Abstract

To identify the potential functions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) in skin development, transgenic mice were generated to target constitutively activated PPARα (VP16PPARα) to the stratified epithelia by use of the keratin K5 promoter. In addition to marked alterations in epidermal development, the transgenic mice had a severe defect in lactation during pregnancy resulting in 100% pup mortality. In this study, the alteration of mammary gland development in these transgenic mice was investigated. The results showed that expression of the VP16PPARα transgene during pregnancy resulted in impaired development of lobuloalveoli, which is associated with reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis of mammary epithelia. Mammary epithelia from transgenic mice also showed a significant reduction in the expression of β-catenin and a down-regulation of one of its target genes, cyclin D1, which is thought to be required for lobuloalveolar development. Furthermore, upon PPARα ligand treatment, similar effects on lobuloalveolar development were observed in wild-type mice, but not in PPARα-null mice. These findings suggest that PPARα activation has a marked influence in mammary lobuloalveolar development.

Keywords: VP16PPARα, mammary gland, lobuloalveoli, lactation, cyclin D1, β-catenin

Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily and function as classic ligand-responsive transcription factors that participate in many physiological processes (1). Three isoforms of PPARs (α, β/δ, and γ) were identified in frogs, mice, non-human primates, and humans (2-4). Upon binding to their ligands, PPARs undergo conformational changes that allow co-repressor release and co-activator recruitment, heterodimerization with RXR and selectively binding to a degenerate direct repeat hexameric nucleotide sequence separated by one base (direct repeat 1, DR1), also called peroxisome proliferator responsive element (PPRE) (2). PPREs are found in the promoter regions of several genes that are mainly involved in lipid storage, transport and metabolism (5-7).

PPARα is expressed in many tissues requiring, under certain physiological conditions, fatty acids as an energy source such as liver, kidney and heart (8, 9). However, PPARα has also been identified in rodent and human keratinocytes (8, 10, 11) and a number of PPARα ligands were shown to alter epidermal homeostasis (12-15). To further investigate the role of PPARα in epithelial tissues, a transgenic mouse line was generated in which a constitutively-activated PPARα is expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis under control of the bovine keratin K5 promoter and the tetracycline regulatory system (16). In addition to the marked alterations in epidermal development, the transgenic mice had a severe defect in lactation during pregnancy and resulting in newborn mortality which is consistant with keratin 5 promoter expression in the myoepithelium of the mammary gland (17-19). However, the information on the involvement of PPARα in mammary development is limited. All three PPARs are expressed in both stromal adipocytes and epithelial cells in rodent mammary tissues (20), and the levels of PPARα and PPARγ mRNAs decrease during pregnancy and lactation while the PPARβ remains relatively unchanged (20). In rodent mammary tumor models, PPAR ligands were reported to reduce tumor incidence and progression (21-24). However, there is no evidence that PPARα activation results in impaired mammary development and lactation. Targeted disruption of PPARα has revealed no reported phenotype associated with mammary gland development (25) suggesting that PPARα is not required for mammalian development in the mouse model; however this does not exclude a role for activated receptor.

The current study revealed that activation of PPARα during pregnancy impairs mammary gland development and results in a defect of lactation and pups mortality. To this end, the transgenic mice with constitutively activated PPARα under the control of K5 promoter were used to assess mammary gland development at various stages of pregnancy (16). The consequences of exposure of wild-type or PPARα-null mice to PPARα ligand during pregnancy were also examined. The results revealed severe defects in lobuloalveolar development upon activation of PPARα during pregnancy and suggest that lactation and neonatal survival are adversely affected by activation of PPARα.

Experimental animals

Mice targeting constitutively activated PPARα in epidermis and other stratified epithelia, under the control of the keratin K5 promoter were recently generated (16). Briefly, the potent viral transcriptional activator VP16 was fused to the mouse PPARα cDNA to create a transcription factor that constitutively activates PPARα target genes in the absence of ligand. The single transgenic mice were generated with the VP16PPARα cDNA driven by the tetracycline response element (TREVP16PPARα) (Fig 1A). Double transgenic (designated Tg) mice were generated by breeding TREVP16PPARα mice with transgenic mice (K5-tTA) expressing tTA under the control of keratin 5 promoter (26) to reconstitute the tetracycline responsive regulatory system (27, 28). TREVP16PPARα mice and K5-tTA mice behaved similar to wild-type (Wt) mice throughout the study. Therefore, mice with these three genotypes were grouped together as control littermates unless otherwise specified.

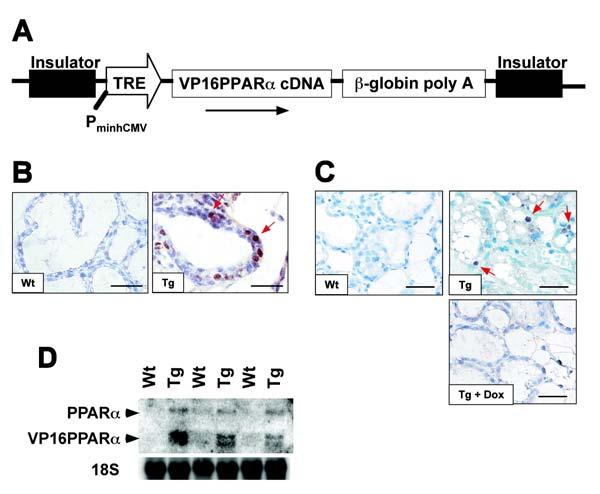

Figure 1.

Generation of transgenic mice and analysis of transgene expression. (A) Schematic representation of the 7-kb construct used for generating tetracycline response element-VP16PPARα (TREVP16PPARα) transgenic mice. PminhCMV, minimal human cytomegalovirus promoter. (B) VP16 immunostaining in mammary gland. Sections of Wt glands and Tg glands in the absence of dox were stained with anti-VP16 antibody. (C) PPARα immunostaining in mammary gland. Sections of Wt glands and Tg glands in the absence or in the presence of dox were stained with anti-PPARα antibody. In both B and C, positive cells were visualized with DAB (brown, shown by red arrows). Nuclei were counter-stained with hematoxylin (blue). Bars: 125 μm. (D) Northern blot analysis of RNA from day 1 of parturition. The expression of the VP16PPARα transgene was observed only in Tg animals in the absence of dox.

