Abstract

Objective:

Heller myotomy has been shown to be an effective primary treatment of achalasia. However, many physicians treating patients with achalasia continue to offer endoscopic therapies before recommending operative myotomy. Herein we report outcomes in 209 patients undergoing Heller myotomy with the majority (74%) undergoing myotomy as secondary treatment of achalasia.

Methods:

Data on all patients undergoing operative management of achalasia are collected prospectively. Over a 9-year period (1994–2003), 209 patients underwent Heller myotomy for achalasia. Of these, 154 had undergone either Botox injection and/or pneumatic dilation preoperatively. Preoperative, operative, and long-term outcome data were analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed with multiple χ2 and Mann-Whitney U analyses, as well as ANOVA.

Results:

Among the 209 patients undergoing Heller myotomy for achalasia, 154 received endoscopic therapy before being referred for surgery (100 dilation only, 33 Botox only, 21 both). The groups were matched for preoperative demographics and symptom scores for dysphagia, regurgitation, and chest pain. Intraoperative complications were more common in the endoscopically treated group with GI perforations being the most common complication (9.7% versus 3.6%). Postoperative complications, primarily severe dysphagia, and pulmonary complications were more common after endoscopic treatment (10.4% versus 5.4%). Failure of myotomy as defined by persistent or recurrent severe symptoms, or need for additionally therapy including redo myotomy or esophagectomy was higher in the endoscopically treated group (19.5% versus 10.1%).

Conclusion:

Use of preoperative endoscopic therapy remains common and has resulted in more intraoperative complications, primarily perforation, more postoperative complications, and a higher rate of failure than when no preoperative therapy was used. Endoscopic therapy for achalasia should not be used unless patients are not candidates for surgery.

The management of achalasia requires relief of the functional esophageal outlet obstruction caused by a nonrelaxing lower esophageal sphincter. Endoscopic therapies including pneumatic dilation and Botox injection at the lower esophageal sphincter are widely applied. The outstanding outcomes of surgical esophagogastric myotomy are compromised when endoscopic therapies are used prior to surgery.

Over the years, several studies have documented the excellent results of esophagogastric myotomy (Heller myotomy) for the management of achalasia.1–4 Despite this, endoscopic therapies such as pneumatic balloon rupture of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) or injection of Botulinum toxin (Botox) into the LES remain popular among gastroenterologists and are still widely offered and performed. Many surgeons have felt that the introduction of laparoscopic Heller myotomy and the benefits of an easier and less complicated recovery would result in a decline in the use of endoscopic therapies as first-line therapy for achalasia.5–9 In the past 12 years of performing laparoscopic Heller myotomy, this has not been our experience. Also, many surgical series have documented no difference in surgical outcomes when patients undergo endoscopic treatments prior to Heller myotomy.10–12 Again, anecdotally, this has not been our experience.

The aim of this study was to review our experience with Heller myotomy for primary achalasia, specifically assessing outcomes in those who had undergone endoscopic therapies prior to surgical intervention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The institution's Institutional Review Board approved this study. Data on all foregut patients undergoing surgery are collected prospectively and maintained in a computer database (Microsoft Access, Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA). Details on preoperative presentation and symptoms, results from objective testing (typically, barium swallow, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and esophageal motility), operative findings including surgeon documented operative complications (specifically esophageal or gastric perforation), and postoperative course were analyzed. The use of preoperative interventions (pneumatic dilation and Botox injection) and the number of interventions was specifically sought and recorded.

Preoperative and postoperative symptom assessment was performed 1 month after surgery and annually thereafter. Symptoms of heartburn, dysphagia, regurgitation, and chest pain were assessed using a 4-point scale (0 = none; 1 = mild to moderate; 2 = severe; 3 = intolerable).

Failure of surgical intervention was defined as persistence or recurrence of severe symptoms of dysphagia, regurgitation or chest pain (symptom scores of 2 or 3), need for endoscopic intervention(s), or repeat Heller myotomy or esophagectomy.

