Abstract

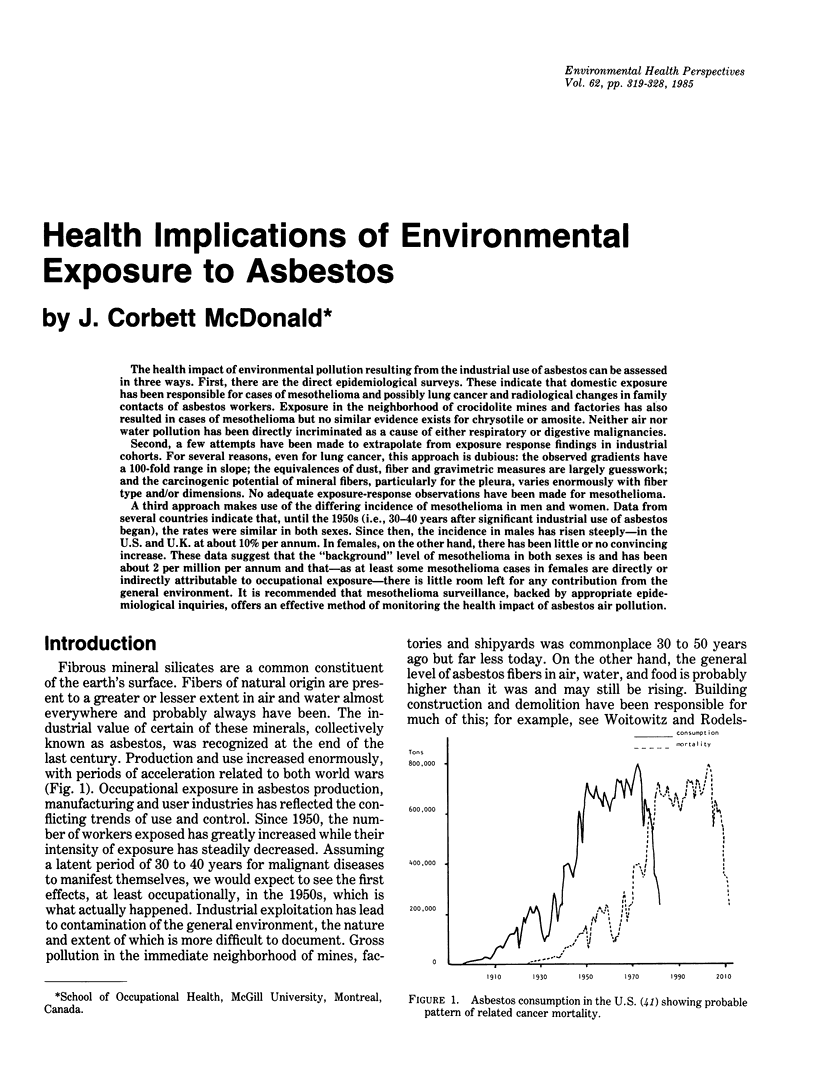

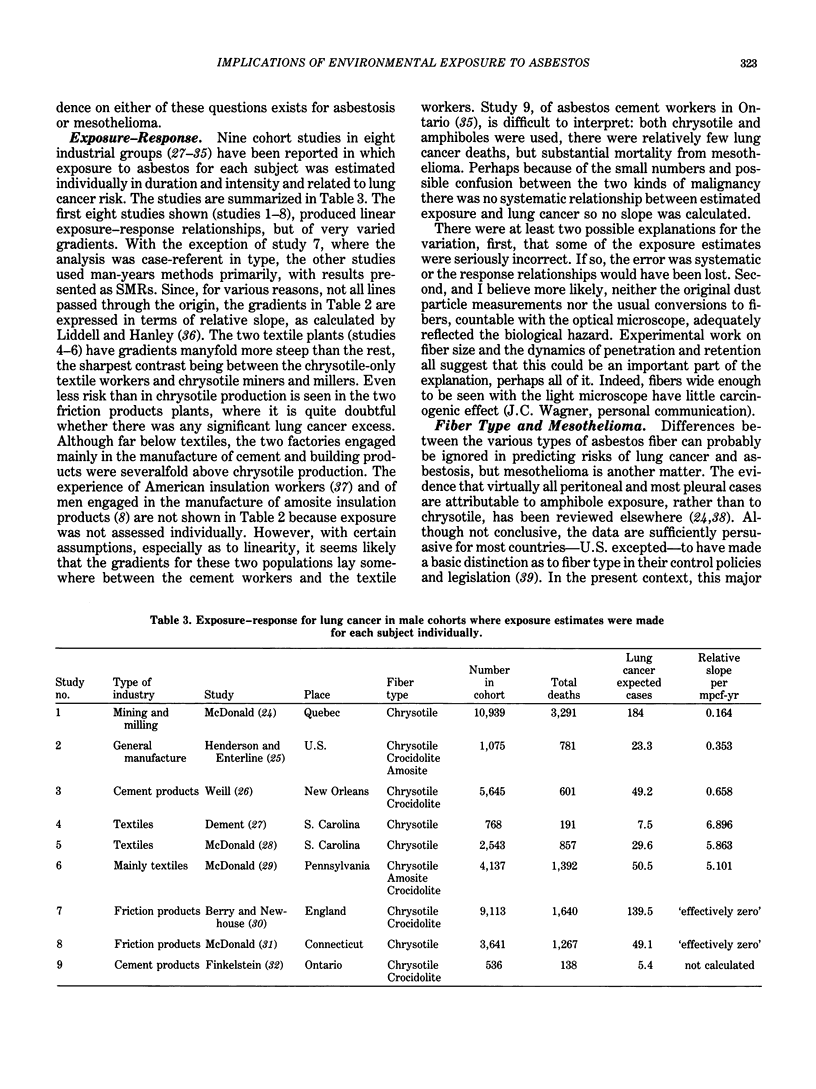

The health impact of environmental pollution resulting from the industrial use of asbestos can be assessed in three ways. First, there are the direct epidemiological surveys. These indicate that domestic exposure has been responsible for cases of mesothelioma and possibly lung cancer and radiological changes in family contacts of asbestos workers. Exposure in the neighborhood of crocidolite mines and factories has also resulted in cases of mesothelioma but no similar evidence exists for chrysotile or amosite. Neither air nor water pollution has been directly incriminated as a cause of either respiratory or digestive malignancies. Second, a few attempts have been made to extrapolate from exposure response findings in industrial cohorts. For several reasons, even for lung cancer, this approach is dubious: the observed gradients have a 100-fold range in slope; the equivalences of dust, fiber and gravimetric measures are largely guesswork; and the carcinogenic potential of mineral fibers, particularly for the pleura, varies enormously with fiber type and/or dimensions. No adequate exposure-response observations have been made for mesothelioma. A third approach makes use of the differing incidence of mesothelioma in men and women. Data from several countries indicate that, until the 1950s (i.e., 30-40 years after significant industrial use of asbestos began), the rates were similar in both sexes. Since then, the incidence in males has risen steeply--in the U.S. and U.K. at about 10% per annum. In females, on the other hand, there has been little or no convincing increase. These data suggest that the "background" level of mesothelioma in both sexes is and has been about 2 per million per annum and that--as at least some mesothelioma cases in females are directly or indirectly attributable to occupational exposure--there is little room left for any contribution from the general environment. It is recommended that mesothelioma surveillance, backed by appropriate epidemiological inquiries, offers an effective method of monitoring the health impact of asbestos air pollution.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson H. A., Lilis R., Daum S. M., Selikoff I. J. Asbestosis among household contacts of asbestos factory workers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330:387–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb18741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckman L., Rubino R. A., Christine B. Asbestos and mesothelioma incidence in Connecticut. J Air Pollut Control Assoc. 