The mice were maintained under a standard 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with water and chow provided ad libitum. Handling was in accordance with animal study protocols approved by the National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee. Females were housed with males and checked daily for presence of vaginal plugs. The day that the vaginal plug was found was designated as day 0.5 of pregnancy. Pregnant mice were then individually housed for the remainder of the study. Virgin mice were not housed with male mice. To characterize the effect of PPARα ligand on mammary gland development through pregnancy, wild-type and PPARα-null mice were given pelleted mouse chow containing 0.1% (w/w) Wy-14,643 (Bioserv, Frenchton, NJ) from day 0.5, 7.5, 12.5, or 15.5 during pregnancy and killed on parturition day 1. Some double transgenic mice were administered doxycycline (dox; 200 mg/kg; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) in the diet to regulate expression of the transgene VP16PPARα

To assess cell proliferation, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.25 mg 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)/g body weight 2 hours prior to killing by overexposure to carbon dioxide. The mammary glands were removed. Tissues not used for histology were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further analysis.

Materials and Methods

Hormone analysis

Blood was collected from mouse suborbital veins and separated by a serum separator tube (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The concentrations of serum estradiol and progesterone were determined using commercial ELISA kits (Alpha Diagnostic, San Antonio, TX).

Mammary gland whole mounts

Preparation of mammary glands was previously described (http://mammary.nih.gov/methodcd/methodcd.html). Briefly, the fourth abdominal mammary glands were collected on the indicated day of pregnancy. One gland from each animal was spread onto a glass slide under weight, fixed in Carnoy’s fixative solution, stained with carmine alum, and permanently mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining and immunohistochemistry

Another gland from each mouse was fixed in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μM) were mounted on glass slides (Superfrost/plus, A. Daigger & Company, Inc., IL), deparaffinized by xylene and dehydrated by graded ethanol, and processed for histology. For histology, tissues were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin.

Immunostaining for mouse PPARα, PCNA (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), VP16 tag (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and cyclin D1 (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA) were performed using polyclonal antibodies. Each primary antibody was detected by ABC-kit (Vector Laboratory Inc., Burlingame, CA). Immunostaining for BrdU (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) and β-catenin (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) was performed using monoclonal antibody, which was labeled with biotin by ARK kit (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) prior to application to the tissues. In brief, sections were washed in PBS and were incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in 100% methanol for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 100°C for 10 min. After washing in PBS, the sections were blocked in PBS containing 5% skim milk at room temperature for 30 min. The sections were then rinsed and incubated sequentially in primary antibody (diluted 1: 100 in PBS containing 1% BSA) for 2 h at room temperature, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (diluted 1: 50 in PBS containing 1% BSA) for 30 min (when polyclonal antibody was used as the primary antibody), avidin-biotinylated peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA) in PBS for 30 min. The bound antibody was visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a peroxidase substrate. Sections were rinsed in water, counterstained with Hematoxylin (Sigma), dehydrated, and mounted in permanent mounting medium.

Proliferation and Apoptosis assays

Proliferation assays were performed as described previously by monitoring the incorporation of BrdU injected 2 hrs before killing (29). Proliferating cells were quantitated as number of brown color (i.e. BrdU incorporated) cells out of the total hematoxylin-stained cells (blue nuclei).

Apoptosis in mammary glands was analyzed by using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) as previously described (30). For both proliferation and apoptosis assays, only luminal epithelial cells were included in these counts. At least 2000 cells from three animals were counted for each group at each time-point.

Quantitative real-time PCR and northern blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated by mechanical disruption of mammary tissue in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of RNA was determined by spectrophotometry. cDNA was synthesized from an equivalent amount of total RNA from each sample using Superscript first strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primers were designed for real-time PCR using the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequence and Genbank accession number for the forward and reverse primers used to quantify mRNA were: β-casein (NM_009972) Forward: 5′-GGATGTGCTCCAGGCTAAAGTTC-3′ and Reverse: 5′-TGTTTTGTGGGACGGGATTG-3′, whey acidic protein (WAP) (NM_011709) Forward: 5′-CCATTGAGGGCACAGAGTGTATC-3′ and Reverse: 5′-TTGACAGGAGTTTTGCGGGTC-3′. Real-time reactions were carried out using SYBR Green PCR master mix (AB Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) using the ABI PRISM 7900 HT sequence detection system (AB Applied Biosystems). The following conditions were used for PCR: 95°C for 15 sec, 94°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, in 45 cycles. Relative expression levels of mRNA were normalized to GAPDH and analyzed for statistical significance with a student t-test.

Northern blot analysis was carried out as described previously (31). Briefly, 10 μg of total RNA was electrophoresed on a 1.0% agarose gel containing 0.22 M formaldehyde, transferred to a nylon membrane, and cross-linked by exposure to ultraviolet light. The previously described cDNA probes (PPARα and cyclin D1) were used for northern blotting and 18S as a loading control (32). Membranes were hybridized in ULTRAhyb buffer (Ambion, Austin, TX) with random primer 32P-labeled cDNA probes following the manufacturer’s protocol, and washed with salt/detergent solution using standard procedures.

