Abstract

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) comprises a heterogeneous group of disorders. The most frequent subtype is caused by increased PMP22 gene dosage or missense point mutations affecting the PMP22 gene (CMT type 1A; CMT1A). Animal models in rat and mouse with the corresponding PMP22 alterations are available and mimic many aspects of the human diseases. Detailed examinations of the animal mutants, together with complementary data from patients, point towards altered Schwann cell–neurone interactions as a major underlying mechanism of CMT1A and related hereditary neuropathies. This is evident from the finding that mutated proteins affecting either Schwann cells or neurones have a profound influence on their partner cells. Recently, a number of novel genes causing various forms of CMT have been identified which are expressed either mainly by Schwann cells and/or by the accompanying neurones. These genes can be viewed, in analogy to classic experiments routinely performed in lower vertebrates, as the result of a ‘functional screen’ revealing crucial players in the interactions between Schwann cells and neurones. Studying how Schwann cell and axon-encoded proteins are functionally interconnected will be an exciting task for the future. It will not only yield insights into the molecular and cellular basis of neuropathies but also provide crucial information about the interplay between Schwann cells and neurones in general.

Keywords: Charcot—Marie—Tooth disease, Schwann cells

Introduction

Charcot—Marie—Tooth disease (CMT), also termed ‘hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies’ (HMSN), includes a clinically and genetically diverse group of disorders affecting the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The different classes of CMT have been divided by clinical and electrophysiological means into demyelinating forms (CMT1, CMT3 and CMT4) and axonal forms (CMT2). This distinction has proved to be very valuable for diagnostic purposes. As a consequence, myelinopathies (characterized by decreased nerve conduction velocity, NCV) and axonopathies (slightly reduced to normal NCV but reduced compound muscle action potential, CMAP) have been traditionally viewed as quite different diseases affecting either the Schwann cells or the neurones and their extensions (Dyck et al. 1993). Recent data from careful genotype/phenotype correlation studies, combined with approaches aimed at the elucidation of molecular and cellular disease mechanisms, have somewhat revised this picture. Pathological signs of myelinopathies and axonopathies often appear mixed and interconnected. In particular, specific mutations in the protein zero gene (MPZ/P0) or the connexin32 gene (GJB1/Cx32) lead to CMT2 although the vast majority of mutants in these genes are classified as CMT1 (reviewed by Chapon et al. 1999; De Jonghe et al. 1999; Mostacciuolo et al. 1999; Vance, 1999; Misu et al. 2000; Young & Suter, 2001). The molecular basis for these observations remains obscure but the fact remains that P0 expression has not been found in motor and sensory neurones (reviewed by Hagedorn et al. 1999; Sommer & Suter, 1998; Lee et al. 2001). Thus it appears very likely that the observed CMT2 phenotype is due to mutation-dependent disease mechanisms that profoundly alter Schwann cell—neurone interactions.

It has long been appreciated that the development of myelinated axons requires some of the most complex interactions among different cell types in the nervous system. In this review, we focus on how these interactions in the PNS might be perturbed in various neuropathies, with an emphasis on CMT. A unifying theory will be developed that these disorders should be viewed in the context of the complex cellular organization of the entire peripheral nerve and the communication between Schwann cells, neurones, fibroblasts, resident macrophages, invading cells of the immune system, and components of the extracellular matrix.

The influence of myelinating Schwann cells on neurones

Myelinating Schwann cells have a profound effect on determining axonal properties (reviewed by Martini, 2001). Especially during myelination, Schwann cells mediate the clustering and spacing of sodium channels in the axonal membrane providing the basis for efficient saltatory impulse propagation. Schwann cells also arrange the spatial separation of sodium channels from voltage-dependent potassium channels and are intimately involved in the structural and functional organization of the node of Ranvier and adjacent structures (reviewed by Arroyo & Scherer, 2000; Peles & Salzer, 2000).

At the node of Ranvier, another interesting phenomenon is observed with regard to the size of the axon. The axonal calibre is reduced, neurofilament phosphorylation is diminished, and probably as a consequence, neurofilament density is increased, presumably due to the reduced repellent negative charges on the neurofilament side arms (de Waegh et al. 1992; Mata et al. 1992).

The influence of axons on Schwann cells

Schwann cells are critically dependent on their neuronal counterparts for survival and proper differentiation in early development (reviewed by Jessen & Mirsky, 1998; Lobsiger et al. 2002). Later in development, the interplay between axon and Schwann cell determines that large-calibre axons (diameter larger than 1μm) will be myelinated while small-calibre axons remain engulfed by non-myelinating Schwann cells but no myelin is formed. Furthermore, a tight correlation between axonal diameter and myelin thickness has been noted in many species (see References in Elder et al. 2001). The precise building of such a defined structure is also likely to be dependent on tight Schwann cell—axon communication. However, the interpretation that myelin thickness in the PNS is mainly dependent on axonal diameter has recently been questioned (Elder et al. 2001). This study showed that a genetically induced reduction in axonal calibre does not cause a reduction in the extent of myelination and indicates that Schwann cells read some intrinsic signal on axons that can be uncoupled from axonal diameter. Since the evidence was based on the analysis of neurofilament-deficient mice, some caution may be warranted, as the axonal properties were significantly altered in these animals. Other morphological observations that hint at regulation by Schwann cell—neurone interactions include the correlation between the internodal length of the myelin sheath and axon calibre, and the finding that Schwann cells (in contrast to their central nervous system counterpart, the oligodendrocyte) myelinate large-calibre axons always in a 1:1 relationship under normal physiological conditions.

