Abstract

Histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes have been linked to activation of transcription. Reptin is a subunit of different chromatin-remodeling complexes, including the TIP60 HAT complex. In Drosophila, Reptin also copurifies with the Polycomb group (PcG) complex PRC1, which maintains genes in a transcriptionally silent state. We demonstrate genetic interactions between reptin mutant flies and PcG mutants, resulting in misexpression of the homeotic gene Scr. Genetic interactions are not restricted to PRC1 components, but are also observed with another PcG gene. In reptin homozygous mutant cells, a Polycomb response-element-linked reporter gene is derepressed, whereas endogenous homeotic gene expression is not. Furthermore, reptin mutants suppress position-effect variegation (PEV), a phenomenon resulting from spreading of heterochromatin. These features are shared with three other components of TIP60 complexes, namely Enhancer of Polycomb, Domino, and dMRG15. We conclude that Drosophila Reptin participates in epigenetic processes leading to a repressive chromatin state as part of the fly TIP60 HAT complex rather than through the PRC1 complex. This shows that the TIP60 complex can promote the generation of silent chromatin.

A fundamental regulatory step in transcription and other DNA-dependent processes in eukaryotes is the control of chromatin structure, which regulates access of proteins to DNA. Histone acetylation and the protein complexes that mediate this modification have been linked to activation of transcription (Struhl 1998). It is believed that lysine acetylation of histone N termini results in less compact chromatin by neutralizing the positive charge of histones and that the acetyl groups are recognized by regulatory proteins that promote transcription (Workman and Kingston 1998; Strahl and Allis 2000). However, it is becoming clear that histone acetyltransferases (HATs) can have functions other than facilitating transcription (Carrozza et al. 2003). For example, the TIP60 HAT complex has been implicated in DNA repair in yeast, flies, and mammals (Ikura et al. 2000; Bird et al. 2002; Kusch et al. 2004). We have investigated the role of Drosophila Reptin and other TIP60 components in chromatin regulation in vivo.

The Reptin protein, also known as TIP48, TIP49b, or RUVBL2, is related to bacterial RuvB, an ATP-dependent DNA helicase that promotes branch migration in Holliday junctions (Kanemaki et al. 1999). Reptin, and the related Pontin (TIP49, TIP49a, or RUVBL1) protein, possess intrinsic ATPase and helicase activities and can heterodimerize (Kanemaki et al. 1999; Makino et al. 1999). In yeast, both Reptin and Pontin are part of the INO80 chromatin-remodeling complex (Shen et al. 2000), as well as the Swr1 complex that can exchange histone H2A with the variant histone H2A.Z (Krogan et al. 2003; Kobor et al. 2004; Mizuguchi et al. 2004). Reptin and Pontin appear to play antagonistic roles in development by regulating Wnt signaling (Bauer et al. 2000) and heart growth in zebrafish embryos (Rottbauer et al. 2002). Mammalian Reptin and Pontin are present in TIP60 HAT complexes, which are involved in induction of apoptosis in response to DNA damage and which interact with the c-Myc protein to promote its oncogenic activity (Ikura et al. 2000; Wood et al. 2000; Fuchs et al. 2001; Cai et al. 2003; Frank et al. 2003; Doyon et al. 2004).

TIP60 is a HAT of the MYST family (Utley and Cote 2003). The homologous yeast protein Esa1 is the catalytic subunit of the nucleosome acetyltransferase of H4 (NuA4) complex, which acetylates lysines in histone H4 and H2A (Doyon and Cote 2004). In Drosophila, the TIP60 complex acetylates the phosphorylated variant histone H2Av after DNA double-strand breaks and exchanges it with unmodified H2Av (Kusch et al. 2004). The composition of TIP60 and NuA4 complexes has recently been determined (Doyon and Cote 2004). TIP60 (yeast Esa1), ING3 (Yng2), and Enhancer of Polycomb (EPC1, yeast Epl1) form a core complex that is sufficient for acetylation of histones in nucleosomes (Boudreault et al. 2003; Doyon et al. 2004). Mammalian and Drosophila TIP60 complexes contain four subunits not present in yeast NuA4 (Doyon et al. 2004; Kusch et al. 2004): Brd8, Reptin, Pontin, and Domino (also known as p400), the homolog of yeast Swr1.

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are evolutionarily conserved chromatin regulators that maintain appropriate expression patterns of developmental control genes, such as the Hox genes (Ringrose and Paro 2004). PcG proteins are generally repressors that maintain the off state of genes and exist in at least two distinct protein complexes. The Esc–E(z) complex is a histone methyltransferase that includes the catalytic subunit Enhancer of zeste [E(z)], as well as the extra sex combs (esc) and suppressor of zeste 12 [Su(z)12] subunits (Birve et al. 2001; Cao et al. 2002; Czermin et al. 2002; Kuzmichev et al. 2002; Muller et al. 2002). Another complex purified from Drosophila embryos, Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) has a mass of >1 MDa (Shao et al. 1999). In addition to genetically identified PcG proteins, it includes TFIID subunits, the Reptin protein, and other polypeptides (Saurin et al. 2001). The PRC1 complex can block chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF complex in vitro (Levine et al. 2004). A core PRC1 complex consisting of Polycomb (Pc), Posterior sex combs (Psc), Polyhomeotic (Ph), and dRING1/Sex combs extra (Sce) is sufficient for the in vitro activities of PRC1 (Levine et al. 2004). Recently, it was shown that dRing1/Sce as well as its mammalian orthologs are E3 ubiquitin ligases that monoubiquitylate histone H2A (de Napoles et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2004).

Here, we investigate the role of Drosophila Reptin in chromatin regulation. We show that it interacts genetically with PcG gene products and suppresses position-effect variegation (PEV), properties shared by other Drosophila TIP60 complex components. We suggest that the fly TIP60 complex regulates epigenetic processes leading to a repressive chromatin state. This is a novel activity of a HAT complex that has previously been implicated in transcription activation and DNA repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and genetics:

The following alleles used in this study were obtained from the Bloomington or Kyoto stock centers, from Jan Larsson, or from Åsa Rasmusson-Lestander: Pc11, Df(3L)Pc, Psc1, Pscvg-D, Psck07834, ph-p410, Pcl7, Pcl11, esc1, esc21, Su(z)124, reptl(3)06945, dMRG15j6A3, Su(var)3-91, In(1)wmottled4h (wm4h), and T(1;4)wm258-21. reptl(3)06945 contains a P[ry+] insertion 17 nucleotides upstream from the ATG within the 5′-UTR, whereas in the dMRG15j6A3 allele, a P[lacW] insertion is present in the dMRG15 second exon, 174 nucleotides downstream from the ATG. Oregon-R was used as the wild-type strain. Pc and rept stocks were balanced over TM3 Sb Ubx-lacZ, over TM6B Tb, or over TM3 Sb to enable identification of homozygous and trans-heterozygous mutant embryos, larvae, and adults. The reptl(3)06945 allele was recombined to a FRT3L-2A [w+] chromosome.

The P element in rept was mobilized using a transposase source, and progeny were scored for loss of the rosy marker gene. reptl(3)06945 [ry+] ry/Δ2-3 Dr ry males were crossed to Ki ry/TM3 ry virgin females and rosy-eyed P* ry/Ki ry male progeny were crossed to CxD/TM3, Sb females to balance the excision chromosome over CxD. Both viable and lethal strains were obtained. Genomic DNA from two of the viable strains was sequenced to confirm that the excisions were precise. One of these, reptex1, was used as a control in the genetic interaction tests.

