Abstract

Calcium release mediated by the ryanodine receptors (RyR) Ca2+ release channels is required for muscle contraction and contributes to neuronal plasticity. In particular, Ca2+ activation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release can amplify and propagate Ca2+ signals initially generated by Ca2+ entry into cells. Redox modulation of RyR function by a variety of non-physiological or endogenous redox molecules has been reported. The effects of RyR redox modification on Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle as well as the activation of signalling cascades and transcription factors in neurons will be reviewed here. Specifically, the different effects of S-nitrosylation or S-glutathionylation of RyR cysteines by endogenous redox-active agents on the properties of skeletal muscle RyRs will be discussed. Results will be presented indicating that these cysteine modifications change the activity of skeletal muscle RyRs, modify their behaviour towards both activators and inhibitors and affect their interactions with FKBP12 and calmodulin. In the hippocampus, sequential activation of ERK1/2 and CREB is a requisite for Ca2+-dependent gene expression associated with long-lasting synaptic plasticity. The effects of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species on RyR channels from neurons and RyR-mediated sequential activation of neuronal ERK1/2 and CREB produced by hydrogen peroxide and other stimuli will be discussed as well.

Keywords: hydrogen peroxide, S-nitrosylation, S-glutathionylation, skeletal muscle, neuronal function, redox regulation

1. Introduction

The cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), which cells at rest maintain at levels less than or equal to 100 nM, can increase rapidly and transiently in response to various types of stimuli (Berridge et al. 2000). Increases in [Ca2+]i can initiate and modulate different cellular events; these include short-term responses, such as muscle contraction and secretion, as well as long-term responses including cell growth and proliferation and the expression of genes required for memory acquisition and learning (Berridge et al. 2003). Furthermore, an uncontrolled increase in [Ca2+]i can lead to an alteration of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis that may trigger apoptosis or cause irreversible cell injury and necrosis.

Two different Ca2+ channels mediate the fast release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, the ryanodine receptors (RyR) and the inositol trisphosphate receptors. Both Ca2+ release channels can increase their activity in response to an increase in [Ca2+]i. This response generates Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), a universal cellular mechanism that allows amplification and propagation of the Ca2+ signals initially created by Ca2+ entry. In particular, ryanodine receptors (RyR)-mediated CICR is required for cardiac muscle contraction and has a central role in secretion and neuronal function, as discussed below.

There are three mammalian RyR isoforms (RyR1, RyR2 and RyR3), which are codified by three different genes localized in three different chromosomes in humans. These proteins were originally identified in skeletal muscle (RyR1), in heart muscle (RyR2) and in brain (RyR3), although it is now known that brain and other tissues express all three mammalian RyR isoforms (Coronado et al. 1994; Furuichi et al. 1994; Mori et al. 2000). Multiple cellular components—including ATP, H+, Ca2+ and Mg2+—and specific proteins, including kinases and phosphatases, as well as endogenous oxidative/nitrosative species, regulate RyR channels (Fill & Copello 2002). In particular, many studies have reported modifications of RyR cysteines by non-physiological redox compounds (for reviews, see Hamilton & Reid 2000; Pessah et al. 2002; Hidalgo et al. 2002). These studies have contributed to the current understanding of how these cysteine modifications change RyR function and affect Ca2+ release; they have also promoted active research into how redox compounds of physiological significance affect RyR activity. These endogenous redox components include the free radicals nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide anion, which through enzymatic or non-enzymatic chemical reactions can be readily converted into non-radical species of lower reactivity but longer half-life such as S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). All these endogenous redox components can modify RyR function (Hidalgo et al. 2004). Additionally, RyR channels are highly susceptible to modification by other endogenous redox agents, including glutathione (GSH), glutathione disulphide (GSSG), NADH, and by changes in the GSH/GSSG ratio (reviewed in Hidalgo et al. 2004).

RyR channels have been proposed to act as intracellular redox sensors (Eu et al. 2000; Hidalgo et al. 2005). The redox sensitivity of skeletal RyR1 is due to the presence of highly reactive cysteine residues in the RyR1 molecule, which have a pK value of 7.4 (Liu et al. 1994; Pessah et al. 2002) and allow RyR1 redox modification at physiological pH. Additionally, RyR1 exhibit a well-defined redox potential (Feng et al. 2000; Xia et al. 2000); through this property they may be susceptible to changes in cellular redox potential. Oxidative/nitrosative modifications that affect RyR function are likely to modify RyR-mediated Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Hence, changes in cellular redox state or generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species (RNS) may result in inhibition or activation of Ca2+ signalling cascades. A review of recent data, showing that redox modifications of the RyR channels present in skeletal muscle cells or neurons exert a central role in regulating single channel properties and CICR from vesicles and cells, will be presented next. A discussion of the effects of redox modifications on the function of cardiac RyR2 channels has been presented elsewhere (Hidalgo et al. 2004).

2. Skeletal muscle

(a) Functional effects of modifications of skeletal muscle RyR1 by ROS/RNS

Physiological activation of RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release in response to muscle depolarization is a very fast process (ms range) which does not require Ca2+ entry into the muscle cells. RyR1 channels open following membrane depolarization, presumably by direct coupling with plasma membrane voltage sensors (Rios & Pizarro 1991). Each of the four homologous 565 kDa RyR1 protein subunits contains approximately 100 cysteine residues (Takeshima et al. 1989). In native RyR1, approximately 50 of these residues appear to be in the reduced state; of these, approximately 10–12 are highly susceptible to oxidation/modification by exogenous sulphydryl (SH) reagents (Sun et al. 2001a). Endogenous redox-active molecules, including molecular oxygen (Eu et al. 2000) and GSSG (Zable et al. 1997; Sun et al. 2001a,b; Aracena et al. 2003), enhance RyR activity. Likewise, H2O2 markedly activates single RyR2 channels (Boraso & Williams 1994) or RyR1 channels maintained under redox control (provided by controlled cytoplasmic and luminal GSH/GSSG ratios; Oba et al. 2002a). Furthermore, superoxide anion generation by a NADH oxidase activity that is present in heavy sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) vesicles and which copurifies with RyR1 channels is presumably responsible for the activation of [3H]-ryanodine binding (a reflection of increased RyR1 activity) produced by 1 mM NADH (Xia et al. 2003).

