Abstract

During mitosis, microtubules not only grow fast, but also have a high rate of catastrophe. This is achieved in part by the activity of the MAP, XMAP215, which can stimulate the growth rate of microtubules without fully inhibiting the function of the catastrophe-kinesin XKCM1. We do not know whether this activity is particular to XMAP215, or is a general property of all MAPs. Here, we compare the activities of XMAP215 with the neuronal MAP tau, in opposing the destabilizing activity of the non-conventional kinesin XKCM1. We show that tau is a much more potent inhibitor of XKCM1 than XMAP215. Because tau completely suppresses XKCM1 activity, even at low concentrations, the combination of tau and XKCM1 is unable to generate mitotic microtubule dynamics.

Keywords: mitotic spindle, microtubule, MAPs, XMAP215, tau, MCAK

1. Introduction

Microtubules assemble by polymerization of αβ-tubulin dimers. Polymerization is a polar process that reflects the polarity of the tubulin dimer, which in turn dictates the polarity of the microtubule. Microtubules are nucleated at centrosomes and grow out with their plus ends leading into the cytoplasm. It is thought that plus end dynamics are regulated primarily through regulation of the catastrophe rate of plus ends (Howard & Hyman 2003). A popular idea for formation of mitotic spindles is termed ‘search and capture’. In this model, microtubules grow out randomly from a centrosome. If chromosomes capture them, they are stabilized. If not, they undergo catastrophes and shrink back to the centrosome (Mitchison & Kirschner 1984a,b). Such models depend on having a high growth rate and a high catastrophe rate. If the growth rate is too low, the microtubules will take too long to reach the chromosomes. If the catastrophe rate is too low, the microtubules will not turn over fast enough if they fail to make a productive interaction with chromosomes (Kinoshita et al. 2002). In vitro, the rate of catastrophe is a function of the concentration of tubulin. At 15 μM tubulin, microtubules grow at 1.5 μm min−1 and few catastrophes are seen (Mitchison & Kirschner 1984a; Walker et al. 1991). In vivo, the tubulin concentration is 25 μM, microtubules grow at about 10 μm min−1, and yet microtubules still have a high rate of catastrophe (Belmont et al. 1990; Tournebize et al. 1997). We have recently shown that in Xenopus egg extracts, high growth rate and high catastrophe rates can be reconstituted in vitro using two proteins with opposed activity: XKCM1, a member of the MCAK family, and XMAP215, a microtubule-associated protein (Kinoshita et al. 2001). The MCAK family of proteins are non-conventional kinesins which use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to destabilize microtubule ends (Desai et al. 1999). XMAP215 is a member of a conserved family of proteins, defined by the presence of HEAT repeats in the N terminus (Ohkura et al. 2001).

An interesting question that was raised by this work was the extent to which inhibition of XKCM1 by XMAP215 is a specific property of XMAP215, or a general property of microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). One group of classical MAPs includes tau, MAP2 and MAP4. These MAPs contain a conserved tubulin-binding domain composed of a repeated motif (Lewis et al. 1988; West et al. 1991). This group of MAPs has been shown to stabilize microtubules in vivo and in vitro. However, their ability to oppose the activities of MCAK family members has not been studied. Here, we compare the activity of XMAP215 with the activity of tau in opposing the activity of XKCM1.

2. Materials and methods

Tubulin was prepared by the method of Weingarten et al. (1975) with the modifications described by Mitchison & Kirschner (1984b). Tau was prepared as described (Drechsel et al. 1992). XMAP215 and XKCM1 were prepared as described in the supplementary material of Kinoshita et al. (2001).

Dynamic microtubules were assayed according to protocol as described (Kinoshita et al. 2001).

