Abstract

Specialized subgroups of hypothalamic neurons exhibit specific excitatory or inhibitory electrical responses to changes in extracellular levels of glucose. Glucose-excited neurons were traditionally assumed to employ a ‘β-cell’ glucose-sensing strategy, where glucose elevates cytosolic ATP, which closes KATP channels containing Kir6.2 subunits, causing depolarization and increased excitability. Recent findings indicate that although elements of this canonical model are functional in some hypothalamic cells, this pathway is not universally essential for excitation of glucose-sensing neurons by glucose. Thus glucose-induced excitation of arcuate nucleus neurons was recently reported in mice lacking Kir6.2, and no significant increases in cytosolic ATP levels could be detected in hypothalamic neurons after changes in extracellular glucose. Possible alternative glucose-sensing strategies include electrogenic glucose entry, glucose-induced release of glial lactate, and extracellular glucose receptors. Glucose-induced electrical inhibition is much less understood than excitation, and has been proposed to involve reduction in the depolarizing activity of the Na+/K+ pump, or activation of a hyperpolarizing Cl− current. Investigations of neurotransmitter identities of glucose-sensing neurons are beginning to provide detailed information about their physiological roles. In the mouse lateral hypothalamus, orexin/hypocretin neurons (which promote wakefulness, locomotor activity and foraging) are glucose-inhibited, whereas melanin-concentrating hormone neurons (which promote sleep and energy conservation) are glucose-excited. In the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus, excitatory actions of glucose on anorexigenic POMC neurons in mice have been reported, while the appetite-promoting NPY neurons may be directly inhibited by glucose. These results stress the fundamental importance of hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons in orchestrating sleep-wake cycles, energy expenditure and feeding behaviour.

Keywords: glucose, hypothalamus, neurons, sleep, appetite, body weight

1. Introduction

‘Glucose-sensing’ neurons are specialized cells that respond to changes in extracellular glucose concentration with changes in their firing rate. These sensing responses are specific to glucose-sensing neurons, i.e. they are distinct from the ubiquitous ‘run-out-of-fuel’ silencing of neurons by low glucose (Yang et al. 1999; Mobbs et al. 2001; Routh 2002). Apart from the hypothalamus, glucose-sensing neurons are also present in other brain regions, such as the brainstem (Adachi et al. 1995), but in this review we concentrate on hypothalamic cells. First discovered in the 1960s, hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons comprise subgroups of cells in the lateral, arcuate, and ventromedial hypothalamic regions, and can be either electrically inhibited or excited by elevations in extracellular glucose (Anand et al. 1964; Oomura et al. 1969; Routh 2002; Wang et al. 2004). The activity of these cells is thought to be critical in responding to the ever-changing body energy status with appropriately coordinated changes in hormone release, metabolic rate, food intake and locomotor activity, to ensure that the brain always has adequate glucose (Routh 2002, 2003; Levin et al. 2004; Routh et al. 2004). This is of fundamental importance, because unlike most peripheral tissues, the brain becomes irreversibly damaged if deprived of glucose for only a few minutes. The need for coordinated regulation of metabolism and behaviour, to guarantee present and future provision of adequate concentrations of glucose around central neurons, is probably why the brain itself evolved the means to monitor and respond to changes in glucose, instead of relying on peripheral organs such as the liver.

The biophysical and molecular mechanisms responsible for the effects of glucose on glucose-inhibited and glucose-excited neurons are still a matter of some controversy. The fundamental neurophysiological roles of hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons, i.e. which transmitters these cells use and which regions they innervate, are also only beginning to be understood. In this article, we follow a simple ‘input–processing–output’ conceptual framework to look at some experimental data that may be relevant for understanding the physiological operation of hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons. The aim of this short review is not to present a comprehensive overview of the field, nor to promote or disprove a particular model, but to highlight several possibilities that appear consistent with the currently available evidence. We specifically focus on biophysical, molecular and neurochemical features that may be relevant for physiological operation of glucose-sensing neurons in the lateral, arcuate, and ventromedial regions of the hypothalamus.

2. Input: what changes in glucose comprise physiological stimuli for glucose-sensing neurons?

The nature of changes in ambient glucose that hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons experience under physiological conditions was recently discussed in detail (Routh 2002), and so only some of the key points will be summarized here. As a general rule, the extracellular concentration of glucose in the brain is 10–30% of that in the blood (Silver & Erecinska 1994; Routh 2002; de Vries et al. 2003; Levin et al. 2004), depending on brain region, and basal levels in the hypothalamus appear to be about 1.4 mM (measurements from the ventromedial nucleus of fed rats, de Vries et al. 2003). Changes in glucose in the brain rapidly follow those in the blood (Silver & Erecinska 1994), and the extracellular glucose concentration range in the brain that corresponds to meal-to-meal fluctuation of glucose in the plasma (about 5–8 mM) is expected to be between 1 and 2.5 mM (Routh 2002). Crucially, at least some of the glucose-sensing neurons in the lateral, arcuate and ventromedial hypothalamic regions electrically respond to changes in glucose within the latter concentration range, emphasizing the relevance of these cells for processing normal, physiological changes in glucose (Burdakov et al. 2005; Song & Routh 2005; Wang et al. 2004). It is also noteworthy that glucose-sensing neurons located near regions with a reduced blood–brain barrier (known as circumventricular organs, Ganong 2000), for example, the median eminence region that neighbours the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (Elmquist et al. 1999), may in theory experience much higher glucose concentrations than other brain cells, even approaching those present in the plasma. If this is the case, for glucose-sensing neurons of the arcuate nucleus, high glucose concentrations (greater than 5 mM) may well comprise a physiologically relevant stimulus (Fioramonti et al. 2004). On the other hand, experiments involving very low concentrations of glucose should be interpreted with caution: exposing glucose-sensing neurons to 0 mM glucose is not a good stimulus for studying specific glucose-sensing responses because any neuron will eventually be forced to become electrically silenced in the absence of glucose due to energy depletion (Mobbs et al. 2001; Routh 2002).

