Abstract

Perturbation of the protein-folding environment in the mitochondrial matrix selectively upregulates the expression of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. To identify components of the signal transduction pathway(s) mediating this mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), we first isolated a temperature-sensitive mutation (zc32) that conditionally activates the UPRmt in C. elegans and subsequently searched for suppressors by systematic inactivation of genes. RNAi of ubl-5, a gene encoding a ubiquitin-like protein, suppresses activation of the UPRmt markers hsp-60∷gfp and hsp-6∷gfp by the zc32 mutation and by other manipulations that promote mitochondrial protein misfolding. ubl-5 (RNAi) inhibits the induction of endogenous mitochondrial chaperone encoding genes hsp-60 and hsp-6 and compromises the ability of animals to cope with mitochondrial stress. Mitochondrial morphology and assembly of multi-subunit mitochondrial complexes of biotinylated proteins are also perturbed in ubl-5(RNAi) worms, indicating that UBL-5 also counteracts physiological levels of mitochondrial stress. Induction of mitochondrial stress promotes accumulation of GFP-tagged UBL-5 in nuclei of transgenic worms, suggesting that UBL-5 effects a nuclear step required for mounting a response to the threat of mitochondrial protein misfolding.

PROTEIN chaperones are essential to the biogenesis of newly synthesized proteins and to the degradation of misfolded and mis-assembled proteins (Bukau and Horwich 1998; Horwich et al. 1999; Hartl and Hayer-Hartl 2002). Homeostasis requires a balance between the load of newly synthesized unfolded proteins or existing misfolded proteins and the levels of chaperones in the various cellular compartments. This balance is maintained by signal transduction pathways that respond to fluctuations in unfolded and misfolded protein load and appropriately activate genes encoding chaperones targeted to the stressed compartment. Such pathways are referred to as unfolded protein responses (UPR).

First identified in bacteria exposed to elevated temperatures, signaling pathways responsive to unfolded/misfolded proteins were subsequently recognized in the cytosol of all cells where they came to be known as the heat-shock response (Lindquist and Craig 1988). The effectors of activated gene expression in the heat-shock response are well characterized. In bacteria a specific σ-factor, σ32, is stabilized by the accumulation of misfolded cytoplasmic proteins, an event that correlates with reduced binding of σ32 to chaperones. As a consequence, RNA polymerase is directed to the promoters of genes encoding chaperones whose enhanced expression restores balance to the protein-folding environment in the cytosol (Bukau 1993; Biaszczak et al. 1999). In eukaryotes, specific transcription factors, heat-shock factors, are activated by the accumulation of unfolded/misfolded proteins in the cytosol (Wu 1995; Cotto and Morimoto 1999) and these bind to and activate hundreds of genes involved in adapting to the stress of protein misfolding in the eukaryotic cytosol (Murray et al. 2004).

A conceptually similar signal transduction pathway couples the stress of protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to activation of a gene expression program upregulating ER chaperones and other components of the secretory machinery. Signaling in this ER unfolded protein response (UPRer) is initiated by ER transmembrane proteins whose lumenal domains sense the compartment-specific stress signal and whose cytoplasmic domains propagate the signal to the nucleus to activate genes that elicit a compartment-specific adaptation (Patil and Walter 2001; Harding et al. 2002; Kaufman et al. 2002).

The mitochondrial matrix presents a third discrete compartment for protein folding in eukaryotic cells. Most mitochondrial proteins are synthesized in the cytosol and are imported into the organelle across the outer and inner membrane in an unfolded state (Neupert 1997). A much smaller number of very abundant proteins are synthesized in the mitochondrial matrix. Compartment-specific chaperones assist in the translocation of cytosolic proteins into the organelle and subsequently in the folding of both imported and locally synthesized proteins (Voos and Rottgers 2002). Many mitochondrial proteins are proteolytically processed and further assembled into multi-subunit functional complexes of defined stoichiometry.

There are two major classes of matrix chaperones: Hsp70 homologs and Hsp60/Hsp10 homologs (of bacterial GroE) (Neupert 1997; Voos and Rottgers 2002). Together with an assortment of proteases (e.g., SPG7, ClpP) (Langer et al. 2001) and more specific assembly factors (e.g., Opa1, Prohibitin) (Nijtmans et al. 2000), these chaperones constitute a protein-handling machinery that plays an essential role in mitochondrial biogenesis and maintenance. Loss-of-function mutations in mitochondrial chaperones and other components of the aforementioned machinery are associated with a variety of mainly neurological diseases (Lindholm et al. 2004). The phenotypic convergence of these mutations and the slowly progressive nature of some of the associated diseases suggest that alterations of the protein-folding environment in the mitochondria might also contribute to sporadic diseases of aging (Beal 2005). This has generated an interest in the mechanisms by which cells cope with protein misfolding in the mitochondria.

Mitochondrial chaperones are encoded by nuclear genes that are selectively activated by genetic and pharmacological manipulations that impair the protein-folding environment in the mitochondrial matrix. Interfering with the expression of the mitochondrial genome, which is predicted to lead to accumulation of unassembled imported precursors of multi-subunit mitochondrial complexes, activates mitochondrial chaperone-encoding genes in rho− mammalian cells (Martinus et al. 1996). Overexpression of a folding-impaired matrix enzyme, mutant ornithine transcarbamylase, activates genes encoding the mitochondrial chaperones Hsp60/Hsp10 and the protease ClpP in mammalian cells (Zhao et al. 2002). In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans inactivation of mitochondrial chaperones, proteases, or assembly factors selectively upregulates hsp-60 and hsp-6, encoding, respectively, mitochondrial Hsp60 and Hsp70 proteins (Yoneda et al. 2004). Together these observations point to the existence of a signal transduction pathway that responds to the stress of unfolded/misfolded proteins in the mitochondrial matrix and selectively activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. Here we describe a screen for genes encoding putative components of such a mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) and report on the identification of one such gene whose product appears to function at a nuclear step in the response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic and mutant C. elegans strains:

