Abstract

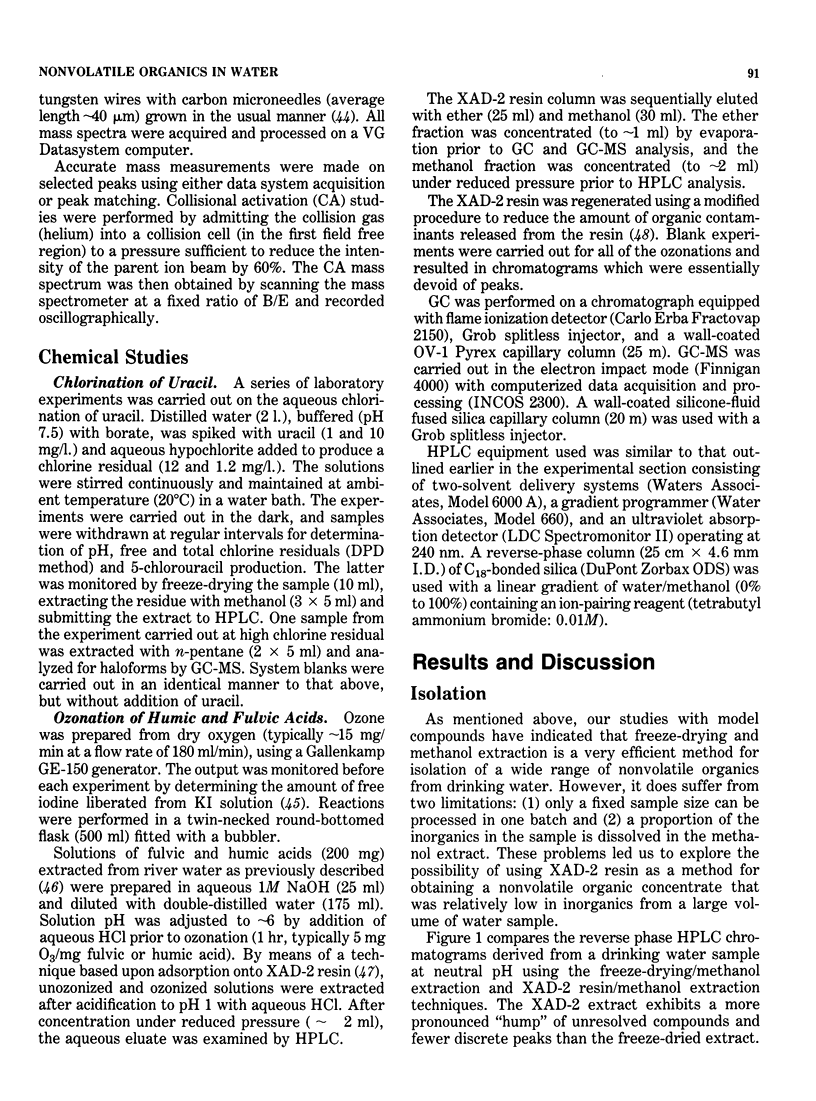

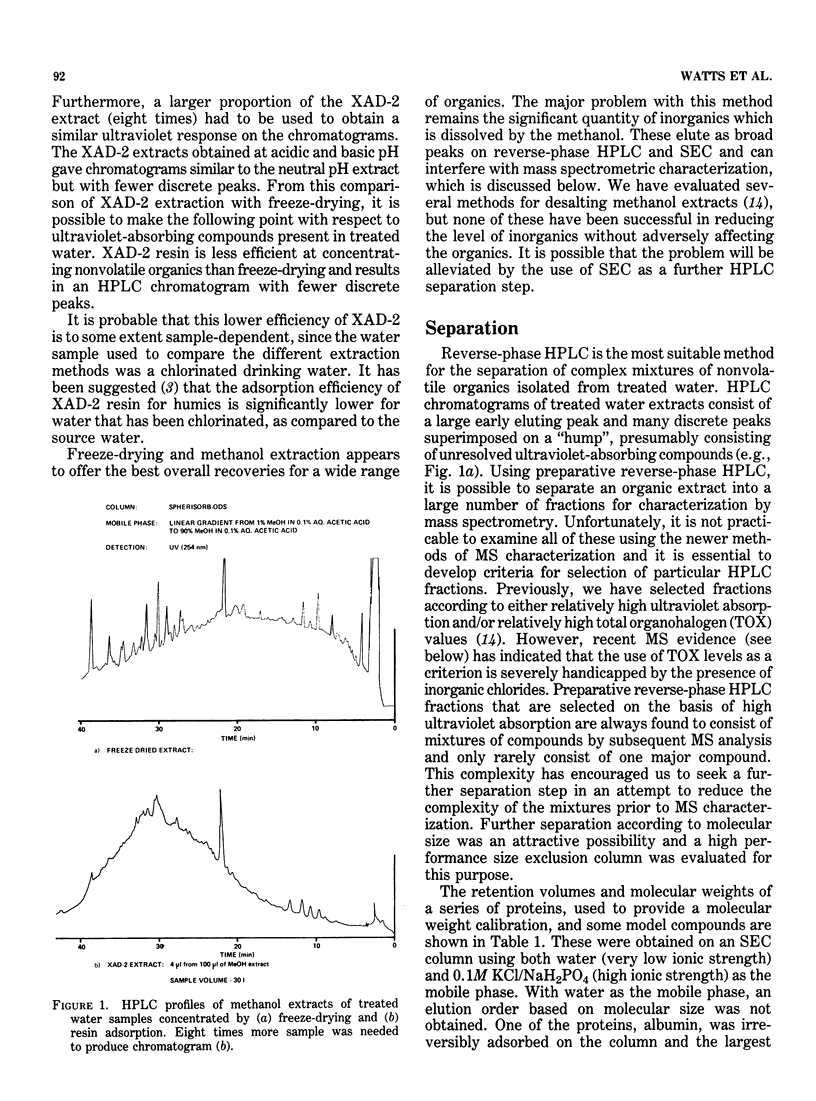

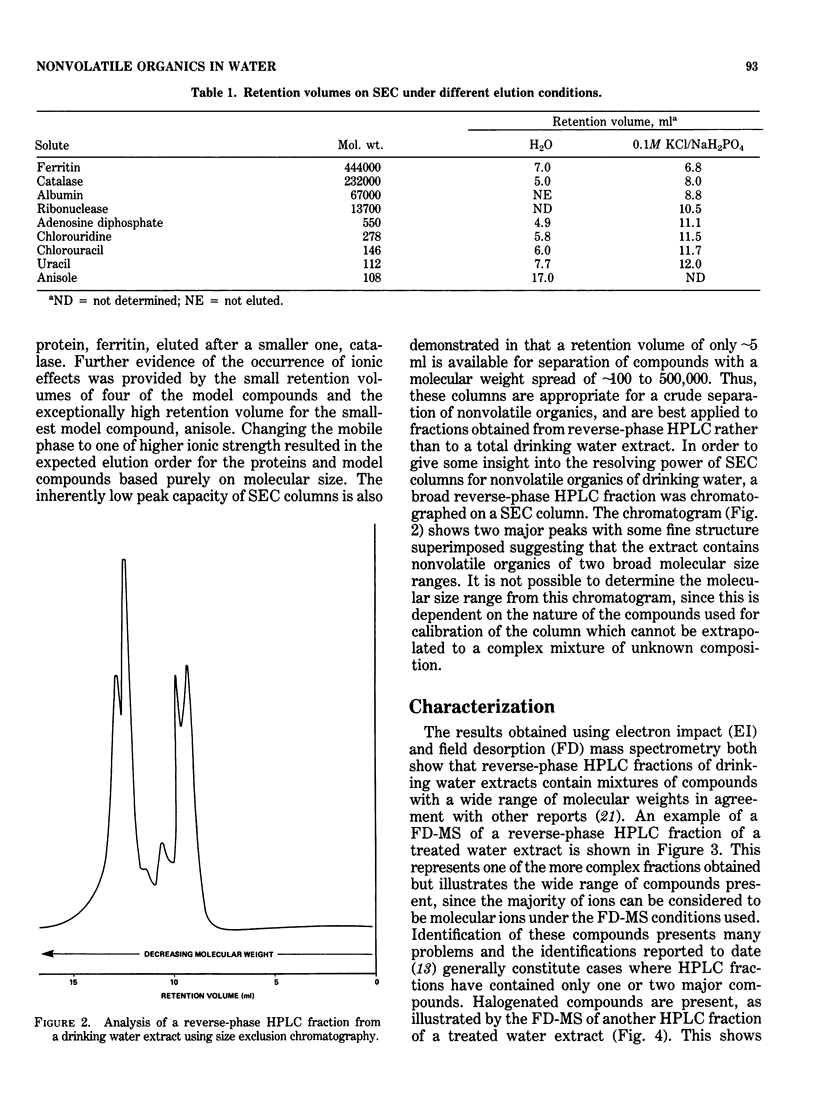

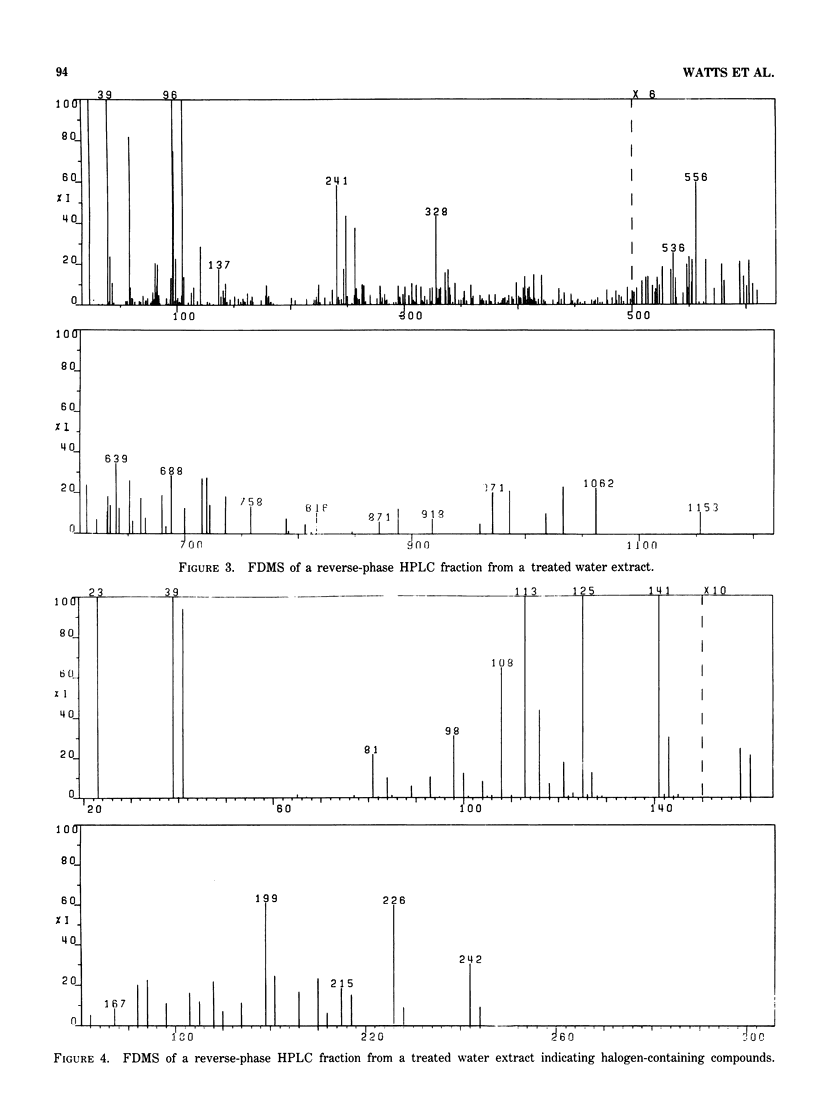

Over the past decade much information has been published on the analysis of organics extracted from treated water. Certain of these organics have been shown to be by-products of the chlorination disinfection process and to possess harmful effects at high concentrations. This has resulted in increased interest in alternative disinfection processes, particularly ozonation. The data on organics had been largely obtained by using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, which is only capable of analyzing, at best, 20% of the organics present in treated water. Research in key areas such as mutagenicity testing of water and characterization of chlorination and ozonation by-products has