The reader may have realized (and be complaining by now) that, in the last two paragraphs, the authors have tried to separate the influences of axons and Schwann cells onto each other, mainly for didactic reasons. Indeed, some evidence exists that in some of the processes mentioned above, the Schwann cell or the neurone provide the crucial first piece of information (for review, see Martini, 2001). However, it appears likely that these are only ‘initial triggers’ that are immediately followed by signal transduction events mediating reciprocal interactions between the cell types involved.

Impaired Schwann cell—neurone interactions in CMT1A and corresponding animal models

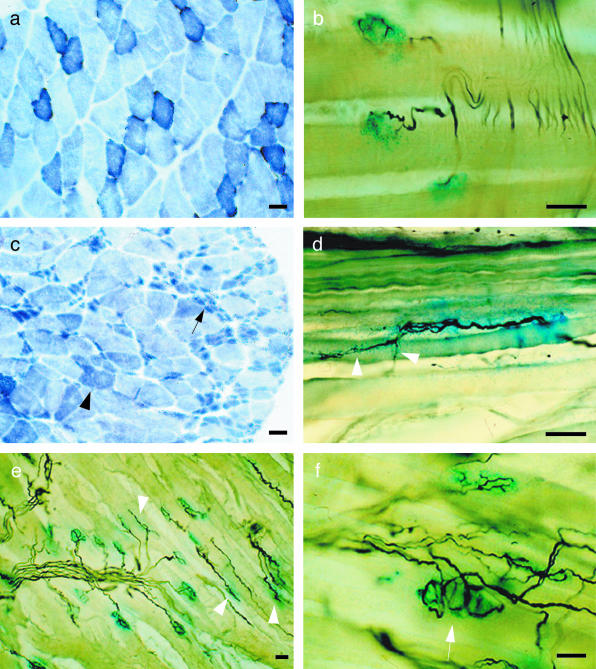

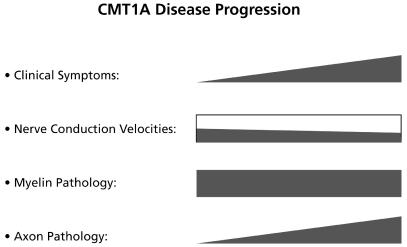

Mutations and altered gene dosage of the PMP22 gene are responsible for the majority of CMT (subtype CMT1A; reviewed by Suter & Snipes, 1995; Young & Suter, 2001). PMP22 is an integral membrane protein (Taylor et al. 2000b; reviewed by Naef & Suter, 1998) that is a significant component of compact PNS myelin (Spreyer et al. 1991; Welcher et al. 1991; Snipes et al. 1992; Haney et al. 1996; reviewed by Jetten & Suter, 2000; Berger et al. 2002). Transgenic mice (Huxley et al. 1996; Magyar et al. 1996; Huxley, 1998; Sancho et al. 1999, 2001; Norreel et al. 2001) and rats (Sereda et al. 1996; Niemann et al. 2000) have been generated that carry additional copies of the PMP22 gene. These animals mimic many pathological hallmarks of the human disease and show classical segmental demyelination. Supernumerary Schwann cells forming ‘onion bulb’ structures have also been observed (Sereda et al. 1996). Mice with altered copy numbers of the PMP22 gene develop a pronounced distal axonopathy that correlates with the clinical progression of the disease (Sancho et al. 1999). Furthermore, affected muscles were atrophied with pathological hallmarks of denervation and nerve sprouting (Fig. 1). The neuromuscular junctions appeared disorganized and showed polyinervation and ultraterminal sprouting of nerve endings, similar to the findings in Trembler (Tr) mice (Gale et al. 1982) that carry a missense point mutation in the Pmp22 gene (Suter et al. 1992b). Thus these animal models are affected by pronounced axonal damage, most likely secondary to the alterations affecting myelinating Schwann cells (although some minor expression of PMP22 in motor and sensory neurones should be noted (Parmantier et al. 1995, 1997) (Fig. 2). Additional support for axonal alterations has been provided by elegant studies using the Tr mouse (Suter et al. 1992b). In these animals, peripheral nerve demyelination is associated with neurofilament hypophosphorylation and increased neurofilament density (similar to the previously described situation at the nodes of Ranvier in normal nerves; de Waegh et al. 1992). These data are consistent with findings on nerve biopsies of CMT1 patients that included marked hypophosphorylation of neurofilaments and an increased relative abundance of beta tubulin isotypes 2 and 3 (Watson et al. 1994). The authors note that ‘the axonal cytoskeleton in CMT1 resembles that of immature nerve fibres. A failure of normal Schwann cell–axon interaction in CMT1 may prevent full differentiation of the axonal cytoskeleton of myelinated nerve fibers’. In another study, severe impairments of the axonal cytoskeleton were also observed in CMT1A xenografts (Sahenk et al. 1999). The potential importance of the axonal component in CMT1 had already been recognized long before (Virchow, 1855) and has been reiterated later in the light of available genetic data (Thomas et al. 1997). Recently, another evaluation of a cohort of CMT1A patients carrying the PMP22-containing chromosomal duplication revealed that reduced compound motor and sensory nerve action potentials correlate with clinical disability, while motor NCV does not (Krajewski et al. 2000) (Fig. 3). Further correlative longitudinal studies of muscular atrophy and disease progression have not yet been