Abstract

Background

Acute infectious conjunctivitis is a common disorder in primary care. Despite a lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of topical antibiotics for the treatment of acute infectious conjunctivitis, most patients presenting in primary care with the condition receive topical antibiotics. In the Netherlands, fusidic acid is most frequently prescribed.

Aim

To assess the effectiveness of fusidic acid gel compared to placebo for acute infectious conjunctivitis.

Design

Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial.

Setting

Twenty-five Dutch primary care centres.

Method

Adults presenting with a red eye and either (muco)purulent discharge or glued eyelid(s) were allocated to either one drop of fusidic acid gel 1% or placebo, four times daily during one week. The main outcome measure was the difference in recovery rates at 7 days. Secondary outcome measures were difference in bacterial eradication rates, a survival time analysis of the duration of symptoms, and the difference in recovery rates in culture-positive and culture-negative patients.

Results

One hundred and eighty-one patients were randomised and 163 patients were analysed. Forty-five of the 73 patients in the treatment and 53 of the 90 patients in the placebo group recovered (adjusted risk difference = 5.3% [95% confidence interval {CI} = −11 to 18]). There was no difference between the median duration of symptoms in the two groups. At baseline, the prevalence of a positive bacterial culture was 32% (58/181). The bacterial eradication rate was 76% in the treatment and 41% in the placebo group (risk difference = 35% [95% CI = 9.3 to 60.4]). In culture positive patients, the treatment effect tended to be strong (adjusted risk difference = 23% [95% CI = −6 to 42]).

Conclusion

At 7 days, cure rates in the fusidic acid gel and placebo group were similar, but the confidence interval was too wide to clearly demonstrate their equivalence. These findings do not support the current prescription practices of fusidic acid by GPs.

Keywords: antibacterial agents, conjunctivitis, family practice, randomised controlled trial, therapy

INTRODUCTION

In Western countries, acute infectious conjunctivitis is a common disorder with an incidence of 15 per 1000 patients per year in primary care.1–6 The GP diagnoses acute infectious conjunctivitis on the basis of signs and symptoms. In most cases, GPs do not feel able to differentiate between a bacterial and a non-bacterial cause. Therefore, in more than 80% of cases an ocular antibiotic is prescribed.2,7 In the Netherlands in 2001 more than 900 000 prescriptions for topical ocular antibiotics were issued and of these prescriptions, primary care physicians issued 85%.8 In England, 3.4 million community prescriptions for topical ocular antibiotics are issued each year.9 Although the practice guideline ‘The Red Eye’ of the Dutch College of General Practitioners recommends chloramphenicol as first choice ocular antibiotic, fusidic acid gel is most frequently prescribed for acute infectious conjunctivitis in the Netherlands.1,2 The reasons for this prescription policy are that fusidic acid gel needs to be administered less frequently than chloramphenicol, and appears to have no serious adverse effects.10 Comparative studies show that the effectiveness of fusidic acid gel in suspected acute bacterial conjunctivitis is similar to that of other ocular antibiotics.11–17 To our knowledge, no placebo controlled studies, investigating the effectiveness of topical ocular antibiotics for acute infectious conjunctivitis, have been carried out in a primary care setting.18 In contrast, a recently published systematic review on the effect of topical antibiotics for suspected acute bacterial conjunctivitis in secondary care settings showed that, compared to placebo, treatment with antibiotics was associated with significantly better rates of early (days 2–5) clinical remission (relative risk = 1.31 [95% confidence interval {CI} = 1.11 to 1.55]).19 The objective of our study was to assess the effectiveness of fusidic acid gel compared to placebo for acute infectious conjunctivitis in primary care patients.

