Abstract

An RNA virus population does not consist of a single genotype; rather, it is an ensemble of related sequences, named quasispecies 1–4. Quasispecies arise from rapid genomic evolution powered by the high mutation rate of RNA viral replication 5–8. While a high mutation rate is dangerous for a virus as it results in nonviable individuals, it has been hypothesized that high mutation rates create a “cloud” of potentially beneficial mutations at the population level, which afford the viral quasispecies a greater probability to evolve and adapt to new environments and challenges during infection 4,9–11. Importantly, mathematical modelling predicts that the viral quasispecies is not simply a collection of diverse mutants but a group of interactive variants, which together contribute to the characteristics of the population 4,12. In this view, viral populations, rather than individuals, are the target of evolutionary selection 4,12. To test this hypothesis we examined whether limiting genomic diversity affects viral pathogenesis. We find that poliovirus carrying a high fidelity polymerase replicates at wildtype levels but generates less genomic diversity and is unable to adapt to adverse growth conditions. In infected animals, the reduced viral diversity led to loss of neurotropism and an attenuated pathogenic phenotype. Strikingly, expanding quasispecies diversity of the high fidelity virus by chemical mutagenesis prior to infection restored neurotropism and pathogenesis. Analysis of viruses isolated from brain provides direct evidence for complementation between members within the quasispecies, indicating that selection indeed occurred at the population level rather than on individual mutants. Our study provides direct evidence for a fundamental prediction of the quasispecies theory and establishes a compelling link between mutation rate, population dynamics and pathogenesis.

To examine the biological role of viral quasispecies we searched for viruses carrying a polymerase with enhanced fidelity, which should decrease genomic diversity and restrict quasispecies complexity. To this end, we isolated poliovirus resistant to ribavirin (Supplementary Fig. S1), a mutagen that increases mutation frequency of poliovirus replication above the tolerable error threshold and drives the virus into viral extinction 13,14. The ribavirin-resistant mutant replicated efficiently in the presence of ribavirin, producing over 300-fold more virus than wildtype (Supplementary Fig. S2a). The ribavirin-resistant phenotype is determined by a single point mutation, Gly-64 to Ser (G64S), within the finger domain of the viral polymerase 15. Interestingly, the same mutation was independently isolated in another screen for ribavirin-resistant polioviruses 16, suggesting that there are limited mechanistic avenues to overcome the mutagenic effects of ribavirin.

Based on genetic evidence, it was proposed that ribavirin resistance relies on a “super accurate”, high fidelity polymerase 16. Thus, a lower error rate would reduce the risk posed by this mutagen of exceeding the tolerable error threshold, resulting in viral extinction 13,14. To further examine this possibility, we determined whether G64S viral populations generate fewer variants relative to the original genome, by direct sequencing of viral isolates within the population. Indeed, G64S mutant populations had 6-fold fewer mutations than wildtype (~0.3 mutations/genome for G64S compared to ~1.9 mutations/genome for wildtype) (Table 1), indicating that G64S viral populations are genetically more homogenous. We also assessed population diversity by determining the proportion of a genetic marker present in wildtype and G64S populations. Poliovirus RNA replication is strongly inhibited by the presence of 2 mM guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl); however, mutations that confer resistance to GdnHCl (guar) have been identified 17,18. In good agreement with our sequencing data and with previous observations 16, wildtype virus stocks had about 3 to 4-fold more guar viruses than the restricted G64S quasispecies (Table 1). Importantly, biochemical studies directly confirmed that the G64S RNA polymerase has increased fidelity relative to wildtype 19. Although Gly-64 is remote from the catalytic centre, this residue participates in a network of hydrogen bonds 15 that influences the conformation of Asp-238, a residue that is absolutely critical for nucleotide selection 19,20.

Table 1.