Strains containing the mitochondrial misfolded protein stress reporters hsp-6∷gfp(zcIs13) V (SJ4100) and hsp-60∷gfp(zcIs9) V (SJ4058) and the ER stress reporters hsp-4∷gfp(zcIs4) V (SJ4005) and hsp-4∷gfp(zcIs4) V; upr-1(zc6) X (SJ6) have been previously described (Calfon et al. 2002; Yoneda et al. 2004). The myo-3∷gfpmt plasmid expressing a mitochondrially localized green fluorescent protein (GFP) (GFPmt) with a cleavable mitochondrial import signal peptide (Labrousse et al. 1999; a gift of A. van der Bliek, University of California at Los Angeles) was integrated stably, generating myo-3∷gfpmt(zcIs14) (SJ4103), and a control line expressing similar levels of cytoplasmic GFP, myo-3∷gfp(zcIs21), was created using the same myo-3 promoter (SJ4157). The gfpmt-expressing fragment was excised from myo-3∷gfpmt and inserted downstream of the ges-1 promoter to create a stable transgenic line expressing GFPmt in the adult intestinal cell, ges-1∷gfpmt(zcIs17) (SJ4143). The control line ges-1∷gfp(zcIs18) (SJ4144), expressing similar levels of cytoplasmic GFP, has been previously described (Urano et al. 2002). Strains expressing UBL-5 fused to GFP at the last residue were prepared by amplifying the ∼1750-bp genomic region containing the promoter and coding sequence of C. elegans ubl-5 using the primers F46F11.SalI.3S 5′-ATAAGTCGACTCTCCAGAAGAAACTTCACG-3′ and F46F11.BamHI.4AS 5′-TGATGGATCCTTGGTAGTAGAGCTCGAAATTGAATC-3′ and ligating the fragment into the SalI–BamHI sites of pPD95.77 to create UBL-5.pPD95.77.V1 and injecting N2 animals with the plasmid to create ubl-5∷gfp(zcIs19) X (SJ4151). In a second strain, ubl-5Cb∷gfp(zcIs22) I (SJ4153), the C. elegans ubl-5 coding sequence was replaced by the synonymous coding sequence of C. briggsae; a 463-bp BsaBI–SacI fragment of C. briggsae genomic DNA encoding UBL-5 was recovered by PCR using the primers UBL-5.brig.1S (5′-CAAGAAAAATGATCGAAATCACAGTGAATGATCGTC-3′) and UBL-5.brig.2AS (5′-GCTCATTGATAATAGAGCTCGAAGTTGAATCCC-3′) and used to replace the homologous C. elegans fragment to create UBL-5.brig1.pPD.95.77, which was injected into N2 animals. The ability of the transgene to rescue the ubl-5(RNAi) phenotype was assessed by two methods: (1) rescue of the growth defect in a hypersensitive eri-1(mg366) IV background obtained by crossing the SJ4153 and GR1373 strains and segregating ubl-5Cb∷gfp(zcIs22) transgenic and nontransgenic eri-1(mg366) IV F2 animals from the cross and (2) rescue of the defect in hsp-60∷gfp expression in a compound ubl-5Cb∷gfp(zcIs22) I; hsp-60∷gfp(zcIs9) V; zc32 II strain obtained by crossing SJ4153 and SJ52 strains and segregating progeny homozygous at all three loci.

The zc32 II mutant strain was isolated following EMS mutagenesis of hsp-60∷gfp(zcIs9). The F1 progeny of mutagenized animals were placed four per plate and their progeny (the F2 generation) were screened by inverted fluorescent microscopy for induction of the GFP reporter at 25°. The mutation was backcrossed into the N2 background to eliminate the reporter and other adventitial mutations creating the strain (SJ60) and was subsequently reconstituted with the hsp-60∷gfp(zcIs9) V (SJ52) or the hsp-6∷gfp(zcIs13) V (SJ71) transgene to be used in the RNA interference (RNAi) screen described below.

RNAi procedures:

RNAi of genes on chromosome I was carried out by sequential feeding of an arrayed library of genomic fragments obtained from the United Kingdom Human Genome Mapping Project Resource Center (Cambridge, UK) as described (Fraser et al. 2000). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 1 mm) was added to the bacterial growth media to induce transcription of the double-stranded RNA. Mock RNAi feeding was conducted with Escherichia coli transformed with the same plasmid, but lacking an insert; they, too, were cultured in the presence of 1 mm IPTG.

cDNA-based RNAi-feeding plasmids directed toward C. elegans and C. briggsae ubl-5 were constructed by reverse transcriptase PCR amplification of the coding sequence from whole-animal RNA. The C. elegans primers used were F46F11.Kpn.1S (5′-GGCCGGTACCATGATTGAAATCACAGTAAACGATC-3′) and F46F11.2AS (5′-GAAATGAATTCTGATGAATCATTGG-3′) and the C. briggsae cDNA was amplified using the same UBL-5.brig.1S and UBL-5.brig.2AS primers described above. The inserts were ligated into the pPD129.36 plasmid.

The screen for genes whose inactivation by RNAi interferes with hsp-60∷gfp expression was conducted by placing four SJ52 L4 larvae of the zc32 II; hsp-60∷gfp(zcIs9) V genotype on 60-mm plates seeded with E. coli strains carrying an RNAi-feeding plasmid and allowing their offspring to develop at the permissive temperature for 72 hr and then switching the plates to the nonpermissive temperature of 25° and observing, 24 hr later, the effects of the RNAi on growth, viability, fertility, and the expression of the hsp-60∷gfp. At this point, the plate was populated with both F1 and developing F2 progeny of the original four animals, allowing us to score the phenotype across three generations of RNAi exposure.

The timing of exposure to RNAi was varied to manipulate the level of gene inactivation, which enabled us to overcome lethal or growth-suppressive phenotypes associated with complete inactivation. Placing embryonated eggs purified from gravid animals on RNAi plates restricts exposure to the RNAi to the later stages of embryonic development and often bypasses the lethality associated with earlier inactivation of some genes. The phenotype was scored in the F0 animal. This design was used to study the interactions of zc32 with RNAi of mitochondrial chaperones (Figure 2) to measure the effect of ubl-5(RNAi) on induction of the mitochondrial chaperones (Figure 3, C and D), on mitochondrial morphology in myo-3∷gfpmt animals (Figure 4A), and on the assembly of protein complexes in the mitochondrial matrix (Figure 5B) and to study the effect of RNAi of mitochondrial chaperones on UBL-5∷GFP localization (Figure 6). In other experiments we measured the phenotype by assessing the effect of gene inactivation on the F1 progeny that develop on RNAi-feeding plates (Figure 3, A and B; Figure 4, B and C).

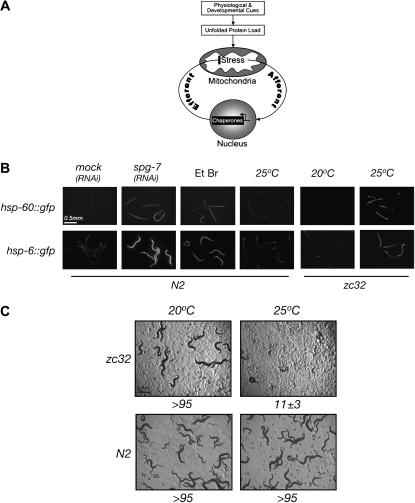

Figure 2.—

The zc32 mutation compromises the ability to cope with further mitochondrial stress. Shown are photomicrographs of plates with wild-type (N2) and zc32 mutant animals that developed at the permissive (20°) and nonpermissive temperature (25°) from embryos exposed to mock RNAi or RNAi of genes that induce further mitochondrial stress (spg-7, phb-2, and hsp-60) or ER stress (ire-1). Photographs were taken 84 hr after seeding the RNAi plates with embryonated eggs. The fraction of animals that reached developmental stage ≥L4 (mean ±SEM) is indicated below the images.