METHOD

Settings and patients

Between October 1999 and December 2002, 41 GPs working in 25 care centres in the Amsterdam and Alkmaar region recruited patients for the trial. All eligible patients were referred for inclusion to nine designated ‘study’ GPs who worked in nine of the 25 centres. These GPs were instructed to include patients with a red eye and either (muco)purulent discharge or sticking of the eyelids. The exclusion criteria were age younger than 18 years, pre-existing symptoms longer than 7 days, acute loss of vision, wearing of contact lenses, systemic or local antibiotic use within the previous 2 weeks, ciliary redness, eye trauma, and a history of eye operation. All eligible patients were referred to one of the nine study GPs for enrolment in the study. Patients were recruited during office hours only. Before inclusion, a written informed consent was obtained. The patients were informed about the goal and duration of the study, the additional investigations (cultures), and about the choice of fusidic acid and the comparison to placebo. The patients were informed that, in case of infectious conjunctivitis, most patients receive a treatment with fusidic acid, and that there is no evidence that this treatment is beneficial. The patients were informed that possible harms due to withholding treatment were not expected. Subsequently, a standardised questionnaire and a standardised physical examination were completed by the study GP. The questionnaire contained questions about previous medical history (self-reported), duration of symptoms (days), self-medication and self-therapy, itching, burning sensation, foreign body sensation, and about the number of glued eyes in the morning (zero, one or two). The physical examination contained investigation of the degree of redness (peripheral, whole conjunctiva, or whole conjunctiva and pericorneal), the presence of peri-orbital oedema, the kind of discharge (watery, mucous, or purulent), and bilateral involvement (yes/no). Next, in a standardised way, one conjunctival sample of each eye was taken for a bacterial culture. For each patient, one eye was designated as the ‘study eye’. In case of two affected eyes, the one with worse signs and/or symptoms was the ‘study eye’. In case of two equally affected eyes, the first affected eye was the ‘study eye’. Next, the ‘study eye’ (that is, the patient) was allocated to either treatment with fusidic acid or placebo. In case of two affected eyes, the bilateral eye received the same treatment as the ‘study eye’.

How this fits in

Although ocular antibiotics, in particular fusidic acid, are usually prescribed, there is no publicised evidence on their effect in primary care patients with an acute infectious conjunctivitis. This study demonstrates that the effect of fusidic acid gel seems similar to placebo in primary care patients with an acute infectious conjunctivitis. GPs should be restrictive in blindly prescribing fusidic acid.

During a week, the patients kept a daily diary, containing six questions about the presence of symptoms in the study eye. These signs and symptoms were: discharge (yes/no); redness (yes/no); itching (yes/no); foreign body sensation (yes/no); glued eyelids in the morning (yes/no); and photophobia (yes/no).

Interventions

The patients were instructed to apply one drop of the study medication four times daily to the affected eye(s), starting on the day of inclusion. The GP demonstrated the first application. The patients received a written instruction for use. The study medication was either fusidic acid gel 10 mg/g (Fucithalmic®; Leo Pharmaceutical Products) or placebo gel (Vidisic® 2 mg/g: Tramedico). The patients were advised to use the study medication until 1 day after the signs and symptoms were recovered.

Seven days after inclusion the patients were asked to visit their GP for evaluation. Data about recovery, adverse effects, and ocular signs and symptoms were recorded using a standardised questionnaire. The questionnaire contained questions about itching, burning sensation, foreign body sensation, and about the number of glued eyes in the morning (zero, one or two). The physical examination contained investigation of the degree of redness (peripheral, whole conjunctiva, or whole conjunctiva and pericorneal), the presence of peri-orbital oedema, the kind of discharge (watery, mucous, or purulent), adverse effect, and the overall judgement of the GP if the study eye had recovered completely (yes/no). Again, two conjunctival samples were taken for a bacterial culture, one from each eye.

Any remaining study medication was weighed to get an impression of treatment adherence.

Objectives and outcomes

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of fusidic acid gel compared to placebo for recovery of acute infectious conjunctivitis in primary care patients.

The primary outcome measure was the difference in the proportions of patients recovered after 7 days of treatment. Recovery was defined as absence of any signs and symptoms, objectified by the GP, indicating conjunctivitis. Secondary outcome measures were the difference in bacterial eradication rates after 7 days, adverse effects, and a survival time analysis of the duration of symptoms. Finally, the extent to which the 7-day recovery rate in culture-positive patients differed from that in culture-negatives was studied.

Randomisation and blinding

The study medication was repacked into identical tubes by a local pharmacist under aseptic circumstances, according to the consecutive numbers on nine computer-generated randomisation lists, one for each GP. The tubes were then labelled with a code number. The GPs received the coded tubes, and handed out the tube with the first available code number to their consecutive patients. In this way, the patients were assigned in double blind fashion to either fusidic acid gel or placebo. The pharmacist was the only person in possession of the randomisation lists and was not involved in outcome measurement or data analysis. The code was broken only after the follow up had been completed and all data was entered into a database.