Genomic diversity for wildtype, G64S and G64SeQS populations

| Virus | Total number of mutationsa | Mutation per genome | guar variantsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| wildtype | 13/50,700 | 1.91 | 62 ± 6 |

| G64S | 2/50,700 | 0.31 | 22 ± 8 |

| G64SeQS | 14/50,700 | 2.06 | 56 ± 6 |

| c | |||

| wildtypeb | 12/48,588 | 1.84 | ND |

| G64Sb | 6/69,000 | 0.65 | ND |

| G64SeQS-b | 6/50,700 | 0.88 | ND |

Number of mutations observed over the total number of nucleotides sequenced. To determine the mutation frequency in each poliovirus population, 24 independent poliovirus cDNA clones were obtained. Poliovirus cDNAs were generated by RT-PCR from plaque isolated viral RNA. A significant difference was observed between WT and G64S (p<0.002) based on a Mann Whitney U test. In contrast, no significant difference was observed between WT and G64SeQS (p<0.222).

Per 106 plaque-forming units (PFU), Mean ± s.d. of 6 experiments. Significance testing yielded p<0.001 by ANOVA.

wildtypeb, G64Sb, G64SeQS-B re-isolated from infected brain. Number of Guar variants was not determined.

The identification of G64S as a mutation that restricts genome diversity in viral populations allowed us to critically examine the quasispecies hypothesis. Given that Gly-64 is highly conserved 21, we initially examined whether increased fidelity was achieved at the expense of viral replication rate. One-step growth curves and northern blot analysis of genomic RNA synthesis indicate that wildtype and G64S replicated at very similar rates and levels (Supplementary Figs. S2b and S2c). Furthermore, poliovirus replicons carrying the G64S allele replicated with identical efficiency to wildtype (Supplementary Fig. S2d). We thus conclude that the G64S mutation confers higher fidelity without significant reduction of the overall RNA replication efficiency.

The greater sequence heterogeneity, characteristic of viruses replicating close to the tolerable error threshold, generates diverse quasispecies, thereby providing a reservoir of mutations that enable virus adaptation to changing environments encountered during infection 4,11. To test this postulate we compared the adaptability of wildtype and G64S-restricted quasispecies to an experimental environmental stress created by the presence of the poliovirus inhibitor GdnHCl. As expected, the wildtype population adapted at significantly faster rates than G64S to the new environment (Supplementary Fig. S3c). We also examined the evolutionary progression of wildtype and G64S-restricted quasispecies by determining the spontaneous accumulation of guar mutants in populations grown under no selective pressure. The higher fidelity polymerase G64S is restricted in its ability to build a reservoir of potentially beneficial mutations (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Furthermore, the increase in polymerase fidelity decreases viral fitness as defined by the inability of G64S to effectively compete with wildtype under adverse growth conditions (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Taken together, these experiments support the notion that the diversity of a quasispecies is essential for adapting to and surviving new selective pressures in changing environments.