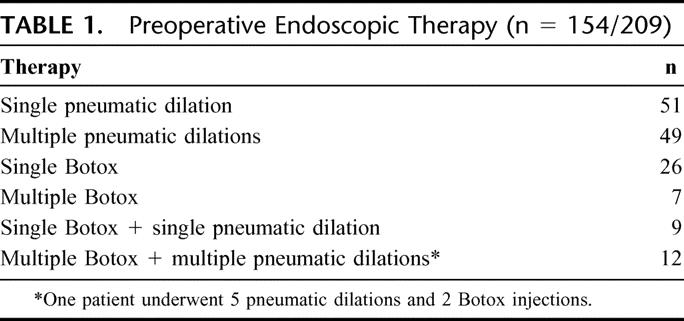

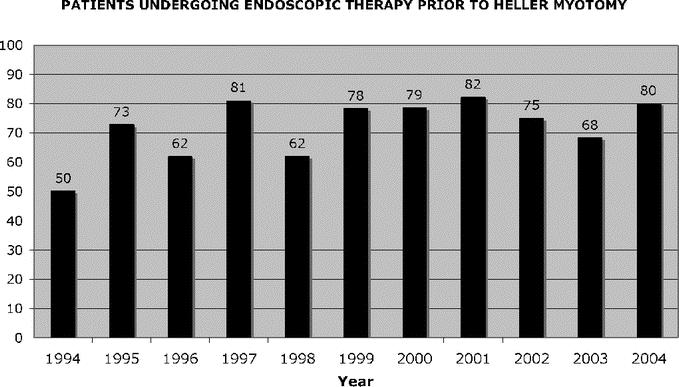

From 1994 through 2003, 209 patients underwent Heller myotomy for the management of primary achalasia. The diagnosis was established preoperatively by a barium swallow demonstrating the classic appearance of achalasia, an upper endoscopy confirming the absence of other pathology and an esophageal motility study documenting incomplete relaxation of the LES and severe derangement in esophageal peristalsis. In these 209 patients, 154 (74%) underwent either pneumatic balloon rupture of the LES (n = 100), Botox injection of the LES (n = 33), or both (n = 21) prior to Heller myotomy (Table 1). One half of the patients treated endoscopically underwent multiple or repeat procedures (n = 77), and in all cases the endoscopic therapy was rendered by a gastroenterologist prior to referral for surgical consultation and consideration of operative therapy. Since 1994, the number of patients referred who underwent preoperative endoscopic treatment has not changed (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1. Preoperative Endoscopic Therapy (n = 154/209)

FIGURE 1. Patients undergoing endoscopic therapy prior to Heller myotomy.

Operative Technique

The majority of cases were completed laparoscopically with only 4 patients undergoing an open procedure (98% laparoscopic). We have followed a standardized technique where the esophageal hiatus is fully dissected mobilizing the esophagus circumferentially and establishing at least 3 cm of intraabdominal esophagus and 6 cm of distal esophagus anteriorly for subsequent myotomy.13 The anterior and posterior vagus nerves are identified and left against the esophagus. A Penrose drain is secured around the distal esophagus and serves as a retractor to stabilize the esophagus during myotomy and facilitate the most proximal myotomy. Any epiphrenic fat pad is resected and the myotomy is completed by dividing the longitudinal and circular muscle fibers of the esophagus using a combination of monopolar electrocautery and muscle avulsion. The compliance of the esophageal mucosa is greater than that of the overlying muscle facilitating avulsion of the muscle immediately overlying the mucosa and minimizing the proximity of electrocautery to the mucosa.

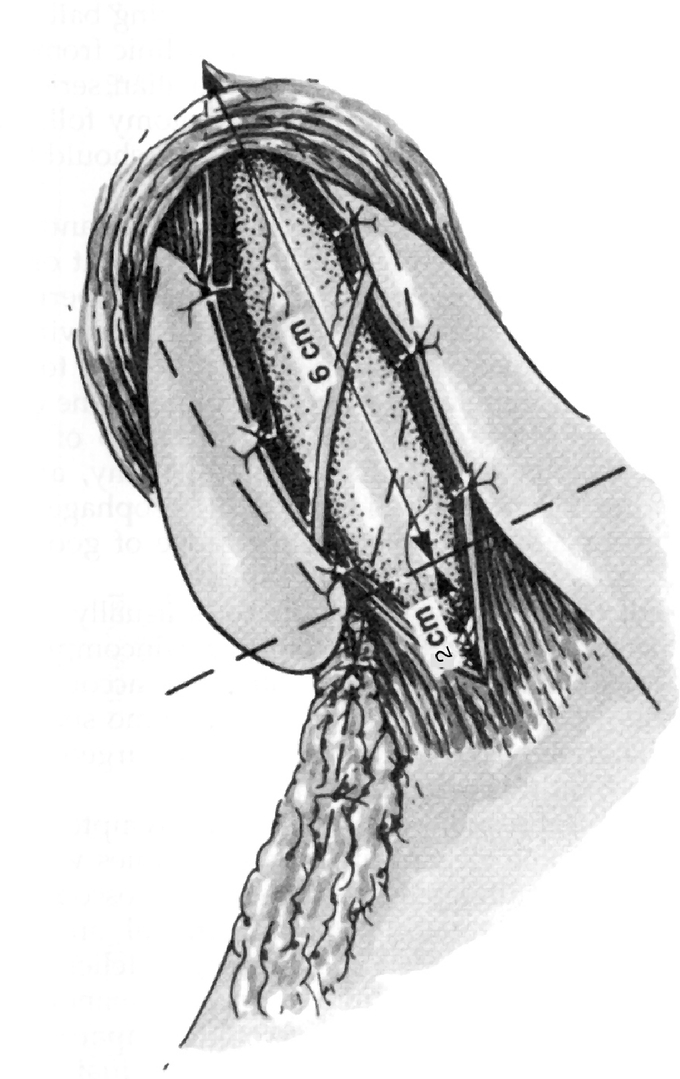

The myotomy spans at least 6 cm of distal esophagus and 2 cm onto the gastric cardia (Fig. 2). The sling fibers of the gastroesophageal junction are always visualized and divided. The anterior vagus nerve is variably oriented to either side of the myotomy or spanning the myotomy depending on its location.