Statistical Analysis

All of the values are expressed as the mean ± SD. All of the data were analyzed by paired or unpaired Student’s t test for significant differences between the mean values of each group. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Expression and regulation of the VP16PPARα transgene in mammary gland

The transgene used to express constitutively-activated PPARα in the epidermis and other stratified epithelia, under control of the keratin K5 promoter is shown in Fig. 1A (16). Immunohistochemical analysis of mammary glands revealed that in contrast to the absence of VP16PPARα proteins in Wt mammary glands, VP16PPARα, as detected by use of a VP16 antibody that detects the fusion protein, was expressed in the basal epithelial cells and not in the luminal epithelial cells of Tg mice in the absence of dox (Fig. 1B). However, the expression of PPARα revealed that in contrast to no detectable PPARα in Wt mice, PPARα proteins were detected in the luminal epithelial cells of Tg mice in the absence of dox, suggesting that endogenous PPARα may have been up-regulated in these cells (Fig. 1C). The PPARα induced in mammary epithelial cells was repressed in the presence of dox (Fig. 1C) which suppresses expression of the VP16PPARα transgene as shown by northern blot analysis of mammary glands, in which the VP16PPARα transgene was only expressed in Tg mice in the absence of dox (Fig. 1D). Northern blot analysis also revealed that mammary glands in Wt dams expressed very low levels PPARα. It should also be noted that the expression of endogenous PPARα is highly induced by VP16PPARα (Fig. 1D), a result that is consistent with expression of VP16PPARα as revealed by immunohistochemistry.

Impaired lobuloalveolar development in Tg mammary glands

In a previous study, impaired lactation was observed in Tg dams. All pups produced by Tg dams could not obtain adequate milk and thus died within 2 days of birth. Wt pups cross-fostered with Tg dams exhibited the same extent of lethality. However, as expected, when dams received dox from the diet, the impaired phenotype was rescued, demonstrating that expression of the VP16PPARα transgene led to a defect in the lactation (16).

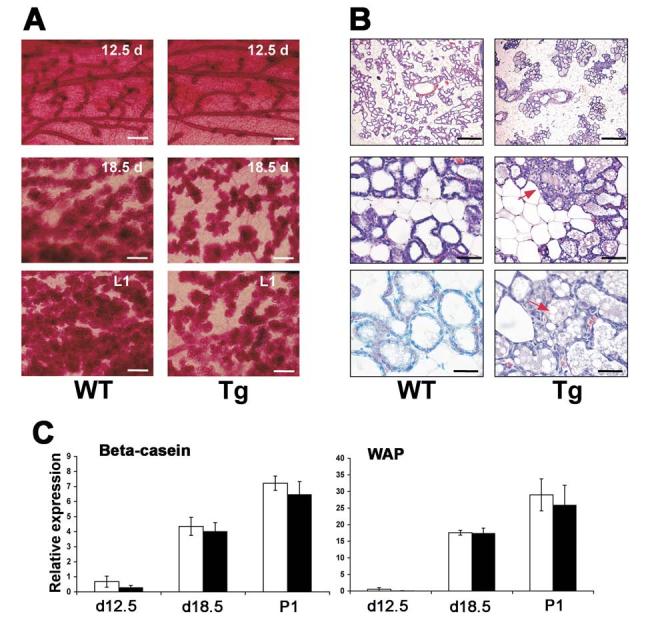

Whole-mount analysis of mammary glands was used to examine the development of mammary gland during pregnancy. At day 12.5 during pregnancy, the Tg dams completed normal ductal development with the usual ductal structure and branching compared to Wt dams (Fig. 2A). In late-pregnancy (18.5 d), the density of alveoli in Tg dams was lower than in Wt controls and was most pronounced in the day just after parturition (L1) (Fig. 2A). As expected, this phenotypic defect could be reversed after treatment with dox through the diet (data not shown), indicating that it was caused by expression of VP16PPARα during pregnancy. Therefore, the expression of VP16PPARα in mammary glands appeared to inhibit mammary lobuloalveolar development.

Figure 2.

Impaired lobuloalveolar development in the transgenic mammary glands during pregnancy. (A) Morphological observation by whole mount. Wt and Tg mammary glands in the absence of dox at different time during pregnancy from day 12.5 to day 1 of parturition (L1) were compared. Note although continued side branching, alveolar development in Tg glands was severely hypoplastic as compared with Wt controls. (B) Histological analyses by H&E staining. Wt and Tg glands in the absence of dox at L1 were compared. Top panels are low magnification of glands. Note there is a scarce distribution of alveoli in Tg glands. Middle panels are medium magnification of glands. Note some alveolar structure was disrupted in Tg glands (representative shown by red arrow). Bottom panels are high magnification of glands. Note there are accumulated lipid droplets in Tg glands (representative shown by red arrow). Bars: (A) 1.25 mm; (B) top: 1.25 mm; middle: 250 μm; bottom: 125 μm. (C) Relative expression of milk protein genes. Expression of β-casein and WAP mRNAs were analyzed using total RNA extracts from Wt and Tg glands in the absence of dox at L1 by quantitative real-time PCR.

H&E staining confirmed the failure of proper lobuloalveolar development in Tg mammary glands. At L1, the stroma of Wt dams is typically packed with well-extended alveolar lobules (Fig. 2B). However, the Tg dams at L1 showed an unevenly spaced and condensed distribution of the lobuloalveoli compared to Wt dams. The numbers of alveoli in Tg dams were also lower than Wt controls. High magnification of mammary glands showed that some of the typical luminal structure was disrupted in Tg dams. In addition, more remnants of lipid droplets are noted in the alveoli of Tg dams as compared with Wt dams. The accumulation of lipid in Tg alveoli was also observed before parturition, e.g., day 18.5 (data not shown), indicating that this is not due to residual milk no removed by the pups. The expression of milk protein genes increased dramatically during pregnancy. At day 12.5 during pregnancy, β-casein mRNA is clearly expressed, while very weak expression of WAP mRNA was observed at this stage. In late-pregnancy (18.5 d) and during lactation, both β-casein and WAP mRNAs were highly expressed. However, the expression of β-casein and WAP mRNAs was not significantly changed in Tg dams compared to Wt controls at these stages (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the defect in lactation may not be due to lack of milk production. As expected, both estradiol and progesterone serum levels were not changed in Tg dams (data not shown), which rules out hormone-deficiency as a cause of the defect in lobuloalveolar development. Together with the specificity of the K5 promoter (26), these data indicated that the defect seen in Tg mice was intrinsic to the mammary epithelium.