emphasized the need for techniques suitable for analysis of the remaining nonvolatile organics. Several methods for the isolation of nonvolatile organics have been evaluated and, of these, freeze-drying followed by methanol extraction appears the most suitable. Reverse-phase HPLC was used for separation of the methanol extract, but increased resolution for separation of the complex mixtures present is desirable. In this context, high resolution size exclusion chromatography shows promise. Characterization of separated nonvolatiles is possible by the application of state-of-the-art mass spectrometric techniques. Results obtained by these techniques have shown that the nonvolatile organic fraction of chlorinated drinking water consists of many discrete compounds. Among these, some of the chlorinated compounds are almost certainly by-products of disinfection. Studies of the by-products of ozonation of fulvic and humic acids isolated from river waters have indicated a similar proportion of nonvolatile organics. Further, ozonation can result in the release of compounds that are trapped in the macromolecules.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Junk G. A., Richard J. J., Grieser M. D., Witiak D., Witiak J. L., Arguello M. D., Vick R., Svec H. J., Fritz J. S., Calder G. V. Use of macroreticular resins in the analysis of water for trace organic contaminants. J Chromatogr. 1974 Nov 6;99(0):745–762. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)90900-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loper J. C. Mutagenic effects of organic compounds in drinking water. Mutat Res. 1980 Nov;76(3):241–268. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(80)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]