Abstract

Upc2p and Ecm22p are a pair of transcription factors responsible for the basal and induced expression of genes encoding enzymes of ergosterol biosynthesis in yeast (ERG genes). Upc2p plays a second role as a regulator of hypoxically expressed genes. Both sterols and heme depend upon molecular oxygen for their synthesis, and thus the levels of both have the potential to act as indicators of the oxygen environment of cells. Hap1p is a heme-dependent transcription factor that both Upc2 and Ecm22p depend upon for basal level expression of ERG genes. However, induction of both ERG genes and the hypoxically expressed DAN/TIR genes by Upc2p and Ecm22p occurred in response to sterol depletion rather than to heme depletion. Indeed, upon sterol depletion, Upc2p no longer required Hap1p to activate ERG genes. Mot3p, a broadly acting repressor/activator protein, was previously shown to repress ERG gene expression, but the mechanism was unclear. We established that Mot3p bound directly to Ecm22p and repressed Ecm22p- but not Upc2p-mediated gene induction.

TRANSCRIPTIONAL regulation of cholesterol synthesis in mammalian cells involves regulated proteolysis and the liberation of transcription factors from membrane tethers (Goldstein et al. 2002). A similar regulatory scheme, including SREBP and SCAP orthologs, is found in fission yeast (Hughes et al. 2005). Budding yeast lacks orthologs of the mammalian regulators. Regulation of ergosterol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae has both intrinsic and practical interest as this pathway contains the targets of most antifungal drugs. Genes encoding enzymes of ergosterol biosynthesis are transcriptionally regulated in response to the need for ergosterol (Arthington-Skaggs et al. 1996; Dimster-Denk and Rine 1996; Smith et al. 1996; Kennedy et al. 1999) but in ways that differ markedly from the regulation of the corresponding genes in mammals (Dimster-Denk and Rine 1996; Davies et al. 2005).

Upc2p and Ecm22p, two transcription factors with similar sequences, bind a sequence motif known as the sterol regulatory element (SRE) and regulate the ergosterol biosynthetic genes ERG1, ERG2, ERG3, ERG7, ERG25, ERG26, and ERG27 (Vik and Rine 2001; Germann et al. 2005). Although binding of Upc2p and Ecm22p at other ERG genes has not been tested directly, the SRE binding site is found in many of these genes, suggesting that these two proteins are major regulators of ergosterol biosynthesis.

In addition to binding the promoters of ERG genes, Upc2p binds a similar sequence in the regulatory region of hypoxically induced mannoprotein-encoding genes known as the DAN/TIR genes (Abramova et al. 2001a,b). These genes are responsible for changes in the cell wall of yeast grown hypoxically. Upc2p has also been implicated in the uptake of sterols under hypoxic conditions (Lewis et al. 1988; Crowley et al. 1998; Wilcox et al. 2002; Alimardani et al. 2004). Normally, yeast cells take up sterols from their environment only under hypoxic conditions (Andreasen and Stier 1953), but an overactive allele of UPC2, UPC2-1, allows aerobic uptake of sterols (Lewis et al. 1988). Moreover, nearly one-third of hypoxically induced genes contain at least one potential Upc2p/Ecm22p binding site (Kwast et al. 2002). These observations suggest that Upc2p, and perhaps Ecm22p, are major factors in the adaptation to hypoxia.

Upc2p and Ecm22p share similar binuclear cluster DNA binding domains (70% identical in sequence) and similar activation/regulatory domains (76% identical in sequence), but Upc2p and Ecm22p function at different times. Ecm22p is more abundant at ERG promoters under normal laboratory growth conditions. However, when sterols are depleted, Ecm22p levels drop and Upc2p replaces Ecm22p at the promoters of ERG genes (Davies et al. 2005). Such an activator switch implies that there must be other factors that regulate the activation, abundance, and localization of Upc2p and Ecm22p, as well as conditions that favor the use of one activator over the other.

Other transcription factors also participate in the regulation of ergosterol biosynthesis genes. Hap1p, a heme-activated transcriptional regulator, regulates HMG1 (Thorsness et al. 1989), the structural gene for 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase. A HAP1 mutant allele can cause lower expression in several ergosterol biosynthetic genes with a corresponding reduction in ergosterol levels (Tamura et al. 2004). Yer064Cp, a nuclear protein of unknown function, is important for the activation of some ERG genes (Kennedy et al. 1999; Germann et al. 2005). Finally, deletion of MOT3, a zinc-finger protein that can act as both a transcriptional activator and a repressor, leads to increased expression of ERG2, ERG6, and ERG9 (Hongay et al. 2002).

In this study, we established the functions of Hap1p and Mot3p in regulating the gene targets of Upc2p and Ecm22p. In addition we tested the hypothesis that sterol, not heme, depletion was the signal responsible for hypoxic activation of Upc2p and Ecm22p and uncovered unanticipated complexity in how oxygen levels affect the expression of Upc2 and Ecm22p gene targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media:

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were isogenic with W303 except BY4741 and JR8037 (the W303/BY4741 diploid). Gene deletions were made by a PCR-based gene disruption method (Burke et al. 2000) such that the entire open reading frame (ORF) was replaced by the NATMX4 (nourseothricin resistance) gene amplified from pAG25 or the HPHMX4 (hygromycin B resistance) gene amplified from pAG32 (Goldstein and McCusker 1999). Sequences encoding the TAP-tag (Rigaut et al. 1999) or the FLAG-tag (Gelbart et al. 2001) were integrated in frame at the 3′ end of the ORFs using homologous recombination and one-step gene integration of PCR-amplified modules.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1a | MATaade2-1 leu2-3,112 his3-1 ura3-52 trp1-100 can1-100 | R. Rothstein |

| BY4742 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Brachmann et al. (1998) |

| JRY7179 | W303-1a upc2Δ∷HIS3 | Vik and Rine (2001) |

| JRY7180 | W303-1a ecm22Δ∷TRP1 | Vik and Rine (2001) |

| JRY7181 | W303-1a ecm22Δ∷TRP1 upc2Δ∷HIS3 | Vik and Rine (2001) |

| JRY7865 | W303 UPC2-TAP (TRP1) | Davies et al. (2005) |

| JRY7866 | W303 ECM22-TAP (TRP1) | Davies et al. (2005) |

| JRY8037 | Resulting diploid of W303-1a and BY4742 cross | |

| JRY8038 | W303-1a hap1Δ∷NatMX4 | |

| JRY8040 | W303-1a hap1Δ∷NatMX4 upc2Δ∷HIS3 | |

| JRY8042 | W303-1a hap1Δ∷NatMX4 ecm22Δ∷TRP1 | |

| JRY8044 | W303-1a mot3Δ∷HghMX4 | |

| JRY8048 | W303-1a mot3Δ∷HghMX4 upc2Δ∷HIS3 | |

| JRY8050 | W303-1a mot3Δ∷HghMX4 ecm22Δ∷TRP1 | |

| JRY8056 | W303-1a mot3Δ∷HghMX4 upc2Δ∷HIS3 ecm22Δ∷TRP1 | |

| JRY8062 | W303-1a hap1Δ∷NatMX4 UPC2-TAP (TRP1) | |

| JRY8068 | W303-1a hap1Δ∷NatMX4 ECM22-TAP (TRP1) | |

| JRY8072 | W303-1a mot3Δ∷HghMX4 UPC2-TAP (TRP1) | |

| JRY8076 | W303-1a mot3Δ∷HghMX4 ECM22-TAP (TRP1) | |

| JRY8082 | W303-1a HAP1-flag (KanMX4) | |

| JRY8084 | W303-1a HAP1-flag (KanMX4) ECM22-TAP (TRP1) | |

| JRY8085 | W303-1a MOT3-flag (KanMX4) | |

| JRY8087 | W303-1a MOT3-flag (KanMX4) ECM22-TAP (TRP1) | |

| JRY8088 | W303-1a UPC2-flag (KanMX4) | |

| JRY8089 | W303-1a UPC2-flag (KanMX4) ECM22-TAP (TRP1) | |

| JRY8090 | W303-1a ECM22-flag (KanMX4) |

Unless otherwise indicated, all strains were generated for this study.