FIGURE 2. Schematic of Heller myotomy with Toupet fundoplication.

The extent and completeness of the myotomy in addition to the integrity of the esophageal mucosa are checked by performing esophagoscopy to localize the squamocolumnar junction, assure a widely patent esophagogastric junction, and distend the distal esophagus with air to visualize a bulging mucosa without remaining muscular bands. The mucosal surface is then submerged underwater, looking for bubbles that would suggest a mucosal perforation.

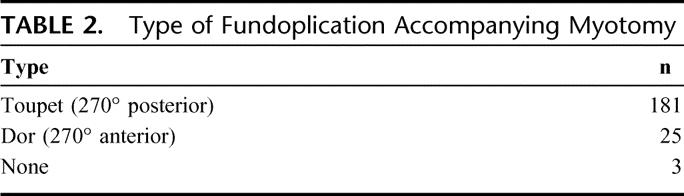

In all patients, an attempt is made to complete an antireflux procedure after the myotomy is complete. Our preferred antireflux procedure to accompany a Heller myotomy is a 270° posterior fundoplication (Toupet), suturing the cut edges of the myotomy to the completely mobilized gastric fundus (Fig. 2). In select patients, partial anterior fundoplication has been used (Dor) or no fundoplication at all (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Type of Fundoplication Accompanying Myotomy

Follow-Up

For the past 10 years, a full-time research nurse has been maintaining Emory's foregut database. In addition to collecting data from office visits, the research nurse also contacts patients every 2 to 3 years by phone or mail and has them complete a follow-up questionnaire. When a patient cannot be found through the contact information maintained in the database, an Internet search for the patient's contact information is conducted. This is a paid service and claims that if “an individual can not be found, they do not want to be found.”

With this follow-up strategy, follow-up information is available on 89% of the study group (187 of 209). However, as we have documented previously,14 over time the rate of follow-up decreases significantly. The average follow-up in these 209 patients is 20 months (range, 1–108 months). However, over 2 years follow-up information was only available in 32% of patients.

Statistics

The means of all continuous variables were compared by appropriate parametric or nonparametric tests including Mann-Whitney U analyses as well as analysis of variance. Categorical variables and proportions were compared with the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

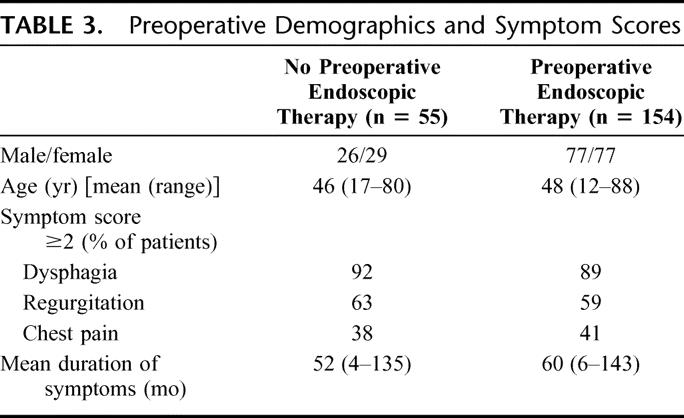

When comparing the outcomes of Heller myotomy for achalasia in those who received no preoperative endoscopic therapy (n = 55) with those who underwent preoperative endoscopic treatment (n = 154) both groups were matched for preoperative demographics and preoperative symptom scores for dysphagia, regurgitation and chest pain (Table 3). The mean duration of symptoms prior to undergoing myotomy was similar between groups.

