Abstract

Objective:

To define the long-term characteristics, prognostic factors, and outcomes of patients undergoing selective splenorenal shunting procedures for portal hypertension-induced recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective evaluation of a prospectively collected data set.

Results:

From June 1971 through May 2005, 507 Warren-Zeppa shunts were performed at a single institution. Indications included: alcoholic cirrhosis, 52.6%; viral cirrhosis, 21.8%; cryptogenic cirrhosis, 8.4%; autoimmune cirrhosis, 5.8%; and other causes, 6.3%. Median survival was 81 months (5-year survival, 58.9%; 10-year survival, 34.4%; 20-year survival, 12.5%). patients with portal vein thrombosis and biliary cirrhosis demonstrated better survival than others (P = 0.03), while patients with alcoholic cirrhosis trended toward worse survival than those with nonalcoholic causes (P = 0.11). Multivariate analysis of preoperative risk factors found body hair loss (hazard ratio, 17.3; P > 0.005), preoperative encephalopathy (hazard ratio, 1.93; P > 0.003), diuretic use (hazard ratio, 1.43; P > 0.003), and age (hazard ratio, 1.02 per year of age; P > 0.051) were independent predictors of poor long-term survival. Multivariate analysis of operative factors demonstrated blood loss <500 mL was predictive of up to a 4-fold improved long-term survival (hazard ratio, 3.95; P < 0.013). Postoperative complications included: recurrent bleeding, 12%; ascites, 17.5%; and encephalopathy, 13.9%. Multivariate analysis of postoperative factors prospectively collected in 130 patients found that alcoholic recidivism (hazard ratio, 2.66; P > 0.001) was the only independent predictor of poor prognosis.

Conclusions:

The Warren-Zeppa shunt provides long-term survival and control of bleeding in most patients with portal hypertension. Excellent long-term survival can be obtained in properly selected patients with portal hypertension and relatively spared hepatic function.

The Warren-Zeppa shunt provides long-term survival and control of bleeding in most patients with portal hypertension. Based upon a 34-year follow-up of 507 patients we conclude excellent long-term survival can be obtained in properly selected patients with portal hypertension and relatively spared hepatic function.

The distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS) was conceptualized and developed at the University of Miami by Warren and Zeppa with the first patient series reported in 1967.1,2 Candidate patients for DSRS were initially those with life-threatening upper gastrointestinal bleeding but minimal or no ascites and intact prograde portal flow to the liver (hepatopetal flow).3 As with other shunting procedures, DSRS properly performed in appropriately selected patients results in a marked decrease in both esophagogastric varix size and episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB).4 Maintenance of portal pressure and hepatopetal flow remains the central theoretical advantage of DSRS versus less selective shunts.5,6 By preserving hepatopetal flow, the DSRS may delay and prevent the liver failure and encephalopathy associated with less selective shunts.5 Indeed, a number of studies have demonstrated that DSRS or other selective shunts are associated with decreased encephalopathy and improved 3- to 5-year survival relative to less selective shunting approaches, particularly in the setting of presinusoidal portal hypertension.5,7–10

Since the initial description of the DSRS, however, a number of alternative treatment modalities have been introduced, resulting in a marked decrease in the use of DSRS in the last 10 to 15 years.11–13 These alternative therapies include endoscopic sclerotherapy and banding, other shunting and devascularization procedures, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and liver transplantation. Endoscopic sclerotherapy is associated with improved 3- to 5-year survival relative to DSRS for patients who continue to drink alcohol and have immediate access to health care, but results in inferior outcomes relative to DSRS for patients who away from medical centers and for those who abstain from alcohol.9,14–16 Application of TIPS has become common because it can provide rapid control of bleeding and does not complicate subsequent liver transplantation, but it should be noted that prior DSRS is also not a contraindication to liver transplantation.17,18 TIPS is associated with high cost, dramatically increased rates of thrombosis (50% at approximately 2 years), and increased incidence of liver failure.16 Thus, patients who undergo TIPS frequently require revisions or additional TIPS placements.11,19,20 In contrast, it has been our observation that alcohol-abstinent patients with relatively preserved hepatic function21 and without continued hepatocellular destruction are particularly well served by DSRS alone and may never require additional procedures.11 Ongoing closed trials overseen by Henderson et al seek to determine quantitatively the benefit and survival of DSRS versus TIPS.22