Microbiological procedures

Conjunctiva samples were taken by rolling a cotton swab (Laboratory Service Provider) over the conjunctiva of the lower fornix. The swabs were put in a transport-medium and sent to the investigating laboratory. On arrival, the swabs were inoculated onto blood agar enriched with 5% sheep blood, MacConkey agar, and chocolate agar. All media were house made using standard ingredients. After standard inoculation, the blood agar and MacConkey agar plates were incubated for a period of 48 hours at 35°C, whereas the chocolate agar plates were inoculated during the same period and temperature, but in 7% CO2 atmosphere. Cultures were further analysed daily according to the guidelines of the American Society for Microbiology.20 All pathogens were identified using routine standard biochemical procedures. The susceptibility of fusidic acid was assessed by determination of the minimal inhibitory concentration of this antibiotic using an Etest® (AB Biodisk) assay on Mueller–Hinton agar. Minimal inhibitory concentrations were read after incubation at 35°C for 24 hours according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Critical minimal inhibitory concentrations were used according to the Dutch National Standards.21

Statistics

The difference in recovery rates after 7 days between the study groups was analysed using a χ2 test (two-sided, unpaired). Logistic regression was used to adjust the (crude) treatment effect estimate for potential confounding effects due to post-randomisation imbalances (Table 1), and to study the extent to which the recovery rates between culture-positive and culture-negative patients differed. For easier interpretation, the odds ratios obtained from the regression analysis were converted into relative risks.22 These relative risks were converted into risk differences and numbers needed to treat using the recovery rate in the placebo group as the background risk. The 95% CIs of the numbers needed to treat (benefit) and numbers needed to treat (harm) are presented as recommended by Altman.23 An additional analysis, in which we assumed that all patients (18 in total) who were lost to follow up had not recovered at 7 days, was performed.

Table 1.

Characteristics at baseline (n = 181).

| Fusidic acid (n = 81) | Placebo (n = 100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 45.8 (14.7) | 41.0 (14.6) |

| Female | 42 (52) | 64 (64) |

| Median duration of symptoms before inclusion (days) | 3 (IQR = 2–4)a | 3 (IQR = 2–4) |

| History of infectious conjunctivitis | 20 (25) | 10 (10) |

| Self-treatmenta | 61 (75) | 73 (73) |

| Itch | 52 (64) | 59 (59) |

| Foreign body sensation | 40 (49) | 33 (33) |

| Burning sensation | 49 (61) | 60 (60) |

| One glued eye | 45 (56) | 62 (62) |

| Two glued eyes | 16 (20) | 20 (20) |

| Redness | ||

| peripheral | 33 (41) | 33 (33) |

| whole conjunctiva | 36 (44) | 44 (44) |

| conjunctival and pericorneal | 12 (15) | 22 (22) |

| unknown | 0 | 1(1) |

| Peri-orbital oedema | 29 (36) | 34 (34) |

| Discharge | ||

| none | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| watery | 24 (30) | 40 (40) |

| mucus | 36 (44) | 33 (33) |

| purulent | 19 (24) | 25 (25) |

| unknown | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Both eyes affected | 22 (27) | 19 (19) |

Values are numbers (%), unless stated otherwise.

cleaning with water. IQR = interquartile range.

The median duration of the combined symptoms (diary) in both groups was analysed using a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Of each patient, all recorded symptoms in the diary were combined in a new variable that was coded ‘1’ for patients who had become symptom free (all six symptoms in the diary absent) at day 1–7, and coded ‘0’ otherwise. In this way we were able to analyse the median duration of the combined symptoms (diary) in both groups.

The difference in bacterial eradication rates after 7 days was analysed using a χ2 test (two-sided). The distributions of the milligrams of study medication were compared between the study arms using the Mann-Whitney U test. A P-value of ≤0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference between the distributions of study medication use.

With a postulated recovery rate after 7 days of 95% in the intervention group and 80% in the placebo group, a difference in recovery of 15% was considered clinically relevant. With the type I and type II error rates at 0.05, and 0.20, respectively, the required sample size was 88 patients per group.

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 11.5.2).