To make a precise excision of the P[lacW] insertion in dMRG15, we first crossed the dMRG15j6A3 allele with a transposase source and selected progeny that had lost the mini-white marker gene. No homozygous viable w minus strain was obtained, indicating the presence of a second-site lethal mutation on the chromosome. We crossed the w strains to Df(3R)ea, which uncovers the dMRG15 locus, and found one viable precise excision strain. Next, the dMRG15j6A3 [w+] allele was outcrossed to w1118, and recombinants that had lost the second-site lethal mutation were selected by crossing to the dMRG15 precise excision [w−] strain (that still contained the second-site lethal mutation). Viable dMRG15j6A3 [w+]/dMRG15 precise excision [w−] males were selected and crossed to w; CxD/TM3, Sb to establish a clean dMRG15j6A3 stock, designated dMRG15P. To remove the lethal mutation from the dMRG15 precise excision [w−] chromosome, it was recombined with dMRG15P [w+]. Putative w- recombinants balanced over CxD were crossed with the original dMRG15 precise excision/TM3, Sb stock, and viable nonbalancer flies selected. Stocks were established from their Sb siblings, and one of the strains, dMRG15ex1, was used in the genetic interaction experiments.

Genetic interactions with PcG genes were scored by crossing PcG mutant stocks to wild-type, reptex1, reptl(3)06945/TM3, Sb, dMRG15P/TM3, Sb, or dMRG15ex1 flies at 25°. Male progeny were examined for the presence of sex combs on the second and third pair of legs. During the course of these experiments, the penetrance of the extra sex combs phenotype in PcG alleles increased, perhaps because propionic acid was added to the fly food during later stages of this work. However, enhancement of the phenotype by rept or dMRG15 alleles was always compared to control crosses performed in parallel.

Rescue of the genetic interaction was obtained with a reptin cDNA cloned into the pUASp vector (Rorth 1998). The expressed sequence tag (EST) clone LD12420 was PCR amplified with Pfu polymerase and ligated into the XbaI and blunted KpnI sites of the pUASp vector. The construct was sequenced to ensure that no mutations were introduced during PCR and then injected into w1118 flies following standard procedures (Rubin and Spradling 1982). An insertion on the second chromosome was used to establish a w; UASp-reptin; reptl(3)06945/TM3, Sb stock, which was crossed to a w; actin5C-Gal4/+; Pc11/TM3, Sb stock. w; UASp-reptin/actin5C-Gal4; Pc11/reptl(3)06945 males could be distinguished from w; UASp-reptin/+; Pc11/reptl(3)06945 males by their stronger eye color. As a control, we crossed w; UASp-reptin; reptl(3)06945/TM3, Sb flies to a Pc11/TM3, Sb Ser stock. w; UASp-reptin/+; Pc11/reptl(3)06945 males were compared to their w; UASp-reptin/+; Pc11/TM3, Sb brothers.

Pc and rept mutant stocks were crossed to transgenic flies containing Polycomb response elements (PRE) linked to the mini-white reporter gene and the eye color observed in progeny. Different insertions of 8.2 XbaI derived from the Scr gene (Gindhart and Kaufman 1995), two constructs from the Mcp element (44.16.1 and 43.36.B11, construct nos. 19 and 12 described in Muller et al. 1999), and 5F24 from the Fab7 element of the bithorax complex (Cavalli and Paro 1999) were tested.

Effects on position-effect variegation was determined by crossing wm4h females or females carrying P elements with variegating mini-white expression (kindly provided by Lori Wallrath and Steve Henikoff) to wild-type, Su(var)3-91/TM3 Sb Ser, reptex1, or reptl(3)06945/TM3 Sb males at room temperature. The eye color of male progeny was examined, and representative eyes for each genotype were photographed. Modification of Notch variegation was examined by crossing T(1;4)wm258-21 y1 wa/FM4 females to wild-type, Su(var)3-91/TM3 Sb Ser, reptex1, reptl(3)06945/TM3 Sb, dMRG15ex1, or dMRG15P/TM3, Sb males. The number of notches per wing was scored in female progeny without the FM4 balancer chromosome.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry:

Embryos were collected from the reptl(3)06945 stock balanced over TM3, Ubx-lacZ, and from Oregon-R flies (wild-type controls) on apple juice plates and aged appropriately. RNA in situ hybridization using a digoxigenin-labeled antisense rept RNA probe was performed as previously described (Tautz and Pfeifle 1989; Jiang et al. 1991).

Immunohistochemistry was performed essentially as described previously. In brief, reptl(3)06945/TM6 Tb, Pc11/TM3 Sb Ser, and Psc1/CyO mutant stocks were used to generate rept, Pc, and Psc heterozygous as well as rept/Pc and Psc/+; rept/+ mutant third instar larvae. The larvae were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), transferred to ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and fixed for 20 min at room temperature, followed by washes in PBS and PBT (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20). They were blocked in PBSBT (PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 + 0.5% BSA) and incubated with anti-Scr monoclonal antibody 6H4.1 (1:10 dilution, Develpmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) at 4° overnight. After washing with PBSBT, they were developed with the Vectastain ABC Elite kit. After being washed in PBT solution, embryos were rinsed in PBS/50% glycerol, followed by mounting and dissection of leg imaginal discs in 80% glycerol.

Induction of clones and immunofluorescence:

Since reptin mutant clones are very small (data not shown), we used a Minute background. reptl(3)06945 FRT2A/TM6b Tb flies were crossed to yw hsFLP; M(3)i55 hs-nGFP FRT2A/TM6b Tb and F1 larvae were heat-shocked for 1 hr at 37° as first and second instar larvae. Prior to dissection of non-Tb larvae, they were subjected to one more 1-hr heat shock followed by a 1-hr recovery to induce expression of the GFP protein. For detection of GFP mRNA, wing imaginal discs of wandering third instar larvae were dissected immediately after a 30-min heat shock. As a control, we used Su(z)124 FRT2A/TM3 Sb flies crossed to hsFLP; ubi-GFP FRT2A to generate hsFLP; Su(z)124 FRT2A/ubi-GFP FRT2A larvae that were heat-shocked for 1 hr at 37° as first and second instar larvae.

A Ubx 1.6-kb PRE was recombined onto the reptl(3)06945 FRT2A chromosome. A yw; >PBX>-PRE1.6-IDE-Ubx-nlacZ [y+] strain (Fritsch et al. 1999) was crossed with reptl(3)06945 FRT2A flies, and y+ w+ recombinants were selected. These were crossed to a reptl(3)06945/TM6b Tb stock to test for the presence of the reptin mutation. The resulting PRE1.6-lacZ reptl(3)06945 FRT2A/TM6b Tb stock was crossed to yw hsFLP; M(3)i55 hs-nGFP FRT2A/TM6b Tb flies and larval progeny were heat-shocked as described above.

Wing imaginal discs of wandering third instar larvae were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked in block solution (1% BSA in PBT), and incubated with a rabbit β-gal antibody (Cappel) diluted 1:150 or with a monoclonal anti-Ubx antibody (White and Wilcox 1984) diluted 1:75 at 4° overnight. To identify homozygous mutant clones, a rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, Promega, Madison, WI) or a mouse anti-GFP (1:500, Sigma, St. Louis) antibody was mixed with the primary antibodies. Discs were washed in block solution and incubated with Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit (1:500), and Cy2-conjugated anti-mouse (1:200) secondary antibodies (Jackson Laboratories) at room temperature for 2 hr. After being washed in PBT solution, wing discs were rinsed in PBS and in PBS/50% glycerol and then mounted in PBS/80% glycerol. A laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss) was used for confocal imaging. Acquired images were processed with LSM510 software (Zeiss).