All yeast strains were grown in complete synthetic medium [0.67% Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, complete supplemental mixture minus appropriate amino acids (Q-Biogene)] containing 2% glucose, except for the experiment presented in Figure 5, in which strains were grown in YPD. A 25 mg/ml stock solution of lovastatin (a generous gift from James Bergstrom) was prepared as previously described (Dimster-Denk et al. 1994). Lovastatin was added to liquid media to a final concentration of 30 μg/ml unless otherwise noted. Hemin (Sigma) was added from a 4 mg/ml stock (50% ethanol, 20 mm sodium hydroxide) to a final concentration of 40 μg/ml. Ketoconazole (Sigma) was added from a 10 mg/ml (DMSO) stock to a final concentration of 25 μg/ml. For hypoxic growth, cells were grown in tightly capped 50 ml flasks without shaking at 30°. Induction of DAN1, TIR1, ANB1, and COX5b in cells grown this way verified these conditions as hypoxic.

Figure 5.—

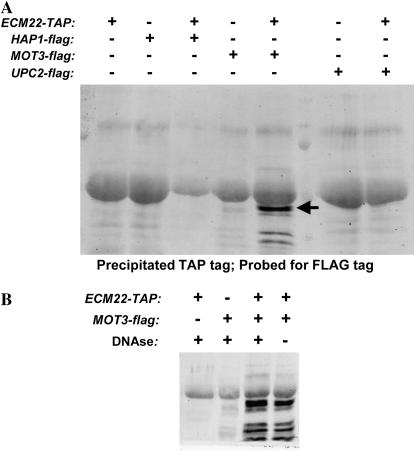

Mot3p physically interacted with Ecm22p. Strains containing the indicated tagged proteins were precipitated with IgG beads to pull down TAP-tagged Ecm22p as outlined in materials and methods. The precipitate was then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-flag antibody. (A) Arrow indicated MOT3-flag specific band. (B) The indicated samples were treated with DNAse prior to precipitation with IgG.

Plasmids:

pJR2316 was a pERG2:lacZ reporter described previously (Vik and Rine 2001).

Genotyping of HAP1 allele:

Yeast spores were subjected to colony PCR with the primers bd194 (5′-GGAGCTGGAACTGCGAATAC-3′), bd195 (5′-CATTTGCGTCATCTTCTAACACCG-3′), and bd196 (5′-CTCCCATATTGGAAAATCTGCTC-3′). In the presence of wild-type HAP1, bd194 and bd196 amplify a 250-bp product. In the presence of the S288C HAP1 mutation, bd194 and bd195 amplify a 350-bp product.

β-Galactosidase assays:

β-Galactosidase assays were performed essentially as previously described (Burke et al. 2000).

Analysis of protein levels:

Strains were grown to midlog phase and whole-cell extracts were prepared as described previously (Foiani et al. 1994). Extracts were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. FLAG-tagged proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-flag (rabbit or mouse; Sigma). TAP-tagged proteins were immunoblotted with an anti-flag antibody (rabbit; Sigma) to detect the TAP tag. All immunoblots were also blotted with anti-3-phosphoglycerate kinase antibodies (Molecular Probes) as a loading control. Immunoblots were scanned using the Li-Cor Odyssey imaging system.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation:

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (Davies et al. 2005). For TAP-tagged proteins (Figures 2 and 4), immunoprecipitations were performed using 30 μl IgG sepharose (Amersham Biosciences). For Hap1-flag (Figure 2), immunoprecipitations were performed using 25 μl anti-flag M2-agarose (Sigma). Typically, IPs were performed overnight at 4°. DNA enrichment was analyzed by real-time PCR and Syber-Green fluorescence on a Stratagene MX3000 real-time PCR instrument. Real-time PCR was performed using primers to the ERG3 promoter (5′-GACGCCTTTTGTTGCGATTGTCG-3′ and 5′-CAGCAACAACAATACCCGATCGC-3′) and to ACT1 (5′-GGCATCATACCTTCTACAACGAATTG-3′ and 5′-CTACCGGAAGAGTACAAGGACAAAAC-3′) with DNA derived from whole-cell extracts as a standard.

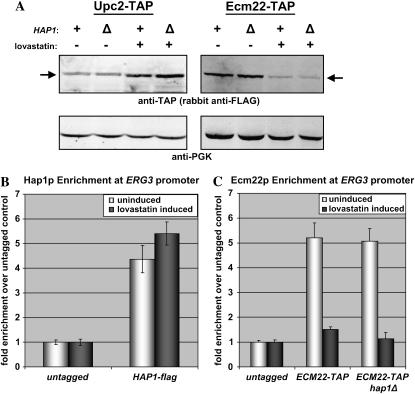

Figure 2.—

(A) Levels of Upc2p and Ecm22p were unaffected by deletion of HAP1. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from JRY7865 (UPC2-TAP), JRY8062 (UPC2-TAP hap1Δ), JRY7866 (ECM22-TAP), and JRY8068 (ECM22-TAP hap1Δ) grown in the presence or absence of 30 μg/ml lovastatin. Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in materials and methods. Arrows indicate tagged proteins. (B). Hap1 was enriched at the ERG3 promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed using untagged and HAP1-flag tagged strains as described in materials and methods. Real-time PCR was used to quantify the levels of ERG3 promoter DNA and ACT1 control DNA. The ratio of ERG3 promoter DNA to ACT1 DNA was calculated for each sample. Bars are the average of three reactions and indicated the fold enrichment of Hap1-flag experiments over the untagged control. (C) Deletion of HAP1 has no affect on the levels of Ecm22p at the ERG3 promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed using untagged and ECM22-TAP tagged strains as described in materials and methods. Experiments were analyzed using real-time PCR as described in B.

Figure 4.—

(A) Deletion of MOT3 does not significantly affect Upc2p levels, but does result in higher Ecm22p levels following sterol depletion. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from JRY7865 (UPC2-TAP), JRY8072 (UPC2-TAP mot3Δ), JRY7866 (ECM22-TAP), and JRY8076 (ECM22-TAP mot3Δ) grown in the presence or absence of 30 μg/ml lovastatin. Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in materials and methods. Ecm22p levels were quantified using the Li-Cor Odyssey imaging system and are normalized to the level of Ecm22p in uninduced wild type. Arrows indicate tagged proteins. (B) Deletion of MOT3 led to increased promoter occupancy of Ecm22p following sterol depletion. Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed using untagged, ECM22-TAP tagged, and ECM22-TAP mot3Δ strains as described in materials and methods. Real-time PCR was used to quantify the levels of ERG3 promoter DNA and ACT1 control DNA. The ratio of ERG3 promoter DNA to ACT1 DNA was calculated for each sample. Bars are the average of three reactions and indicate the fold enrichment of Ecm22p-TAP experiments over the untagged control.