The University of Miami experience is particularly well suited to determine the long-term benefits and complications arising from DSRS for the treatment of UGIB, not only because the procedures were largely performed by a select group of surgeons well versed in the nuances of the procedure, but also because it has the largest and oldest experience of DSRS, with follow-up exceeding 20 years. Prior studies examining 3- to 5-year follow-up are not able to reveal long-term results after DSRS. To better understand late outcomes associated with DSRS and how this technique should be integrated in the management of patients with UGIB from portal hypertension, we examined and present here our updated single-institution experience.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Cohort

The study was approved by the human subjects research committees at the University of Miami Hospital and Clinics, the Miami Veterans' Hospital, and Jackson Memorial Hospital. The splenorenal shunt registry of the University of Miami/Jackson Medical System prospectively collected data on all patients undergoing DSRS from 1971 to 1991. This registry was updated in the fall of 1992. From 1994 to May 2005, the names and medical record numbers of all patients undergoing DSRS were prospectively collected in a surgical operative series of the Dewitt Daughtry Department of Surgery. Patients undergoing DSRS during the years 1991 through 1993 were not prospectively collected and not included in this series. Overall, 507 cases of DSRS were identified.

Data Extraction

All identified cases from these 2 available data sets were pooled and updated using hospital and clinical records through May 2005. Medical records, including initial clinic notes, radiographic images, operative and pathology reports, and follow-up, were updated for each identified case when available. Survival was prospectively collected through the fall of 1992 and retrospectively updated for this series by reevaluation of the medical records and examination of the Social Security database.

Statistics

Overall survival time was calculated as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. SPSS version 13.0 was used for demographics and survival calculations. Kaplan-Meier was used to illustrate the survival rates and Cox regression was used for multivariate analysis of survival. The log rank test was applied to measure differences in survival.

RESULTS

Demographics

Overall, 507 patients who underwent DSRS were examined over a 34-year period from January 1971 to through May 2005. Median age of the cohort was 53 years. The age distribution is shown in Figure 1A. Numbers of DSRS procedures by year are shown in Figure 1B and demonstrate a marked reduction of patients undergoing DSRS in the 1990s onward, corresponding with the introduction of alternative therapies during this time period. Of note, cases performed in 1992 and 1993 were not prospectively collected and are not included in this analysis. Etiologies of the portal hypertension in patients undergoing DSRS are shown in Figure 1C. Overall, the majority of cases (52.6%) were performed for alcoholic cirrhosis (Table 1).

FIGURE 1. Patient demographics of the cohort. A, Age distribution of cases undergoing DSRS. B, Frequency distribution of cases by years 1971–2004. C, Etiology of portal hypertension.