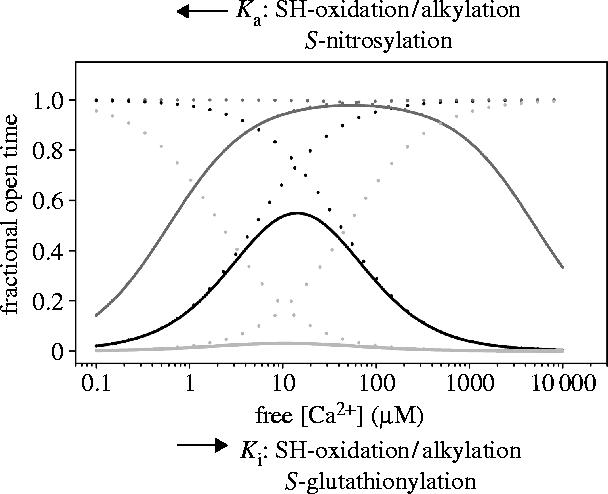

In certain conditions, NO or NO donors enhance RyR1 activity, while in others they exert an inhibitory effect (Stoyanovsky et al. 1997; Suko et al. 1999; Sun et al. 2001a,b, 2003; Eu et al. 2003). In particular, submicromolar NO concentrations activate RyR1 by S-nitrosylation of a single cysteine residue (Cys-3635); this reaction occurs only at low (physiological) pO2 but not at ambient pO2 (Sun et al. 2003). Likewise, in situ generation of NO stimulates whole muscle contractility at low pO2, but inhibits contractility at higher pO2 (Eu et al. 2003). Contrary to NO, GSNO stimulates RyR1 channel activity independently of pO2 through S-nitrosylation of a few critical SH residues other than Cys-3635 (Sun et al. 2003). We have shown that S-nitrosylation of RyR1 enhances its activation by Ca2+, but does not affect the strong inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on CICR (Aracena et al. 2003). Both GSNO and the NO donor NOR-3 produce a significant increase in the S-nitrosylation of RyR1 over the endogenous levels and affect the interactions of RyR1 with FKBP12 and calmodulin, as detailed below. In addition, GSNO or the combination of millimolar GHS plus micromolar H2O2 enhance significantly the endogenous S-glutathionylation of RyR1 (Aracena et al. 2005), a modification that decreases specifically RyR1 inhibition by Mg2+ without affecting its activation by Ca2+ (Aracena et al. 2003). These findings suggest that RyR1 possesses cysteine residues with different susceptibilities to S-glutathionylation or S-nitrosylation, and that these cysteine modifications cause independent effects on RyR1 channel activation by Ca2+ or inhibition by millimolar Mg2+ or Ca2+ (figure 1). The implications of these findings for redox enhancement of CICR in skeletal muscle, as well the possible sources and the activation mechanisms of ROS/RNS generation in living skeletal muscle fibres are discussed in §2b.

Figure 1.

Calcium dependence of the activity of single RyR1 channels. The theoretical curves were obtained as described (Marengo et al. 1998), except that the maximal value of open probability was taken as 1.0 and both the activation and inactivation functions were considered non-cooperative. The solid black curve represents the response to cytoplasmic (cis) [Ca2+] of native RyR channels, which is obtained as the combination of two independent functions (dotted lines), an activation function with Ka=5 μM and an inactivation function with Ki=41 μM. The activation function depicts the channel activation produced by Ca2+ binding to the high-affinity site(s), while the inactivation function describes binding of Ca2+ or Mg2+ to the low-affinity divalent cation inhibitory site(s). Incubation of RyR1 channels with reducing agents increases Ka from 5 to 50 μM and decreases Ki from 41 to 2.2 μM (grey dashed lines), yielding the bell-shaped function represented by the solid light grey line. In contrast, oxidation/alkylation of free sulphydryl residues present in native RyR1 channels decreases Ka from 5 to 0.6 μM and increases Ki from 41 μM to 5 mM (grey dotted lines); these values yield the bell-shaped function represented by the solid dark grey line. RyR1 S-nitrosylation produces only a decrease in Ka, whereas RyR1 S-glutathionylation produces only an increase in Ki.

In mammalian skeletal muscle, RyR1 channels interact with several different accessory proteins, which contribute to tightly regulate their activity. These proteins include the skeletal L-type Ca2+channel dihydropyridine receptor, which acts as voltage sensor during excitation–contraction coupling, triadin, calmodulin, FKBP12 (a 12 kDa FK506 binding protein) and the SR luminal protein calsequestrin (MacKrill 1999; Fill & Copello 2002). Calmodulin in its apocalmodulin (Ca2+-free) form enhances RyR1 channel activity, whereas when present as Ca2+-calmodulin it behaves as a channel inhibitor (Tripathy et al. 1995; Rodney et al. 2000, 2001). At physiological tissue pO2 (approx. 10 mmHg), submicromolar NO activates RyR1 by S-nitrosylation of a single cysteine residue (Cys-3635) (Sun et al. 2003) without affecting Ca2+-calmodulin binding to RyR1 (Eu et al. 2000). The specific S-nitrosylation of Cys-3635, which resides within a calmodulin binding domain, by NO or the NO donor NOC-12 does not take place at ambient pO2; S-nitrosylation of Cys-3635 activates RyR1 and reverses its inhibition by Ca2+-calmodulin (Sun et al. 2003). In contrast, GSNO activates RyR1 by oxidation and S-nitrosylation of thiols other than Cys-3635, and calmodulin is not involved (Sun et al. 2003). In triad vesicles isolated from skeletal muscle, we have found that S-nitrosylation or S-glutathionylation of triad proteins, including RyR1, increase the Kd of [35S]-Ca2+-calmodulin and of [35S]-apocalmodulin binding to triads without affecting maximal binding capacity (Bmax). Moreover, the combined S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation induced by GSNO increases by fourfold the Kd of [35S]-Ca2+-calmodulin binding to triads and abolishes the binding of [35S]-apocalmodulin (Aracena et al. 2005).

FKBP12 is another RyR1 regulatory protein that may specifically coordinate RyR1 channel gating (Gaburjakova et al. 2001). Removal of this protein with rapamycin or FK506 leads to RyR1 activation and promotes the emergence of sub-conductance states in single RyR1 channels incorporated in lipid bilayers (Ma et al. 1995; Kaftan et al. 1996). In addition, tissue-specific FKBP12 knockout mice exhibit altered orthograde and retrograde signalling between the voltage sensor and RyR1, leading to altered L-type currents (Tang et al. 2004). We have found that [35S]-FKBP12 binds to RyR1 present in triads or heavy SR vesicles with similar affinity (Kd=13.1 nM) (Aracena et al. in press). These results indicate that RyR1–voltage sensor interactions do not affect the high-affinity binding of FKBP12 to RyR1. RyR1 S-nitrosylation, but not S-glutathionylation, specifically increases fivefold the Kd value of FKBP12 binding to RyR1 without affecting Bmax (Aracena et al. 2005).

Since both FKBP12 and Ca2+-calmodulin inhibit RyR1 activity, decreased binding of these proteins to RyR1 may contribute to the activation of CICR release kinetics induced by S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation (Aracena et al. 2003). Furthermore, in vivo conditions that promote the combined S-nitrosylation and S-glutathionylation of RyR1 are bound to alter both FKBP12 and calmodulin binding to RyR1, and thus may alter excitation–contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibres.