Affinity purification using TAP-tagged proteins:

Co-immunoprecipitations were performed essentially as described previously (Kobor et al. 2004), except that the DNAse-treated samples identified in Figure 5 were treated with DNAse as described previously (Watson et al. 2000). Samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-flag antibody (Sigma). Immunoblots were scanned using the Li-Cor Odyssey imaging system.

Analysis of gene expression:

Gene expression was measured using quantitative RT–PCR. RNA was prepared as described previously (Schmitt et al. 1990). RNA preps were digested with RNase-free DNase I (Roche and QIAGEN) and cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system for RT–PCR (Invitrogen) and oligo(dT). cDNA was analyzed by real-time PCR and Syber-Green fluorescence on a Stratagene MX3000 real-time PCR instrument. Samples were analyzed in triplicate for each of two independent RNA preparations. cDNA from ACT1 was used as a loading control. Primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/.

RESULTS

In this study we explored the mechanism by which the Upc2p and Ecm22p transcription factors regulate ERG genes. This issue has been complicated by the apparently conflicting results from different studies, by influences of additional regulators whose function is not known, and by ambiguity as to the physiological signal(s) that regulate the activity of Upc2 and Ecm22p. We first establish the genetic basis for some, if not most, of the conflicting data and then move on to clarify the remaining issues.

HAP1—the genetic basis of strain differences in ERG2 expression:

To find proteins that, in conjunction with Upc2p and Ecm22p, contribute to the regulation of ERG genes, a genetic screen was designed using a pERG2∷lacZ reporter plasmid (pJR2316) and the yeast deletion collection (Research Genetics). The plan was to transform the knockout collection with the reporter plasmid and screen for either increased or decreased ERG2 expression compared with the parent strain. However, when ERG2 expression was tested in BY4742, the parent strain of the MATα deletion collection, we found that expression was fivefold lower than what had been observed previously in W303-derived strains (Vik and Rine 2001; Davies et al. 2005). A hybrid diploid formed between the two strains exhibited an intermediate level of ERG2∷lacZ expression (Figure 1A).

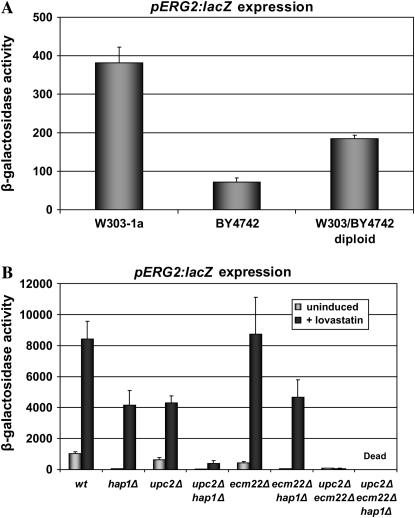

Figure 1.—

(A) ERG2 expression was impaired in BY4742, a parent strain for the deletion collection. W303-1a, BY4742, and the diploid strain resulting from the cross of the two (JRY8037) were transformed with a pERG2∷lacZ reporter (pJR2316). Extracts from these strains were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in materials and methods. (B) Uninduced ERG2 expression depended on Hap1p, as did Ecm22p-mediated ERG2 induction following sterol depletion. Wild-type W303, hap1Δ (JRY8038), upc2Δ (JRY7179), upc2Δhap1Δ (JRY8040), ecm22Δ (JRY7180), ecm22Δhap1Δ (JRY8042), and upc2Δecm22Δ (JRY7181) strains were transformed with a pERG2∷lacZ reporter (pJR2316). Strains were grown in the presence or absence of 30 μg/ml lovastatin. Extracts prepared from these cultures were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in materials and methods.

The difference in ERG2 expression between W303 and BY4742 could have been due to variation at a single locus or the composite effect of strain differences at multiple loci. If the differences in ERG2 expression were the result of a single Mendelian locus, high and low ERG2 expression levels would be expected to segregate 2:2 when these two strains were crossed and sporulated. Therefore, the W303/BY4742 diploid was sporulated and the resulting tetrads tested for ERG2 expression. For each of four tetrads, two spores had high ERG2 expression, similar to that observed in W303, and two had low ERG2 expression, similar to that observed in BY4742 (data not shown), indicating that the difference in ERG2 expression mapped to a single locus.

Prior to initiating mapping of the locus responsible for this difference, we tested whether known differences between these two strains could account for the difference in ERG2 expression. Strains derived from S288c (such as BY4742) have mutant forms of several genes including a mutant allele of HAP1, which encodes a heme-responsive transcriptional regulator (Gaisne et al. 1999). This mutation, caused by an insertion near the 3′ end of the HAP1 ORF, has a detrimental effect on some, but not all, Hap1p targets (Gaisne et al. 1999). Several observations suggested that HAP1 may be the basis of the difference in ERG2 expression in these two strains: Deletion of both UPC2 and ECM22 results in lethality in S288C (Shianna et al. 2001) but not in W303 (Vik and Rine 2001). The lethality of the upc2 ecm22 double null mutation in S288c appears to result from the hap1 mutant allele, as restoration of the wild-type HAP1 restores viability (M. Valachovic, personal communication). Moreover, deletion of UPC2, ECM22, and HAP1 results in lethality in W303 (data not shown). The haploid progeny from the W303/BY4742 diploid were therefore tested for the S288c allele of HAP1. In every case tested, spores with low ERG2 expression had the S288c-derived mutant allele of HAP1 and spores with high expression had the W303-derived allele, indicating that low ERG2 expression was a result of the mutant allele of HAP1 (data not shown).

Upc2p and Ecm22p had different requirements for Hap1p:

To examine the role of Hap1p in the regulation of ERG genes, especially with respect to Upc2p and Ecm22p, hap1Δ (JRY8038), hap1Δupc2Δ (JRY8040), and hap1Δecm22Δ (JRY8042) derivatives of W303 were tested for ERG2 expression in both the presence and the absence of lovastatin, an inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase, which catalyzes an early step in sterol biosynthesis. Thus the presence or absence of lovastatin corresponds to inducing and noninducing conditions, respectively. Under noninducing conditions, ERG2 expression was profoundly reduced in all strains lacking HAP1 (Figure 1B, shaded bars). Thus, Hap1p was required for the basal expression of ERG2, regardless of whether that expression was activated by Ecm22p or Upc2p.

Unlike the upc2Δecm22Δ double mutant strain, however, a strain without HAP1 was able to induce ERG2 expression when sterols were depleted by growth in the presence of lovastatin, albeit to a lower level (Figure 1B, solid bars). Induction in the absence of HAP1 depended mostly on Upc2p, as very little induction was observed in a strain when both UPC2 and HAP1 were deleted. Thus, upon inducing conditions, Upc2p could activate ERG2 expression in a Hap1-independent manner, whereas Ecm22p was a Hap1p-dependent activator of ERG2 expression.