TABLE 1. Patient Characteristics

Outcomes

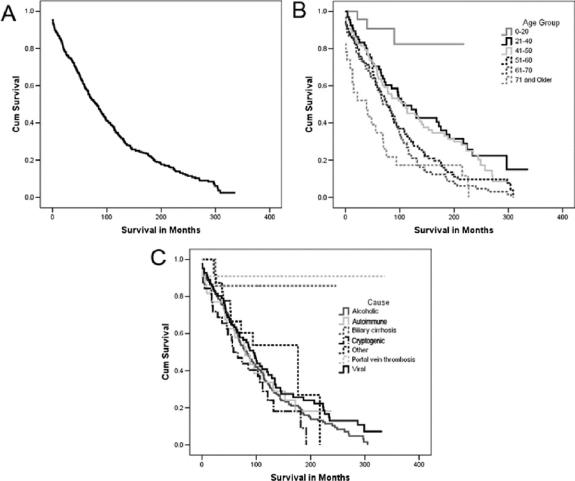

Overall survival for the cohort is shown graphically using the method of Kaplan-Meier in Figure 2A. Thirty-day mortality was 4.6%. Overall, median survival was 81 months and mean survival was 106 months. Five-, 10-, and 20-year survivals of 58.9%, 34.4%, and 15.9%, respectively, were obtained. Figure 2B presents survival by age group. Survival was significantly improved in younger patients. Figure 2C graphically presents the Kaplan-Meier survival curves by etiology of UGIB. A statistically improved survival in patients with portal vein thrombosis and biliary cirrhosis was observed relative to other etiologies. No other etiologies differed significantly from the overall survival of the cohort. Table 2 presents the median as well as 5-, 10-, and 20-year survivals for the overall cohort as well as by age group and etiology of UGIB.

FIGURE 2. Overall survival of the cohort. A, Overall survival of the cohort following DSRS. B, Survival by age decade. C, Survival by etiology of UGIB.

TABLE 2. Overall Survival by Age and Etiology

Preoperative Predictors of Survival

To define outcomes relative to current measures of liver function, we retrospectively reclassified our patients into both Child-Pugh and MELD scores where possible. Sufficient data were obtained to do this in 46% and 44% of the cohort respectively, predominantly in cases performed after 1980. A significantly improved survival in Child-Pugh A and B patients was observed relative to C patients. As well, a significantly improved survival was observed in patients with MELD scores less than 12.5. Of note, only 4 patients had MELD scores exceeding 20, with the highest MELD calculated at 37.2. All Child-Pugh and MELD scores were calculated based upon serum values obtained before surgery when the patients had mostly recovered from their acute bleed, and not during the resuscitation phase when there often was decompensation of the liver function. Survival by Child-Pugh and MELD is shown in Figure 3. Table 3 presents the median 5-, 10-, and 20-year survivals by Child-Pugh and MELD.

FIGURE 3. Survival by preoperative variables. A, Survival by Child-Pugh scores A, B, and C. Survival by MELD scores less than or greater than 12.5. C, Survival by the absence or presence of encephalopathy. D, Survival by presence or absence of preoperative ascites.

TABLE 3. Survival by Child-Pugh, MELD, and Other Preoperative Factors

Examination of other significant preoperative variables included a history of encephalopathy and presence of preoperative ascites. Absence of encephalopathy or ascites was associated with a significantly improved survival (Fig. 3; Table 3). Additional predictors of poor survival outcomes were the need for certain medications, including oral hypoglycemics, diuretics, and sedatives (P < 0.01).

Operative Factors Predictive of Long-term Survival

Most of DSRS used the classic procedure described by Warren, Zeppa and Foman,1,2 but variations were occasionally used because of anatomic difficulties encountered. Frequency for various reconstructions is shown in Figure 4A, with most of procedures performed being standard distal splenorenal shunts. Degree of pancreatic disconnection was difficult to determine as ligation of siphoning vessels was frequently performed as part of the surgery without specific reference to this aspect of the operation. No statistically significant difference was noted between various operative approaches for the method of splenorenal anastomosis. The method of anastomotic reconstruction was not associated with a decrease in overall survival (data not shown).

FIGURE 4. Surgical approach for DSRS and survival by intraoperative variables. A, Details of method of DSRS vascular reconstruction used. B, Survival by operative time, less than or greater than 6 hours. C, Survival by blood loss greater or less than 500 mL. D, Survival by intraoperative fluid greater or less than 4000 mL.

Operative factors associated with improved survival included an operative blood loss of less than 500 mL, an operative time of less than 6 hours, and an intraoperative requirement of less than 4 L of fluid. Figure 4 demonstrates the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each of these variables. This survival data are in Table 4 and include median 5-, 10-, and 20-year survivals.