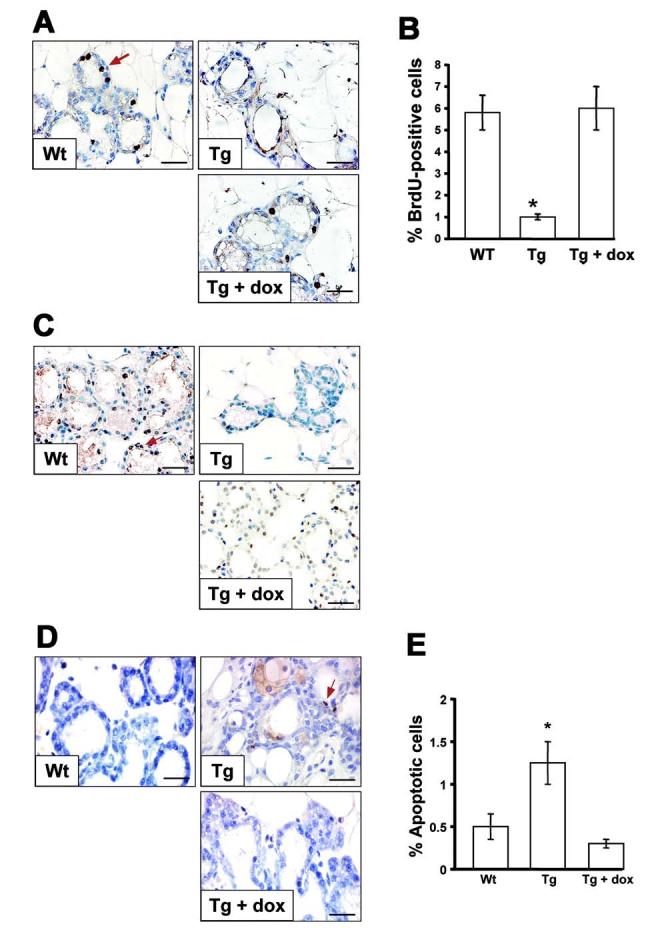

Reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis in Tg mice

To determine whether the defect in mammary lobuloalveoli development was the result of reduced cell proliferation or increased cell death, BrdU incorporation and TUNEL assays were performed. The incorporation of BrdU into DNA was detected by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3A) and the proliferation index was calculated as a percentage of BrdU-positive alveolar cells per total epithelial cells (Fig. 3B). The results showed that the proliferation rate of Tg mammary epithelium in the absence of dox was dramatically decreased compared to Wt or Tg epithelial cells in the presence of dox. Similar results were obtained by detection of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a marker for S phase cells. The number of PCNA-positive cells in the Tg mammary epithelium was also dramatically lower than in the Wt or Tg cells in the presence of dox (Fig. 3C). These results strongly suggest that PPARα signaling plays an important role in proliferation of the lobuloalveolar epithelium in response to pregnancy signals. In addition, the apoptotic cells were increased in mammary epithelial cells from Tg dams in the absence of dox compared to Wt or Tg dams in the presence of dox as revealed by TUNEL assay (Fig. 3D and E), that may also contribute to the observed hypoplastic development of lobuloalveoli.

Figure 3.

Impaired epithelial proliferation in transgenic mammary glands. (A) BrdU incorporation and detection. BrdU was administrated to Wt and Tg mice in the absence or in the presence of dox at L1 and the mammary glands were removed 2 hr later. BrdU incorporated into mammary glands was detected by immunohistochemistry. Positive cells were visualized with DAB (brown, representative shown by red arrow). Nuclei were counter-stained with hematoxylin (blue). (B) BrdU labeling indices. 300 - 400 epithelial cell nuclei were examined per sections of Wt and Tg glands. The values represent the average fraction of BrdU-positive epithelial cells per total number of epithelial cells of three different mice, p < 0.001. Note Tg glands without dox had decreased numbers of BrdU positive cells compared with Wt controls or Tg in the presence of dox. (C) PCNA detection. PCNA was detected in mammary glands of Wt and Tg glands in the absence or in the presence of dox at L1. Positive cells were visualized with DAB (brown, representative shown by red arrow). Nuclei were counter-stained with hematoxylin (blue). Note Tg glands without dox had decreased numbers of PCNA positive cells compared with Wt or Tg with dox glands. (D) TUNEL assay. Paraffin sections of mammary glands at L1 from Wt and Tg glands in the absence or in the presence of dox were subjected to TUNEL analysis. Positive cells were visualized with ABC (brown, representative shown by red arrow). Nuclei were counter-stained with a hematoxylin (blue). (E) Percentage of apoptotic cells in mammary epithelial cells. 300 - 400 epithelial cell nuclei were examined per sections. The values represent the average fraction of TUNEL positive epithelial cells per total number of epithelial cells of three different mice, p < 0.001. Note Tg glands without dox displayed increased numbers of apoptotic cells compared with Wt or Tg with dox glands. Bars: 125μm.

