Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of pancreatic resection in pancreatic endocrine neoplasias (PENs) in patients affected by multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) syndrome.

Background:

Since these tumors often show an indolent course, the role of diagnostic procedures and type of surgical approach are controversial. Experience with new diagnostic approaches and more aggressive surgery is still limited.

Methods:

Sixteen MEN1 patients were referred to our Surgical Unit (1992–2003) and were operated on for the indications of hypergastrinism, hypoglycemia, and/or pancreatic endocrine neoplasias larger than 1 cm. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) was present in 13 patients, 2 of whom experienced a recurrence after previous surgery. Preoperative tumor localization was carried out using ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SSRS), or selective arterial secretin injection (SASI). Rapid intraoperative gastrin measurement (IGM) was carried out in 8 patients, and 1 patient also underwent an intraoperative secretin provocative test.

Results:

Either pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) or total pancreatectomy (TP) or distal pancreatectomy was performed. There was no postoperative mortality; 37% complications included pancreatic (27%) and biliary (6%) fistulas, abdominal collection (6%), and acute pancreatitis (6%). EUS and SSRS were the most sensitive preoperative imaging techniques. At follow-up, 10 of 13 hypergastrinemic patients (77%) are currently eugastrinemic with negative secretin provocative test, while 3 are showing a recurrence of the disease. All patients affected by insulinoma were cured.

Conclusions:

MEN1 tumors should be considered surgically curable diseases. IGM may be of value in the assessment of surgical cure. Our experience suggests that PD is superior to less radical surgical approaches in providing cure with limited morbidity in MEN1 gastrinomas and pancreatic neoplasias.

To evaluate the results of pancreatic resection in pancreatic endocrine neoplasias in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, 16 patients were operated on for hypergastrinism, hypoglycemia, and/or pancreatic endocrine tumors greater than 1 cm. Our results indicate pancreaticoduodenectomy as the appropriate surgical approach in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 gastrinomas and pancreatic neoplasias.

The prevalence of pancreatic endocrine neoplasias (PENs) in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1)-affected individuals varies from 30% to 75% in different clinical series.1–3 Pathologic features consist of multiple nodular lesions of different endocrine cells ranging from microadenomas to macroadenomas and from benign to invasive and metastatic carcinomas. The nonfunctioning PENs are the most frequent lesions (80%–100%), while gastrinomas and insulinomas are the most common functional lesions occurring in 60% to 80% of affected patients.4,5 Most of MEN1-related gastrinomas are in the duodenum, often being small and multiple.6

Although indications for surgery are quite well established for insulinomas and nonfunctioning PENs larger than 2 to 3 cm, there is considerable controversy about the management of smaller PENs and particularly of gastrinomas. In the past, surgery has rarely been curative and several authors conclude that the multicentricity of gastrinomas preclude surgical cure,7,8 and suggest pharmacologic treatments, such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and/or somatostatin analogs. Other authors recommend resection of tumors only when they are larger than 3 cm in diameter.9,10 However, tumors larger than 3 cm in diameter are often associated with increased metastatic risk and consequent reduced curability.10,11 Since the enucleation or limited resection of PENs in MEN1 rarely results in definitive cure, early surgical intervention has been recommended to avoid malignant progression of PENs.12–14 A small study was carried out with more aggressive surgery, such as pancreatoduodenectomy (PD).15 It is clear that controversy exists about the surgical procedure to be adopted in MEN1 gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) neoplasms.16

This report describes and discusses the results of pancreatic resections performed for gastrinomas and other PENs in 16 MEN1 patients over a decade.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Diagnostic Procedures