RESULTS

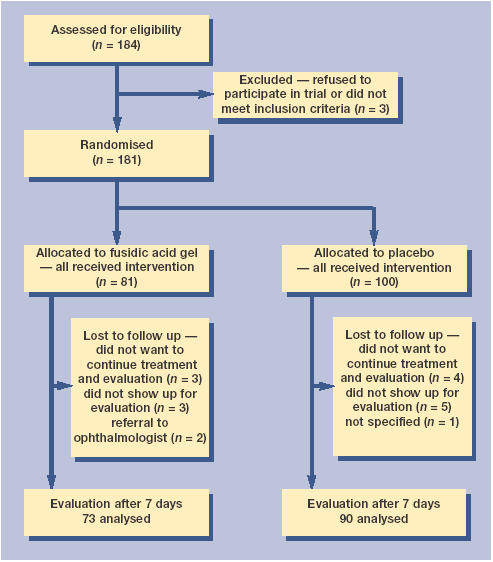

Forty-one GPs referred 184 patients to the GPs, of which 181 were randomised (Figure 1). With regard to baseline characteristics, the groups appeared comparable with possible exception of age, sex, history of infectious conjunctivitis, a foreign body sensation in the eye, and bilateral involvement (Table 1). In the fusidic acid and the placebo group 8 and 10 patients, respectively, were lost to follow up (Figure 1). Thus, 163 patients were analysed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients.

The median consumption of study medication was 1.51 g (interquartile range ([IQR] = 0.75–2.24) in the fusidic acid group, and 1.21 g (IQR = 0.87–1.69) in the placebo group (P = 0.303).

After 7 days, the proportion of recovered patients was 45/73 (62%) in the fusidic acid gel group and 53/90 (59%) in the placebo group (Table 2). Consequently, the probability of recovery was 2.8% greater in the fusidic acid group with a risk difference of 2.8% (95% CI = −13.5 to 18.6), the number needed to treat (NNT) (benefit) was 36.3 (95% CI = NNT [harm] 7.4 to ∞ to NNT [benefit] 5.4). Age was the only confounding factor and after adjustment the risk difference was 5.3% (95% CI = −11.0 to 18.0). The treatment effect seemed stronger in culture-positive patients (adjusted risk difference = 22.9% [95% CI = −6.0 to 42.0]) (Table 3). The additional analysis showed only a small effect on our results where the risk difference decreased from 5.3% (95% CI = −11.0 to 18.0) to 3.8% (95% CI = −11.0 to 18.0) (Table 4).

Table 2.

Numbers recovered at 1 week (n = 163).

| Fusidic acid n = 73 | Placebo n = 90 | Risk difference (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovered | 45 (62) | 53 (59) | 2.8 | −13.5 to 18.6 |

| Not recovered | 28(38) | 37 (41) | ||

| Adverse effects | 10(14) | 3 (3) | 10 | 1.6 to 19.1 |

Values are numbers (%), unless stated otherwise.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of effect of treatment by culture result.a

| Group | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | NNT (benefit) (95%CI)b | NNT (harm)a (95%CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 163 | 1.25 (0.64 to 2.39) | 18.97 (NNT[harm] 8.92 to∞ to NNT[benefit] 5.47) | – |

| Culture positive patients | 50c | 2.58 (0.79 to 8.42) | 4.36 (NNT[harm] 17.09 to∞ to NNT[benefit] 2.36) | – |

| Culture negative patients | 112c | 0.85 (0.37 to 1.86) | – | 25.25 (NNT[harm] 4.10 to∞ to NNT[benefit] 7.97) |

Corrected for age.

The odds ratios obtained from the regression analysis were converted into relative risks. The relative risks were converted into risk differences and numbers needed to treat using the clinical outcome rate in the placebo group as the background risk. The numbers needed to benefit and the numbers needed to harm and their 95% confidence intervals are presented as recommended by Altman.23

The culture result of one patient was missing. P-value of the interaction term is 0.122. NNT (benefit) = number needed to benefit. NNT (harm) = number needed to harm.

Table 4.

