Abstract

The initiation of DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends upon the destruction of the Clb–Cdc28 inhibitor Sic1. In proliferating cells Cln–Cdc28 complexes phosphorylate Sic1, which stimulates binding of Sic1 to SCFCdc4 and triggers its proteosome mediated destruction. During sporulation cyclins are not expressed, yet Sic1 is still destroyed at the G1-/S-phase boundary. The Cdk (cyclin dependent kinase) sites are also required for Sic1 destruction during sporulation. Sic1 that is devoid of Cdk phosphorylation sites displays increased stability and decreased phosphorylation in vivo. In addition, we found that Sic1 was modified by ubiquitin in sporulating cells and that SCFCdc4 was required for this modification. The meiosis-specific kinase Ime2 has been proposed to promote Sic1 destruction by phosphorylating Sic1 in sporulating cells. We found that Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 at multiple sites in vitro. However, only a subset of these sites corresponds to Cdk sites. The identification of multiple sites phosphorylated by Ime2 has allowed us to propose a motif for phosphorylation by Ime2 (PXS/T) where serine or threonine acts as a phospho-acceptor. Although Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 at multiple sites in vitro, the modified Sic1 fails to bind to SCFCdc4. In addition, the expression of Ime2 in G1 arrested haploid cells does not promote the destruction of Sic1. These data support a model where Ime2 is necessary but not sufficient to promote Sic1 destruction during sporulation.

Keywords: cyclin dependent kinase, Ime2, Sic1, sporulation

Abbreviations: Cdk, cyclin dependent kinases; CIP, calf intestinal phosphatase; Cln, cyclin; DTT, dithiothreitol; HA, haemagglutinin; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; IEF, isoelectric focussing; Mbp, maltose binding protein; MS/MS, tandem MS; SCF, SKP1–Cullin–F–box; SPM, sporulation medium

INTRODUCTION

The eukaryotic cell division cycle is driven by the periodic accumulation of factors that promote the transition between discrete cell cycle phases [1,2]. The efficacy of these positively acting factors is balanced by inhibitors that restrain cell cycle progression and impose temporal order upon cell cycle events [3]. Cdks (cyclin dependent kinases) are the primary factors that promote progress through the cell cycle [1,2]. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cdc28 is the Cdk that provides the impetus for transition between cell cycle phases [1]. Cdc28 is activated at discrete times in the cell cycle by association with sequentially expressed cyclin subunits. The G1 cyclins, Cln1, Cln2 and Cln3, have specific roles in the G1-phase, whereas Clb1–Clb6 promote the S-phase, the G2-phase and mitosis [4].

Accumulation of the kinase activity associated with Clb5 and Clb6 is critical to ensure the timely initiation of DNA replication [5]. In addition to transcriptional control and regulated protein instability, the activity of Clb5 and Clb6 is governed by the Cdk inhibitor Sic1 [5]. In mitotically proliferating cells Sic1 accumulates in mitosis and persists until cells progress to the G1-/S-phase boundary, at which time Sic1 is degraded [5,6]. Sic1 destruction is dependent upon Cln1– and Cln2–Cdc28 complexes that phosphorylate Sic1 at multiple Cdk consensus sites (S/T)PX(K/R) [7]. The phosphorylated Sic1 binds to Cdc4, a component of the SCF (SKP1–Cullin–F box) ubiquitin ligase, and is ubiquitinylated, which targets Sic1 for destruction by the proteosome [8]. Destruction of Sic1 releases active Clb5– and Clb6–Cdc28, which subsequently promote DNA replication [9].

The combined effects of sequential dependent events and cell cycle checkpoints enforce the organization of the cell division cycle [10]. However, when cells initiate differentiation pathways, many aspects of cell cycle regulation undergo extensive reorganization [11,12]. A dramatic example of cell cycle reorganization is observed during gametogenesis [12,13]. Gamete formation by S. cerevisiae is referred to as sporulation. The formation of haploid spores from a parental diploid cell involves progress through S-phase and extensive homologous recombination prior to two sequential rounds of chromosome division, MI (meiosis I) and MII (meiosis II) [13].

The decision of whether to enter a mitotic cell division cycle or to initiate sporulation is made in G1-phase [14]. In the absence of sufficient nutrients the CLN1, CLN2 and CLN3 genes are repressed and cells arrest in G1 [15]. Coincident with the repression of CLN genes, sporulation-specific genes are activated. One of the early meiotic genes is IME2, which encodes a protein kinase [16]. Ime2 is required for full activation of the early and middle sporulation genes and for timely premeiotic DNA replication [17,18]. It has been postulated that Ime2 might perform many functions in sporulation that are assigned to Cln–Cdc28 in proliferating cells [19].

Although Cln cyclins are not required for sporulation, the activation of Clb5–Cdc28 and Clb6–Cdc28 kinase complexes is essential for premeiotic DNA replication [19–21]. Either deletion of both CLB5 and CLB6 or the expression of a stabilized Sic1, which inhibits Clb5– and Clb6–Cdc28 activity, impedes premeiotic DNA replication, preventing sporulation and ultimately resulting in cell death [19,20]. Thus the timely inactivation of Sic1 is necessary for sporulation and sexual reproduction in S. cerevisiae.

During sporulation Sic1 degradation is independent of Cdc28 but requires Ime2 kinase activity [19,21]. Although the relationship between IME2 and SIC1 has implicated Ime2 in directly regulating Sic1 stability, this function has not been rigorously established. We have found that Sic1 destruction is dependent upon Ime2 and SCFCdc4. Ime2 is capable of phosphorylating Sic1 in vitro, however only a subset of the sites phosphorylated by Ime2 correspond to Cdk sites. Additionally, we have found that phosphorylation of Sic1 by Ime2 in vitro is insufficient to promote its binding to Cdc4. Thus, whereas Ime2 is necessary to promote the timely destruction of Sic1 during sporulation, Ime2 alone is insufficient to trigger this event.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions

The yeast strains used in this study and their relevant genotypes are listed in Table 1. All SK1 strains were derived from the parental strains DSY1030 (MATa lys2 ho::LYS2 ura3 leu2::hisG trp1::hisG arg4-Bgl his4-X) and DSY1031 (MATα lys2 ho::LYS2 ura3 leu2::hisG trp1::hisG arg4-Nsp his4-B) by standard genetic procedures [22]. The ime2::TRP1 mutant and clb5::KANR clb6::TRP1 strains have been described previously [20,23]. Yeast were routinely propagated in YEP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone and 30 mg/l adenine) supplemented with 2% glucose (YEPD), 2% potassium acetate (YEPKAc) or 2% galactose (YEPGal). The SPM (sporulation medium) used in this study was 1% potassium acetate. Synchronous cultures of sporulating cells were generated as described previously [20]. The plasmids carrying CUP1 regulated UbHis−MYC−RA (pUB223) and CUP1-UbMYC−RA (pUB204) have been described previously [24]. The CUP1-UbHis−4XMYC−RA plasmid was constructed by introducing a Not1 site into the N-terminal coding region of the MYC epitope in pUB223 and inserting a 3XMYC cassette in frame with the 6-hisMYC coding sequence. The Mbp (maltose binding protein)–Sic1 fusion protein was generated by ligating a PCR-generated SIC1HA6HIS fragment into pMAL-C2. Vectors for the expression of 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P were created by ligating PCR-generated SIC1 and SIC10P open reading frames into the expression plasmid pET19b. The PCR-generated open reading frames were sequenced in their entirety to confirm the absence of any confounding mutations.

Table 1. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study.

All strains are in the SK1 genetic background [42] derived from DSY1030 and DSY1031 [20], except DSY1359 which is derived from BF264-15Daub, the full genotype has been reported previously [43].

| DSY1089 | a/α |

| DSY1357 | a/α sic1::SIC1HA/sic1::SIC1HA |

| DSY1170 | a/α cdc28-4/cdc28-4 sic1::SIC1HA/sic1::SIC1HA |

| DSY1290 | a/α cdc4-3/cdc4-3 sic1::SIC1HA/sic1::SIC1HA |

| DSY1366 | a/α ime2::TRP1/ime2::TRP1 sic1::SIC1HA/sic1::SIC1HA |

| DSY1049 | a/α clb5::KANR/clb5::KANRclb6::TRP1/clb6::TRP1 sic1::SIC1HA/sic1::SIC1HA |

| DSY1320 | a/α ime2::LEU2/ime2::LEU2 sum1::TRP1/sum1::TRP1 sic1::SIC1HA/sic1::SIC1HA |