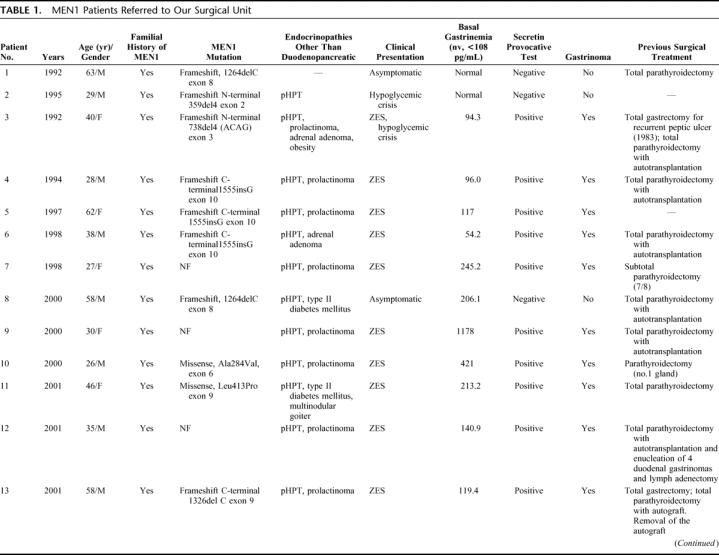

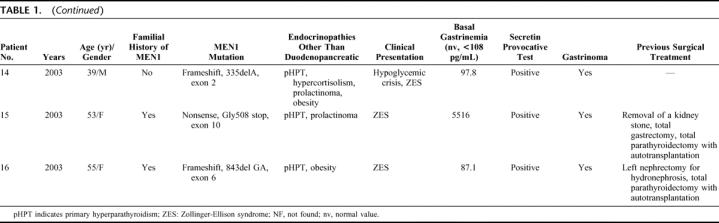

All the 16 patients were referred from the Regional Referral Center for Hereditary Endocrine Tumors at the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Careggi, Florence, to the Surgical Unit of the Department of Clinical Physiopathology of the University of Florence, between 1992 and 2003 with a clinical diagnosis of MEN1 (Table 1). The diagnosis was also genetically confirmed in 15 patients. A genetic test was performed on germline DNA obtained from peripheral blood leukocytes, as previously described.17 Written informed consent, in accordance with a protocol approved by the Local Institutional Review Board for human studies, was obtained from all the enrolled patients.

TABLE 1. MEN1 Patients Referred to Our Surgical Unit

TABLE 1. (Continued)

The diagnosis of PENs was based on serum gastrin, chromogranin A (CgA), pancreatic polypeptide (PP), somatostatin (SS), glucagon, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) levels. A preoperative secretin provocative test was performed in all patients. When hypoglycemia was suspected, a 48-hour fasting test was performed. Age, sex, family history of MEN1, associated endocrinopathies, clinical presentation, and brief clinical history are shown in Table 1. All patients were affected by primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT) and the majority (13 patients) of them had undergone subtotal or total parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation. Only 1 patient showed recurrent hypergastrinemia after previous enucleation of 4 duodenal gastrinomas with regional lymph adenectomy and 3 patients underwent total gastrectomy for peptic ulcer disease and enucleation of 1 PEN in 1 case, without any surgical treatment of the gastrinomas (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasonography (US), abdominal computed tomography (CT), somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SSRS-Octreoscan), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), or selective pancreatic angiography with hepatic venous sampling after selective arterial secretin injection (SASI) test were done in the majority of these patients to assess indications for surgery. The SASI test was performed following the procedure previously described by Imamura et al.18,19

The indications for surgery were established by the presence of hypergastrinemia, insulinoma, or pancreatic nodule(s) larger than 1 cm in diameter. Surgical intervention included: 1) complete duodenopancreatic mobilization, and colo-epiploic division; 2) inspection and palpation of the pancreas, duodenum, and first jejunal loops; 3) duodenopancreatic intraoperative US (IOUS); 4) transillumination of the duodenum; and 5) intraoperative serum gastrin measurement (IGM) by rapid immunoradiometric assay. For intraoperative gastrin assessment blood samples were drawn from a peripheral vein, collected in tubes and maintained at 4°C, at the induction of anesthesia (basal value), 15, 30 and 45 minutes after PD. Further samples were obtained postoperatively at 3, 4, and 24 hours. Gastrin values were measured with the rapid radioimmunoassay for serum gastrin using specific antibodies (100% cross-reactivity) for little gastrin (G-17) (Clinical Assays Gammadab Gastrin 125I RIA kits, Sorin Biomedica, Italy) after 10-minute incubation of the samples at 37°C in a shaker at 350 rpm. In patient number 16, gastrin assessment was made after secretin injection at the end of PD. The same samples were then controlled using the standard (60 minutes incubation at room temperature) method.

Surgical Treatment

Nonfunctioning PENs larger than 1 cm in size or insulinomas in the pancreatic body and tail were enucleated if possible; otherwise, they were resected. Distal pancreatectomy was performed only if multiple pancreatic body and/or tail nodules were present that could not be enucleated. Regional lymph adenectomy was always performed. In cases of hypergastrinemia with evidence of duodenal localization of gastrinomas, a PD was preferred. Pylorus-preserving Whipple's PD (PPWPD), according to Traverso-Longmire, was the procedure of choice until 1995; afterward, the standard Whipple's PD (WPD) became the PD routinely performed in our Center. Lymph adenectomy of the peripancreatic region, of the hepatoduodenal ligament, and of the hepatic and celiac arteries was performed in all treated patients.

Follow-up

Fasting serum gastrin, other entero-hormone levels, and a secretin provocative test were performed at 3 and 6 months postoperatively and yearly thereafter. Cure of hypergastrinism was defined as a normal serum gastrin concentration and a negative secretin test. An abdominal US and/or a CT scan were performed once every 2 years or, if required, at the time of high hormonal levels.

RESULTS

Preoperative Diagnosis

Thirteen of 16 (81%) patients were affected by Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES), 1 by hyperinsulinism and 2 by both the conditions. Two patients were asymptomatic (Table 1). The levels of basal serum gastrin were increased (117 to 5516 pg/mL; mean ± SD, 906.3 ± 1761; median, 213 pg/mL) when compared with normal values (<108 pg/mL) in 9 patients. Patient number 8, who was hypergastrinemic (206 pg/mL) but with a negative secretin provocative test, was later diagnosed as having chronic atrophic gastritis according to gastric biopsies after gastroscopy and was found to be gastrinoma-free at the histopathologic findings. The preoperative secretin provocative test was positive for hypergastrinemia in the 13 patients affected by gastrinoma.