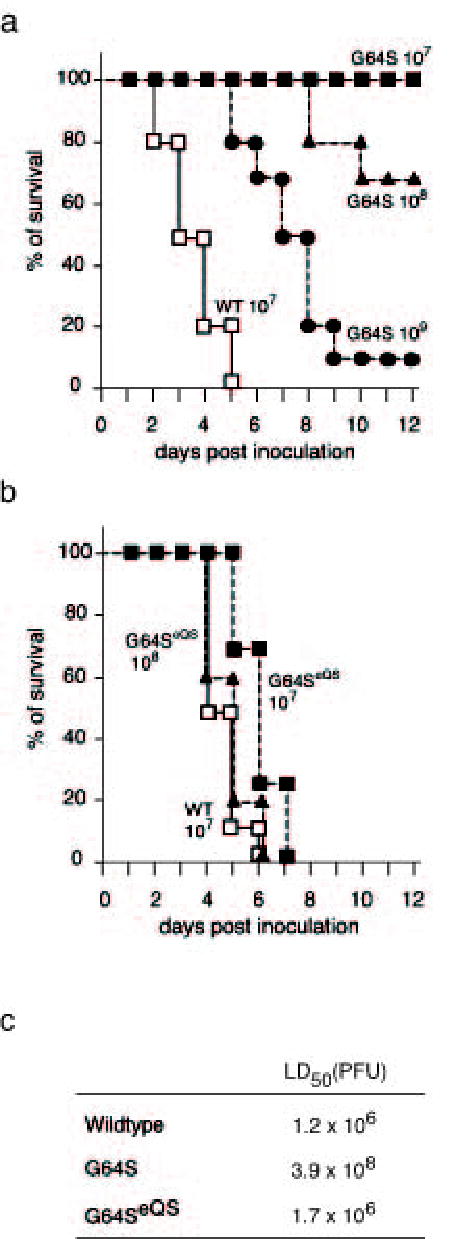

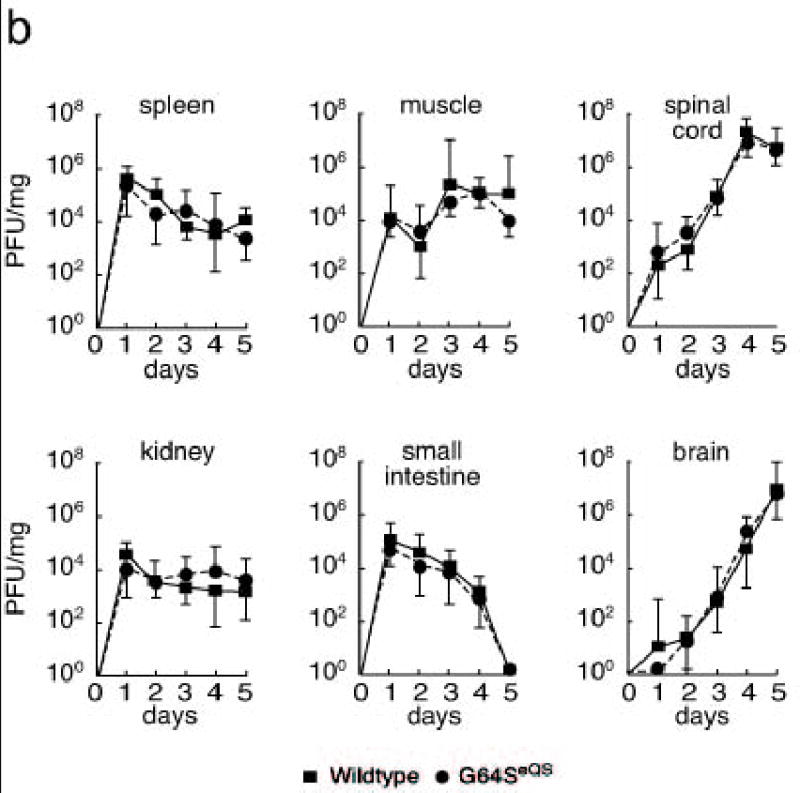

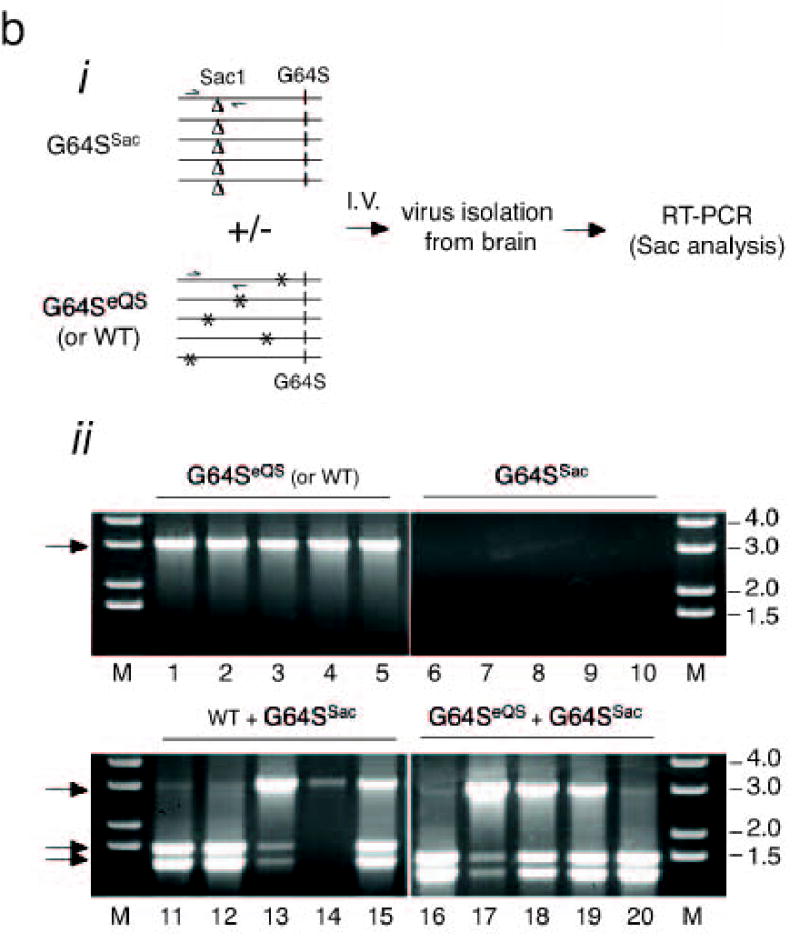

The major challenges to viral survival occur during its interactions with the host. During infection, viruses struggle with host-to-host transmission, host defense mechanisms, diverse cellular environments in different tissues, and anatomic restrictions such as the blood-brain barrier. The outcome of these multiple selective pressures determines tissue tropism and ultimately, the pathogenic outcome of an infection. To evaluate whether restricting population diversity affects the biological course of a viral infection, G64S was inoculated in susceptible mice by intramuscular injection, which allows poliovirus to quickly access the central nervous system (CNS) by axonal retrograde transport 22. G64S virus presented a highly attenuated phenotype, where onset of paralysis was delayed and observed only at very high viral doses (Fig. 1a). Accordingly, the 50% lethal dose for G64S was more than 300-fold higher than for wildtype (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, intravenous inoculation indicated that the high fidelity G64S virus exhibits a restricted tissue tropism. While both wildtype and G64S were readily isolated over several days from spleen, kidney, muscle, and small intestine, the mutant was unable to establish infection and effectively replicate in the spinal cord and brain (Fig. 2a), despite their being major sites of wildtype poliovirus replication.

Figure 1.

A restricted quasispecies of poliovirus is less neuropathogenic. a–b, Percentage of mice surviving intramuscular injection of different doses (107, 108, 109 PFU) of the narrow G64S (a) or the expanded G64SeQS populations (b) as compared to wildtype (WT, open symbols, only one dose, 107 PFU is shown). The number of mice per group was 20 (n=20). The differences observed between WT (107 PFU) and G64S (107, 108, 109 PFU) or the expanded G64SeQS (107 PFU) are statistically significant (P<0.001). In contrast, no statistically significant difference was observed between WT (107 PFU) and G64SeQS (108 PFU) (p>0.5). c, Calculation of LD50 values for each viral stock using the Reed and Muench method.

Figure 2.

Genomic diversity in a quasispecies is critical in viral tissue tropism and pathogenesis. a–b, Virus titers in PFU/gram from tissue of mice infected intravenously with the wildtype virus population (squares), the narrow G64S quasispecies (circles in a) or the artificially expanded G64SeQS quasispecies (circles in b). Mean values ± s.d. of 3 experiments are shown.