Reptin mRNA expression in wing discs was determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization using tyramide signal amplification (TSA; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT). Larvae at the late third instar stage containing reptin mutant clones were dissected, fixed in 1 ml 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. Samples were then washed with PBS, 50% methanol, and methanol and stored at −20° overnight. After five washes in ethanol, samples were incubated in a mixture of xylene and ethanol (1:1) for 60 min, washed five times in ethanol, and rehydrated by immersion in a graded methanol series (80, 50, and 25% v/v in H2O) and finally in H2O. After treatment with acetone (80%) at −20° for 10 min, samples were washed four times with PBT, fixed again in 4% PFA in PBS for 20 min, and washed in PBT. Digoxigenin-labeled reptin and fluorescein-labeled GFP RNA probes were simultaneously added to the samples and hybridized at 55° overnight. After hybridization, samples were washed in PBT and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated antifluorescein antibody (Roche, 1:10,000) for 1.5 hr. FITC-labeled dinitrophenyl (DNP) amplification reagent was used to develop the signal. To wash away the antibody, samples were incubated in 0.01 m HCl twice for 5 min each. Following washes in PBT, peroxidase-coupled antidigoxigenin antibody (Roche, 1:5000) was added to the samples. Cy3-labeled DNP amplification reagent was used to detect the antibody. Discs were dissected, mounted in 80% glycerol, and imaged with a confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Immunoprecipitation:

A Reptin expression plasmid was constructed through amplification of the Reptin open reading frame by PCR from EST clone LD12420. The PCR product was cloned into the EcoRI–XbaI sites of the pAc5.1/V5-His vector to generate a V5-tagged Reptin protein under control of the actin promoter. Similarly, PCR was performed to obtain the dTIP60 open reading frame from EST clone LD31064, and the product was ligated into the EcoRI-digested pRmHa-C-FLAG-His vector. This results in a plasmid expressing the FLAG-tagged dTIP60 protein from the metallothionein promoter.

A stable cell line expressing V5-tagged Reptin was generated as follows. Drosophila Schneider S2 cells were transfected by means of calcium phosphate (DES transfection kit, Invitrogen, San Diego) using a DNA ratio of 19:1 (9.5 μg pAc-Reptin-V5:0.5 μg pCoBlast) and grown in the presence of 50 μg/ml blasticidin. After 2 weeks, resistant clones were replated. The cell line was maintained in medium (Schneider's Drosophila medium with 10% fetal calf serum) containing 10 μg/ml blasticidin.

FLAG-tagged dTIP60 was transfected into the cells stably expressing Reptin-V5 in six-well plates using calcium phosphate. For each well, 2 μg plasmid DNA and 3 ml culture containing 3 × 106 cells were used. Ten microliters of 100 mm copper sulfate stock was added on day 3 to induce dTIP60-FLAG expression. Cells were harvested on day 4 and lysed in a 500-μl lysis buffer (10 mm Tris pH 8.0, 140 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1% NP40, and protease inhibitor cocktail). The protein concentration was determined with Bradford reagent. A fraction of the extract was saved as input. The remaining extract was precleared by incubating with 30 μl protein A sepharose for 1 hr at 4°. Precleared extract was incubated with 2.5 μg rabbit polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma F7425) overnight in a cold room on a rotator. Protein aggregates were removed by spinning the samples at full speed for 10 min, and the supernatants were incubated with 20 μl protein A sepharose for 1 hr at 4°. Beads were washed twice in 1 ml dilution buffer (lysis buffer with 0.1% NP40), once in TSA buffer (10 mm Tris pH 8.0, 140 mm NaCl), and once in 50 mm Tris pH 6.8. Samples were separated on a SDS–10% PAGE gel and blotted onto PVDF membrane (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) overnight. A Western blot was performed using mouse monoclonal anti-V5 antibody (1:5000, Invitrogen) followed by a HRP-linked secondary antibody diluted 1:5000. Enhanced chemiluminescence detection was performed as described by the manufacturer (Amersham). The membrane was reprobed with mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody M2 (1:400, Sigma), which showed that dTIP60-FLAG was expressed at low levels.

RESULTS

Drosophila reptin interacts with PcG mutants:

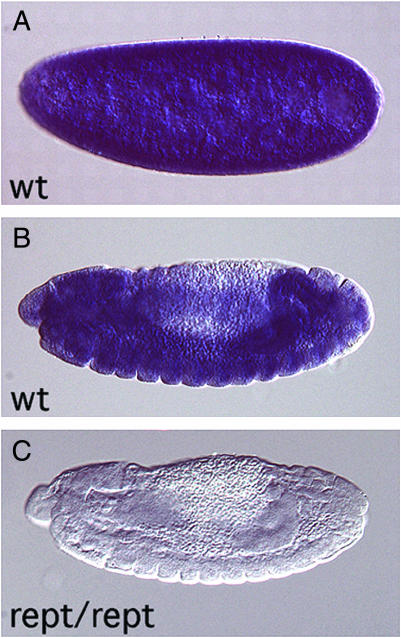

The Drosophila reptin allele l(3)06945 contains a lethal P-element transposon insertion in the 5′ untranslated region of the gene. This insertion causes a dramatic reduction in reptin mRNA levels, as determined by in situ hybridization to l(3)06945 homozygous mutant embryos (Figure 1). We tested whether reptin mutants genetically interact with mutants of PcG genes by creating flies trans-heterozygous for l(3)06945 and PcG genes and examined male progeny for the presence of ectopic sex combs on the second and third pair of legs (Table 1). We compared the trans-heterozygous males with their brothers that do not contain mutations in reptin and to PcG mutants crossed to wild-type males. Under our original culture conditions, heterozygotes of the Pc11 allele do not contain extra sex combs, nor do reptin heterozygous flies (Table 1). However, 47% of males trans-heterozygous for Pc and reptin contain sex combs on the second pair of legs (T2), and 5% additionally contain sex combs on the third pair of legs (T3). Another Pc allele, Df(3L)Pc, causes sex comb development on T2 in 37% of the flies and on T3 in 6% of the flies. The phenotype can be enhanced by reptin to 41% T2 and 25% T3. This genetic interaction indicates that Reptin and Pc participate in the same pathway in vivo.

Figure 1.—

Reptin mRNA expression in wild-type and mutant embryos. Embryos were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled antisense reptin RNA probe and are shown with anterior to the left and dorsal up. (A) A precellular wild-type (wt) embryo shows ubiquitous reptin mRNA expression due to its maternal contribution. (B) At stage 13, reptin is expressed in most tissues in a wild-type embryo. (C) In a stage 13 reptin homozygous mutant embryo, no reptin mRNA can be detected. Mutant embryos were identified with the help of a balancer chromosome expressing a Ubx-lacZ reporter gene.

TABLE 1.

Genetic interactions between reptin and PcG mutants

| % phenotype with sex combs

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | T2 | T3 | n |

| reptl(3)06945/+ | 0 | 0 | 46 |

| Pc11/+ | 0 | 0 | 70 |

| Pc11/reptl(3)06945 | 47 | 5 | 67 |

| Df(3L)Pc/+ | 37 | 6 | 51 |

| Df(3L)Pc/reptl(3)06945 | 41 | 25 | 32 |

| Psc1/+ | 0 | 0 | 63 |

| Psc1/+; TM3/+ | 18 | 0 | 39 |

| Psc1/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 40 | 2 | 53 |

| Pscvg-D/+ | 0 | 0 | 52 |

| Pscvg-D/+; TM3/+ | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| Pscvg-D/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 6 | 2 | 51 |

| Psck07834/+ | 3 | 0 | 38 |

| Psck07834/+; TM3/+ | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Psck07834/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| ph-p410/Y | 90 | 0 | 34 |

| ph-p410/Y; TM3/+ | 100 | 22 | 37 |

| ph-p410/Y; reptl(3)06945/+ | 100 | 100 | 68 |

| esc1/+ | 0 | 0 | 62 |

| esc1/+; TM3/+ | 0 | 0 | 62 |

| esc1/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 0 | 0 | 83 |

| esc21/+ | 0 | 0 | 47 |

| esc21/+; TM3/+ | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| esc21/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 2 | 0 | 50 |

| Pcl7/+ | 0 | 0 | 58 |

| Pcl7/+; TM3/+ | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| Pcl7/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 2 | 0 | 45 |

| Pcl11/+ | 17 | 0 | 81 |

| Pcl11/+; TM3/+ | 30 | 7 | 27 |

| Pcl11/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 47 | 4 | 57 |

| Pc11/reptex1 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| Psc1/+; reptex1/+ | 0 | 0 | 45 |

Percentage of flies containing ectopic sex combs on the second (T2) and third (T3) pair of legs. n, number of flies counted.