TABLE 3. Preoperative Demographics and Symptom Scores

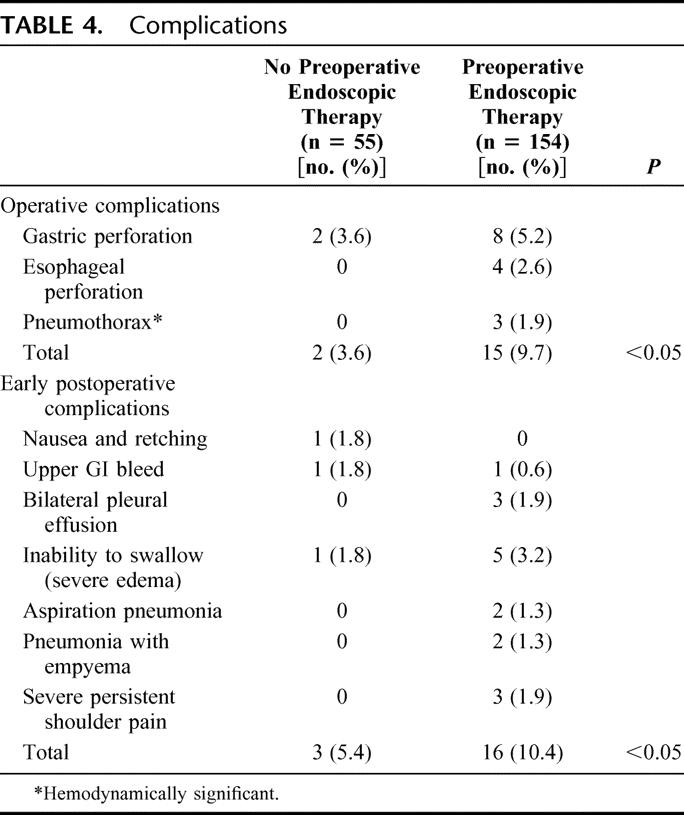

Patients who had undergone endoscopic therapy before Heller myotomy experienced more intraoperative and immediate postoperative complications (Table 4). The most common intraoperative complication in both groups was gastrointestinal perforation, and patients in both groups experienced gastric perforation. In contrast, only patients who had undergone prior endoscopic therapy experienced esophageal perforations. All perforations were identified intraoperatively and immediately repaired. Two patients with esophageal perforation were returned to the OR in the immediate postoperative period: one for persistent esophageal leakage and the other for thoracoscopic management of an empyema. Three patients in the endoscopic treatment group experienced a pneumothorax, and in each case there was an unusual mount of mediastinal scarring suggestive of inflammatory changes associated with prior treatments or even subclinical perforations.

TABLE 4. Complications

Early postoperative complications of inability to swallow secretions secondary to severe edema at the distal esophagus, and pulmonary complications were more common in those who had undergone prior endoscopic treatment. Two patients had aspiration pneumonia, 2 a pneumonia with empyema, and 3 with significant pleural effusions. Three patients experienced persistent and severe left shoulder pain, which prolonged the time to hospital discharge. This was thought to be related to diaphragmatic irritation secondary to scarring found in the mediastinum at the time of surgery.

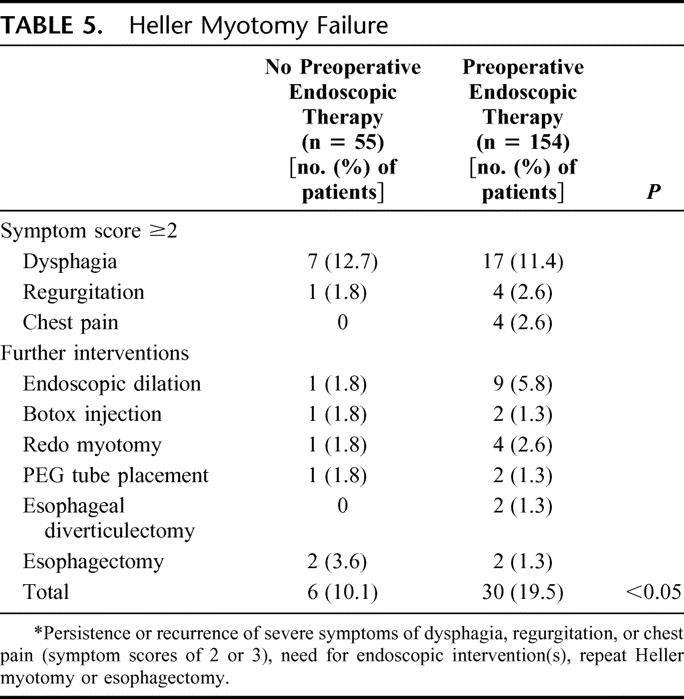

At an average follow-up of 21 months, the overall failure rate was 17.2% (36 of 209). While the frequency of unfavorable symptoms scores (severe or intolerable) for dysphagia and regurgitation were similar between groups, more patients who had undergone preoperative endoscopic therapy experienced failure than those without prior endoscopic treatment (6 of 55, 10.% versus 30 of 154, 19.5% respectively) (Table 5). Endoscopic dilation was the most common intervention necessary in managing failure, and at least half of the patients in the endoscopic therapy group required more than one dilation after myotomy. Four patients, 2 from each group, went on to esophagectomy to manage end-stage achalasia. In all 4 cases, the esophagus was significantly dilated prior to myotomy and postoperatively these patients failed to realize any improvement in swallowing. An esophageal diverticulectomy was necessary in 2 patients who developed symptomatic epiphrenic diverticula after myotomy. It is not clear what would have predisposed to this developing.

TABLE 5. Heller Myotomy Failure

DISCUSSION

The experience reported in this manuscript identifies several important issues as it relates to the management of achalasia. This includes the trend in the use of endoscopic management of achalasia prior to surgical referral, the impact of endoscopic therapies for achalasia on intra-and immediate postoperative complications, and its impact on long-term outcomes and in particular failure of surgical therapy to provide relief of preoperative symptoms.