TABLE 4. Survival by Intraoperative Parameters

Effects of Preoperative and Postoperative Ethanol Consumption

Numerous studies have identified ethanol consumption as one of the worst predictors of outcome following DSRS. Evidence of preoperative ethanol consumption was associated with a significantly decreased survival rate in our cohort. Examining the alcoholic UGIB subgroup demonstrated a significant reduction in survival among those who were consuming alcohol at the time of surgery (Fig. 5A). Of those patients who could be prospectively followed postsurgery, a markedly increased postoperative mortality rate was also observed in those patients who continued to drink (Fig. 5). Virtually no patient survived 10 years following DSRS if they continued with ethanol consumption. Table 5 presents these data and includes median 5-, 10-, and 20-year survival rates. Careful follow-up of patients was prospectively performed in a subset of 130 patients. Encephalopathy was observed in 13.9%, ascites in 17.5%, and rebleeding in 12% of patients with over 11 years of active follow-up.

FIGURE 5. Effects of alcohol consumption on outcome. A, Effect of preoperative ethanol consumption on DSRS survival. B, Effect of postoperative ethanol consumption on survival.

TABLE 5. Effects of Preoperative or Postoperative Alcohol Consumption

Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors

Cox regression proportional hazards analysis was performed on independent preoperative variables, operative variables, and postoperative variables. Significant variables are shown in Table 6. Backward stepwise multivariate analysis was also performed on all significant variables and confirmed the initial regression results.

TABLE 6. Significant Variables by Multivariate Analysis

DISCUSSION

This updated series represents the largest cohort with the longest follow-up of DSRS patients reported to date. Previous studies have suggested that the DSRS is associated with long-term (5–15 years) control of bleeding and is particularly effective in prolonging 3- to 5-year survival in those with presinusoidal hypertension and those who do not suffer from ongoing hepatocellular injury.11,23–25 Our series confirms these conclusions and documents extremely long-term survival in these patients, demonstrating 20-year survival exceeding 80% for patients with DSRS for UGIB from portal vein thrombosis or biliary cirrhosis. Dramatically improved survival of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis who underwent DSRS and abstained from alcohol following surgery was also observed, with a median survival approaching 10 years for the overall cohort. These data strongly support the initial hypothesis of Warren and Zeppa that maintenance of portal hepatic perfusion results in improved long-term hepatic function. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that DSRS may provide definitive therapy for portal hypertension-associated UGIB in properly selected patients. Conversely, for patients with persistent hepatocyte injury due to chronic active hepatitis or ongoing alcohol consumption, DSRS is associated with a dramatically worse prognosis.

Based upon this series, we suggest that patients with presinusoidal portal hypertension, preserved or stable hepatocellular function, and UGIB may be best served by a DSRS as 20-year survivals exceeding 85% are observed. As suggested by Henderson et al,26 liver transplantation in this subgroup should be reserved for DSRS failures. As well, given the large fraction of 10- and 20-year survivors among patients with stable liver disease in our cohort, we suggest that TIPS not be routinely used in these patients. We would propose that these patients should be considered for a DSRS or possibly other selective shunts such as the 8-mm H-graft portacaval shunts.27 Avoiding TIPS or other complete shunts in patients with stable disease must be stressed because complete shunts will result in hepatocellular failure over a period of a few years, eventuating in a liver transplantation or the patient's death.5,11 Many of our patients enjoyed prolonged survival, suggesting that the proper application of selective DSRS will prevent recurrent bleeding while avoiding liver failure, thereby potentially obviating the need for liver transplantation in a significant number of these patients, a concept previously put forth by Henderson et al.26 Based upon these data, we strongly support the treatment algorithm advocated by Wright and Rikkers for the management of portal hypertension.11 Patients with stable liver disease and an episode of UGIB who are selected for shunt surgery or fail sclerotherapy should undergo a selective shunting procedure. Based upon our experience, we suggest that the DSRS be chosen; alternatively, a selective 8-mm H-graft portacaval shunt, which also has good long-term results, may be considered.27

In contrast, we once again note markedly decreased outcomes in patients who underwent DSRS and suffered ongoing hepatic injury, particularly those who actively consumed alcohol postoperatively.28 No late survivors after 10 years were observed if alcohol use was ongoing. Similarly, reduced survival is observed in those patients with viral-induced cirrhosis, likely due to ongoing liver destruction from viral infection. In these patients, the long-term benefit of DSRS appears reduced and suggests a limited role for DSRS in these patients versus other modalities, especially transplantation.