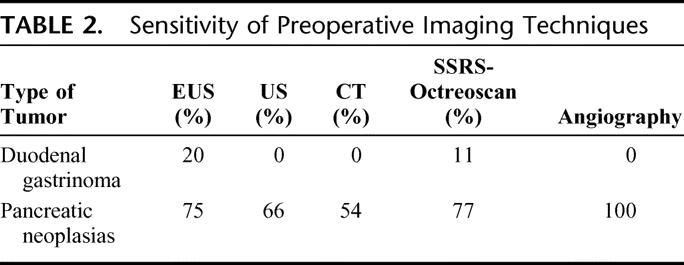

CT scan was able to detect the largest number of nonfunctioning PENs and/or in insulinomas, although other methods, such as US and EUS, also gave satisfactory results. However, EUS was found to be the most sensitive preoperative imaging technique for duodenal gastrinomas (Table 2). The diagnostic procedures used for localization of the duodenal gastrinomas in our patients indicated that: 1) none of the duodenal tumors was evidenced by US or CT; 2) EUS visualized a duodenal nodule in 1 of 6 studied patients; and 3) SSRS-Octreoscan detected a duodenal tumor in this latter patient, but it did not show duodenal gastrinomas in 10 other investigated patients.

TABLE 2. Sensitivity of Preoperative Imaging Techniques

The SASI test, performed in 11 patients, was negative in 7 of them, with no significant increase of gastrin after selective stimulation. The test showed significant increase of gastrin at multiple sites in 4 patients, after stimulation in the gastroduodenal artery (in 3 cases), in the superior mesenteric artery (in 3 cases), in dorsal pancreatic artery (in 1 case), and in the splenic artery (in 2 cases).

Intraoperative Diagnostic Tests

Inspection, palpation, and IOUS were used in all patients to localize both pancreatic and duodenal nodules. At least one pancreatic lesion could be found by these means in all operated patients, while a duodenal gastrinoma was diagnosed this way in only 3 of 12 patients with a duodenal localization: using duodenal transillumination in 2 cases and IOUS in the remaining one.

Surgical Procedures

Ten WPD and 3 PPWPDs were performed, 3 other patients received a distal pancreatectomy; patients number 5 and 8 who underwent a WPD also received a limited tail resection to remove small nodules that could not be safely enucleated. In these 2 cases, the whole pancreatic body and some of the tail were left in situ. Further associated procedures are listed in Table 3. The pancreatic resection was usually performed along the axis of the mesenteric vein. The PD was extended to the pancreatic body in 2 patients whereas further macroscopic nodules were found. The enucleation of 2 pancreatic lesions located in the left pancreas was performed in 2 other patients. Two associated pancreatic tail resections were necessarily due to the presence of large nodules. A pancreato-jejunal anastomosis was carried out in 10 cases, while in the remaining 3, this reconstruction was avoided, abandoning the pancreatic stump after ligature of the Wirsung's duct. Cholecystectomy was always carried out along with the PD and biliary-jejunal anastomosis was performed by means of an absorbable running suture at the level of the common hepatic duct. In 1 case, a total pancreatectomy (TP) was the surgical choice, due to the presence of large cystic tumors involving all the pancreatic tissue. In patient number 2, affected by nonfunctioning PENs and insulinoma and in patient number 14, affected by nonfunctioning PENs, hypercortisolism, insulinoma, and one duodenal gastrinoma, a distal pancreatectomy was performed. In both cases, one further nodule was enucleated near the cephalic region of the pancreas. In patient number 14, a local excision of the duodenal gastrinoma and a right adrenalectomy were also carried out. We also report (in patient number 11) the excision of an ectopic primary gastrinoma of the extrahepatic biliary confluence. This particularly rare localization has, to our knowledge, never been described in MEN1-related gastrinomas. Liver metastases were found in 2 patients (12%) who all underwent synchronous wedge or segmental hepatic resections.