To investigate whether the genetic interaction with PcG genes is restricted to members of the PRC1 complex, we examined trans-heterozygous combinations of reptin with two additional PRC1 complex components, Psc and ph, and with two components of the E(z)–Esc complex, namely esc and Polycomb like (Pcl). As shown in Table 1, 40% of Psc1/+; reptin/+ trans-heterozygotes contain ectopic sex combs on T2 and 2% on T3, whereas 18% of the Psc1/+; TM3/+ brothers have sex combs on T2 and none on T3. Psc1/+ heterozygotes do not contain any extra sex combs. A deficiency that removes Psc, Df(2R)vg-D, only weakly interacts with reptin, and a P-element-induced Psc allele, Psck07834, does not interact with reptin at all (Table 1). In the ph allele ph-p410, 90% of the males contain sex combs on T2, but none on T3. When crossed to the reptin mutant stock, we found sex combs on both T2 and T3 in all of the Ph410; reptin/+ mutant males, whereas their Ph410 mutant brothers receiving the TM3 balancer chromosome contain extra sex combs on T2 in 100% and on T3 in 22% of the cases (Table 1), suggesting a specific ph–reptin interaction. In summary, some alleles of three different PcG genes in the PRC1 complex genetically interact with reptin.

Two members of the E(z)–Esc complex, esc and Pcl, were also tested (Table 1). The esc alleles esc1 and esc21 showed either no or a very weak interaction with reptin mutants. However, the number of flies with extra sex combs in one of the two Pcl alleles, Pcl11, was increased by the reptin mutation (Table 1). This shows that the ability of reptin to genetically interact with PcG genes is not restricted to components of the PRC1 complex.

To confirm that the interactions observed are caused by the P-element insertion in reptin, and not due to unidentified second-site mutations on the l(3)06945 chrom osome, we generated precise excisions of the P element. Such excision lines are viable and do not interact with PcG genes (Table 1). Furthermore, expression of the reptin cDNA using an actin-Gal4 driver transgene could rescue the reptin–Pc interaction (Table 2). Under these culture conditions, Pc11 flies contained extra sex combs even in the absence of the reptin mutation. However, the number of sex combs per fly was enhanced by the reptin mutation (Table 2). Introduction of actin-Gal4 and UAS-reptin transgenes into the Pc11/reptinl(3)06945 trans-heterozygous flies reduced the number of sex combs to below the number observed with Pc11 over the balancer chromosome (Table 2). From these data, we conclude that genetic interactions with PcG genes are specifically due to reduced reptin expression in l(3)06945 mutant flies.

TABLE 2.

Rescue of the genetic interaction between reptin and Polycomb mutants

| Phenotype

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % with sex combs

|

Extra sex combs per fly

|

||||

| Genotype | T2 | T3 | T2 | T3 | n |

| UAS-rept; reptl(3)06945/TM3, Sb × act-Gal4/+; Pc11/TM3, Sb | |||||

| UAS-rept/+; Pc11/reptl(3)06945 | 93 | 73 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 15 |

| UAS-rept/act-Gal4; Pc11/reptl(3)06945 | 69 | 25 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 16 |

| UAS-rept; reptl(3)06945/TM3, Sb × Pc11/TM3, Sb Ser | |||||

| UAS-rept/+; Pc11/TM3, Sb | 89 | 89 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 9 |

| UAS-rept/+; Pc11/reptl(3)06945 | 100 | 90 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 10 |

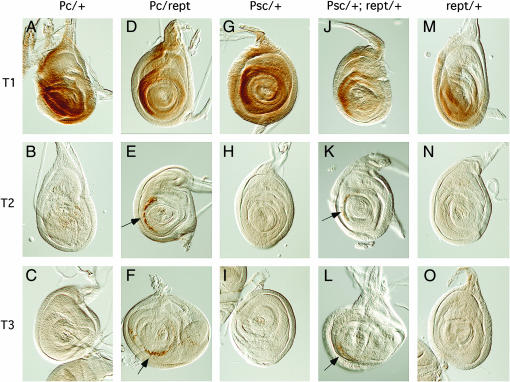

Sex comb development is under the control of the Hox gene Sex combs reduced (Scr). To determine whether Reptin is involved in regulation of Scr expression, we stained leg imaginal discs of third instar larvae with anti-Scr antibody 6H4.1. Scr protein is found in the first thoracic (T1), but not in the T2 and T3 leg discs in wild-type larvae. As shown in Figure 2, reptin/Pc11 and Psc1/+; reptin/+ larvae express Scr protein ectopically in T2 and T3 discs, which reptin, Psc, or Pc heterozygous larvae do not. In conclusion, our genetic data show that Reptin interacts with PcG gene products to control Scr expression.

Figure 2.—

Reptin genetically interacts with Polycomb and Posterior sex combs to induce ectopic expression of Scr in leg imaginal discs. Third instar larvae leg imaginal discs were stained with an antibody recognizing the homeotic protein Scr. In wild-type larvae, Scr is expressed in the first thoracic discs (T1), but not in the second or third thoracic leg discs (T2 and T3). (A–C, G–I, M–O) Pc11, Psc1, and reptl(3)06945 heterozygous larvae have a wild-type Scr expression pattern, being present in T1 but absent from T2 and T3 leg discs. (D–F, J–L) Pc11/reptl(3)06945 and Psc1/+; reptl(3)06945/+ trans-heterozygous larvae ectopically express Scr in T2 and T3 leg discs (arrows in E, F, K, and L) in addition to the normal expression in T1 discs.

A PRE is derepressed in reptin mutant clones:

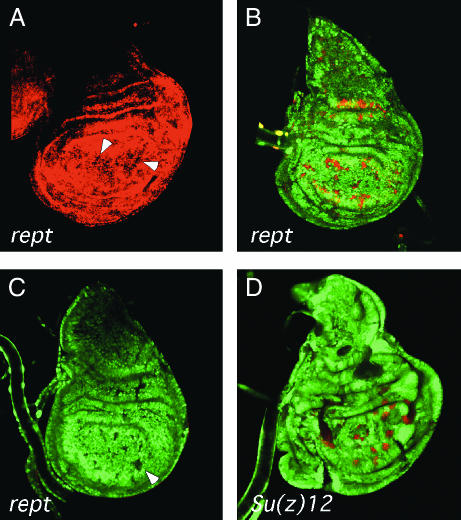

PcG proteins regulate target gene expression through PREs. When linked to the mini-white reporter gene, many PREs show variegated white expression in the eye that is sensitive to PcG gene dosage. We examined several PREs in a reptin heterozygous background and used a PRE from the second intron of the Scr gene (8.2 XbaI), as well as the Fab7 and Mcp PREs from the bithorax complex. Although Pc heterozygotes interacted with all PREs, we did not observe interactions between reptin heterozygotes and any of the PREs tested (data not shown). We generated reptin homozygous mutant cells by mitotic recombination and examined expression of a lacZ reporter gene in wing imaginal discs. This lacZ transgene contains the IDE enhancer and a 1.6-kb PRE from the Ultrabithorax (Ubx) gene (Fritsch et al. 1999). The Ubx gene is repressed in wing imaginal discs by PcG genes, but expressed in haltere discs to prevent acquisition of wing fate. As shown in Figure 3A, reptin mutant clones in wing discs lack reptin mRNA and express the PRE-lacZ reporter (Figure 3B). This indicates that Reptin is necessary for PcG function at this PRE.