performed but are warranted. Furthermore, a detailed analysis of the effects of different CMT-causing mutations on the neuromuscular junction, at least in animal models, would be justified (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Histochemical analysis of hindlimb muscles in 6-month-old wildtype (a,b) and PMP22 overexpressing animals (c–f; Magyar et al. 1996). (a,c) On cross-sections of gastrocnemius muscle a standard histochemical staining for succinate-dehydrogenase (complex II of the respiratory chain; Nachlas et al. 1957) was performed and showed single atrophied, triangle-shaped muscle fibres (c, arrowhead) and massive loss of muscle fibres leading to fascicular muscle atrophy (c, arrow). (b,d,e,f) To visualize the neuromuscular junctions (NMJ) and intramuscular nerve branches, a histochemical staining for acetylcholinesterase activity (blue) and a silver-based nerve-staining (black) according to Pestronk & Drachman (1978) was performed on 50 μm longitudinal sections through the soleus (b,d) and gastrocnemius (e,f) muscles. In atrophied muscles of the mutants ultraterminal sprouting (d, arrowheads) and elongated endplates with abnormal morphology (e, arrowheads) as well as polyinervation of NMJ (f, arrow) can be observed. Scale bars = 20 μm.

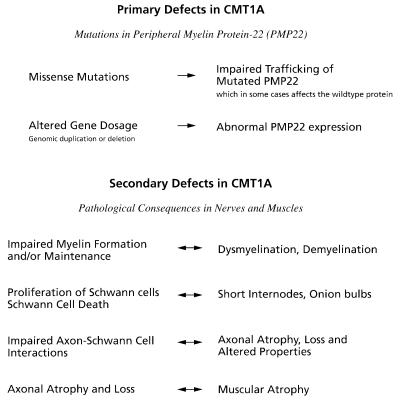

Fig. 2.

Primary and secondary defects in the pathomechanism of Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1A (CMT1A) peripheral neuropathy with their related pathological consequences in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Correlation of the progression of different clinical hallmarks in CMT1A.

It can be concluded that neurological dysfunction and clinical disability in CMT1 are caused by a loss or damage to large-calibre motor and sensory axons opening new avenues for potential treatment strategies aimed at neuronal maintenance (reviewed by Kamholz et al. 2000; Young & Suter, 2001). Other approaches may include correction of the particular mutations directly. In CMT1A due to PMP22 duplication, this might be achieved by normalizing PMP22 expression (Hai et al. 2001). However, the success of such strategies is dependent on whether PMP22 overexpression causes reversible or irreversible damage to the mutant Schwann cell, the associated axons and atrophied muscles. (Perea et al. 2001) have partially answered this question by analysing a conditional CMT1A mouse model in which PMP22 overexpression could be induced or repressed by tetracycline (for technical review, see Mansuy & Suter, 2000). Rapid remyelination of the demyelinated nerves was observed when PMP22 expression was normalized in adult animals. Whether significant axonopathy and muscular atrophy also developed and were reversible could not be resolved due to the limited cellular efficiency of the system.

Several other studies support a critical role of Schwann cell–neurone interactions in PNS dysmyelination caused by PMP22 alterations. This includes heterozygous PMP22 knock-out mice (animal models for hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies, HNNP; Adlkofer et al. 1997; reviewed by Berger et al. 2002), mice lacking PMP22 (homozygous PMP22 knock-out animals; Adlkofer et al. 1995; Sancho et al. 1999, 2001) and mice carrying PMP22 missense mutations (models for rare and usually severe forms of CMT1A; Suter et al. 1992a, 1992b; Valentijn et al. 1992; Ionasescu et al. 1997; Isaacs et al. 2000). Mice lacking PMP22 completely showed delayed myelination suggesting some function of PMP22 in the initial phases of Schwann cell differentiation to a myelinating phenotype (Adlkofer et al. 1995). If PMP22 gene dosage is highly increased in transgenic mice or rats, nearly complete amyelination is observed (Magyar et al. 1996; Sereda et al. 1996), and abnormalities in the initiation of myelination, the ensheathment of the axon by the Schwann cell, and the extension of this cell along the axon have been observed in Trembler-J and moderately PMP22-overexpressing mice (Robertson et al. 1999).