3. Processing: converting changes in glucose into changes in neuronal electrical activity

Two populations of hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons exist: those excited and those inhibited by glucose. These neurons are directly sensitive to glucose (i.e. not through modulation of input from presynaptic neurons). Indirect (presynaptic) modulation of hypothalamic neurons by glucose has also been reported (Song et al. 2001; Routh 2002), but will not be discussed here. In this section, we focus on how an elevation in extracellular glucose can be converted into an increase in electrical activity of glucose-excited neurons. How glucose suppresses the electrical activity of glucose-inhibited neurons is understood much less, and was initially proposed to involve a reduction in the depolarizing activity of the electrogenic Na+/K+ pump (Oomura et al. 1974), and more recently, an activation of a hyperpolarizing Cl− current (Routh 2002). However, these possibilities remain to be investigated in detail.

(a) Models of glucose-excited neurons inspired by the pancreatic β-cell

(i) The canonical β-cell model

The insulin-secreting β-cells of the endocrine pancreas, which respond to a rise in extracellular glucose with membrane depolarization (and consequent increase in electrical activity and insulin release), are the best understood glucose-sensing excitable cells. In the canonical β-cell model, glucose enters the cell via the Glut2 transporter, is phosphorylated by glucokinase, and is then processed by the ubiquitous ‘house-keeping’ energy-producing machinery of the cell (Ashcroft & Rorsman 2004). The consequent increase in the cytosolic ATP:ADP concentration ratio in the cytosol then closes the ATP-inhibited K+ channels (KATP) in the plasma membrane. In the β-cell, these channels are made up of Kir6.2 subunits (Ashcroft & Rorsman 2004). Since open KATP channels generate tonic hyperpolarization of the β-cell and so dampen its excitability, their closure results in depolarization and increased electrical activity.

The key glucose-sensing features of this scheme are the glucose transporter Glut2 and glucokinase (hexokinase IV). The Glut2 transporter has a low affinity (high Km) for glucose, which prevents it from saturation within the physiological range of glucose concentrations in the blood. Similarly, glucokinase, unlike the more ubiquitously expressed hexokinase I, has a low affinity for glucose and is not inhibited by its product, glucose-6-phosphate. Together, these two proteins ensure that changes in extracellular glucose levels within the physiological range are converted to proportional changes in the cytosolic ATP:ADP ratio, and hence generate proportional changes in electrical excitability.

(ii) Elements of the β-cell model shape excitability and glucose responses of glucose-excited neurons

The β-cell model influenced numerous investigators to test whether glucose-excited hypothalamic neurons use the same strategy. A large number of these studies were molecular, looking for the rather circumstantial evidence of whether molecules implicated in glucose-sensing in the β-cell are also present in hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons. Expression of Glut2, glucokinase and Kir6.2 was found in some, but not all, glucose-excited neurons (Kang et al. 2004). Furthermore, these molecules were also present in non-glucose-sensing neurons (Lynch et al. 2000). Thus, the molecular support for the idea that all glucose-excited neurons rely on the β-cell tools to sense glucose is currently inconclusive, and several authors agreed that glucose-mediated excitation of neurons is unlikely to be mechanistically identical to that of β-cells (Yang et al. 1999; Levin et al. 2004). If glucose entry into the cell plays a role in hypothalamic glucose-sensing, it is most likely mediated by Glut3, a transporter which is present in glucose-sensing neurons (Kang et al. 2004), and whose Km (1–3 mM) is actually better suited for the low levels of glucose in the brain than that of Glut2 (15–20 mM).

Functional experiments testing whether hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons behave according to a β-cell-like model were also carried out. Pharmacological blockade of glucokinase decreased the activity of glucose-excited neurons (Levin et al. 2004). In turn, in glucose-excited neurons of the ventromedial nucleus, reductions in extracellular glucose levels activated channels with biophysics and pharmacology consistent with KATP channels (Ashford et al. 1990; Wang et al. 2004). Correspondingly, knockout of the Kir6.2 subunit of the KATP channel led to a threefold increase in the spontaneous firing rate of ventromedial hypothalamic neurons, which could not be further increased by glucose (Miki et al. 2001). Together, these experiments are in agreement with the idea that in some glucose-excited neurons, certain molecular components of the β-cell model influence excitability and glucose-sensing. However, in neurons of the arcuate nucleus the knockout of Kir6.2 did not abolish glucose-induced excitation (Fioramonti et al. 2004). Thus, although the Kir6.2-containing KATP channel may in certain cases play a vital role in glucose-sensing carried out by hypothalamic neurons, it is clearly not universally essential for glucose-induced excitation.