| DSY1361 | a/α cdc4-3/cdc4-3 URA3::IME2-SIC1HA/URA3::IME2-SIC1HA |

| DSY1420 | a/α cdc4-3/cdc4-3 URA3::IME2-SIC10PHA/URA3::IME2-SIC10PHA |

| DSY1325 | a/α cdc4-3/cdc4-3 URA3::CUP1-SIC1HA6his/URA3::CUP1-SIC1HA6hisx |

| DSY1516 | a/α URA3::IME2-SIC1HA/URA3::IME2-SIC1HA |

| DSY1514 | a/α URA3::IME2-SIC10PHA/URA3::IME2-SIC10PHA |

| DSY1359 | a bar1 cln1 cln2 cln3 leu2::GAL-CLN3 SIC1HA YCpCUP1-IME2MYC |

| DSY1520 | a/α sic1::SIC1A10-HA/sic1::SIC1A10-HA |

| DSY1552 | a/α cdc4-3/cdc4-3 sic1::KanR/sic1::KanRSIC1A10-HA/SIC1A10-HA |

Protein extracts, purification, Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Protein extracts for Western analysis were prepared as described previously [23]. Samples corresponding to 25 μg of protein were separated by electrophoresis through SDS/PAGE (10% gels), transferred to PVDF membranes, and blocked by incubation in TBS-T [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl and 0.25% Tween 20] supplemented with 5% (w/v) non-fat dried skimmed milk powder. Proteins were detected with the following antibodies: α-HA (haemagglutinin) acsites fluid 1:10000 (Babco), α-MYC ascites fluid 1:10000 (Babco), α-PSTAIRE 1:10000 (Sigma), α-Sic1 1:500. All primary antibodies were detected by incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP (horse-radish peroxidase), followed by enhanced chemiluminescence [23]. Immunoprecipitation and histone H1 kinase assays were carried out as described previously [23,25]. Protein samples for the detection of ubiquitinated Sic1 were made from 5×108 cells that had been induced to initiate sporulation by resuspending them in SPM at a density of 3×107/ml. After 30 min the culture was shifted to 37 °C and copper sulfate was added to a final concentration of 200 μM. The cells were harvested by centrifugation after 2 h. Extracts were prepared and ubiquitinated Sic1 was detected as described previously [24]. Extracts for two-dimensional electrophoresis were made by breaking cells in 40 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 8 M urea, 4% CHAPS, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 60 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 20 μg/ml each of leupeptin, pepstatin, aprotinin and 1 mM PMSF. These samples were spiked with 0.1 ng of purified Mbp1–Sic1HA6his to allow the alignment and comparison of migration on different IEF (isoelectric focusing) gels. Following IEF in the first dimension and electrophoresis through SDS/PAGE (10% gels) in the second dimension, Sic1–HA and Mbp–Sic1HA were detected by Western blot with HRP-conjugated α-HA antibodies. Mbp–Sic1HA6his was purified from one litre of Escherichia coli BL21 by sequential chromatography over amylose and nickel charged sepharose as described previously [7]. The 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P proteins were produced in E. coli BL21–DE3. The recombinant proteins were expressed and purified as described previously [26]. The purified 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P were dialysed against 50 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.8), 50 mM NaCl and 20% glycerol, and subsequently stored at −80 °C.

Analysis of Sic1 binding to SCF

The ability of Sic1 to bind SCF complexes was tested essentially as described previously [8]. The 6his–Sic1 or 6his–Sic10P (0.5 μg) was phosphorylated in vitro with either Ime2–Myc or Cln2-HA–Cdc28 complexes. Sic1 was mixed with 10 μl of Skp1–Cdc4 beads (generously donated by Dr Michael Tyers, Bioinformatics and Functional Genomics, University of Toronto, Canada). The bead bound fraction was washed three times with 1 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P40, 10 mM NaF and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate]. Both the bound and unbound fraction were resuspended in SDS sample buffer and subjected to gel electrophoresis. The bound Sic1 was detected either by Western blot with α-Sic1 antibodies or the dried gels were exposed to a phosphorimaging screen that was subsequently scanned on a STORM 860 phosphorimager.

Analysis of DNA content by flow cytometry

Cellular DNA content was determined by flow cytometry essentially as described [20]. Approximately 5×108 cells from synchronously sporulating cultures were harvested by centrifugation and fixed in 70% ethanol. Cell samples were prepared for flow cytometry as described [20], and were analysed on a FACScan instrument (BD Biosciences).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Protein extracts were prepared for IEF by precipitation using a two-dimensional clean up kit (Amersham Biosciences) and were resuspended in 8 M urea, 2% CHAPS, 50mM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 1% (v/v) IPG buffer pH range 3–10 (Amersham Biosciences). The samples were applied to immobilized pH 3–10 non-linear gradient strips, and loading was achieved by active rehydration at 20 V for 12 h in an Ettan IPGphor IEF system. The samples were then focused in a three-step protocol: 500 V for 1 h, 1000 V for 1 h, 8000 V until a total of 16000 Vh was achieved. The strips were equilibrated in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.8), 6 M urea, 30% glycerol, 2% SDS and 100 mM DTT for 15 min. Strips were then positioned for SDS/PAGE (10% gel) and electrophoresed. The separated proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes and subjected to Western analysis with HRP-conjugated α-HA antibodies.

Detection of phosphorylation by MS

To identify Sic1 residues phosphorylated by Ime2 in vitro, 5 μg of purified Mbp–Sic1HA6his was phosphorylated with immobilized Ime2 in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM ATP. Following reverse-phase chromatography over a Zorbax 300B C8 column (2.1 mm×150 mm) at 70 °C, the purified protein was digested with modified trypsin for 16 h in 1.5 M urea and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.5). The peptides were then analysed by LC/MS/MS on a Micromass Q-Tof-2™ coupled to a Waters CapLC capillary HPLC (Waters Corp U.S.A.). In a second experiment 2 μg of 6his–Sic1 was phosphorylated with Ime2 as described above and subjected to MudPIT analysis using a Finnigan LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with a nano-LC electrospray ionization source as described previously [27]. Tryptic phospho-peptide mapping was performed using a Hunter two-dimensional thin-layer electrophoresis apparatus [28].

RESULTS

Ime2 and SCFCdc4 regulate Sic1 stability during sporulation

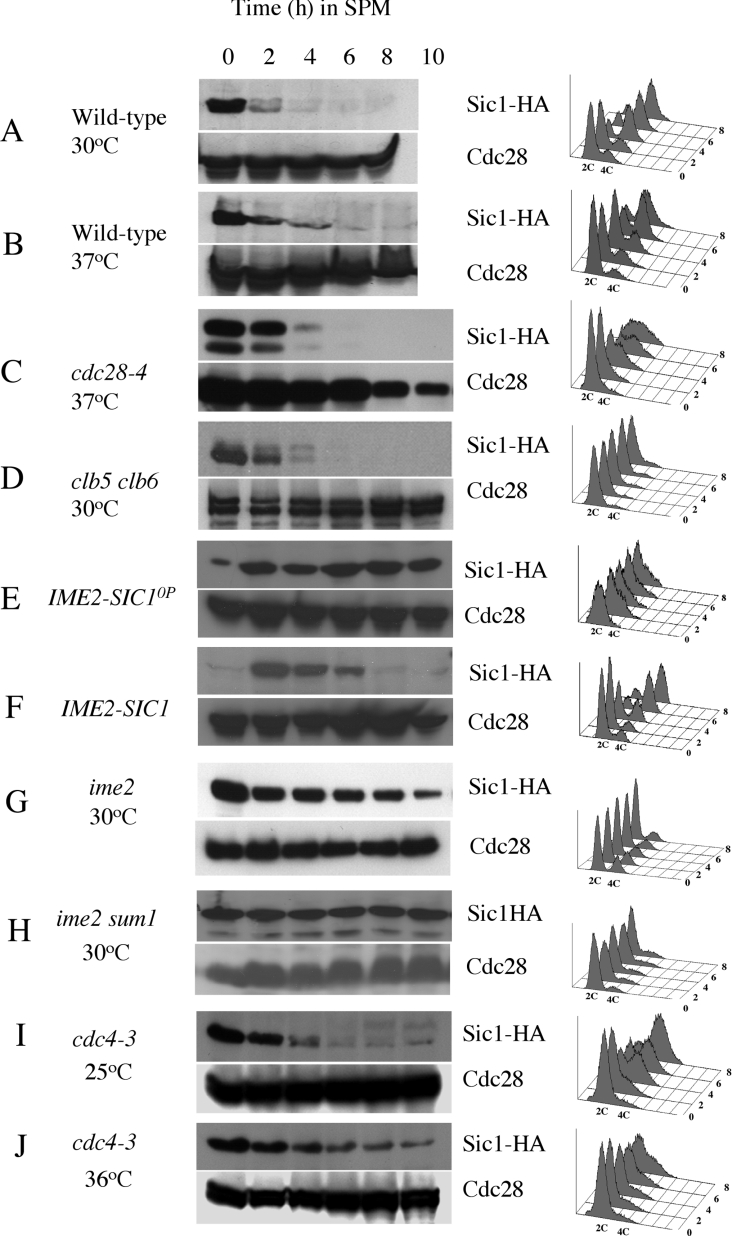

In the current study we have investigated the stability of the Cdk inhibitor Sic1 in cells progressing through meiosis and sporulation. Sic1 was effectively degraded within 4 h of initiating sporulation in wild-type cells at 30 °C (Figure 1A). At 37 °C, Sic1 was also degraded, although some of the protein persisted for up to 4 h (Figure 1B). Consistent with the destruction of Sic1, genomic DNA was replicated at both temperatures (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Sic1 stability during sporulation is dependent upon Ime2, SCFCdc4 and Cdk sites.

Diploid cells homozygous for the mutations indicated to the left of each panel were induced to initiate sporulation at the temperatures indicated. At the indicated time points, samples were taken to monitor Sic1 (upper panel of each set), and Cdc28 (lower panel of each set) abundance by Western blot. DNA replication was monitored by flow cytometry of propidium iodide stained cells shown to the right of each panel. The time (h) is indicated to the right of the flow cytometry data.