Axons are involved in the regulation of Schwann cell proliferation through development and in regeneration (reviewed by Jessen & Mirsky, 1998). Axonal signals are also most probably responsible for the generation of supernumerary Schwann cells forming ‘onion bulb’ structures in CMT1A and other demyelinating neuropathies. Detailed analysis of Schwann cell proliferation has been carried out in PMP22-mutant mice (Sancho et al. 2001). Indeed, Schwann cell proliferation was increased in these mouse strains later in development, most likely as the result of exposure to axon-associated mitogen. Consistent with the observed axonal alterations in CMT1A animals, molecular analysis of the regulatory cell cycle component cyclin D1 revealed that this special type of Schwann cell proliferation is related to injury-induced proliferation rather than Schwann cell proliferation in early development (Atanasoski et al. 2001, Atanasoski et al. 2002).

At the cellular level, peripheral nerves of PMP22 knock-out mice which develop focal hypermyelination, followed by myelin degeneration and axonal atrophy have been examined for the distribution of other components of the myelin sheath including myelin basic protein (MBP), E-cadherin, and myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), and the delayed rectifying potassium channel Kv1.1 as a membrane protein of axons (Neuberg et al. 1999). Hypomyelinated fibres lost the focally restricted E-cadherin and Kv1.1 expression suggesting that demyelination has a strong effect on myelin as well as axonal protein expression and localization.

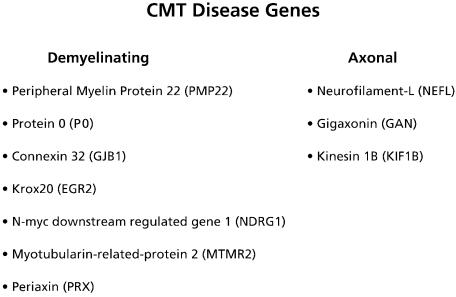

Altered proteins in other forms of CMT

Recent progress in genetics has identified a number of additional genes that are mutated in different forms of CMT (for an updated summary, see http://molgen-www.uia.ac.be/CMTMutations). Broadly speaking, the proteins involved can be classified as mainly expressed by Schwann cells and/or neurones (Fig. 4). P0 (mutated in CMT1B) is an adhesion protein in compact myelin and Cx32 (CMT1X) is found in an uncompacted region of the myelin sheath where it may mediate a shortcut connecting the abaxonal and adaxonal cytoplasm of the myelinating Schwann cell (reviewed by Snipes & Suter, 1995). Periaxin (PRX; CMT4F) occurs in two isoforms due to alternative splicing (Dytrych et al. 1998). S-periaxin is restricted to the cytoplasm (Dytrych et al. 1998) and L-periaxin is found in the plasma membrane of myelinating Schwann cells (Sherman & Brophy, 2000). In the abaxonal Schwann cell membrane, L-periaxin forms a complex with dystrophin-related-protein-2 (DRP2) and dystroglycan linking the cytoskeleton of the Schwann cell with the extracellular matrix (Sherman et al. 2001). EGR2/Krox-20 is a zinc finger transcription factor that plays a major role in PNS development (reviewed by Mirsky & Jessen, 1999) and regulates the expression of myelin proteins including PMP22, P0, Cx32 and periaxin (Nagarajan et al. 2001). Since mutations affecting all of those proteins lead to demyelinating neuropathies, these findings provide a compelling rational why EGR2 mutation cause a similar form of demyelinating CMT.

Fig. 4.

Different subtypes of Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease are linked to several mutations. According to electrophysiology (NCV) and pathology these genes can roughly be grouped into demyelinating and axonal types of CMT.

Animal models for null mutations of P0, Cx32, Prx and EGR2/Krox-20 are available (reviewed by Berger et al. 2002). Of particular interest with regards to Schwann cell–neurone interactions are Mpz knock-out mice. Although P0 is expressed by Schwann cells and not by either motorneurones or sensory neurones, these mice show not only severe dysmyelination but also a pronounced axonal pathology (Frei et al. 1999). Furthermore, heterozygous Mpz-deficient mice, an animal model for CMT1B due to null mutations, revealed a pronounced influence of invading cells of the immune system on the observed pathology (Schmid et al. 2000; Carenini et al. 2001).