Perhaps the most critical observation required to validate any β-cell-like model is that increases in extracellular glucose concentration should be converted into elevations in cytosolic ATP levels. Cytosolic ATP changes can be monitored using genetically targeted luciferases, and this approach revealed robust glucose-induced elevations in cytosolic ATP in β-cells, hypothalamic glia, and cerebellar neurons (Kennedy et al. 1999; Ainscow & Rutter 2002; Ainscow et al. 2002). However, the same authors did not detect glucose-induced increased in cytosolic ATP in hypothalamic neurons (Ainscow et al. 2002). Moreover, when the cytosol of hypothalamic neurons was continuously perfused with a high concentration of ATP (via the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration), a reduction in extracellular glucose was still able to induce membrane hyperpolarization (Ainscow et al. 2002). Such experiments question the usefulness of β-cell-based models as a framework for understanding hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons.

(b) Glucose sensing without intracellular glucose metabolism

The idea that intracellular glucose metabolism is a crucial component of specific neuronal sensing of glucose, by analogy with the influential β-cell model described above, has been a popular assumption in many studies. However, there is no a priori reason why glucose-sensing neurons should use their housekeeping intracellular energy-producing machinery as a specific signalling pathway for converting changes in extracellular glucose into changes in electrical activity. Intracellular ATP metabolism is a general, ubiquitous process ultimately essential for maintaining any electrical response of an excitable cell, but, as discussed above, the idea that it is more specifically involved in neuronal glucose-sensing is currently not supported by experimental data. In fact, metabolizing glucose would be a rather unusual way of generating a neuron-specific electrical response, since the specific action of most other modulators of neuronal excitability (neurotransmitters, neuropeptides, hormones) does not require metabolizing the stimulus itself. So is there any evidence that, like most other chemical stimuli that affect neuronal excitability, changes in glucose could themselves trigger specific changes in electrical activity, without having to generate corresponding ‘signalling’ changes in ATP?

(i) Electrogenic glucose entry

One potential mechanism for how this may occur is electrogenic translocation of glucose across the plasma membrane, where the entry of (electrically neutral) glucose is directly coupled to transmembrane movement of ions. For example, the sodium–glucose co-transporters (SGLTs) move glucose together with Na+ ions, and so generate inward currents in the process of transporting glucose into cells, resulting in depolarization and increased excitability (Elsas & Longo 1992). This potentially provides a simple and direct way to convert fluctuations in glucose levels into changes in electrical activity, since the electrochemical force for SGLT-mediated Na+ entry, and hence the magnitude of Na+ current, are directly determined by the extracellular glucose concentration. This mechanism was recently demonstrated to be involved in glucose-induced excitation of intestinal cells that secrete glucagon-like peptide 1 (Gribble et al. 2003). A comprehensive experimental evaluation of whether such a mechanism might operate in glucose-sensing neurons has not yet been carried out, but the data collected so far appear consistent with this idea. For example, intracerebroventricular injection of the SGLT inhibitor phloridzin stimulated feeding in rodents (Glick & Mayer 1968; Tsujii & Bray 1990), and inhibited glucose-induced excitation of ventromedial hypothalamic neurons in brain slice preparations (Yang et al. 1999). Incidentally, it is noteworthy that the phenomenon of reversal potential observed for the glucose-induced current in glucose-excited neurons of the arcuate nucleus (Fioramonti et al. 2004) could be consistent not only with a non-selective cation channel, but also with an electrogenic co-transporter or exchanger, which, like ion channels, exhibit electrochemical reversal potentials according to basic thermodynamic laws (e.g. Blaustein & Lederer 1999).

(ii) Glucose receptors: specific non-transporting detectors of extracellular glucose

There is no a priori reason for why glucose has to get inside a neuron in order to change the latter's electrical activity. After all, most other extracellular messengers alter electrical activity of neurons not by entering the cytosol but by binding to specific extracellular receptors that, either directly or via intracellular signal transduction cascades, control transmembrane fluxes of ions. Is there any evidence that specialized ‘glucose receptors’ exist in glucose-sensing cells, that can convert changes in extracellular glucose into changes in electrical activity without transporting the sugar? Recently, Diez-Sampedro et al. (2003) identified a mammalian glucose transporter homologue, SGLT3/SLC5A4, that is expressed in the plasma membrane but does not transport glucose into the cell. Instead, this protein acted as a sensing receptor, converting elevations in extracellular glucose into Na+-dependent depolarization of the membrane (Diez-Sampedro et al. 2003). The expression of this glucose sensor was detected in some peripheral neurons (Diez-Sampedro et al. 2003), and it would be important to examine its potential expression and function in hypothalamic glucose-sensing cells. Several other glucose sensors were recently identified that operate independently of glucose transport and metabolism, including G-protein coupled receptors and the mammalian Glut1 carrier (Holsbeeks et al. 2004). While it remains to be examined whether such signalling pathways are involved in glucose-induced electrical responses of hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons, these recent experiments make it clear that glucose entry into the cell is not a necessary prerequisite for specific glucose-sensing. At least in some cases, glucose-sensing can operate analogously to the classical specific sensing systems for neurotransmitters and neuropeptides.

(iii) Hypothalamic astrocytes as primary detectors of glucose changes?