Figure 3.—

PRE-controlled gene expression is derepressed in reptin mutant cells, whereas endogenous homeotic gene expression is not. Wing imaginal discs with clones of cells that are homozygous mutant for reptin (A–C) or the PcG gene Su(z)12 (D) were stained for reptin mRNA (A) or with antibodies against GFP (green, B–D) and β-galactosidase (red, B) or Ubx (red, C and D). Clones are marked by the absence of GFP expression. The reptin clones were generated in a Minute background. (A) reptin mRNA is absent from reptin mutant clones (GFP mRNA staining is not shown). (B) A lacZ reporter gene driven by a Ubx enhancer (IDE) and containing a 1.6-kb Ubx PRE is expressed in haltere discs but repressed in wing discs (Fritsch et al. 1999). Strong misexpression of the reporter gene is observed in reptin clones, but not in control wing discs without clones (not shown). (C and D) Misexpression of Ubx is seen in Su(z)12 mutant clones, but not in reptin mutant clones. As expected, Ubx expression was found in all haltere discs (not shown), demonstrating that the staining procedure was successful. The arrowheads in A and C point to some of the clones.

We also examined expression of the endogenous Ubx gene in reptin mutant clones. PcG genes are necessary for silencing of the Ubx gene in wing discs, resulting in ectopic Ubx expression in PcG mutant clones (Beuchle et al. 2001). We stained wing imaginal discs containing homozygous mutant clones of either reptin or the PcG gene Su(z)12 with a Ubx antibody. Figure 3 shows that in wing discs containing Su(z)12 mutant cells, Ubx is ectopically expressed, but in wing discs with reptin mutant cells, it is not. As expected, Ubx was found in all haltere discs (data not shown). It appears that although Reptin is necessary for the activity of the 1.6-kb Ubx PRE, loss of Reptin is not sufficient to derepress endogenous Ubx expression.

We also examined expression of the homeotic genes Scr and Ubx in reptin homozygous mutant embryos. However, no misexpression was observed (data not shown). Reptin is maternally contributed to the embryo, and its mRNA is consequently present ubiquitously in early embryos (Figure 1A). The maternal contribution may mask a regulatory role for reptin in embryonic Hox gene expression. To address this possibility, we attempted to remove the maternal reptin contribution by use of germline clones. However, reptin l(3)06945 homozygous germ cells fail to produce embryos.

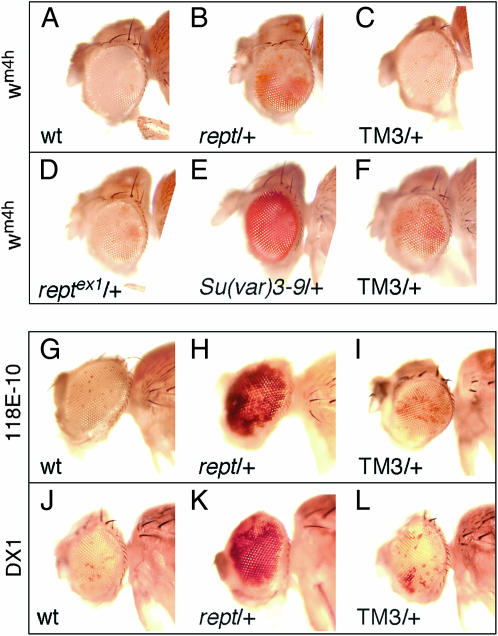

Reptin is a suppressor of position-effect variegation:

We then tested whether reptin mutants affect PEV, a phenomenon resulting in clonal silencing of genes juxtaposed to heterochromatin (Schotta et al. 2003). In In(1)wm4h flies, an inversion on the X chromosome positions the white gene close to pericentric heterochromatin, resulting in a variegated eye color (Reuter and Wolff 1981). We crossed reptin mutants to wm4h flies and compared the progeny to a cross of wm4h with Su(var)3-9 flies. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 by the Su(var)3-9 protein is necessary for heterochromatin formation (Rea et al. 2000; Schotta et al. 2002), and consequently, Su(var)3-9 mutants strongly suppress PEV (Figure 4E; compare with Figure 4, A and F). We found that reptin mutants also suppress variegation of wm4h (Figure 4B; compare with Figure 4, C and D). By contrast, most PcG genes do not affect PEV (Sinclair et al. 1998).

Figure 4.—

Reptin mutants suppress PEV. (A–F) In(1)wm4h (wm4h) flies contain an inversion on the X chromosome that positions the white gene close to pericentric heterochromatin, resulting in a variegated eye color. A known suppressor of variegation, Su(var)3-9, was compared to reptin (rept) mutants. (A) wm4h females were crossed to wild-type males and the eye color of a representative male progeny was photographed. (B and C) Eye color of male progeny from a cross of wm4h females with rept/TM3 males. The reptin mutation (B) suppresses PEV as compared to the same chromosome with a precise excision of the P element (D), as well as compared to the TM3 balancer chromosome (C). (D) Males containing a precise excision of the P element in reptin (reptex1) were crossed to wm4h females. The eye color of a male progeny is shown. (E and F) A Su(var)3-9/TM3 stock was crossed to wm4h females and males receiving the balancer chromosome (F) were compared with their Su(var)3-9 mutant brothers (E). (G–I) A mini-white transgene (118E-10) inserted into centric heterochromatin results in a strongly variegating eye color when crossed with wild-type males (G). Variegation is strongly suppressed by the reptin mutation (H), but not by the TM3 balancer chromosome (I). (J–L) A mini-white transgene array consisting of six copies (DX1) produces a variegating eye color when crossed to wild-type flies (J). When crossed to a rept/TM3 stock, reptin mutant flies suppress variegation (K) compared to their brothers receiving the TM3 balancer chromosome (L).

We investigated whether reptin mutants also suppress other instances of PEV. We examined P-element insertions in telomeric and centric heterochromatin that show variegated mini-white expression (Wallrath and Elgin 1995; Cryderman et al. 1998, 1999). As shown in Figure 4, G–I, and Table 3, reptin mutants suppress PEV of most insertions that respond to classic modifiers of PEV, such as Su(var)3-9. Reptin mutant flies also suppress variegation caused by a mini-white transgene array (DX1, Figure 4, J–L), and variegation of the notched wing phenotype caused by a translocation that positions Notch near pericentric heterochromatin [Table 3, T(1;4)wm258-21]. We conclude that Reptin contributes to generation of silent chromatin at many loci in Drosophila.

TABLE 3.