A mutation in the N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 (NDRG1) is the origin of the hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy-LOM (HMSNL). HMSNL is a severe autosomal recessive neuropathy initially identified in the gypsy community of the Bulgarian town of Lom (Kalaydjieva et al. 2000). NDRG1 is expressed by Schwann cells and may play some role in the control of cell proliferation and differentiation. Mutations in the myotubularin-related-protein-2 (MTMR2; CMT4B) gene are responsible for a rare form of recessively inherited severe CMT which is characterized by focally folded myelin sheaths (Gambardella et al. 1998; Bolino et al. 2000, Bolino et al. 2001). MTMR2 is a member of the myotubularin gene family that may act as dual specificity phosphatases (Laporte et al. 1998). However, their main substrates are probably phosphorylated phosphoinositides (Blondeau et al. 2000; Taylor et al. 2000a). For both of these autosomal recessive forms of demyelinating CMT, no animal models are available.

Primary axonal forms of dominant CMT (CMT2) are associated with mutations in the gene encoding the neurofilament light chain (NEFL; CMT2E; Mersiyanova et al. 2000; De Jonghe et al. 2001), or the microtubule motor kinesin KIF1B (CMT2A; Zhao et al. 2001). Nefl knock-out mice develop normally and do not exhibit an overt phenotype indicating that CMT2E is likely caused by a gain-of-function or dominant-negative mechanism (Zhu et al. 1997). Heterozygous Kif1B knock-out mice have a defect in transporting synaptic vesicle precursors and suffer from progressive muscle weakness similar to human neuropathies. Thus these mice may be a suitable animal model for the disease (Zhao et al. 2001).

Mutations in the gigaxonin (GAN) gene lead to the severe, autosomal recessive giant axonal neuropathy affecting the peripheral and central nervous system (Bomont et al. 2000). The GAN protein has characteristics of proteins involved in the organization of the actin network. Consistent with this notion, giant axonal neuropathy includes neurofilament accumulation, leading to segmental distension of axons, and a generalized disorganization of the intermediate filaments in endothelial cells, Schwann cells and keratinocytes. This causes the hallmarks of the disease including severe neuropathy, ataxia and curled, kinky hair (reviewed by Ouvrier, 1989).

Altered neurone–Schwann cell interactions as the common theme in motor and sensory neuropathies

If we summarize the current knowledge about the molecular and cellular basis of CMT, it becomes apparent that the cell types building the peripheral nerves are in constant and crucially important communication with each other and the extracellular matrix. When axons are associated with mutant Schwann cells, their calibre is reduced and their cytoskeleton is severely altered. Studies in animal models have established that, most probably as a consequence of the axonal atrophy and cytoskeletal rearrangements, axonal transport is reduced and this observation provides a good hypothesis as to why axons degenerate predominantly at the distal ends of long nerves (de Waegh et al. 1992). However, it is unlikely that the myelinated peripheral nerve is regulated in only ‘one-way streets’. It appears more plausible that initial damage to one cell type that is directly affected by the specific mutation starts a cascade of events that is reciprocally regulated between the interacting partners. Such an interpretation follows the established concept of the finely tuned interactions between neurones and Schwann cells in development (reviewed by Jessen & Mirsky, 1999; Lobsiger et al. 2002). Following this intellectual path, it is not surprising that besides mutations of myelin-associated proteins (PMP22, P0, Cx32) and their regulator (EGR2/Krox-20), mutations affecting proteins that connect the Schwann cell with the basal lamina (periaxin), components of the axonal cytoskeleton (gigaxonin, neurofilament light chain), and molecular motors (kinesin KIF1B) have been found as causes of CMT. Damage due to toxic insult or genetic aberrations to one of the cell types involved in CMT is likely to have a deleterious effect also on the partner. This may explain why the differences between demyelinating and axonal forms of CMT are often blurry when carefully examined. Understanding the interplay between Schwann cells, their associated neurones, endoneurial fibroblasts, macrophages, and the protecting perineurial sheath may hold the key to the understanding of disease mechanisms in CMT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants of the Swiss National Science Foundation, the NCCR ‘Neural Plasticity and Repair’, the Swiss Muscle Disease Foundation, the Wolfermann-Nägeli Stiftung and the Swiss Bundesamt for Science related to the Commission of the European Communities, specific RTD programme ‘Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources’, QLK6-CT-2000-00179.