Hap1p acted at ERG promoters:

There are several possible ways that Hap1p could regulate Ecm22p and, to a lesser extent, Upc2p at ERG promoters. Hap1p might modulate ERG gene expression indirectly either by regulating transcription of UPC2 and ECM22 or by regulating the stability of Upc2p and Ecm22p. Alternatively, Hap1p might act more directly to influence either the binding of Upc2p and Ecm22p at ERG promoters or the activity of these two proteins once bound. To distinguish among these possibilities, the levels of Upc2p and Ecm22p were measured in a hap1Δ strain grown in the presence or absence of lovastatin. Neither Upc2p nor Ecm22p levels were affected by the deletion of HAP1, under inducing or noninducing conditions (Figure 2A). Similarly, Hap1p levels were unaffected by lovastatin treatment (data not shown). The increase in Upc2p and decrease in Ecm22p evident upon induction were described previously (Davies et al. 2005). These data argued for a direct mechanism of Hap1 function.

To determine if Hap1p acted directly on ERG gene promoters, a flag-tagged version of Hap1p was used for chromatin-immunoprecipitation experiments. The tagged version of Hap1p complemented the hap1 null mutation with respect to ERG2 expression (data not shown). As chromatin immunoprecipitation of ERG2, with its single SRE, has proven difficult (data not shown) and regulation of ERG3 parallels regulation of ERG2 (Vik and Rine 2001), Hap1p and Ecm22p were tested for their enrichment at the ERG3 promoter, which contains five SREs. Hap1p was enriched at the ERG3 promoter and to approximately the same extent under inducing and noninducing conditions (Figure 2B). Although Hap1p was at the ERG3 promoter, deletion of HAP1 had no effect on the presence of Ecm22p at the same promoter in cells grown in either the presence or the absence of lovastatin (Figure 2C). Thus, Hap1p influenced the activity, but not the presence, of Ecm22p at ERG promoters.

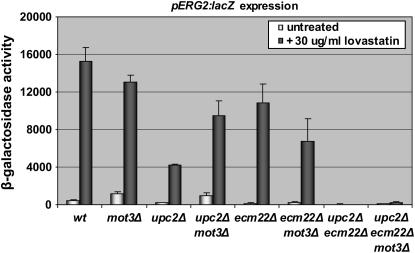

Mot3p inhibited Ecm22p:

Mot3p, a dose-dependent repressor/activator, represses expression of several ERG genes including ERG2 (Hongay et al. 2002), although the mechanism was unknown. To determine whether Mot3p acted through Upc2p, Ecm22p, or by some independent mechanism, mot3Δ (JRY8044), mot3Δupc2Δ (JRY8048), mot3Δecm22Δ (JRY8050), and mot3Δupc2Δecm22Δ (JRY8056) deletion strains were constructed and tested for ERG2 expression. As reported by Hongay et al. (2002), the deletion of MOT3 led to an increase in basal ERG2 expression (Figure 3, first two shaded bars). The increase in ERG2 expression depended primarily on Ecm22p, as the deletion of MOT3 had no significant effect on ERG2 activation by Upc2p (Figure 3). The activation of ERG2 by Ecm22p was increased in a mot3Δ strain in both inducing and noninducing conditions (Figure 3, compare upc2Δ to upc2Δmot3Δ). Thus, Mot3p repressed Ecm22p-dependent expression of ERG2 but not Upc2-dependent expression. It is important to note that induction of ERG2 by Ecm22p in response to sterol depletion was not due simply to relief of Mot3p repression, as considerable ERG2 induction was still evident in a mot3 mutant.

Figure 3.—

Mot3p inhibited Ecm22p. Wild-type W303, mot3Δ (JRY8044), upc2Δ (JRY7179), upc2Δmot3Δ (JRY8048), ecm22Δ (JRY7180), ecm22Δmot3Δ (JRY8050), upc2Δecm22Δ (JRY7181), and upc2Δecm22Δmot3Δ (JRY8056) strains were transformed with a pERG2∷lacZ reporter (pJR2316). Strains were grown in the presence or absence of 30 μg/ml lovastatin. Extracts prepared from these cultures were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in materials and methods.

Upon sterol depletion, reduction of Ecm22p levels was partially blocked in a mot3Δ strain:

In cells treated with lovastatin to deplete sterols, the level of Ecm22p decreases to about one-third the level observed in noninduced cells, whereas the level of Upc2p increases about fourfold (Davies et al. 2005). To determine whether the deletion of MOT3 affected Ecm22p or Upc2p levels, Ecm22p-TAP and Upc2p-TAP levels were measured in a mot3Δ strain. Deletion of MOT3 had little, if any, effect on Upc2p levels. However, upon sterol depletion, the level of Ecm22p was approximately twofold higher in mot3Δ strains (Figure 4A), which corresponded quantitatively to the twofold greater ERG2 induction by Ecm22p in mot3Δ strains (Figure 3). A similar pattern was observed when the enrichment of Ecm22p at the ERG3 promoter was tested using chromatin immunoprecipitation in a mot3Δ strain (Figure 4B). Thus, Mot3p caused at least part of the reduction in overall Ecm22p levels under inducing conditions, and at least part of the reduction in SRE occupancy at the ERG3 promoter.

Mot3p interacted directly with Ecm22p:

To test whether Mot3p affects Ecm22p by direct physical interaction, TAP-tagged Ecm22p was immunoprecipitated from cells with FLAG-tagged Hap1p, Mot3p, or Upc2p and then immunoblotted with an anti-FLAG antibody. These experiments revealed a strong and specific interaction between Ecm22p and Mot3p (Figure 5A). Adding a DNAse digestion prior to precipitation had no effect on this interaction, thus precluding a DNA bridge between two proteins binding at the same promoter as an explanation (Figure 5B). It should be noted that the observed band did not correspond to full-length Mot3p, but did correspond to the major MOT3-flag-specific band observed in whole-cell extracts (data not shown). Thus a major mechanism for the repression of ERG gene expression by Mot3p was by direct binding to the Ecm22p activator.

Testing the role of heme A in ERG gene expression:

As lovastatin inhibits an early step in ergosterol biosynthesis, it reduces not only the synthesis of ergosterol, but also the synthesis of certain nonsterol products, such as heme A. Heme A, a farnesylated version of heme, is an essential prosthetic group of cytochrome C oxidase (Moraes et al. 2004). Because cytochrome C oxidase is thought to play a role in oxygen sensing and the activation of some hypoxically expressed genes (Kwast et al. 1999), in principle, depletion of heme A by lovastatin might result in a hypoxic response. Thus, depletion of heme A, rather than sterol depletion per se, might be responsible for the switch from Ecm22p to Upc2p at ERG promoters under inducing conditions. Such a model would be consistent with Upc2p's role in activating the hypoxically expressed DAN/TIR genes if they too are keyed into hypoxia through a cytochrome C oxidase-mediated signal (Abramova et al. 2001a,b). The importance of Hap1p, a heme-activated transcription factor, in the activation of ERG genes again suggested that heme levels may have a prominent role in the regulation of Upc2p and Ecm22p.