Figure 3.—

Inactivation of ubl-5 compromises signaling in the UPRmt. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs of wild-type (N2) and zc32 mutant animals transgenic for the UPRmt reporters hsp-6∷gfp and hsp-60∷gfp or for the UPRer reporter hsp-4∷gfp. Animals developed from founders placed on mock RNAi or ubl-5(RNAi) plates at 20° and were shifted, where indicated, to the nonpermissive temperature (25°) for 24 hr before analysis. The animals in the left panels were exposed to genomic-based RNAi whereas those on the right were exposed to cDNA-based RNAi constructs derived from C. elegans mRNA (Ce) or C. briggsae mRNA (Cb). Where indicated, the hsp-4∷gfp reporter was activated by exposure to the ER-stress-inducing drug tunicamycin [note that ubl-5(RNAi) does not affect the induction of hsp-4∷gfp]. (B) Photomicrographs of progeny of wild-type (N2) or zc32 founder animals that developed on mock or ubl-5(RNAi) plates maintained for 16 hr at the permissive temperature of 20° (to allow egg laying by the founder) and shifted to the nonpermissive temperature of 25° for 3 days. The number of F1 progeny that reached developmental stage ≥L4 (mean ±SEM)/F0 hermaphrodite is indicated below the images. (C) Immunoblot of GFP reporter in hsp-60∷gfp transgenic wild-type, zc32 mutant, or animals exposed to the indicated mitochondrial stress-inducing RNAi in the presence or absence of ubl-5(RNAi). The anti-HDEL blot, which detects C. elegans BiP, serves as a loading control. (D) Northern blot of endogenous hsp-60 and hsp-6 RNA in animals that developed on mock RNAi, spg-7(RNAi) (to induce mitochondrial stress), and a combination of spg-7(RNAi) and ubl-5(RNAi). Samples were processed 72 and 96 hr after seeding the RNAi plates with eggs. Ribosomal RNAs stained with ethidium bromide serve as a loading control. (E) Immunoblot of GFP, as in C. The GFP protein encoded by the hsp-60∷gfp(zcIs9) transgenic UPRmt reporter (hsp-60∷GFP) and the UBL-5Cb∷GFP fusion protein encoded by the rescuing transgenic allele of ubl-5Cb∷gfp(zcIs22) are indicated. The asterisk marks an immunoreactive protein fragment found in ubl-5Cb∷gfp(zcIs22) animals, which is likely an in vitro proteolytic fragment of the fusion protein. The anti-HDEL blot, which detects C. elegans BiP, serves as a loading control.

Figure 4.—

Inactivation of ubl-5 selectively compromises an animal's ability to cope with mitochondrial stress. (A) High-magnification fluorescent photomicrographs of mitochondria labeled with a GFP with a cleavable mitochondrial import signal (GFPmt) expressed from a myo-3∷gfpmt transgene. Animals developed to adulthood from embryos exposed to the indicated RNAi. Note the irregular morphology of the mitochondria in animals exposed to RNAi that induces mitochondrial stress (spg-7, hsp-60, phb-2) or inactivates ubl-5 and the normal morphology of the mock and ire-1(RNAi) animals. (B) Photomicrographs of plates populated by progeny (F1) of myo-3∷gfpmt or myo-3∷gfpcyt animals subjected to the indicated RNAi. The F0 animals had been removed from the plate. The number of F1 progeny that reached a developmental stage ≥L4 (mean ±SEM)/F0 hermaphrodite (n = 4) is indicated below the images. The panels at the far right are fluorescent photomicrographs of transgenic animals. (C) Photomicrographs of progeny produced by the F1 generation of mock and ubl-5(RNAi) transgenic animals expressing GFP in mitochondria (ges-1∷gfpmt) or cytoplasm (ges-1∷gfpcyt) of the intestinal cells. (D) Immunoblot of GFP and the anti-HDEL loading control in test and control pairs of myo-3∷gfpmt and myo-3∷gfpcyt or ges-1∷gfpmt and ges-1∷gfpcyt transgenic animals.

Figure 5.—

Inactivation of ubl-5 perturbs formation of protein complexes in the mitochondria. (A) Detection of an ∼75-kDa biotinylated protein(s) in fractionated worm extracts by strepavidin–HRP ligand blotting. Total worm extract (T), postmitochondrial supernatant (SN), and mitochondrial pellet (MT) are shown. GFPcyt expressed from the myo-3 promoter serves as a marker for a cytoplasmic protein. (B) Distribution of an ∼75-kDa biotinylated mitochondrial protein(s) in fractions of glycerol gradient prepared from animals exposed to mock RNAi, hsp-60(RNAi), and ubl-5(RNAi). (Top) Unstressed animals. (Bottom) Mitochondrially stressed myo-3∷gfpmt animals. The migration of complexes of the indicated size in this gradient is shown. The final fraction (14) also contains the pellet.

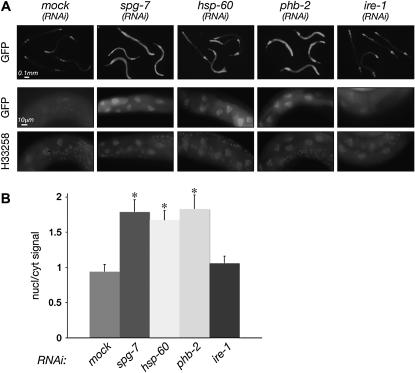

Figure 6.—

The stress of protein misfolding in the mitochondrial matrix promotes nuclear localization of UBL-5∷GFP. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs of ubl-5∷gfp transgenic animals that developed from larvae while exposed to the indicated RNAi. Shown are low magnification (top) and high-magnification (bottom) fluorescent micrographs of the GFP channel and the H33258 nuclear stain. Note that the large polyploid intestinal nuclei stain brightly with H33258 in all samples and with UBL-5∷GFP in the stressed samples. (B) The relative intensity of the cytosolic and nuclear UBL–GFP signal in animals subjected to the indicated genetic manipulations. The mean ±SEM ratio of signal from the nuclear and cytosolic regions of the intestinal cell is plotted (N = 20, * P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test, compared with mock sample).

The potential confounding effects of dilution on the outcome of double RNAi experiments were controlled by similar dilution of single RNAi-expressing bacteria with bacteria transformed with the empty RNAi expression plasmid pPD129.36.