Based upon our multivariate analysis, we conclude that improved overall survival may be observed in Child-Pugh A or B patients of younger age who do not have physical findings such as palmar erythema, body hair loss, or encephalopathy, which are indicative of advanced liver disease. Preoperative use of diuretics, diabetic medication, and sedatives was also a poor prognostic factor. Operative time and intraoperative bleeding were predictors of improved survival, suggesting that patients considered for this surgery should be referred to experts well practiced in the performance of DSRS. Of note, this series represents the work of a select group of surgeons well experienced in performing DSRS. It remains our unproven bias that the inexperienced surgeon could not and should not attempt to repeat the results observed in this series. This is supported by the dramatic improvement in outcome associated with a blood loss of less than 500 mL and an operative time shorter than 6 hours.

There are several limitations in the interpretation of this data set. First, the series is a retrospective examination of outcomes. Second, it is unclear if some patients might have been effectively treated with alternative therapeutic modalities. For example, endoscopic therapies were not routinely used in this cohort until the 1990s and sclerotherapy might have been sufficient for some of these patients. (Less than 20% of the patients in the cohort failed endoscopic sclerotherapy prior to undergoing DSRS therapy.) Finally, fewer than 20 patients in this cohort underwent liver transplantation, making it difficult to use this data set to examine the use of DSRS as a bridge to liver transplantation.

Future studies to better define the long-term survivors following DSRS are underway. First, the cohort with portal vein thrombosis or biliary cirrhosis will be further defined because these patients appear to have done particularly well following DSRS. In addition, we will examine outcomes for the cohort of older patients who were not transplant candidates to determine expected outcomes in this patient group. Finally, because the results obtained in this series are similar to the late follow-up reported by Rosemurgy et al,27 a comparison of outcomes between the small-diameter prosthetic H-graft portacaval shunt and DSRS is warranted.

This reevaluation of the DSRS experience of the University of Miami demonstrates excellent long-term survival in a difficult patient population. Use of selective shunting appears to be sufficient long-term therapy for a number of patients with portal hypertension-associated UGIB and stable liver disease. Increased application of the DSRS in the care of appropriate patients may allow a significant number of them to be definitively treated for their portal hypertension-associated bleeding while preserving liver function, and prevent some patients from requiring liver transplantation and lifelong immunosuppression.

Discussions

Dr. J. Michael Henderson (Cleveland, Ohio): This is indeed an historic paper, historic because it comes from the center of origin of this operation, and historic because the Southern Surgical Association has seen many presentations over the years of distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS). As the authors point out, this indeed is an operation that gives excellent control of variceal bleeding. I have a couple of comments.

When the DSRS was developed, decompressive surgical shunts were the treatment of choice. Other therapies weren't available. Over the past four decades, we have seen pharmacologic therapy, endoscopic therapy, TIPS, liver transplant all come into being, and that has changed things.

The biggest contribution in many ways of DSRS is that it has been the therapy against which all the other new therapies have been judged over those decades. As you all well remember, Dr. Warren insisted on randomized controlled trials. Dr. Zeppa was less of a fan of randomized trials but presented excellent data. Few operations have had the scrutiny that DSRS received in any randomized trials, comparing it to the “new” therapies. These trials initially compared it to total shunts, where bleeding control was equally good, and the encephalopathy rates were lower with DSRS. Then came the studies comparing it to endoscopic therapy still in the sclerotherapy era. These trials showed that DSRS was better at controlling bleeding, and there was a higher (but not statistically so) encephalopathy rate. The survival difference in the Emory trial was better with those who initially received sclerotherapy, while the Nebraska study had a survival advantage for DSRS. Those studies introduced the concept of surgical rescue. Sclerotherapy evolved into banding, and the combination of banding and pharmacologic therapy really changed the way patients with variceal bleeding are treated: this is now primary therapy preventing 80% of recurrent bleeding.