If the activation of either Upc2p or Ecm22p were the result of reduced heme A, rather than the result of sterol depletion, depleting sterols without lowering heme A levels would not be expected to induce ERG gene expression through that transcription factor. To test this hypothesis directly, ketoconazole was used to deplete sterols. Ketoconazole inhibits Erg11p, an ergosterol biosynthetic enzyme that acts in the sterol-specific part of the pathway, downstream of the point from which nonsterol products of the pathway, such as heme A, are derived. By treating with ketoconazole, sterols can be depleted without depleting the nonsterol products of the pathway. If changes in Upc2p and Ecm22p activity or levels were indeed the result of heme depletion and not sterol depletion, following ketoconazole treatment neither ERG2 expression nor Upc2p or Ecm22p levels would be expected to change as they do following lovastatin treatment. In wild-type, upc2Δ (JRY7179), ecm22Δ (JRY7180), and upc2Δecm22Δ (JRY7181) strains treated with ketoconazole, induction of ERG2 was similar to that seen after lovastatin treatment (Figure 6A). More tellingly, Upc2p and Ecm22p levels following ketoconazole treatment changed just as with lovastatin treatment (Figure 6B). Thus, induction of ERG genes and changes in Upc2p and Ecm22p levels resulted from sterol depletion and not from depletion of heme A or any other early product from the sterol pathway.

Figure 6.—

(A) Ketoconazole induced ERG2 expression in wild-type and upc2Δ and ecm22Δ single deletion strains. Wild-type W303, upc2Δ (JRY7179), ecm22Δ (JRY7180), and upc2Δecm22Δ (JRY7181) strains were transformed with a pERG2∷lacZ reporter (pJR2316). Strains were grown in the presence or absence of 25 μg/ml ketoconazole. Extracts prepared from these cultures were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in materials and methods. (B) Upon sterol depletion, the level of Upc2p increased and the level of Ecm22p decreased. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from JRY7865 (UPC2-TAP) and JRY7866 (ECM22-TAP) grown in the presence of lovastatin (5 μg/ml or 30 μg/ml), ketoconazole (25 μg/ml), or no drugs. Protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in materials and methods. Arrows indicate tagged proteins.

Hypoxic sterol depletion activates Upc2p and Ecm22p targets:

A number of Upc2p targets, including the DAN/TIR genes, are induced under hypoxic conditions (Abramova et al. 2001a,b; Ter Linde et al. 2003). This observation led to the view that Upc2p is activated in response to low heme levels (Abramova et al. 2001b; Kwast et al. 2002), as heme biosynthesis is tightly controlled by oxygen, and heme levels often serve as a surrogate for oxygen levels (Zhang and Hach 1999; Hon et al. 2003). However, as ergosterol biosynthesis also requires oxygen (Parks 1978), hypoxic conditions would also lead to reduced sterol biosynthesis and might activate Upc2p by reducing sterol levels rather than heme levels.

To test whether hypoxic targets of Upc2p were induced in response to sterol depletion or heme depletion, the expression of several Upc2p/Ecm22p target genes was measured by quantitative RT–PCR in wild-type, upc2Δ, ecm22Δ, and upc2Δecm22Δ strains grown aerobically with or without ketoconazole or hypoxically with or without hemin (Table 2). The logic behind this experiment is as follows: genes that are induced by sterol depletion should be induced both by ketoconazole treatment and by hypoxic growth, and addition of hemin should not reduce hypoxic induction. Genes induced only by low heme should not be induced by ketoconazole, but should be induced under hypoxic growth. When hemin is added to hypoxically growing strains, hypoxic induction should be reduced or eliminated, as heme is no longer limiting. If a gene is activated by low heme and low sterols in combination, ketoconazole might induce the gene to some degree, while hypoxia will result in even greater induction. Adding hemin should reduce, but not eliminate, hypoxic induction of such genes, as sterols will still be limiting.

TABLE 2.

Induction of gene expression

| Gene | Condition | W303 | upc2Δ | ecm22Δ | upc2Δecm22Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANB1 | Ketoconazole | 1.23 (±0.01) | 0.90 (±0.03) | 1.64 (±0.54) | 0.64 (±0.21) |

| Hypoxia | 139 (±22.0) | 148 (±10.8) | 165 (±6.34) | 67.5 (±1.89) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 8.43 (±1.02) | 37.0 (±1.24) | 17.3 (±2.05) | 4.87 (±0.45) | |

| COX5b | Ketoconazole | 0.80 (±0.09) | 0.67 (±0.09) | 0.62 (±0.01) | 0.86 (±0.41) |

| Hypoxia | 2.63 (±0.50) | 2.63 (±0.14) | 3.6 (±0.10) | 2.80 (±0.12) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 0.99 (±0.21) | 1.34 (±0.01) | 0.98 (±0.20) | 0.74 (±0.14) | |

| ERG2 | Ketoconazole | 2.99 (±0.40) | 1.51 (±0.13) | 2.58 (±0.35) | 0.39 (±0.17) |

| Hypoxia | 2.98 (±0.17) | 5.11 (±0.48) | 3.34 (±0.01) | 2.67 (±0.28) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 2.60 (±0.61) | 4.32 (±0.70) | 2.13 (±0.27) | 0.79 (±0.09) | |

| ERG3 | Ketoconazole | 3.46 (±0.97) | 2.47 (±0.42) | 2.09 (±0.23) | 0.43 (±0.03) |

| Hypoxia | 5.3 (±0.27) | 7.27 (±0.78) | 3.21 (±0.18) | 12.4 (±0.48) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 6.0 (±1.52) | 8.33 (±0.28) | 2.79 (±0.13) | 3.38 (±0.06) | |

| ERG10 | Ketoconazole | 1.95 (±0.12) | 1.40 (±0.01) | 2.02 (±0.44) | 0.51 (±0.31) |

| Hypoxia | 2.72 (±0.44) | 3.65 (±0.51) | 3.94 (±0.56) | 4.69 (±2.59) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 2.09 (±0.95) | 3.44 (±0.29) | 3.13 (±0.83) | 0.81 (±0.23) | |

| IDI1 | Ketoconazole | 1.14 (±0.14) | 0.88 (±0.20) | 0.74 (±0.13) | 0.52 (±0.13) |

| Hypoxia | 7.46 (±0.33) | 7.11 (±0.93) | 5.76 (±0.02) | 4.81 (±1.12) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 2.63 (±0.18) | 4.95 (±1.33) | 2.91 (±0.04) | 1.98 (±0.18) | |

| TIR1 | Ketoconazole | 6.99 (±1.21) | 1.26 (±0.06) | 6.66 (±1.56) | 1.61 (±0.40) |

| Hypoxia | 70.7 (±6.44) | 1457 (±6.78) | 295 (±13.5) | 33.5 (±0.31) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 11.8 (±2.17) | 176 (±25.4) | 52.5 (±5.50) | 2.34 (0.04) | |

| DAN1 | Ketoconazole | 12.2 (±4.4) | 1.59 (±0.12) | 27.7 (±12.0) | 2.17 (±0.11) |

| Hypoxia | 1474 (±136) | 1800 (±643) | 3259 (±191) | 35.8 (±2.08) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 287 (±59.7) | 145 (±39.3) | 485 (±72.0) | 11.7 (±0.85) | |

| DAN2 | Ketoconazole | 2.06 (±0.03) | 1.22 (±0.15) | 2.93 (±0.28) | 1.39 (±0.84) |

| Hypoxia | 5.29 (±1.05) | 2.11 (±0.15) | 18.6 (±1.70) | 1.79 (±0.47) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 3.99 (±1.11) | 3.06 (±1.79) | 7.3 (±1.27) | 1.33 (±0.19) | |

| DAN4 | Ketoconazole | 2.32 (±0.22) | 1.25 (±0.26) | 1.83 (±0.18) | 0.76 (±0.27) |

| Hypoxia | 5.32 (±0.30) | 1.97 (±0.33) | 2.90 (±0.08) | 1.15 (±0.17) | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 2.38 (±0.17) | 1.63 (±0.62) | 2.52 (±0.35) | 0.90 (±0.11) | |

| UPC2 | Ketoconazole | 3.50 (±1.12) | NA | 6.31 (±2.44) | NA |

| Hypoxia | 2.03 (±0.23) | NA | 2.05 (±0.08) | NA | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 3.47 (±1.27) | NA | 3.11 (±0.54) | NA | |

| ECM22 | Ketoconazole | 1.64 (±0.18) | 0.92 (±0.12) | NA | NA |

| Hypoxia | 3.67 (±0.42) | 2.09 (±0.05) | NA | NA | |

| Hypoxia + hemin | 1.63 (±0.37) | 1.61 (±0.40) | NA | NA |

Induction is shown as fold-change over aerobic gene expression (without ketoconazole and without heme). NA, not applicable.