Pharmacological treatment:

Ethidium bromide (Sigma, St. Louis) was dissolved in water at 10 mg/ml and added to agar plates to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml and tunicamycin was used at 1 μg/ml as previously described (Calfon et al. 2002; Yoneda et al. 2004).

Microscopy and image analysis:

Low-resolution images of live animals were obtained with an inverted dissecting microscope equipped with epifluorescent illumination (Zeiss Stemi SV 11 Apo) as described (Yoneda et al. 2004). Higher-resolution images were obtained by mounting animals on slides using a digital CCD camera attached to a Zeiss Axiophot 100 microscope. Where indicated, the samples were fixed (3.7% paraformaldehyde, 10 min at room temperature followed by 100% methanol, 5 min at −20°) and exposed to a 1:1000 dilution of H33258 dye to stain the nuclei. Images were constituted from composites of digital photographs obtained under identical exposure conditions.

Image analysis (Figure 6) was conducted by calculating the mean pixel intensity over the intestinal nuclei and an equal surface of cytoplasm using Volocity software for Mac OS X (Improvision, Coventry, UK). The measurements are reported as the mean nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio ±SEM of 20 nuclei from five animals of each genotype. Statistical analysis was performed by the unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test.

Northern blots, immunoblots, and detection of biotinylated protein by ligand blot:

Total RNA was prepared using the guanidine thiocyanate-acid–phenol-extraction method and 15 μg were applied to each lane of a 1.5% agarose gel. The hybridization probes used to detect hsp-6 and hsp-60 were previously described (Yoneda et al. 2004). Detection of GFP and BiP (by antibodies reactive with the tetra-peptide: His-Asp-Glu-Leu-COOH, anti-HDEL) by immunoblotting was as previously described (Marciniak et al. 2004; Yoneda et al. 2004).

Biotinylated mitochondrial proteins were detected following reducing SDS–PAGE and blotting to a nitrocellulose membrane that was reacted with horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, catalog no. 016-030-084) and the signal revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence, as previously described (Baumgartner et al. 2001). Subcellular fractionation of worm lysates and purification of mitochondria was achieved by equilibrium density centrifugation as described (Jonassen et al. 2002). Size fractionation of mitochondrial complexes by velocity gradient centrifugation was achieved by layering the Triton X-100 soluble proteins on a 10–40% v/v glycerol gradient in buffer A (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 50 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1.5 mm MgCl2), centrifuging the sample for 18 hr at 28,500 × g in a Beckman SW50 rotor, and blotting the individual fractions for their content of biotinylated proteins as described above.

RESULTS

Compartment-specific UPRs are predicted to share certain underlying principles. Developmental programs and physiological stimuli drive organelle biogenesis and specify its level of activity and thereby influence the load of unfolded proteins that confront chaperones in a particular compartment. The balance between unfolded/misfolded “client” protein load and available chaperones determines the level of stress in the compartment and the level of signaling in the afferent limb of the compartment-specific UPR (Figure 1A). Signaling in the afferent limb activates target genes encoding chaperones and other components of its efferent limb, restoring homeostasis to the organelle. Reporters linked to target gene promoters can be used to monitor signaling in the afferent limb of a UPR. Activation of the UPR is achieved by compromising the protein-folding environment in the compartment through pharmacological manipulations or by genetic inactivation of UPR effectors. In considering a screen for genes that constitute the afferent limb of a UPR, it is important to keep in mind that signaling may be suppressed by mutations that block signal transduction (interesting mutations) but also by mutations that reduce unfolded/misfolded (“client”) protein load (trivial, upstream suppressors).

Figure 1.—

(A) Hypothesized components of a mitochondrial UPR. Physiological and developmental cues impose an unfolded protein load on the mitochondria. The resultant physiological stress activates the afferent limb of the UPRmt, increasing expression of genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. The latter serve as the pathway's efferent limb that restores homeostasis to the organelle. A mutation such zc32 (see below), which activates the afferent limb by causing more mitochondrial stress, may achieve this by compromising the UPRmt's efferent limb or by imposing an increased burden of unfolded/misfolded proteins. A gene whose inactivation diminishes the activity of the afferent limb (ubl-5, see below) may function in propagating the stress signal or may suppress the pathway upstream by diminishing the load of unfolded/misfolded proteins that enter the organelle. (B) Activation of the UPRmt by a temperature-sensitive mutation, zc32. Shown are fluorescent micrographs of animals transgenic for a GFP reporter linked to the UPRmt-inducible promoters of the mitochondrial chaperone-encoding genes hsp-6 and hsp-60. Developing wild-type (N2) embryos were exposed to spg-7(RNAi) or to ethidium bromide (Et Br), which induce the UPRmt. Mutant zc32 embryos were allowed to develop to adulthood at the permissive or nonpermissive temperature. (C) Photomicrographs of progeny of wild-type (N2) and zc32 mutant adults that had developed at the permissive (20°) or nonpermissive (25°) temperature. The mean (±SEM) number of progeny per mutant hermaphrodite reaching the L4 stage is indicated below the photomicrograph.

We had previously established transgenic lines of C. elegans containing green fluorescent protein reporters driven by the UPRmt-inducible hsp-6 and hsp-60 promoters (Yoneda et al. 2004). Inactivation of genes that signal in the UPRmt is predicted to diminish the activity of these hsp-6∷gfp and hsp-60∷gfp reporters and serves as a criterion for the identification of components of this signal transduction pathway. However, to recognize animals impaired in signaling the UPRmt, the pathway needs to be robustly activated in the first place. The UPRmt can be activated by RNAi of numerous genes whose products encode mitochondrial chaperones, proteases, and even components of the mitochondrial gene expression program (Yoneda et al. 2004; Hamilton et al. 2005), but the toxicity of such manipulations and the incomplete penetrance of RNAi limit the utility of this approach in wide-scale genetic screens. Therefore, as a first step toward a screen for genes that function in the UPRmt we sought to identify a mutation that activates the pathway.

Isolating a mutation that conditionally activates the UPRmt:

The hsp-60∷gfp reporter has a faint basal activity but is robustly and specifically induced by manipulations that activate the UPRmt (Yoneda et al. 2004) (Figure 1B). We screened F2 progeny of EMS-mutagenized hsp-60∷gfp(zcIs9) transgenic worms for individuals with constitutive activity of the reporter. Such individuals were readily identified (250 of 7500 haploid genomes screened), an observation consistent with the large number of (likely nuclear) genes required for mitochondrial homeostasis (Table I in Yoneda et al. 2004). However, none of the constitutive UPRmt-active animals could be propagated as a mutant line. The latter observation is consistent with the requirement for mitochondrial integrity in development of the C. elegans germline (Tsang et al. 2001; Artal-Sanz et al. 2003).