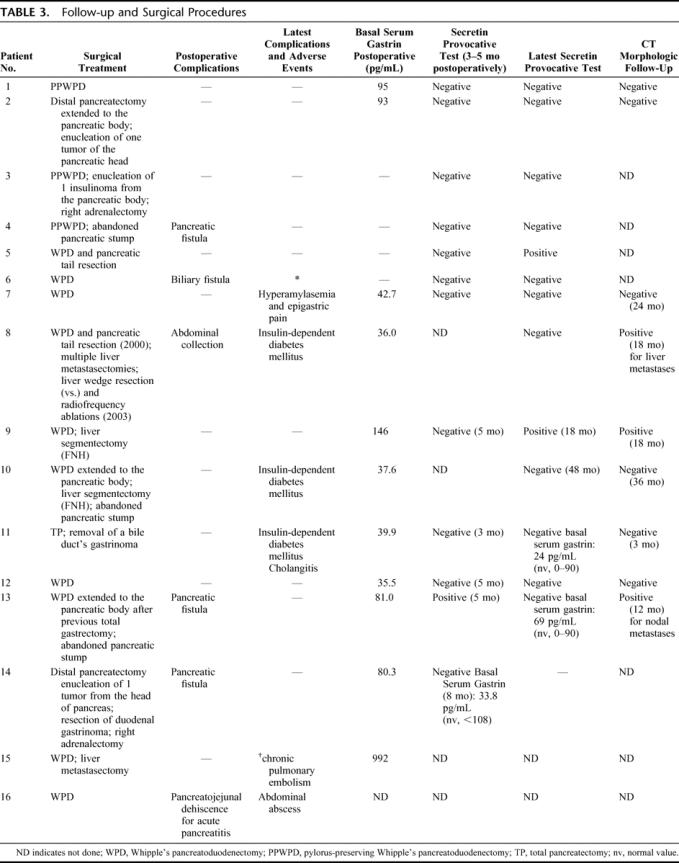

TABLE 3. Follow-up and Surgical Procedures

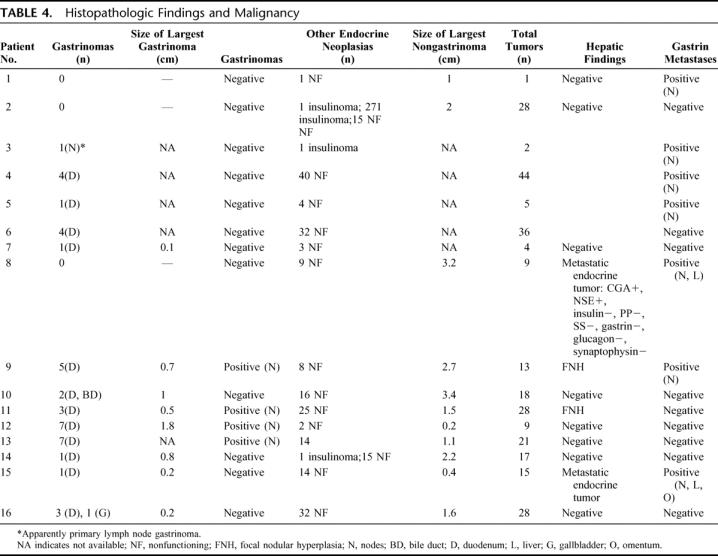

Histopathologic Findings

PENs were found in all 16 patients operated on and a total of 318 neuroendocrine tumors were excised (range, 2–44 tumors/patient). Forty one (13%) of the excised tumors were positive for gastrin at immunohistochemical evaluation (Table 4). Only 3 patients (19%) were gastrinoma-free; 93% (38 of 41) of the gastrinomas were identified by the pathologist in the II or the III portion of the duodenum. No pancreatic gastrinomas could be found in our series. One apparent primary gastrinoma in a peripancreatic lymph node was found in patient number 3, and it was confirmed by his disease-free status postresection. Two further ectopic gastrinomas were found in 2 patients with duodenal gastrinomas, respectively, in the gallbladder and in the extrahepatic biliary confluence.

TABLE 4. Histopathologic Findings and Malignancy

Overall malignancy was established in 10 patients (62%) by the finding of peripancreatic or periduodenal lymph nodes, liver, and omental metastasis in 1 case. Table 4 differentiates the metastases from gastrinoma in those cases where the pathologist could clearly state immunohistochemically the gastrin positivity. Two patients (12%) were found with gastrin negative hepatic metastases from endocrine tumor. Two cases thought to be liver metastases intraoperatively were then diagnosed as focal nodular hyperplasia by the pathologist.

Complications and Follow-up

No in-hospital deaths were observed. Overall postoperative complications occurred in 6 patients (37%). The complication rate specific for pancreatic fistulas and pancreato-jejunal anastomotic leak was 27%, as 4 of 15 resected patients experienced various degrees of anastomotic failure: 3 pancreatic fistulas, defined as more than 10 mL/day of amylase rich fluid (>1000 U/mL) from the drains at day 7, 1 biliary fistula, 1 abdominal abscess, and 1 dehiscence of the pancreato-jejunal anastomosis, radiologically (CT) demonstrated, secondary to acute pancreatitis. This latter complication required reoperation with TP. The other complications were treated conservatively or by percutaneous drainage, with total remission in all cases (Table 3). All patients previously treated with gastric antisecretory drugs did not need this therapy after surgery.

Five patients (31%) developed later complications, such as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and cholangitis (3 patients) and recurrent episodes of epigastric pain and hyperamylasemia (1 patient). Malabsorption could be found after suppression of enzymatic substitutive therapy (2 patients).

Ten patients (77%) of the 13 with positive gastrin provocative test and histologically proved gastrinoma showed both basal and stimulated normal gastrin levels 3 to 5 months after PD, while 2 patients (15%) showed high stimulated gastrin values, respectively, 5 and 18 months after surgery. Basal gastrin was shown to be increased only in 2 (15%) patients at the first postoperative test. CT scan evidenced regional nodal recurrence 18 months after surgery in 2 patients. The 3 patients affected by insulinoma are still asymptomatic.