Decreased expression of cyclin D1 and β-catenin in Tg mice

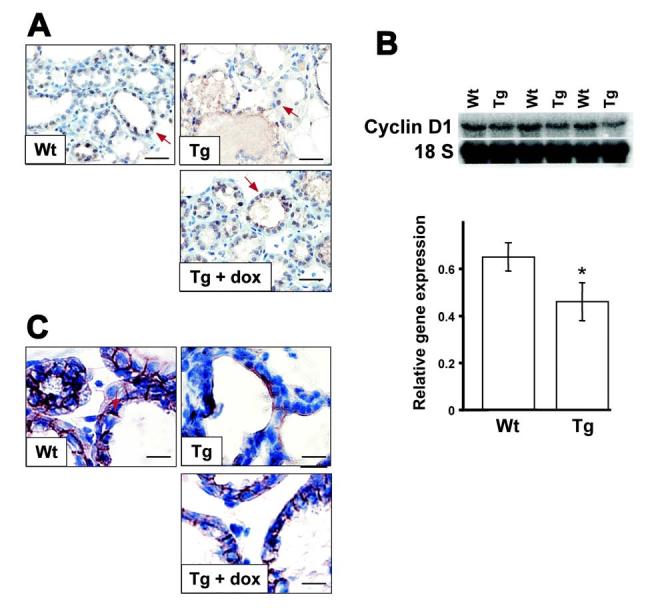

The reduced proliferation and, in particular, the reduced PCNA expression in transgenic mammary epithelial cells suggested that expression of cell cycle regulators were altered upon expression of the VP16PPARα transgene. Cyclin D1 is a critical component of the core cell cycle machinery. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that, in the absence of dox, only 15.6% of Tg mammary epithelial cells were cyclin D1 positive versus 85.5% of Wt cells or 80.2% of Tg in the presence of dox (Fig. 4A). However, by northern blotting, expression of cyclin D1 gene from whole mammary gland at L1 was only slightly decreased upon expression of the VP16PPARα transgene compared to Wt dams at L1 (Fig. 4B). This suggests that changes in cyclin D1 may be largely confined to epithelial cells, but not other cells that are constituents of the mammary gland. These results suggest that the proliferation defect in Tg mammary epithelium may be due, at least in part, to the reduced cyclin D1 expression in mammary epithelial cells.

Figure 4.

Defect in the β-catenin-cyclin D1 pathway in transgenic mouse mammary glands. (A) immunohistochemistry of cyclin D1. Cyclin D1 was detected in Wt and Tg mammary glands in the absence or in the presence of dox at L1 by immunohistochemistry. Positive cells were visualized with DAB (brown, representative shown by red arrow). Nuclei were counter-stained with hematoxylin (blue). Note Tg glands without dox displayed reduced levels of cyclin D1 expression compared with Wt glands or Tg with dox. (B) Northern blot analysis of cyclin D1 expression in Wt and Tg whole mammary glands in the absence of dox. Average relative expression levels are indicated below with arbitrary value. (C) immunohistochemistry of β-catenin. β-catenin was detected in Wt and Tg mammary glands in the absence or in the presence of dox at L1 by immunohistochemistry. Positive cells were visualized with DAB (brown, representative shown by red arrow). Nuclei were counter-stained with hematoxylin (blue). Note Tg glands without dox showed reduced levels of β-catenin compared with high levels of cytoplasmic β-catenin expression in Wt or Tg with dox glands. Bars: (A) 125μm; (C) 250μm.

As cyclin D1 has been identified as a bona fide target gene of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, the possible inhibitory effects of VP16PPARα in Wnt signaling was examined. Even though high levels of β-catenin in the membrane of mammary epithelia at L1 were consistently found in Wt or Tg glands in the presence of dox, the Tg mice in the absence of dox showed relatively lower levels of β-catenin at L1 (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the inhibitory effects of VP16PPARα on alveolar development may be through the Wnt/β-catenin - cyclin D1 pathway.

Suppression of mammary lobuloalveolar development by the PPARα ligand, Wy-14,643

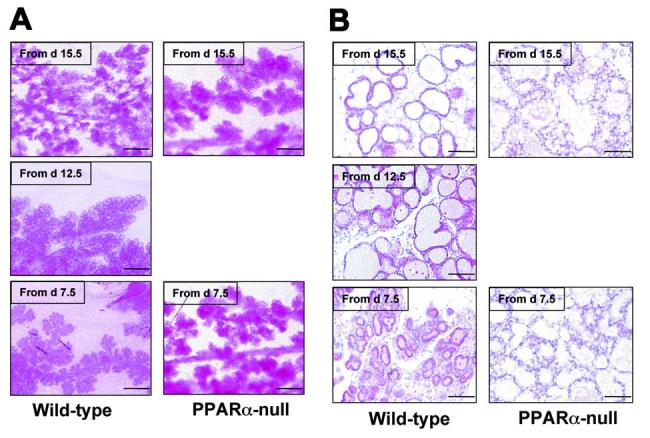

To determine whether the impaired lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy by expression of the VP16PPARα transgene can be reproduced by PPARα ligands, both wild-type and PPARα-null female impregnated mice were treated with PPARα ligand Wy-14,643 from different time points during pregnancy and killed on L1. Treatment of wild-type mice from day 0.5 during pregnancy resulted in embryo lethality (n = 10) as revealed by no embryos at later stages of pregnancy. However, treatment of wild-type mice from day 7.5 yielded no embryonic lethality. As expected, profound suppression of mammary lobuloalveolar development was observed. Specifically, the density and the size of alveoli in Wy-14,643 treated dams were highly decreased when compared to untreated controls (Fig. 5A and 2A). This effect was gradually weaker by shorter treatment times, e.g., from day 12.5 or 15.5 during pregnancy (Fig. 5A). In contrast, treatment of PPARα-null mice with Wy-14,643 from day 7.5 during pregnancy did not cause significant morphological changes of the mammary glands (Fig. 5A). H&E staining confirmed this conclusion. Thus, in Wt mice, treatment with Wy-14,643 from day 7.5 resulted in smaller alveoli and this effect was gradually weaker by shorter treatment times whereas PPARα-null mice did not demonstrate different morphology from untreated wild-type mice (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, increased lipid droplets were observed in Wy-14,643 treated PPARα-null mice (Fig. 5B). These data further establish that activation of PPARα results in impaired lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy.

Figure 5.