(b) Relevance of RyR1 modifications induced by ROS/RNS to skeletal muscle function

The results discussed so far indicate that channel S-nitrosylation enhances Ca2+ release by increasing the affinity of Ca2+ binding to RyR1 (Aracena et al. 2003). Mammalian skeletal muscle contains endogenous sources of NO, and it has been reported that endogenous NO generated by nNOS induces a significant enhancement of whole-muscle contractility at low (physiological) pO2 but not at ambient pO2 (Eu et al. 2003). Moreover, cysteine RyR1 modifications that enhance channel activation by Ca2+ and ATP (Marengo et al. 1998; Oba et al. 2002b; Aracena et al. 2003; Bull et al. 2003), and especially those that reduce the powerful inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release (Donoso et al. 2000; Aracena et al. 2003) may stimulate CICR in living skeletal muscle fibres. In vitro, submillimolar [Mg2+] strongly inhibits RyR1 channels (Laver et al. 1997) and RyR1-mediated Ca2+ release (Meissner et al. 1986; Moutin & Dupont 1988; Donoso et al. 2000; Aracena et al. 2003). Mg2+ inhibition may be a contributing factor to the reported lack of sparks due to spontaneous CICR in skeletal muscle fibres (Shirokova et al. 1998).

(c) RyR1 S-glutathionylation

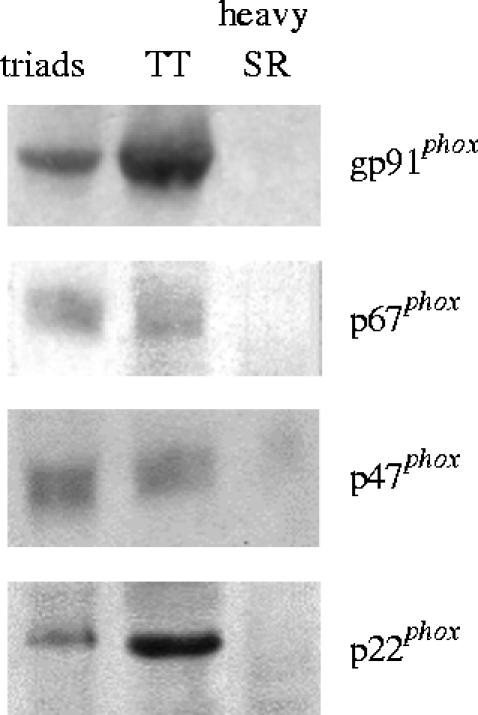

Endogenous generation of ROS or GSNO (via NO generation) may enhance RyR S-glutathionylation, and thus may overcome the strong inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on CICR. Skeletal muscle fibres generate ROS following physiological contraction (Bejma & Li 1999; Reid & Durham 2002) as well as during heat stress conditions (Stofan et al. 2000). Skeletal muscle homogenates contain a constitutively active non-phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase complex that generates superoxide anion (Javesghani et al. 2002). Enzymatic or spontaneous dismutation of superoxide anion generates hydrogen peroxide, which markedly activates RyR1 in vitro (Favero et al. 1995; Oba et al. 2002a) but does not seem to play a significant role in the post fatigue recovery process (Oba et al. 2002a). We have found the membrane bound components of NAD(P)H oxidase (gp91phox and p22phox) in skeletal muscle transverse tubules, which are absent from heavy SR vesicles (figure 2). Activation of this transverse tubular NAD(P)H oxidase, which generates superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide, leads to S-glutathionylation and stimulation of the neighbouring RyR1 in isolated triad vesicles (Hidalgo et al. in preparation). It has been reported that exogenously added hydrogen peroxide stimulates caffeine-induced contractions in skinned skeletal muscle fibres; in contrast, addition of hydrogen peroxide does not affect action potential-generated contractions (Posterino et al. 2003). These results support activation by hydrogen peroxide of RyR1-mediated CICR but not of depolarization-induced Ca2+ release. Furthermore, in skinned skeletal muscle fibres hydrogen peroxide activates contraction without producing an increase in [Ca2+]i (Andrade et al. 1998) or even after causing [Ca2+]i to decrease (Andrade et al. 2001). Hence, a definite demonstration of the relevance of RyR1 modifications by hydrogen peroxide in the context of physiological gating of the channel during excitation–contraction coupling is still missing (Lamb & Posterino 2003). It is not known, however, if reducing or oxidizing agents externally added to skeletal muscle cells effectively cause RyR1 redox modifications. This issue is important since RyR1 present endogenous levels of S-glutathionylation when isolated (Aracena et al. 2005), an indication that RyR1s effectively function in vivo with some S-glutathionylated cysteine residues. Although the cellular sources of this RyR1 redox modification are not established, the transverse tubule NAD(P)H oxidase may contribute to this modification. This enzyme may provide direct redox control of RyR1 function, so that increased muscle activity may result in enhanced RyR1 S-glutathionylation and Ca2+ release. We have preliminary data indicating that depolarization of muscle cells in culture activates this transverse tubule NAD(P)H oxidase, which in turn stimulates RyR1 activity (Espinosa et al. in preparation; P. Aracena, C. Gilman, S. L. Hamilton & C. Hidalgo, unpublished observations). It remains to be investigated, however, whether RyR1 S-glutathionylation increases following physiological activation of skeletal muscle fibres, and whether this specific RyR1 redox modification affects the physiological excitation–contraction coupling process.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis to test the presence of NAD(P)H subunits in triads, transverse tubules (TT) and junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (heavy SR) vesicles devoid of transverse tubules. Isolated triad vesicles contain 10–15% TT still attached to junctional SR membranes. All membrane fractions were isolated from mammalian skeletal muscle as described (Barrientos & Hidalgo 2002). Mouse monoclonal anti-gp91phox, anti-p22phox, anti-p47phox and anti-p67phox antibodies were a kind gift from Dr Mark T. Quinn (Veterinary Molecular Biology, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT).

(d) RyR1 S-nitrosylation

There is experimental evidence indicating that NO-induced RyR1 cysteine S-nitrosylation affects muscle function. RyR1 channel S-nitrosylation caused by endogenous NO generation is likely responsible for the reported increase in skeletal muscle contractility observed at physiological pO2 (Eu et al. 2003). In single skeletal muscle fibres from mouse, challenged by short membrane depolarizations under voltage-clamp conditions, NO donors induce a progressive increase in resting [Ca2+]i (Pouvreau et al. 2004). High NO levels may produce continuous Ca2+ leak from the SR, possibly mediated by redox-modified RyR1s that do not close once they are activated by membrane depolarization. This SR Ca2+ leak and the resulting increase in resting [Ca2+]i may be important in mediating the effects of excess NO on voltage-activated Ca2+ release.