For the fixed time-point assay, tubulin containing trace amounts of Cy3-labelled tubulin was pre-spun for 6 min at 2 °C in a TLA 100 rotor at 100 000 rpm in a Beckman Optima Ultracentrifuge to remove aggregates. All components were mixed together on ice and then incubated for 5 min at 30 °C. The reaction mix was fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and then spun onto pre-cleaned polylysinated cover-slips through a 25% glycerol cushion. After washing the interface with 1% Triton X 100, the cushion was removed and the cover-slips were mounted with Mowiol and observed by epifluorescence. Epifluorescent images were captured with a Zeiss Plan Apochroma 100X NA 1.4 on a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope running the Metamorph system. The lengths of at least 100 microtubules were measured for each datapoint and the values presented represent the mean±the standard error of the mean.

3. Results and discussion

(a) XMAP215 and tau inhibit the microtubule destabilizing activity of XKCM1/MCAK

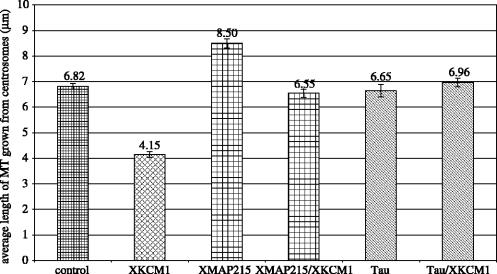

To analyse the role of these microtubule associated proteins in microtubule dynamics, we expressed XMAP215 in baculovirus, and tau in bacteria, and purified them using published procedures (Drechsel et al. 1992; Kinoshita et al. 2001). We wanted to compare the ability of XMAP215 and tau to inhibit the microtubule destabilizing activity of XKCM1. We set up a fixed time-point assay in which microtubules were grown from centrosomes in the presence of Cy3-tubulin. After 5 min at 30 °C, the centrosome-nucleated microtubules were fixed with glutaraldehyde and the length of microtubules was quantified. The results are shown in figure 1. For all experiments, we used 110 nM XKCM1. Addition of XKCM1 reduces the length of microtubules grown in the absence of either MAP. We first examined whether 200 nM XMAP215 could suppress the microtubule destabilizing activity of XKCM1 in this assay. As expected (Kinoshita et al. 2001), XMAP215 can suppress the activity of XKCM1. We next tested the ability of 300 nM tau to inhibit XKCM1 in the same assay. The results show that tau can also inhibit the activity of XKCM1.

Figure 1.

MAPs antagonize the microtubule depolymerizing activity of XKCM1. Plots represent the mean length of microtubules fixed after assembly from tubulin in the presence of the indicated proteins. Error bars show the standard error of the mean. Control, 15 μM tubulin alone; 110 nM XKCM1; 200 nM XMAP215, 300 nM tau.

(b) XMAP215 and tau have a distinct role in regulation of physiological microtubule dynamics