Impaired lobuloalveolar development in wild-type mouse mammary glands upon Wy-14,643 treatment during pregnancy. Pregnant Wt and PPARα-null female mice were treated with Wy-14,643 from indicated time, and the mammary glands were removed at L1. (A) Morphological observation by whole mount. Note lobuloalveolar development was inhibited by Wy-14,643 in wild-type mice in a time dependent manner, but not in PPARα-null animals. (B) Histological analyses by H&E staining. Note the small alveoli observed in Wt mice upon Wy-14,643 treatment from day 7.5, but not in PPARα-null mice. PPARα-null mice have accumulated lipid droplets in the lumen. Bars: 125μm.

Discussion

Functional differentiation of the mammary gland is a crucial step in the reproductive cycle of mammals. Distinct steps of mammary epithelium differentiation and proliferation take place during puberty, pregnancy and lactation (33). PPARα is not necessary for mammary gland development as PPARα-null mice have normal mammary gland development during pregnancy and exhibit normal nursing behavior, however, activation PPARα during pregnancy resulted in impaired lobuloalveolar development that probably contributed to the severe defect in lactation and pup death observed in this transgenic mouse line (16). Similar effects on lobuloalveolar development were also found in wild-type mouse mammary glands upon PPARα ligand treatment, but not in mammary glands from PPARα-null mice. There was also increased pup mortality in Wy-14,643-treated wild-type mice that could be due to the alterations in mammary gland development, modified suckling behavior or subtle changes hormonal levels as a result of drug treatment. As the physiological expression of PPARα is dramatically decreased in mammary gland during pregnancy and lactation (20), it is not surprising that activation of PPARα alters the development of mammary glands during these reproductive changes.

Expression of the VP16PPARα transgene was found in myoepithelial cells, the target site of the keratin 5 promoter consistent with previous studies using same promoter (19), while endogenous PPARα was induced in the luminal epithelial cells of the transgenic mice. These results suggest that interactions may exist between the two mammary epithelial cell layers, and suggest the presence of a paracrine signal. In wild-type mammary glands, PPARα expression is not detected by immunohistochemistry either with and without Wy-14,643 treatment probably due to its low level expression and the lack of sufficient sensitivity of the technique in detecting low abundance nuclear protsins. However, by use of quantitative real-time PCR PPARα mRNA was readily detected in wild-type mice; these levels were only minimally increased by Wy-14,643 treatment (data not shown). Wy-14,643 treatment presented the same mammary gland phenotypes as found in the VP16PPARα transgenic mice, suggesting that the level of PPARα expression does not necessarily correlate with the activation of PPARα target genes. A paracrine signal from myoepithelial cells where the VP16PPARα transgene is expressed, may affect the luminal epithelial cells of transgenic mice, resulting in enhanced expression and activation of the endogenous PPARα. Indeed, auto-regulation of human PPARα gene by PPARα was reported (34). The VP16PPARα may induce myoepithelial cells to produce a paracrine factor that interferes with alveolar development, or suppresses the production of paracrine factors such as RANKL, Wnt4 and IGF-2, which have been shown to be important for alveolar development (35-37). In this regard, it is interesting to note that RANKL, RANK or C/EBPβ act in a signaling pathway that also involves cyclin D1 (35, 38), and mice null for these genes failed to develop alveolar structures (35, 39). In this context, it was reported that activating PPARα signaling inhibits C/EBPβ or NFκB signaling (40, 41). Changes in these pathways may affect PPARα signaling. Similar to the current observation in mammary glands, induction of endogenous PPARα in VP16PPARα transgenic mice was also previously observed in skin and tongue (16). This suggests that the same mechanism may exist in stratified epithelial cells. The precise mechanism for the effect of the expression of VP16PPARα in myoepithelial cells on the expression of endogenous PPARα in luminal epithelial cells remains to be determined.

It is well known that PPARα is involved in the control of lipid transport and metabolism. In mouse skin, activation of PPARα by the VP16PPARα transgene or PPARα ligand resulted in up-regulation of adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP or adipophilin in human) and fasting-induced adipose factor (FIAF), which play important roles in the uptake and accumulation of lipids (16, 42). Up-regulation of ADRP is thought be responsible for the formation of lipid droplets in many cell types. The accumulated lipid droplets observed in transgenic mammary lumen suggests that the same mechanism might exist in this tissue. The increased lipid droplets were also observed in PPARα-null dams in the present study. This may be due to alterations in lipoprotein metabolism as previously observed in PPARα-null mice (43). However, PPARα-null dams exhibited normal lobuloalveolar development. The accumulated lipid droplets in mammary epithelial cells were also observed in mice with constitutive activation of Akt in mammary glands, while these dams exhibit normal lobuloalveolar development (44). Thus, the elevated lipid droplets in the VP16PPARα transgenic mice may not influence lobuloalveolar development. However, the lipid droplets in transgenic mice may influence nursing since decreased nursing was observed in transgenic mice with constitutive activation of Akt in mammary glands due to increased lipid content in the milk (39). Previous cross-fostering experiments excluded suckling defects by pups (16). Thus, it is possible that the increase in milk viscosity by changes in milk composition may also result in a defect in milk ejection in the VP16PPARα transgenic mice. Further studies are needed to determine this possibility.

The marked decrease in transgenic mammary epithelial cell proliferation during pregnancy might directly cause the observed phenotypes in transgenic mammary gland. The decreased proliferation of mammary epithelial cells is consistent with the effects of VP16PPARα on keratinocytes, which also caused an attenuation of cell proliferation (16). In addition, the increased apoptosis in these cells may also contribute to the reduced alveoli in transgenic dams.