Finally, we have just completed a third round of randomized trials comparing DSRS to TIPS. This was an NIH-funded study, and the Miami group was one of the clinical centers. This trial compared these two “shunts” Child's A and B patients who had failed endoscopic therapy. The focus was on good-risk patients who were candidates for decompression. Should they be managed with TIPS or distal shunt?

The data from that trial will be published shortly. It shows an equivalent control of bleeding with TIPS and DSRA equivalent encephalopathy rates, equivalent survival, and equivalent occurrence of ascites. Reintervention for maintaining decompression is higher for TIPS.

So, DSRS has gone through these eras, and at the present time the issues really are: Who is going to do the shunts? Are there any shunters still out there? You and I love doing this operation; it is a great operation that works well. You have defined an excellent population, with normal liver function who are great candidates for DSRS.

Second question. You have the longest follow-up of anyone for DSRS, so as we control bleeding better, what are these patients dying from? We are seeing more patients dying of hepatoma now. Is this because the cirrhotic patients are alive for longer because their bleeding is controlled? Do you have data related to hepatoma as a cause of late mortality?

My final question relates to your re-bleeding rate, which is a little high at 12%. Most of the literature is around 5% to 6%. Is this a function of the longest follow-up? How much of that re-bleeding occurs late? There is a relentless development of collaterals toward the shunt from the high pressure portal vein across the stomach, and I suspect that some of your re-bleeding is late re-bleeding from these collaterals? A comment on your re-bleeding rate would be helpful.

Dr. Alan S. Livingstone (Miami, Florida): It is not quite as simple comparing TIPS to DSRS and just to look at the issue of re-bleeding and encephalopathy. I don't want to take away anything from what Mike is going to be presenting and publishing on it, but the other issue is the incidence of reintervention. It is quite clear, in the TIPS comparison to the distal splenorenal shunt, that if you follow the patients for even just a couple of years, virtually 83% of the patients have to be reintervened on and the costs become much more significant in the TIPS group than they are in the distal shunt group.

The issue about who does the shunt. At our institution, we still have a couple of people who are alive and well and able to do it. But it is very difficult to train the next generation of surgeons. It used to be in the early 1980s that you could train residents who could actually go out and do the operation. Dr. Hutson doesn't do them anymore. My other partner will do them if he is forced. I do an occasional one. And it happens to be one of my favorite operations. It is a great operation for teaching surgical technique, but it is going to be a real problem to train general surgeons because of low volume. It will probably end up being the transplanters who are used to managing cirrhotics and portal hypertension who will be doing the operation.

The cause of death in the various categories is interesting. With hepatomas, there is about a 10% incidence in both categories. The longer you follow hepatitis B and C patients, the more they develop tumors, particularly with hepatitis C. The older patients clearly go on to die of cardiovascular disease or progression of the liver disease. An interesting cohort in our patients who are alcoholics is trauma. I actually have a slide of a patient that was brought in with two large-bore knives in his torso, one of which was going right through the distal shunt. He did not do well.

The issue of bleeding. Dr. Henderson is, of course, correct that there is relentless development of collaterals over time, even with the complete pancreatic disconnect that was popularized in Atlanta. So some of these patients bleed late. But they are not usually massive bleeds unless the shunt thromboses.

Dr. Hiram C. Polk, JR. (Louisville, Kentucky): I would propose that, for me personally, this is the most fun paper on the program and probably the best. I think that it represents the most significant contribution to the literature that will come out of this meeting. What Dr. Livingstone has done in his 20-year follow-ups on a group of patients that are challenging is the sort of thing that helps surgical science becomes the basis of evidence-based surgery.

Dr. Hutson asked me to comment about several things. The best thing that ever happened to me in my life was going to work for Dr. Warren. When I went there, I was only the fourth person in the entire faculty. Our surgical suite was a cottage with a leak in the roof at the edge of the parking lot. In our opportunity to exchange ideas, Dr. Warren, Dr. Fomon, and Dr. Zeppa decided they would take the drunks and regional enteritis and I was given the burns and the melanomas. I have always thought that was an even trade.