Three patients died of causes unrelated to the initial disease (1 in a car accident and 2 because of heart failure) at various times during the follow-up, while being normogastrinemic and apparently disease-free. Patient number 15 died 13 months after surgery with chronic pulmonary embolism while eugastrinemic; the postmortem investigation showed no recurrence of gastrinoma, while a well-differentiated endocrine tumor (NSE+, CGA+, synaptophisin+, glucagon+, insulin−, somatostatin−, and gastrin−) could be found in the residual pancreas.

At present, there are no radiologic images of PENs in any of the cured patients, but 1 patient has nodal recurrence in the absence of hormonal increase 18 months after surgery. All 13 alive patients are enjoying a good social and work life.

Prognostic Value of Intraoperative Gastrin Measurement

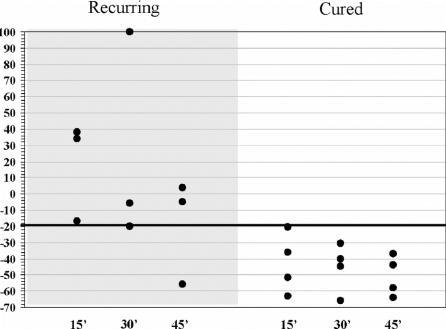

Rapid intraoperative gastrin measurement was carried out in 8 patients (Fig. 1). Basal values were normal in 1 patient, slightly elevated in 6 patients (mean value, 144.6 pg/mL; range, 118–209 pg/mL) and markedly increased (1339 pg/mL) in 1 patient. All of them showed normal gastrin levels after 24 hours.

FIGURE 1. Intraoperative gastrin decay according to recurring (gray column) or cured (white column) gastrinomas. x-axis reports times from surgical removal of tumor, and y-axis indicates basal gastrin fall (as described in the text) as percentage. Gastrin's fall more than 30% from baseline was considered curative for our series.

Normal gastrin values were obtained 15 minutes after PD in 3 patients and a progressive decrease in hormonal levels was observed during the following 24 hours. None of these patients showed any recurrence at the present follow-up. Three of the other 5 patients who did not show prompt normalization of gastrin values or a significant decrease (>20% after 30 minutes. postresection), were found hypergastrinemic at follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of MEN1-related PENs is still controversial.16,20 Medical therapy plays a primary role in the control of symptoms in ZES, with achievement of relief from gastric hypersecretion by PPIs and inhibition of hormone secretion in VIPomas, glucagonomas, GRFomas, SSomas, or carcinoids by somatostatin analogs.21 No controversy exists about the role of surgery for the insulinomas, as it is demonstrated to be curative in this case.

In MEN1 patients affected by PENs, hypoglycemia has a 20% prevalence, with one or more macroscopic (>0.5 cm) localizations.22 However, also in MEN1 insulinoma(s), other pancreatic tumors are often present, making surgical planning difficult. A suggested surgical approach is represented by the removal of all pancreatic nodules found intraoperatively using palpation or IOUS. The presence of multiple, large and deep pancreatic nodules may make pancreatic resection necessary, even though insulinomas are benign tumors.23 Our experience suggests that surgery is curative when resection of the affected pancreatic tissue and enucleation of macroscopic nodules in the residual pancreas are performed as indicated by other studies, where permanent cure is achieved with this aggressive surgical approach.23,24

At present, no medical therapy is available to delay the tumoral growth of either symptomatic or asymptomatic PENs in MEN1 and the role of surgery as a definitive cure or prevention of metastatic disease is still debated. Malignant disease is evident in about one half of middle-aged patients, and it can be expected to occur from 1 to 3 decades after diagnosis when affected kindreds are accurately screened in a multimodal fashion.2 It seems to be clear that affected patients may belong to 2 different groups: one with aggressive behavior and the other one with indolent course even in the presence of metastases.11 Factors predictive of these differences are not available.25 These 2 populations could not be segregated genetically.26,27 This can lead to different behaviors, ranging from an early surgical approach, with inconsistent treatment of similar patients among different Surgical Centers, to simple surveillance and surgical abstention.

The lack of imaging techniques (US, CT, magnetic resonance, and SSRS-Octreoscan) sensitive enough to ensure final tumor detection and its follow-up, makes serologic PEN biomarkers helpful tools for the surgeon's decision making.2,12,15 This is especially true for gastrinomas whose surgical timing should be determined by hypergastrinemia alone, even in the absence of visible lesions.15 Prospective studies showed that, among the possible imaging techniques, only the EUS is sensitive enough to localize gastrinomas with 40% to 50% sensitivity.28,29 Other approaches such as the SASI test may be used preoperatively to detect the region responsible for pathologic gastrin secretion.19 In selective venous sampling by portal venous cannulation for gastrin measurement, the blood samplings are obtained from several different veins draining the pancreas. The test's sensitivity ranges between 60% and 90% and requires considerable expertise with a significant complications rate.30 The SASI test is based on the principle that secretin injection induces a prompt release of gastrin from gastrinoma cells. In a report by Imamura et al, 7 patients affected by sporadic ZES underwent successfully curative resection of gastrinomas less than 1 cm in diameter.18 One limitation of this technique is that it cannot accurately distinguish duodenal gastrinomas from those arising in the head or in the uncinate process of the pancreas because the arteries feeding these areas are the same. Furthermore, the anastomoses between the feeding pancreatic arteries can determine false-positive localization (ie, the secretin injection in the splenic artery can stimulate gastrin secretion by a gastrinoma in the duodenum or in the head of pancreas). Our experience confirms that both conventional imaging techniques and SASI test are largely inadequate for localization of the primary tumors.

