Abstract

The medaka, Oryzias latipes, has an XX/XY sex-determination mechanism. A Y-linked DM domain gene, DMY, has been isolated by positional cloning as a sex-determining gene in this species. Previously, we found 23 XY sex-reversed females from 11 localities by examining the genotypic sex of wild-caught medaka. Genetic analyses revealed that all these females had Y-linked gene mutations. Here, we aimed to clarify the cause of this sex reversal. To achieve this, we screened for mutations in the amino acid coding sequence of DMY and examined DMY expression at 0 days after hatching (dah) using densitometric semiquantitative RT–PCR. We found that the mutants could be classified into two groups. One contained mutations in the amino acid coding sequence of DMY, while the other had reduced DMY expression at 0 dah although the DMY coding sequence was normal. For the latter, histological analyses indicated that YwOurYwOur (YwOur, Y chromosome derived from an Oura XY female) individuals with the lowest DMY expression among the tested mutants were expected to develop into females at 0 dah. These results suggest that early testis development requires DMY expression above a threshold level. Mutants with reduced DMY expression may prove valuable for identifying DMY regulatory elements.

IN vertebrates, the sex of an individual is established by the sex of the gonad and, in most cases, whether a gonad becomes a testis or an ovary is determined by the genome of that individual. In most mammals, the Y chromosome-specific gene SRY/Sry is the master male-determining gene (Gubbay et al. 1990; Sinclair et al. 1990; Koopman et al. 1991). The SRY gene encodes a testis-specific transcription factor that plays a key role in sexual differentiation and development in males (Lovell-Badge et al. 2002). Non-mammalian vertebrates also have a male heterogametic (XX–XY) sex-determination system, but no homolog of Sry could be found.

In the teleost medaka fish, Oryzias latipes, which has an XX–XY sex-determining system (Aida 1921), DMY (DM domain gene on the Y chromosome) has been found in the sex-determining region on the Y chromosome (Matsuda et al. 2002; Nanda et al. 2002). This gene is the first sex-determining gene to be found among non-mammalian vertebrates. DMY encodes a protein containing a DM domain, which is a DNA-binding motif found in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans (DSX and MAB-3, respectively) that is involved in sexual development (Raymond et al. 1998). The cDNA sequences of medaka DMY and DMRT1 are highly similar and DMY appears to have originated through duplication of an autosomal segment containing the DMRT1 region (Nanda et al. 2002; Kondo et al. 2004). DMY is specifically expressed in pre-Sertoli cells, somatic cells that surround primordial germ cells (PGCs), in the early gonadal primordium before any morphological sex differences are seen (Matsuda et al. 2002; Kobayashi et al. 2004). In the medaka, the first indication of morphological sex differences is a difference in the number of germ cells between the sexes at hatching (Satoh and Egami 1972; Quirk and Hamilton 1973; Hamaguchi 1982; Kobayashi et al. 2004). It is considered that one of the functions of DMY is to act as a factor that regulates the proliferation of PGCs via Sertoli cells in a sex-specific manner and controls testicular differentiation (Kobayashi et al. 2004).

In humans, mutations in the SRY gene result in XY sex reversal and pure gonadal dysgenesis (Jager et al. 1990). However, mutations in the SRY gene itself are considered to account for only 10–15% of 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis cases, and the majority of the remaining cases may have mutation(s) in SRY regulatory elements or other genes involved in the sex differentiation pathway (Cameron and Sinclair 1997). A number of genes have been identified as having roles in the sexual development pathway through analyses of human sexual anomaly cases and/or functional studies in mice (Koopman 2001).

Sex-reversal mutants in medaka are also useful for revealing the molecular function of DMY and identifying other genes involved in sex determination and differentiation. Analyses of such mutants may lead to further understanding of the molecular mechanisms of sex differentiation. In the present study, we identified two types of DMY mutants derived from wild populations of medaka. The first type is composed of loss-of-function mutants that contain mutations at the 3′ region of the DM domain, suggesting that the 3′ region of the DM domain is required for the normal function of DMY, male sex determination, and development. The second type is composed of reduced DMY expression mutants that have lower levels of DMY transcripts and contain a number of germ cells, including oocytes, at hatching. Taken together, these results suggest that early testis development requires DMY expression above a threshold level and support the hypothesis that DMY acts as a factor regulating PGC proliferation via Sertoli cells during early gonadal differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fish and mating schemes:

In our previous study, we surveyed 2274 wild-caught fish from 40 localities throughout Japan and 730 fish from 69 wild stocks from Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan and identified 23 XY females from 11 localities (Shinomiya et al. 2004). Genetic analyses revealed that the XY females from 8 localities produced all female XYm (Ym, Y chromosome derived from an XY female) progeny, while those from 3 localities yielded both male and female XYm progeny (Table 1), suggesting that all these wild XY females had Y-linked gene mutations. In this study, we established mutant strains from these XY female mutants. The XY females from northern populations were mated with XY males of an inbred strain Hd-rR (Hyodo-Taguchi 1996) and the XY females from southern populations were mated with a congenic strain Hd-rR.YHNI (Matsuda et al. 1998). The F1 progeny from each pair were grown and their genotypes were determined, since the DMY gene of the northern population, including the HNI inbred strain, contains 21 nucleotide deletions in intron 2 compared to the southern population, including the Hd-rR strain (Shinomiya et al. 2004). When an XY female produced all female F1 XYm progeny, an F1 XYm female was mated with an F1 YYm male to produce F2 YmYm females. Next, an F2 YmYm female was mated with an F2 YYm male to establish mutant strains producing YmYm females and YYm males in later generations. When an XY female produced male and female F1 XYm progeny, an F1 XYm female was mated with an F1 YYm male to produce F2 YmYm males. Next, an F2 YmYm male was mated with an F2 XYm female to establish mutant strains producing XYm males and females and YmYm males in later generations. These mutant strains were used for RT–PCR and histological analyses.

TABLE 1.

List of XY sex-reversal mutants from wild populations of medaka

| Collection site | N | Phenotypic sex of XYm F1 | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aomori, Aomori Prefecture | 2 | All female | N |

| Aizu-wakamatsu, Fukushima Prefecture | 2 | Males and females | N |

| Aizu-bange, Fukushima Prefecture | 1 | All female | N |

| Shirone, Niigata Prefecture | 2 | Males and females | N |

| Kurobe, Toyama Prefecture | 6 | All female | N |

| Suzu, Ishikawa Prefecture | 1 | All female | N |

| Awara, Fukui Prefecture | 1 | All female | N |

| Kesen-numa, Miyagi Prefecture | 2 | Males and females | S |

| Saigo, Shimane Prefecture | 3 | All female | S |

| Aki, Kochi Prefecture | 1 | All female | S |

| Oura, Kagoshima Prefecture | 2 | All female | S |

From Shinomiya et al. (2004). N, number of XY females; Ym, Y chromosome derived from an XY female; N, northern Population; S, southern Population (Sakaizumi et al. 1983; Sakaizumi 1986).

PCR and direct sequencing:

To screen for mutations in the amino acid coding sequence of DMY, exons 2–6 of DMY were PCR-amplified from caudal fin clip DNA using the following primer sets: exon 2: PG17ex2.1, 5′-GGA GTC ACG TGA CCC TCT TTC TTG GG-3′ and PG17ex2.2, 5′-TTT CGG GTG AAC TCA CAT GGT TGT CG-3′; exon 3: PG17ex3.1, 5′-GCA ACA GAG AGT TGG ATT TAC GTC TCA-3′ and PG17ex3.2, 5′-CTT TTG ACT TCA GTT TGA CAC ATC AAT G-3′; exon 4: PG17ex4.1, 5′-CTC AGG TTT GAC TTG GAT GCT GAC CTG A-3′ and PG17ex4.2, 5′-CAA ACC AGG CCA TGA CCA TTC CGA-3′; exon 5: PG17ex5.1, 5′-CCG ATT CTA GCG GAT GAT GCC ACC-3′ and PG17ex5.2, 5′-GGG AGC CAA AAA TGC GCC ACA TAA-3′; and exon 6: PG17ex6.1, 5′-GTC ATT AAC ACA ACG CAC AAC AAC TT-3′ and PG17ex6.2, 5′-AAA AAC CAG AAG ACC CGA GAG GAA G-3′ (Figure 1A). The PCR products were sequenced directly in an ABI Prism 310 automated sequencer.

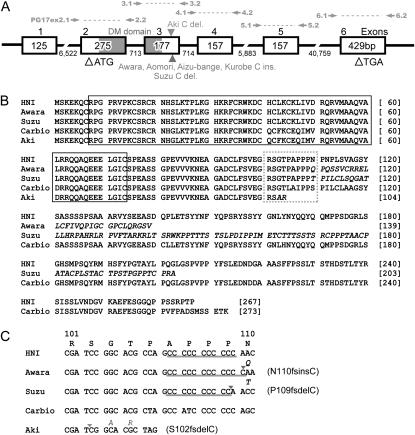

Figure 1.—

Structure and sequences of DMY. (A) DMY structure of the Hd-rR.YHNI congenic strain. Open boxes, shaded boxes, and the horizontal line indicate exons, the DM domain, and introns, respectively. Open arrowheads indicate the translation start site ATG and stop site TGA. Numbers represent the nucleotide sequence length (bp). Solid arrowheads indicate the positions of insertions or deletions. Solid arrows indicate the primer positions. (B) Amino acid sequences of the Hd-rR.YHNI congenic strain, Carbio strain from the southern population, and wild-derived sex-reversal mutants. The DM domain is boxed. Italicized letters indicate missense coding. (C) Nucleotide sequences of Hd-rR.YHNI, Carbio, and wild-derived sex-reversal mutants at the polyC tract in exon 3 depicted by the dotted box in B. The polyC tract specific to the northern population is underlined. Solid arrowheads indicate the positions of nucleotide insertions or deletions. The Suzu XY female has a cytosine deletion at amino acid 109 (designated P109fsdelC), the Awara XY female has a cytosine insertion at amino acid 110 (designated N110fsinsC), and the Aki XY female has a cytosine deletion at amino acid 102 (designated S102fsdelC), each of which results in a frameshift and premature termination.