Reptin and Drosophila MRG15 modify position-effect variagation

| Transgene | Insertion | Responsive to classic modifiersa | Suppressed by reptin mutants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 39C-4 | Centric | Yes | Yes |

| 118E-10 | Centric | Yes | Yes |

| 118E-12 | Centric | Yes | Yes |

| 39C-72 | Telomeric | Yes | Yes |

| 39C-12 | Chromosome 4 | Yes | No |

| 39C-5 | Telomeric | No | No |

| 39C-27 | Telomeric | No | No |

| Genotype | % with wild-type wings | Wing notches per fly | n |

| T(1;4)wm258-21/+; + | 0 | 2.9 | 22 |

| T(1;4)wm258-21/+; Su(var)3-91/+ | 55 | 0.8 | 20 |

| T(1;4)wm258-21/+; reptl(3)06945/+ | 52 | 0.9 | 29 |

| T(1;4)wm258-21/w; + | 0 | 4.6 | 12 |

| T(1;4)wm258-21/w; dMRG15P/+ | 67 | 0.6 | 18 |

| T(1;4)wm258-21/w; dMRG15ex1/+ | 0 | 4.5 | 16 |

Reptin shares with other TIP60 complex components interactions with PcG genes and effects on PEV:

Drosophila Reptin has recently been found in the TIP60 HAT complex (Kusch et al. 2004). In addition to Reptin, this complex contains two other subunits that have been genetically characterized, namely Enhancer of Polycomb [E(Pc)] and Domino. Interestingly, like reptin mutants, E(Pc) and domino mutants enhance PcG phenotypes and suppress PEV (Sinclair et al. 1998; Ruhf et al. 2001). We tested whether an additional TIP60 component, the chromodomain containing protein MRG15 (Bertram and Pereira-Smith 2001), displays similar phenotypes. We used a strain containing a P-element insertion in the second exon of Drosophila MRG15, dMRG15j6A3, and removed a second-site lethal mutation on the chromosome by recombination (see materials and methods). We designated the cleaned chromosome dMRG15P and crossed it to T(1;4)wm258-21 and to PcG mutant flies. Interestingly, dMRG15 mutants suppress Notch variegation (Table 3) and interact with PcG genes (Table 4), whereas a precise excision of the P element does not.

TABLE 4.

Genetic interaction of Drosophila MRG15 with PcG genes

| % phenotype with sex combs

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | T2 | T3 | n |

| dMRG15P/+ | 0 | 0 | 61 |

| Pc11/TM3 | 57 | 32 | 37 |

| Pc11/dMRG15P | 85 | 54 | 39 |

| Pc11/dMRG15ex1 | 54 | 33 | 39 |

| Psc1/+; TM3/+ | 5 | 0 | 38 |

| Psc1/+; dMRG15P/+ | 38 | 11 | 37 |

| Psc1/+; dMRG15ex1/+ | 8 | 0 | 49 |

| esc1/+; TM3/+ | 0 | 0 | 44 |

| esc1/+; dMRG15P/+ | 0 | 0 | 41 |

| esc1/+; dMRG15ex1/+ | 0 | 0 | 55 |

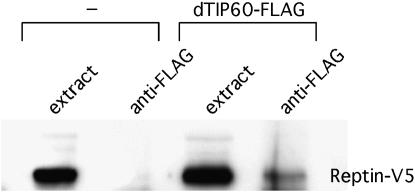

We confirmed that Reptin can physically interact with TIP60 complex components. For this purpose, we expressed tagged proteins in Drosophila S2 tissue-culture cells. As shown in Figure 5, a fraction of V5-tagged Reptin is co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG-tagged dTIP60. These results are consistent with a recent report (Kusch et al. 2004) and show that Reptin can be found in association with the Drosophila TIP60 protein.

Figure 5.—

Reptin interacts with dTIP60. A Drosophila S2 cell line stably expressing V5-tagged Reptin protein was transfected with a plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged dTIP60 under control of the metallothionein promoter. Untransfected cells and transfected cells treated with CuSO4 to induce dTIP60-FLAG expression were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody. The presence of Reptin-V5 in the cell extract and in the immunoprecipitate was detected in a Western blot with anti-V5 antibody.

DISCUSSION

The Reptin protein is present in several chromatin-remodeling complexes. We have shown that, in vivo, Drosophila Reptin is involved in formation of silent chromatin. We propose that Reptin acts as a subunit of the TIP60 HAT complex to generate a repressive chromatin state. This is a novel activity of a HAT complex previously shown to promote transcription (Doyon and Cote 2004).

Drosophila Reptin copurifes with the Polycomb complex PRC1 (Saurin et al. 2001). This prompted us to investigate whether the biochemical interaction with PRC1 was accompanied by a genetic interaction. Table 1 and Figure 2 show that Reptin and PRC1 components genetically interact to regulate expression of the Hox gene Scr. However, Reptin also interacts with a PcG gene product not associated with the PRC1 complex, Pcl. Although we did not detect interactions between reptin heterozygous mutants and several PREs tested, a PRE from the Ubx gene is derepressed in reptin homozygous mutant cells (Figure 3B). This shows that Reptin contributes an essential function to the activity of this PRE. However, unlike most PcG genes, reptin homozygous mutants do not derepress endogenous Hox gene expression (Figure 3 and data not shown). It appears that repression of endogenous Hox genes is more complex and not as sensitive to the loss of Reptin as the Ubx PRE. In contrast to most PcG genes, reptin mutants suppress PEV (Figure 4 and Table 3). Interestingly, derepression of the Ubx PRE also occurs in embryos mutant for other suppressors of PEV (Chan et al. 1994), indicating that this PRE may be highly sensitive to the chromatin environment in its vicinity. Since reptin mutants suppress PEV and fail to derepress endogenous Hox gene expression, we do not consider reptin a bona fide PcG gene, and we find it unlikely that Reptin protein contributes an essential function to the PRC1 complex. In fact, the biochemical activities ascribed to PRC1 can be reconstituted either with recombinant dRing1/Sce (Wang et al. 2004) or with four core components whose activity can be further enhanced by the DNA-binding proteins zeste and GAGA (Mulholland et al. 2003).

Given that Reptin is present in TIP60 complexes in mammals and recently was shown to be a component of a Drosophila TIP60 complex (Ikura et al. 2000; Fuchs et al. 2001; Cai et al. 2003; Doyon et al. 2004; Kusch et al. 2004), we considered the possibility that the genetic interactions observed with PcG genes are due to the presence of Reptin in the fly TIP60 complex. The products of two previously characterized Drosophila genes, E(Pc) and domino, are also present in the TIP60 complex. Strikingly, E(Pc) and domino mutants share with reptin the ability to genetically interact with PcG genes and suppress PEV. E(Pc) is an unusual PcG gene that has very minor effects on Hox gene expression, and unlike most PcG genes, modifies PEV (Soto et al. 1995; Sinclair et al. 1998; Stankunas et al. 1998). In both yeast and humans, E(Pc) homologs form a core complex with Esa1 (TIP60) and Yng2 (ING3) that is sufficient for the nucleosomal acetylation of histones H4 and H2A by the NuA4 complex (Boudreault et al. 2003; Doyon et al. 2004). That such an integral NuA4/TIP60 complex component displays phenotypes similar to reptin mutants suggests to us that Reptin functions through the fly TIP60 complex.

Domino protein is similar to p400 and to SRCAP in mammals and to Swr1 in yeast (Eissenberg et al. 2005). Swr1 has recently been shown to exchange the variant histone H2A.Z (Htz1 in yeast) for H2A in nucleosomes (Krogan et al. 2003; Kobor et al. 2004; Mizuguchi et al. 2004). Intriguingly, an involvement of Htz1 (H2A.Z) in controlling the spreading of silenced chromatin has recently been demonstrated in yeast (Meneghini et al. 2003; Babiarz et al. 2006). Exchange of variant histones may be a conserved feature of chromatin regulation since a recent report demonstrates that Drosophila H2Av behaves genetically as a PcG gene and suppresses PEV (Swaminathan et al. 2005). Domino exchanges phosphorylated and acetylated H2Av for unmodified H2Av after DNA damage (Kusch et al. 2004). However, we found no change in binding of H2Av to polytene chromosomes prepared from domino mutant larvae (data not shown).