Although astroglial cells (astrocytes) were for a long-time viewed as purely supporting, passive elements of the brain, it is now clear that they directly respond to diverse physiological stimuli, bi-directionally communicate with neurons, and play an active role in central information processing (Verkhratsky et al. 1998; Araque et al. 2001; Nedergaard et al. 2003). Can astrocytes be the primary physiological detectors of extracellular glucose changes, with glucose-sensing neurons acting as downstream effectors? This intriguing possibility was suggested by data of Ainscow and co-workers, who reported that hypothalamic glia (but not hypothalamic neurons) respond to a rise in extracellular glucose with a large increase in glycolytic ATP production, which would be expected to lead to glial release of lactate (Ainscow et al. 2002; Pellerin & Magistretti 2004). They also showed that both hypothalamic neurons and glia express high levels of the lactate transporter MCT1, and that lactate elevates cytoslic ATP levels and closes KATP channels in hypothalamic neurons (Ainscow et al. 2002). These results inspired models where, upon a rise in extracellular glucose, glia produce lactate, which is transported from glia and into neurons by MCT1, and consequently depolarizes and excites the neurons by closing the KATP channels (Ainscow et al. 2002; Burdakov & Ashcroft 2002). The latter prediction was recently supported by the observation that lactate has excitatory actions on glucose-excited neurons of the ventromedial nucleus, but not on non-glucose-sensing neurons (Song & Routh 2005). In turn, pharmacological disruption of metabolic coupling between neurons and astrocytes in vivo prevented glucose-induced c-fos activation of ARC neurons (Guillod-Maximin et al. 2004), and the MCT1 transporter was found in some glucose-sensing neurons of the ventromedial nucleus (Kang et al. 2004). There is thus considerable evidence in support of the idea that hypothalamic astrocytes may play a role in excitation of hypothalamic neurons by glucose. However, the fact that glucose-sensing responses of hypothalamic neurons could be observed in isolated cell preparations (Ainscow et al. 2002; Kang et al. 2004), where the low cell density probably precludes neuron–glia interactions, suggests that astrocytes are not essential for hypothalamic glucose-sensing, and are likely to play a more complementary role.

4. Output: neurotransmitter identities and projection targets of glucose-sensing neurons

The neurotransmitter identities, and thus the exact neurophysiological roles, of hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons remained unclear for many years after their discovery. However, recent advances in hypothalamic neurochemistry and consequent design of animal models that allow targeted recordings from neurochemically defined populations of neurons are helping to reveal fundamental information about transmitter identities and projection targets of these cells.

(a) Lateral hypothalamic neurons

Considerable experimental attention was recently attracted by a newly discovered subset of lateral hypothalamic neurons, those that contain the peptide transmitters orexins/hypocretins (de Lecea et al. 1998; Sakurai et al. 1998). Orexinergic projections were found widely throughout the brain, with especially dense innervation of areas that regulate arousal, appetite and metabolism (Peyron et al. 1998). Lack of orexins or of orexin neurons caused the symptoms of narcolepsy/cataplexy (intrusions of rapid-eye-movement sleep and sleep paralysis into normal wakefulness), hypophagia, and late-onset obesity (Chemelli et al. 1999; Hara et al. 2001). Orexin neurons appeared to be more active during wakefulness and relatively silent during slow-wave sleep (Estabrooke et al. 2001; Kiyashchenko et al. 2002). In turn, central administration of orexins stimulated wakefulness, sympathetic nervous system activity, food intake and locomotor activity (reviewed in Siegel 2004; Willie et al. 2001; Sutcliffe & de Lecea 2002; Taheri et al. 2002; Taylor & Samson 2003).

Initial experiments examining the effects of glucose on the lateral hypothalamic neurons of the rat suggested that orexin-A was not expressed in neurons that exhibited electrical responses to glucose (Liu et al. 2001). However, another study, published more or less simultaneously, found that glucose inhibits intracellular calcium signals in a substantial fraction of isolated rat orexin neurons (Muroya et al. 2001), indicating that at least some lateral hypothalamic orexin cells display glucose-sensing properties. Subsequent electrophysiological recordings from isolated mouse orexin neurons were consistent with the latter data from rat orexin neurons, and convincingly demonstrated that the majority (80–100%) of orexin neurons are directly hyperpolarized and inhibited by glucose, albeit in a supra-physiological (>5 mM) concentration range (Yamanaka et al. 2003). More recently, we found that physiological concentrations of glucose (0.2–5 mM) directly hyperpolarize and inhibit most (ca 95%) mouse orexin neurons in situ, in lateral hypothalamic brain slice preparations (Burdakov et al. 2005). Thus, the balance of evidence currently suggests that the wake-promoting activity of orexin neurons would be inhibited by a rise in glucose, and stimulated by a fall in glucose. The finding that mice whose orexin neurons are specifically destroyed failed to respond to fasting with increased wakefulness and activity (Yamanaka et al. 2003) is consistent with this idea.

Another population of lateral hypothalamic cells that attracted much recent attention are neurons that use the peptide transmitter melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH). Like orexin neurons, MCH neurons project widely throughout the brain (Bittencourt et al. 1992), but, in many respects, their physiological roles seem to be the opposite of those of orexin cells. In mice, knockout of MCH increased metabolic rate (measured as rate of oxygen consumption per unit body weight) and reduced body weight (Shimada et al. 1998); these characteristics were shared by animals lacking the MCH receptor MCH1R (Marsh et al. 2002). Intracerebroventricular injection of MCH in rats dose-dependently increased the quantities of rapid-eye-movement and slow wave sleep (Verret et al. 2003), and ablation of prepro-MCH or MCH1R in mice led to enhanced wheel running activity (Zhou et al. 2005). These data suggest that the release of endogenous MCH promotes sleep and suppresses locomotor activity and energy expenditure. The role of MCH in the control of food intake is less clear. In mice, knockout of MCH increased food intake during the day, but decreased it during the night, with the net (whole-day) result being a reduction in food intake (Shimada et al. 1998). Originally, central administration of MCH in rats was reported to either reduce (Presse et al. 1996) or increase (Qu et al. 1996) food intake. Similar studies performed later were more consistent with the latter finding, and indicated that central injection of MCH increases food intake in rats (Rossi et al. 1997) and mice (Marsh et al. 2002). Therefore, it was surprising that mice missing MCHR1 receptor, which is essential for hyperphagia observed upon chronic central administration of MCH (Marsh et al. 2002), exhibited increased food intake (Chen et al. 2002; Marsh et al. 2002). Yet, systemic or central administration of an MCHR1 antagonist reduced food intake (Borowsky et al. 2002; Georgescu et al. 2005). Physiological effects of MCH on appetite thus appear to be complex, especially considering that MCH may also regulate anxiety and depression (Borowsky et al. 2002; Georgescu et al. 2005).