COX5b and ANB1 are known to be induced by hypoxia due to low heme. Neither contains the SRE promoter element to which Upc2p and Ecm22p bind. As expected, the expression of both COX5b and ANB1 was induced under hypoxic conditions, but not by ketoconazole. Hypoxic induction was greatly reduced by the addition of heme (Table 2).

ERG2, ERG3, ERG10, and IDI1 all encode enzymes in the sterol biosynthesis pathway. ERG2 and ERG3 encode late enzymes in the sterol-specific branch of the pathway and are known targets of Upc2p and Ecm22p (Vik and Rine 2001; Davies et al. 2005). ERG10 encodes the enzyme that catalyzes the first step in the pathway and contains a potential SRE in its promoter. IDI1 also encodes an early gene in the sterol pathway, but does not contain an SRE in its promoter. Expression of ERG2, ERG3, and ERG10 was induced by ketoconazole, but this induction required either Upc2p or Ecm22p. Hypoxia also induced these three genes, and when either Upc2p or Ecm22p is present hypoxic induction is not affected by the addition of heme. Interestingly, in the absence of both Upc2p and Ecm22p, hypoxic induction of ERG2, ERG3, and ERG10 is observed. This Upc2/Ecm22p-independent induction appeared to be a response to low heme, as the addition of heme greatly reduced the hypoxic response. In contrast, IDI1 was not induced by sterol depletion, but, as with the other three ERG genes, was induced by hypoxia in a Upc2p- and Ecm22p-independent manner. Thus it appeared that hypoxia created two induction signals, one mimicked by ketoconazole that could not be suppressed by hemin and a second that could be. The hemin suppression was robust only in the upc2Δecm22Δ strain, which lacked the proteins that respond to sterol depletion.

The DAN/TIR genes encode hypoxically expressed mannoproteins and are known targets of Upc2p induction (Abramova et al. 2001a,b). DAN1 and TIR1 appeared to be induced both by low sterols and by low heme. Ketoconazole treatment resulted in some induction, but hypoxic induction was 10- to 100-fold higher than ketoconazole induction. Much, but not all, of the hypoxic induction could be abated by adding back heme. This result is consistent with previous reports that DAN1 and TIR1 expression are regulated both by Upc2p and by Rox1p, a transcriptional repressor that is expressed when heme levels are high (Abramova et al. 2001b; Kwast et al. 2002; Lai et al. 2005). DAN2 and DAN4, which are not regulated by Rox1p (Abramova et al. 2001b), appeared to be induced primarily by low sterols. Ketoconazole and hypoxia (with or without hemin) induced both genes in a Upc2p/Ecm22p-dependent manner. Interestingly, unlike previous reports, under hypoxic conditions Ecm22p was quite capable of inducing all of the DAN/TIR genes tested.

UPC2 itself was induced by ketoconazole and by hypoxia, consistent with previous reports (Abramova et al. 2001b; Agarwal et al. 2003; Davies et al. 2005). The addition of heme to hypoxically growing cells did not reduce induction of UPC2, indicating that this induction was a result of low sterols rather than of low heme. Thus, as reported previously, Upc2p appears to be autoregulated, most likely through the SRE elements in its promoter (Abramova et al. 2001b).

ECM22 expression was modestly induced by hypoxia. This induction could be suppressed by additional heme, indicating that this induction was the result of heme depletion. As reported above, activation of target genes by Ecm22p was the result of low sterols, suggesting a certain disconnect between ECM22 expression and Ecm22p activity.

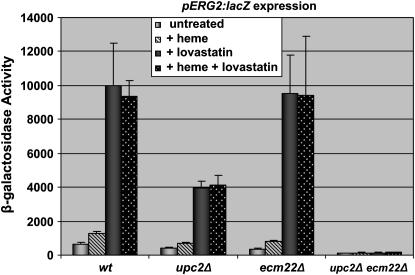

To control for the possibility that sterol depletion might create an unanticipated hypoxic response through heme levels, ERG2 expression was monitored in the presence and absence of lovastatin and in the presence and absence of exogenous heme. No effects of heme levels on induction by sterol depletion were evident under these conditions (Figure 7). Thus, although hypoxic conditions created depletion of both heme and sterol levels, the responses to heme and sterol depletion were distinct and resolvable.

Figure 7.—

Additional heme did not affect lovastatin induction of ERG2 expression. The indicated strains were transformed with a pERG2∷lacZ reporter (pJR2316). Strains were grown untreated or in the presence of 30 μg/ml lovastatin or 30 μg/ml lovastatin and 40 μg/ml hemin. Extracts prepared from these cultures were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in materials and methods.

DISCUSSION

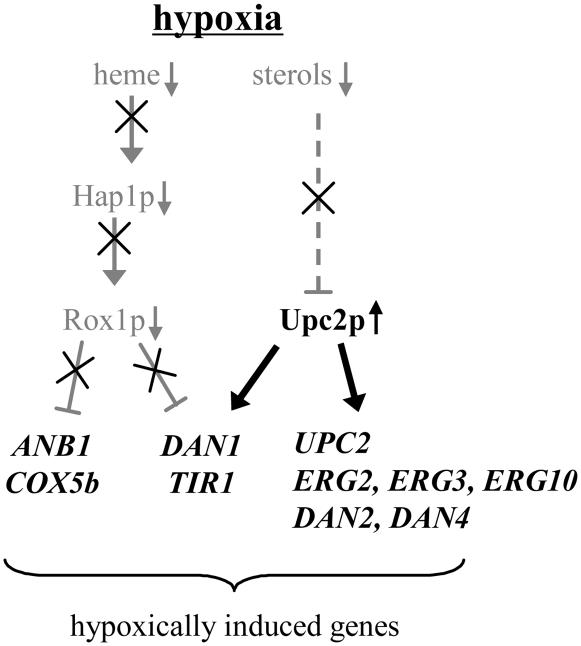

In addition to respiration, molecular oxygen is required for several important yeast cell processes, including the biosynthesis of heme and the biosynthesis of ergosterol (Parks 1978; Hon et al. 2003). Therefore, it is important for the cell to monitor oxygen levels and regulate these processes accordingly. In S. cerevisiae heme has been thought to be the primary oxygen sensor in the cell. Because heme biosynthesis is tightly regulated by oxygen, heme levels reflect oxygen availability (Zhang and Hach 1999; Hon et al. 2003). Sterol levels may also play a role in oxygen sensing. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the SREBP ortholog Sre1 activates both those genes required for adaptation to hypoxia and the ergosterol biosynthetic genes (Hughes et al. 2005). Although S. cerevisiae lacks orthologs to the SREBP and SCAP, the results presented here suggest an analogous, but not homologous, oxygen-sensing mechanism in budding yeast.