3. Neurons

Several neuronal functions, including synaptic plasticity and gene expression, require transient elevation of [Ca2+]i (Berridge 1998; Berridge et al. 2000). This increase is initially produced by Ca2+ influx through plasma membrane voltage- or receptor-activated Ca2+ channels following neuronal stimulation. In addition, Ca2+ entry can stimulate Ca2+ release from intracellular stores via CICR or depolarization-induced Ca2+ release. A variety of experimental findings indicate that Ca2+ release from stores elicits diverse neuronal responses (Simpson et al. 1995; Chameau et al. 2001; Meldolesi 2001; Verkhratsky & Petersen 2002; Bouchard et al. 2003; Ouardouz et al. 2003; Pape et al. 2004; Gafni et al. 2004). Through CICR neurons can amplify and propagate the initial Ca2+ entry signal, leading to activation of most calcium-regulated transcription factors (Berridge 1998). In particular, RyR-mediated Ca2+ release may have a role in synaptic plasticity and gene expression in neurons (Berridge 1998; Futatsugi et al. 1999; Berridge et al. 2000; Carafoli 2002; Carrasco et al. 2004; Verkhartsky 2004). RyR-mediated Ca2+ release may also be involved in causing neurodegenerative processes, as discussed below.

Of the three RyR isoforms expressed in different brain regions, RyR2 is the most abundant (Furuichi et al. 1994; Giannini et al. 1995; Mori et al. 2000). Despite the emerging importance of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release for brain function, there is limited information on how these different RyR isoforms contribute to the generation and/or regulation of the Ca2+ signals that underlie diverse Ca2+ dependent neuronal functions. It is known, however, that membrane depolarization activates RyRs in several neuronal types (Chavis et al. 1996; Mouton et al. 2001; De Crescenzo et al. 2004), Yet, the properties and regulation of RyR channels from brain have been less studied than those of their skeletal or cardiac counterparts.

(a) Redox modulation of brain RyR

CICR relies on the fact that RyR are activated by an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration, from the submicromolar to the micromolar range; in cells this activation occurs in the presence of ATP and Mg2+. We have studied at the single-channel level the activation induced by Ca2+ and ATP of native and oxidized RyR channels from rat brain endoplasmic reticulum. Native RyR channels from rat brain cortex incorporated in planar lipid bilayers display three different Ca2+ dependencies (Marengo et al. 1996), which can be interchanged through modifications of RyR redox state (Marengo et al. 1998; Hidalgo et al. 2004). In brief, highly reduced channels (a condition in which most RyR1 cysteine residues have free SH groups) respond poorly to Ca2+ activation, whereas increasing cysteine oxidation/alkylation increases the channel response to micromolar [Ca2+] and decreases the inhibitory effect of higher [Ca2+]. Noteworthy, reducing agents reverse all these changes whereas ATP differentially activates RyR channels depending on their Ca2+ response, so that more oxidized channels from brain require less ATP to attain maximal activation (Bull et al. 2003). We have found that modification of brain RyR cysteine residues with thimerosal decreases the inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on RyR activity whereas reducing agents have the opposite effect (R. Bull et al. in preparation). Changes in the redox state of RyR channels from brain affect as well RyR modulation by glucosylceramide (Lloyd-Evans et al. 2003), a type of glycosphingolipid that may be implicated in the cell death observed in Alzheimer's disease (Cutler et al. 2004) and HIV dementia (Haughey et al. 2004). Interestingly, the finding that glucosylceramide augments agonist-stimulated Ca2+ release via RyR channels (Lloyd-Evans et al. 2003) may be relevant to understand the development of pathological conditions that entail a faulty regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in pathological conditions.

(b) Participation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release in long-term potentiation induction and CREB activation in the hippocampus

Activation of the nuclear transcription factor CREB (cAMP/calcium response element binding protein) is crucial for several neuronal functions, including activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (Silva et al. 1998; Lonze & Ginty 2002). Activation of CREB and the ensuing CRE-mediated transcription are required for induction of long-term potentiation (LTP), a reversible increase in synaptic transmission inducible in several brain regions in response to tetanic stimulation of afferent fibres. LTP is considered a cellular model of synaptic plasticity that may underlie higher brain functions such as learning and memory (Lynch 2004). A number of genes activated by neuronal electrical activity, among them c-fos and BDNF, have functional CRE sequences in their promoters (Sheng et al. 1990; Tao et al. 1998); in the last few years these findings have prompted many studies on the cellular factors that regulate CREB activation.

Participation of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in LTP induction has been described (Auerbach & Segal 1994; Wang et al. 1996; Reyes-Harde et al. 1999; Lu & Hawkins 2002; Lauri et al. 2003; Matias et al. 2003; Lynch 2004). LTP induction in most hippocampal synapses requires a rise in intracellular postsynaptic [Ca2+] mediated by N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, with contributions from L-type channel activation and intracellular Ca2+ stores (Matias et al. 2003; Lynch 2004). In the CA1 hippocampal region, RyR blockade significantly reduces tetanic-, NO- and cGMP-induced LTP, and decreases P-CREB immunofluorescence in postsynaptic neurons of hippocampal slices (Lu & Hawkins 2002). These results point to a well-defined postsynaptic location of the RyR channels involved in hippocampal LTP induction. A presynaptic effect of NO resulting in induction of long-term depression (LTD) as well as LTP in the same hippocampal region has also been described (Reyes-Harde et al. 1999). A contribution of RyR, in this case presynaptic, has been suggested by the marked reduction of LTD produced by ryanodine when used at inhibitory concentrations. Interestingly, a switch from LTD to LTP was induced at the hippocampal dentate gyrus by a low stimulatory ryanodine concentration, suggesting that RyR-mediated Ca2+ release plays a significant role in LTP induction (Wang et al. 1996).

Presynaptic RyR also contribute to LTP generation in mossy hippocampal fibres (Lauri et al. 2003). This form of LTP is independent of NMDA receptors; instead, Ca2+ entry is mediated by presynaptic kainate glutamate receptors, which initiate a calcium-signalling cascade involving RyR-mediated Ca2+ release that is abolished by inhibitory ryanodine concentrations. In addition, caffeine (10 mM) can evoke LTP in CA1 hippocampal neurons, which is different to the classical LTP since it does not require postsynaptic receptor activation or Ca2+ increase in this area (Martin & Buño 2003). This new form of LTP is generated presynaptically, through the interaction of caffeine with presynaptic purinergic receptors and RyR channels. The resulting increased Ca2+ signals enhance neurotransmitter release.