A P-element insertion was identified in the gene encoding one additional TIP60 complex component, the chromodomain-containing protein MRG15. Human MRG15 (MORF-related gene on chromosome 15) has been implicated in cellular senescence and regulation of the B-myb promoter (Leung et al. 2001). Both human and yeast (Eaf3/Alp13) MRG15 have been found in Sin3/HDAC complexes in addition to the TIP60 (NuA4) complex (Gavin et al. 2002; Nakayama et al. 2003; Doyon et al. 2004), where it directs the histone deacetylase to coding regions through interaction of its chromodomain with methylated histone H3 lysine 36 (Carrozza et al. 2005; Joshi and Struhl 2005; Keogh et al. 2005). We found that MRG15 mutant flies interact with PcG genes and suppress PEV, just as other TIP60 complex components do. We take this as further support of our conclusion that Reptin's effects on chromatin processes are mediated through its association with the fly TIP60 complex.

What is the basis for the genetic interaction between TIP60 components and PcG genes? One possibility is that the TIP60 complex regulates PcG expression. However, we did not observe reduced Pc expression in reptin mutant embryos (data not shown). Another possibility is that the enzymatic activities of the TIP60 complex cooperate with PcG genes to mediate transcriptional silencing. Since binding of Pc to polytene chromosomes is abolished in H2Av mutant animals (Swaminathan et al. 2005), TIP60 complex-mediated histone variant exchange might cause the genetic interaction with PRC1. However, we found that binding of PcG proteins to polytene chromosomes is unaffected in domino mutant larvae (data not shown). It is possible that PRC1-mediated H2A ubiquitylation helps to recruit the TIP60 complex, whose histone acetylation or histone exchange activity assists in transcriptional repression. Alternatively, histone acetylation or exchange facilitates binding of the PRC1 complex to PREs. A similar mechanism has been invoked for the cooperation of the Esc–E(z) complex and PRC1, where Esc–E(z) trimethylates histone H3 lysine 27, which is recognized by the chromodomain of Polycomb (Fischle et al. 2003; Min et al. 2003).

We have shown that the Drosophila TIP60 complex plays a role in epigenetic gene silencing in vivo. A similar case has been described for the yeast HAT complex SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gen5-acetyltransferase) that is required for both activation and repression of the ARG1 gene (Ricci et al. 2002). Two other yeast HATs, Sas2 and Sas3, also promote gene silencing (Reifsnyder et al. 1996). Interestingly, the Drosophila HAT Chameau suppresses PEV and cooperates with PcG genes as well (Grienenberger et al. 2002). TIP60, Sas2, Sas3, and Chameau are HATs that belong to the MYST family (Utley and Cote 2003). Therefore, MYST family HATs in both yeast and flies can control epigenetic inheritance of silent chromatin.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Larsson for PcG mutant flies, PRE lines and advice, Åsa Rasmusson-Lestander for the FRT Su(z)124 stock and comments on the manuscript, Tom Kaufman and Renato Paro for PRE lines, Lori Wallrath and Steve Henikoff for PEV reporters, Jürg Müller for PRE-lacZ and FRT Minute strains, and the Bloomington and Kyoto stock centers for mutant Drosophila strains. Haojiang Luan constructed the UASp-reptin plasmid. The Scr antibody was developed by D. Brower and obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa. We are grateful to the Christos Samakovlis lab for sharing reagents. This work has been supported by grants from the Åke Wiberg Foundation, the Swedish Cancer Society, and the Swedish Research Council to M.M.