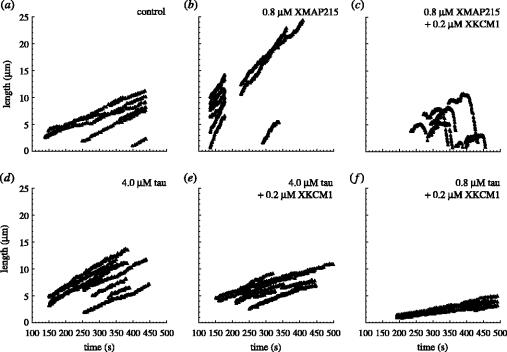

We wanted to see if tau and XMAP215 suppressed the activity of XKCM1 by modulating similar dynamics parameters. Microtubule dynamics can be defined by the growth rate, the shrinkage rate, the catastrophe frequency and the rescue frequency (Walker et al. 1988). To examine the dynamics parameters of microtubules, we observed microtubule dynamics using video enhanced DIC (VE-DIC) microscopy of single microtubules (Walker et al. 1988). Centrosomes were perfused into a chamber, and subsequently, 25 μM tubulin was perfused together with purified proteins or a control buffer and allowed to polymerize. In the presence of 0.2 μM XKCM1 alone, microtubules could not be assembled because the destabilizing activity of XKCM1 was too high (data not shown). Adding XMAP215 (0.8 μM) increased microtubule growth rate to 5.6 μm min−1 (figure 2b), 3–5 times faster than the control (figure 2a), as previously shown. When 0.8 μM XMAP215 was mixed with 0.2 μM XKCM1, microtubules polymerized at about 6 μm min−1, but now had a high catastrophe frequency, as previously shown (figure 2c). This is typical for physiological microtubule dynamics in mitotic cells. To examine the effects of tau, we perfused 4 μM tau together with tubulin. Four μM tau increased the microtubule growth rate slightly to 1.95 μm min−1 (figure 2d). Previous studies found that 1 μM tau markedly increased the rate of assembly (Drechsel et al. 1992), and this apparent difference in the finding with this study may be owing to an effect of the high tau concentration (4 μM). Tau greatly stimulates the rate spontaneous assembly and this can lead to lower than expected growth rates owing to a decrease in the available monomer.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effects of XMAP215 and tau on microtubule dynamics in the presence of XKCM1. Live analysis of microtubule dynamics was done as previously described (Kinoshita et al. 2001). After perfusion of centrosomes and blocking of perfusion chamber surfaces, tubulin and purified proteins or control buffer were perfused into the chamber on ice. The temperature of the perfusion chamber was increased up to 30 °C to allow microtubule polymerization, and the fate of microtubules was monitored by VE-DIC microscopy. Each panel shows life-history traces of microtubules observed with tubulin alone (25 μM) as a control (a), 25 μM tubulin plus 0.8 μM XMAP215 (b), 25 μM tubulin plus 0.8 μM XMAP215 and 0.2 μM XKCM1 (c), 25 μM tubulin plus 4 μM tau (d), 25 μM tubulin plus 4.0 μM tau and 0.2 μM XKCM1 (e) or 25 μM tubulin plus 0.8 μM tau and 0.2 μM XKCM1 (f).

However, when we mixed 4 μM tau and 0.2 μM XKCM1, we observed no catastrophes (figure 2e). Thus tau completely suppressed the catastrophe promoting activity of XKCM1. We lowered the concentration of tau to 0.8 μM but were still unable to see any catastrophes (figure 2f). We therefore conclude that small concentrations of tau that barely stimulate growth rate strongly suppress catastrophe induced by XKCM1.

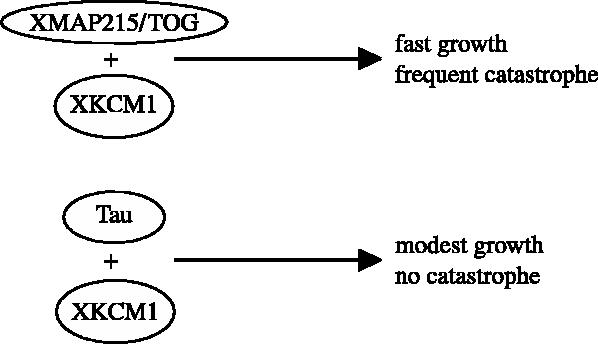

Our results suggest that both XMAP215 and tau can antagonize the microtubule destabilizing activity of XKCM1. The results with the fixed assay suggested that they have equally potent activity in suppressing XKCM1 activity. However, the real-time assay shows they do so by affecting different parameters of microtubule dynamics. Tau mildly stimulates growth rate, but completely blocks catastrophes. XMAP215 stimulates growth rate, but does not block catastrophes completely. Therefore, although the microtubules are of a similar length, those in the presence of XMAP215 are highly dynamic, while those in the presence of tau are non-dynamic. These results are summarized as a model in figure 3.

Figure 3.

A model of how different MAPs counteract XKCM1. The combination of XMAP215 and XKCM1 promotes fast microtubule polymerization with frequent catastrophe, while tau, together with XKCM1, fully abolishes catastrophes while at the same time maintaining a modest polymerization rate.