During mitotic proliferation Sic1 degradation is dependent upon its being phosphorylated by Cln–Cdc28 kinase complexes [7]. However, when a temperature-sensitive cdc28-4 strain was induced to sporulate at the non-permissive temperature of 37 °C, Sic1 was still effectively degraded (Figure 1C). The disappearance of Sic1 in cdc28-4/cdc28-4 cells at 37 °C occurred with similar timing to Sic1 degradation in wild-type cells at 37 °C (compare Figure 1B with Figure 1C). Consistent with loss of Sic1, cdc28-4/cdc28-4 diploids initiated DNA replication at the non-permissive temperature of 37 °C. Although the completion of DNA replication was delayed relative to wild-type cells at the permissive temperature, a significant portion appeared to complete replication (Figure 1C).

It has never been demonstrated whether or not Sic1 degradation during sporulation is dependent upon regulated phosphorylation. Cyclins are not required for sporulation [19]. In contrast, deletion of the cyclins CLB5 and CLB6 blocks entry into meiotic S-phase [19,20]. We considered it possible that Clb5- and Clb6-associated kinase activity might be responsible for triggering Sic1 degradation during sporulation. However, despite the G1 arrest experienced by the clb5/clb6 diploids, Sic1 was degraded with similar timing to that seen in wild-type cells (compare Figure 1A with Figure 1D). Thus, degradation of Sic1 during sporulation is not dependent on either Cln–Cdc28 or Clb5–Cdc28 kinase activity.

The lack of requirement for Cdc28 activity to promote Sic1 destruction during sporulation was surprising, since a mutant Sic1 that lacked Cdk phosphorylation sites caused G1 arrest during sporulation [20]. To further investigate this we placed both Sic1 and Sic10P (a mutant version of Sic1 lacking all nine consensus Cdk phosphorylation sites) under the regulation of the meiosis-specific IME2 promoter. Placing Sic10P under the control of a meiosis-specific promoter was necessary since expression of Sic10P arrests proliferating cells [8]. When the cells harbouring these constructs were induced to sporulate, Sic10P accumulated to high levels and remained stable throughout the time course of the experiment (Figure 1E). DNA replication in these cells was hindered and no cells with a 4C DNA content were detected (Figure 1E). In contrast, when wild-type Sic1 was expressed under the regulation of the Ime2 promoter, Sic1 accumulated early during sporulation but was degraded 4–6 h into sporulation and the cells completed DNA replication (Figure 1F). Sic10P was also expressed in sporulating cdc4/cdc4 diploids at the non-permissive temperature and in an ime2/ime2 diploid. Within the resolution that is allowed by Western blots we could not discern any significant differences between wild-type cells and any of these mutants in the persistence of the Sic10P (results not shown), implying that the Cdk sites in Sic1 are the primary determinants of its stability during sporulation.

Ime2 is a meiosis-specific protein kinase that has been proposed to promote the degradation of Sic1 during sporulation [19]. Consistent with this proposal, we observed that deletion of IME2 significantly stabilized Sic1 when cells were induced to initiate sporulation (Figure 1G). This suggested that the kinase activity associated with Ime2 might be required for efficient degradation of Sic1 during sporulation. In the ime2/ime2 mutant cells, pre-meiotic DNA replication was delayed, and within the time frame of this experiment very little DNA replication was detected (Figure 1G). However, at later time points a significant proportion of the cells accumulated with a 4C DNA content, consistent with the gradual loss of Sic1 (results not shown). In addition to promoting DNA replication, Ime2 is required for expression of the middle sporulation genes [29]. We considered it possible that Ime2 might promote Sic1 destruction by inducing the expression of another protein kinase encoded by a middle sporulation gene. To test this possibility we generated a diploid strain lacking both IME2 and the transcriptional repressor SUM1. The deletion of SUM1 allows the expression of middle sporulation genes in an ime2/ime2 mutant [29]. However, in these cells Sic1 was stabilized to a similar degree to that seen in ime2/ime2 mutants and no acceleration of DNA replication was observed (Figure 1H). Thus Sic1 degradation during sporulation is dependent upon Ime2 and cannot be stimulated by allowing the expression of proteins encoded by the middle sporulation genes.

In mitotically proliferating cells, phosphorylated Sic1 has an elevated affinity for Cdc4 and the SCF complex, making it a substrate for ubiquitin-mediated degradation [30]. Cells harbouring the temperature sensitive cdc4-3 allele effectively degraded Sic1 and replicated DNA during sporulation at the permissive temperature of 25 °C (Figure 1I). In contrast, at the non-permissive temperature (36 °C) Sic1 was stabilized and persisted for at least 10 h (Figure 1J). In addition, meiotic DNA replication was significantly delayed (Figure 1J). The same stabilization of Sic1 was observed when Cdc53, another component of the SCF was inactivated during sporulation (results not shown). These observations indicate that Sic1 degradation requires the function of the SCF complex both during mitotic proliferation and during sporulation.

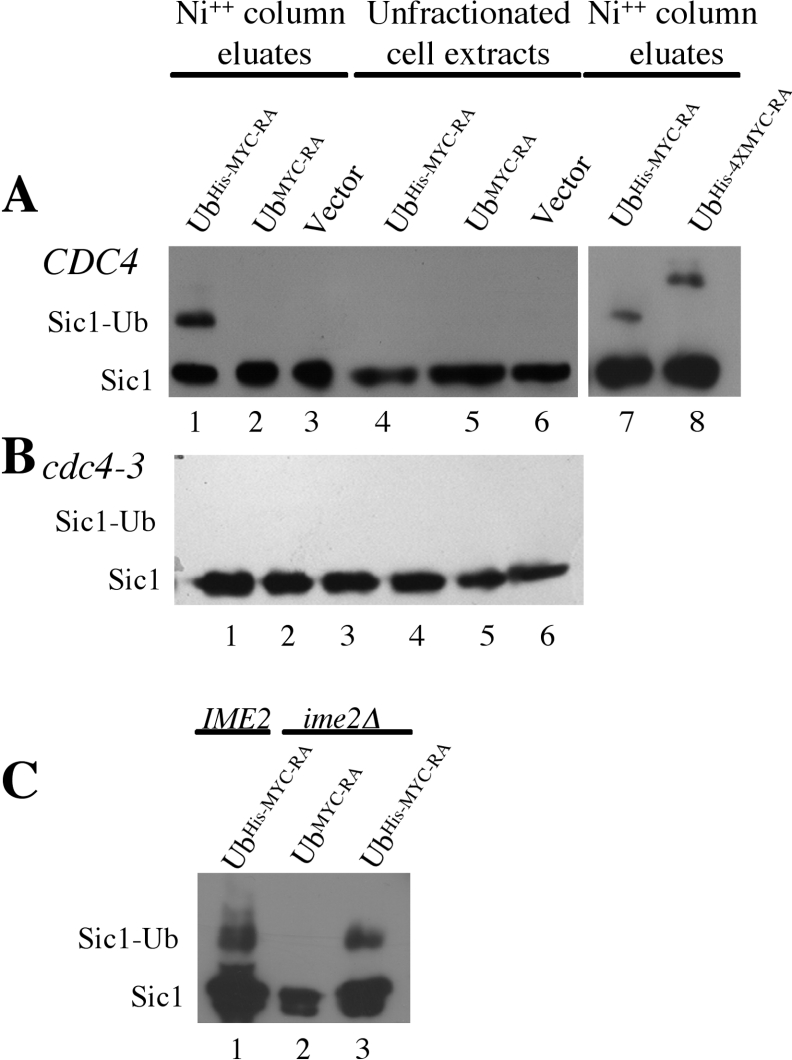

Sic1 is ubiquitinated during sporulation

The requirement for SCFCdc4 to promote Sic1 degradation during sporulation implies that Sic1 would be ubiquitinated. To determine if Sic1 was subject to ubiquitination in sporulating cells, we expressed a mutant form of ubiquitin that encoded Lys48 changed to arginine (K48R) and Gly76 changed to alanine (G76A). This mutant ubiquitin (UbHis−MYC−RA) can be ligated to substrate proteins but cannot be conjugated to another ubiquitin molecule by virtue of the K48R mutation, and thus prevents the formation of polyubiquitin chains [24,31]. This should enhance the ability to detect the conjugates and may partially stabilize the substrate proteins. In addition, this mutant ubiquitin cannot be cleaved from the substrate protein by ubiquitin-specific peptidases due to the G76A mutation [32]. This version of ubiquitin was fused to an MYC epitope and to six histidine residues to allow for detection and purification. When the modified ubiquitin was expressed in sporulating cells and captured on nickel-charged sepharose beads, both full-length Sic1 and a more slowly migrating version of Sic1 could be detected in the eluates (Figure 2A, lane 1). Despite extensive washing, some unmodified Sic1 was bound to the resin; however, the slower migrating form of Sic1 was only detected when the cells expressed UbHis−MYC−RA (Figure 2A, lane 1). Nickel column eluates from extracts of cells that carried a plasmid expressing Ub MYC−RA or carrying the vector alone did not display a slower migrating form of Sic1 (Figure 2A, lanes 2 and 3). The modified ubiquitin was clearly a minor portion of the total Sic1 in the cells as it was not easily detectable in the unfractionated cell extracts (Figure 2A, lanes 4–6). We made several attempts to confirm that the slower migrating form of Sic1 was in fact conjugated to UbHis−MYC−RA by immunoprecipitating Sic1 from the nickel column eluates, and then probing the immunoprecipitate with anti-MYC antibodies to detect the ubiquitin. However, the Sic1–ubiquitin conjugate could not be reliably detected in this fashion. Therefore, we generated a version of ubiquitin that was fused to four copies of the MYC epitope and six histidine residues. When UbHis−4XMYC−RA was expressed in sporulating cells we could detect modified Sic1 that, as expected, migrated more slowly than Sic1 isolated from cells expressing UbHis−MYC−RA, confirming that the more slowly migrating Sic1 was indeed conjugated to ubiquitin (Figure 2A, lanes 7 and 8).