Upc2p and Ecm22p regulate the expression of many of the ergosterol biosynthesis (ERG) genes (Vik and Rine 2001; Germann et al. 2005) as well as the transcription of several hypoxically expressed genes, including genes involved in anaerobic cell wall reorganization and anaerobic sterol uptake (Abramova et al. 2001a,b; Wilcox et al. 2002). As expression of these genes responds to oxygen availability, it makes sense that the activity of Upc2p and Ecm22p must also be regulated by oxygen. Because low oxygen limits biosynthesis of both heme and sterols, regulation of Upc2p and Ecm22p activity may respond to either or to both of these signals.

One important result of this study was the clear identification of sterol levels as the primary regulator of Upc2p (see Figure 8). The activation of target genes by Upc2p occurred in response to low sterols, whether caused by early blocks in ergosterol biosynthesis (lovastatin), by late blocks (ketoconazole), or by hypoxia. ERG2, ERG3, ERG10, DAN2, and DAN4 were activated by Upc2p solely in response to sterol depletion rather than to heme depletion, whereas DAN1 and TIR1 responded to both sterols and heme (Table 2), consistent with previously reported repression of these genes by Rox1p and Mot3p and activation by Upc2p (Abramova et al. 2001b).

Figure 8.—

A simplified model of hypoxic induction of gene expression.

Like Upc2p, Ecm22p was able to induce SRE-containing ERG genes in response to sterol depletion (See Figure 6 and Table 2). Contrary to previous reports, Ecm22p also activated DAN/TIR genes in response to hypoxia. Previous studies used strains derived from S288C, with its mutant version of HAP1 (Abramova et al. 2001a,b), whereas this study used W303. However if that is the explanation for the discrepancy, then Hap1p must aid activation by Ecm22p despite decreasing heme levels under hypoxic conditions. No large-scale study comparing the hypoxic responses of S288c and W303 has been reported.

Clearly, both heme levels and sterol levels contribute to oxygen sensing in yeast. Although the role of heme in oxygen sensing has been well studied (Zhang and Hach 1999; Hon et al. 2003), the broader role of Upc2p and its activation in response to oxygen through sterol depletion is just beginning to emerge. Several targets have been identified (Abramova et al. 2001b; Vik and Rine 2001; Agarwal et al. 2003; Ter Linde et al. 2003; Germann et al. 2005), but if, as indicated by Kwast et al. (2002), Upc2p regulates nearly one-third of all anaerobically expressed genes, activation of Upc2p targets following sterol depletion represents a significant contribution to the adaptation to hypoxia.

Certainly, response to low heme and response to low sterols are not completely separable. Even within a specific pathway, such as ergosterol biosynthesis or the DAN/TIR gene family, mechanisms responding to both low heme and low sterols are at work. The involvement of Hap1p in ergosterol biosynthesis serves as one such example. Both Upc2p and Ecm22p required a functional version of Hap1p for basal expression of ERG2 (Figure 1). In contrast, when sterols were depleted with lovastatin, Upc2p's dependence on Hap1p was largely abolished, as robust induction of ERG2 was observed, whereas Ecm22p still depended upon Hap1p for ERG gene activation. Upc2p's ability to induce ERG2 expression in the absence of Hap1p may be the consequence of several factors. Both Upc2p levels and the amount of Upc2p at ERG promoters increase upon sterol depletion (Davies et al. 2005), whereas Ecm22p levels and their occupancy at SREs decreased. The derepression of Upc2p activity upon sterol depletion (Davies et al. 2005) and the resulting increases in Upc2p levels may enable Upc2p to induce ERG2 expression in a HAP1-independent manner.

It is unlikely that the need for both Hap1p and Upc2p or Hap1p and Ecm22p for basal gene expression is limited to ERG2. Full expression of HMG1 requires both the Hap1p binding site and an additional 55-bp region in its promoter (Tamura et al. 2004). This region contains the SRE binding site for Upc2p and Ecm22p (Vik and Rine 2001). Indeed, conserved core consensus binding sites are found for both Hap1p and Upc2p/Ecm22p in several ERG genes (Chiang et al. 2003).

The involvement of Mot3p in ERG gene expression revealed that ERG gene expression involved both induction and repression. Mot3p modulates the transcription of a diverse set of genes in a dosage-dependent manner (Grishin et al. 1998; Abramova et al. 2001a). Mot3p acts in combination with Rox1p to recruit the Tup1-Ssn6 repressor complex to anaerobically expressed genes under aerobic conditions (Kastaniotis and Zitomer 2000; Mennella et al. 2003; Sertil et al. 2003; Klinkenberg et al. 2005). Mot3p inhibited Ecm22p, but not Upc2p (Figure 3), and the direct physical interaction of Mot3p with Ecm22p (Figure 5) was likely an important part of the inhibitory mechanism. Mot3p inhibited Ecm22p-mediated ERG2 activation both before and after sterol depletion, so it remains unclear what signal or influence Mot3p responds to. Mot3p seemed to play some role in the decreased Ecm22p levels under inducing conditions, but not under noninducing conditions (Figure 4A).

One unexpected result from this study was the component of the hypoxic induction of ERG genes that was Upc2p/Ecm22p independent. In the absence of Upc2p and Ecm22p, all the ERG genes tested, including IDI1, were hypoxically induced (Table 2). Unlike Upc2p- or Ecm22p-dependent induction, this induction responded to heme levels rather than to sterol levels. None of the DAN/TIR genes exhibited this type of induction, suggesting that this type of gene activation was specific to the ergosterol pathway. It is unlikely that this activation results from depression by Rox1p or Mot3p, as deletion of ROX1 does not change expression of any ERG genes apart from ERG26 and HMG2 (Ter Linde and Steensma 2002), and, in the absence of Upc2p or Ecm22p, deletion of MOT3 does not result in induction of ERG2 (Figure 3).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (GM35827). B.S.J.D. was supported in part by training grants from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Abramova, N., O. Sertil, S. Mehta and C. V. Lowry, 2001. a Reciprocal regulation of anaerobic and aerobic cell wall mannoprotein gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 183: 2881–2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramova, N. E., B. D. Cohen, O. Sertil, R. Kapoor, K. J. Davies et al., 2001. b Regulatory mechanisms controlling expression of the DAN/TIR mannoprotein genes during anaerobic remodeling of the cell wall in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 157: 1169–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, A. K., P. D. Rogers, S. R. Baerson, M. R. Jacob, K. S. Barker et al., 2003. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to polyene, pyrimidine, azole, and echinocandin antifungal agents in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 34998–35015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alimardani, P., M. Regnacq, C. Moreau-Vauzelle, T. Ferreira, T. Rossignol et al., 2004. SUT1-promoted sterol uptake involves the ABC transporter Aus1 and the mannoprotein Dan1 whose synergistic action is sufficient for this process. Biochem. J. 381: 195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, A., and T. J. B. Stier, 1953. Anaerobic mutrition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Ergosterol requirement for growth in defined medium. J. Cell Comp. Physiol. 41: 23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthington-Skaggs, B. A., D. N. Crowell, H. Yang, S. L. Sturley and M. Bard, 1996. Positive and negative regulation of a sterol biosynthetic gene (ERG3) in the post-squalene portion of the yeast ergosterol pathway. FEBS Lett. 392: 161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, C. B., A. Davies, G. J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li et al., 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14: 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, D., D. Dawson and T. Stearns, 2000. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Woodbury, NY