The truth of Dr. Warren's interest in this is intimately related to the Southern. His first faculty appointment as assistant professor to Dr. Muller in Charlottesville led him to be interested in the treatment of portal hypertension and his hemodynamic studies. As I like to say, seven drunks in Charlottesville told us all the things we need to know about the hemodynamics of portal hypertension. He quickly realized, though, that patients that had direct shunts often died with an intolerable incidence of progressive liver failure, and he came to the conclusion that diversion of blood away from the liver is actually a terrible thing.

He compared that experience with what Dr. Womack had done at Chapel Hill when Dr. Zeppa was a resident there, in which they did devascularization operations and had frequent levels of re-bleed but no hepatic failure. Dr. Warren wondered and wondered whether there was a way to put this together, the best of both procedures.

One rainy afternoon he came in and tossed an issue of Surgical Gynecology & Obstetrics on my desk and said, “How can he do that?” Dr. Warren was a technical master and he was always in some ways in competition with Denton Cooley from their days in training, and Cooley had described a side-to-side splenorenal shunt. Dr. Warren said, “If he can do that, I can do it better.” I, of course, said, “Yes, sir.”

The truth was, this was the marriage of what he was looking for: a peripherally located shunt that would protect blood flow to the liver while decompressing the esophagogastric junction and its varices. So his intellectual origin was his thoughts about his own work, that liver failure rate with a direct shunt, the high re-bleed rate but no liver failure in patients who get devascularized, and then finally the idea that one could technically do, not a side-to-side shunt, but turn that distal splenic vein down and put it end to side was the way that worked.

It was a wonderful time to work with a wonderful person. This is more than a 20-year follow-up; it is a lifetime follow-up of a work from a single institution, and, Dr. Livingstone, you ought to be as proud of this as anything you have done. First class!

Dr. R. Neal Garrison (Louisville, Kentucky): I rise to give honor to Dr. Warren and Dr. Zeppa. Both men influenced my career in surgery.

I had the privilege of scrubbing on the first case that Dr. Warren did at Emory Hospital as a senior medical student. I was always remembered by him as Medical Student 4 Garrison even when I was a senior resident.

Dr. Zeppa influenced my career because he discussed the first paper that I ever presented here at the Southern Surgical Association. And in that case, he took me aside before and instructed me on the answers that I was to give to his questions.

While their names will always be attached to this procedure of distal splenorenal shunt, my hope is they will always be remembered as exceptional teachers and mentors to a generation of surgeons.

Dr. Mellick T. Sykes (San Antonio, Texas): My question is technical. I was trained doing porta-caval shunts but was chased from the portal area by the advent of liver transplantation with the request that the portal vein area be left virgin for subsequent transplantation. My understanding was that a key component of the selective distal splenorenal shunt dissection of the portal vein to identify and ligate coronary veins. Has this desire to protect the virginity of the porta hepatitis changed your approach to this aspect of the operation over the years?

Dr. Alan S. Livingstone (Miami, Florida): No, sir. The distal splenorenal shunt does not really intrude upon that space. It is done from behind the stomach and underneath the pancreas, and it doesn't really make the liver transplant much more difficult. The issue of how to handle the shunt or whether you do a splenectomy is a separate issue. But the operation itself, the distal shunt, does not usually interfere with the performance of the liver transplant.

Dr. Lawrence Lottenberg (Gainesville, Florida): For those of you that did not have the experience of being trained by these gentlemen who are in the room and by Dr. Zeppa, I rise to congratulate the people that brought this history forward.

As a fourth-year medical student, I won the John Fomon award. That plaque still sits on my wall. And as a chief resident in 1980, as Dr. Livingstone pointed out in his graphic, you can see the number of these operations we did. My comment is that there is not more of an elegant operation that I have ever done.

I also rise to tell you that this operation can be done in private practice. I did over a dozen of these myself in private practice. Unfortunately, as Dr. Livingstone points out, there aren't a lot of people that know how to do this operation well, and I certainly am honored and impressed to be part of this experience.

