Abstract

Pairing between wheat (Triticum turgidum and T. aestivum) homeologous chromosomes is prevented by the expression of the Ph1 locus on the long arm of chromosome 5B. The genome of Aegilops speltoides suppresses Ph1 expression in wheat × Ae. speltoides hybrids. Suppressors with major effects were mapped as Mendelian loci on the long arms of Ae. speltoides chromosomes 3S and 7S. The chromosome 3S locus was designated Su1-Ph1 and the chromosome 7S locus was designated Su2-Ph1. A QTL with a minor effect was mapped on the short arm of chromosome 5S and was designated QPh.ucd-5S. The expression of Su1-Ph1 and Su2-Ph1 increased homeologous chromosome pairing in T. aestivum × Ae. speltoides hybrids by 8.4 and 5.8 chiasmata/cell, respectively. Su1-Ph1 was completely epistatic to Su2-Ph1, and the two genes acting together increased homeologous chromosome pairing in T. aestivum × Ae. speltoides hybrids to the same level as Su1-Ph1 acting alone. QPh.ucd-5S expression increased homeologous chromosome pairing by 1.6 chiasmata/cell in T. aestivum × Ae. speltoides hybrids and was additive to the expression of Su2-Ph1. It is hypothesized that the products of Su1-Ph1 and Su2-Ph1 affect pairing between homeologous chromosomes by regulating the expression of Ph1 but the product of QPh.ucd-5S may primarily regulate recombination between homologous chromosomes.

CROSSING over between homeologous chromosomes in allotetraploid wheat (Triticum turgidum, genomes AABB) and allohexaploid wheat (T. aestivum AABBDD) is prevented by the expression of the Ph1 locus on the long arm of chromosome 5B (Okamoto 1957; Riley and Chapman 1958; Sears and Okamoto 1958; Riley 1960). This locus allows crossing over to take place only between homologous chromosomes. Because the Ph1 locus is in the B genome, it was logical to expect that it was contributed to polyploid wheats by the diploid source of the B genome, which was most likely an extinct close relative of Aegilops speltoides (2n = 2x = 14, genomes SS) (Sarkar and Stebbins 1956; Dvorak and Zhang 1990; Dvorak 1998). The Ae. speltoides genome was therefore expected to compensate for the absence of Ph1 in T. aestivum × Ae. speltoides hybrids nullisomic for chromosome 5B. Surprisingly, high levels of homeologous chromosome pairing rather than a suppression were observed in the hybrids, not only in the absence of chromosome 5B but also in its presence (Riley 1960). Ae. speltoides is naturally variable for the ability to elicit homeologous chromosome pairing in hybrids with wheat (Dvorak 1972; Kimber and Athwal 1972). A virtual continuum of chromosome-pairing levels, ranging from a few to ∼16 chiasmata/metaphase I (MI) cell, has been observed in various T. aestivum × Ae. speltoides hybrids, strongly suggesting that the trait is under complex genetic control in the Ae. speltoides genome (Dvorak 1972). Segregation analyses of crosses between various Ae. speltoides strains suggested that the trait is controlled by a minimum of two unlinked major loci interacting in a duplicate manner and an unknown number of minor genes (Chen and Dvorak 1984).

Feldman and Mello-Sampayo (1967) suggested that Ae. speltoides affects homeologous chromosome pairing in wheat × Ae. speltoides hybrids by promoting homeologous chromosome pairing per se. Dover and Riley (1977) pointed out that variation in homeologous chromosome pairing in T. aestivum × Ae. speltoides hybrids occurs only if Ph1 is present and therefore proposed that the Ae. speltoides genome affects homeologous chromosome pairing by suppressing the activity of Ph1.

If the Ae. speltoides genome affects homeologous chromosome pairing by suppressing the expression of Ph1, then Ae. speltoides genotypes that bring about different levels of homeologous chromosome pairing in wheat × Ae. speltoides hybrids would bring about the same level of homeologous pairing in hybrids with species that do not show a Ph1-like activity. To test this hypothesis, Ae. speltoides lines differing greatly in the ability to elicit homeologous chromosome pairing in wheat × Ae. speltoides hybrids were crossed with diploid Ae. tauschii and Ae. caudata, which do not show a Ph1-like activity. No meaningful differences between the hybrids were found, indicating that Ae. speltoides genes act on the Ph1 locus (Chen and Dvorak 1984).

A great deal of work has been done on the characterization of the Ph1 locus and its expression, culminating with the recently reported comparative sequencing of >2 Mbp of the Ph1 region (Griffiths et al. 2006). A conclusion was reached that Ph1 activity is synonymous with the insertion of heterochromatin from chromosome 3A into the cdc2 multigene locus in the Ph1 region on chromosome 5B (Griffiths et al. 2006).

Following the rationale that the isolation and molecular characterization of Ae. speltoides Ph1 suppressors will assist with illuminating the molecular basis of this important meiotic mechanism, we embarked on genetic characterization and mapping of Ae. speltoides Ph1 suppressors, with the ultimate goal of isolating these genes. This work was made possible by the development of a genetic map of the Ae. speltoides genome (Luo et al. 2005). The Ae. speltoides map revealed that recombination is localized in very short distal regions of the Ae. speltoides chromosomes. As a result, most markers cluster into centromeric blocks with little or no recombination while the distances between distal markers are expanded, often generating separate linkage groups (Luo et al. 2005). These characteristics of Ae. speltoides meiosis make it difficult to use molecular markers effectively in traditional QTL mapping. We therefore employed several strategies with progressively increasing precision to detect and map loci that interact with the Ph1 locus in the Ae. speltoides genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plants and mapping populations:

Ae. speltoides population 2-12-4, eliciting low homeologous chromosome pairing in hybrids with T. aestivum cv “Chinese Spring,” and population PI369609-12-II, eliciting high homeologous chromosome pairing in hybrids with Chinese Spring, were used. T. aestivum is a self-pollinating species but Ae. speltoides is a cross-pollinating species. Repeated self-pollination of Ae. speltoides plants resulted in sterility of the plants. The original open-pollinated Ae. speltoides accessions were therefore self-pollinated for two generations and then maintained as populations of interbreeding plants. Hybrids of Chinese Spring with the Ae. speltoides population 2-12-4 had ∼7–9 chiasmata/cell at MI and those with the PI369609-12-II population had ∼15–16 chiasmata/cell at MI (Chen and Dvorak 1984). Haplotypes contributed by the 2-12-4 population are designated as a-haplotypes and those contributed by the PI369609-12-II population are designated as b-haplotypes.

A total of 50 Ae. speltoides F2 plants were crossed with Chinese Spring and from 1 to 29 hybrids were produced per each of the 50 F2 plants and grown in a greenhouse. The mean number of chiasmata per cell was estimated in 15–30 meiocytes in anthers from one or two spikes. Mean chiasma number per cell was computed for each hybrid and each family of hybrids. These 50 F2 plants were also among the 86 F2 plants used for the construction of the Ae. speltoides genetic map (Luo et al. 2005).