Our recent examination of the effects of changes in glucose on the electrical excitability of MCH neurons in mouse brain slices indicated that most (ca 80%) of MCH neurons are directly and dose-dependently depolarized and excited by glucose within the physiological concentration range (Burdakov et al. 2005). Based on the above-mentioned effects of MCH on locomotor activity and body energy balance, these data imply that glucose-induced excitation of MCH neurons may promote sleep and suppress energy expenditure.

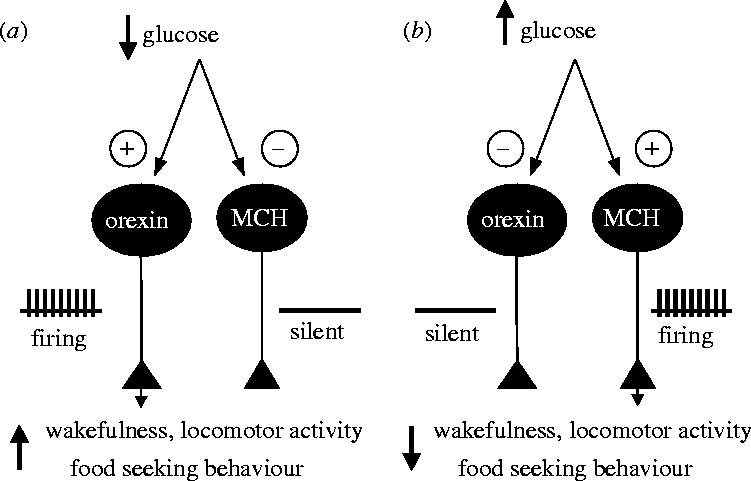

With regards to physiological implications, these findings make the orexin and MCH neurons of the lateral hypothalamus perhaps the best understood glucose-sensing cells to date. The opposite effects of glucose on orexin and MCH neurons are consistent with a simple model where physiological changes in brain extracellular glucose can directly control sleep–wake behaviour and energy expenditure (figure 1). It is tempting to speculate that these interactions may be involved in the well documented but poorly understood phenomena of hunger-induced arousal and after-meal sleepiness.

Figure 1.

Model for how actions of glucose on neurons of the lateral hypothalamus may regulate sleep and feeding behaviour. (a) When body energy resources are low, extracellular glucose concentration falls. This increases the electrical activity of orexin neurons (which are inhibited by glucose), but suppresses the excitability of MCH neurons. Consequent increased release of orexin and decreased release of MCH stimulates wakefulness, appetite and activity, leading to foraging and feeding. (b) When body energy supplies are high, elevated extracellular glucose inhibits orexin neurons and activates MCH neurons, leading to increased sleepiness, and decreased metabolism and activity. See test for details.

(b) Arcuate nucleus neurons

On the electrophysiological and molecular levels, at present the arcuate nucleus is probably the best understood brain region in relation to central control of appetite and metabolism. The widely accepted model today is that the activity of arcuate neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons promotes weight gain by stimulating appetite and suppressing energy expenditure, whereas arcuate neurons that contain proopiomelanocortin (POMC) cause weight loss by inhibiting feeding and stimulating energy expenditure (Schwartz et al. 2000; Cone et al. 2001). These actions are thought to be mediated by the projections from arcuate NPY and POMC neurons to numerous CNS regions that control appetite and metabolism (reviewed in Elmquist et al. 1999; Kalra et al. 1999; Schwartz et al. 2000; Cone et al. 2001). A crucial feature of this influential model is that the activity of NPY and POMC cells is oppositely regulated by signals of body energy status, and this ‘push–pull’ synergism avoids contradictory influences of NPY and POMC neurons (Schwartz et al. 2000; Cone et al. 2001). For example, the appetite-suppressing hormone leptin electrically excited POMC neurons and inhibited NPY neurons, while the appetite-enhancing hormone ghrelin inhibited POMC neurons but activated NPY neurons (Cowley et al. 2001, 2003; van den Top et al. 2004).

Does glucose, a signal of energy plenty, excite POMC neurons and inhibit NPY neurons? Although the data collected to date are not plentiful, there are some experimental results that are consistent with this idea. Muroya et al. (1999) found that lowering extracellular glucose concentration increased cytosolic calcium signals in neurons isolated from the rat arcuate nucleus, and 94% of these cells were immunoreactive for NPY. Because increased cytosolic calcium levels can be caused by increased spike firing rate, this suggests that firing of arcuate NPY neurons is directly inhibited by glucose, yet this remains to be validated by recordings of electrical activity in synaptically isolated arcuate NPY cells. For arcuate POMC neurons, electrophysiological effects of glucose were investigated in both mice and rats. Ibrahim et al. (2003), using whole-cell and cell-attached patch-clamp recordings in mouse brain slices, found that ca 80% of POMC neurons (identified for recordings by transgenic eGFP fluorescence) were excited by glucose, but whether this effect was direct or presynaptic was not established. However, Wang et al. (2004), using whole-cell recordings and post-recording POMC immunolabelling in rat brain slices, did not detect POMC in 8/8 glucose-excited neurons. This possible discrepancy may be indicative of species differences (mouse versus rat), but, perhaps more likely, it reflects the possibility that only a subpopulation of POMC neurons are glucose-excited.

