bid in neurodegenerative disorders, but they could also translate into potential lead compounds for further drug development. Finally, our data clearly demonstrate the potential of our approach, structure–activity relationships by ILOEs, in tackling very challenging drug targets. We anticipate being able to apply our general methodology to derive high-affinity ligands against challenging drug targets such as those involved in complex macromolecular interactions.

Materials and Methods

Chemistry.

BI-11A7: 1H NMR (d-DMSO, 300 MHz), 10.06 (s, 1H), 9.92 (s, 1H), 8.58–8.56 (m, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.59 (d, J = 8.4, 2H), 6.30–6.22 (m, 2H), 5.46 (bs, 2H), 3.42–3.35 (m, 2H), 2.36–2.32 (m, 2H), 1.88–1.80 (m, 2H). MALDI-MS: 438 (15, M+ + 1), 437 (10, M+), 362 (20), 320 (35), 304 (30), 282 (95), 273 (100).

Protein Expression and Purification.

Recombinant full-length mouse Bid was produced from a pET-19b (Novagen) plasmid construct containing the entire nucleotide sequence for Bid fused to an N-terminal polyHis tag. Unlabeled Bid was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 in LB medium at 37°C, with an induction period of 3–4 h with 1 mM IPTG. 15N-labeled Bid was similarly produced, with growth occurring in M9 medium supplemented with 0.5 g/liter 15NH4Cl. After cell lysis, soluble Bid was purified over a Hi-Trap chelating column (Amersham Pharmacia) followed by ion-exchange purification with a MonoQ (Amersham Pharmacia) column. Final Bid samples were dialyzed into a buffer appropriate for the subsequent experiments. tBid was produced by cleavage of purified Bid with caspase-8 as reported (31).

Structure–Activity Relationships by ILOEs.

For all NMR experiments, Bid was exchanged into 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.5, and measurements were performed at 30°C. 2D 15N,1H TROSY spectra for Bid were measured with 0.5 mM samples of 15N-labeled Bid. 2D 1H,1H NOESY spectra were acquired with small molecules at a concentration of 1 mM in the presence of 10 μM Bid. All experiments were performed with either a 500-MHz or a 600-MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer equipped with TXI probes. Typical parameters for the 2D 15N,1H TROSY spectra included 1H and 15N π/2 pulse lengths of 11 μsec and 40 μsec, respectively; 1H and 15N sweep widths of 12 ppm and 32 ppm, respectively; 16 scans; 256 indirect acquisition points; and a recycle delay of 1 sec. 2D 1H,1H NOESY spectra were typically acquired with 16 scans for each of 400 indirect points, a 1H π/2 pulse length of 11 μsec, sweep widths of 12 ppm in both dimensions, mixing times of 600 msec (optimized for the detection of ILOEs) (18), and a recycle delay of 1 sec. In all experiments, dephasing of residual water signals was obtained with a WATERGATE sequence. Dose–response curves for compounds were obtained by monitoring the intensity of the compounds’ (at 20 μM) resonance lines upon titration with tBid. The dissociation constant was obtained by nonlinear fit of the data with PRISM according to the equation p = {([To] + [Lo] + Kd) − /2[To], where the parameter p represents the fractional population of bound versus free species at equilibrium, which for fast exchanging ligands is measured as p = (δobs − δfree)/(δsat − δfree), and [To] and [Lo] represent the concentration of target and ligand, respectively (16).

Molecular modeling studies were conducted on a Linux workstation with the software package GOLD version 3.0 (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, U.K.) (32, 33) by using the NMR solution structure of mouse Bid (23). The initial 3D structure of the linked compound was built by using CONCORD (34) as implemented in SYBYL version 7.0 (Tripos, St. Louis, MO). For the docking with GOLD, 100 solutions were generated and ranked according to GoldScore and Chemscore. Surface representations were generated by MOLCAD (35) as implemented in SYBYL.

Experiments with Isolated Mitochondria.

A total of 50 ng of tBid (cleaved by caspase-8) was preincubated with various concentrations of compounds for 15 min at 30°C in HM buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4/250 mM mannitol/10 mM KCl/1.5 mM MgCl/1 mM DTT/1 mM EGTA), and then 50 μg of isolated mitochondria from HCT116 cells was added to a final volume of 50 μl in HM buffer. After a 1-h incubation at 30°C, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was analyzed by SDS/PAGE/immunoblotting by using anti-SMAC antibody.

Experiments with Primary Neuronal Cells.