An additional 30 F2 plants were grown and crossed with Chinese Spring. From 2 to 154 hybrids/family were grown in the greenhouse. The mean number of chiasmata per cell was determined in 15–30 meiocytes for each hybrid. DNAs were isolated from 590 hybrids and Southern blots were prepared and hybridized with 35 cloned DNA fragments. The association of QTL with marker loci detected by these DNA fragments was tested by partitioning the population into a- and b-haplotype subpopulations and testing the difference between mean phenotypic scores of the subpopulations with one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA). These analyses indicated the approximate locations of the QTL. For further analyses, 317 hybrids derived from 19 F2 plants heterozygous at loci associated with each QTL were selected. This population was used to estimate the effect of the substitution of the b- for the a-haplotype at each of the 35 marker loci in the background of low-homeologous-chromosome-pairing haplotypes at QTL loci detected in the previous analyses.

Mapping of major loci:

To locate major loci suppressing Ph1 on the Ae. speltoides genetic map, progeny of the Ae. speltoides F2 plant 125, which was heterozygous at RFLP markers associated with all QTL detected, were grown in isolation. DNAs were isolated from F3 plants, desired genotypes were selected on the basis of RFLP, and plants were grown in isolation. The same process was repeated in the F4 generation. Plants segregating at markers associated with a single QTL, but homozygous for low-pairing haplotypes at loci associated with the remaining QTL, were crossed with Chinese Spring. Numbers of chiasmata per cell were determined using from two to five spikes per hybrid as replicates. DNAs were isolated from the hybrids and used in RFLP mapping of Ph1 suppressors relative to molecular markers.

One of the Ph1 suppressing loci was mapped near Xpsr1205 on chromosome 3S. After the first round of mapping, the locus was flanked by wheat EST markers XBF497740 and XBE488620. To map this Ph1 suppressor relative to other molecular markers on the Ae. speltoides genetic map, five Ae. speltoides F4 plants heterozygous at the Xpsr1205, XBF497740, and XBE488620 loci, but homozygous for low-pairing haplotypes at QTL on other chromosomes, were crossed with Chinese Spring and 269 hybrids were grown. DNAs were isolated from each plant using the rapid DNA isolation technique described below. XBF497740 and XBE488620 genotypes were determined using dominant PCR assays. Xpsr1205 genotypes were determined with a TaqMan assay. To detect Ae. speltoides DNA fragments in Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids, PCR primer pairs that amplified only Ae. speltoides target DNA from genomic DNA of Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids were designed (see below). Hybrids that harbored chromosomes that had undergone recombination in the XBF497740–XBE488620 interval were kept. At least five immature spikes were harvested for meiotic analyses from these plants and DNAs were isolated from the remaining plant material for RFLP.

Interspecific hybridization:

Chinese Spring and Ae. speltoides plants were grown in clay pots in the greenhouse. Chinese Spring flowers were manually emasculated and hand pollinated with Ae. speltoides pollen 2 days after emasculation and then repollinated the next day. Virtually all hybrid seeds were shriveled. They were sterilized with a 0.5 dilution of commercial bleach in distilled water for 15 min, thoroughly rinsed in distilled water, and dried for 1 min on sterile filter paper. They were then placed on sterile filter paper moistened with a sterile solution containing 100 mg/liter of ampicillin, 60 g/liter sucrose, and 400 mg/liter glutamine. Petri dishes were kept at 5° in a refrigerator for 5 days. Seeds were transferred into fresh petri dishes with filter papers moistened with the above solution and germinated at 26°. Seedlings were transplanted directly into Jiffy peat pots or clay pots in the greenhouse.

Meiotic analyses:

Immature spikes were collected from greenhouse-grown plants and fixed in a freshly prepared solution of 6 ethanol:3 chloroform:1 glacial acetic acid, v/v, for 24 hr at room temperature. Spikes were rinsed in 70% ethanol and stored in 70% ethanol in refrigerator until analyzed. Squashes of meiocytes were prepared with the standard aceto-carmine method. Slides were systematically scanned under the microscope and the numbers of chiasmata were determined in 10–30 meiocytes per spike. Only anthers in which the majority of meiocytes were at MI were used.

DNA isolation and DNA hybridization:

A rapid DNA isolation technique was employed for PCR-based assays (J. L. Halverson and A. Van Deynze, personal communication). A 6-cm2 segment of seedling leaf was placed into each well of a 96-well flat-bottom block (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, catalog no. 19579). Two 8-mm stainless-steel grinding lapidary ball/cones were inserted into each well, and the plate was heat sealed and frozen at −80 for at least 3 hr. A hole was punched through the seal of each well with a 12-gauge needle, and the whole plate was lyophilized overnight. The plate was sealed with a plate tape (QIAGEN, catalog no. 19570) immediately after lyophilization, and the samples were ground by shaking on a commercial paint shaker in two orientations for 30 sec each. Holes were punched through the film covering each well with a 12-gauge needle and widened with the conical bottoms of a PCR plate. One milliliter of fresh lysis buffer containing 500 mm NaCl, 100 mm Tris pH 7.2, 50 mm EDTA, 0.5% sodium bisulfite, 0.1% diethyldithiocarbamic acid, 0.1% ascorbic acid, and 2% polyvinylpolypyrillidone was added to each well while hand agitating the solution. The plate was sealed with plate tape and inverted several times until the plant material was uniformly wetted. A hole was punched into each well using an 18-gauge needle and the plate was incubated at 65° for 45 min. The tape and foil were carefully removed from the plate. A total of 800 μl of solution was transferred with a 1000-μl multi-channel pipette from each well into a round-bottom 96-well block and sedimented at 2000 × g for 10 min. A total of 400 μl of supernatant was transferred from each well into a new round-bottom 96-well block, making sure that no particulate matter was transferred, 400 μl isopropanol was added, the wells were sealed with tape, and the plate was inverted four times. DNAs were sedimented at 3000 rpm for 10 min, supernatant was poured off, and the pellet was rinsed with 70% ethanol, air dried for 30 min, and dissolved in 200 μl of 10 mm TRIS and 1 mm EDTA. A total of 3 μl of the DNA solution was used per PCR reaction.

For RFLP, nuclear DNA was isolated as described by Dvorak et al. (1988). To prepare Southern blots, DNAs were digested with restriction endonucleases and Southern blots were hybridized as described earlier (Dvorak et al. 2004).