Figure 2. Sic1 is ubiquitinated in vivo during sporulation.

(A) Wild type diploid cells, or (B) cdc4-3/cdc4-3 diploid cells harbouring UbHis−MYC−RA (lanes 1, 4 and 7), UbMYC−RA (lanes 2 and 5), UbHis−4xMYC−RA (lane 8) or an empty vector (lanes 3 and 6) were inoculated into SPM and the tagged ubiquitin was induced (30 °C for wild-type cells and 36 °C for cdc4-3/cdc4-3 mutant cells). Nickel column eluates (lanes 1–3, 7 and 8) and unfractionated extracts (lanes 4–6) were probed by Western blot for Sic1–HA. Some unmodified Sic1–HA bound to the column in all cases, however the slower mobility forms of Sic1 were identified only in lysates containing the 6his tagged ubiquitin (lanes 1, 7 and 9). (C) An ime2/ime2 diploid strain harboring UbMYC−RA (lane 2) or UbHIS−MYC−RA (lane 3) and an IME2/IME2 strain harbouring UbHIS−MYC−RA (lane 1) were induced to sporulate and extracts were assayed for Sic1 ubiquitination.

Based upon the stabilization of Sic1 in cdc4-3/cdc4-3 cells that had been induced to sporulate at the non-permissive temperature, we anticipated that the ubiquitination of Sic1 in sporulating cells would be dependent upon SCF activity. Indeed when UbHis−MYC−RA was expressed in cdc4-3/cdc4-3 diploids that had been induced to sporulate at the non-permissive temperature we did not detect ubiquitinated Sic1 in the nickel column eluate (Figure 2B, lanes 1–3), despite the fact that unmodified Sic1 could be detected (Figure 2B, lanes 1–6). These data demonstrate that Sic1 was modified by ubiquitination in sporulating cells and that SCFCdc4 was required for this modification.

In the absence of Ime2 activity the destruction of Sic1 and the initiation of DNA replication are delayed, but both still occur. To determine whether Sic1 was being ubiquitinated in the absence of Ime2 activity we expressed UbHis−MYC−RA or UbMYC−RA in an ime2/ime2 diploid and assayed Sic1 ubiquitination as described above, however in this case the cells were harvested 5 h into the sporulation time course. Modified Sic1 could be isolated from ime2/ime2 mutants that expressed UbHis−MYC−RA but not from UbMYC−RA (Figure 2C, lanes 2 and 3). The more slowly migrating form of Sic1 isolated from these cells displayed mobility similar to the modified Sic1 that could be isolated from wild-type cells (Figure 2C, compare lane 1 with lane 3). Thus Sic1 ubiquitination occurs in vivo in the absence of Ime2 activity, consistent with the idea that Ime2 stimulates but is not essential to promote the destruction of Sic1.

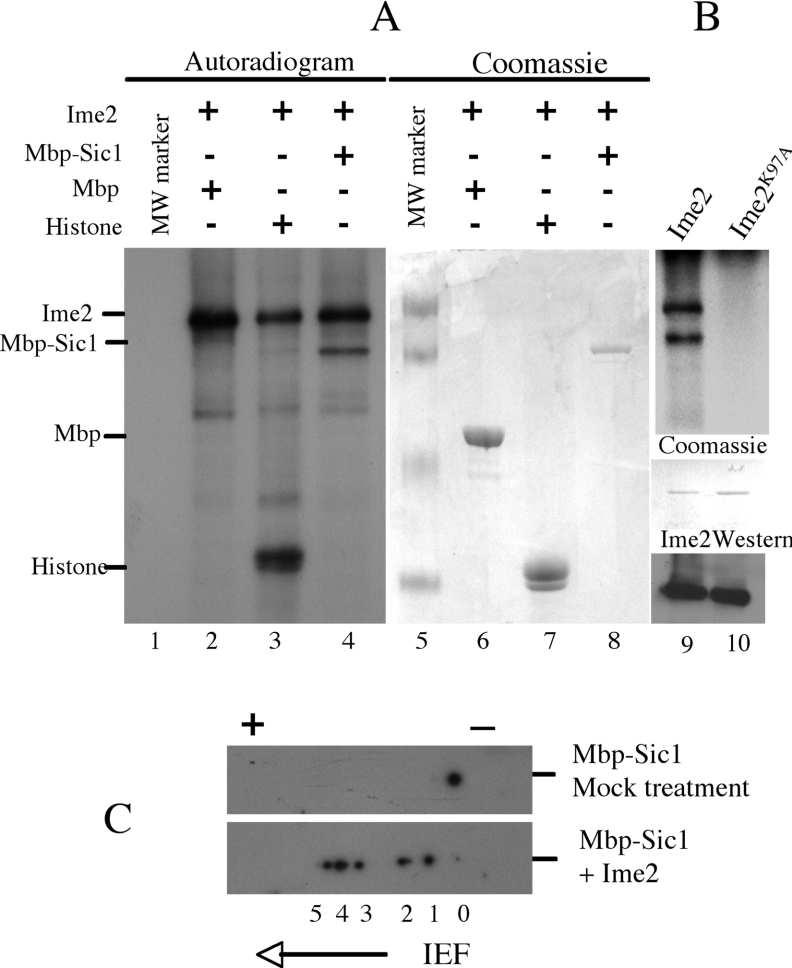

Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 in vitro

To determine whether Sic1 might be a substrate for Ime2 kinase activity we assayed the ability of Ime2 to phosphorylate a recombinant Mbp–Sic1 fusion protein (Mbp–Sic1HA6his) in vitro. Following separation of the reactants by gel electrophoresis the phosphate incorporation was detected by autoradiography (Figure 3A, lanes 1–4) and the proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining (Figure 3A, lanes 5–8). As has been previously observed Ime2 autophosphorylates and displayed a prominent band on the autoradiogram (Figure 3A, lane 2). Ime2 did not incorporate 32P into the Mbp alone (Figure 3A, lane 2). However, Ime2 could incorporate 32P into Histone H1 and into the Mbp–Sic1HA6his fusion protein (Figure 3A, lanes 3 and 4). Since Ime2 failed to incorporate phosphate into Mbp1 alone it is likely that the Sic1 portion of the fusion protein was being phosphorylated. When Mbp–Sic1HA6his was treated with a catalytically inactive mutant of Ime2 (Ime2K97A) no 32P was incorporated (Figure 3B, compare lane 9 with lane 10). This implies that the phosphate incorporation detected was dependent upon Ime2 activity.

Figure 3. Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 in vitro.

(A) Ime2–MYC immunoprecipitated from sporulating yeast cells was mixed with Mbp (lanes 2 and 6), Histone H1 (lanes 3 and 7) or Mbp–Sic1HA (lanes 4 and 8) in kinase reactions along with [γ32P] ATP. Molecular mass markers were included (lanes 1 and 5). The phosphorylated proteins in each reaction were visualized by autoradiography (lanes 1–4) and the same gel was stained with Coomassie Blue to visualize the input proteins (lanes 5–8). (B) Mbp–Sic1HA was also used as a substrate in kinase reactions with either Ime2–MYC (lane 9) or Ime2K97A–MYC (lane 10). The phosphorylated products were visualized by autoradiography (upper panel), and the input proteins were stained with Coomassie Blue. The Ime2–MYC or Ime2K97A–MYC were visualized by Western blot. (C) Western blots of two-dimensional gels loaded with Mbp–Sic1HA either mock treated (upper panel) or treated with Ime2 (lower panel).

Since the regulated destruction of Sic1 in vegetatively growing cells requires that Cln2–Cdc28 phosphorylate at least six Cdk sites in Sic1, we investigated whether Ime2 could phosphorylate multiple sites on Sic1. Mbp–Sic1HA6his that had been treated with an anti-MYC immunoprecipitate from untagged sporulating yeast migrated as a single species in two-dimensional gel analysis (Figure 3C). In contrast Mbp–Sic1HA6his that had been treated with Ime2–MYC displayed multiple spots consistent with differently phosphorylated species (Figure 3C). In this experiment we could detect six independent Mbp1–Sic1HA6his species labeled 0–5, with 0 corresponding to the unmodified protein and 1–5 migrating toward the acidic end of the IEF gel, indicative of an increasing number of phosphorylation events (Figure 3C).