The attenuated phenotype observed for G64S could stem from the restricted nature of its quasispecies diversity or could be the consequence of a specific RNA replication defect caused by the G64S mutation in vivo. To distinguish between these possibilities we created an artificially expanded quasispecies that retains the G64S mutation in the polymerase (Supplementary Fig. S4). Treatment of viral stocks with chemical mutagens (ribavirin and 5-fluorouracil) increased the number of mutations in the G64S genome (G64SeQS, expanded quasispecies) to wildtype levels, as determined by direct sequencing and by the number of guar viruses present in the population (Table 1). Importantly, of more than 25 independent clones sequenced, all viruses in the G64SeQS population conserved the G64S substitution (not shown). Notably, the more diverse G64SeQS viral population displayed a significant increase in neuropathogenesis, as the LD50 of the mutagenized population was very similar to wildtype (Fig. 1b and 1c). Furthermore, the tissue distribution of G64SeQS was indistinguishable from that observed for wildtype (Fig. 2b). Importantly, sequencing of 24 isolates obtained directly from brain tissues of mice infected with G64SeQS confirmed that the G64S substitution was still present in all. We thus conclude that the G64S mutation does not in itself preclude replication in neuronal tissues.

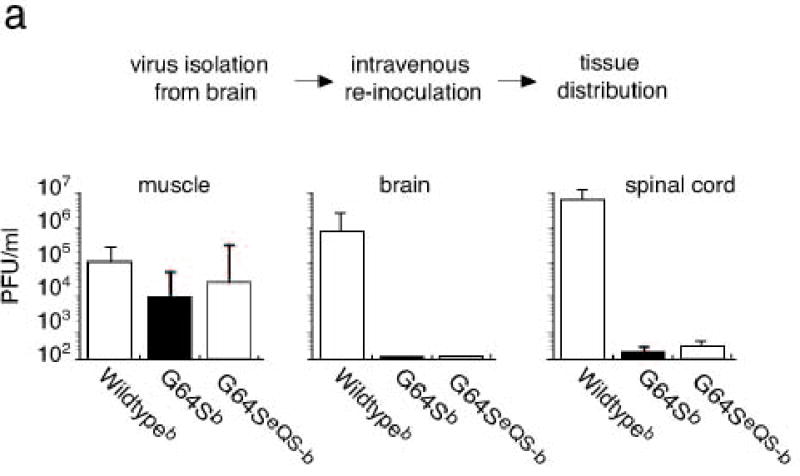

We next considered whether the artificial expansion of G64SeQS enhanced pathogenicity by generating specific neurotropic mutations. In the simplest model, viruses carrying these advantageous mutations could selectively enter and replicate in the CNS. Accordingly, we re-isolated G64SeQS from brains of infected mice and analyzed them by direct sequencing. Strikingly, the sequence of the viral RNA from brain was indistinguishable from the original inoculated G64SeQS genome, as well as from the genomes of wildtype (apart from the 64 position) or G64S (not shown). Because direct sequencing of the viral RNA population only reveals the predominant consensus sequences of the quasispecies, we also sequenced 72 independently cloned viruses isolated from infected brains. Again, no recurring mutations were detected, suggesting that a discrete set of mutations was not selected in the neurotropic virus population. Since the inability to detect a specific set of mutations by direct sequencing could indicate that a very large set of mutations within the G64SeQS is neurotropic, we next employed a functional assay to analyse the viral populations isolated from infected brains. Thus, if infection of the mouse brain is caused by selection of a neurovirulent set of G64S variants, isolation of this population and subsequent re-inoculation should result in neuropathogenesis. Accordingly, we intravenously re-inoculated virus populations obtained from brains of animals infected with G64SeQS, as well as with wildtype and G64S controls. Strikingly, while wildtype virus remained neurotropic, G64SeQS isolated from brain (G64SeQS-b) was no longer able to infect the CNS (Fig. 3a). This result does not support the idea that a set of neurotropic mutations determines the pathogenic characteristics of G64SeQS. Notably, the G64SeQS-b and G64Sb populations had 2 to 3-fold fewer mutations than wildtypeb and the original artificially expanded quasispecies G64SeQS (Table 1), indicating that G64SeQS-b lost diversity during replication in vivo. Our results are not consistent with the model that expanding the quasispecies repertoire of G64SeQS enhances pathogenesis by generating a defined set of neurotropic mutations. Instead, they suggest a more complex model whereby a generalized increase in sequence diversity determines pathogenesis.