(c) Ventromedial nucleus neurons

From the discovery of hypothalamic glucose-sensing cells until the present, the neurons of the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus were the most popular experimental target for investigators interested in hypothalamic sensing of glucose. However, while these cells and their responses to glucose are undoubtedly very important for body energy balance, the ventromedial neurons remain probably the least understood hypothalamic glucose-sensing cells with regards to their projection targets and neurochemical identity. This is likely because no endogenous neurochemical marker that is relatively specific for soma and terminals of ventromedial neurons was yet discovered, in contrast to arcuate neurons (which contain POMC or NPY) and neurons of the lateral hypothalamus (which contain orexins or MCH). Single cell RT-PCR studies indicated that some, if not all, ventromedial hypothalamic neurons, including glucose-excited neurons, are GABAergic (Miki et al. 2001; Kang et al. 2004). The physiological implications of these findings would depend on the innervation targets of these glucose-modulated GABAergic cells, which are currently unknown.

5. Concluding remarks

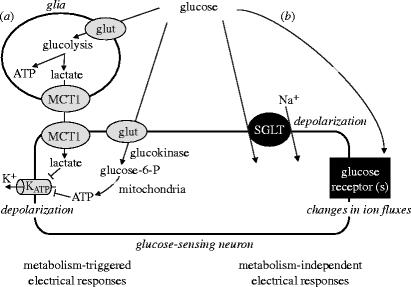

The biophysical mechanisms underlying the specific glucose-sensing responses of hypothalamic neurons are still controversial, and several possibilities exist at present (figure 2). These general mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and glucose-sensing neurons may well use a combination of such pathways. It is also possible that different glucose-sensing mechanisms could be used by different populations of hypothalamic glucose-sensing cells, and possibly even by the same neuron for different parts of the physiological spectrum of glucose levels. For example, metabolism-based pathways (figure 2) may be best suited for detection of severe hypoglycaemia, whereas metabolism-independent sensing (figure 2) may provide a good strategy for reliable conversion of small changes in extracellular glucose into electrical responses. While much remains to be learnt about the biophysical strategies of neuronal sensing of glucose, recent localization of specific glucose-sensing responses to neurochemically and behaviourally defined hypothalamic neurons emphasizes fundamental roles of these cells in the control of sleep, appetite and body weight.

Figure 2.

Multiple pathways are likely to be involved in the modulation of the electrical activity of hypothalamic neurons by glucose. (a) Glucose, acting as an energy substrate, can alter neuronal electrical activity by influencing energy metabolism inside neurons and glia. (b) Glucose, acting as an extracellular signalling messenger, can also activate specific glucose receptors that control membrane ion fluxes, or can itself be transported by electrogenic transporters. Which of these general mechanisms is dominant in different glucose-sensing neurons remains to be determined. See text for details.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Stephen St George-Smith (University of Manchester) for useful discussions. DB is supported by a Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

One contribution of 18 to a Theme Issue ‘Reactive oxygen species in health and disease’.