Trends in the Use of Endoscopic Therapies

The foundation of the treatment of achalasia lies in relief of the functional esophageal outlet obstruction caused by the nonrelaxing LES and an aperistaltic esophagus. Whether endoscopic therapy with balloon rupture of the LES and/or injection of botulinum toxin, or surgical esophagogastric myotomy, the intent remains the same with each of these therapies. Historically, endoscopic therapies were selected as first-line therapy over surgery due to the morbidity associated with either the open thoracic or abdominal approach to myotomy. The introduction of thoracoscopic and laparoscopic myotomy has resulted in a significant decrease in the morbidity of a myotomy, and several large series have confirmed the excellent results with very low morbidity and mortality.5,8,10,15–17 Indeed, the author of a recent publication states, “Surgical myotomy, however, has regained primacy since the introduction of a minimally invasive laparoscopic approach in 1991.”6

This has not been our experience, and in this paper we detail the experience of a large, well-established, and recognized center that has been offering advanced laparoscopic techniques for foregut diseases since 1992. A full 10 years after the introduction of laparoscopic Heller myotomy, and 9 years after we started performing this procedure in high volumes, 82% of patients referred to our center had undergone endoscopic management of their achalasia prior to being referred (Fig. 1). Similarly striking is the persistence of this trend despite increasing evidence in the gastroenterology literature that endoscopic therapies are neither effective nor particularly durable.3,18–25 Perhaps surgeons are in part to blame for this persisting trend in that we have explicitly documented that prior endoscopic therapy does not negatively impact the outcomes of surgical myotomy.10–12

Impact of Endoscopic Therapies on Perioperative Outcomes

In that several authors have documented that endoscopic therapies for achalasia do not negatively impact on the perioperative outcomes of surgical myotomy, there would be little reason to not try an endoscopic approach prior to surgical referral. These surgical series have documented no impact on intraoperative complications, especially esophagogastric perforation and no significant increase in immediate postoperative complications. Anecdotally, this has not been our experience. In many of our patients who have had prior endoscopic therapies, there is a notable difference in the submucosal dissection plane, especially near the squamocolumnar junction. Often the plane is obliterated, and it is very difficult to confidently and easily dissect down onto the mucosa as can be accomplished in those who have not had prior therapies. We are very aggressive about the myotomy and feel that pursuit of a perforation rate of zero may lead to incomplete myotomy in many patients. In the patient who has had prior therapy, this philosophy may explain our perception that the dissection is more difficult as we will persist in our dissection to gain as complete a myotomy as possible. This philosophy may also explain the increase in perforation rate found in our patients.

The experience documented in this paper also confirms our impression that those who have had prior endoscopic therapies do experience an increase, not only in perforations but also in other intraoperative difficulties and postoperative complications. While most of the intraoperative complications were esophagogastric perforations that were found intraoperatively and repaired, several patients also experienced intraoperative problems likely related to significant mediastinal scarring. This scarring is best explained as a response to prior endoscopic therapies and even possible subclinical perforation from these therapies. Indeed, many patients report severe chest pain after pneumatic dilation and to a lesser extent after Botox injection, and despite a negative workup for perforation, this may indicate the damage that leads to the mediastinal scarring we encountered. One recent animal study looking at the impact of pneumatic dilation or Botox injection has shown significant mediastinal scarring 1 month after these interventions.26 Again, this certainly supports our clinical experience.

Several of the postoperative complications may be best explained as a consequence of a more difficult hiatal and mediastinal dissection in those who have had prior endoscopic therapies. Again, this has been our anecdotal experience, and complications of pleural effusions and persistent shoulder pain certainly would support this observation. The higher rate of inability to swallow and severe edema found on barium swallow may also be a consequence of a more difficult mediastinal dissection. This esophageal edema and difficulty swallowing may also explain the aspiration pneumonia experienced by several patients, although we do not have direct confirmation that other factors were not involved.

Failure After Heller Myotomy

In this series, the overall failure rate for surgical myotomy was 17%. This is comparable to that reported by others referenced in this manuscript. However, the likelihood of failure was significantly higher in patients who had undergone a prior endoscopic treatment, and the failure rate when no preoperative therapy was administered was 10%. Prior endoscopic therapy resulted in a near doubling of the failure after surgical myotomy. This has not been documented in any other series.

This finding may be all too convenient since it fits our impression after 12 years of caring for these patients. Admittedly, the findings here may in part be due to a too liberal definition of failure, especially when using symptom response when we have not considered the role GERD may play in the cause of these symptoms. We use an antireflux operation in nearly all patients undergoing Heller myotomy to prevent the GERD that may develop in up to 20% of patients who undergo myotomy alone. Even with an antireflux operation, some patients still develop symptomatic GERD, and a few present with erosive esophagitis. Using only dysphagia, regurgitation, and/or chest pain as an outcome measure and not specifically assessing for GERD may overestimate the failure rate since severe GERD can mimic some of the symptoms of myotomy failure. We do not consider GERD and its complications a failure of surgical myotomy. Indeed, we consider this a consequence of a successful myotomy; and since the majority of those who develop GERD after a myotomy and antireflux procedure can be treated with occasional antisecretory medication, we did not include this in our analysis.