References

- Adlkofer K, Martini R, Aguzzi A, Zielasek J, Toyka KV, Suter U. Hypermyelination and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy in Pmp22-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:274–280. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlkofer K, Frei R, Neuberg DH, Zielasek J, Toyka KV, Suter U. Heterozygous peripheral myelin protein 22-deficient mice are affected by a progressive demyelinating tomaculous neuropathy. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:4662–4671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo EJ, Scherer SS. On the molecular architecture of myelinated fibers. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2000;113:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s004180050001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasoski S, Shumas S, Dickson C, Scherer SS, Suter U. Differential Cyclin D1 Requirements of proliferating Schwann cells during development and after injury. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:581–592. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasoski S, Scherer SS, Nave KA, Suter U. Proliferation of Schwann cells and regulation of cyclin D1 expression in an animal model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;67:443–449. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger P, Young P, Suter U. Molecular cell biology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neurogenetics. 2002 doi: 10.1007/s10048-002-0130-z. In press DOI 10.1007/s10048-002-0130-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau F, Laporte J, Bodin S, Superti-Furga G, Payrastre B, Mandel JL. Myotubularin, a phosphatase deficient in myotubular myopathy, acts on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2223–2229. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.hmg.a018913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolino A, Muglia M, Conforti FL, LeGuern E, Salih MA, Georgiou DM, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 4B is caused by mutations in the gene encoding myotubularin-related protein-2. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:17–19. doi: 10.1038/75542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolino A, Lonie LJ, Zimmer M, Boerkoel CF, Takashima H, Monaco AP, et al. Denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography of the myotubularin-related 2 gene (MTMR2) in unrelated patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease suggests a low frequency of mutation in inherited neuropathy. Neurogenetics. 2001;3:107–109. doi: 10.1007/s100480000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomont P, Cavalier L, Blondeau F, Ben Hamida C, Belal S, Tazir M, et al. The gene encoding gigaxonin, a new member of the cytoskeletal BTB/kelch repeat family, is mutated in giant axonal neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:370–374. doi: 10.1038/81701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carenini S, Maurer M, Werner A, Blazyca H, Toyka KV, Schmid CD, et al. The role of macrophages in demyelinating peripheral nervous system of mice heterozygously deficient in P0. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:301–308. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapon F, Latour P, Diraison P, Schaeffer S, Vandenberghe A. Axonal phenotype of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease associated with a mutation in the myelin protein zero gene. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1999;66:779–782. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.6.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe P, Timmerman V, Ceuterick C, Nelis E, De Vriendt E, Lofgren A, et al. The Thr124Met mutation in the peripheral myelin protein zero (MPZ) gene is associated with a clinically distinct Charcot-Marie-Tooth phenotype. Brain. 1999;122:281–290. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe P, Mersivanova I, Nelis E, Del Favero J, Martin JJ, Van Broeckhoven C, et al. Further evidence that neurofilament light chain gene mutations can cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2E. Ann. Neurol. 2001;49:245–249. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(20010201)49:2<245::aid-ana45>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck PJ, Chance P, Lebo R, Carney JA. Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Grffin JW, Low PA, Poduslo JF, editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993. pp. 1094–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Dytrych L, Sherman DL, Gillespie CS, Brophy PJ. Two PDZ domain proteins encoded by the murine periaxin gene are the result of alternative intron retention and are differentially targeted in Schwann cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5794–5800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GA, Friedrich VL, Jr, Lazzarini RA. Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes read distinct signals in establishing myelin sheath thickness. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001;65:493–499. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei R, Motzing S, Kinkelin I, Schachner M, Koltzenburg M, Martini R. Loss of distal axons and sensory Merkel cells and features indicative of muscle denervation in hindlimbs of P0-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:6058–6067. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06058.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale AN, Gomez S, Duchen LW. Changes produced by a hypomyelinating neuropathy in muscle and its innervation. Morphological and physiological studies in the Trembler mouse. Brain. 1982;105:373–393. doi: 10.1093/brain/105.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambardella A, Bolino A, Muglia M, Valentino P, Bono F, Oliveri RL, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in autosomal recessive hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy with focally folded myelin sheaths (CMT4B) Neurology. 1998;50:799–801. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn L, Suter U, Sommer L. P0 and PMP22 mark a multipotent neural crest-derived cell type that displays community effects in response to TGF-beta family factors. Development. 1999;126:3781–3794. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai M, Bidichandani SI, Hogan ME, Patel PI. Competitive binding of triplex-forming oligonucleotides in the two alternate promoters of the PMP22 gene. Antisense Nucl. Acid Drug Dev. 2001;11:233–246. doi: 10.1089/108729001317022232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney C, Snipes GJ, Shooter EM, Suter U, Garcia C, Griffin JW, et al. Ultrastructural distribution of PMP22 in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1996;55:290–299. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley C, Passage E, Manson A, Putzu G, Figarella-Branger D, Pellissier JF, et al. Construction of a mouse model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A by pronuclear injection of human YAC DNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:563–569. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley C. Myelin disorders. Neuropathol. Appl. Neuro. biol. 1998;24:87–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1998.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionasescu VV, Searby CC, Ionasescu R, Chatkupt S, Patel N, Koenigsberger R. Dejerine-Sottas neuropathy in mother and son with same point mutation of PMP22 gene. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:97–99. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199701)20:1<97::aid-mus13>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs AM, Davies KE, Hunter AJ, Nolan PM, Vizor L, Peters J, et al. Identification of two new Pmp22 mouse mutants using large-scale mutagenesis and a novel rapid mapping strategy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1865–1871. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.12.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Origin and early development of Schwann cells. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1998;41:393–402. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19980601)41:5<393::AID-JEMT6>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Schwann cells and their precursors emerge as major regulators of nerve development. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:402–410. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten AM, Suter U. The peripheral myelin protein 22 and epithelial membrane protein family. Prog. Nucl. Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2000;64:97–129. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)64003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaydjieva L, Gresham D, Gooding R, Heather L, Baas F, de Jonge R, et al. N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 is mutated in hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy-Lom. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:47–58. doi: 10.1086/302978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamholz J, Menichella D, Jani A, Garbern J, Lewis RA, Krajewski KM, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1: molecular pathogenesis to gene therapy. Brain. 2000;123:222–233. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski KM, Lewis RA, Fuerst DR, Turansky C, Hinderer SR, Garbern J, et al. Neurological dysfunction and axonal degeneration in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Brain. 2000;123:1516–1527. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J, Blondeau F, Buj-Bello A, Tentler D, Kretz C, Dahl N, Mandel JL. Characterization of the myotubularin dual specificity phosphatase gene family from yeast to human. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:1703–1712. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.11.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Calle E, Brennan A, Ahmed S, Sviderskaya E, Jessen KR, Mirsky R. In early development of the rat mRNA for the major myelin protein P (0) is expressed in nonsensory areas of the embryonic inner ear, notochord, enteric nervous system, and olfactory ensheathing cells. Dev. Dyn. 2001;222:40–51. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobsiger CS, Taylor V, Suter U. The early life of a Schwann cell. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:245–253. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magyar JP, Martini R, Ruelicke T, Aguzzi A, Adlkofer K, Dembic Z, et al. Impaired differentiation of Schwann cells in transgenic mice with increased PMP22 gene dosage. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5351–5360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05351.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansuy IM, Suter U. Mouse genetics in cell biology. Exp. Physiol. 2000;85:661–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini R. The effect of myelinating Schwann cells on axons. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:456–466. doi: 10.1002/mus.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata M, Kupina N, Fink DJ. Phosphorylation-dependent neurofilament epitopes are reduced at the node of Ranvier. J. Neurocytol. 1992;21:199–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01194978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersiyanova IV, Perepelov AV, Polyakov AV, Sitnikov VF, Dadali EL, Oparin RB, Petrin AN, Evgrafov OV. A new variant of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 is probably the result of a mutation in the neurofilament-light gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:37–46. doi: 10.1086/302962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky R, Jessen KR. The neurobiology of Schwann cells. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:293–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misu K, Yoshihara T, Shikama Y, Awaki E, Yamamoto M, Hattori N, et al. An axonal form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease showing distinctive features in association with mutations in the peripheral myelin protein zero gene (Thr124Met or Asp75Val) J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2000;69:806–811. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.6.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostacciuolo ML, Fabrizi GM, Bosello V, Cavallaro T, Schiavon F, Pinaroli C, et al. Description of mutations in Cx32 in Italian families with diagnosis of CMT1 and CMT2. J. Peripheral Nervous System. 1999;4:296–297. [Google Scholar]