Figure 3.

Cooperative interactions among members of the virus population link quasispecies diversity with pathogenesis. a, Subpopulations of viruses isolated from brain of infected mice cannot re-establish CNS infection if the diversity of the quasispecies is restricted. Virus titers (PFU/g) from muscle, brain and spinal cord of mice infected intravenously for 4 days with 107 PFU viruses isolated from brains of infected animals with wildtypeb, G64Sb, G64seQS-b. On top, schematic representation of the protocol of re-inoculation is shown. b, Neurotropic virus populations facilitate entry and replication of a non-neurotropic virus into the CNS. i) schematic representation of an in vivo complementation experiment. G64SSac is a narrow quasispecies carrying a higher fidelity polymerase (G64S allele) and a silent mutation that introduces a Sac I site at nucleotide 1906 within the capsid region. This neutral genetic marker can be used as “bar-code”. Mice were infected intravenously with either G64SSac alone (2x108 PFU per animal) or co-injected with wildtype (WT) or G64SeQS at 1:1 ratios (108 PFU each virus per animal). Viruses were re-isolated from brain tissues, through infection of HeLa cells, and their RNA was analyzed by RT-PCR. ii) All PCR products were digested with Sac I prior agarose gel electrophoresis analysis. DNA obtained from wildtype or G64SeQS viruses are not digested by Sac I (~3 kb fragment); whereas the PCR product from the G64SSac virus generated two smaller bands (~1450 and 1350 kb) when digested with Sac I. On top of lanes virus injected into each mouse are indicated. Each lane corresponds to one infected mouse. Arrows on the left indicate full-length RT-PCR products and Sac1 digested PCR fragments. DNA markers (kb) are shown (M).

In contrast to classic genetic concepts suggesting that evolution occurs through the selection of individual viruses, the quasispecies theory proposed, based on theoretical considerations, that evolution occurs through selection of interdependent viral subpopulations4,9,10. This alternative model could explain our results. Thus, the interplay between different variants within the quasispecies could facilitate entry and replication of the virus population in the CNS. To test this model, we examined the ability of a non-neurotropic virus population carrying an identifier bar-code (G64SSac) to infect the CNS, either by itself or upon co-infection with either of two neurotropic populations: wildtype or the expanded G64SeQS. G64SSac carries the G64S allele that restricts genome diversity and a neutral Sac I restriction site that can be used to identify its RNA (Supplementary Fig. S6). After intravenous inoculation, viruses were isolated from the brain and analysed by RT-PCR and Sac I digestion. As expected, while wildtype or G64SeQS alone were readily isolated from brain, G64SSac was unable to infect either brain (Fig. 3b ii, upper panel and Supplementary Fig. S6b), or spinal cord (not shown). In striking contrast, G64SSac virus was isolated from the brain tissue of every infected mouse if co-inoculated with either wildtype or G64SeQS (Fig. 3b ii, lower panel). To confirm this observation we cloned and analyzed individual viruses from brain homogenates obtained from infected mice. Approximately 50% of the viruses isolated from brain corresponded to G64SSac (Supplementary Table S1). These data indicate that there is a positive interaction between different variants within the population so that some variants allow others to enter the brain, as anticipated by the quasispecies theory.