Footnotes

Reprints: Alan S. Livingstone, MD, FACS, 3550 Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center (310T), 1475 NW 12th Ave., Miami, FL 33136. E-mail: alivings@med.miami.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warren WD, Zeppa R, Fomon JJ. Selective trans-splenic decompression of gastroesophageal varices by distal splenorenal shunt. Ann Surg. 1967;166:437–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren WD, Fomon JJ, Zeppa R. Further evaluation of selective decompression of varices by distal splenorenal shunt. Ann Surg. 1969;169:652–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeppa R, Warren WD. The distal splenorenal shunt. Am J Surg. 1971;122:300–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutson DG, Pereiras R, Zeppa R, et al. The fate of esophageal varices following selective distal splenorenal shunt. Ann Surg. 1976;183:496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rikkers LF. Is the distal splenorenal shunt better? Hepatology. 1988;8:1705–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren WD, Salam AA, Hutson D, et al. Selective distal splenorenal shunt: technique and results of operation. Arch Surg. 1974;108:306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva LC, Strauss E, Gayotto LC, et al. A randomized trial for the study of the elective surgical treatment of portal hypertension in mansonic schistosomiasis. Ann Surg. 1986;204:148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spina GP, Henderson JM, Rikkers LF, et al. Distal spleno-renal shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy in the prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis of 4 randomized clinical trials. J Hepatol. 1992;16:338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson JM, Kutner MH, Millikan WJ Jr, et al. Endoscopic variceal sclerosis compared with distal splenorenal shunt to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosemurgy AS, Zervos EE, Goode SE, et al. Differential effects on portal and effective hepatic blood flow: a comparison between transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunt and small-diameter H-graft portacaval shunt. Ann Surg. 1997;225:601–607; discussion 607–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wright AS, Rikkers LF. Current management of portal hypertension. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:992–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosch J, Garcia-Pagan JC. Complications of cirrhosis: I. Portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2000;32(suppl 1):141–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharara AI, Rockey DC. Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rikkers LF, Jin G, Burnett DA, et al. Shunt surgery versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for variceal hemorrhage: late results of a randomized trial. Am J Surg. 1993;165:27–32; discussion 32–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Wong LL, Lorenzo C, Limm WM, et al. Splenorenal shunt: an ideal procedure in the Pacific. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1125–1129, discussion 1130. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.D'Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: a meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995;22:332–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato T, Levi DM, DeFaria W, et al. Liver transplantation with renoportal anastomosis after distal splenorenal shunt. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1401–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato T, Levi DM, DeFaria W, et al. A new approach to portal vein reconstruction in liver transplantation in patients with distal splenorenal shunts. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;30:612–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, et al. The natural history of portal hypertension after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koniaris LG, McKillop IH, Schwartz SI, et al. Liver regeneration. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:634–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson JM, Boyer TM, Kutner MH. DSRS vs TIPS for refractory variceal bleeding: a prospective randomized trial. Hepatology. 2004;40:725A. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson JM. Role of distal splenorenal shunt for long-term management of variceal bleeding. World J Surg. 1994;18:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeppa R, Hutson DG Sr, Levi JU, et al. Factors influencing survival after distal splenorenal shunt. World J Surg. 1984;8:733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeppa R, Lee PA, Hutson DG Sr, et al. Portal hypertension: a fifteen year perspective. Am J Surg. 1988;155:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson JM, Gilmore GT, Hooks MA, et al. Selective shunt in the management of variceal bleeding in the era of liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1992;216:248–254; discussion 254–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Rosemurgy AS, Bloomston M, Clark WC, et al. H-graft portacaval shunts versus TIPS: ten-year follow-up of a randomized trial with comparison to predicted survivals. Ann Surg. 2005;241:238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeppa R, Hensley GT, Levi JU, et al. The comparative survivals of alcoholics versus nonalcoholics after distal splenorenal shunt. Ann Surg. 1978;187:510–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]