Additional analysis (patients who were lost to follow up (18 in total) were assumed not recovered at 7 days)

| Group | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | NNT (benefit) (95%CI)a | NNT (harm)a (95%CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 181 | 1.17 (0.64 to 2.13) | 25.85 (NNT[harm] 9.09 to∞ to NNT[benefit] 5.70) | – |

| Culture positive patients | 58b | 2.69 (0.91 to 7.98) | 4.15 (NNT[harm] 45.45 to∞ to NNT[benefit] 2.21) | – |

| Culture negative patients | 121b | 0.76 (0.36 to 1.59) | – | 14.78 (NNT[harm] 3.97 to∞ to NNT[benefit] 9.52) |

The odds ratios obtained from the regression analysis were converted into relative risks. The relative risks were converted into risk differences and numbers needed to treat using the clinical outcome rate in the placebo group as the background risk. The numbers needed to benefit and the numbers needed to harm and their 95% confidence intervals are presented as recommended by Altman.23

The culture results of two patients were missing. P-value of the interaction term is 0.05. NNT (benefit) = number needed to benefit. NNT (harm) = number needed to harm.

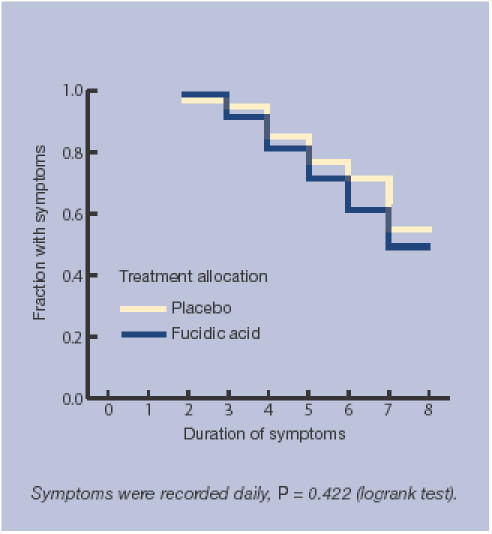

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves of symptoms (diary) did not differ significantly between the two groups (Figure 2; P = 0.422, logrank test). No patients became symptom-free within 2 days.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing times to disappearance of symptoms for the two groups.

Within the group of patients whose study eye had recovered at 1 week, 3.1% (3/98) of the non-study eyes showed signs and symptoms of conjunctivitis; 2.2% (1/45) in the fusidic acid group, and 3.8% (2/53) in the placebo group, respectively.

In both trial arms there were no clinically serious adverse outcomes.

At baseline, 58/181 (32%) patients were culture positive. The most prevalent cultured species was Streptococcus pneumoniae, accounting for 27/58 (47%) of the positive cultures. Overall, 38/58 (66%) cultures proved to be resistant to fusidic acid (Table 5). After 7 days, the bacterial eradication rates were 16/21 (76%) in the treatment group and 12/29 (41%) in the placebo group with a risk difference of 34.8% (95% CI = 9.3 to 60.4) and NNT (benefit) of 2.9 (95% CI = 1.7 to 10.8) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Cultured species at baseline and their susceptibility to fusidic acid (n = 181).

| Fucithalmic® n = 81 (%) | Placebo n = 100 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| No bacterial pathogen isolated | 55 (68) | 65 (65) |

| Bacterial pathogen isolated | 23(29) | 35 (35) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 9 (39) | 18 (51) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 7 (30) | 6 (17) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 3 (13) | 6 (17) |

| coagulase-negative Staphylococci | 3 (13) | 1 (3) |

| Other bacterium | 1 (4) | 4 (11) |

| Result of culture unknown | 3(3) | 0 |

| Fusidic acid resistance | ||

| Overall resistance | 14 (61) | 24 (69) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | ||

| sensitive (MIC ≤1)a | 0 | 0 |

| resistant (MIC >1) | 9 (100) | 15 (83) |

| unknown | 0 | 3 (17) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| sensitive (MIC ≤1) | 7 (100) | 6 (100) |

| resistant (MIC >1) | 0 | 0 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | ||

| sensitive (MIC ≤1) | 0 | 0 |

| resistant (MIC >1) | 3 (100) | 6 (100) |

| coagulase-negative Staphylococci | ||

| sensitive (MIC ≤1) | 2 (67) | 1 (100) |

| resistant (MIC >1) | 1 (33) | 0 |

| Other bacterium | ||

| sensitive (MIC ≤1) | 0 | 1 (25) |

| resistant (MIC >1) | 1 (100) | 3 (75) |

All MIC values are in mg/L, MIC = minimal inhibitory concentration.

Table 6.

Bacterial eradication after 1 week in culture-positive group (n = 50).a

| Fusidic acid n (%) | Placebo n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Culture positive | 21 | 29 |

| Successfully eradicated | 16 (76) | 12 (41) |

| Not eradicated | 5 | 17 |

At start, 50/163 analysable patients were found to be culture positive.