In the hippocampus, Ca2+-dependent activation of the Ras/ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) pathway is essential for long-term CREB phosphorylation and CREB-dependent transcription of genes involved in synaptic plasticity (Hardingham & Bading 1999; Impey & Goodman 2001; Thiels & Klann 2001; Wu et al. 2001; Adams & Sweatt 2002; Dolmetsch 2003; Lynch 2004). Furthermore, functionally active neurons display increased metabolic activity plus increased oxygen consumption and generation of ROS/RNS (Davis et al. 1998; Yermolaieva et al. 2000). Several studies indicate that ROS/RNS may regulate synaptic plasticity. Activity-dependent nitric oxide generation has been associated with synaptic plasticity and Ca2+ signalling (Peunova & Enikolopov 1993; Yermolaieva et al. 2000), including Ca2+-dependent activation of CREB-phosphorylation in the hippocampus (Lu & Hawkins 2002). Activation of NMDA receptors generates superoxide anion in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons in culture and in brain hippocampal slices (Bindokas et al. 1996), while cell-permeable scavengers of superoxide anion block LTP induction in area CA1 of the hippocampus (Klann 1998). Noteworthy, transgenic mice that overexpress extracellular superoxide dismutase (a superoxide anion scavenger) exhibit impaired LTP in hippocampal area CA1, despite normal LTP in area CA3, and also show defects in memory acquisition (Thiels et al. 2000). These findings strongly suggest that superoxide anion (or its derivative, hydrogen peroxide) is a required signalling molecule for LTP induction and normal neuronal function. Yet, dissimilar results on the effects of hydrogen peroxide on hippocampal LTP induction have been reported (Kamsler & Segal 2004). Initial augmentation, and subsequent long-lasting depression, of population spikes and excitatory postsynaptic potentials by hydrogen peroxide (0.3–2.9 mM) has been described in the CA1 region of rat hippocampal slices (Katsuki et al. 1997). In contrast, low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (1 μM) cause a twofold increase in tetanic LTP and enhance NMDA-independent LTP in the hippocampus compared to controls (Kamsler & Segal 2003).

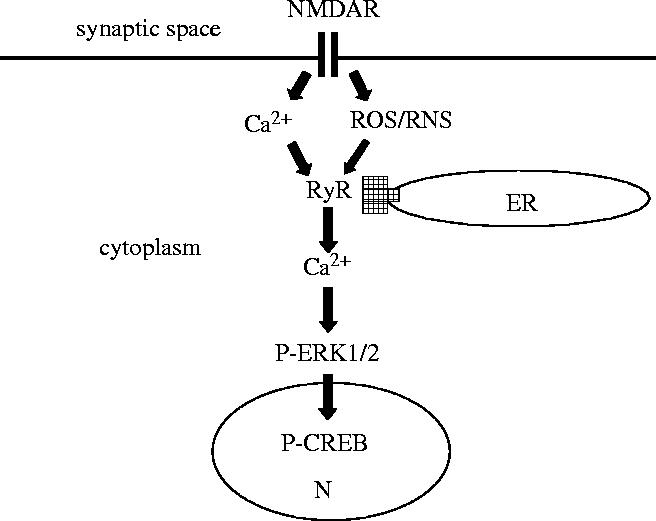

The preceding discussion of the literature indicates that LTP induction in hippocampal neurons entails a combined increase of [Ca2+]i, ROS and RNS. All these factors can potentially contribute to enhance RyR-mediated Ca2+ release; the resulting amplified Ca2+ signals may in turn enhance the long-lasting Ca2+-dependent ERK/CREB phosphorylation cascade required for LTP induction. Hence, it is of interest to investigate whether ROS/RNS stimulate the Ca2+-dependent Ras/ERK pathway through stimulation of RyR-mediated CICR. To this aim, we have studied the effects of hydrogen peroxide and membrane depolarization on ERK/CREB phosphorylation in neurons with functional or inhibited RyR. We exposed N2a and hippocampal cells in primary culture cells to hydrogen peroxide (Carrasco et al. 2004; Kemmerling et al. submitted). In both cell types, exogenous hydrogen peroxide activates CREB and ERKs and promotes RyR-dependent Ca2+ release; these effects are independent of extracellular Ca2+ and are inhibited significantly by ryanodine concentrations that block RyR-mediated Ca2+ release. Furthermore, thapsigargin antagonizes the increase in P-CREB levels induced by hydrogen peroxide, which also promotes RyR s-glutathionylation (Kemmerling et al. submitted). These results suggest that oxidative stimulation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release is an intermediate step in the activation of the ERK/CREB phosphorylation cascade required for synaptic plasticity (figure 3). We also found that depolarization induced by high K+ concentration stimulates CREB phosphorylation in the neuroblastoma cell line N2a (Carrasco et al. 2004). Inhibitory concentrations of ryanodine partially reduced depolarization-induced CREB phosphorylation, suggesting that RyR-mediated Ca2+ release contributes to the observed stimulation.

Figure 3.

Proposed model to illustrate the potential role of neuronal RyR as coincidence detectors of a simultaneous increase in [Ca2+] and ROS/RNS. As discussed in the text, stimulation of postsynaptic NMDA receptors (NMDAR) in hippocampal neurons elicits Ca2+ entry and promotes ROS generation; the resulting localized [Ca2+] increase stimulates the Ca2+-dependent neuronal NO synthase that is attached to the postsynaptic membrane, resulting in the generation of NO and possibly of other NO-derived RNS. The model proposes that the concomitant local increases in Ca2+ and ROS/RNS activate jointly RyR-mediated Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), generating larger Ca2+ signals. The resulting RyR-mediated Ca2+ signals would stimulate Ca2+-dependent signalling cascades, such as the Ras MAP kinase pathway, producing increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Translocation of phospho-ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2) to the nucleus (N) would stimulate the sustained phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB, which is a requisite for transcription of genes involved in synaptic plasticity. According to this model, cross talk between Ca2+ and redox signals through joint stimulation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release may play a key role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Furthermore, conditions that promote oxidative/nitrosative stress may result in excessive stimulation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release that if unchecked can provoke pathological responses and neuronal death.

4. Conclusions

Through either depolarization-induced Ca2+ release or via CICR, RyR channels have a pivotal role in the generation or amplification of Ca2+ signals that are required for muscle contraction and neuronal plasticity. Endogenous activation of RyR channels by cellular ROS/RNS may represent a physiological mechanism of cross talk between Ca2+ and redox signalling pathways. Thus, cells may use redox-modulated RyR-mediated Ca2+ release as an additional mechanism to either amplify or inhibit Ca2+ signals as needed for a specific response. In neurons, generation of ROS/RNS such as hydrogen peroxide or NO, which may act as diffusible signal molecules in synaptic plasticity, may modify cellular processes that depend on RyR-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER, including LTP and LTD, and presumably learning and memory. Oxidative stress and alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis may contribute to neuronal apoptosis and excitotoxicity, which may underlie the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative disorders (Mattson 2000; Mattson & Chan 2003). In particular, RyR channels may be involved in the pathophysiology of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease (Kelliher et al. 1999; Chan et al. 2000; Mungarro-Menchaca et al. 2002). As discussed here, oxidative stress is likely to enhance RyR-mediated CICR in neurons. Thus, redox modification of RyR channels may have physiological and pathological consequences for neuronal function.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the insightful comments of P. Donoso and M. A. Carrasco on the manuscript, and R. Bull for providing figure 1. This work was supported by the FONDAP Center for Molecular Studies of the Cell, Fondo Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (FONDECYT) project 15010006.

Footnotes

One contribution of 18 to a Theme Issue ‘Reactive oxygen species in health and disease’.