Apart from the timing of surgery, another controversial issue is the extent of surgery in MEN1 PENs.31 There is a general agreement that TP should be avoided, except in the case of multiple and diffuse macroscopic nodules. If the mass is deeply localized and/or involves contiguous tissues, the treatment of choice is a pancreatic resection; when smaller lesions are identified, enucleation is performed for tumors sited in the head of pancreas, while distal pancreatectomy is suggested for left-sited PENs even if they could be simply enucleated. Generally, a regional lymph adenectomy is carried out in both procedures.31,32

This conservative approach is due to the early and delayed postoperative complications that PD is thought to cause. PD is certainly an aggressive procedure because of the operative risks and long-term metabolic complications. However, in the hands of experienced surgeons, postoperative mortality and morbidity (risk of diabetes mainly) due to PD have been progressively reduced and are becoming quite acceptable. Oncologically PD is a more radical operation, as the duodenum is almost always the site where multiple gastrinomas develop in MEN1 patients.

The treatment of gastrinomas in MEN1 is controversial. According to several surgeons, gastrinomas should be enucleated or resected with surrounding tissues.31–33 This is particularly true when located in the duodenum. Duodenal gastrinomas can be approached by a wide longitudinal duodenotomy and if the tumor is less than 5 mm, it can be enucleated from the submucosa by means of an elliptical mucosal incision. Gastrinomas larger than 5 mm should be ablated with an adequate margin through a full-thickness excision of the duodenal wall. The nodes around the pancreatic head, common duct, portal vein, and hepatic artery must be excised to assure a curative resection. As a consequence of this conservative surgery, the majority of patients are not definitively cured and recurrence of hypergastrinemia, as well as metastatic disease, is possible.15 In the experience of Thompson et al, only one third of patients submitted to this procedure had a negative secretin stimulation test, even if most of them (68%) remained eugastrinemic and some asymptomatic without the need for any medical therapy for a long postoperative period.34 For all these reasons, an aggressive surgical approach involving PD has been claimed to allow a more radical resection and a better curability.15,19,35,36

From the very beginning, we chose the strategy of the ablation of all the macroscopic pancreatic tumors found at surgery, of the nodal and hepatic metastases, if present, and of the gastrinomas. Therefore, for multiple reasons, PD became our elective surgical approach to these pathologic patterns. First, gastrinomas are more frequently found in the duodenum in MEN1 patients; therefore, development of new tumors can be prevented by this procedure. Second, PD makes radical treatment of the peripancreatic nodal lesions and of those that are possibly found in the head of pancreas possible. Third, cephalic macroscopic PENs can be treated by PD as well, and tumors on the left side of the mesenteric vessels can be removed by extending the PD to include part of the pancreatic body. Fourth, a simple enucleation can be added to PD if PENs are found more distally in the left pancreas. This strategy allowed us to preserve pancreatic tissue not involved by macroscopic tumor and to reduce the risk of pancreatitis, the damage of the Wirsung's duct, and the development of recurrences and/or malignant tumors and of recurrences. Only in 1 case did we have to perform a TP because of the diffuse presence of macroscopic tumors within the pancreas, while in another case a TP was necessary as a rescue because of the postoperative occurrence of acute pancreatitis of the pancreatic stump with disruption of the pancreato-jejunal anastomosis.

A literature review evidenced that in a few cases of MEN1-associated gastrinomas, treatment with PD was accompanied by a high rate of curability.15,36 Our observations in 16 MEN1 patients affected by PENs showed an overall curability of 75%, since 12 of 16 of our patients are, at the present follow-up (6–108 months from surgery) or were, at the moment of their death for other causes unrelated to tumor recurrence or progression, eugastrinemic, and free from radiologic signs of local and metastatic tumor relapse. Patient number 8, who was found gastrinoma-free, with nonfunctioning PENs and with nodal and liver metastases, was then radiologically (abdominal CT) diagnosed with recurrent disease in the liver 18 months after surgery.