Design of Ae. speltoides genome-specific primers for EST loci and TaqMan assay:

Sequence information for wheat ESTs BE497740 and BE442875 was obtained from the wheat EST database (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/NSF/). Homology was searched with these sequences in the rice genomic sequence using BLASTN at the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) site. Intron/exon junctions were identified in the rice genomic sequence and primers were designed using the wheat EST sequence to flank an intron. Genomic DNAs of Ae. speltoides (F2 family no. 134), Ae. tauschii (AL8/78 and AS75), T. urartu (G1812 and DV867), T. dicoccoides (PI428094), and “Langdon” durum wheat were used as templates in PCR. Amplicons from T. dicoccoides and Langdon were TA cloned (pGEM-T vector system, Promega, Madison, WI). Amplicons were sequenced in both directions using PCR primers as DNA-sequencing primers. Sequences were aligned and compared. Nucleotide positions at which the Ae. speltoides nucleotide sequence differed from the T. urartu, Ae. tauschii, and wheat A- and B-genome nucleotide sequences were used to design Ae. speltoides genome-specific primers. Their specificity was tested using genomic DNAs of wheat/Ae. speltoides disomic addition lines (Friebe et al. 2000) and 10 Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids, which had shown contrasting RFLP haplotypes at the XBE497740, XBE442875, and Xpsr1205 loci. Ae. speltoides genome-specific PCR primers were developed for all three markers (Table 1). Those for the XBE497740 and XBE442875 loci fortuitously also differentiated between the Ae. speltoides a- and b-haplotypes, providing an amplicon presence vs. absence PCR-genotyping test. PCR primers for Xpsr1205 (Table 1) showed no such differentiation. PCR amplicons of Ae. speltoides Xpsr1205a and Xpsr1205b RFLP haplotypes were sequenced and sequences were compared. The differences between the Xpsr1205a and Xpsr1205b sequences were exploited for the design of TaqMan primers and probes (Table 2). PCR primers and TaqMan probes were designed by Applied BioSystems (Foster City, CA).

TABLE 1.

Ae. speltoides genome-specific PCR primers for amplification of DNA from the indicated loci in wheat × Ae. speltoides hybrids

| Locus | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Xpsr1205 | CGGCAATGATGAGTGTGTCATT | CAACTCCCAGTTTGCTGACA |

| Xbe442875 | TTAGGTAGTTTTTGTTTTGTTTCATT | TGCCCCGAAACAGAGATG |

| Xbe497740 | CCTGATTACCTCCGTATAAAAAAT | TCAGGAGCAATAGTTTTC TTGTCA |

TABLE 2.

Xpsr1205 PCR primers and TaqMan probe for detecting A/G single nucleotide polymorphism at the Xpsr1205 locus

| Primer or probe | Dye | Nucleotide sequence |

|---|---|---|

| PCR forward | — | GCACCCAGCTTGTATTGATTTCCT |

| PCR reverse | — | GTGCCCTTCACGCTAGCA |

| TaqMan probe 1 | VIC | CATGACGGAAAGATAT |

| TaqMan probe 2 | FAM | CATGACGGAGAGATAT |

FAM, fluorescein phosphoramide.

PCR conditions:

The following conditions were used for PCR amplification of DNA from the Xpsr1205 and XBE442875 loci: 96° for 5 min, 10 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 59° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min, followed by 10 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 57° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min, followed by 20 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 56° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min, with a final extension at 72° for 5 min.

The conditions for PCR amplification of DNA from the XBE497740 locus were 96° for 5 min, followed by 10 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 57° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min, 10 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 55° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min, and 20 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 54° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min, followed by extension at 72° for 5 min.

For the XBE497740 locus, PCR with Ae. speltoides genome-specific primers (Table 1) generated amplicons only for the XBE497740 b-haplotype, which was 150 bp long. For the XBE442875 locus, PCR with Ae. speltoides genome-specific primers (Table 1) generated amplicons only for the XBE442875 a-haplotype, which was ∼250 bp long.

Using the Ae. speltoides genome-specific PSR1205 primers (Table 1), an amplicon of ∼400 bp was produced for both haplotypes. The PCR reaction was diluted 1:100 with distilled water and 1 μl was used as a template for the TaqMan assay. Since the TaqMan forward and reverse primers (Table 2) were not Ae. speltoides-genome specific, it was important that the amount of genomic DNA present was minimized. The TaqMan assay was carried out according to the manufacturer's (Applied BioSystems) specifications. ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied BioSystems) was used for real-time PCR.

Statistical analyses:

Restriction fragment length polymorphism at 137 loci detected by hybridization of 99 cDNA or PstI clones (Luo et al. 2005) in 50 F2 plants was employed in the construction of a genetic map using MapMaker 3.0 (Lincoln et al. 1992) and in correcting segregation data with the Kosambi mapping function (Kosambi 1943). MapMaker QTL function was used to compute LOD scores of associations between molecular markers and mean numbers of chiasmata computed for each of the 50 families of Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids.

The statistical significance of differences in the size of intervals between markers on different genetic maps was tested as follows. Interval lengths in centimorgans were converted into recombination fractions. Variances of the estimates were computed according to Allard (1956). The differences in the interval lengths between maps were tested by z-test.

The association between molecular markers and the level of homeologous chromosome pairing was estimated in the population of 590 Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids. Southern blots of DNAs of the 590 hybrids were hybridized with clones detecting 35 strategically placed RFLP loci. Allelic variation at each locus was determined. For each locus, hybrids were grouped into two subpopulations, one containing the a-haplotype and the other the b-haplotype. The difference between mean chiasma numbers per cell between the two subpopulations, F-value, and probability were computed with one-way analysis of variance. Similar analyses of variance were performed for groups of selected hybrids as described in results.

To assess the statistical significance of interactions between and among QTL, 3 × 2 factorial ANOVA was performed using the mean numbers of chiasmata per cell as variables with the GLM procedure of SAS 9.1.

RESULTS

QTL analysis:

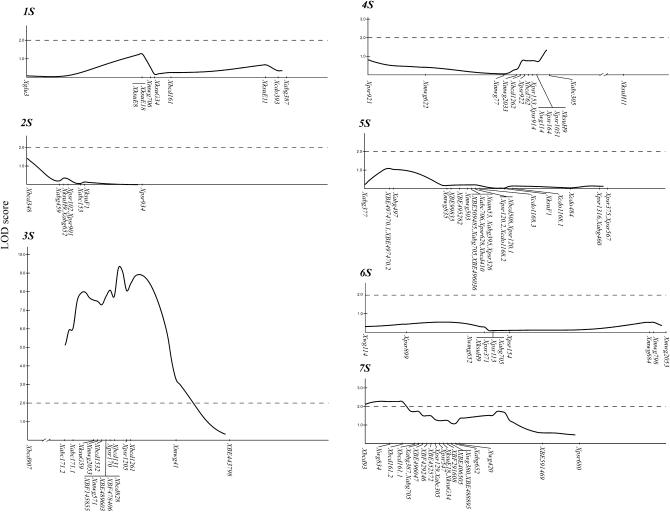

Because parental stocks 2-12-4 and PI369609-12-II were not homozygous, only a single Ae. speltoides F1 plant from the cross 2-12-4 × PI369609-12-II was used to produce all mapping populations. Fifty F2 plants were crossed with Chinese Spring, producing 50 families of hybrids. The mean numbers of chiasmata were scored in one to two spikes per hybrid, and family means were computed. DNAs were isolated from the 50 F2 plants, a genetic map based on 137 RFLP loci was constructed, and QTL analysis was performed using the family mean numbers of chiasmata per cell as the phenotypic scores. The limited number of families, low recombination rates in proximal chromosome regions, and high recombination rates in the distal regions limited the resolution of the analysis. Using a LOD score of 2.0 as the significance boundary, QTL were detected on chromosomes 3S and 7S but their locations relative to molecular marker loci were uncertain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.—