A screen for temperature-sensitive (ts) mutations that conditionally activated the UPRmt yielded a line, zc32, which robustly activated hsp-60∷gfp and hsp-6∷gfp at the nonpermissive temperature (25°) and weakly activated the reporters at the permissive temperature (20°) (Figure 1B). Larvae that hatched from mutant eggs placed at the nonpermissive temperature developed into slightly uncoordinated, hsp-60∷gfp-active adults with a compromised germline and very few progeny (Figure 1C); the latter is consistent with the detrimental role of mitochondrial stress on germline development. The ts mutation of zc32 segregated as simple Mendelian recessive mapping to a small region on chromosome II flanked by the markers R12C12 (−0.63 cM) and C56E9 (−0.17 cM) (see supplemental data at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). The phenotype was also uncovered by placing the mutant allele in trans to a deficiency (mnDf96, CGC strain SP788), suggesting that the mutation has significant loss-of-function features. The interval in question contains three genes whose products are predicted to function in mitochondria; however, the coding sequence of all three was identical in zc32 and N2 animals. Furthermore, RNAi inactivation of none of the 116 predicted genes in the interval phenocopied the mutation in wild-type animals nor did such RNAi affect the mutant phenotype of zc32 animals.

As the identity of the gene(s) responsible for the phenotype of zc32 remained obscure, we sought further evidence that the mutation selectively compromises mitochondrial function. Therefore, we compared the ability of zc32 animals to cope with mitochondrial stress or ER stress (as a reference) by inactivating genes whose products are important for either mitochondrial or ER homeostasis. At the permissive temperature, both wild-type and zc32 larvae developed into adult animals, whether exposed to spg-7(RNAi) (a mitochondrial protease), hsp-60(RNAi) (a mitochondrial chaperone), phb-2(RNAi) (a mitochondrial membrane protein assembly factor), or ire-1(RNAi) (a component of the UPRer, whose inactivation causes ER stress). At the nonpermissive temperature, zc32 mutant animals were selectively impaired in their ability to develop under RNAi that induces further mitochondrial stress, but their ability to cope with ER stress was comparable to the wild type (Figure 2). The above observations present a genetic argument that zc32 animals experience mitochondrial stress at the nonpermissive temperature and that they might be useful tools in identifying genes required for signaling the UPRmt.

ubl-5, a gene that functions in the UPRmt:

Using an arrayed RNAi library (Kamath et al. 2003), we sequentially inactivated annotated genes in the C. elegans genome in zc32 animals, searching for genes whose RNAi inhibited the hsp-60∷gfp reporter transgene at the nonpermissive temperature. To minimize the predicted negative affect of UPRmt inactivation on development and fertility of zc32 animals, we allowed embryonic development of the RNAi animals to proceed at the permissive temperature and switched the plates to the nonpermissive temperature for the final 24 hr before observing the animals. To identify the nonspecific effects of a given RNAi clone on animal health or reporter gene activity, we monitored, in parallel, the effects of RNAi on animals with a mutation, upr-1(zc6) X, that activates the UPRer reporter hsp-4∷gfp (Calfon et al. 2002). We sought genes whose RNAi selectively impaired the health of zc32 animals while selectively diminishing hsp-60∷gfp activity.

A systematic RNAi survey of all (2445) available genes on chromosome I identified numerous genes whose inactivation selectively impaired the health of zc32 animals. All but one of these were associated with activation of the hsp-60∷gfp reporter. As expected, most such genes encode known mitochondrial proteins whose inactivation promotes further mitochondrial misfolded protein stress (i.e., they encode chaperones, proteases, subunits of protein complexes, or components of the mitochondrial transcription or translational apparatus) (Yoneda et al. 2004; Hamilton et al. 2005). The selective negative effect of their inactivation on the health of zc32 animals is readily explained by inability of the mutant animals to cope with further mitochondrial misfolded protein stress (Figure 2). RNAi of one gene, lin-35, reproducibly attenuated hsp-60∷gfp expression but did not selectively compromise the health of zc32 animals, suggesting that the encoded protein, a C. elegans homolog of the retinoblastoma gene product, is not implicated in the endogenous UPRmt.

Inactivation of one gene, ubl-5, was associated both with decreased expression of the UPRmt reporter genes (Figure 3A) and with impaired development of zc32 animals (Figure 3B). The RNAi clone used in this screen contained a relatively large genomic fragment; therefore, to confirm that the phenotype observed was due to inactivation of ubl-5 (and not other genes on the same DNA fragment), we constructed a cDNA-based RNAi-feeding plasmid that contained only the coding region of ubl-5, which produced the same phenotype as the original genomic RNAi clone (Figure 3B, left). We also confirmed by Northern blotting the degradation of endogenous ubl-5 mRNA in the ubl-5(RNAi) animals (data not shown).

To examine the scope of ubl-5's role in the UPRmt, we compared the activity of hsp-60∷gfp in wild-type and ubl-5(RNAi) animals in which mitochondrial stress had been induced by inactivation of the mitochondrial chaperone HSP-60, protein assembly factor PHB-2, or the mitochondrial protease SPG-7. In each case, ubl-5(RNAi) diminished the expression of the hsp-60∷gfp reporter, as measured by GFP immunoblot (Figure 3C). Furthermore, ubl-5(RNAi) also lowered levels of stress-induced expression of endogenous hsp-6 and hsp-60 mRNA, an effect that was evident at both 72 and 96 hr after hatching in animals developing on ubl-5(RNAi) plates (Figure 3D).

To determine if the inhibitory effects of ubl-5(RNAi) on the UPRmt are a consequence of diminished expression of functional UBL-5, we sought to rescue the RNAi phenotype using a transgene resistant to the RNAi effects of C. elegans ubl-5. To this end, we exploited the fact that the homologous gene from C. briggsae encodes an identical protein; however, sequence divergence at the nucleic acid level was predicted to negate the effects of heterologous RNAi. This notion was supported by the observation that RNAi of C. briggsae ubl-5 had no phenotype in C. elegans (Figure 3, A and B, right). A UBL-5∷GFP-expressing transgene was constructed using the C. briggsae ubl-5 coding sequence (designated ubl-5Cb∷gfp). The C. briggsae transgene was immune to the C. elegans coding sequence ubl-5(RNAi), whereas expression of the synonymous C. elegans-based transgene ubl-5Ce∷gfp was inhibited in tissues susceptible to RNAi effects (supplemental Figure S1A at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