Our follow-up in some patients is also short, and some authors have described continued resolution of dysphagia after longer periods of follow-up. Our short follow-up may have over estimated failure.

Finally, the higher incidence of failure, especially in the endoscopically treated group, raises the possibility of technical deficiencies with the myotomy itself. This is often most easily explained as a learning curve issue as one is gaining experience with the procedure. Early in one's experience, the previously treated patients may represent more challenging cases and therefore result in more complications and a higher rate of failure. While we are open to consider technical failure in the operating room as a contributor to our results, the 2 surgeons who performed the majority of these procedures have been performing advanced laparoscopy for a combined experience of over 20 years, including thousands of foregut procedures and these 209 myotomies, and as of this writing we have performed more than 260 Heller myotomies. The patients who had undergone endoscopic therapies were equally distributed throughout the 10-year experience, and these 2 features of this series would make a learning curve or technical issue in the operating room unlikely.

CONCLUSION

Despite published results documenting the superior results and safety with laparoscopic Heller myotomy over endoscopic therapies for achalasia, the majority of patients with achalasia continue to receive endoscopic therapies before referral for surgery. While many series in the surgical literature have documented an absence of a negative impact on outcomes when myotomy is performed after endoscopic therapy, this study is the first to demonstrate that the use of preoperative endoscopic therapy results in more intraoperative complications, more postoperative complications, and a higher rate of failure when compared with those who have undergone no preoperative therapy. Patients who are reasonable operative candidates should be referred for a surgical consultation before undergoing any treatment of their achalasia so that they can make an informed decision about the treatment they receive.

Discussions

Dr. Martin L. Dalton, Jr. (Macon, Georgia): Heller described the definitive surgical treatment of achalasia 91 years ago. The surgical procedure has progressed from laparotomy to thoracotomy to thoracoscopy and finally to the minimally invasive laparoscopic approach, which Dr. Smith so nicely described.

Paralleling the development of the surgical treatment of achalasia there has been numerous nonsurgical approaches to which Dr. Smith has already alluded. However, our gastroenterologists continue to be addicted to these nonsurgical approaches. By all objective criteria, the medical treatment of achalasia has been a dismal failure. Balloon dilation comes with a significant 3–5% esophageal rupture rate and less than optimal long-standing benefit.

The latest nonsurgical treatment is, of course, botulinum toxin, which is of short duration. Both dilation and Botox foster an attendant increase in morbidity and technical difficulty due to the obliteration of normal tissue planes at the time of myotomy.

With the emergence of the minimally invasive approach to achalasia, it would seem fitting that this should be offered to patients as the first line of therapy in all patients except those with excessive comorbidities that proscribe general anesthesia and even a minimally invasive surgical procedure. As obvious as this appears to us as surgeons, it is appalling that 74% of Dr. Smith's patients had previous Botox and/or pneumatic dilation prior to being referred for definitive treatment by surgery.

For all of these reasons, I endorse the conclusions reached by Dr. Smith and his associates. I have 2 questions for the authors.

Do you take any special precautions intraoperatively with patients referred for myotomy that had previous Botox or dilation other than not allowing the trainees to do these complicated procedures?

Were you able to determine the average number of encounters that patients had with gastroenterologists prior to them being referred for definitive surgical treatment?

Dr. C. Daniel Smith (Atlanta, Georgia): Special precautions? No, other than the discomfort we feel as we run into these scarred tissue planes and then we usually ask the trainee to step aside.

And, no, we haven't been able in this particular subgroup of patients to get at the total number of encounters. Our patients have memories sometimes of undergoing dilations every year for 5 and 6 years. But we rely largely on the patient's account, which has been unreliable.

Dr. Mark A. Talamini (San Diego, California): Many of us, when struggling to carefully dissect the esophageal tissue that you saw beautifully illustrated, in multiple previous procedures believed that the previous procedures must impact the outcome despite studies to the contrary. I do find a small degree of irony in the fact that a minimally invasive surgeon is arguing for the more invasive of the options. I would be interested in your comments on that. I also thank the authors for the opportunity to review the manuscript ahead of time. I do have a few questions.

In your series, were there particular reasons that some of the patients received Dor fundoplications or no fundoplications as opposed to your standard protocol?

Second, in those patients who failed, did any of them undergo re-exploration laparoscopically and a further myotomy? If so, what were those results?

Was there any further correlation between the number of preoperative medical procedures or between the length of time between the final procedure and the definitive operation in your series?

In your discussion, you speculate that some of your rare poor outcomes were likely due to the difficulty of the dissection due to the surrounding inflammation, perhaps from microperforations during medical procedures. Is it possible that those cases might have actually been better managed open rather than laparoscopically to potentially improve the outcomes?

Finally, taking the devil's advocate position and perhaps speaking for the gastroenterologists, many of them would argue that achalasia is a lifetime disease and that these procedures, while not perfect, are important in delaying surgery to the proper stage so that myotomy is not done at too early an age. Your conclusion obviously disagrees. But what in your mind would be the indications, if any, for dilatation or for Botox injections?