LOD score plots of associations between mean numbers of chiasmata per cell in Chinese spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids and molecular markers along the linkage maps of Ae. speltoides chromosomes. Markers forming separate linkage groups but known to be on the indicated Ae. speltoides chromosome are disconnected from the rest of the chromosome. A LOD score of 2.0 is indicated on each chromosome graph.

The high-pairing QTL haplotype on chromosome 3S cosegregated with the recessive lig gene for awnless lateral spikelets that is in the centromeric region of the 3S genetic map (Luo et al. 2005). Awnless lig/lig plants were excluded from being parents in further crosses with Chinese Spring to minimize the likelihood of including Ae. speltoides plants homozygous for the high-pairing QTL haplotype in the crosses.

A total of 30 additional F2 Ae. speltoides plants with awned lateral spikelets (Lig/lig or Lig/Lig) were selected and crossed with Chinese Spring. Mean chiasma numbers per cell were estimated in 590 hybrids and DNAs were isolated from them. Southern blots were prepared and hybridized with 35 PstI or cDNA clones, each detecting a single locus in the Ae. speltoides genome. The positions of the loci on the Ae. speltoides genetic map were determined earlier (Luo et al. 2005). The analysis of QTL effects and their location was performed in several cycles.

The objective of the first cycle of analysis (not shown) was to identify marker loci associated with major QTL. The population of 590 hybrids was partitioned into the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations at each marker locus and the mean numbers of chiasmata per cell were computed for each subpopulation. The largest differences in chiasma number per cell between the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations were observed for the markers on chromosomes 3S and 7S. On chromosome 3S, the largest difference was at the Xpsr1205 locus on the long arm. On chromosome 7S, the largest difference was at the Xpsr129 locus on the long arm. High pairing was associated with the b-haplotype at both marker loci. A total of 23 families comprising 468 hybrids derived from Ae. speltoides parents heterozygous at the Xpsr1205 and Xpsr129 loci were used for further analyses.

The objective of the second cycle of analysis was to search for minor QTL on the remaining five chromosomes. A subpopulation of 177 Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids of genotype Xpsr1205a × Xpsr129a (low-pairing haplotype at both loci) was selected and used to search for QTL on Ae. speltoides chromosomes 1S, 2S, 4S, 5S, and 6S. For each investigated locus on these five chromosomes, the population was subdivided into the a- and b-haplotypes and the probability that the difference in mean chiasma number per cell between a pair of subpopulations was due to chance was estimated with one-way ANOVA. Several iterations of this cycle were performed, each resulting in associating a QTL with a marker locus with greater precision. In addition to substantiating the association of major QTL with Xpsr1205 and Xpsr129 loci, a minor QTL was associated with marker locus Xabg705 in the short arm of chromosome 5S.

In the third cycle of analysis, 317 hybrids, derived from 19 Ae. speltoides F2 plants that were simultaneously heterozygous and hence segregated at the Xpsr1205, Xabg705, and Xpsr129 loci, were analyzed. For analyses of the effects of marker loci on chromosomes 1S, 2S, 4S, and 6S, a population of 70 hybrids with genotype Xpsr1205a × Xabg705a × Xpsr129a was selected. This population was individually partitioned into the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations at each marker locus on these four chromosomes (Table 3). For analyses of marker effects on chromosome 3S, a population of 107 hybrids with genotype Xabg705a × Xpsr129a was selected from the 317 hybrids. For analyses of marker effects on chromosome 5S, a population of 134 hybrids of genotype Xpsr1205a × Xpsr129a was selected from the 317 hybrids. Finally, for analyses of marker effects on chromosome 7S, a population of 125 hybrids with genotype Xpsr1205a × Xabg705a was selected from the 317 hybrids.

TABLE 3.

The effects of the substitution of the b-haplotype for the a-haplotype at indicated loci on the mean chiasma number per cell in subpopulations of Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids and one-way ANOVA of the difference between the means of a-haplotype and b-haplotype subpopulations

| Chromosome | Locus | No. of hybrids in smaller subpopulation | b-Haplotype subpopulation mean minus a-haplotype subpopulation mean | F | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | XksuE18 | 13 | −0.5 | 0.4 | 0.513 |

| 1 | Xbcd161 | 20 | −1.0 | 2.7 | 0.106 |

| 1 | Xcdo393 | 37 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.308 |

| 2 | Xbcd348 | 32 | −0.1 | <0.1 | 0.818 |

| 2 | Xpsr102 | 31 | −0.1 | <0.1 | 0.937 |

| 2 | Xbcd111 | 30 | −0.1 | <0.1 | 0.911 |

| 2 | Xbcd1069 | 31 | −0.1 | <0.1 | 0.938 |

| 3 | Xabc171 | 49 | 5.3 | 61.3 | <0.001 |

| 3 | XksuG59 | 35 | 7.0 | 131.0 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Xbcd1532 | 36 | 6.6 | 111.8 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Xbcd828 | 35 | 7.0 | 137.8 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Xbcd131 | 35 | 7.3 | 163.9 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Xpsr1205 | 34 | 8.4 | 390.8 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Xbcd1261 | 35 | 8.1 | 315.5 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Xmwg41 | 41 | 4.6 | 37.7 | <0.001 |

| 4 | Xwg622 | 14 | −1.2 | 1.6 | 0.210 |

| 4 | Xmwg2033 | 42 | −0.6 | 1.0 | 0.326 |

| 4 | Xbcd1262 | 40 | −0.4 | 0.4 | 0.544 |

| 4 | XksuH11 | 33 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 0.735 |

| 5 | XBE497470 | 33 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.665 |

| 5 | Xabg705 | 62 | 1.6 | 6.9 | 0.009 |

| 5 | Xpsr628 | 63 | 1.5 | 6.9 | 0.010 |

| 5 | Xbcd508 | 61 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 0.035 |

| 5 | XksuF1 | 36 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.295 |

| 5 | Xcdo484 | 13 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.615 |

| 6 | Xpsr899 | 13 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 0.105 |

| 6 | Xpsr113 | 30 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.153 |

| 7 | Xbcd93 | 17 | 3.5 | 25.7 | <0.001 |

| 7 | XBF429246 | 46 | 5.4 | 138.6 | <0.001 |

| 7 | XBF442572 | 47 | 5.4 | 139.2 | <0.001 |

| 7 | Xpsr129 | 52 | 5.8 | 215.0 | <0.001 |

| 7 | Xpsr547 | 51 | 5.6 | 183.5 | <0.001 |

| 7 | Xwg380 | 48 | 5.6 | 168.8 | <0.001 |

| 7 | XBE406505 | 46 | 4.8 | 89.6 | <0.001 |

| 7 | Xpsr680 | 17 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.717 |

Chromosomes 1S, 2S, 4S, and 6S:

The population of 70 hybrids with the a-haplotype at the Xpsr1205, Xabg705, and Xpsr129 loci was divided into the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations at RFLP marker loci on these four chromosomes and one-way ANOVAs were performed. The magnitude of the difference between the means, the F-value, and the probability that the difference between the means was due to chance alone were computed for each marker locus. None of the differences between the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations was significant (Table 3).

Chromosome 3S:

The population of 107 hybrids with the a-haplotype at the Xabg705 and Xpsr129 marker loci was divided into the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations at each of the eight investigated loci on chromosome 3S. All eight b-haplotype subpopulations had significantly higher mean chiasma number per cell than the corresponding a-haplotype subpopulations (Table 3). The magnitude of the difference and the F-value were the largest at the Xpsr1205 locus in the distal portion of the long arm. The substitution of the Xpsr1205b haplotype for the Xpsr1205a haplotype increased homeologous chromosome pairing in Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids by 8.4 chiasmata/cell.

Chromosome 5S:

The population of 134 hybrids with the a-haplotype at marker loci Xpsr1205 and Xpsr129 was partitioned into the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations for each of the six investigated loci on chromosome 5S. The difference between the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations and the F-value reached the largest magnitude at the Xabg705 and Xpsr628 loci, suggesting that a QTL is located in the short arm of the chromosome in interval Xabg705–Xpsr628. The substitution of the Xabg705b haplotype for the Xabg705a haplotype increased homeologous chromosome pairing by 1.6 chiasmata/cell in Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids.

Chromosome 7S:

The population of 125 hybrids with genotype Xpsr1205a and Xpsr129a was divided into the a- and b-haplotype subpopulations at each of the eight investigated loci on this chromosome. At all marker loci, except for Xpsr680, the most distal locus on the long arm, the b-haplotype subpopulation had significantly higher homeologous chromosome pairing than the corresponding a-haplotype subpopulation. The magnitude of the difference between a pair of subpopulation means and the F-value were the greatest at Xpsr129. The substitution of the Xpsr129b haplotype for the Xpsr129a haplotype increased homeologous chromosome pairing by 5.8 chiasmata/cell in hybrids.

Gene interactions:

Interactions between the three QTL were examined by factorial ANOVA in which Xpsr1205, Xabg705, and Xpsr129 were factors, each having two haplotype levels. Mean chiasma numbers per cell in 317 hybrids belonging to 19 families segregating simultaneously at the Xpsr1205, Xabg705, and Xpsr129 loci were used as variables. An R2 of 0.78 indicated that the effects of the three marker loci explained most of the variation in this population. The effect of each marker locus was highly significant (Table 4). Also highly significant were interactions between the QTL associated with the Xpsr1205 marker and the QTL associated with markers Xabg705 and Xpsr129. No interaction was detected between QTL associated with the latter two markers. Nor did ANOVA indicate a three-way interaction among the loci (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

ANOVA table for 3 × 2 factorial design testing the effects of individual QTL associated with markers Xpsr1205, Xpsr628, and Xpsr129 on chromosomes 3S, 5S, and 7S, respectively

| Source | d.f. | Sum of squares | Mean square | F-value | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 7 | 4010.7 | 572.9 | 159.8 | <0.0001 |

| Xpsr1205 | 1 | 1553.6 | 1553.6 | 433.3 | <0.0001 |

| Xabg705 | 1 | 80.7 | 80.7 | 22.5 | <0.0001 |

| Xpsr129 | 1 | 630.7 | 630.7 | 175.9 | <0.0001 |

| Xpsr1205 × Xabg705 | 1 | 31.1 | 31.1 | 8.6 | 0.0035 |

| Xpsr1205 × Xpsr129 | 1 | 352.1 | 352.1 | 98.2 | <0.0001 |

| Xabg705 × Xpsr129 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.6112 |

| Xpsr1205 × Xabg705 × Xpsr129 | 1 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.3894 |

| Error | 300 | 1075.6 | 3.6 |

The effects of these three QTL on mean chiasma number in Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids are summarized in Table 5. The background level of pairing in a hybrid with the a-haplotype at the Xpsr1205, Xabg705, and Xpsr129 loci was 7.0 chiasmata/cell. The average pairing in 12 hybrids (360 cells) with mean numbers of chiasmata per cell ranging from 6.8 to 7.3 was 15.7 univalents + 5.4 bivalents + 0.44 trivalents + 0.05 quadrivalents. The number of trivalents per cell ranged from 0 to 4 and the number of quadrivalents per cell ranged from 0 to 2.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of subpopulations of Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids with indicated QTL increasing homeologous chromosome pairing in hybrids relative to subpopulations devoid of all such QTL (background) or having fewer of them, and the effect of substitution of the b-haplotypes for the a-haplotypes at indicated loci on the mean chiasma number per cell in subpopulations of Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids

| QTL | No. of hybrids in smaller subpopulation | Chiasmata per cell | Compared QTL effects | QTL effect (chiasmata per cell) | Fa | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 7.0 | — | — | — | — | |

| 3S | 23 | 15.4 | 3Svs. background | 8.4 | 390.1 | <0.001 |

| 5S | 62 | 8.6 | 5Svs. background | 1.6 | 6.9 | 0.001 |

| 7S | 52 | 12.4 | 7Svs. background | 5.8 | 115.0 | <0.001 |

| 3S + 7S | 23 | 15.1 | 3S + 7S vs. 3S | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.289 |

| 3S + 5S | 15 | 15.2 | 3S + 5S vs. 3S | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.879 |

| 7S + 5S | 31 | 14.2 | 7S + 5S vs. 7S | 1.8 | 15.2 | <0.001 |

| 3S + 5S + 7S | 19 | 16.4 | 3S + 5S + 7Svs. 3S + 7S | 0.8 | 4.1 | 0.049 |

F-value from one-way ANOVA.