RNA extraction and densitometric semiquantitative RT–PCR:

Total RNA was extracted from embryos or fry at 9.5 days after fertilization in Kesen-numa G2, Shirone G2, Aizu-Wakamatsu G2, and Oura G4 generations using an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN) and subjected to RT–PCR using a OneStep RT–PCR kit (QIAGEN). Aliquots (20 ng) of the total RNA samples were used as templates in 25-μl reaction volumes. The PCR conditions were: 30 min at 55°; 15 min at 95°; cycles of 20 sec at 96°, 30 sec at 55°, and 60 sec at 72°; and 5 min at 72°. The number of cycles for each gene was adjusted to be within the linear range of amplification, specifically 36 cycles for DMY and 24 cycles for β-actin. The primers for DMY (DMYspe, 5′-TGC CGG AAC CAC AGC TTG AAG ACC-3′ and 48U, 5′-GGC TGG TAG AAG TTG TAG TAG GAG GTT T-3′) amplified a 404-bp DNA fragment. The primers for β-actin (3b, 5′-CMG TCA GGA TCT TCA TSA GG-3′ and 4, 5′-CAC ACC TTC TAC AAT GAG CTG A-3′) amplified a 322-bp DNA fragment. Aliquots of 8 and 4 μl of the DMY and β-actin RT–PCR products, respectively, were electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer and stained with ethidium bromide. The gels were visualized by UV transillumination and photographed with a Geldoc 2000 (Bio-Rad). The optical density of each band was quantified by densitometry using Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad) and represented as the ratio of DMY mRNA to β-actin mRNA in arbitrary units. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for statistically significant differences among XYHNI, XYHd-rR, and XY sex-reversal mutants, and the Games/Howell post hoc test for multiple comparisons was applied.

Histological analysis in early gonadal development:

The fry of the Kesen-numa G2 and Oura G4 generations at 0 and 10 days after hatching (dah) were cut to separate the head and body. The body portions were fixed in Bouin's fixative solution overnight and then embedded in paraffin. The heads were used to determine the genotype. Serial cross-sections (5 μm thick) of the body portions were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Germ cells were counted in each fry at 0 dah. After the cell counting, the mean number and SE were calculated for the Oura G4 generation and the differences between YwOurYwOur and YHNIYwOur individuals were evaluated statistically by paired t-tests. Gonadal sex differentiation at 10 dah was examined for the presence or absence of diplotene oocytes.

RESULTS

Mutations in the DMY amino acid coding sequence:

To identify mutations in the DMY amino acid coding sequence, we sequenced exons 2–6 of DMY (Figure 1A) in 23 XY sex-reversed females from 11 localities. Four types of mutations were identified in 15 XY females from 7 localities. One Awara (Matsuda et al. 2002), 2 Aomori, 1 Aizu-Bange, and 6 Kurobe XY females contained a C insertion in a polyC tract specific to the northern population in exon 3 (Figure 1, A and C), which caused a frameshift from residue 110 (designated N110fsinsC) and resulted in premature termination at residue 139 (Figure 1B). An XY female from Suzu contained a C deletion in the same polyC tract in exon 3 (Figure 1, A and C), which caused a frameshift from residue 109 (designated 109fsdelC) and resulted in premature termination at residue 203 (Figure 1B). An XY female from Aki contained a C deletion in another site in exon 3 (Figure 1, A and C), which caused a frameshift from residue 102 (designated S102fsdelC) and resulted in premature termination at residue 104 (Figure 1, B and C). Three XY females from Saigo had normal DMY exons 2–5, but PCR for exon 6 (using primers PG17ex6.1 and PG17ex6.2; Figure 1A) and 3′-RACE using RNA extracted from G2 YwSaiYwSai (YwSai, Y chromosome derived from a Saigo XY female) fry at 0 dah did not produce any amplified bands (data not shown), suggesting that the DMY gene of these Saigo XY females may contain a large insertion or deletion in intron 5 and/or exon 6 and have no polyadenylation signal. The XY females from Awara, Aomori, Aizu-Bange, Kurobe, Suzu, Aki, and Saigo that contained mutations in the amino acid coding sequence produced all female XYm progeny in the G1 generation (Table 1), indicating their mutant DMY genes were nonfunctional.

Patterns of inheritance for sex reversal in Oura and Kesen-numa medaka:

The XY females from Shirone, Aizu-Wakamatsu, Kesen-numa, and Oura produced sex-reversed XYm female progeny in the G1 generation, although the amino acid coding sequence of DMY was normal. To investigate the patterns of inheritance for sex reversal in more detail, we performed further genetic analyses for the Oura and Kesen-numa XY females.