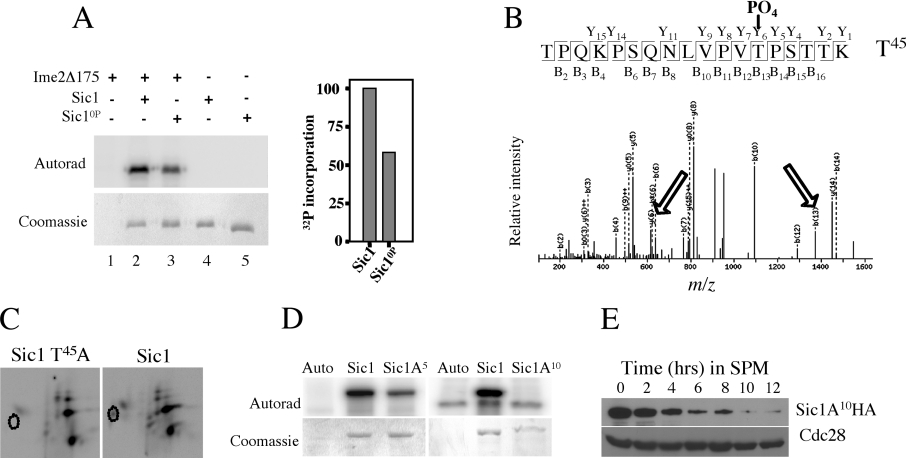

Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 at both Cdk consensus phosphorylation sites and non-Cdk sites

Since Ime2 has been implicated in promoting the destruction of Sic1 during sporulation, we wanted to determine whether Ime2 could phosphorylate Sic1 at Cdk consensus sites in vitro. We mixed 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P (a Sic1 mutant in which all nine Cdk phosphorylation sites were changed to non-phosphorylatable residues) with Ime2Δ175 (a truncated but fully active form of Ime2) [23] in kinase reactions. The incorporated 32P was visualized by autoradiography (Figure 4A, upper panel), and the proteins were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining (Figure 4A, lower panel). No phosphorylated proteins the size of Sic1 could be detected in the Ime2 immunoprecipitate alone (Figure 4A, lane 1). In contrast, Ime2 incorporated 32P into both 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P (Figure 4A, upper panel lanes 2 and 3). More 32P was incorporated into 6his–Sic1 than was incorporated into 6his–Sic10P, despite the fact that equal amounts of 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P were used as substrate (Figure 4A, lower panel, lanes 2, 3). Quantification of the phosphorylated 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P demonstrated that Ime2 kinase incorporated almost twice as much 32P into 6his–Sic1 than was incorporated into 6his–Sic10P (Figure 4A, upper panel lanes 2 and 3 and also see bar graph). The most likely explanation for this result is that Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 at both Cdk consensus sites and other sites.

Figure 4. Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 at PXS/T sites.

(A) Upper panel: an autoradiogram of 6his–Sic1 and 6his–Sic10P treated with Ime2Δ175. (A) Lower panel: the same gel stained with Coomassie Blue to visualize the input proteins. The relative incorporation of phosphate into Sic1 and Sic10P is indicated in the histogram on the right. (B) MS/MS spectra of a Sic1 peptide containing Thr45 phosphorylated by Ime2 in vitro. The fragment ions that were identified are shown in the upper panel. Fragment ions that display a loss of 98 Da, corresponding to loss of a phosphate and water, are indicated by the arrows. (C) Tryptic phospho-peptide maps of Mbp–Sic1 and Mbp–Sic1T45A. The absence of one major spot in the Sic1T45A sample is outlined. (D) Upper panel: an autoradiogram showing 32P incorporated into Sic1A5 and Sic1A10, the gels stained with Coomassie blue are in the lower panel. (E) Western blot of Sic1A10–HA during sporulation. Cdc28 abundance was monitored as a loading control.

Identification of Ime2 phosphorylation sites in Sic1

To identify the sites on Sic1 phosphorylated by Ime2, we subjected in vitro phosphorylated Sic1 to analysis by tandem MS (MS/MS). This analysis unambiguously identified Thr45, Thr48, Ser146, Thr173 and Ser201 as phosphorylated residues (Table 2). The spectra obtained for the Thr45-containing peptide and an illustration of the fragment ions that were identified are shown in Figure 4(B). The phosphorylation site on this peptide was confirmed by the loss of 98 Da, corresponding to the loss of both a phosphate and water from Thr45. The y6 and b13 ions displaying this loss are indicated with arrows. To further test whether Thr45 was phosphorylated in vitro by Ime2 we mutated Thr45 to alanine and then phosphorylated Sic1 or Sic1T45A with Ime2 in vitro. Tryptic phospho-peptide mapping revealed the loss of a single spot, consistent with phosphorylation on Thr45 (Figure 4C). Thr45 and Thr173 correspond to residues phosphorylated by Cln/Cdc28, however Thr48 and Ser146 do not. Although not all of these sites lie within a consensus Cdk motif (S/T)P, they do lie within the motif PX(S/T), where serine or threonine functions as the phospho-acceptor. This motif overlaps with some of the Cdk sites in Sic1 but, as in the case of Thr48 and Ser146, also occurs independently of a Cdk motif. This may explain the ability of Ime2 to phosphorylate Sic1 and Sic10P but show a reduction in phosphate incorporation into Sic10P.

Table 2. Sic1 peptides phosphorylated by Ime2.

Phosphorylated residues that could be unambiguously identified are indicated within the peptide sequence in bold. The numbers in parentheses flanking the peptide sequences correspond to the residue number in Sic1. *For some peptides insufficient ion data were generated to unambiguously identify the site of phosphorylation.

| Mass (Da) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Identified | Residue | |

| Peptides phosphorylated in vitro | |||

| (33)TPQKPSQNLVPVTPSTTK(50) | 2004.20 | 2004.37 | Thr45 |

| (33)TPQKPSQNLVPVTPSTTK(50) | 2004.20 | 2004.49 | Thr48 |

| (135)GEVLLPPSRPTSAR(148) | 1559.79 | 1559.72 | Ser146 |

| (166)IIKDVPGTPSDKVIT(180) | 1662.87 | 1662.89 | Thr173 |

| (198)SQESEDEEDIIINPVR(212) | 1952.84 | 1952.98 | Ser201 |

| Peptides phosphorylated in vivo during sporulation | |||

| (33)TPQKPSQNLVPVTPSTTK(50) | 2004.20 | 2004.22 | Thr45 |

| (2)TPSTPPR(8) | 1103.47 | 1103.50 | * |

| (169)DVPGTPSDK(177) | 995.41 | 995.39 | * |

| (37)PSQNLVPVTPSTTK(50) | 1548.77 | 1548.82 | * |

| (198)SQESEDEEDIIINPVR(212) | 1952.84 | 1952.86 | Ser201 |

The ability of Ime2 to phosphorylate Sic1 in vitro suggested that the same residues might also act as phospho-acceptors in vivo. To determine if Cdk consensus sites were being phosphorylated in vivo during sporulation we purified Sic1 from cdc4-3/cdc4-3 diploid cells that had been induced to sporulate. Analysis of the in vivo phosphorylated Sic1 by MS/MS unambiguously identified Thr45 and Ser201 as phosphorylated residues (Table 2). Additional phosphopeptides containing Thr5, Thr173 and Thr48 were identified but we could not unambiguously identify the phosphorylated residue (Table 2).

The five residues identified as phosphorylation sites were mutated to non-phosphorylatable alanine residues, and the mutant protein (Sic1A5) was treated with Ime2 kinase in vitro. Ime2 incorporated only 25% as much 32P into the mutant Sic1 as the wild type (Figure 4D). This indicated that the residues mutated were bona fide in vitro phosphorylation sites (Figure 4D). Since Ime2 could phosphorylate Sic1A5 we mutated five more serine or threonine residues in Sic1 that resided within PXS/T motifs: Thr5, Thr9, Ser63, Thr85 and Thr148, to create Sic1A10. These mutations eliminated Sic1 phosphorylation by Ime2 in vitro (Figure 4D).

To determine whether phosphorylation by Ime2 influenced the stability of Sic1 during sporulation, Sic1A10–HA was introduced into a sic1Δ/sic1Δ strain. Cells expressing Sic1A10–HA were able to proliferate, implying that this mutant protein could be destroyed during vegetative growth. When cells expressing Sic1A10–HA were induced to sporulate, the Sic1 protein was effectively degraded, although some of the protein persisted for up to 6 h into the sporulation time course (Figure 4E). Consistent with the destruction of Sic1, these cells were able to complete sporulation (results not shown).