1977 Feb;27(2):121–126. doi: 10.1080/00022470.1977.10470400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dement J. M., Harris R. L., Jr, Symons M. J., Shy C. Estimates of dose-response for respiratory cancer among chrysotile asbestos textile workers. Ann Occup Hyg. 1982;26(1-4):869–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmes P. C., Simpson J. C. The clinical aspects of mesothelioma. Q J Med. 1976 Jul;45(179):427–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterline P. E. Cancer produced by nonoccupational asbestos exposure in the United States. J Air Pollut Control Assoc. 1983 Apr;33(4):318–322. doi: 10.1080/00022470.1983.10465580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterline P. E. Extrapolation from occupational studies: a substitute for environmental epidemiology. Environ Health Perspect. 1981 Dec;42:39–44. doi: 10.1289/ehp.814239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterline P. E., Henderson V. Type of asbestos and respiratory cancer in the asbestos industry. Arch Environ Health. 1973 Nov;27(5):312–317. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1973.10666386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein M. M. Mortality among long-term employees of an Ontario asbestos-cement factory. Br J Ind Med. 1983 May;40(2):138–144. doi: 10.1136/oem.40.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. Methodological problems in ecologic studies of the asbestos--cancer relationship. Environ Res. 1981 Jun;25(1):35–49. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(81)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond E. C., Garfinkel L., Selikoff I. J., Nicholson W. J. Mortality experience of residents in the neighborhood of an asbestos factory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330:417–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb18743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J., Weill H. Lung cancer risk associated with manufacture of asbestos-cement products. IARC Sci Publ. 1980;(30):627–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn H. C., Meigs J. W., Teta M. J., Flannery J. T. The influence of occupational and environmental asbestos exposure on the incidence of malignant mesothelioma in Connecticut. IARC Sci Publ. 1980;(30):655–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell F. D., Hanley J. A. Relations between asbestos exposure and lung cancer SMRs in occupational cohort studies. Br J Ind Med. 1985 Jun;42(6):389–396. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.6.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieben J., Pistawka H. Mesothelioma and asbestos exposure. Arch Environ Health. 1967 Apr;14(4):559–563. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1967.10664792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

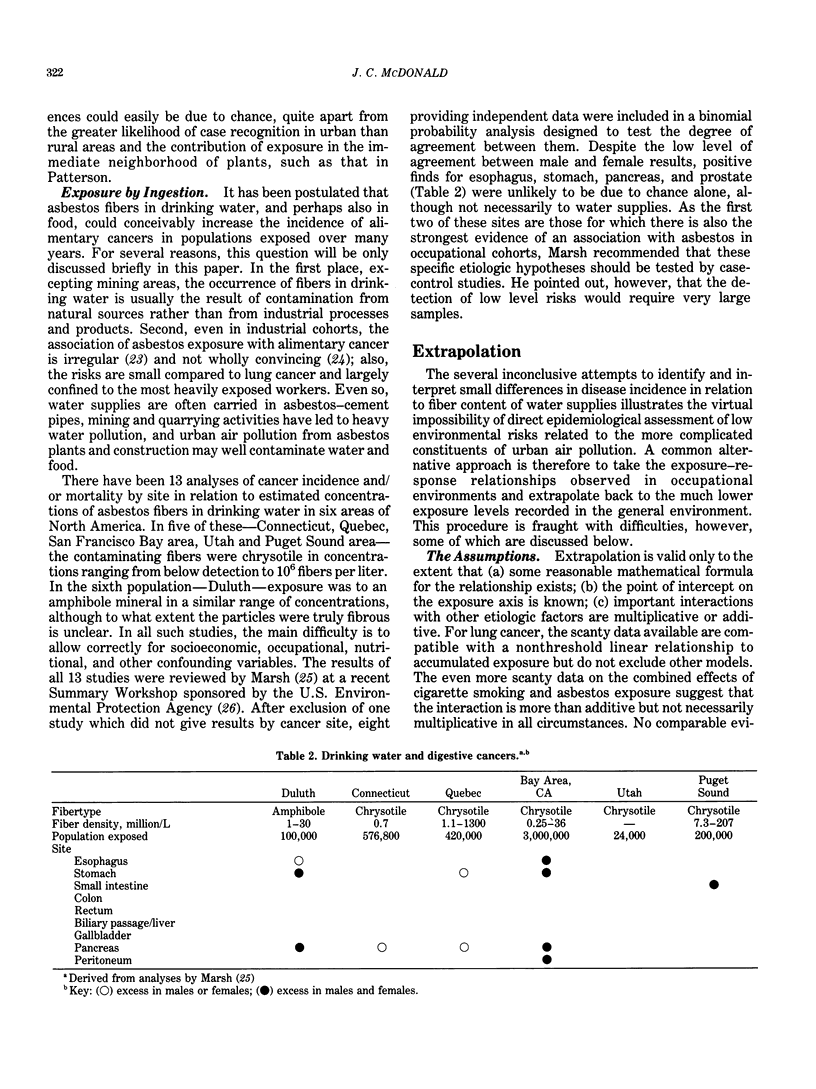

- Marsh G. M. Critical review of epidemiologic studies related to ingested asbestos. Environ Health Perspect. 1983 Nov;53:49–56. doi: 10.1289/ehp.835349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. D., Fry J. S., Woolley A. J., McDonald J. C. Dust exposure and mortality in an American chrysotile asbestos friction products plant. Br J Ind Med. 1984 May;41(2):151–157. doi: 10.1136/oem.41.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. D., Fry J. S., Woolley A. J., McDonald J. C. Dust exposure and mortality in an American factory using chrysotile, amosite, and crocidolite in mainly textile manufacture. Br J Ind Med. 1983 Nov;40(4):368–374. doi: 10.1136/oem.40.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. D., Fry J. S., Woolley A. J., McDonald J. Dust exposure and mortality in an American chrysotile textile plant. Br J Ind Med. 1983 Nov;40(4):361–367. doi: 10.1136/oem.40.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. D., McDonald J. C. Malignant mesothelioma in North America. Cancer. 1980 Oct 1;46(7):1650–1656. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801001)46:7<1650::aid-cncr2820460726>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. D. Mesothelioma registries in identifying asbestos hazards. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330:441–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb18746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. C., Liddell F. D., Gibbs G. W., Eyssen G. E., McDonald A. D. Dust exposure and mortality in chrysotile mining, 1910-75. Br J Ind Med. 1980 Feb;37(1):11–24. doi: 10.1136/oem.37.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. C. Mineral fibres and cancer. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1984 Apr;13(2 Suppl):345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse M. L., Thompson H. Epidemiology of mesothelial tumors in the London area. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1965 Dec 31;132(1):579–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb41138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W. J., Rohl A. N., Weisman I., Selikoff I. J. Environmental asbestos concentrations in the United States. IARC Sci Publ. 1980;(30):823–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurminen M. The epidermiologic relationship between pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1975 Jun;1(2):128–137. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampalon R., Siemiatycki J., Blanchet M. Pollution environnementale par l'amiante et santé publique au Québec. Union Med Can. 1982 May;111(5):475-82, 487-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto J., Seidman H., Selikoff I. J. Mesothelioma mortality in asbestos workers: implications for models of carcinogenesis and risk assessment. Br J Cancer. 1982 Jan;45(1):124–135. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino G. F., Piolatto G., Newhouse M. L., Scansetti G., Aresini G. A., Murray R. Mortality of chrysotile asbestos workers at the Balangero Mine, Northern Italy. Br J Ind Med. 1979 Aug;36(3):187–194. doi: 10.1136/oem.36.3.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman H., Selikoff I. J., Hammond E. C. Short-term asbestos work exposure and long-term observation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330:61–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb18710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selikoff I. J., Hammond E. C., Seidman H. Mortality experience of insulation workers in the United States and Canada, 1943--1976. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330:91–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb18711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teta M. J., Lewinsohn H. C., Meigs J. W., Vidone R. A., Mowad L. Z., Flannery J. T. Mesothelioma in Connecticut, 1955-1977. Occupational and geographic associations. J Occup Med. 1983 Oct;25(10):749–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER J. C., SLEGGS C. A., MARCHAND P. Diffuse pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure in the North Western Cape Province. Br J Ind Med. 1960 Oct;17:260–271. doi: 10.1136/oem.17.4.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell F., Scott J., Grimshaw M. Relationship between occupations and asbestos-fibre content of the lungs in patients with pleural mesothelioma, lung cancer, and other diseases. Thorax. 1977 Aug;32(4):377–386. doi: 10.1136/thx.32.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]