We are reporting a 77% of curability for MEN1-related gastrinoma since 10 of 13 patients affected by ZES were disease-free at follow-up. These results can justify an aggressive surgical procedure like PD since the mortality due to surgery in this series is 0%, and the overall complications rate we report (37%) is quite similar to those generally observed by others.37,38

Pancreatic fistulas and pancreato-enteric leaks should be discussed apart; indeed, in MEN1 patients, PD could be a riskier procedure because pancreatic and biliary anastomoses are surgically challenging, both because of the soft pancreatic texture and small size (<3 mm) of the common duct. Under these circumstances, complications involving the pancreato-jejunal anastomosis, such as fistulas and dehiscences, are reported to increase from 25%37,39 to 38%.38 In the present series the reported 27% rate of pancreatic fistulas/dehiscence should not be a contraindication to PD, especially in consideration of the fact that all our patients had a soft pancreas with small ducts and that the definition of pancreatic fistula we adopted is quite liberal and included also those “biochemical” leaks, which are usually prone to spontaneous remission. To limit these complications, in some patients with a particularly soft pancreas, we chose to avoid the anastomosis and to simply suture the pancreatic stump. This procedure can expose the patient to the risk of a collection of pancreatic juice or of a pancreatic fistula, but these complications are usually solved in a few weeks by supportive therapy.

WDP is a very radical operation; pyloric and perigastric nodes and the gastric antrum with part of the fundus40 can be removed with real benefit in MEN1-ZES patients showing gastric carcinoids. Indeed, these lesions may arise either in the antral or fundic mucosa and possibly with an aggressive course.41,42 The limits of a WDP are represented by dumping syndrome, maldigestion, and malabsorption.

On the other hand, although PPWPD is a less radical operation, it may prevent long-term nutritional complications permitting a normal gastric emptying and small bowel absorption with complete restoration of preoperative body weight.43 Gastroenteric hormonal release also appears well preserved with this technique. In consideration of the risk of persistence or recurrence of gastrinomas in the residual duodenal mucosa, we performed a PPWPD in only 2 patients, preserving about 1 to 1.5 cm of duodenal mucosa. Furthermore, PPWPD could bear the risk of postoperative delayed gastric emptying and of marginal ulceration at the duodenojejunostomy.43 Severe malabsorption is an uncommon complication of PD, and an excellent quality of life is also reported after WPD.44 Thus, the possible benefits of PPWPD should be carefully balanced versus the risk of performing a less radical operation.

Intraoperative rapid gastrin measurement is used to assess the thoroughness of surgery. In patient number 11, the test effectively changed the operative strategy, leading to the excision of an extrahepatic biliary duct nodule after a TP was concluded without a decrease in serum gastrin levels. After the nodule was excised, serum gastrin levels dropped within the normal range and the pathologist's report confirmed the lesion to be a gastrinoma. Results from our limited experience cannot really state whether such a technique could be used to direct the care of patients postoperatively. The 3 patients who showed a recurrence belong to the group of 5 patients whose gastrin levels did not drop below the above-mentioned cutoff. There are few data published in the literature,45 and this test will need confirmation in a larger number of patients. Several technical issues need to be solved, such as the exact assessment of the hormone half-life and the methodologic bias linked to the possible detection of circulating inactive fragments of the gastrin molecule. Serum gastrin levels measured by the rapid assay are higher than those measured by the standard assay. Hopefully, the intraoperative secretin provocative test could overcome these limitations as the data from Kato et al demonstrated that a negative test is indicative of a radical resection.46 However, this method also needs further data to become a standard evaluation in these disorders.

CONCLUSION

MEN1-associated PENs should be considered a surgically curable disease. Pancreatic resection seems to be the correct approach to this disease, providing a high rate of curability and acceptable morbidity. Future studies should attempt to create multicenter networks where similar diagnostic and surgical procedures are carried out in larger cohorts of patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Mary Forrest, Managing Editor, Journal of Chemotherapy, for her skilled assistance in revising the English.

Footnotes

Supported by Cofin M.I.U.R. 2003 (to F.T.), by A.I.R.C. 2000 (to M.L.B.), and by the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (to M.L.B.).