- Chiang, D. Y., A. M. Moses, M. Kellis, E. S. Lander and M. B. Eisen, 2003. Phylogenetically and spatially conserved word pairs associated with gene-expression changes in yeasts. Genome Biol. 4: R43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, J. H., F. W. Leak, Jr., K. V. Shianna, S. Tove and L. W. Parks, 1998. A mutation in a purported regulatory gene affects control of sterol uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 180: 4177–4183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B. S., H. S. Wang and J. Rine, 2005. Dual activators of the sterol biosynthetic pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: similar activation/regulatory domains but different response mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 7375–7385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimster-Denk, D., and J. Rine, 1996. Transcriptional regulation of a sterol-biosynthetic enzyme by sterol levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 3981–3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimster-Denk, D., M. K. Thorsness and J. Rine, 1994. Feedback regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 5: 655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foiani, M., F. Marini, D. Gamba, G. Lucchini and P. Plevani, 1994. The B subunit of the DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae executes an essential function at the initial stage of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 923–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaisne, M., A. M. Becam, J. Verdiere and C. J. Herbert, 1999. A ‘natural’ mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains derived from S288c affects the complex regulatory gene HAP1 (CYP1). Curr. Genet. 36: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbart, M. E., T. Rechsteiner, T. J. Richmond and T. Tsukiyama, 2001. Interactions of Isw2 chromatin remodeling complex with nucleosomal arrays: analyses using recombinant yeast histones and immobilized templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 2098–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann, M., C. Gallo, T. Donahue, R. Shirzadi, J. Stukey et al., 2005. Characterizing sterol defect suppressors uncovers a novel transcriptional signaling pathway regulating zymosterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 35904–35913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker, 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15: 1541–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J. L., R. B. Rawson and M. S. Brown, 2002. Mutant mammalian cells as tools to delineate the sterol regulatory element-binding protein pathway for feedback regulation of lipid synthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 397: 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishin, A. V., M. Rothenberg, M. A. Downs and K. J. Blumer, 1998. Mot3, a Zn finger transcription factor that modulates gene expression and attenuates mating pheromone signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 149: 879–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon, T., A. Dodd, R. Dirmeier, N. Gorman, P. R. Sinclair et al., 2003. A mechanism of oxygen sensing in yeast. Multiple oxygen-responsive steps in the heme biosynthetic pathway affect Hap1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 50771–50780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongay, C., N. Jia, M. Bard and F. Winston, 2002. Mot3 is a transcriptional repressor of ergosterol biosynthetic genes and is required for normal vacuolar function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 21: 4114–4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A. L., B. L. Todd and P. J. Espenshade, 2005. SREBP pathway responds to sterols and functions as an oxygen sensor in fission yeast. Cell 120: 831–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastaniotis, A. J., and R. S. Zitomer, 2000. Rox1 mediated repression. Oxygen dependent repression in yeast. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 475: 185–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M. A., R. Barbuch and M. Bard, 1999. Transcriptional regulation of the squalene synthase gene (ERG9) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1445: 110–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkenberg, L. G., T. A. Mennella, K. Luetkenhaus and R. S. Zitomer, 2005. Combinatorial repression of the hypoxic genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by DNA binding proteins Rox1 and Mot3. Eukaryot. Cell 4: 649–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobor, M. S., S. Venkatasubrahmanyam, M. D. Meneghini, J. W. Gin, J. L. Jennings et al., 2004. A protein complex containing the conserved Swi2/Snf2-related ATPase Swr1p deposits histone variant H2A.Z into euchromatin. PLoS Biol. 2: E131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwast, K. E., P. V. Burke, B. T. Staahl and R. O. Poyton, 1999. Oxygen sensing in yeast: evidence for the involvement of the respiratory chain in regulating the transcription of a subset of hypoxic genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 5446–5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwast, K. E., L. C. Lai, N. Menda, D. T. James, III, S. Aref et al., 2002. Genomic analyses of anaerobically induced genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: functional roles of Rox1 and other factors in mediating the anoxic response. J. Bacteriol. 184: 250–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L. C., A. L. Kosorukoff, P. V. Burke and K. E. Kwast, 2005. Dynamical remodeling of the transcriptome during short-term anaerobiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: differential response and role of Msn2 and/or Msn4 and other factors in galactose and glucose media. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 4075–4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, T. L., G. A. Keesler, G. P. Fenner and L. W. Parks, 1988. Pleiotropic mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae affecting sterol uptake and metabolism. Yeast 4: 93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennella, T. A., L. G. Klinkenberg and R. S. Zitomer, 2003. Recruitment of Tup1-Ssn6 by yeast hypoxic genes and chromatin-independent exclusion of TATA binding protein. Eukaryot. Cell 2: 1288–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, C. T., F. Diaz and A. Barrientos, 2004. Defects in the biosynthesis of mitochondrial heme c and heme a in yeast and mammals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1659: 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, L. W., 1978. Metabolism of sterols in yeast. CRC Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 6: 301–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut, G., A. Shevchenko, B. Rutz, M. Wilm, M. Mann et al., 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17: 1030–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M. E., T. A. Brown and B. L. Trumpower, 1990. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 3091–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sertil, O., R. Kapoor, B. D. Cohen, N. Abramova and C. V. Lowry, 2003. Synergistic repression of anaerobic genes by Mot3 and Rox1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 5831–5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shianna, K. V., W. D. Dotson, S. Tove and L. W. Parks, 2001. Identification of a UPC2 homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its involvement in aerobic sterol uptake. J. Bacteriol. 183: 830–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. J., J. H. Crowley and L. W. Parks, 1996. Transcriptional regulation by ergosterol in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 5427–5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., Y. Gu, Q. Wang, T. Yamada, K. Ito et al., 2004. A hap1 mutation in a laboratory strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in decreased expression of ergosterol-related genes and cellular ergosterol content compared to sake yeast. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 98: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Linde, J. J., and H. Y. Steensma, 2002. A microarray-assisted screen for potential Hap1 and Rox1 target genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 19: 825–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Linde, J. J., M. Regnacq and H. Y. Steensma, 2003. Transcriptional regulation of YML083c under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Yeast 20: 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsness, M., W. Schafer, L. D'Ari and J. Rine, 1989. Positive and negative transcriptional control by heme of genes encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9: 5702–5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik, A., and J. Rine, 2001. Upc2p and Ecm22p, dual regulators of sterol biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 6395–6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A. D., D. G. Edmondson, J. R. Bone, Y. Mukai, Y. Yu et al., 2000. Ssn6-Tup1 interacts with class I histone deacetylases required for repression. Genes Dev. 14: 2737–2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, L. J., D. A. Balderes, B. Wharton, A. H. Tinkelenberg, G. Rao et al., 2002. Transcriptional profiling identifies two members of the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily required for sterol uptake in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 32466–32472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., and A. Hach, 1999. Molecular mechanism of heme signaling in yeast: the transcriptional activator Hap1 serves as the key mediator. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56: 415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]