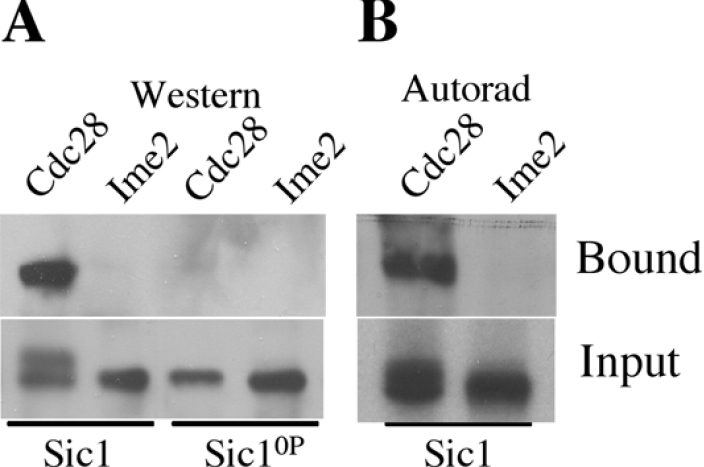

Phosphorylation by Ime2 is insufficient to promote Sic1 binding to SCF

To investigate whether phosphorylation of Sic1 by Ime2 was sufficient to allow it to bind SCFCdc4, Sic1 and Sic10P were extensively phosphorylated with either Cln2–Cdc28 or Ime2, and the phosphorylated Sic1 was mixed with Skp1–Cdc4 beads. Based on analysis by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis we estimate that 19% of the Cln2–Cdc28 treated Sic1 used in this experiment was maximally phosphorylated and 24% of the Ime2 treated Sic1 was maximally phosphorylated (results not shown). Phosphorylation of Sic1 by Cln2–Cdc28 leads to a mobility shift while phosphorylation by Ime2 does not (Figure 5A). A portion of the Sic1 that had been phosphorylated by Cln2–Cdc28 complexes was retained on the beads, whereas Sic1 phosphorylated by Ime2 was not retained (Figure 5A, upper panel). Additionally, Sic10P that had been treated with either Cln2–Cdc28 or Ime2 did not display binding to the Skp1–Cdc4 beads (Figure 5A, upper panel). We repeated this analysis using Sic1 labelled with [γ32P]- ATP to allow more sensitive detection (Figure 5B). Cln2–Cdc28 incorporated more 32P into Sic1 than did Ime2, therefore the Cln2–Cdc28 kinase reactions included only 50% as much [γ32P]ATP as did the Ime2 reactions, with the balance being made up by additionally unlabelled ATP. Sic1 phosphorylated by Cln2–Cdc28 was retained on the Skp1–Cdc4 beads (Figure 5B, upper panel). In contrast Sic1 that had been phosphorylated by Ime2 could not be detected in the bound fraction despite very long exposures.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation by Ime2 is insufficient to promote binding of Sic1 to Cdc4.

(A) 6his–Sic1 (lanes 1 and 2) and 6his–Sic10P (lanes 3 and 4) were phosphorylated with Ime2 or Cln2–Cdc28 complexes as indicated. The Sic1 that bound to Skp1–Cdc4 beads (upper panel) and 1/10th of the input sample (lower panel) were detected with α-Sic1 antibodies. (B) 6his–Sic1 phosphorylated by Ime2 or Cln2–Cdc28 in the presence of [γ32P]ATP was mixed with Skp1–Cdc4 complexes; the fraction of Sic1 bound to the beads (upper panel) and the unbound fraction (lower panel) were detected by autoradiography.

Sic1 is phosphorylated on multiple sites in vivo during sporulation and phosphorylation is reduced in ime2Δ cells

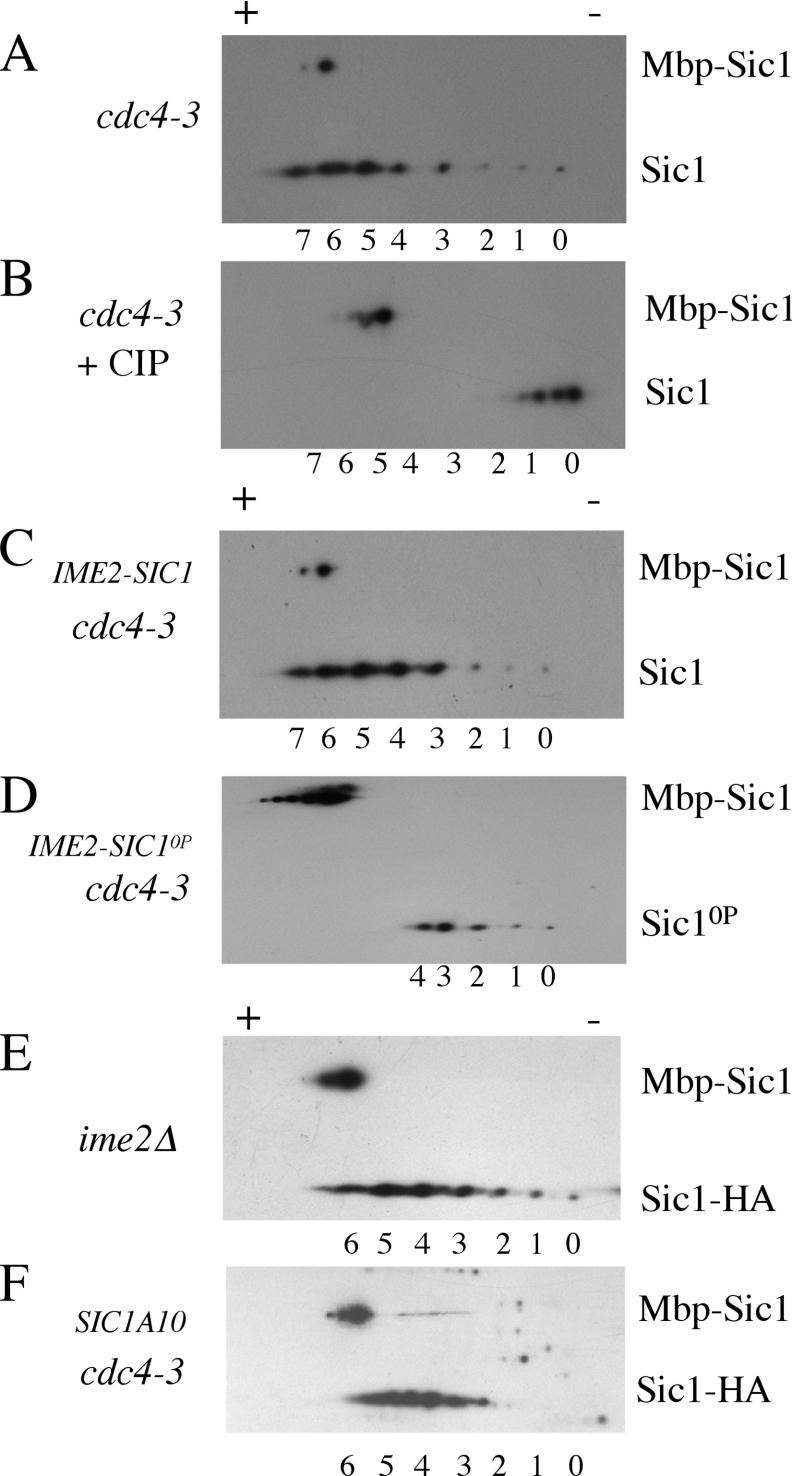

To determine the state of Sic1 modification in vivo during sporulation we prepared extracts from cdc4-3/cdc4-3 diploids that had been induced to sporulate at the non-permissive temperature of 37 °C. The phosphorylation state of Sic1HA in these extracts was analysed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting. A marker protein (Mbp–Sic1HA) was added to each sample to allow alignment of different gels. Sic1 isolated from sporulating cdc4-3/cdc4-3 cells minimally displayed eight different species (labelled 0–7, with 0 corresponding to the unmodified protein) that correspond to increasing numbers of phosphorylation events (Figure 6A). Treating Sic1 with CIP (calf intestinal phosphatase) prior to analysis by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis collapsed virtually all of the species into one or perhaps two forms, confirming that these spots represent phospho-species (Figure 6B). To determine whether the Sic1 Cdk sites were phosphorylated during sporulation we expressed Sic10P in sporulating cells. Sic10P displayed a significant reduction in the number of phospho-species that could be detected. While Sic1 existed in eight differentially migrating species (Figure 6C), Sic10P existed in five distinct species (Figure 6D). These data indicate that Sic1 is phosphorylated at Cdk sites during sporulation. Additionally, Sic1 is phosphorylated at multiple non-Cdk sites.

Figure 6. During sporulation the extent of Sic1 phosphorylation is reduced by mutation of Cdk sites and by deletion of Ime2.

Sic1 species separated on two-dimensional gels were detected by Western blotting. The differentially migrating Sic1 species are numbered 0–7. Recombinant Mbp–Sic1HA was added to the extracts as a marker. (A) Sic1 from cdc4-3/cdc4-3 diploids sporulating at the non-permissive temperature. (B) Half of the sample shown in (A) was treated with CIP. (C) Sic1HA and (D) Sic10P–HA were expressed under the regulation of an IME2 promoter during sporulation. (E) Sic1–HA phospho-species in ime2/ime2 diploids. (F) Sic1A10–HA expressed in cdc4-3/cdc4-3 diploids sporulating at the non-permissive temperature.

If Ime2 were responsible for the phosphorylation of Sic1 during sporulation we would anticipate that ime2/ime2 mutants would display a reduction in the number of Sic1 phospho-species. Sic1 isolated from sporulating ime2/ime2 mutants displayed a small but reproducible reduction in the extent of phosphorylation, indicated by the absence of the most phosphorylated form (Figure 6E). A comparison of these data also show that the less modified forms of Sic1 display more intense spots in ime2/ime2 mutants, consistent with a larger fraction of the Sic1 being less modified in ime2/ime2 mutant cells (compare the 0, 1 and 2 species of Sic1 in Figure 6A with Figure 6E). Consistent with this observation, Sic1A10, which lacks putative Ime2 phosphorylation sites, displayed a modest reduction in the extent of phospho-species that could be detected (Figure 6F). Interpretation of these data is however complicated by the fact that three of the sites mutated in Sic1A10 are also sites of Cdk phosphorylation. The reduction in phospho-Sic1 detected in the ime2/ime2 mutants is consistent with Ime2 phosphorylating Sic1 in vivo. However, the reduction is small, suggesting that Ime2 makes a minor contribution to Sic1 phosphorylation, implying that Ime2 is not the only kinase responsible for phosphorylation of Sic1 during sporulation.