Primary cultures were obtained from embryonic day 18 rats and cultured in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 5 mM Hepes/1.2 mM glutamine/20 ml/liter B27 (Invitrogen)/ 0.1 mg/ml gentamicin as described previously (27). Glutamate (20 μM) was added in 9- to 10-day-old cultures in EBSS medium (6,800 mg/liter NaCl/400 mg/liter KCl/264 mg/liter CaCl2 × 2H2O/200 mg/liter MgCl2 × 7H2O/2,200 mg/liter NaHCO3/140 mg/liter NaH2PO4 × H2O/10 mM glucose, pH 7.2). Neuronal cell death was quantified after staining the nuclei with the DNA-binding fluorochrome Hoechst 33258 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) or by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay. Immunocytochemistry was performed as described previously (28) with a polyclonal anti-AIF antibody (sc-9416, Santa Cruz; 1:200) followed by incubation with a biotinylated anti-goat IgG antibody (1:200) (Vector Laboratories, Burligame, CA) and Oregon green streptavidin (Molecular Probes). After counterstaining with Hoechst 33342, images were acquired by using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Axiovert, Zeiss) with a ×60 oil immersion objective (514-nm excitation and 535-nm emission for detection of Oregon green and 352-nm excitation and 460-nm emission for detection of Hoechst 33342).

Acknowledgments

We thank Melinda Kiss and Miriam Hoehn for excellent technical support. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Heath Grant R01 HL082574 and Department of Defense Grant DoD-PRO54590.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ILOEs

interligand NOE

- AIF

apoptosis-inducing factor

- OGD

oxygen glucose deprivation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Adams J. M., Cory S. Science. 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross A., McDonnell J. M., Korsmeyer S. J. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed J. C. Oncogene. 1998;17:3225–3236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guegan C., Vila M., Teismann P., Chen C., Onteniente B., Li M., Friedlander R. M., Przedborski S. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002;20:553–562. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plesnila N. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2004;89:15–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0603-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plesnila N., Zinkel S., Amin-Hanjani S., Qiu J., Korsmeyer S. J., Moskowitz M. A. Eur. Surg. Res. 2002;34:37–41. doi: 10.1159/000048885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng Y., Ren X., Yang L., Lin Y., Wu X. Cell. 2003;115:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H., Zhu H., Xu C. J., Yuan J. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata S. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:E143–E145. doi: 10.1038/14094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zha J., Weiler S., Oh K. J., Wei M. C., Korsmeyer S. J. Science. 2000;290:1761–1765. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin X. M., Wang K., Gross A., Zhao Y., Zinkel S., Klocke B., Roth K. A., Korsmeyer S. J. Nature. 1999;400:886–891. doi: 10.1038/23730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou H., Li Y., Liu X., Wang X. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11549–11556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plesnila N., Zinkel S., Le D. A., Amin-Hanjani S., Wu Y., Qiu J., Chiarugi A., Thomas S. S., Kohane D. S., Korsmeyer S. J., Moskowitz M. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:15318–15323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261323298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajduk P. J., Gerfin T., Boehlen J. M., Haberli M., Marek D., Fesik S. W. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:2315–2317. doi: 10.1021/jm9901475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitty A., Kumaravel G. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:112–118. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0306-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pellecchia M. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:961–971. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pellecchia M., Becattini B., Crowell K. J., Fattorusso R., Forino M., Fragai M., Jung D., Mustelin T., Tautz L. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2004;8:597–611. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becattini B., Pellecchia M. Chemistry. 2006;12:2658–2662. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fejzo J., Lepre C. A., Peng J. W., Bemis G. W., Ajay, Murcko M. A., Moore J. M. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:755–769. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shuker S. B., Hajduk P. J., Meadows R. P., Fesik S. W. Science. 1996;274:1531–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becattini B., Sareth S., Zhai D., Crowell K. J., Leone M., Reed J. C., Pellecchia M. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou J. J., Li H., Salvesen G. S., Yuan J., Wagner G. Cell. 1999;96:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonnell J. M., Fushman D., Milliman C. L., Korsmeyer S. J., Cowburn D. Cell. 1999;96:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheehan J. C., Preston J., Cruickshank P. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:2492–2493. doi: 10.1021/ja01089a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sattler M., Liang H., Nettesheim D., Meadows R. P., Harlan J. E., Eberstadt M., Yoon H. S., Shuker S. B., Chang B. S., Minn A. J., et al. Science. 1997;275:983–986. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landshamer S., Hoehn M., Becattini B., Pellecchia M., Plesnila N., Culmsee C. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2006;372:78. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Culmsee C., Zhu C., Landshamer S., Becattini B., Wagner E., Pellecchia M., Blomgren K., Plesnila N. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:10262–10272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2818-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plesnila N., Zhu C., Culmsee C., Groger M., Moskowitz M. A., Blomgren K. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:458–466. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cregan S. P., Fortin A., MacLaurin J. G., Callaghan S. M., Cecconi F., Yu S. W., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L., Park D. S., Kroemer G., Slack R. S. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:507–517. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheung E. C., Melanson-Drapeau L., Cregan S. P., Vanderluit J. L., Ferguson K. L., McIntosh W. C., Park D. S., Bennett S. A., Slack R. S. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:1324–1334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4261-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schendel S. L., Azimov R., Pawlowski K., Godzik A., Kagan B. L., Reed J. C. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21932–21936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones G., Willett P., Glen R. C. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones G., Willett P., Glen R. C., Leach A. R., Taylor R. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearlman R. S. CONCORD, distributed by Tripos (St. Louis). 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teschner M., Henn C., Vollhardt H., Reiling S., Brickmann J. J. Mol. Graphics. 1994;12:98–105. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(94)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]