Our study shows that increasing the fidelity of poliovirus replication has a dramatic impact on viral adaptation and pathogenicity. These findings, alongside previous observations that an increase in error-rate led to error-catastrophe and viral extinction 23–25, suggest that the viral mutation rate is finely tuned and has likely been optimized during evolution of the virus. Survival of a given viral population depends on the balance between replication fidelity, which ensures the transmission of its genetic makeup, and genomic flexibility, which allows build up of a reservoir of individual variants within the population that facilitates adaptation to changing environmental conditions. Whereas too many mutations per genome can bring a viral population to extinction 13,14; too few mutations can cause extinction by rendering the virus unable to survive both changes in the environment and “bottlenecks”, such as replication in different tissues or transmission from individual to individual. Strikingly, we find that diversity of the quasispecies per se rather than selection of individual adaptive mutations correlates with enhanced pathogenesis. Our observation of cooperative interactions between different individuals within the quasispecies provides a rationale for the role of quasispecies diversity in infectivity. For instance, certain variants within the population may facilitate the colonization of the gut, another set of mutants may serve as immunological decoys that trick the immune system and yet another subpopulation may facilitate crossing the blood-brain barrier. Hence, while G64SeQS-b virus re-isolated from brain was highly pathogenic when injected directly into the CNS (Supplementary Fig. S5), it was unable to infect the CNS after intravenous inoculation (Fig. 4a). Thus, maintaining the complexity of the viral quasispecies enables the virus population to spread systemically, perhaps through the complementing functions of different subpopulations, to successfully access the central nervous system. Taken together our data support a central concept of quasispecies theory, namely that successful colonization of the ecosystem, i.e. an infected animal, occurs by cooperation of different virus variants, which occupy distinct regions of the population sequence distribution 12. It is tempting to speculate that this type of positive cooperation also occurs during co-infection of a host with different viruses, which may have profound consequences for the pathogenic outcome of an infection.

Methods

For detailed methods, refer to online supplementary information.

Cells and viruses

Tissue culture experiments were performed in HeLa cells (ATCC CCL 2.2). Wildtype poliovirus type 1 Mahoney was used throughout this study. G64S virus derived from wildtype, contains a Serine in place of Glycine at position 64 of the viral RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Virus G64SSac contains a silent Sac I restriction site.

Guanidine hydrochloride resistance (Guar) assays

The evolution of the viral quasispecies was monitored by the spontaneous emergence of guar mutants in each virus population, as previously described 13.

Artificial expansion of G64S quasispecies by treatment with chemical mutagens

HeLa cells (107) were infected with 107 PFU of G64S virus in the presence of 400 μM ribavirin and 125 μg/ml of 5-fluorouracil. Mutagenized virus was harvested at total cytopathic effect and a second round of mutagenesis was performed using the same conditions. Following a drop in titers of at least 2 log, indicating that more than 99% of the genomes had been mutagenized, the population was allowed to recover to normal titers by passaging twice on fresh HeLa cell monolayers in absence of mutagen.

Genomic sequencing for mutational frequency

Using standard plaque assay, 24 virus isolates from the G64S or wildtype populations were isolated, amplified on HeLa cells and viral RNA was extracted and purified for RT-PCR. Direct sequencing was performed on PCR products spanning the 5’ non-coding and capsid protein coding region (nt 480-3300). Additionally, the G64S mutation was confirmed by sequencing to ensure that no reversion to wildtype had taken place. For the G64SeQS population, the entire 3CD sequence, including the 3D viral polymerase, was also sequenced to ensure no additional mutations had taken place.

Infection of susceptible mice

To determine the 50% lethal dose (LD50), 8 week old cPVR transgenic mice expressing the poliovirus receptor were inoculated intramuscularly with serial dilutions (20 mice/dilution) of wildtype, G64S or G64SeQS virus. Mice were monitored daily for symptoms leading to total paralysis. LD50 values were determined using the Reed and Muench method. For tissue tropism experiments, mice were inoculated intravenously with 107 or 108 pfu of wildtype, G64S or G64SeQS virus. Each day following infection, 5 mice from each group were euthanized and tissues were collected, homogenized and titered for virus on HeLa cells by standard plaque assay. To generate virus stocks of brain passaged virus, brain homogenates from each group (WT or G64SeQS mice infected i.v., or G64S mice infected i.m.) were pooled and virus contained therein was amplified once on HeLa cells to reach yields required for reinoculation experiments. For co-infection experiments, mice were infected intravenously with mixtures of wildtype or G64SeQS and G64SSac viruses. Tissues were collected on day 4. Virus present in tissues was first amplified on HeLa cells, and the amplified viral RNA was used for RT-PCR. The PCR products, spanning the capsid region, were digested with Sac I and analysed on agarose gel electrophoresis to examine whether wiltype or G64SeQS virus (1 band, approx. 3 kb) or G64SSac virus (2 bands, approx. 1.55 and 1.45 kb) were present.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Judith Frydman, Don Ganem, Alan Frankel, and members of the Andino lab for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants NIH-NIAID AI40085 to R.A, a pre-doctoral NIH fellowship to JKS, and AI054776 to CEC.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Nature’s website (http://www.nature.com).