To determine if UBL-5Cb-GFP is a functional protein, we examined its ability to rescue the phenotype associated with loss of endogenous UBL-5 expression; the marked decrease in fertility of ubl-5(RNAi) observed in hypersensitive eri-1 (mg366) IV mutant animals maintained at 20° was corrected by the ubl-5Cb∷gfp transgene (supplemental Figure 1B at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). Next we determined if UBL-5Cb∷GFP can rescue the defect in the UPRmt imposed by C. elegans ubl-5(RNAi). We bred the rescuing transgene into a background containing the zc32 mutation (to activate the UPRmt) and the hsp-60∷gfp transgene (to report on the activation). The GFP protein expressed by the reporter transgene is smaller than the UBL-5-GFP fusion protein expressed from the rescuing transgene and the two are readily distinguished by their mobility on SDS–PAGE. C. elegans ubl-5(RNAi) markedly diminished the expression of the reporter in N2 animals, as noted above (Figure 3C); however, the inhibitory effect of ubl-5(RNAi) on the UPRmt was rescued by the UBL-5Cb-GFP transgene (Figure 3E). These experiments implicate UBL-5 protein in the UPRmt.

ubl-5(RNAi) adversely affects the protein-folding environment in the mitochondria:

While the observations noted above indicate that ubl-5(RNAi) attenuates signaling in the UPRmt, they do not identify the step in the process at which the gene acts. If UBL-5 is active in the UPRmt afferent limb, ubl-5(RNAi) is predicted to enhance mitochondrial misfolded protein stress and to promote intrinsic defects in mitochondrial function and structure. However, if ubl-5(RNAi) suppresses the UPRmt upstream by reducing the load of unfolded/misfolded proteins in the mitochondrial matrix, the mitochondria of ubl-5(RNAi) animals would not be expected to exhibit intrinsic defects in function or structure (see Figure 1A).

To address this issue, we began by examining mitochondrial morphology, making use of myo-3∷gfpmt transgenic animals whose body-wall muscles express GFP tagged with a mitochondrial import signal (GFPmt). In wild-type myo-3∷gfpmt transgenic animals, the GFPmt signal presents a pattern of neatly stacked arrays of mitochondria aligned with the muscle fibers (Labrousse et al. 1999) (Figure 4A). The mitochondria of spg-7(RNAi), hsp-60(RNAi), and phb-2(RNAi) animals are thicker and often fragmented and have brighter GFPmt signals than animals exposed to mock RNAi treatment or to ire-1(RNAi) (which, by causing ER stress, serves as a control for nonspecific stressful effects of mitochondrial perturbations). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that inactivation of genes required for protein folding and assembly in the mitochondrial matrix indirectly alters organelle morphology (although a direct role for hsp-60, spg-7, and phb-2 in maintaining mitochondrial morphology cannot be excluded). Importantly, animals raised on ubl-5(RNAi) have a GFPmt pattern that resembles mitochondrially stressed animals (Figure 4A). The latter observation is consistent with compromised mitochondrial homeostasis in the ubl-5(RNAi) animals and does not support upstream suppression of the UPRmt by ubl-5 inactivation.

Whereas adult N2 animals that developed from larvae raised on ubl-5(RNAi) had a roughly normal brood size, zc32 embryos raised to adulthood at the nonpermissive temperature on ubl-5(RNAi) plates had very few progeny (Figure 3B). To determine if these negative interactions of ubl-5(RNAi) extend to other conditions associated with enhanced mitochondrial stress, we took advantage of the observation that high-level expression of mitochondrially targeted GFP (myo-3∷gfpmt) markedly attenuates an animal's ability to cope with further mitochondrial stress whereas expression of even higher levels of cytoplasmic GFP (myo-3∷gfpcyt) is less perturbing (Figure 4B). These observations are consistent with the fact that GFP is slow to fold and requires significant assistance by chaperones (Wang et al. 2002). Thus, evidence of a selective negative interaction with a transgene expressing GFPmt suggests that a given genetic lesion is associated with mitochondrial stress. We found that ubl-5(RNAi) adversely affected growth and development of myo-3∷gfpmt animals but had no such negative effect on myo-3∷gfpcyt animals expressing GFP in the cytosol (Figure 4, B and D). Furthermore, ubl-5(RNAi) compromised fertility of ges-1∷gfpmt animals expressing GFPmt in their intestinal cells, but had no such negative effect on ges-1∷gfpcyt animals expressing higher levels of cytosolic GFP (Figure 4, C and D).

To further examine the effect of ubl-5 inactivation on the protein-folding environment in the mitochondrial matrix, we followed the fate of marker mitochondrial proteins that normally assemble into multi-subunit complexes in the mitochondrial matrix. As antisera to C. elegans mitochondrial proteins were not available, we exploited the fact that some abundant mitochondrial proteins are naturally tagged with a covalently bound biotin moiety and can be detected by their reactivity to enzyme-linked streptavidin following denaturing SDS–PAGE and ligand blotting. In mammalian mitochondria, the α-subunits of 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (αMCC) and propionyl-CoA carboxylase (αPCC) account for most of the biotinylated proteins detected by this ligand-blot assay (Baumgartner et al. 2001). In C. elegans, too, a ligand blot using HRP-linked strepavidin yielded a major labeled species of ∼75 kDa, consistent with the predicted size of αPCC (F27D9.5, predicted 79.7 KDa), αMCC (F32B6.2, predicted 73.7 kDa), or both. The biotinylated species were enriched in the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 5A) and were distinct in size from the major E. coli biotinylated proteins detected by the same assay (data not shown) (as worms are fed E. coli, it was important to deal with the potentially confounding effects of contaminating bacterial biotinylated proteins on this assay).

Both αPCC and αMCC assemble into high-molecular-weight complexes in the mitochondrial matrix (Chloupkova et al. 2000), and velocity gradient centrifugation showed a peak of biotinylated proteins with a predicted mass of ∼800 kDa, consistent with the expected mass of a dodecamer of α- and β-subunits of MCC or PCC (Figure 5B, top). The peak of biotinylated protein was shifted toward lighter fractions in animals in which mitochondrial protein folding was compromised by hsp-60(RNAi) and a similar shift was also observed in myo-3∷gfpmt animals, consistent with impaired complex formation or turnover in stressed animals. In unstressed animals, ubl-5(RNAi) did not markedly affect the distribution of biotinylated proteins in the gradient (although a trend toward a lighter peak was noted; data not shown). However, compounding the stress-inducing myo-3∷gfpmt transgene with ubl-5(RNAi) shifted the peak to lighter fractions (Figure 5B, bottom-most panel), indicating that loss of UBL-5 adversely affects the protein-folding environment in mitochondrially stressed worms. These experiments support the hypothesis that ubl-5(RNAi) leads to a state of enhanced mitochondrial misfolded protein stress by compromising the counteractive response to such stress.