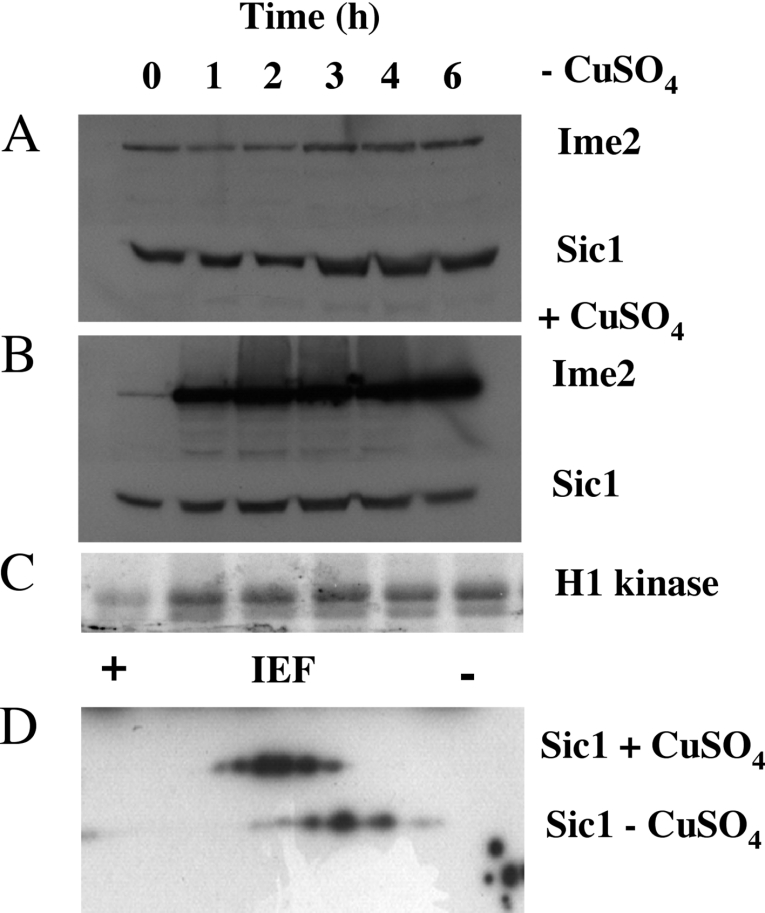

Expression of Ime2 in G1-phase cells is insufficient to trigger Sic1 destruction

Since phosphorylation of Sic1 by Ime2 was not sufficient to promote its interaction with Cdc4 in vitro, and since deletion of IME2 only modestly reduced the extent of Sic1 phosphorylation in vivo, we examined further the ability of Ime2 to induce Sic1 destruction. We reasoned that if Ime2 were capable of triggering Sic1 destruction then the expression of Ime2 in vegetative cells should allow Sic1 destruction in cells lacking G1 cyclins. To test this hypothesis, haploid cells were depleted of Cyclins, causing them to arrest in G1-phase with stabilized Sic1. These cells remained arrested in G1, and Sic1 remained stable for at least 6 h (Figure 7A). When the expression of Ime2 was induced, Ime2 protein and associated kinase activity could be detected (Figures 7B and 7C). However, despite the accumulation of Ime2 kinase, Sic1 remained stable and the cells remained arrested in G1-phase (Figure 7B). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis revealed that multiple species of Sic1 could be detected in the Cln-depleted cells, and induction of Ime2 caused a shift in the Sic1 species to the acidic end of the gel, consistent with an increase in phosphorylation (Figure 7D). Thus in these Cln-depleted cells Ime2 could be expressed, and its associated kinase activity led to the modification of Sic1, yet this was insufficient to trigger the destruction of Sic1.

Figure 7. Expression of Ime2 is insufficient to trigger the destruction of Sic1 in G1 arrested cells.

Sic1–HA and Ime2–MYC were monitored by Western blot in cells (A) without the induction of Ime2–MYC or (B) following the induction of Ime2–MYC. (C) Histone H1 kinase activity associated with the induced Ime2–MYC shown in (B). (D) Samples of Sic1–HA isolated from the experiments in (A) and (B) were subjected to two-dimensional electrophoresis and Sic1 species were detected by Western blot.

DISCUSSION

The regulated destruction of Sic1 is essential to promote timely initiation of DNA replication both during proliferation and during sporulation [19,20]. In the current study we have shown that SCFCdc4 is required to induce the destruction of Sic1 during sporulation. To date the only role assigned to Cdc4 in sporulation has been limited to the completion of recombination [33]. Both Sic1 and Cdc6 are SCFCdc4 substrates and both are effectively destroyed during sporulation, suggesting that SCFCdc4 may have similar substrate specificity during proliferation and sporulation [19,34].

In proliferating cells the ability of SCFCdc4 to bind Sic1 is dependent upon Sic1 being phosphorylated on at least six consensus Cdk phosphorylation sites, which correspond to CPD (Cdc4 Phospho-Degron) motifs [8]. Mutation of the Cdk sites to non-phosphorylatable residues stabilizes Sic1 and reduces the number of Sic1 phospho-species in vivo, implying that phosphorylation of the Cdk sites is required for Sic1 destruction during sporulation.

It has been proposed that phosphorylation of Sic1 by Ime2 promotes Sic1 destruction during sporulation [19]. Although Ime2 can phosphorylate Sic1 in vitro the phosphorylation of Sic1 by Ime2 does not allow Sic1 to bind Skp1–Cdc4 in vitro. Thus the Ime2 phosphorylated Sic1 would not be a good substrate for ubiquitination by SCFCdc4. Additionally, in ime2/ime2 mutants, ubiquitinated Sic1 can be detected and Sic1 is degraded, albeit with a delay relative to wild-type cells, indicating that Ime2 is not strictly required for the destruction of Sic1 in sporulating cells. Consistent with this idea, Ime2 expressed in G1 arrested haploid cells displayed kinase activity but was insufficient to promote Sic1 degradation. An explanation for this is that Ime2 may not phosphorylate Sic1 at a sufficient number of Cdk sites to promote its binding to SCFCdc4. Indeed IEF of Sic1 phosphorylated by Ime2 in vitro reveals a maximum of five species. It is possible that in vitro we were unable to achieve complete phosphorylation of Sic1 by Ime2, however under the same conditions we were able to phosphorylate Sic1 with Cln2–Cdc28 sufficiently to promote its interaction with Skp1–Cdc4. Additionally, deletion of IME2 resulted in a very modest reduction in the number of Sic1 phospho-species in vivo, suggesting that Ime2 is responsible for only a subset of Sic1 phosphorylation events in vivo.

We mapped the Sic1 residues that were phosphorylated by Ime2 in vitro and discovered that Ime2 phosphorylates Sic1 at a subset of Cdk consensus sites, but it also phosphorylates other sites. Four of the five sites we identified Thr45, Thr48, Ser146 and Thr173, all share the sequence motif PXS/TX. In addition, it has been reported that Ime2 phosphorylates Rfa2 at Ser27, which lies within a PGSG motif [35]. In addition to Sic1 and Rfa2, Ime2 has been reported to phosphorylate itself, Ime1, Cdh1 and Ndt80 [16,23,36,37]. However, the sites that Ime2 phosphorylates on the aforementioned proteins have not been elucidated. It has been previously proposed that Ime2 and Cdc28 perform interchangeable functions in promoting meiotic DNA replication [38]. Indeed we found that Ime2 does phosphorylate Sic1 at two sites where the PXS/T motif overlaps the Cdk consensus (Thr45, Thr173). The other sites phosphorylated by Ime2 do not conform to the CPD consensus motif and so are unlikely to contribute to the binding of Sic1 to Cdc4.

Although four of the five phosphorylation sites we identified conform to the consensus PXS/T we also identified Ser201, which falls within a casein kinase II motif, and Ser201 can be phosphorylated in vitro by CK2 [39]. Mutation of Ser201 to a non-phosphorylatable residue does not appear to increase the stability of Sic1 but has been reported to alter Sic1 activity [39]. Although we have determined that Ser201 is phosphorylated in vivo during sporulation we cannot at this time attribute this phosphorylation to Ime2.

Ime2 is clearly involved in Sic1 destabilization during sporulation, but the mechanism by which it acts is unclear. Ime2 could directly phosphorylate Sic1 and promote its interaction with Cdc4, much as Cln–Cdc28 does, during mitotic proliferation. Although our results show that phosphorylation of Sic1 by Ime2 alone is insufficient to promote Sic1 degradation, this does not categorically preclude Ime2 from acting as a ‘priming’ kinase, where Ime2 phosphorylation could promote the phosphorylation of Sic1 by another kinase. Similarly, Ime2 and another protein kinase might collaborate such that enough sites on Sic1 are phosphorylated to promote its interaction with SCFCdc4 and destruction via the proteosome.