Competing interest statement. The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Holland J, et al. Rapid evolution of RNA genomes. Science. 1982;215:1577–85. doi: 10.1126/science.7041255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland JJ, De La Torre JC, Steinhauer DA. RNA virus populations as quasispecies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;176:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77011-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingo E, Holland JJ. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:151–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eigen M. Viral quasispecies. Sci Am. 1993;269:42–9. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0793-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingo, E., Holland, J. & Ahlquist, P. RNA genetics (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla, 1988).

- 6.Domingo, E. & Holland, J. Mutations and rapid evolution of RNA viruses (ed. S., M. S.) (Raven Press, New York, 1994).

- 7.Domingo E. Viruses at the Edge of Adaptation. Virology. 2000;270:251. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domingo E, Sabo D, Taniguchi T, Weissmann C. Nucleotide sequence heterogeneity of an RNA phage population. Cell. 1978;13:735–44. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffin JM. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domingo E, et al. Basic concepts in RNA virus evolution. Faseb J. 1996;10:859–64. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.8.8666162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eigen, M. & Biebricher, C. Sequence space and quaispecies distribution (eds. Domingo, E., Holland, J. & Ahlquist, P.) (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FLa, 1988).

- 12.Biebricher CK, Eigen M. The error threshold. Virus Res. 2005;107:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crotty S, et al. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside ribavirin is an RNA virus mutagen. Nat Med. 2000;6:1375–9. doi: 10.1038/82191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crotty S, Cameron CE, Andino R. RNA virus error catastrophe: direct molecular test by using ribavirin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6895–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111085598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson AA, Peersen OB. Structural basis for proteolysis-dependent activation of the poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Embo J. 2004;23:3462–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfeiffer JK, Kirkegaard K. A single mutation in poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase confers resistance to mutagenic nucleotide analogs via increased fidelity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7289–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232294100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baltera RF, Jr, Tershak DR. Guanidine-resistant mutants of poliovirus have distinct mutations in peptide 2C. J Virol. 1989;63:4441–4. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4441-4444.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pincus SE, Diamond DC, Emini EA, Wimmer E. Guanidine-selected mutants of poliovirus: mapping of point mutations to polypeptide 2C. J Virol. 1986;57:638–46. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.638-646.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold, J. J., Vignuzzi, M., Stone, J. K., Andino, R. & Cameron, C. E. Remote-site control of an active-site fidelity checkpoint in a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Gohara DW, Arnold JJ, Cameron CE. Poliovirus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (3D(pol)): Kinetic, Thermodynamic, and Structural Analysis of Ribonucleotide Selection. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5149–58. doi: 10.1021/bi035429s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmenberg, A. C. & Sgro, J. Y. Alignment of enterovirus polyproteins. http://www.virology.wisc.edu/acp/Aligns/aligns/entero.p123 (1994).

- 22.Ren R, Racaniello VR. Poliovirus spreads from muscle to the central nervous system by neural pathways. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:747–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JP, Daifuku R, Loeb LA. Viral error catastrophe by mutagenic nucleosides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:183–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pariente N, Sierra S, Lowenstein PR, Domingo E. Efficient virus extinction by combinations of a mutagen and antiviral inhibitors. J Virol. 2001;75:9723–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9723-9730.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pariente N, Airaksinen A, Domingo E. Mutagenesis versus inhibition in the efficiency of extinction of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J Virol. 2003;77:7131–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7131-7138.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.