Dr. C. Daniel Smith (Atlanta, Georgia): I am not an advocate for more invasive approaches, I just don't like this less invasive approach. I think we need to continue to investigate and search for other ways, less invasive ways, that we might be able to treat achalasia.

What that may look like, I don't know today. But it is clear to me that the endoscopic approaches, while purportedly less invasive, do have long-term consequences. I think that is what we are seeing when we operate on these patients and find this mediastinal inflammation.

Dor versus Toupet versus none. I didn't show the data, but the vast majority of our patients have had a Toupet or a posterior fundoplication. A handful of our patients have had the Dor. And just a few, a scant few, I think 4 or 5 patients, have had no fundoplication.

So Toupet is our preferred approach, in part because we do this extensive posterior dissection and we basically disrupt the phrenoesophageal ligament posteriorly. And I think what the Toupet does, or the posterior fundoplication does, is it recreates that posterior angle that you basically disrupt by breaking the phrenoesophageal ligament and opening the crura widely. So that is our preference.

We have used the Dor in a few patients in whom we have had perforations or in whom we have suspected a perforation despite looking with our gastroscope. From time to time, if it has been a difficult dissection, we will take a Dor and place a Dor over the top of the mucosal surface in a protective sort of fashion.

We also were catalyzed to do a few Dors a few years ago because some of our colleagues around the country were purporting that the Dor was a superior antireflux procedure in this operation. We did a few of those, anecdotally didn't find we were particularly happy with it, and stopped using it as any kind of a routine.

The no fundoplication were in patients who had associated diverticula, epiphrenic diverticula, where we would bring the myotomy up to the neck of the diverticulum and a fundoplication would have led to a twist or distortion, because, as you know, these diverticula don't always expand anteriorly. If they come out laterally we will roll our myotomy to incorporate the diverticulum and it is very difficult to fashion a fundoplication that won't lead to some sort of twist or obstruction.

Failure and redos. We have done a few redos in a handful of patients. The outcome in that setting is about 50/50. Half the patients in whom we have done redos achieve or reachieve some symptomatic relief, half don't.

The correlation between time to diagnosis and treatment and our ultimate surgical treatment as this correlates to outcomes, we did not look at that. I do not have those data.

Let me talk lastly about endoscopy as a temporizer, because I think that is what you are talking about. As we head towards endoluminal therapies that have lower success but very few consequences—for example, for GERD, we now accept 60% to 70% success with an endoluminal therapy. We would never accept that for a surgical therapy.

But the key, in my opinion, to accepting a lower success rate is no consequence if it fails. And that is my issue here, in these patients we have a consequence. Anecdotally I felt this. These data now confirm that these endotherapies, while maybe reasonable for temporization, if it doubles your risk of failure, then a patient, even a young patient, needs to have that discussion and understand what these therapies may lead to long term.

Your last question had to do with open versus laparoscopic and should we have opened a few of these patients. In ten years of practice in this field now, I never get a better view and I never have a better chance at doing a very precise operation than I do when I am there with a laparoscope, magnification and inches away. So I convert rarely, and certainly not to improve my ability to do this fine dissection.

Dr. L. Michael Brunt (St. Louis, Missouri): Did you do any subgroup analysis to see if there was any difference in complication rates in patients who had a single endoscopic intervention versus multiple? You might predict in the latter group there would be more scarring and potentially a greater risk of intraoperative perforation or other complications.

Second, since there probably won't be a lot of gastroenterologists who read this paper, what are you doing to educate those in your community about earlier referral for a Heller myotomy?

Dr. C. Daniel Smith (Atlanta, Georgia): We have not done subgroups. That is a great idea, we should go back and take a look at that.

The educational process, I don't know what to say. It has been 10 years. We write. We speak. 80%—I was stunned, that 80% in 2004 were still undergoing these endotherapies. I think the message now needs to be that there is a consequence. This will show up in Annals of Surgery. I hope our gastroenterology colleagues will read that. But we will continue to try to let people know.

Dr. Robert V. Rege (Dallas, Texas): My question was along the same lines. I was also going to ask about the subgroup analysis. I am lucky enough in that physicians who treat patients with the balloon first at my institution use a single treatment with 30-millimeter balloon. But when you find someone who has either had multiple or has used 35 and 40 millimeter balloons, which, you know, have higher perforation rates, you find more inflammation and more difficulties. So did you look at balloon size as well as number of treatments in your patients?

Dr. C. Daniel Smith (Atlanta, Georgia): That is a great point. There are lots of variabilities in techniques with that dilation. No, we do not have those data. It is impossible in our setting for us to be able to go back and get that kind of detail.

Dr. William O. Richards (Nashville, Tennessee): I think it is interesting to look at the Vanderbilt results that we will present in the next paper showing that less than 50% of our patients underwent preoperative Botox or pneumatic dilation. It has been 8 years since the last pneumatic dilation occurred at Vanderbilt. So at least right now our current crop of gastroenterology trainees are no longer being trained in this technique and I suspect that we will see decreasing amounts of preoperative pneumatic dilation being done in the future.