The proportion of patients that recorded adverse effects was 10/73 (14%) in the treatment group and 3/90 (3%) in the placebo group with a risk difference of 10.4% (95% CI = 1.6 to 19.1) and a NNT to treat of 9.7 (95%CI = 5.2 to 60.6). The most common adverse effect was a burning sensation after instillation of the study medication, with a prevalence of eight out of 10 in the treatment group and one in three in placebo group.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

This is the first study comparing fusidic acid gel to placebo for acute infectious conjunctivitis, and the first randomised controlled trial on this subject performed in a primary care setting. We found that the recovery rates after 7 days in the fusidic acid gel and placebo groups seemed essentially the same. However, our trial was too small to completely exclude clinically relevant treatment differences. The treatment effect in patients with a positive culture seemed higher, although CIs were fairly wide.

Strengths and limitations of the study

There were 81 patients in the fusidic acid group and 100 patients in the placebo group. This imbalance was caused by the so-called unrestricted randomisation procedure. With hindsight, the use of random permuted blocks of size two or four would have been preferable. However, it should be emphasised that this oversight affected the study's precision, not its (internal) validity.

In the fusidic acid gel and placebo group, 10% of the included participants were lost to follow up. The reasons for drop-out were essentially the same in both groups (Figure 1). As the additional analysis showed, any effect on the validity of the findings is unlikely.

The median consumption of study medication did not differ significantly between the two groups. Per protocol application (four drops per day during 1 week) implies 0.98 and 0.92 g of study medication in the fusidic acid and the placebo group, respectively. Since the median consumption in both groups is higher, it is unlikely that the difference in consumption of the study medication influenced the treatment effect.

Comparison with existing literature

Our findings seem to be at odds with a recently published systematic review on the effect of topical antibiotics for suspected acute bacterial conjunctivitis, although our study lacked power to show this conclusively.18 That review showed that, compared to placebo, treatment with antibiotics was associated with significantly better rates of early clinical remission (days 2–5) (relative risk = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.55). The difference in outcomes between these results and those of our study may be explained by the fact that our study was conducted in a primary care setting with potentially lower prevalence of positive cultures.

A meta-analysis by Sheikh et al showed that mainly in the first 3–5 days of the regimen, treatment with antibiotics was associated with significantly better rates of clinical remission.19 Since we found no significant difference in recovery at 7 days between the intervention and placebo group, it seems unlikely that a fusidic acid effect is present after 1 week. Therefore, we expect that a longer duration of follow up in our study would not have led to a better effect rate for fusidic acid gel compared to placebo.

It is interesting to note that 66% of the cultured species were resistant to fusidic acid. For the treatment of suspected acute bacterial conjunctivitis, it has been proven that fusidic acid gel is as effective as other ocular antibiotics, even when the resistance rate to fusidic acid was significantly higher.11–17 According to the Dutch standards, a minimal inhibitory concentration of 1 mg/L or higher indicates resistance to fusidic acid.21 However, the critical minimal inhibitory concentrations were estimated on the basis of measurements of antibiotic concentrations in serum, and not in tear fluid. A study on the pharmacokinetics of fusidic acid 1% viscous eye drops in healthy volunteers showed that the mean concentrations at 6 and 12 hours after instillation were 10 and 6 mg/L, respectively.10 Owing to the high concentrations of fusidic acid achieved in tear fluid, standardised susceptibility tests may not be appropriate to predict clinical effectiveness. This probably explains why the bacterial eradication rate in the fusidic acid gel group was much higher.

Implications for future research and clinical practice

In line with basic biology, the treatment effect in patients with a positive culture tended to be stronger than in culture negatives, although the P-value of the interaction term was not significant at the 5% level. Therefore, when future (primary care) research demonstrates a much greater effect of antibiotics in culture-positive patients, it seems attractive to develop an easy-to-use test to provide evidence for a bacterial cause, avoiding the delay that is currently associated with culturing. Alternatively, a validated diagnostic model based on currently available diagnostic indicators included in the signs and symptoms could be used.24

In conclusion, at 7 days, cure rates in both the fusidic acid gel and placebo group were similar, although the trial lacked power to demonstrate equivalence conclusively. These findings do not support the current prescription practices of fusidic acid by GPs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the GPs and patients in Heerhugowaard, Alkmaar, Nederhorst den Berg, and Amsterdam Noord for their participation in the trial. Especially, we would like to thank all the co-workers of pharmacy Van Zanten in Heerhugowaard and the laboratory of microbiology in Alkmaar for their cooperation.