The chromosome 3S QTL raised the mean number of chiasmata from the background of 7.0 to 15.4. Combinations of the 3S QTL with 5S or 7S QTL had no additional effects, which is consistent with the factorial ANOVA output, indicating a strong interaction between the 3S QTL and those on 5S and 7S. In contrast, the effects of the 7S and 5S QTL were entirely additive; the mean number of chiasmata per cell increased from 12.4 to 14. 2. The 5S QTL also showed a borderline additive effect in combinations with the 3S QTL and 7S QTL, raising the mean number of chiasmata from 15.4 to 16.4/cell (Table 5).

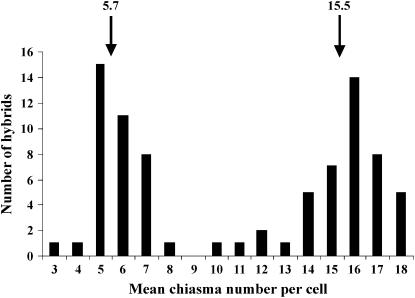

Genetic mapping:

Ae. speltoides F4 plant 125-80-13, homozygous for the low-pairing haplotypes on chromosomes 5S and 7S but heterozygous for marker loci on chromosome 3S, was crossed with Chinese Spring and the mean numbers of chiasmata per cell were determined in 67 hybrids, analyzing from two to five spikes per hybrid. The frequency distribution of mean chiasma numbers per cell was clearly bimodal among the hybrids; subpopulation means were 5.7 and 15.5 chiasmata/cell (Figure 2). While the latter mean was almost identical to the expected 15.4 chaismata (Table 5), the former mean was 1.3 chiasmata lower than the expected 7.0 chiasmata/cell for the background. This difference was attributed to the environment: the population of hybrids derived from the F4 plant 125-80-13 was grown in the summer whereas the previous population was grown in the winter. The mean phenotypic difference of 9.8 chiasmata/cell between the classes (Figure 3) made it possible to allocate each of the 67 hybrids into either the high- or the low-pairing class.

Figure 2.—

Frequency distribution of the mean number of chiasmata per cell among 67 hybrids from the cross Chinese Spring × F4 Ae. speltoides plant 125-80-13. The means of the low-homeologous-pairing and high-homeologous-pairing subpopulations are indicated.

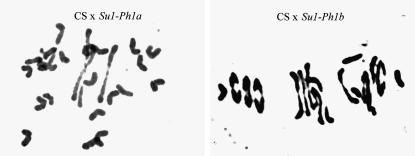

Figure 3.—

Chromosome pairing in pollen mother cells of hybrids between Chinese Spring (CS) and Ae. speltoides differing by the haplotype at the Su1-Ph1 locus.

DNAs were isolated from the 67 hybrids, and Southern blots were hybridized with 23 wheat ESTs (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/cgi-bin/westsql/map_locus.cgi) and MWG41, BCD1261, and PSR1205 clones. A genetic map of chromosome 3S was constructed. The map was 70.7 cM long and was entirely collinear with the map of the closely related Ae. tauschii chromosome 3D (not shown). The QTL completely cosegregated with Xpsr1205. Since the QTL behaved in all respects as a Mendelian locus, it was designated as Su1-Ph1 (suppressor number 1 of the Ph1 gene). Su1-Ph1b was the high-pairing haplotype.

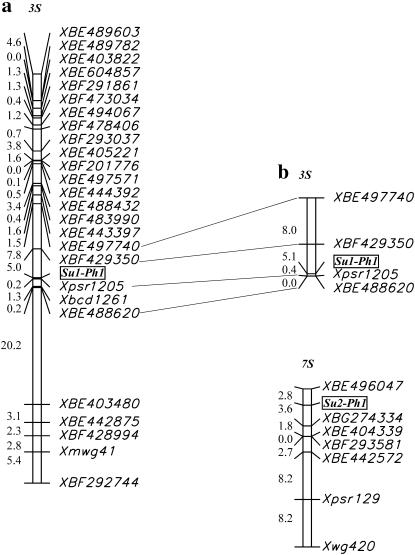

To determine the position of the Su1-Ph1 locus relative to Xpsr1205 and flanking markers, five F4 siblings of the Ae. speltoides plant 125-80-13, with the same genotype as the Ae. speltoides plant 125-80-13, were crossed with Chinese Spring and DNAs were isolated. The 266 hybrids produced were screened for recombination in the XBF497740–XBE442875 interval harboring Xpsr1205 (Figure 4) using Ae. speltoides genome-specific primers. The average number of chiasmata per cell was determined in hybrids harboring chromosomes recombined in the XBF497740–XBE442875 interval. DNAs were reisolated from the hybrids for Southern analyses. The PCR- and TaqMan-based analysis and Southern-hybridization-based analysis consistently showed that 1 of the 266 hybrids harbored a chromosome with a crossover between Su1-Ph1 and Xpsr1205. The crossover placed the Su1-Ph1 locus 0.4 cM proximal to Xpsr1205 and XBE488620 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.—

Linkage maps of Ae. speltoides chromosome 3S showing the position of the Su1-Ph1 locus (boxed) relative to EST markers (designated as BE or BF) and anonymous RFLP markers based on 67 (a) and 266 (b) Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids and the linkage map of Ae. speltoides chromosome 7S showing the position of the Su2-Ph1 locus (boxed) relative to EST markers (designated as BE, BF, and BG) and anonymous RFLP markers. Genetic distances between markers are in centimorgans and are indicated to the left of each chromosome.

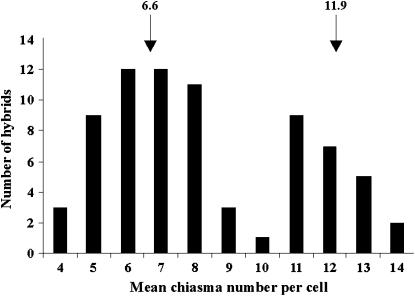

To map 7S QTL, the Ae. speltoides F4 plant 125-112-16 was crossed with Chinese Spring. The plant was homozygous for Xpsr1205a and Xabg705a and markers on the short arm of chromosome 7S but heterozygous for markers on the long arm of chromosome 7S. A total of 74 hybrids were analyzed. The frequency distribution of mean chiasma number per cell was clearly bimodal among the 74 hybrids (Figure 5). The population segregated with 31 high-pairing haplotypes to 43 low-pairing haplotypes, which is close to a 2:1 ratio rather than the expected 1:1 ratio. The most likely cause of this anomaly was segregation distortion operating against the high-pairing QTL haplotype. Segregation of the Xpsr129b and Xpsr129a haplotypes among the 315 hybrids analyzed earlier was 130:185, which does not differ from the observed segregation of the previous 74 hybrids (P = 0.98, Fisher's exact test). Taking the segregation distortion into account, the frequency distribution of pairing scores among the 74 hybrids is consistent with the segregation of a single Mendelian gene pair. We designate the locus as Su2-Ph1. Su2-Ph1b is the high-pairing haplotype. The mean chiasma number of hybrids in the low-homeologous-chromosome-pairing class was 6.6 chiasmata/cell and that of hybrids in the high-homeologous-chromosome-pairing class was 11.9 (Figure 5), both numbers being close to the expected 7.0 and 12.4 chiasmata/cell (Table 5). Recombination relative to seven molecular marker loci from the long arm of wheat chromosomes of homeologous group 7 (Dubcovsky et al. 1996; Hossain et al. 2004) was used to estimate the position of Su2-Ph1 on the Ae. speltoides genetic map. The Su2-Ph1 locus was between the EST marker loci XBE496047 and XBG274334 (Figure 4).