A second possible role for Ime2 is that it might activate the SCF. Regulation of SCFCdc4 by phosphorylation has not been reported, and most evidence suggests that substrate modification is the limiting factor in SCFCdc4-mediated destruction of its targets. It is formally possible that the requirement for Ime2 to promote Sic1 destruction during sporulation is due to a necessity for Ime2 to activate SCFCdc4. We think this is unlikely however, since the SCFCdc4 substrate Cdc6 is effectively degraded in ime2/ime2 mutants that have been induced to sporulate [34]. The third possible mechanism by which Ime2 might promote Sic1 destruction during sporulation is through inducing the expression or the activity of another kinase that is required to phosphorylate Sic1. Ime2 kinase activity is essential to promote the full activation of early sporulation genes [17]. Thus a lack of Ime2 may reduce the activity of another kinase and so delay accumulation of the activity required for the elimination of Sic1 during sporulation. The identity of other protein kinases involved in Sic1 destruction remain to be revealed; however, Pho85, Hog1 and CK2 have been suggested to regulate Sic1 activity [39–41].

Ime2 plays multiple roles in both the early and middle stages of sporulation and has been proposed to trigger the destruction of Sic1 in sporulating cells; however, our data indicate that Ime2 alone is insufficient to promote Sic1 destruction. The key implication of this finding is that Sic1 stability is regulated by distinct mechanisms during sporulation and proliferation. This distinction may provide part of the basis upon which cells make a decision either to enter a mitotic division cycle or to initiate the sporulation programme.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Robinson for critical reading of this manuscript. We are also grateful to Michael Tyers (Bioinformatics and Functional Genomics, University of Toronto, Canada) for providing a Sic10P plasmid and Skp1–Cdc4 beads. This research was supported by an American Society for Cancer Research Postdoctoral Fellowship to J. W., and Operating Grants (MOP 62700) from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and (262070-03) from the Natural Sciences, Engineering and Research Council to D. S. and National Institute of Health Grant P41 RR11823-10 to J. Y.

References

- 1.Reed S. I. The role of p34 kinases in the G1 to S-phase transition. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1992;8:529–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.002525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasmyth K. Control of the yeast cell cycle by the Cdc28 protein kinase. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1993;5:166–179. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90099-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherr C., Roberts J. CDK Inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1 progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lew D. J., Weinert T., Pringle J. R. Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Pringle J. R., Broach J. R., Jones E. W., editors. Cell Cycle and Cell Biology, vol. 3. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 607–695. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwob E., Boehm T., Mendenhall M. D., Nasmyth K. The B-type cyclin kinase inhibitor p40SIC1 controls the G1/S transition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 1994;79:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma R., Feldman R. M., Deshaies R. J. Sic1 is ubiquitinated in vitro by a pathway that requires CDC4, CDC34 and cyclin/CDK activities. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:1427–1437. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma R., Annan S., Huddleston M. J., Carr S. A., Reynard G., Deshaies R. J. Phosphorylation of Sic1p by G1 Cdk required for its degradation and entry into S phase. Science. 1997;278:455–460. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nash P., Teng X., Orlicky S., Chen Q., Gentler F. B., Mendenhall M. D., Sicheri F., Pawson T., Tyers M. Multi-site phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor sets a threshold for the onset of DNA replication. Nature (London) 2001;414:514–521. doi: 10.1038/35107009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson A. D., Raghuraman M. K., Friedman K. L., Cross F. R., Brewer B. J., Fangman W. L. Clb5-dependent activation of late replication origins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:173–182. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartwell L. H., Weinert T. A. Checkpoints: Controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science. 1989;246:629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newport J. W., Kirschner M. W. Regulation of the cell cycle during early Xenopus development. Cell. 1984;37:741–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orr-Weaver T. L. Developmental modification of the Drosophila cell cycle. Trends Genet. 1994;10:321–327. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupiec M., Byers B., Esposito R. E., Mitchell A. P. Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Pringle J. R., Broach J. R., Jones E. W., editors. Cell Cycle and Cell Biology. Cold Spring Harbor NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 889–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartwell L. H. Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Cycle Bacteriol. Rev. 1974;38:164–198. doi: 10.1128/br.38.2.164-198.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colomina N., Gari E., Gallego C., Herrero E., Aldea M. G1 cyclins block the Ime1 pathway to make mitosis and meiosis incompatible in budding yeast. EMBO J. 1999;18:320–329. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kominami K., Sakata Y., Sakai M., Yamashita I. Protein kinase activity associated with the IME2 gene product, a meiotic inducer in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1993;57:1731–1735. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith H. E., Mitchell A. P. A transcriptional cascade governs entry into meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:2142–2152. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foiani M., Nadgar-Boger E., Capone R., Sagee S., Hashimshoni T., Kassir Y. A meiosis-specific protein kinase, Ime2, is required for the correct timing of DNA replication and for spore formation in yeast meiosis. Mol. Gen. Genetics. 1996;253:278–288. doi: 10.1007/s004380050323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dirick L., Goetsch L., Ammerer G., Byers B. Regulation of meiotic S-phase by Ime2 and a Clb5,6-associated kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1998;281:1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuart D., Wittenberg C. CLB5 and CLB6 are required for premeiotic DNA replication and activation of the meiotic S/M checkpoint. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2698–2710. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benjamin K. R., Zhang C., Shokat K. M., Herskowitz I. Control of landmark events in meiosis by the CDK Cdc28 and the meiosis-specific kinase Ime2. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1524–1539. doi: 10.1101/gad.1101503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose M. D., Winston F., Heiter P. A laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbour, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press; 1990. Methods in yeast genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sopko R., Raithatha S., Stuart D. Phosphorylation and maximal activity of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiosis-specific transcription factor Ndt80 is dependent on Ime2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7024–7040. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7024-7040.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willems A. R., Lanker S., Patton E. E., Craig K. L., Nason T. F., Mathias N., Kobayashi R., Wittenberg C., Tyers M. Cdc53 targets phosphorylated G1 cyclins for degradation by the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway. Cell. 1996;86:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raithatha S. A., Stuart D. T. Meiosis-specific regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae S-phase cyclin CLB5 is dependent on MluI cell cycle box (MCB) elements in its promoter but is independent of MCB-binding factor. Genetics. 2005;169:1329–1342. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sopko R., Stuart D. Purification and characterization of the DNA binding domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiosis-specific transcription factor Ndt80. Prot. Express. Purif. 2004;33:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacCoss M. J., McDonald W. H., Saraf A., Sadygov R., Clark J. M., Tasto J. J., Gould K. L., Wolters D., Washburn M., Weiss A., Clark J. I., Yates J. R., III Shotgun identification of protein modifications from protein complexes and lens tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:7900–7905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122231399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyle W. J., van der Geer P., Hunter T. Phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis by two dimensional separation on thin-layer cellulose plates. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:110–149. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pak J., Segall J. Regulation of the premiddle and middle phase of expression of the Ndt80 gene during sporulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6417–6429. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6417-6429.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orlicky S., Tang X., Willems A., Tyers M., Sicheri F. Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2003;112:243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chau V., Tobias J. W., Bachmir A., Marriott D., Ecker D. J., Gonda D. K., Varshavsky A. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short lived protein. Science. 1989;1989:1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogins R. R. W., Ellison K. S., Ellison M. J. Expression of a ubiquitin derivative that conjugates to proteins irreversibly produces phenotypes consistent with ubiquitin deficiendy. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:8807–8812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simchen G., Hirschberg J. Effects of the mitotic cell-cycle mutation cdc4 on yeast meiosis. Genetics. 1977;86:57–72. doi: 10.1093/genetics/86.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ofir Y., Sagee S., Guttmann-Raviv N., Pnueli L., Kassir Y. The role and regulation of the preRC component Cdc6 in the initiation of premeiotic DNA replication. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:2230–2242. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clifford D. M., Stark K. E., Gardner K. E., Hoffmann-Benning S., Brush G. S. Mechanistic insight into the Cdc28-related protein kinase Ime2 through analysis of replication protein A phosphorylation. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1826–1833. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.12.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guttmann-Raviv N., Martin S., Kassir Y. Ime2, a meiosis-specific kinase in yeast, is required for destabilization of its transcriptional activator Ime1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:2047–2056. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2047-2056.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolte M., Steigemann P., Braus G. H., Irniger S. Inhibition of APC-mediated proteolysis by the meiosis-specific protein kinase Ime2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:4385–4390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072385099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guttman-Raviv N., Boger-Nadjar E., Edri I., Kassir Y. Cdc28 and Ime2 possess redundant functions in promoting entry into premeiotic DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2001;159:1547–1558. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.4.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coccetti P., Rossi R. L., Sterieri F., Porro D., Russo G. L., Fonzo A., Magni F., Vanoni M., Alberghina L. Mutations of the CK2 phosphorylation site of Sic1 affect cell size and S-Cdk kinase activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:447–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishizawa M., Kawasumi M., Fujino M., Toh-e A. Phosphorylation of Sic1, a cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor, by Cdk including Pho85 is required for its prompt degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:2393–2405. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Escote X., Zapater M., Clotet J., Posas F. Hog1 mediates cell cycle arrest in G1 phase by the dual targeting of Sic1. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2004;6:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/ncb1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kane S. M., Roth R. Carbohydrate metabolism during ascospore development in yeast. J. Bacteriol. 1974;118:8–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.118.1.8-14.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stuart D., Wittenberg C. CLN3, not positive feedback, determines the timing of CLN2 transcription in cycling cells. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2780–2794. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]