References

- Adachi A, Kobashi M, Funahashi M. Glucose-responsive neurons in the brainstem. Obes. Res. 1995;3(Suppl. 5):735–740. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow E.K, Rutter G.A. Glucose-stimulated oscillations in free cytosolic ATP concentration imaged in single islet beta-cells: evidence for a Ca2+-dependent mechanism. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl. 1):162–170. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow E.K, Mirshamsi S, Tang T, Ashford M.L, Rutter G.A. Dynamic imaging of free cytosolic ATP concentration during fuel sensing by rat hypothalamic neurones: evidence for ATP-independent control of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. J. Physiol. 2002;544:429–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022434. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand B.K, Chhina G.S, Sharma K.N, Dua S, Singh B. Activity of single neurons in the hypothalamic feeding centers: effect of glucose. Am. J. Physiol. 1964;207:1146–1154. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.207.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon P.G. Dynamic signaling between astrocytes and neurons. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:795–813. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.795. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft F, Rorsman P. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: not quite exciting enough? Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:R21–R31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh066. 10.1093/hmg/ddh066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford M.L, Boden P.R, Treherne J.M. Glucose-induced excitation of hypothalamic neurones is mediated by ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Pflug. Arch. 1990;415:479–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00373626. 10.1007/BF00373626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt J.C, Presse F, Arias C, Peto C, Vaughan J, Nahon J.L, Vale W, Sawchenko P.E. The melanin-concentrating hormone system of the rat brain: an immuno- and hybridization histochemical characterization. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;319:218–245. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190204. 10.1002/cne.903190204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein M.P, Lederer W.J. Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:763–854. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky B, et al. Antidepressant, anxiolytic and anorectic effects of a melanin-concentrating hormone-1 receptor antagonist. Nat. Med. 2002;8:825–830. doi: 10.1038/nm741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdakov D, Ashcroft F.M. Shedding new light on brain metabolism and glial function. J. Physiol. 2002;544:334. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029090. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdakov D, Gerasimenko O, Verkhratsky A. Physiological changes in glucose differentially modulate the excitability of hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone and orexin neurons in situ. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2429–2433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4925-04.2005. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4925-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli R.M, et al. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81973-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. Targeted disruption of the melanin-concentrating hormone receptor-1 results in hyperphagia and resistance to diet-induced obesity. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2469–2477. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8903. 10.1210/en.143.7.2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone R.D, Cowley M.A, Butler A.A, Fan W, Marks D.L, Low M.J. The arcuate nucleus as a conduit for diverse signals relevant to energy homeostasis. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2001;25(Suppl. 5):S63–S67. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley M.A, Smart J.L, Rubinstein M, Cerdan M.G, Diano S, Horvath T.L, Cone R.D, Low M.J. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411:480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. 10.1038/35078085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley M.A, et al. The distribution and mechanism of action of ghrelin in the CNS demonstrates a novel hypothalamic circuit regulating energy homeostasis. Neuron. 2003;37:649–661. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00063-1. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00063-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, et al. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries M.G, Arseneau L.M, Lawson M.E, Beverly J.L. Extracellular glucose in rat ventromedial hypothalamus during acute and recurrent hypoglycemia. Diabetes. 2003;52:2767–2773. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Sampedro A, Hirayama B.A, Osswald C, Gorboulev V, Baumgarten K, Volk C, Wright E.M, Koepsell H. A glucose sensor hiding in a family of transporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11753–11758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733027100. 10.1073/pnas.1733027100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist J.K, Elias C.F, Saper C.B. From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Neuron. 1999;22:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81084-3. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81084-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsas L.J, Longo N. Glucose transporters. Annu. Rev. Med. 1992;43:377–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.002113. 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.002113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooke I.V, McCarthy M.T, Ko E, Chou T.C, Chemelli R.M, Yanagisawa M, Saper C.B, Scammell T.E. Fos expression in orexin neurons varies with behavioral state. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1656–1662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioramonti X, Lorsignol A, Taupignon A, Penicaud L. A new ATP-sensitive K+ channel-independent mechanism is involved in glucose-excited neurons of mouse arcuate nucleus. Diabetes. 2004;53:2767–2775. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganong W.F. Circumventricular organs: definition and role in the regulation of endocrine and autonomic function. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2000;27:422–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03259.x. 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu D, et al. The hypothalamic neuropeptide melanin-concentrating hormone acts in the nucleus accumbens to modulate feeding behavior and forced-swim performance. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2933–2940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1714-04.2005. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1714-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick Z, Mayer J. Hyperphagia caused by cerebral ventricular infusion of phloridzin. Nature. 1968;219:1374. doi: 10.1038/2191374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M, Williams L, Simpson A.K, Reimann F. A novel glucose-sensing mechanism contributing to glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from the GLUTag cell line. Diabetes. 2003;52:1147–1154. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillod-Maximin E, Lorsignol A, Alquier T, Penicaud L. Acute intracarotid glucose injection towards the brain induces specific c-fos activation in hypothalamic nuclei: involvement of astrocytes in cerebral glucose-sensing in rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:464–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01185.x. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, et al. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron. 2001;30:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00293-8. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00293-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsbeeks I, Lagatie O, Van Nuland A, Van de Velde S, Thevelein J.M. The eukaryotic plasma membrane as a nutrient-sensing device. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.08.010. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim N, Bosch M.A, Smart J.L, Qiu J, Rubinstein M, Ronnekleiv O.K, Low M.J, Kelly M.J. Hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons are glucose responsive and express K(ATP) channels. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1331–1340. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221033. 10.1210/en.2002-221033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra S.P, Dube M.G, Pu S, Xu B, Horvath T.L, Kalra P.S. Interacting appetite-regulating pathways in the hypothalamic regulation of body weight. Endocr. Rev. 1999;20:68–100. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.1.0357. 10.1210/er.20.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L, Routh V.H, Kuzhikandathil E.V, Gaspers L.D, Levin B.E. Physiological and molecular characteristics of rat hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus glucosensing neurons. Diabetes. 2004;53:549–559. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H.J, Pouli A.E, Ainscow E.K, Jouaville L.S, Rizzuto R, Rutter G.A. Glucose generates sub-plasma membrane ATP microdomains in single islet beta-cells. Potential role for strategically located mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13281–13291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13281. 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyashchenko L.I, Mileykovskiy B.Y, Maidment N, Lam H.A, Wu M.F, John J, Peever J, Siegel J.M. Release of hypocretin (orexin) during waking and sleep states. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5282–5286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05282.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin B.E, Routh V.H, Kang L, Sanders N.M, Dunn-Meynell A.A. Neuronal glucosensing: what do we know after 50 years? Diabetes. 2004;53:2521–2528. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.H, Morris R, Spiller D, White M, Williams G. Orexin a preferentially excites glucose-sensitive neurons in the lateral hypothalamus of the rat in vitro. Diabetes. 2001;50:2431–2437. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch R.M, Tompkins L.S, Brooks H.L, Dunn-Meynell A.A, Levin B.E. Localization of glucokinase gene expression in the rat brain. Diabetes. 2000;49:693–700. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D.J, et al. Melanin-concentrating hormone 1 receptor-deficient mice are lean, hyperactive, and hyperphagic and have altered metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3240–3245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706899. 10.1073/pnas.052706899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, et al. ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the hypothalamus are essential for the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:507–512. doi: 10.1038/87455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs C.V, Kow L.M, Yang X.J. Brain glucose-sensing mechanisms: ubiquitous silencing by aglycemia vs. hypothalamic neuroendocrine responses. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;281:E649–E654. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.4.E649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroya S, Yada T, Shioda S, Takigawa M. Glucose-sensitive neurons in the rat arcuate nucleus contain neuropeptide Y. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;264:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00185-8. 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00185-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroya S, Uramura K, Sakurai T, Takigawa M, Yada T. Lowering glucose concentrations increases cytosolic Ca2+ in orexin neurons of the rat lateral hypothalamus. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;309:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02053-5. 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02053-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M, Ransom B, Goldman S.A. New roles for astrocytes: redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008. 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomura Y, Ono T, Ooyama H, Wayner M.J. Glucose and osmosensitive neurones of the rat hypothalamus. Nature. 1969;222:282–284. doi: 10.1038/222282a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomura Y, Ooyama H, Sugimori M, Nakamura T, Yamada Y. Glucose inhibition of the glucose-sensitive neurone in the rat lateral hypothalamus. Nature. 1974;247:284–286. doi: 10.1038/247284a0. 10.1038/247284a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin L, Magistretti P.J. Neuroenergetics: calling upon astrocytes to satisfy hungry neurons. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:53–62. doi: 10.1177/1073858403260159. 10.1177/1073858403260159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe D.K, van den Pol A.N, de Lecea L, Heller H.C, Sutcliffe J.G, Kilduff T.S. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presse F, Sorokovsky I, Max J.P, Nicolaidis S, Nahon J.L. Melanin-concentrating hormone is a potent anorectic peptide regulated by food-deprivation and glucopenia in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;71:735–745. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00481-5. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00481-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu D, et al. A role for melanin-concentrating hormone in the central regulation of feeding behaviour. Nature. 1996;380:243–247. doi: 10.1038/380243a0. 10.1038/380243a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Choi S.J, O'Shea D, Miyoshi T, Ghatei M.A, Bloom S.R. Melanin-concentrating hormone acutely stimulates feeding, but chronic administration has no effect on body weight. Endocrinology. 1997;138:351–355. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4887. 10.1210/en.138.1.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routh V.H. Glucose-sensing neurons: are they physiologically relevant? Physiol. Behav. 2002;76:403–413. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00761-8. 10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00761-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routh V.H. Glucosensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMN) and hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure (HAAF) Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2003;19:348–356. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.404. 10.1002/dmrr.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routh V.H, Song Z, Liu X. The role of glucosensing neurons in the detection of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2004;6:413–421. doi: 10.1089/152091504774198133. 10.1089/152091504774198133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80949-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M.W, Woods S.C, Porte D, Jr, Seeley R.J, Baskin D.G. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404:661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Tritos N.A, Lowell B.B, Flier J.S, Maratos-Flier E. Mice lacking melanin-concentrating hormone are hypophagic and lean. Nature. 1998;396:670–674. doi: 10.1038/25341. 10.1038/25341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J.M. Hypocretin (orexin): role in normal behavior and neuropathology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004;55:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141545. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver I.A, Erecinska M. Extracellular glucose concentration in mammalian brain: continuous monitoring of changes during increased neuronal activity and upon limitation in oxygen supply in normo-, hypo-, and hyperglycemic animals. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:5068–5076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-05068.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Routh V.H. Differential effects of glucose and lactate on glucosensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Diabetes. 2005;54:15–22. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Levin B.E, McArdle J.J, Bakhos N, Routh V.H. Convergence of pre- and postsynaptic influences on glucosensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Diabetes. 2001;50:2673–2681. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe J.G, de Lecea L. The hypocretins: setting the arousal threshold. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:339–349. doi: 10.1038/nrn808. 10.1038/nrn808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri S, Zeitzer J.M, Mignot E. The role of hypocretins (orexins) in sleep regulation and narcolepsy. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;25:283–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142826. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M.M, Samson W.K. The other side of the orexins: endocrine and metabolic actions. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;284:E13–E17. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00359.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujii S, Bray G.A. Effects of glucose, 2-deoxyglucose, phlorizin, and insulin on food intake of lean and fatty rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:E476–E481. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.3.E476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Top M, Lee K, Whyment A.D, Blanks A.M, Spanswick D. Orexigen-sensitive NPY/AgRP pacemaker neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:493–494. doi: 10.1038/nn1226. 10.1038/nn1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Orkand R.K, Kettenmann H. Glial calcium: homeostasis and signaling function. Physiol. Rev. 1998;78:99–141. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verret L, et al. A role of melanin-concentrating hormone producing neurons in the central regulation of paradoxical sleep. BMC Neurosci. 2003;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-4-19. 10.1186/1471-2202-4-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Liu X, Hentges S.T, Dunn-Meynell A.A, Levin B.E, Wang W, Routh V.H. The regulation of glucose-excited neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus by glucose and feeding-relevant peptides. Diabetes. 2004;53:1959–1965. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie J.T, Chemelli R.M, Sinton C.M, Yanagisawa M. To eat or to sleep? Orexin in the regulation of feeding and wakefulness. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:429–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.429. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, et al. Hypothalamic orexin neurons regulate arousal according to energy balance in mice. Neuron. 2003;38:701–713. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00331-3. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00331-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.J, Kow L.M, Funabashi T, Mobbs C.V. Hypothalamic glucose sensor: similarities to and differences from pancreatic beta-cell mechanisms. Diabetes. 1999;48:1763–1772. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Shen Z, Strack A.M, Marsh D.J, Shearman L.P. Enhanced running wheel activity of both Mch1r- and Pmch-deficient mice. Regul. Pept. 2005;124:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.06.026. 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]