References

- Adams J.P, Sweatt J.D. Molecular psychology: roles for the ERK MAP kinase cascade in memory. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:135–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082701.145401. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082701.145401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade F.H, Reid M.B, Allen D.G, Westerblad H. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J. Physiol. 1998;509:565–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.565bn.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.565bn.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade F.H, Reid M.B, Westerblad H. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. FASEB J. 2001;15:309–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.565bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aracena P, Sánchez G, Donoso P, Hamilton S.L, Hidalgo C. S-glutathionylation decreases Mg2+ inhibition and S-nitrosylation enhances Ca2+ activation of RyR1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42 927–42 935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306969200. 10.1074/jbc.M306969200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aracena P, Tang W, Hamilton S.L, Hidalgo C. Effects of S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation on calmodulin binding to triads and FKBP-12 binding to type 1 calcium release channels. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005;7:870–881. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach J.M, Segal M. A novel cholinergic induction of long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2034–2040. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos G, Hidalgo C. Annexin VI is attached to transverse-tubular membranes in isolated skeletal muscle triads. J. Membr. Biol. 2002;188:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0179-x. 10.1007/s00232-001-0179-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejma J, Ji L.L. Aging and acute exercise enhance free radical generation in rat skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;87:465–470. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.1.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J. Neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron. 1998;21:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80510-3. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80510-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J, Lipp P, Bootman M.D. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. 10.1038/35036035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J, Bootman M.D, Roderick H.L. Calcium signaling; dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. 10.1038/nrm1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindokas V.P, Jordan J, Lee C.C, Miller R.J. Superoxide production in rat hippocampal neurons: selective imaging with hydroethidine. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1324–1336. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01324.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraso A, Williams A.J. Modification of the gating of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel by H2O2 and dithiothreitol. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:H1010–H1016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard R, Pattarini R, Geiger J.D. Presence and functional significance of presynaptic ryanodine receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 2003;69:391–418. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00053-4. 10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull, R. Finkelstein, J. P., Humeres, A., Behrens, M. I. & Hidalgo, C. In Preparation. Modulation by ATP and Mg2+ of the calcium dependence of RyR-channels from rat brain. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bull R, Marengo J.J, Finkelstein J.P, Behrens M.I, Alvarez O. SH oxidation coordinates subunits of rat brain ryanodine receptor channels activated by calcium and ATP. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C119–C128. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00296.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E. Calcium signaling: a tale for all seasons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1115–1122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032427999. 10.1073/pnas.032427999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco M.A, Jaimovich E, Kemmerling U, Hidalgo C. Signal transduction and gene expression regulated by calcium release from internal stores in excitable cells. Biol. Res. 2004;37:701–712. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000400028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chameau U.P, Van D.V, Fossier P, Baux G. Ryanodine-, IP3- and NAADP-dependent calcium stores control acetylcholine release. Pflugers Arch. 2001;443:289–296. doi: 10.1007/s004240100691. 10.1007/s004240100691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S.L, Mayne M, Holden C.P, Geiger J.D, Mattson M.P. Presenilin-1 mutations increase levels of ryanodine receptors and calcium release in PC12 cells and cortical neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:18 195–18 200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000040200. 10.1074/jbc.M000040200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis P, Fagni L, Lansman J.B, Bockaert J. Functional coupling between ryanodine receptors and L-type calcium channels in neurons. Nature. 1996;382:719–722. doi: 10.1038/382719a0. 10.1038/382719a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronado R, Morrissette J, Sukhareva M, Vaughan D.M. Structure and function of ryanodine receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:C1485–C1504. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler R.G, Kelly J, Storie K, Pedersen W.A, Tammara A, Hatanpaa K, Troncoso J.C, Mattson M.P. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305799101. 10.1073/pnas.0305799101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T.L, Kwong K, Weisskoff R.M, Rosen B.R. Calibrated functional MRI: mapping the dynamics of oxidative metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1834–1839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1834. 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Crescenzo V, et al. Ca2+ syntillas, miniature Ca2+ release events in terminals of hypothalamic neurons, are increased in frequency by depolarization in the absence of Ca2+ influx. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:1226–1235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4286-03.2004. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4286-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch R. Excitation–transcription coupling: signaling by ion channels to the nucleus. Sci. STKE. 2003;Jan 21:PE 4. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.166.pe4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoso P, Aracena P, Hidalgo C. Sulfhydryl oxidation overrides Mg2+ inhibition of calcium-induced calcium release in skeletal muscle triads. Biophys. J. 2000;79:279–286. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, A., Leiva, A., Peña, M., Müller, M., Debandi, A., Hidalgo, C., Carrasco, M. A. & Jaimovich, E. In preparation. Myotube depolarization generates reactive oxygen species through NAD (P) H oxidase; ROS-elicited Ca2+ stimulates ERK, CREB and early genes. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eu J.P, Sun J, Xu L, Stamler J.S, Meissner G. The skeletal muscle calcium release channel: coupled O2 sensor and NO signaling functions. Cell. 2000;102:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00054-4. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00054-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eu J.P, et al. Concerted regulation of skeletal muscle contractility by oxygen tension and endogenous nitric oxide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15 229–15 234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433468100. 10.1073/pnas.2433468100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favero T.G, Zable A.C, Abramson J.J. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates the Ca2+ release channel from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:25 557–25 563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25557. 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W, Liu G, Allen P.D, Pessah I.N. Transmembrane redox sensor of ryanodine receptor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35 902–35 907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000523200. 10.1074/jbc.C000523200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fill M, Copello J.A. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi T, Furutama D, Hakamata Y, Nakai J, Takeshima H, Mikoshiba K. Multiple types of ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels are differentially expressed in rabbit brain. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:4794–4805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04794.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futatsugi A, Kato K, Ogura H, Li S.T, Nagata E, Kuwajima G, Tanaka K, Itohara S, Mikoshiba K. Facilitation of NMDAR-independent LTP and spatial learning in mutant mice lacking ryanodine receptor type 3. Neuron. 1999;24:701–713. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81123-x. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81123-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaburjakova M, Gaburjakova J, Reiken S, Huang F, Marx S.O, Rosemblit N, Marks A.R. FKBP12 binding modulates ryanodine receptor channel gating. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:16 931–16 935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100856200. 10.1074/jbc.M100856200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafni J, Wong P.W, Pessah I.N. Non-coplanar 2,2′,3,5′,6-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 95) amplifies ionotropic glutamate receptor signaling in embryonic cerebellar granule neurons by a mechanism involving ryanodine receptors. Toxicol. Sci. 2004;77:72–82. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh004. 10.1093/toxsci/kfh004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini G, Conti A, Mammarella S, Scrobogna M, Sorrentino V. The ryanodine receptor/calcium channel genes are widely and differentially expressed in murine brain and peripheral tissues. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:893–904. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.893. 10.1083/jcb.128.5.893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton S.L, Reid M.B. RyR1 modulation by oxidation and calmodulin. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2000;2:41–45. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham G.E, Bading H. Control of recruitment and transcription-activating function of CBP determines gene regulation by NMDA receptors and L-type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999;22:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80737-0. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80737-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey N.J, Cutler R.G, Tamara A, MCarthur J.C, Vargas D.L, Pardo C.A, Turchan J, Nath A, Mattson M.P. Perturbation of sphingolipid metabolism and ceramide production in HIV-dementia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:257–267. doi: 10.1002/ana.10828. 10.1002/ana.10828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo C, Aracena P, Sánchez G, Donoso P. Redox regulation of calcium release in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biol. Res. 2002;35:183–193. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602002000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo C, Bull R, Carrasco M.A, Donoso P. Redox regulation of RyR-mediated Ca2+ release in muscle and neurons. Biol. Res. 2004;37:539–552. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo C, Donoso P, Carrasco M.A. The ryanodine receptors Ca2+ release channels: cellular redox sensors? IUBMB Life. 2005;57:315–322. doi: 10.1080/15216540500092328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, C., Sánchez, G. & Aracena, P. In preparation. A transverse tubule NOX activity stimulates calcium release via RyR1 redox modification.