The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the Wnt signaling pathway, which is activated by β-catenin and TCF/LEF (45, 46). In the case of adipocytes that express high levels of PPARγ and β-catenin, adipogenesis is dependent on the balance between PPARγ and β-catenin signaling (47). β-catenin functions as a promoter of preadipocyte growth and proliferation through cyclin D1, and also functions as a potent inhibitor of adipogenesis (48). Recently, the cross-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf ligands and associated transcription factors with members of the nuclear receptor family has emerged as a clinically and developmentally important area of endocrine cell biology (49). Indeed, a dramatic reduction in expression of cyclin D1 and β-catenin was observed in mammary epithelial cells of transgenic dams. However, to our knowledge, no PPARα target genes that directly regulate the cell cycle have been identified, although ligand activation of PPARα in liver was reported to increase the expression of cyclin D1 (32). In this context, a dramatic reduction of cyclin D1 was also observed previously in keratinocytes from VP16PPARα transgenic mice (16), suggesting that the same mechanism may exist. Interestingly, a mouse model with a targeted mutation in cyclin D1 or with silenced β-catenin signaling also exhibit a very similar defect in mammary gland development as the VP16PPARα model, including no effect on ductal side branching, but specific inhibition of alveolar development with compromised lactation resulting in pup death (50-53). This suggests the effects of activated PPARα on mammary alveolar development may be through interference with the β-catenin-cyclin D1 pathway. Thus, a mechanistically reciprocal interplay of inhibitory signals may occur between PPARα and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. However, how PPARα signaling regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mammary epithelium requires further studies.

While PPARα ligands induce pleiotropic responses in rodents, results from VP16PPARα transgenic mice indicate that the impaired alveoli development is due to activation of PPARα in mammary glands. In addition, PPARα ligand treatment of dams also caused embryonic lethality at an early stage of pregnancy. To our knowledge, the effect of PPARα ligands exposure on lactation in humans has not been studied. Thus, epidemiological data on the effects of PPARα ligands on breast development and function may be warranted in view of the current study. On the other hand, the development of mammary gland is complex and unique. Determining the contribution of PPARα signaling to mammary epithelial cell proliferation and its influence on Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cell cycle regulation may also be of value in understanding mammary gland biology.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

- BrdU

- 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor

- TRE

- tetracycline response element

- TUNEL

- TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling

- Wt

- wild-type.

Address correspondence to: Frank J. Gonzalez, Building 37, Room 3106B, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892. Phone: (301) 496-9067. Fax: (301) 496-8419. E-mail: fjgonz@helix.nih.gov