For Oura, G1 XYwOur (YwOur, Y chromosome derived from an Oura XY female) progeny produced from a mating between the XY female and an Hd-rR.YHNI male developed as all female (Figure 2A), suggesting that YwOur had lost the male-determining function. Since YHNIYwOur did not appear in the G1 generation, another G1 XYwOur female was mated with the Hd-rR.YHNI male. All 33 G3 YwOurYwOur progeny produced from a mating between a G2 XYwOur female and a G2 YHNIYwOur male developed as female (Figure 2A). This result confirmed that YwOur has lost the male-determining function.

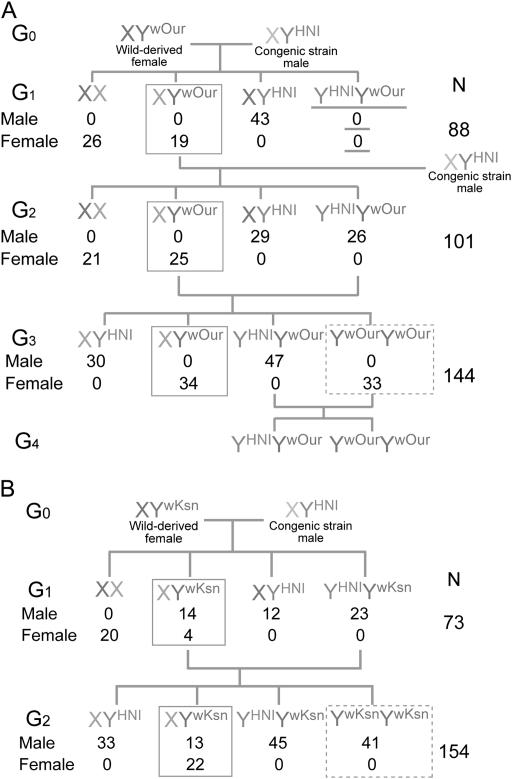

Figure 2.—

Schemes illustrating genetic crosses for XY females from Oura and Kesen-numa. (A) The Oura XY female produced all female XYwOur progeny in the G1, G2, and G3 generations (boxes with a solid line). Since YHNIYwOur did not appear in the G1 generation (underlined), a G1 XYwOur female was mated with the Hd-rR.YHNI male again. All 33 YwOurYwOur individuals developed into females in the G3 generation (dotted box). (B) The Kesen-numa XY female produced male and female XYwKsn progeny in the G1 and G2 generations (boxes with a solid line). All 41 YwKsnYwKsn individuals developed into males in the G2 generation (dotted box). YHNIYwOur and YHNIYwKsn individuals developed into normal males in adulthood.

For Kesen-numa, G1 XYwKsn (YwKsn, Y chromosome derived from a Kesen-numa XY female) progeny produced from a mating between the XY female and an Hd-rR.YHNI male were either male or female, similar to the case for the Shirone XY female (Matsuda et al. 2002). Interestingly, we observed only 4 females among 18 XYwKsn in the G1 generation, while 22 XYwKsn females were observed among 35 XYwKsn in the G2 generation (Figure 2B). Conversely, all 41 G2 YwKsnYwKsn produced from a mating between a G1 XYwKsn female and a G1 YHNIYwKsn male developed as male (Figure 2B), suggesting that two YwKsn chromosomes are sufficient for male determination and development. YHNIYwKsn and YHNIYwOur, which contained normal Y chromosomes from the Hd-rR.YHNI congenic strain, developed into normal males in adulthood.

Mutants with reduced DMY expression at the sex-determining period:

The XY females from Shirone had reduced or faint DMY expression at 0 dah (Matsuda et al. 2002). To define the relationship between sex reversal and the DMY expression level, we detected DMY transcripts at 0 dah for Kesen-numa G2, Aizu-Wakamatsu G2, Shirone G2, and Oura G4 generations that produced sex-reversed females, despite a normal amino acid coding sequence of DMY. To measure the DMY expression levels semiquantitatively, we performed densitometric RT–PCR. The mRNA levels of DMY were calibrated by those of β-actin (Figure 3A) and are shown as the ratios of DMY mRNA to β-actin mRNA in arbitrary units (Figure 3B). Statistical analyses using the Games/Howell post hoc test revealed that the DMY mRNA level was significantly lower in YwKsnYwKsn than in males of XYHd-rR and XYHNI, although YwKsnYwKsn developed as all male in adulthood. The statistical analyses further revealed that the DMY mRNA levels were significantly lower in XYwKsn, XYwSrn (YwSrn, Y chromosome derived from a Shirone XY female), and XYwWkm (YwWkm, Y chromosome derived from an Aizu-Wakamatsu XY female), which developed as male or female in adulthood, as well as in YwOurYwOur, which developed as all female in adulthood, than in males of XYHd-rR, XYHNI, and YwKsnYwKsn (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.—

Expression levels of the DMY transcript at 0 dah in XYHNI, XYHd-rR, and XY sex-reversal mutants. (A) Ethidium bromide-staining of the DMY transcripts following gel electrophoresis. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Semiquantitative densitometric analysis of the DMY transcripts. Columns show the ratio of DMY mRNA to β-actin mRNA in arbitrary units. The ratios are given as the mean ± standard error of six independent assays. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between the mean values: *P < 0.05 compared with XYHNI and XYHd-rR; **P < 0.05 compared with XYHNI, XYHd-rR, and YwKsnYwKsn.