- Impey S, Goodman R. CREB signaling-timing is everything. Sci. STKE. 2001;May 15:PE 1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.82.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javesghani D, Magder S.A, Barreiro E, Quinn M.T, Hussain S.N. Molecular characterization of a superoxide-generating NAD(P)H oxidase in the ventilatory muscles. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;165:412–418. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.3.2103028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaftan E, Marks A.R, Ehrlich B.E. Effects of rapamycin on ryanodine receptor/Ca2+-release channels from cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 1996;78:990–997. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.6.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamsler A, Segal M. Paradoxical actions of hydrogen peroxide on long-term potentiation in transgenic superoxide dismutase-1 mice. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:269–276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10359.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamsler A, Segal M. Hydrogen peroxide as a diffusible signal molecule in synaptic plasticity. Mol. Neurobiol. 2004;29:167–178. doi: 10.1385/MN:29:2:167. 10.1385/MN:29:2:167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki H, Nakanishi C, Saito H, Matsuki N. Biphasic effect of hydrogen peroxide on field potentials in rat hippocampal slices. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;337:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01323-x. 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01323-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher M, Fastbom J, Cowburn R.F, Bonkale W, Ohm T.G, Ravid R, Sorrentino V, O'Neill C. Alterations in the ryanodine receptor calcium release channel correlate with Alzheimer's disease neurofibrillary and beta-amyloid pathologies. Neuroscience. 1999;92:499–513. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00042-1. 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00042-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerling, U., Muñoz, P., Müller, M., Sánchez, G., Aylwin, M. L., Klann, E., Carrasco, M. A. & Hidalgo, C. Submitted. Ryanodine receptors mediate the activation of ERK and CREB phosphorylation induced by hydrogen peroxide in N2a cells and hippocampal neurons. J. Biol Chem. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Klann E. Cell-permeable scavengers of superoxide prevent long-term potentiation in hippocampal area CA1. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:452–457. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb G.D, Posterino G.S. Effects of oxidation and reduction on contractile function in skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J. Physiol. 2003;546:149–163. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.027896. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.027896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauri S.E, Bortolotto Z.A, Nistico R, Bleakman D, Ornstein P.L, Lodge D, Isaac J.T, Collingridge G.L. A role for Ca2+ stores in kainate receptor-dependent synaptic facilitation and LTP at mossy fiber synapses in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2003;39:327–341. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00369-6. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00369-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver D.R, Baynes T.M, Dulhunty A.F. Magnesium inhibition of ryanodine-receptor calcium channels: evidence for two independent mechanisms. J. Membr. Biol. 1997;156:213–229. doi: 10.1007/s002329900202. 10.1007/s002329900202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Abramson J.J, Zable A.C, Pessah I.N. Direct evidence for the existence and functional role of hyperreactive sulfhydryls on the ryanodine receptor-triadin complex selectively labeled by the coumarin maleimide 7-diethylamino-3-(4′-maleimidylphenyl)-4-methylcoumarin. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:189–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Evans E, Pelled D, Riebeling C, Bodennec J, De Morgan A, Waller H, Schiffmann R, Futerman A.H. Glucosylceramide and glucosylsphingosine modulate calcium mobilization from brain microsomes via different mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:23 594–23 599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300212200. 10.1074/jbc.M300212200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze B.E, Ginty D.D. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00828-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.F, Hawkins R.D. Ryanodine receptors contribute to cGMP-induced late-phase LTP and CREB phosphorylation in the hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1270–1278. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M.A. Long-term potentiation and memory. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:87–136. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2003. 10.1152/physrev.00014.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Bhat M.B, Zhao J. Rectification of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor mediated by FK506 binding protein. Biophys. J. 1995;69:2398–2404. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80109-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKrill J.J. Protein–protein interactions in intracellular Ca2+-release channel function. Biochem. J. 1999;337:345–361. 10.1042/0264-6021:3370345 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo J.J, Bull R, Hidalgo C. Calcium dependence of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels from brain cortex endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 1996;383:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00222-0. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00222-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo J.J, Hidalgo C, Bull R. Sulfhydryl oxidation modifies the calcium dependence of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels of excitable cells. Biophys. J. 1998;74:1263–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77840-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín E.D, Buño W. Caffeine-mediated presynaptic long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;89:3029–3038. doi: 10.1152/jn.00601.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias C.M, Dionisio J.C, Arif M, Quinta-Ferreira M.E. Effect of D-2 amino-5-phosphonopentanoate and nifedipine on postsynaptic calcium changes associated with long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 area. Brain Res. 2003;976:90–99. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02698-2. 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02698-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P. Apoptosis in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:120–129. doi: 10.1038/35040009. 10.1038/35040009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P, Chan S.L. Neuronal and glial calcium signaling in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00128-3. 10.1016/S0143-4160(03)00128-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G, Darling E, Eveleth J. Kinetics of rapid Ca2+ release by sarcoplasmic reticulum. Effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, and adenine nucleotides. Biochemistry. 1986;25:236–244. doi: 10.1021/bi00349a033. 10.1021/bi00349a033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldolesi J. Rapidly exchanging Ca2+ stores in neurons: molecular, structural and functional properties. Prog. Neurobiol. 2001;65:309–338. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00004-1. 10.1016/S0301-0082(01)00004-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori F, Fukaya M, Abe H, Wakabayashi K, Watanabe M. Developmental changes in expression of the three ryanodine receptor mRNAs in the mouse brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;285:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01046-6. 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01046-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutin M.J, Dupont Y. Rapid filtration studies of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum. Role of monovalent ions. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:4228–4235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton J, Marty I, Villaz M, Feltz A, Maulet Y. Molecular interaction of dihydropyridine receptors with type-1 ryanodine receptors in rat brain. Biochem. J. 2001;354:597–603. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540597. 10.1042/0264-6021:3540597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungarro-Menchaca X, Ferrera P, Moran J, Arias C. beta-Amyloid peptide induces ultrastructural changes in synaptosomes and potentiates mitochondrial dysfunction in the presence of ryanodine. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;68:89–96. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10193. 10.1002/jnr.10193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba T, Kurono C, Nakajima R, Takaishi T, Ishida K, Fuller G.A, Klomkleaw W, Yamaguchi M. H2O2 activates ryanodine receptor but has little effect on recovery of releasable Ca2+ content after fatigue. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002a;93:1999–2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00097.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba T, Murayama T, Ogawa Y. Redox states of type 1 ryanodine receptor alter Ca(2+) release channel response to modulators. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002b;282:C684–C692. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.01273.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouardouz M, et al. Depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in ischemic spinal cord white matter involves L-type Ca2+ channel activation of ryanodine receptors. Neuron. 2003;40:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.016. 