Reprints: Francesco Tonelli, MD, Department of Clinical Physiopathology, Unit of Surgery, University of Florence, Medical School, V.le G.B. Morgagni 85, 50134 Florence, Italy. E-mail: f.tonelli@dfc.unifi.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vasen HF, Lamers CB, Lips CJ. Screening for the multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type I: a study of 11 kindreds in The Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:2717–2722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skogseid B, Eriksson B, Lundqvist G, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: a 10 years prospective screening study in four kindreds. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx SJ. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS., et al. eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease, 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lairmore TC, Chen VY, De Benedetti MK, et al. Duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg. 2000;231:909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen RT. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: recent advances. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(suppl 4):170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pipeleers-Marichal M, Somers G, Willems G, et al. Gastrinomas in the duodenum of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:723–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mignon M, Ruszniewski P, Podevin P, et al. Current approach to the management of gastrinoma and insulinoma in adults with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. World J Surg. 1993;17:489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lips CJ. Clinical management of the multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes: results of a computerized opinion poll at the Sixth International Workshop on Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia and von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Intern Med. 1998;243:589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norton JA, Jensen RT. Unresolved surgical issues in the management of patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg. 1991;15:151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacFarlane MP, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Prospective study of surgical resection of duodenal and pancreatic gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surgery. 1995;118:973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibril F, Venzon DJ, Ojeaburu JV, et al. Prospective study of the natural history of gastrinoma in patients with MEN1: definition of an aggressive and a nonaggressive form. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:582–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skogseid B, Oberg K, Eriksson B, et al. Surgery for asymptomatic pancreatic lesion in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. World J Surg. 1996;20:872–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson NW, Bondeson AG, Bondeson L, et al. The surgical treatment of gastrinoma in MEN I syndrome patients. Surgery. 1989;106:1081–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norton JA, Douglas LF, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery to cure the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartsch DK, Langer P, Wild A, et al. Pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: surgery or surveillance? Surgery. 2000;128:958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandi ML, Gagel RF, Angeli A, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of MEN type 1 and type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5658–5671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morelli A, Falchetti A, Martineti V, et al. MEN1 gene mutation analysis in Italian patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imamura M, Takahashi K, Isobe Y, et al. Curative resection of multiple gastrinomas aided by selective arterial secretin injection test and intraoperative secretin test. Ann Surg. 1989;210:710–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imamura M, Takahashi K. Use of selective arterial secretin injection test to guide surgery in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg. 1993;17:433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veldhuis JD, Norton JA, Wells SA Jr, et al. Surgical versus medical management of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mozell E, Woltering EA, O'Dorisio TM, et al. Effect of somatostatin analog on peptide release and tumor growth in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:476–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kloppel G, Willemer S, Stamm B, et al. Pancreatic lesions and hormonal profile of pancreatic tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type I: an immunocytochemical study of nine patients. Cancer. 1986;57:1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demeure MJ, Klonoff DC, Karam JH, et al. Insulinomas associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I: the need for a different surgical approach. Surgery. 1991;110:998–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Riordain DS, O'Brien T, van Heerden JA, et al. Surgical management of insulinoma associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I. World J Surg. 1994;18:488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton JA, Alexander HR, Fraker DL, et al. Comparison of surgical results in patients with advanced and limited disease with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 2001;234:495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kouvaraki MA, Lee JE, Shapiro SE, et al. Genotype-phenotype analysis in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Surg. 2002;137:641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dotzenrath C, Goretzki PE, Cupisti K, et al. Malignant endocrine tumors in patients with MEN1 disease. Surgery. 2001;129:91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruszniewski P, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, et al. Localization of gastrinomas by endoscopic ultrasonography in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surgery. 1995;117:629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proye C, Malvaux P, Pattou F, et al. Noninvasive imaging of insulinomas and gastrinomas with endoscopic ultrasonography and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy. Surgery. 1998;124:1134–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burcharth F, Stage JG, Stadil F, et al. Localization of gastrinomas by transhepatic portal catheterization and gastrin assay. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:444–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Åkerström G, Hessman O, Skogseid B. Timing and extent of surgery in symptomatic and asymptomatic neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas in MEN1. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;386:558–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson NW. Surgical treatment of the endocrine pancreas and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in the MEN1 syndrome. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1992;40:195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton JA, Alexander HR, Fraker DL, et al. Comparison of surgical results in patients with advanced and limited disease with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 2001;234:495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson NW. Current concepts in the surgical management of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 pancreatic-duodenal disease: results in the treatment of 40 patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, hypoglycaemia or both. J Intern Med. 1998;243:495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delcore R, Friesen SR. Role of pancreatoduodenectomy in the management of primary duodenal wall gastrinomas in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surgery. 1992;112:1016–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stadil F. Treatment of gastrinomas with pancreatoduodenectomy. In: Mignon M, Jensen RT, eds. Endocrine Tumors of the Pancreas: Recent Advances in Research and Management, vol. 23. Frontiers of Gastrointestinal Research. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1995:333–341. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, et al. Selection of pancreaticojejunostomy techniques according to pancreatic texture and duct size. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1044–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang YM, Tian XD, Zhuang Y, et al. Risk factors of pancreatic leakage after pancreatoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2456–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe K, et al. Does prophylactic octreotide decrease the rates of pancreatic fistula and other complications after pancreatoduodenectomy? Ann Surg. 2000;232:419–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLeod RS, Taylor BR, O'Connor BI, et al. Quality of life, nutritional status and gastrointestinal hormone profile following the Whipple procedure. Am J Surg. 1995;169:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rindi G, Bordi C, Rappel S, et al. Gastric carcinoids and neuroendocrine carcinomas: pathogenesis, pathology and behavior. World J Surg. 1996;20:168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bordi C, Corleto VD, Azzoni C, et al. The antral mucosa as a new site for endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndromes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2236–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin PW, Lin YJ. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muller MW, Friess H, Berger HG, et al. Gastric emptying following pylorus-preserving Whipple and duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Proye C, Pattou F, Carnaille B, et al. Intraoperative gastrin measurement during surgical management of patients with gastrinomas: experience with 20 cases. World J Surg. 1998;22:643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kato M, Imamura M, Hosotani R, et al. Curative resection of microgastrinomas based on the intraoperative secretin test. World J Surg. 2000;24:1425–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]