References

- 1.Willson TM, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, Henke BR. The PPARs: from orphan receptors to drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2000;43:527–550. doi: 10.1021/jm990554g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347:645–650. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreyer C, Krey G, Keller H, Givel F, Helftenbein G, Wahli W. Control of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway by a novel family of nuclear hormone receptors. Cell. 1992;68:879–887. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kliewer SA, Forman BM, Blumberg B, Ong ES, Borgmeyer U, Mangelsdorf DJ, Umesono K, Evans RM. Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7355–7359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. Retinoid X receptor interacts with nuclear receptors in retinoic acid, thyroid hormone and vitamin D3 signalling. Nature. 1992;355:446–449. doi: 10.1038/355446a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Noonan DJ, Heyman RA, Evans RM. Convergence of 9-cis retinoic acid and peroxisome proliferator signalling pathways through heterodimer formation of their receptors. Nature. 1992;358:771–774. doi: 10.1038/358771a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keller H, Dreyer C, Medin J, Mahfoudi A, Ozato K, Wahli W. Fatty acids and retinoids control lipid metabolism through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2160–2164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauca M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137:354–366. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escher P, Braissant O, Basu-Modak S, Michalik L, Wahli W, Desvergne B. Rat PPARs: quantitative analysis in adult rat tissues and regulation in fasting and refeeding. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4195–4202. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michalik L, Desvergne B, Dreyer C, Gavillet M, Laurini RN, Wahli W. PPAR expression and function during vertebrate development. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivier M, Safonova I, Lebrun P, Griffiths CE, Ailhaud G, Michel S. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor subtypes during the differentiation of human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:1116–1121. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanley K, Jiang Y, Crumrine D, Bass NM, Appel R, Elias PM, Williams ML, Feingold KR. Activators of the nuclear hormone receptors PPARalpha and FXR accelerate the development of the fetal epidermal permeability barrier. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:705–712. doi: 10.1172/JCI119583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanley K, Jiang Y, He SS, Friedman M, Elias PM, Bikle DD, Williams ML, Feingold KR. Keratinocyte differentiation is stimulated by activators of the nuclear hormone receptor PPARalpha. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:368–375. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanley K, Komuves LG, Bass NM, He SS, Jiang Y, Crumrine D, Appel R, Friedman M, Bettencourt J, Min K, Elias PM, Williams ML, Feingold KR. Fetal epidermal differentiation and barrier development In vivo is accelerated by nuclear hormone receptor activators. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:788–795. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komuves LG, Hanley K, Jiang Y, Elias PM, Williams ML, Feingold KR. Ligands and activators of nuclear hormone receptors regulate epidermal differentiation during fetal rat skin development. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:429–433. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Q, Yamada A, Kimura S, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ. Alterations in Skin and Stratified Epithelia by Constitutively Activated PPARalpha. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:374–385. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berton TR, Matsumoto T, Page A, Conti CJ, Deng CX, Jorcano JL, Johnson DG. Tumor formation in mice with conditional inactivation of Brca1 in epithelial tissues. Oncogene. 2003;22:5415–5426. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teuliere J, Faraldo MM, Deugnier MA, Shtutman M, Ben-Ze’ev A, Thiery JP, Glukhova MA. Targeted activation of beta-catenin signaling in basal mammary epithelial cells affects mammary development and leads to hyperplasia. Development. 2005;132:267–277. doi: 10.1242/dev.01583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikaelian I, Hovick M, Silva KA, Burzenski LM, Shultz LD, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Cox GA, Sundberg JP. Expression of terminal differentiation proteins defines stages of mouse mammary gland development. Vet Pathol. 2006;43:36–49. doi: 10.1354/vp.43-1-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gimble JM, Pighetti GM, Lerner MR, Wu X, Lightfoot SA, Brackett DJ, Darcy K, Hollingsworth AB. Expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor mRNA in normal and tumorigenic rodent mammary glands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:813–817. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicol CJ, Yoon M, Ward JM, Yamashita M, Fukamachi K, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ. PPARgamma influences susceptibility to DMBA-induced mammary, ovarian and skin carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1747–1755. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suh N, Wang Y, Williams CR, Risingsong R, Gilmer T, Willson TM, Sporn MB. A new ligand for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma), GW7845, inhibits rat mammary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5671–5673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pighetti GM, Novosad W, Nicholson C, Hitt DC, Hansens C, Hollingsworth AB, Lerner ML, Brackett D, Lightfoot SA, Gimble JM. Therapeutic treatment of DMBA-induced mammary tumors with PPAR ligands. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:825–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee LD, Guo Y, Bradbury J, Suster S, Clinton SK, Seewaldt VL. The antiproliferative effects of PPARgamma ligands in normal human mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;78:179–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1022978608125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SS, Pineau T, Drago J, Lee EJ, Owens JW, Kroetz DL, Fernandez-Salguero PM, Westphal H, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of the alpha isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3012–3022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diamond I, Owolabi T, Marco M, Lam C, Glick A. Conditional gene expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice using the tetracycline-regulated transactivators tTA and rTA linked to the keratin 5 promoter. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:788–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Muller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seagroves TN, Krnacik S, Raught B, Gay J, Burgess-Beusse B, Darlington GJ, Rosen JM. C/EBPbeta, but not C/EBPalpha, is essential for ductal morphogenesis, lobuloalveolar proliferation, and functional differentiation in the mouse mammary gland. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1917–1928. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphreys RC, Krajewska M, Krnacik S, Jaeger R, Weiher H, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Rosen JM. Apoptosis in the terminal endbud of the murine mammary gland: a mechanism of ductal morphogenesis. Development. 1996;122:4013–4022. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiyama TE, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ. Regulation of the liver fatty acid-binding protein gene by hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha (HNF1alpha). Alterations in fatty acid homeostasis in HNF1alpha-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27117–27122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters JM, Aoyama T, Cattley RC, Nobumitsu U, Hashimoto T, Gonzalez FJ. Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in altered cell cycle regulation in mouse liver. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1989–1994. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.11.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hennighausen L, Robinson GW. Information networks in the mammary gland. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nrm1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pineda Torra I, Jamshidi Y, Flavell DM, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Characterization of the human PPARalpha promoter: identification of a functional nuclear receptor response element. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1013–1028. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fata JE, Kong YY, Li J, Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Moorehead RA, Elliott R, Scully S, Voura EB, Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Khokha R, Penninger JM. The osteoclast differentiation factor osteoprotegerin-ligand is essential for mammary gland development. Cell. 2000;103:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heikkila M, Peltoketo H, Leppaluoto J, Ilves M, Vuolteenaho O, Vainio S. Wnt-4 deficiency alters mouse adrenal cortex function, reducing aldosterone production. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4358–4365. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brisken C, Ayyannan A, Nguyen C, Heineman A, Reinhardt F, Tan J, Dey SK, Dotto GP, Weinberg RA. IGF-2 is a mediator of prolactin-induced morphogenesis in the breast. Dev Cell. 2002;3:877–887. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HJ, Yoon MJ, Lee J, Penninger JM, Kong YY. Osteoprotegerin ligand induces beta-casein gene expression through the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5339–5344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grimm SL, Contreras A, Barcellos-Hoff MH, Rosen JM. Cell cycle defects contribute to a block in hormone-induced mammary gland proliferation in CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBPbeta)-null mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36301–36309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mouthiers A, Baillet A, Delomenie C, Porquet D, Mejdoubi-Charef N. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha physically interacts with CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBPbeta) to inhibit C/EBPbeta-responsive alpha1-acid glycoprotein gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1135–1146. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delerive P, De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Fruchart JC, Haegeman G, Staels B. DNA binding-independent induction of IkappaBalpha gene transcription by PPARalpha. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1029–1039. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmuth M, Haqq CM, Cairns WJ, Holder JC, Dorsam S, Chang S, Lau P, Fowler AJ, Chuang G, Moser AH, Brown BE, Mao-Qiang M, Uchida Y, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J, Chambon P, Willson TM, Elias PM, Feingold KR. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-beta/delta stimulates differentiation and lipid accumulation in keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:971–983. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters JM, Hennuyer N, Staels B, Fruchart JC, Fievet C, Gonzalez FJ, Auwerx J. Alterations in lipoprotein metabolism in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27307–27312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwertfeger KL, McManaman JL, Palmer CA, Neville MC, Anderson SM. Expression of constitutively activated Akt in the mammary gland leads to excess lipid synthesis during pregnancy and lactation. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1100–1112. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300045-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R, Ben-Ze’ev A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5522–5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Farmer SR. Regulating the balance between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and beta-catenin signaling during adipogenesis. A glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylation-defective mutant of beta-catenin inhibits expression of a subset of adipogenic genes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45020–45027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, Bennett CN, Lucas PC, Erickson RL, MacDougald OA. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science. 2000;289:950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mulholland DJ, Dedhar S, Coetzee GA, Nelson CC. Interaction of Nuclear Receptors with the Wnt/{beta}-Catenin/Tcf Signaling Axis: Wnt You Like to Know. Endocr Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fantl V, Stamp G, Andrews A, Rosewell I, Dickson C. Mice lacking cyclin D1 are small and show defects in eye and mammary gland development. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2364–2372. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Parker SB, Li T, Fazeli A, Gardner H, Haslam SZ, Bronson RT, Elledge SJ, Weinberg RA. Cyclin D1 provides a link between development and oncogenesis in the retina and breast. Cell. 1995;82:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tepera SB, McCrea PD, Rosen JM. A beta-catenin survival signal is required for normal lobular development in the mammary gland. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1137–1149. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsu W, Shakya R, Costantini F. Impaired mammary gland and lymphoid development caused by inducible expression of Axin in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1055–1064. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]