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape H.C, Munsch T, Budde T. Novel vistas of calcium-mediated signalling in the thalamus. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1234-5. 10.1007/s00424-003-1234-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah I.N, Kim K.H, Feng W. Redox sensing properties of the ryanodine receptor complex. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:a72–a79. doi: 10.2741/A741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peunova N, Enikolopov G. Amplification of calcium-induced gene transcription by nitric oxide in neuronal cells. Nature. 1993;364:450–453. doi: 10.1038/364450a0. 10.1038/364450a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posterino G.S, Cellini M.A, Lamb G.D. Effects of oxidation and cytosolic redox conditions on excitation–contraction coupling in rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2003;547:807–823. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035204. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouvreau S, Allard B, Berthier C, Jacquemond V. Control of intracellular calcium in the presence of nitric oxide donors in isolated skeletal muscle fibres from mouse. J. Physiol. 2004;560:779–794. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072397. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid M.B, Durham W.J. Generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in contracting skeletal muscle: potential impact on aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;959:108–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Harde M, Potter B.V.L, Galione A, Stanton P.K. Induction of hippocampal LTD requires nitric-oxide-stimulated PKG activity and Ca2+ release from cyclic ADP-ribose-sensitive stores. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1569–1576. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios E, Pizarro G. Voltage sensor of excitation–contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rev. 1991;71:849–908. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodney G.G, Williams B.Y, Strasburg G.M, Beckingham K, Hamilton S.L. Regulation of RYR1 activity by Ca2+ and calmodulin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7807–7812. doi: 10.1021/bi0005660. 10.1021/bi0005660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodney G.G, Krol J, Williams B, Beckingham K, Hamilton S.L. The carboxy-terminal calcium binding sites of calmodulin control calmodulin's switch from an activator to an inhibitor of RYR1. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12 430–12 435. doi: 10.1021/bi011078a. 10.1021/bi011078a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Mcfadden G, Greenberg M.E. Membrane depolarization and calcium induce c-fos transcription via phosphorylation of transcription factor CREB. Neuron. 1990;4:571–582. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90115-v. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90115-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirokova N, Garcia J, Rios E. Local calcium release in mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 1998;512:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.377be.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.377be.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A.J, Kogan J.H, Frankland P.W, Kida S. CREB and memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1998;21:127–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.127. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P.B, Challiss R.A, Nahorski S.R. Neuronal Ca2+ stores: activation and function. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93919-o. 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93919-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stofan D.A, Callahan L.A, Dimarco A.F, Nethery D.E, Supinski G.S. Modulation of release of reactive oxygen species by the contracting diaphragm. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;161:891–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanovsky D, Murphy T, Anno P.R, Kim Y.M, Salama G. Nitric oxide activates skeletal and cardiac ryanodine receptors. Cell Calcium. 1997;21:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90093-2. 10.1016/S0143-4160(97)90093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suko J, Drobny H, Hellmann G. Activation and inhibition of purified skeletal muscle calcium release channel by NO donors in single channel current recordings. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1451:271–287. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00098-1. 10.1016/S0167-4889(99)00098-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xu L, Eu J.P, Stamler J.S, Meissner G. Classes of thiols that influence the activity of the skeletal muscle calcium release channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2001a;276:15 625–15 630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100083200. 10.1074/jbc.M100083200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xin C, Eu J.P, Stamler J.S, Meissner G. Cysteine-3635 is responsible for skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor modulation by NO. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001b;98:11 158–11 162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201289098. 10.1073/pnas.201289098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xu L, Eu J.P, Stamler J.S, Meissner G. Nitric oxide, NOC-12, and S-nitrosoglutathione modulate the skeletal muscle calcium release channel/ryanodine receptor by different mechanisms. An allosteric function for O2 in S-nitrosylation of the channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:8184–8189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211940200. 10.1074/jbc.M211940200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima H, et al. Primary structure and expression from complementary DNA of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Nature. 1989;339:439–445. doi: 10.1038/339439a0. 10.1038/339439a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Ingalls C.P, Durham W.J, Snider J, Reid M.B, Wu G, Matzuk M.M, Hamilton S.L. Altered excitation–contraction coupling with skeletal muscle specific FKBP12 deficiency. FASEB J. 2004;18:1597–1599. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1587fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X, Finkbeiner S, Arnold D, Shaywitz A.J, Greenberg M.E. Ca2+ influx regulates BDNF transcription by a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Neuron. 1998;20:709–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81010-7. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81010-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E, Klann E. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;12:327–345. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2001.12.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E, Urban N.N, González-Burgos G.R, Kanterewicz B.I, Barrionuevo G, Chu C.T, Ourv T.D, Klann E. Impairment of long-term potentiation and associative memory in mice that overexpress extracellular superoxide dismutase. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7631–7639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07631.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy A, Xu L, Mann G, Meissner G. Calmodulin activation and inhibition of skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) Biophys. J. 1995;69:106–119. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79880-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium signaling in nerve cells. Biol. Res. 2004;37:693–699. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000400027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Petersen O.H. The endoplasmic reticulum as an integrating signalling organelle: from neuronal signalling to neuronal death. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;447:141–154. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01838-1. 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01838-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Rowan M.J, Anwyl R. Ryanodine produces a low frequency stimulation-induced NMDA receptor-independent long-term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J. Physiol. 1996;495:755–767. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Deisseroth K, Tsien R. Activity-dependent CREB phosphorylation: convergence of a fast, sensitive calmoduline kinase pathway and a slow, less sensitive mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:2808–2813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051634198. 10.1073/pnas.051634198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia R, Stangler T, Abramson J.J. Skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor is a redox sensor with a well defined redox potential that is sensitive to channel modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:36 556–36 561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007613200. 10.1074/jbc.M007613200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia R, Webb J.A, Gnall L.L, Cutler K, Abramson J.J. Skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum contains a NADH-dependent oxidase that generates superoxide. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C215–C221. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00034.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yermolaieva O, Brot N, Weissbach H, Heinemann S.H, Hoshi T. Reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide mediate plasticity of neuronal calcium signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:448–453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.448. 10.1073/pnas.97.1.448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zable A.C, Favero T.G, Abramson J.J. Glutathione modulates ryanodine receptor from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Evidence for redox regulation of the Ca2+ release mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:7069–7077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7069. 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]