References

- Babiarz, J. E., J. E. Halley and J. Rine, 2006. Telomeric heterochromatin boundaries require NuA4-dependent acetylation of histone variant H2A.Z in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 20: 700–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A., S. Chauvet, O. Huber, F. Usseglio, U. Rothbacher et al., 2000. Pontin52 and reptin52 function as antagonistic regulators of beta-catenin signalling activity. EMBO J. 19: 6121–6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, M. J., and O. M. Pereira-Smith, 2001. Conservation of the MORF4 related gene family: identification of a new chromo domain subfamily and novel protein motif. Gene 266: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuchle, D., G. Struhl and J. Muller, 2001. Polycomb group proteins and heritable silencing of Drosophila Hox genes. Development 128: 993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird, A. W., D. Y. Yu, M. G. Pray-Grant, Q. Qiu, K. E. Harmon et al., 2002. Acetylation of histone H4 by Esa1 is required for DNA double-strand break repair. Nature 419: 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birve, A., A. K. Sengupta, D. Beuchle, J. Larsson, J. A. Kennison et al., 2001. Su(z)12, a novel Drosophila Polycomb group gene that is conserved in vertebrates and plants. Development 128: 3371–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault, A. A., D. Cronier, W. Selleck, N. Lacoste, R. T. Utley et al., 2003. Yeast enhancer of polycomb defines global Esa1-dependent acetylation of chromatin. Genes Dev. 17: 1415–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y., J. Jin, C. Tomomori-Sato, S. Sato, I. Sorokina et al., 2003. Identification of new subunits of the multiprotein mammalian TRRAP/TIP60-containing histone acetyltransferase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 42733–42736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R., L. Wang, H. Wang, L. Xia, H. Erdjument-Bromage et al., 2002. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298: 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrozza, M. J., R. T. Utley, J. L. Workman and J. Cote, 2003. The diverse functions of histone acetyltransferase complexes. Trends Genet. 19: 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrozza, M. J., B. Li, L. Florens, T. Suganuma, S. K. Swanson et al., 2005. Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123: 581–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli, G., and R. Paro, 1999. Epigenetic inheritance of active chromatin after removal of the main transactivator. Science 286: 955–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C. S., L. Rastelli and V. Pirrotta, 1994. A Polycomb response element in the Ubx gene that determines an epigenetically inherited state of repression. EMBO J. 13: 2553–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryderman, D. E., M. H. Cuaycong, S. C. Elgin and L. L. Wallrath, 1998. Characterization of sequences associated with position-effect variegation at pericentric sites in Drosophila heterochromatin. Chromosoma 107: 277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryderman, D. E., E. J. Morris, H. Biessmann, S. C. Elgin and L. L. Wallrath, 1999. Silencing at Drosophila telomeres: nuclear organization and chromatin structure play critical roles. EMBO J. 18: 3724–3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czermin, B., R. Melfi, D. McCabe, V. Seitz, A. Imhof et al., 2002. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 111: 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Napoles, M., J. E. Mermoud, R. Wakao, Y. A. Tang, M. Endoh et al., 2004. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene silencing and X inactivation. Dev. Cell 7: 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon, Y., and J. Cote, 2004. The highly conserved and multifunctional NuA4 HAT complex. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon, Y., W. Selleck, W. S. Lane, S. Tan and J. Cote, 2004. Structural and functional conservation of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex from yeast to humans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 1884–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg, J. C., M. Wong and J. C. Chrivia, 2005. Human SRCAP and Drosophila melanogaster DOM are homologs that function in the notch signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 6559–6569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle, W., Y. Wang, S. A. Jacobs, Y. Kim, C. D. Allis et al., 2003. Molecular basis for the discrimination of repressive methyl-lysine marks in histone H3 by Polycomb and HP1 chromodomains. Genes Dev. 17: 1870–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S. R., T. Parisi, S. Taubert, P. Fernandez, M. Fuchs et al., 2003. MYC recruits the TIP60 histone acetyltransferase complex to chromatin. EMBO Rep. 4: 575–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, C., J. L. Brown, J. A. Kassis and J. Muller, 1999. The DNA-binding polycomb group protein pleiohomeotic mediates silencing of a Drosophila homeotic gene. Development 126: 3905–3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, M., J. Gerber, R. Drapkin, S. Sif, T. Ikura et al., 2001. The p400 complex is an essential E1A transformation target. Cell 106: 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin, A. C., M. Bosche, R. Krause, P. Grandi, M. Marzioch et al., 2002. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gindhart, J. G., Jr., and T. C. Kaufman, 1995. Identification of Polycomb and trithorax group responsive elements in the regulatory region of the Drosophila homeotic gene Sex combs reduced. Genetics 139: 797–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger, A., B. Miotto, T. Sagnier, G. Cavalli, V. Schramke et al., 2002. The MYST domain acetyltransferase Chameau functions in epigenetic mechanisms of transcriptional repression. Curr. Biol. 12: 762–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura, T., V. V. Ogryzko, M. Grigoriev, R. Groisman, J. Wang et al., 2000. Involvement of the TIP60 histone acetylase complex in DNA repair and apoptosis. Cell 102: 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J., T. Hoey and M. Levine, 1991. Autoregulation of a segmentation gene in Drosophila: combinatorial interaction of the even-skipped homeo box protein with a distal enhancer element. Genes Dev. 5: 265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A. A., and K. Struhl, 2005. Eaf3 chromodomain interaction with methylated H3–K36 links histone deacetylation to Pol II elongation. Mol. Cell 20: 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemaki, M., Y. Kurokawa, T. Matsu-ura, Y. Makino, A. Masani et al., 1999. TIP49b, a new RuvB-like DNA helicase, is included in a complex together with another RuvB-like DNA helicase, TIP49a. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 22437–22444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh, M. C., S. K. Kurdistani, S. A. Morris, S. H. Ahn, V. Podolny et al., 2005. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell 123: 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobor, M. S., S. Venkatasubrahmanyam, M. D. Meneghini, J. W. Gin, J. L. Jennings et al., 2004. A protein complex containing the conserved Swi2/Snf2-related ATPase Swr1p deposits histone variant H2A.Z into euchromatin. PLoS Biol. 2: E131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan, N. J., M. C. Keogh, N. Datta, C. Sawa, O. W. Ryan et al., 2003. A Snf2 family ATPase complex required for recruitment of the histone H2A variant Htz1. Mol. Cell 12: 1565–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusch, T., L. Florens, W. H. Macdonald, S. K. Swanson, R. L. Glaser et al., 2004. Acetylation by Tip60 is required for selective histone variant exchange at DNA lesions. Science 306: 2084–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmichev, A., K. Nishioka, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst and D. Reinberg, 2002. Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein. Genes Dev. 16: 2893–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, J. K., N. Berube, S. Venable, S. Ahmed, N. Timchenko et al., 2001. MRG15 activates the B-myb promoter through formation of a nuclear complex with the retinoblastoma protein and the novel protein PAM14. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 39171–39178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S. S., I. F. King and R. E. Kingston, 2004. Division of labor in polycomb group repression. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29: 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino, Y., M. Kanemaki, Y. Kurokawa, T. Koji and T. Tamura, 1999. A rat RuvB-like protein, TIP49a, is a germ cell-enriched novel DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 15329–15335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini, M. D., M. Wu and H. D. Madhani, 2003. Conserved histone variant H2A.Z protects euchromatin from the ectopic spread of silent heterochromatin. Cell 112: 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min, J., Y. Zhang and R. M. Xu, 2003. Structural basis for specific binding of Polycomb chromodomain to histone H3 methylated at Lys 27. Genes Dev. 17: 1823–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi, G., X. Shen, J. Landry, W. H. Wu, S. Sen et al., 2004. ATP-driven exchange of histone H2AZ variant catalyzed by SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex. Science 303: 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland, N. M., I. F. King and R. E. Kingston, 2003. Regulation of Polycomb group complexes by the sequence-specific DNA binding proteins Zeste and GAGA. Genes Dev. 17: 2741–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, J., C. M. Hart, N. J. Francis, M. L. Vargas, A. Sengupta et al., 2002. Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111: 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, M., K. Hagstrom, H. Gyurkovics, V. Pirrotta and P. Schedl, 1999. The mcp element from the Drosophila melanogaster bithorax complex mediates long-distance regulatory interactions. Genetics 153: 1333–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, J., G. Xiao, K. Noma, A. Malikzay, P. Bjerling et al., 2003. Alp13, an MRG family protein, is a component of fission yeast Clr6 histone deacetylase required for genomic integrity. EMBO J. 22: 2776–2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea, S., F. Eisenhaber, D. O'Carroll, B. D. Strahl, Z. W. Sun et al., 2000. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifsnyder, C., J. Lowell, A. Clarke and L. Pillus, 1996. Yeast SAS silencing genes and human genes associated with AML and HIV-1 Tat interactions are homologous with acetyltransferases. Nat. Genet. 14: 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, G., and I. Wolff, 1981. Isolation of dominant suppressor mutations for position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Gen. Genet. 182: 516–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, A. R., J. Genereaux and C. J. Brandl, 2002. Components of the SAGA histone acetyltransferase complex are required for repressed transcription of ARG1 in rich medium. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 4033–4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose, L., and R. Paro, 2004. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38: 413–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth, P., 1998. Gal4 in the Drosophila female germline. Mech. Dev. 78: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottbauer, W., A. J. Saurin, H. Lickert, X. Shen, C. G. Burns et al., 2002. Reptin and pontin antagonistically regulate heart growth in zebrafish embryos. Cell 111: 661–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, G. M., and A. C. Spradling, 1982. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science 218: 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhf, M. L., A. Braun, O. Papoulas, J. W. Tamkun, N. Randsholt et al., 2001. The domino gene of Drosophila encodes novel members of the SWI2/SNF2 family of DNA-dependent ATPases, which contribute to the silencing of homeotic genes. Development 128: 1429–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin, A. J., Z. Shao, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst and R. E. Kingston, 2001. A Drosophila Polycomb group complex includes Zeste and dTAFII proteins. Nature 412: 655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotta, G., A. Ebert, V. Krauss, A. Fischer, J. Hoffmann et al., 2002. Central role of Drosophila SU(VAR)3–9 in histone H3–K9 methylation and heterochromatic gene silencing. EMBO J. 21: 1121–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotta, G., A. Ebert, R. Dorn and G. Reuter, 2003. Position-effect variegation and the genetic dissection of chromatin regulation in Drosophila. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 14: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z., F. Raible, R. Mollaaghababa, J. R. Guyon, C. T. Wu et al., 1999. Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell 98: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X., G. Mizuguchi, A. Hamiche and C. Wu, 2000. A chromatin remodelling complex involved in transcription and DNA processing. Nature 406: 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, D. A., N. J. Clegg, J. Antonchuk, T. A. Milne, K. Stankunas et al., 1998. Enhancer of Polycomb is a suppressor of position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 148: 211–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, M. C., T. B. Chou and W. Bender, 1995. Comparison of germline mosaics of genes in the Polycomb group of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 140: 231–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankunas, K., J. Berger, C. Ruse, D. A. Sinclair, F. Randazzo et al., 1998. The enhancer of polycomb gene of Drosophila encodes a chromatin protein conserved in yeast and mammals. Development 125: 4055–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, B. D., and C. D. Allis, 2000. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl, K., 1998. Histone acetylation and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Genes Dev. 12: 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, J., E. M. Baxter and V. G. Corces, 2005. The role of histone H2Av variant replacement and histone H4 acetylation in the establishment of Drosophila heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 19: 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz, D., and C. Pfeifle, 1989. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma 98: 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utley, R. T., and J. Cote, 2003. The MYST family of histone acetyltransferases. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 274: 203–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallrath, L. L., and S. C. Elgin, 1995. Position effect variegation in Drosophila is associated with an altered chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 9: 1263–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., L. Wang, H. Erdjument-Bromage, M. Vidal, P. Tempst et al., 2004. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature 431: 873–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, R. A., and M. Wilcox, 1984. Protein products of the bithorax complex in Drosophila. Cell 39: 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, M. A., S. B. McMahon and M. D. Cole, 2000. An ATPase/helicase complex is an essential cofactor for oncogenic transformation by c-Myc. Mol. Cell 5: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman, J. L., and R. E. Kingston, 1998. Alteration of nucleosome structure as a mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67: 545–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]