Figure 5.—

Frequency distribution of the mean number of chiasmata per cell among 74 hybrids from the cross Chinese Spring × F4 Ae. speltoides plant 125-112-16. The means of the low-homeologous-pairing and high-homeologous-pairing subpopulations are indicated.

The interval Xwg420–XBE496047 mapped here was previously mapped on the Ae. speltoides map based on 86 F2 plants from the 2-12-4 × PI369609-12-II cross (Luo et al. 2005). While the interval was 8.4 cM on that map, it was 27.3 cM on the map constructed here (P < 0.01). The expansion of the map constructed here occurred in all intervals that could be compared between the two maps.

DISCUSSION

Three Ae. speltoides loci controlling homeologous chromosome pairing were identified in T. aestivum × Ae. speltoides hybrids. Either individually or in various combinations, variation at these loci could elicit virtually any level of homeologous chromosome pairing between 7.0 chiasmata/cell and 16.4 chiasmata/cell in Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids, thus accounting for the variation originally described by Dvorak (1972). Two unlinked major suppressors of Ph1 were mapped on chromosomes 3S (Su1-Ph1) and 7S (Su2-Ph1) and shown to strongly interact with each other. Su1-Ph1b was fully epistatic to Su2-Ph1b. However, without knowledge of the dominance relationships between the a- and b-haplotypes, it cannot be decided what type of epistatic interaction is involved. The expression of Su1-Ph1 and Su2-Ph1 is not equivalent: Su1-Ph1 is a stronger suppressor than Su2-Ph1. Therefore, the Su1-Ph1 and Su2-Ph1 dihybrid would produce three hybrid classes rather than the two expected for duplicate gene interaction. Nevertheless, it is likely that the action of the two genes is closely related at the molecular level and that the genes may even have originated by duplication of a single ancestral locus.

The discovery of a QTL on chromosome 5S with a minor effect provides evidence for the existence of a system of minor genes affecting homeologous chromosome pairing in the Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids predicted by Chen and Dvorak (1984). Following the rules of wheat QTL nomenclature, we designate this QTL as QPh.ucd-5S (chromosome 5S QTL affecting pairing of homeologous chromosomes). QPh.ucd-5Sb is the high-pairing haplotype of the QTL. QPh.ucd-5S is located in the low-recombination region of chromosome 5S. The lack of recombination of molecular markers in that region makes the location of QPh.ucd-5S uncertain. The effects of the QTL peaked near the Xabg705 and Xpsr628 loci, both in the short arm of wheat chromosomes of homeologous group 5 (Gale et al. 1993; Dubcovsky et al. 1996). The expression of QPh.ucd-5S is additive to Su2-Ph1 and under some circumstances also to Su1-Ph1. The latter is observed in the enhancement of homeologous pairing from 15.1 to 16.4 chiasmata/cell in Chinese Spring × Ae. speltoides hybrids due to the addition of QPh.ucd-5Sb to Su1-Ph1b and Su2-Ph1b.

The QPh.ucd-5S could correspond to the homeologous chromosome pairing promoting locus on the short arms of wheat chromosomes 5A, 5B, and 5D (Riley and Chapman 1967; Dvorak 1976; Cuadrado et al. 1991) and on the Lophopyrum elongatum chromosome 5E (Dvorak 1987). Promotion of homeologous chromosome pairing by these loci was suggested by the observation that the level of homeologous chromosome pairing was reduced if the short arm of 5A, 5B, or 5D was absent from hybrids or haploids. However, the genes were shown to be essential for crossing over between homologous chromosomes and their primary role is very likely controlling the recombination between homologous chromosomes (Kota and Dvorak 1986). They show additive effects and an increase in their dose results in an increase in homeologous chromosome pairing and partial suppression of Ph1 (Dvorak 1987). This expression pattern parallels the additive effects of QPh.ucd-5S. On the basis of interactions among the three loci discovered here, we hypothesize that Su1-Ph1 and Su2-Ph1 act on Ph1 whereas QPh.ucd-5S affects recombination between homologous chromosomes and acts independently of the Ph1 mechanism.

Comparative sequencing of the wheat Ph1 region led Griffiths et al. (2006) to the hypothesis that an insertion of heterochromatic sequence from chromosome 3A into the cdc2-4 gene in the cdc2 multigene locus on chromosome 5B is synonymous with Ph1. The Ph1 gene is completely dominant. Its deletion results in the restoration of the default state, which is the presence of homeologous chromosome pairing. That makes it unlikely that the genetic event that produced Ph1 was a loss-of-function mutation and poses difficulties with the hypothesis that the cdc2-4 pseudogene is synonymous with Ph1. The cdc2 multigene locus is almost certainly present on chromosome 5S since no translocation involving the long arm of Ae. speltoides chromosome 5S was detected in comparative mapping of the Ae. speltoides genome (Luo et al. 2005). Yet the long arm of chromosome 5S had no effect on Ph1 activity. These arguments suggest that Ph1 is an active gene rather than a pseudogene.

In addition to Ae. speltoides, Ae. mutica is the only other species possessing genes that fully suppress the Ph1 activity (Dover and Riley 1972). The Ph1 suppression in Ae. mutica is also controlled by two major genes (Dover and Riley 1972). Although the chromosomal location of the Ae. mutica suppressors is unknown, it is possible that they correspond to Su1-Ph1 and Su2-Ph1.

The Ph1 locus prevents recombination between homeologous chromosomes in wheat and is thus a powerful barrier to introgression of alien genes from wheat relatives into wheat and their exploitation for wheat improvement. Incorporation of a Ph1 suppressor into wheat would greatly facilitate introgression of alien genes into wheat chromosomes via recombination between homeologous chromosomes. To accomplish this goal, Chen et al. (1994) twice backcrossed Ae. speltoides to wheat and developed a wheat line showing a partial suppression of Ph1. The gene was named PhI (inhibitor of Ph). It was suggested that it was introgressed into wheat chromosome 4D, presumably via a crossover between homeologous chromosomes 4D and 4S. Weak expression of PhI and our failure to map any of the major Ph1 suppressors on chromosome 4S suggests that PhI corresponds to neither Su1-Ph1 nor Su2-Ph1. The presence of multivalents in hybrids with the background level of chromosome pairing strongly suggests that Ph1 was partially suppressed even at the background level in our study and that the PhI could possibly be a locus that we failed to detect. Chromosomal mapping of the PhI gene was based on indirect evidence, and the possibility that the gene actually corresponds to a weaker allele at either the Su1-Ph1 or the Su2-Ph1 locus should not be entirely dismissed.