Mitochondrial stress is associated with increased levels of UBL-5 in the nucleus:

To gain further insight into how UBL-5 might contribute to signaling in the UPRmt, we sought to localize the protein in unstressed and stressed animals. Unlike other ubiquitin-like proteins whose C termini engage in isopeptide bond formation with various targets, UBL-5 remains covalently unattached (Lüders et al. 2003). A high-resolution NMR structure of human UBL-5 indicates that despite a high level of overall structural similarity to ubiquitin and SUMO, the C terminus of UBL-5 is unavailable for isopeptide bond formation (McNally et al. 2003). Furthermore, the presence of an uncleaved C-terminal epitope tag on UBL-5 is compatible with rescue of the lethal phenotype associated with deletion of the endogenous gene in Schizosaccharoumyces pombe (Yashiroda and Tanaka 2004). Therefore, we studied transgenic animals in which UBL-5 protein, expressed from its endogenous promoter, was tagged by GFP at the C terminus, ubl-5∷gfp.

Several integrated transgenic lines of ubl-5∷gfp were produced and they exhibited similar distribution of the transgene reporter. UBL-5∷GFP was expressed at low levels in most tissues of the adult, with slightly more conspicuous staining in the intestine, especially its posterior segment, and in the pharynx. Viewed at high magnification, the UBL-5∷GFP signal appeared to be distributed throughout the intestinal cell (Figure 6A). Mitochondrial stress, induced by spg-7(RNAi), hsp-60(RNAi), or phb-2(RNAi), increased reporter levels, whereas induction of ER stress by ire-1(RNAi) did not (Figure 6A). In the mitochondrially stressed animals, the UBL-5∷GFP signal was notably concentrated in the nuclei, as revealed by the overlap between the GFP signal and the H33258 DNA stain (Figure 6A) and by measurements of the ratio of the nuclear-to-cytosolic fluorescence in individual intestinal cells (Figure 6B). These stress-dependent changes in UBL-5∷GFP expression were most conspicuous in intestinal cells in which hsp-60 and hsp-6 activation by mitochondrial stress is also most apparent (Yoneda et al. 2004). These observations are consistent with UBL-5 acting at a nuclear step of the UPRmt.

DISCUSSION

Using an unbiased method of RNAi-mediated sequential gene inactivation, we screened C. elegans chromosome I for genes whose loss of function interferes with the UPRmt. Inactivation of ubl-5, a gene encoding a small ubiquitin-like protein, was discovered to attenuate both UPRmt reporters (hsp-60∷gfp, hsp-6∷gfp) and endogenous target genes of the response. Genetic, morphological, and biochemical evidence indicated that ubl-5(RNAi) compromises the protein-folding environment in the mitochondria and adversely affects mitochondrial morphology. These observations are most consistent with UBL-5's participation in the afferent limb of the UPRmt, which couples misfolded protein stress to the activation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial chaperones. Diminished activity of this afferent limb leads to a relative deficiency in chaperone expression and to higher levels of mitochondrial stress in ubl-5(RNAi) animals.

Mitochondrial stress leads to accumulation of UBL-5∷GFP in nuclei, a finding consistent with a role for the protein in executing a late step in activated gene expression in the UPRmt. The increase in the nuclear UBL-5∷GFP signal reflects in part an increase in protein levels, which correlates to transcriptional activation in stressed animals (data not shown). More importantly, mitochondrial stress promotes a net accumulation of the protein in the nucleus (evident after adjusting for differences in UBL-5∷GFP protein levels in unstressed and stressed animals). These observations suggest that UBL-5 is a target of both transcriptional and post-transcriptional signals in mitochondrially stressed cells. Components of the analogous UPRer are also regulated both post-transcriptionally and transcriptionally (Harding et al. 2000; Calfon et al. 2002), suggesting that this is a general mechanism for amplifying stress responses. We expect that the identification of other components of the UPRmt will help elucidate the signals that convey UBL-5 to the nucleus in stressed cells.

UBL-5 is a highly conserved protein with homologs in all known eukaryotes. The budding yeast homolog Hub1p has been implicated in polarized morphogenesis, a process that appears to depend on interactions with proteins that function at the bud neck (Dittmar et al. 2002). In fission yeast, by contrast, Hub1p is nuclear, forms a complex with the splicing factor Snu66, and plays an essential role in pre-mRNA splicing (Wilkinson et al. 2004; Yashiroda and Tanaka 2004). The involvement of UBL-5 in splicing is also consistent with reports of the formation of a complex between the cdc2-like kinases (CLKs) and mammalian UBL-5; CLKs are known to phosphorylate SR proteins that interact with pre-mRNA (Kantham et al. 2003).

We did not observe a general defect in pre-mRNA splicing in ubl-5(RNAi) animals and RNAi of CLK homologs in C. elegans did not phenocopy ubl-5(RNAi) (data not shown). These negative results are not definitive; RNAi may be less effective at eliminating gene function than the temperature-sensitive alleles of S. pombe HUB1 in which the general splicing defect was observed (Wilkinson et al. 2004; Yashiroda and Tanaka 2004). Therefore, the nuclear localization of UBL-5∷GFP remains consistent with a role for UBL-5 in a regulated splicing event required for activated gene expression in the UPRmt. But it is also possible that UBL-5 is implicated in other aspects of gene expression, such as regulated transcription. The latter possibility is favored by the observations that UBL-5 interacts physically with a transcription factor whose encoding gene is required for signaling the UPRmt in worms (C. M. Haynes, unpublished observations).

A unifying explanation for the diversity of observations made of cells and organisms lacking UBL-5 may not be required, as the protein may contribute to processes lacking a shared biological theme. The observation that hub1Δ yeast are respiratory competent suggests that the protein's role in the UPRmt might not be conserved in budding yeast (a species in which a UPRmt has not been demonstrated to exist). Nor do we know if UBL-5's role in the UPRmt is conserved in other metazoans. However, in regard to the latter, it is intriguing to note that UBL-5 mRNA is relatively abundant in mitochondria-rich human tissues, such as heart, skeletal muscle, liver, and kidney (Friedman et al. 2001), and that polymorphisms in UBL-5 have been linked to the metabolic syndrome of obesity and diabetes (Jowett et al. 2004), a syndrome in which mitochondrial homeostasis plays an important role.

Acknowledgments

We thank Art Horwich and Wayne Fenton (Yale University); Frank Frerman (University of Colorado); Catherine Clarke and Tanya Jonassen (University of California at Los Angeles); Jodi Nunnari (University of California at Davis); Janet Shaw (University of Utah); Terry McNally (Abbott Labs); Chi Yun, Scott Clark, and Gabriele Campi (Skirball Institute) for advice; and the C. elegans Genetics Center for strains. This work was supported by the Ellison Medical Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants ES08681 and DK47119 to D.R. and F32-NS050901 to C.M.H.