Both XMAP215 and tau have two activities: to increase the growth rate and to decrease the catastrophe rate. Both of these activities are dependent on the concentration of the protein. Because concentrations of XMAP215 that highly stimulate growth rate do not inhibit XKCM1 completely, the consequences are that the two proteins together can generate high growth rate and high catastrophe rate. However, even small concentrations of tau that have a minor effect on growth rate completely block XKCM1 activity. The consequence of this result is that, using a mixture of tau and XKCM1, it is not possible to generate dynamic microtubules. The only caveat to this conclusion is that tau is a mammalian protein while XKCM1 is a Xenopus protein. These experiments suggest that XMAP215 has evolved to allow highly dynamic microtubules necessary for the process of spindle formation. Tau appears to be much more potent in stabilizing microtubules, thus reducing their dynamic behaviour. Neuronal microtubules are rather stable in comparison to microtubules of proliferating cells (Hirokawa et al. 1996). Therefore, tau seems to have an activity that is perfect for the neuronal environment.

Our results suggest that in different tissues, cells determine the dynamicity and stability of microtubules by expression of specific MAPs according to the dynamic requirements of the microtubule population. Interestingly, even within the XMAP215 family of proteins, proteins have different regulatory properties. For instance, while XMAP215 is a potent inducer of growth rate, Stu2, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue, does not stimulate growth rate (van Breugel et al. 2003). This is presumably an adaptation to the fact that Xenopus eggs are 1000 μm long while yeast cells are only 5 μm in diameter.

We do not know how MAPs inhibit the activity of XKCM1, and therefore can only speculate as to why tau is so much more potent than XMAP215 in inhibiting XKCM1 activity. The classical MAPs tau, MAP2 and MAP4 share a conserved tubulin binding domain with a repeated motif (Lewis et al. 1988; West et al. 1991). In contrast, XMAP215 lacks this conserved domain (Charrasse et al. 1998). Hence, the distinct mode of binding to the microtubule lattice may underlie the difference in counteracting the XKCM1-induced catastrophes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Mark van Breugel and Jeff Stear for help and discussions during the course of this work and for reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

One contribution of 17 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Chromosome segregation’.

References

- Belmont L.D, Hyman A.A, Sawin K.E, Mitchison T.J. Cell. 1990;62:579–589. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrasse S, Schroeder M, Gauthier-Rouviere C, Ango F, Cassimeris L, Gard D.L, Larroque C. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1371–1383. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.10.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Verma S, Mitchison T.J, Walczak C.E. Cell. 1999;96:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel D.N, Hyman A.A, Cobb M.H, Kirschner M.W. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1992;3:1141–1154. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Funakoshi T, Sato-Harada R, Kanai Y. J. Cell Biol. 1996;132:667–679. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.4.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Hyman A.A. Nature. 2003;422:753–758. doi: 10.1038/nature01600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K, Arnal I, Desai A, Drechsel D.N, Hyman A.A. Science. 2001;294:1340–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.1064629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K, Habermann B, Hyman A.A. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S.A, Wang D.H, Cowan N.J. Science. 1988;242:936–939. doi: 10.1126/science.3142041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Nature. 1984a;312:237–242. doi: 10.1038/312237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Nature. 1984b;312:232–237. doi: 10.1038/312232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura H, Garcia M.A, Toda T. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:3805–3812. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.21.3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournebize R, Heald R, Hyman A. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 1997;3:271–284. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5371-7_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Breugel M, Drechsel D, Hyman A. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:359–369. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R.A, O'Brien E.T, Pryer N.K, Soboeiro M.F, Voter W.A, Erickson H.P, Salmon E.D. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:1437–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R.A, Pryer N.K, Salmon E.D. J. Cell Biol. 1991;114:73–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten M.D, Lockwood A.H, Hwo S.Y, Kirschner M.W. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R.R, Tenbarge K.M, Olmsted J.B. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:21 886–21 896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]