Early gonadal development of mutants with reduced DMY expression:

We carried out histological observations for the Oura G4 and Kesen-numa G2 generations at 0 and 10 dah to reveal the early gonadal development of the mutants with reduced DMY expression. It is well known that the number of germ cells in many non-mammalian females is greater than that in males around the time of morphological sex differentiation (Van Limborgh 1975; Zust and Dixon 1977; Nakamura et al. 1998). Thereafter, the germ cells in females continue to proliferate and then enter into meiosis, while the male germ cells arrest in mitosis. We counted the number of germ cells at 0 dah (Figure 4), which represents the time of the initial appearance of morphological sex differences in medaka (Satoh and Egami 1972; Quirk and Hamilton,1973; Hamaguchi 1982). Around hatching, germ cells in XX individuals outnumber those in XY individuals (Hamaguchi 1982; Kobayashi et al. 2004) and subsequently germ cells enter mitotic arrest in XY fry, whereas they go into meiosis in XX fry after hatching (Satoh and Egami 1972). Further, we examined the early gonadal development according to the presence or absence of diplotene oocytes at 10 dah (Table 2; Figure 5). In this period, the female germ cells are recognizable as oocytes from histological observations since the fry in putative male contain no germ cells in the meiotic prophase, while those in putative female contain germ cells both in mitosis and in the meiotic prophase (Satoh and Egami 1972).

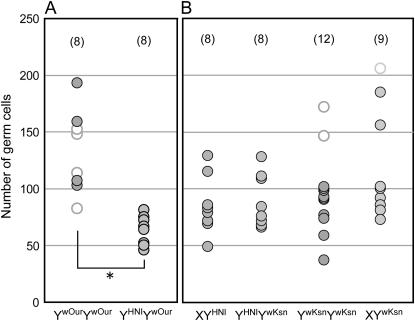

Figure 4.—

Germ-cell numbers of mutants with reduced DMY expression at 0 dah in the Oura G4 (A) and Kesen-numa G2 (B) generations. YHNI indicates the Y chromosome derived from the Hd-rR.YHNI congenic strain with intact DMY. Open circles indicate gonads containing oocytes. Solid circles indicate gonads without oocytes. The numbers of samples are shown in parentheses. There is a significant difference between the germ-cell numbers for YwOurYwOur and YHNIYwOur (*P < 0.01).

TABLE 2.

Gonadal development at 10 dah in mutant lines

| No. of fry

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant line and generation | Genotype | No. of fry examined | With DO | Without DO |

| Oura G4 | YwOurYwOur | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| YwOurYHNI | 8 | 0 | 8 | |

| Kesen-numa G2 | XYHNI | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| XYwKsn | 16 | 14 | 2 | |

| YwKsnYHNI | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| YwKsnYwKsn | 8 | 0 | 8 | |

DO, diplotene oocyte; YwOur, Y chromosome derived from an Oura XY female; YHNI, Y chromosome derived from an Hd-rR.YHNI congenic strain male; YwKsn, Y chromosome from a Kesen-numa XY female.

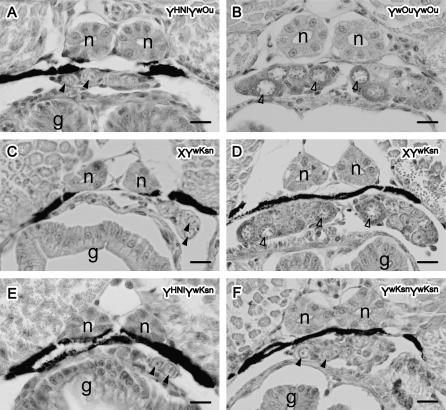

Figure 5.—

Gonadal sex differentiation in the Kesen-numa and Oura mutant strains at 10 dah. The gonads of YwOurYwOur (B) and most XYwKsn (D) developed as female, while the gonads of YHNIYwOur (A), the remaining XYwKsn (C), YHNIYwKsn (E), and YwKsnYwKsn (F) developed as male. Solid arrowheads indicate germ cells. Open arrowheads indicate diplotene stage oocytes. n, pronephric duct; g, gut. Bars, 10 μm.

For Oura, YwOurYwOur, with the lowest DMY expression levels among the tested mutants, contained a number of germ cells, including oocytes, at 0 dah (Figure 4A), similar to normal XX females, and all eight YwOurYwOur had diplotene oocytes at 10 dah (Table 2; Figure 5B). These results suggest that YwOurYwOur develops as female in the same manner as normal XX females. YHNIYwOur, with a normal Y chromosome from the Hd-rR.YHNI congenic strain, had a significantly lower germ-cell number at 0 dah than YwOurYwOur (Figure 4A), and no oocytes were observed at either 0 or 10 dah (Table 2; Figure 5A). These results suggest that YHNIYwOur develops as male in the same manner as normal XY males.