Of the three loci discovered here, Su1-Ph1 is the logical target for introgression into wheat and manipulation of homeologous recombination in wheat. Since the gene is epistatic to Su2-Ph1, no advantage would be gained by combining Su1-Ph1 with Su2-Ph1. The Su1-Ph1 gene is located in the distal region of chromosome 3S that is collinear with wheat chromosome 3B (Luo et al. 2005). The identification of molecular markers tightly linked to Su1-Ph1 and the development of Ae. speltoides genome-specific PCR primers for the detection of Ae. speltoides markers in the wheat genetic background accomplished here will greatly facilitate the detection of Su1-Ph1 during the backcrossing of Ae. speltoides into wheat.

The mechanism of the localization of crossovers in short distal regions of Ae. speltoides chromosomes (Luo et al. 2005) is currently unknown. The observation that a family of hybrids derived from an Ae. speltoides F4 plant showed a dramatic increase in recombination in the proximal region compared to that observed in the F2 generation from the same cross suggests that genetic variation may exist in material developed in this project, which could be exploited in genetic characterization of the mechanism controlling crossover localization in Ae. speltoides.

Acknowledgments

We thank O. D. Anderson, M. D. Gale, A. Graner, B. S. Gill, G. E. Hart, A. Kleinhofs, and M. E. Sorrells for sharing clones with us and the U. S. Department of Agriculture/Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service/National Research Initiative for financial support by grant 2001-35301-10594 to J. Dvorak and M.-C. Luo.

References

- Allard, R. W., 1956. Formulas and tables to facilitate the calculation of recombination values in heredity. Hilgardia 24: 235–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K. C., and J. Dvorak, 1984. The inheritance of genetic variation in Triticum speltoides affecting heterogenetic chromosome pairing in hybrids with Triticum aestivum. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 26: 279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. D., H. Tsujimoto and B. S. Gill, 1994. Transfer of PhI genes promoting homoeologous pairing from Triticum speltoides to common wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 88: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado, C., C. Romero and J. R. Lacadena, 1991. Meiotic pairing control in wheat-rye hybrids.1. Effect of different wheat chromosome arms of homoeologous group-3 and group-5. Genome 34: 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dover, G. A., and R. Riley, 1972. Variation at two loci affecting homeologous meiotic chromosome pairing in Triticum aestivum × Aegilops mutica hybrids. Nature New Biol. 235: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dover, G., and R. Riley, 1977. Inferences from genetical evidence on the course of meiotic chromosome pairing in plants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 277: 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubcovsky, J., M. C. Luo, G. Y. Zhong, R. Bransteitter, A. Desai et al., 1996. Genetic map of diploid wheat, Triticum monococcum L., and its comparison with maps of Hordeum vulgare L. Genetics 143: 983–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J., 1972. Genetic variability in Aegilops speltoides affecting homoeologous pairing in wheat. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 14: 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J., 1976. The relationship between the genome of Triticum urartu and the A and B genomes of T. aestivum. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 18: 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J., 1987. Chromosomal distribution of genes in Elytrigia elongata which promote or suppress pairing of wheat homoeologous chromosomes. Genome 29: 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J., 1998. Genome analysis in the Triticum-Aegilops alliance, pp. 8–11 in 9th International Wheat Genetics Symposium, edited by A. E. Slinkard. University Extension Press, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

- Dvorak, J., and H. B. Zhang, 1990. Variation in repeated nucleotide sequences sheds light on the phylogeny of the wheat B and G genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 9640–9644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J., P. E. McGuire and B. Cassidy, 1988. Apparent sources of the A genomes of wheats inferred from the polymorphism in abundance and restriction fragment length of repeated nucleotide sequences. Genome 30: 680–689. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J., Z.-L. Yang, F. M. You and M. C. Luo, 2004. Deletion polymorphism in wheat chromosome regions with contrasting recombination rates. Genetics 168: 1665–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M., and T. Mello-Sampayo, 1967. Suppression of homeologous pairing in hybrids of polyploid wheats × Triticum speltoides. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 9: 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Friebe, B., L. L. Qi, S. Nasuda, P. Zhang, N. A. Tuleen et al., 2000. Development of a complete set of Triticum aestivum-Aegilops speltoides chromosome addition lines. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101: 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, M. D., M. D. Atkinson, C. N. Chinoy, R. L. Harcourt, J. Jia et al., 1993. Genetic maps of hexaploid wheat, pp. 29–40 in 8th International Genetic Symposium, edited by Z. S. Li and Z. Y. Xin. China Agricultural Scientech Press, Beijing.

- Griffiths, S., R. Sharp, T. N. Foote, I. Bertin, M. Wanous et al., 2006. Molecular characterization of Ph1 as a major chromosome pairing locus in polyploid wheat. Nature 439: 749–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, K. G., V. Kalavacharla, G. R. Lazo, J. Hegstad, M. J. Wentz et al., 2004. A chromosome bin map of 2148 expressed sequence tag loci of wheat homoeologous group 7. Genetics 168: 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber, G., and R. S. Athwal, 1972. A reassessment of the course of evolution of wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 69: 912–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosambi, D. D., 1943. The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann. Eugen. 12: 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kota, R. S., and J. Dvorak, 1986. Mapping of a chromosome pairing gene and 5SrRNA genes in Triticum aestivum L. by a spontaneous deletion in chromosome arm 5Bp. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 28: 266–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, S., M. Daly and E. Lander, 1992. Whitehead Institute Technical Report, Ed. 3. Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA.

- Luo, M. C., K. R. Deal, Z. L. Young and J. Dvorak, 2005. Comparative genetic maps reveal extreme crossover localization in the Aegilops speltoides chromosomes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111: 1098–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, M., 1957. Asynaptic effect of chromosome V. Wheat Inf. Serv. 5: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, R., 1960. The diploidization of polyploid wheat. Heredity 15: 407–429. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, R., and V. Chapman, 1958. Genetic control of the cytologically diploid behaviour of hexaploid wheat. Nature 182: 713–715. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, R., and V. Chapman, 1967. Effects of 5Bs in suppressing the expression of altered dosage of 5BL on meiotic chromosome pairing in Triticum aestivum. Nature 216: 60–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, P., and G. L. Stebbins, 1956. Morphological evidence concerning the origin of the B genome in wheat. Am. J. Bot. 43: 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, E. R., and M. Okamoto, 1958. Intergenomic chromosome relationships in hexaploid wheat. Proceedings of the X International Congress of Genetics, McGill University, Montreal, pp. 258–259.