References

- Artal-Sanz, M., W. Y. Tsang, E. M. Willems, L. A. Grivell, B. D. Lemire et al., 2003. The mitochondrial prohibitin complex is essential for embryonic viability and germline function in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 32091–32099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, M. R., S. Almashanu, T. Suormala, C. Obie, R. N. Cole et al., 2001. The molecular basis of human 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 107: 495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal, M. F., 2005. Mitochondria take center stage in aging and neurodegeneration. Ann. Neurol. 58: 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biaszczak, A., C. Georgopoulos and K. Liberek, 1999. On the mechanism of FtsH-dependent degradation of the sigma 32 transcriptional regulator of Escherichia coli and the role of the Dnak chaperone machine. Mol. Microbiol. 31: 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau, B., 1993. Regulation of the Escherichia coli heat-shock response. Mol. Microbiol. 9: 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau, B., and A. L. Horwich, 1998. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell 92: 351–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfon, M., H. Zeng, F. Urano, J. H. Till, S. R. Hubbard et al., 2002. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415: 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chloupkova, M., K. Ravn, M. Schwartz and J. P. Kraus, 2000. Changes in the carboxyl terminus of the beta subunit of human propionyl-CoA carboxylase affect the oligomer assembly and catalysis: expression and characterization of seven patient-derived mutant forms of PCC in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. Metab. 71: 623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotto, J. J., and R. I. Morimoto, 1999. Stress-induced activation of the heat-shock response: cell and molecular biology of heat-shock factors. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 64: 105–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, G. A., C. R. Wilkinson, P. T. Jedrzejewski and D. Finley, 2002. Role of a ubiquitin-like modification in polarized morphogenesis. Science 295: 2442–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, A. G., R. S. Kamath, P. Zipperlen, M. Martinez-Campos, M. Sohrmann et al., 2000. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature 408: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J. S., B. F. Koop, V. Raymond and M. A. Walter, 2001. Isolation of a ubiquitin-like (UBL5) gene from a screen identifying highly expressed and conserved iris genes. Genomics 71: 252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, B., Y. Dong, M. Shindo, W. Liu, I. Odell et al., 2005. A systematic RNAi screen for longevity genes in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 19: 1544–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, H., I. Novoa, Y. Zhang, H. Zeng, R. C. Wek et al., 2000. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 6: 1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, H. P., M. Calfon, F. Urano, I. Novoa and D. Ron, 2002. Transcriptional and translational control in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 18: 575–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl, F. U., and M. Hayer-Hartl, 2002. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295: 1852–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwich, A. L., E. U. Weber-Ban and D. Finley, 1999. Chaperone rings in protein folding and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 11033–11040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen, T., B. N. Marbois, K. F. Faull, C. F. Clarke and P. L. Larsen, 2002. Development and fertility in Caenorhabditis elegans clk-1 mutants depend upon transport of dietary coenzyme Q8 to mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 45020–45027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowett, J. B., K. S. Elliott, J. E. Curran, N. Hunt, K. R. Walder et al., 2004. Genetic variation in BEACON influences quantitative variation in metabolic syndrome-related phenotypes. Diabetes 53: 2467–2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R. S., A. G. Fraser, Y. Dong, G. Poulin, R. Durbin et al., 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421: 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantham, L., L. Kerr-Bayles, N. Godde, M. Quick, R. Webb et al., 2003. Beacon interacts with cdc2/cdc28-like kinases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304: 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, R. J., D. Scheuner, M. Schroder, X. Shen, K. Lee et al., 2002. The unfolded protein response in nutrient sensing and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrousse, A. M., M. D. Zappaterra, D. A. Rube and A. M. van der Bliek, 1999. C. elegans dynamin-related protein DRP-1 controls severing of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol. Cell 4: 815–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer, T., M. Kaser, C. Klanner and K. Leonhard, 2001. AAA proteases of mitochondria: quality control of membrane proteins and regulatory functions during mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 29: 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm, D., O. Eriksson and L. Korhonen, 2004. Mitochondrial proteins in neuronal degeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321: 753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist, S., and E. A. Craig, 1988. The heat-shock proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22: 631–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüders, J., G. Pyrowolakis and S. Jentsch, 2003. The ubiquitin-like protein HUB1 forms SDS-resistant complexes with cellular proteins in the absence of ATP. EMBO Rep. 4: 1169–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak, S. J., C. Y. Yun, S. Oyadomari, I. Novoa, Y. Zhang et al., 2004. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 18: 3066–3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinus, R. D., G. P. Garth, T. L. Webster, P. Cartwright, D. J. Naylor et al., 1996. Selective induction of mitochondrial chaperones in response to loss of the mitochondrial genome. Eur. J. Biochem. 240: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally, T., Q. Huang, R. S. Janis, Z. Liu, E. T. Olejniczak et al., 2003. Structural analysis of UBL5, a novel ubiquitin-like modifier. Protein Sci. 12: 1562–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. I., M. L. Whitfield, N. D. Trinklein, R. M. Myers, P. O. Brown et al., 2004. Diverse and specific gene expression responses to stresses in cultured human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 2361–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert, W., 1997. Protein import into mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66: 863–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijtmans, L. G., L. de Jong, M. Artal Sanz, P. J. Coates, J. A. Berden et al., 2000. Prohibitins act as a membrane-bound chaperone for the stabilization of mitochondrial proteins. EMBO J. 19: 2444–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil, C., and P. Walter, 2001. Intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus: the unfolded protein response in yeast and mammals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13: 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, W. Y., L. C. Sayles, L. I. Grad, D. B. Pilgrim and B. D. Lemire, 2001. Mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiency in Caenorhabditis elegans results in developmental arrest and increased life span. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 32240–32246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano, F., M. Calfon, T. Yoneda, C. Yun, K. Duke et al., 2002. A survival pathway for C. elegans with a blocked unfolded protein response. J. Cell Biol. 158: 639–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voos, W., and K. Rottgers, 2002. Molecular chaperones as essential mediators of mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1592: 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. D., C. Herman, K. A. Tipton, C. A. Gross and J. S. Weissman, 2002. Directed evolution of substrate-optimized GroEL/S chaperonins. Cell 111: 1027–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C. R., G. A. Dittmar, M. D. Ohi, P. Uetz, N. Jones et al., 2004. Ubiquitin-like protein Hub1 is required for pre-mRNA splicing and localization of an essential splicing factor in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 14: 2283–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C., 1995. Heat shock transcription factors: structure and regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 11: 441–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiroda, H., and K. Tanaka, 2004. Hub1 is an essential ubiquitin-like protein without functioning as a typical modifier in fission yeast. Genes Cells 9: 1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda, T., C. Benedetti, F. Urano, S. G. Clark, H. P. Harding et al., 2004. Compartment specific perturbation of protein folding activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. J. Cell Sci. 117: 4055–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q., J. Wang, I. V. Levichkin, S. Stasinopoulos, M. T. Ryan et al., 2002. A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 21: 4411–4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]