For Kesen-numa, YwKsnYwKsn and XYwKsn, with reduced DMY expression, had a number of germ cells, including oocytes, at 0 dah (Figure 4B). However, at 10 dah all eight YwKsnYwKsn had a small number of germ cells and no diplotene oocytes (Table 2; Figure 5F), similar to normal males. These results suggest that some of the YwKsnYwKsn germ cells proliferate like those in normal females at hatching, but the mutants develop as male by 10 dah. Conversely, 14 of 16 XYwKsn had diplotene oocytes at 10 dah (Table 2; Figure 5D) and the remaining 2 XYwKsn had a small number of germ cells and no diplotene oocytes at 10 dah (Table 2; Figure 5C). These results are consistent with the observations that XYwKsn were either male or female in adulthood and that the number of females was greater than that of males in the G2 generation. Some XYwKsn individuals would probably develop as females in the same manner as normal females. XYHNI and YHNIYwKsn, with a normal Y chromosome from the Hd-rR.YHNI congenic strain, contained no diplotene oocytes at either 0 or 10 dah (Table 2; Figure 5E), indicating that these individuals would develop as normal males.

DISCUSSION

Characteristics of the DMY mutations:

The results of this study indicate that all XY sex-reversal mutants discovered among wild populations of medaka are associated with defective DMY and can be classified into two types. One type contains mutations in the amino acid coding sequence of DMY (Awara, Aomori, Aizu-Bange, Kurobe, Suzu, Aki, and Saigo), while the other type has a normal coding sequence but reduced DMY expression at 0 dah (Shirone, Aizu-Wakamatsu, Kesen-numa, and Oura).

In humans, mutations in SRY are associated with male-to-female sex reversal and a number of mutations have been identified within the SRY gene open reading frame (Shahid et al. 2004). Although nonsense mutations are scattered throughout the SRY gene, missense mutations tend to cluster in the central region of the gene, which encodes the high-mobility group (HMG) domain (Harley et al. 2003). In total, 43 of 53 missense mutations identified in the SRY gene open reading frame are located in the HMG domain (Shahid et al. 2004), strongly suggesting that the DNA-binding motif is essential in vivo. Conversely, only 10 mutations that lie outside the HMG domain have been detected. Among these, 7 are located in the 5′ region and 3 are located in the 3′ region of the HMG domain and all have different effects on the patient phenotype (Shahid et al. 2004). It is hypothesized that the region outside the HMG domain may be required to stabilize protein binding and/or to generate specificity by helping to discriminate between protein partners (Wilson and Koopman 2002).

The results of the present study demonstrate the occurrence of three types of DMY frameshift mutations. N110fsinsC was found in four populations (Awara, Aomori, Aizu-Bange, and Kurobe), while P109fsdelC was found in Suzu and S102fsdelC was found in Aki. The N110fsinsC and P109fsdelC frameshift mutations are present in the same polyC tract in exon 3, which is specific to the northern population. These mutations may have occurred independently in different populations, implying that this region is a mutational hot spot in the DMY gene, similar to the case for the human transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)-1a, which contains a polyC tract in exon 4 (Kaisaki et al.1997). The finding that all XYm containing each of N110fsinsC, P109fsdelC, and S102fsdelC in DMY developed as female in adulthood indicates that the mutated DMY genes do not have the male-determining function, although they contain the intact DM domain. Taken together, these results suggest that the 3′ region of the DM domain is indispensable for fulfilling the male-determining function of DMY.

XY sex reversal is associated with reduced DMY expression:

In mice, XY sex reversal is associated with two types of mutation that appear to exert their effects by suppressing the Sry expression level. First, deletion of repeat sequences at some distance proximal to Sry on the mouse Y short arm results in reduced expression and sex reversal (Capel et al. 1993). Second, the sex reversal observed when crossing a Mus mus musculus strain Poschiavinus Y chromosome (YPOS) onto a M. m. domesticus background (in particular C57BL6) (Eicher et al. 1982) has been attributed to a reduced Sry expression level from YPOS. Using a semiquantitative RT–PCR assay, Nagamine et al. (1999) showed that the levels of Sry expression from different mouse Y chromosomes are correlated with the degree of sex reversal they cause on an M. m. domesticus background. It appears that a critical threshold level must be achieved by a certain stage of genital ridge development for the supporting cell population to be pushed toward Sertoli cell differentiation.