Funding Body

Dutch College of General Practitioners (ZonMw) (4200.0006)

Ethics Committee

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam (MEC99/139)

Competing Interests

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Blom GH, Cleveringa JP, Louisse AC, et al. NHG Standaard Het rode oog [NHG Practice Guideline ‘The Red Eye’] Huisarts Wet. 1996;39:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okkes IM, Oskam SK, Lamberts H. Van klacht naar diagnose. Episodegegevens uit de huisartspraktijk. Bussum: Coutinho; 1998. [From complaint to diagnosis. Episodic data from general practice] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Werf GT, Smit RJA, Stewart RE, Meyboom-de Jong B. Spiegel op de huisarts: over registratie van ziekte, medicatie en verwijzing in de geautomatiseerde huisartspraktijk. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen; 1998. [Reflection on the general practitioner: about registration of illness, medication, and referrals in the computerised general practice] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dart JK. Eye disease at a community health centre. BMJ. 1986;293:1477–1480. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6560.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheldrick JH, Wilson AD, Vernon SA, et al. Management of ophthalmic disease in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:459–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonnell PJ. How do general practitioners manage eye disease in the community? Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:733–736. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.10.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everitt H, Little P. How do GPs diagnose and manage acute infective conjunctivitis? A GP survey. Fam Pract. 2002;19:658–660. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.6.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genees en hulpmiddelen Informatie Project. Annual report prescription data. Amstelveen, the Netherlands: College voor zorgverzekeringen; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health. Prescription cost analysis data. Leeds: Department of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorn P, Johansen S. Pharmacokinetic investigation of fusidic acid 1% viscous eye drops in healthy volunteers. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7:9–12. doi: 10.1177/112067219700700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson WB, Low DE, Dattani D, et al. Treatment of acute bacterial conjunctivitis: 1% fusidic acid viscous drops vs. 0.3% tobramycin drops. Can J Ophthalm. 2002;37:228–237. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(02)80114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malminiemi K, Kari O, Latvala ML, et al. Topical lomefloxacin twice daily compared with fusidic acid in acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1996;74:280–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1996.tb00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horven I. Acute conjunctivitis. A comparison of fusidic acid viscous eye drops and chloramphenicol. Acta Ophthalmol. 1993;71:165–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1993.tb04983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adenis JP, Arrata M, Gastaud P, et al. A multicenter randomized study of fusidic acid ophthalmic gel and rifamycine eyedrops in acute conjunctivitis. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1989;12:317–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dirdal M. Fucithalmic in acute conjunctivitis. Open, randomized comparison of fusidic acid, chloramphenicol and framycetin eye drops. Acta Ophthalmol. 1987;65:129–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1987.tb06989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hvidberg J. Fusidic acid in acute conjunctivitis. Single-blind, randomized comparison of fusidic acid and chloramphenicol viscous eye drops. Acta Ophthalmol. 1987;65:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1987.tb08489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Bijsterveld OP, el Batawi Y, Sobhi FS, et al. Fusidic acid in infections of the external eye. Infection. 1987;15:16–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01646112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rietveld RP, Van Weert HC, ter Riet G, et al. Diagnostic impact of signs and symptoms in acute infectious conjunctivitis: systematic literature search. BMJ. 2003;327:789. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikh A, Hurwitz B. Topical antibiotics for acute bacterial conjunctivitis: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:473–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall GS, Pezzlo M. Ocular cultures. In: Isenberg HD, editor. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook. Washington: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 1.19.1–1.20.44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouton RP, van Klingeren B. Standaardisatie van gevoeligheidsbepalingen, Verslag Werkgroep Richtlijnen Gevoeligheidsbepalingen. Bilthoven, the Netherlands: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieuhygiëne; 1981. [Standards for susceptibility testing. Dutch National Committee for Susceptibility testing] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309–1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rietveld RP, ter Riet G, Bindels PJ, et al. Predicting a bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis: cohort study on informativeness of combinations of signs and symptoms. BMJ. 2004;329:206–210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38128.631319.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]