But my question is, are these really pneumatic dilations or are they just endoscopic dilations that are being done? Do you have any data on the pre- and postoperative LES pressures in those patients that have undergone previous pneumatic dilation?

Dr. C. Daniel Smith (Atlanta, Georgia): Both you and Dr. Rege brought out a very good point. And that is, there is a lot of variability in how aggressive the gastroenterologists are today in these dilations. Sometimes they go down, they find it, they slip a bougie down or a little bit of a balloon and they call that a dilation. Regrettably I do not have that information in this patient population. It would be wonderful to be able to substratify on the aggressiveness of the dilation. I suspect we would just see these results amplified even further in those that are aggressively dilated.

We do have LES pressure. I do not have any correlative data that I can share with you today to see how that correlates.

Footnotes

Reprints: C. Daniel Smith, MD, FACS, Department of Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine, 1364 Clifton Road, NE (H124), Atlanta, GA 30322. E-mail: csmit27@emory.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonavina L, Nosadini A, Bardini R, et al. Primary treatment of esophageal achalasia: long-term results of myotomy and Dor fundoplication. Arch Surg. 1992;127:222–226; discussion 227. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ellis FH Jr, Crozier RE, Watkins E Jr. Operation for esophageal achalasia: results of esophagomyotomy without an antireflux operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;88:344–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okike N, Payne WS, Neufeld DM, et al. Esophagomyotomy versus forceful dilation for achalasia of the esophagus: results in 899 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1979;28:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinotti HW, Sakai P, Ishioka S. Cardiomyotomy and fundoplication for esophageal achalasia. Jpn J Surg. 1983;13:399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonatti H, Hinder RA, Klocker J, et al. Long-term results of laparoscopic Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication for the treatment of achalasia. Am J Surg. 2006;190:874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khajanchee YS, Kanneganti S, Leatherwood AE, et al. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy with Toupet fundoplication: outcomes predictors in 121 consecutive patients. Arch Surg. 2005;140:827–833; discussion 833–834. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Luketich JD, Fernando HC, Christie NA, et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagomyotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1909–1912; discussion 1912–1913. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Rosemurgy A, Villadolid D, Thometz D, et al. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy provides durable relief from achalasia and salvages failures after Botox or dilation. Ann Surg. 2005;241:725–733; discussion 733–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Sharp KW, Khaitan L, Scholz S, et al. 100 consecutive minimally invasive Heller myotomies: lessons learned. Ann Surg. 2002;235:631–638; discussion 638–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Deb S, Deschamps C, Allen MS, et al. Laparoscopic esophageal myotomy for achalasia: factors affecting functional results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1191–1194; discussion 1194–1195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Patti MG, Molena D, Fisichella PM, et al. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication for achalasia: analysis of successes and failures. Arch Surg. 2001;136:870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakita S, Bloomston M, Villadolid D, et al. Esophagotomy during laparoscopic Heller myotomy cannot be predicted by preoperative therapies and does not influence long-term outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, Waring JP. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and fundoplication for achalasia. Ann Surg. 1997;225:655–664; discussion 664–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Smith CD, McClusky DA, Rajad MA, et al. When fundoplication fails: redo? Ann Surg. 2005;241:861–869; discussion 869–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Frantzides CT, Moore RE, Carlson MA, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for achalasia: a 10-year experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrone JM, Frisella MM, Desai KM, et al. Results of laparoscopic Heller-Toupet operation for achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1565–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costantini M, Zaninotto G, Guirroli E, et al. The laparoscopic Heller-Dor operation remains an effective treatment for esophageal achalasia at a minimum 6-year follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allescher HD, Storr M, Seige M, et al. Treatment of achalasia: botulinum toxin injection vs. pneumatic balloon dilation: a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2001;33:1007–1017. [erratum appears in Endoscopy. 2004;36:185.] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Karamanolis G, Sgouros S, Karatzias G, et al. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, et al. Long-term results of pneumatic dilation for achalasia: a 15 years’ experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5701–5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinek J, Siroky M, Plottova Z, et al. Treatment of patients with achalasia with botulinum toxin: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16:204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suarez J, Mearin F, Boque R, et al. Laparoscopic myotomy vs endoscopic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vela MF, Richter JE, Wachsberger D, et al. Complexities of managing achalasia at a tertiary referral center: use of pneumatic dilatation, Heller myotomy, and botulinum toxin injection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1029–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West RL, Hirsch DP, Bartelsman JF, et al. Long term results of pneumatic dilation in achalasia followed for more than 5 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1346–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaninotto G, Annese V, Costantini M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia [see comment]. Ann Surg. 2004;239:364–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson WS, Willis GW, Smith JW. Evaluation of scar formation after botulinum toxin injection or forced balloon dilation to the lower esophageal sphincter. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:696–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]