In medaka, DMY expression first appears just before hatching and morphological sex differences are seen, whereas the expression of autosomal gene DMRT1 first occurs at 20–30 dah (Kobayashi et al. 2004). The present results demonstrate that the DMY expression levels at 0 dah in XYwKsn, XYwSrn, XYwWk, and YwOurYwOu, which produced sex-reversed females, are significantly reduced to less than half the levels in males of XYHNI and XYHd-rR. These results suggest that an underlying cause of XY sex reversal is a reduced level of DMY mRNA during a critical period of sex determination. It is interesting to note that YwKsnYwKsn developed as all male in adulthood, although their DMY mRNA level was significantly lower than that in XYHNI and XYHd-rR. Therefore, we consider that the certain threshold level of DMY mRNA required for male determination at 0 dah lies between the YwKsnYwKsn and XYwKsn mRNA levels.

Lower levels of DMY transcripts lead the gonads to develop as phonotypic females:

In mice, Sry is expressed in pre-Sertoli cells (Albrecht and Eicher 2001) and required for male determination by means of promotion of Sertoli cell differentiation (Swain and Lovell-Badge 1999). In medaka, DMY is expressed in the pre-Sertoli cells (Matsuda et al. 2002; Kobayashi et al. 2004) and assumed to act as a factor that induces the development of pre-Sertoli cells into Sertoli cells in XY gonads, which is involved in the regulation of PGC proliferation as well as construction of the testicular tissue architecture (Matsuda 2005).

In the present study, we demonstrated reduced DMY expression at 0 dah in sex-reversed mutant strains. There are two possible causes for this reduced DMY expression: (1) the number of DMY-expressing cells is normal but the level of DMY transcription per cell is severely reduced or (2) the number of DMY-expressing cells is significantly reduced but the level of DMY transcription per cell is normal. Either of these possibilities could severely affect the development of pre-Sertoli cells into Sertoli cells. It is interesting to note that some XX recipient and XY donor chimeras of medaka develop into males that have only XX germ cells (Shinomiya et al. 2002). These results suggest that the XY somatic donor cells, the minor component in these chimeras, could induce sex reversal of the XX germ cells and the XX somatic cells. From these results, we infer that the latter possibility is unlikely to cause sex reversal, and it is reasonable to assume that the former possibility is the cause of the reduced DMY expression.

Our finding that YwOurYwOur develops as female in the same manner as normal XX females indicates that a low DMY mRNA level below the threshold level may lead to failure of DMY-positive cells to further differentiate into Sertoli cells. Since Sertoli cells are necessary for regulating PGC proliferation, lower levels of DMY transcripts lead to gonad development as phenotypic females. In contrast, the fact that YwKsnYwKsn develops as all male by 10 dah suggests that a DMY mRNA level above the threshold level at the sex-determining period is necessary for pre-Sertoli cells to undergo further differentiation. However, some YwKsnYwKsn individuals contain a number of germ cells, including oocytes, at 0 dah. This result implies that slightly reduced DMY expression may lead to a reduction in pre-Sertoli cell development into Sertoli cells. Moreover, some XYwKsn develop as females and the remainder as males by 10 dah, although the DMY mRNA levels at 0 dah did not differ significantly among the six tested XYwKsn individuals (data not shown). The increase in the sex-reversal ratio seen in Kesen-numa G2 suggests the possibility that autosomal loci are related to the sex reversal in addition to a reduced DMY expression level, similar to the case for the tda genes in mice (Eicher et al. 1996).

The mutants with reduced DMY expression may contain regulatory mutations in the flanking region of DMY. Future experiments will be focused on identifying the DMY expression control elements. These mutants may prove valuable for identifying DMY regulatory elements that are involved in transcriptional control.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yoshitaka Nagahama (Laboratory of Reproductive Biology, National Institute of Basic Biology) for his generosity in letting H.O. use his facility. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (11236205 to M.S.).

References

- Aida, T., 1921. On the inheritance of color in a fresh-water fish, Aplocheilus latipes Temmick and Schlegel, with special reference to sex-linked inheritance. Genetics 6: 554–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, K. H., and E. M. Eicher, 2001. Evidence that Sry is expressed in pre-Sertoli cells and Sertoli and granulosa cells have a common precursor. Dev. Biol. 240: 92–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, F. J., and A. H. Sinclair, 1997. Mutations in SRY and SOX9: testis-determining genes. Hum. Mutat. 9: 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capel, B., C. Rasberry, J. Dyson, C. E. Bishop, E. Simpson et al., 1993. Deletion of Y chromosome sequences located outside the testis determining region can cause XY female sex reversal. Nat. Genet. 5: 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher, E. M., L. L. Washburn, J. B. Whitney, III and K. E. Morrow, 1982. Mus poschiavinus Y chromosome in the C57BL/6J murine genome causes sex reversal. Science 217: 535–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher, E. M., L. L. Washburn, N. J. Schork, B. K. Lee, E. P. Shown et al., 1996. Sex-determining genes on mouse autosomes identified by linkage analysis of C57BL/6J-YPOS sex reversal. Nat. Genet. 14: 206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubbay, J., J. Collignon, P. Koopman, B. Capel, A. Economou et al., 1990. A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature 346: 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi, S., 1982. A light- and electron-microscopic study on the migration of primordial germ cells in the teleost, Oryzias latipes. Cell Tissue Res. 227: 139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley, V. R., M. J. Clarkson and A. Argentaro, 2003. The molecular action and regulation of the testis-determining factors, SRY (sex-determining region on the Y chromosome) and SOX9 [SRY-related high-mobility group (HMG) box 9]. Endocr. Rev. 24: 466–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyodo-taguchi, Y., 1996. Inbred strains of the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Fish Biol. J. Medaka 8: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, R. J., M. Anvret, K. Hall and G. Scherer, 1990. A human XY female with a frame shift mutation in the candidate testis-determining gene SRY. Nature 348: 452–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaisaki, P. J., S. Menzel, T. Lindner, N. Oda, I. Rjasanowski et al., 1997. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene in MODY and early-onset NIDDM: evidence for a mutational hotspot in exon 4. Diabetes 46: 528–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T., M. Matsuda, H. Kajiura-Kobayashi, A. Suzuki, N. Saito et al., 2004. Two DM domain genes, DMY and DMRT1, involved in testicular differentiation and development in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Dev. Dyn. 231: 518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, M., I. Nanda, U. Hornung, M. Schmid and M. Schartl, 2004. Evolutionary origin of the medaka Y chromosome. Curr. Biol. 14: 1664–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, P., 2001. The genetics and biology of vertebrate sex determination. Cell 105: 843–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, P., J. Gubbay, N. Vivian, P. Goodfellow and R. Lovell-Badge, 1991. Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature 351: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell-Badge, R., C. Canning and R. Sekido, 2002. Sex-determining genes in mice: building pathways. Novartis Found. Symp. 244: 4–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, M., 2005. Sex determination in the teleost medaka, oryzias latipes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39: 293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, M., C. Matsuda, S. Hamaguchi and M. Sakaizumi, 1998. Identification of the sex chromosomes of the medaka, Oryzias latipes, by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytogenet. Cell. Genet. 82: 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, M., Y. Nagahama, A. Shinomiya, T. Sato, C. Matsuda et al., 2002. DMY is a Y-specific DM-domain gene required for male development in the medaka fish. Nature 417: 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine, C. M., K. Morohashi, C. Carlisle and D. K. Chang, 1999. Sex reversal caused by Mus musculus domesticus Y chromosomes linked to variant expression of the testis-determining gene Sry. Dev. Biol. 216: 182–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, M., T. Kobayashi, X.-T. Chang and Y. Nagahama, 1998. Gonadal sex differentiation in teleost fish. J. Exp. Zool. 281: 362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, I., M. Kondo, U. Hornung, S. Asakawa, C. Winkler et al., 2002. A duplicated copy of DMRT1 in the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome of the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 11778–11783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk, J. G., and J. B. Hamilton, 1973. Number of germ cells in known male and known female genotypes of vertebrate embryos (Oryzias latipes). Science 180: 963–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C. S., C. E. Shamu, M. M. Shen, K. J. Seifert, B. Hirsch et al., 1998. Evidence for evolutionary conservation of sex-determining genes. Nature 391: 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaizumi, M., 1986. Genetic divergence in wild populations of the medaka Oryzias latipes (Pisces: Oryziatidae) from Japan and China. Genetica 69: 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaizumi, M., K. Moriwaki and N. Egami, 1983. Allozymic variation and regional differentiation in wild population of the fish Oryzias latipes. Copeia 2: 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, N., and N. Egami, 1972. Sex differentiation of germ cells in the teleost, Oryzias latipes, during normal embryonic development. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 28: 385–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M., V. S. Dhillion, N. Jain, S. Hedau, S. Diwakar et al., 2004. Two new novel point mutations localized upstream and downstream of the HMG box region of the SRY gene in three Indian 46,XY females with sex reversal and gonadal tumour formation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 10: 521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomiya, A., N. Shibata, M. Sakaizumi and S. Hamaguchi, 2002. Sex reversal of genetic females (XX) induced by the transplantation of XY somatic cells in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46: 711–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomiya, A., H. Otake, K. Togashi, S. Hamaguchi and M. Sakaizumi, 2004. Field survey of sex-reversals in the medaka, Oryzias latipes: genotypic sexing of wild populations. Zool. Sci. 21: 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, A. H., P. Berta, M. S. Palmer, J. R. Hawkins, B. L. Griffiths et al., 1990. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature 346: 240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain, A., and R. Lovell-Badge, 1999. Mammalian sex determination: a molecular drama. Genes Dev. 13: 755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Limborgh, J., 1975. Origin and destination of the median germ cells in late somite stage and early post-somite stage duck embryos. Acta Morphol. Neerl. Scand. 13: 171–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M., and P. Koopman, 2002. Matching SOX: partner proteins and co-factors of the SOX family of transcriptional regulators. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zust, B., and K.E. Dixon, 1977. Event in the germ cell lineage after entry of the primordial germ cells into the genital ridges in normal and u.v.-irradiated Xenopus laevis. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 41: 3–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]