- Nachlas MM, Tsou K-C, de Souza E. Cytochemical demonstration of succinic dehydrogenase by the use of a new p-nitrophenyl substituted ditetrazole. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1957;5:420–436. doi: 10.1177/5.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naef R, Suter U. Many facets of the peripheral myelin protein PMP22 in myelination and disease. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1998;41:359–371. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19980601)41:5<359::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan R, Svaren J, Le N, Araki T, Watson M, Milbrandt J. EGR2 mutations in inherited neuropathies dominant-negatively inhibit myelin gene expression. Neuron. 2001;30:355–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberg DH, Sancho S, Suter U. Altered molecular architecture of peripheral nerves in mice lacking the peripheral myelin protein 22 or connexin32. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;58:612–623. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19991201)58:5<612::aid-jnr2>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann S, Sereda MW, Suter U, Griffiths IR, Nave KA. Uncoupling of myelin assembly and schwann cell differentiation by transgenic overexpression of peripheral myelin protein 22. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4120–4128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04120.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norreel JC, Jamon M, Riviere G, Passage E, Fontes M, Clarac F. Behavioural profiling of a murine Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A model. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:1625–1634. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouvrier RA. Giant axonal neuropathy. A review. Brain Dev. 1989;11:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(89)80038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmantier E, Braun C, Thomas JL, Peyron F, Martinez S, Zalc B. PMP-22 expression in the central nervous system of the embryonic mouse defines potential transverse segments and longitudinal columns. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;378:159–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmantier E, Cabon F, Braun C, D'Urso D, Muller HW, Zalc B. Peripheral myelin protein-22 is expressed in rat and mouse brain and spinal cord motoneurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995;7:1080–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peles E, Salzer JL. Molecular domains of myelinated axons. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2000;10:558–565. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea J, Robertson A, Tolmachova T, Muddle J, King RH, Ponsford S, et al. Induced myelination and demyelination in a conditional mouse model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1007–1018. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestronk A, Drachman DB. A new stain for quantitative measurement of sprouting at neuromuscular junctions. Muscle Nerve. 1978;1:70–74. doi: 10.1002/mus.880010110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AM, Huxley C, King RH, Thomas PK. Development of early postnatal peripheral nerve abnormalities in Trembler-J and PMP22 transgenic mice. J. Anat. 1999;195:331–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.19530331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahenk Z, Chen L, Mendell JR. Effects of PMP22 duplication and deletions on the axonal cytoskeleton. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:16–24. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<16::aid-art5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho S, Magyar JP, Aguzzi A, Suter U. Distal axonopathy in peripheral nerves of PMP22-mutant mice. Brain. 1999;122:1563–1577. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.8.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho S, Young P, Suter U. Regulation of Schwann cell proliferation and apoptosis in PMP22-deficient mice and mouse models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Brain. 2001;124:2177–2187. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.11.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid CD, Stienekemeier M, Oehen S, Bootz F, Zielasek J, Gold R, et al. Immune deficiency in mouse models for inherited peripheral neuropathies leads to improved myelin maintenance. J. Neuro. sci. 2000;20:729–735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00729.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereda M, Griffiths I, Puhlhofer A, Stewart H, Rossner MJ, Zimmermann F, et al. A rat transgenic model for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuron. 1996;16:1049–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DL, Brophy PJ. A tripartite nuclear localization signal in the PDZ-domain protein L-periaxin. J. BiolChem. 2000;275:4537–4540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DL, Fabrizi C, Gillespie CS, Brophy PJ. Specific disruption of a Schwann cell dystrophin-related protein complex in a demyelinating neuropathy. Neuron. 2001;30:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snipes GJ, Suter U, Welcher AA, Shooter EM. Characterization of a novel peripheral nervous system myelin protein (PMP-22/SR13) J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:225–238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snipes GJ, Suter U. Molecular anatomy and genetics of myelin proteins in the peripheral nervous system. J. Anat. 1995;186:483–494. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer L, Suter U. The glycoprotein P0 in peripheral gliogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:11–16. doi: 10.1007/s004410051029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreyer P, Kuhn G, Hanemann CO, Gillen C, Schaal H, Kuhn R, et al. Axon-regulated expression of a Schwann cell transcript that is homologous to a ‘growth arrest-specific’ gene. EMBO J. 1991;10:3661–3668. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter U, Moskow JJ, Welcher AA, Snipes GJ, Kosaras B, Sidman RL, et al. A leucine-to-proline mutation in the putative first transmembrane domain of the 22-kDa peripheral myelin protein in the trembler-J mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992a;89:4382–4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter U, Welcher AA, Ozcelik T, Snipes GJ, Kosaras B, Francke U, et al. Trembler mouse carries a point mutation in a myelin gene. Nature. 1992b;356:241–244. doi: 10.1038/356241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter U, Snipes GJ. Biology and genetics of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1995;18:45–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GS, Maehama T, Dixon JE. Inaugural article: myotubularin, a protein tyrosine phosphatase mutated in myotubular myopathy, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000a;97:8910–8915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160255697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor V, Zgraggen C, Naef R, Suter U. Membrane topology of peripheral myelin protein 22. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000b;62:15–27. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001001)62:1<15::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PK, Marques W, Jr, Davis MB, Sweeney MG, King RH, Bradley JL, et al. The phenotypic manifestations of chromosome 17p11.2 duplication. Brain. 1997;120:465–478. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentijn LJ, Baas F, Wolterman RA, Hoogendijk JE, van den Bosch NH, Zorn I, et al. Identical point mutations of PMP-22 in Trembler-J mouse and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Nat. Genet. 1992;2:288–291. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance JM. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1999;883:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virchow R. Ein Fall von progressiver Muskelatrophie. Arch. Pathol. Anat. 1855;8:537. [Google Scholar]

- de Waegh SM, Lee VM, Brady ST. Local modulation of neurofilament phosphorylation, axonal caliber, and slow axonal transport by myelinating Schwann cells. Cell. 1992;68:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90183-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DF, Nachtman FN, Kuncl RW, Griffin JW. Altered neurofilament phosphorylation and beta tubulin isotypes in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1. Neurology. 1994;44:2383–2387. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welcher AA, Suter U, De Leon M, Snipes GJ, Shooter EM. A myelin protein is encoded by the homologue of a growth arrest-specific gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:7195–7199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P, Suter U. Disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic strategies in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Brain Res. Brain. Res. Rev. 2001;36:213–221. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Takita J, Tanaka Y, Setou M, Nakagawa T, Takeda S, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A caused by mutation in a microtubule motor KIF1Bbeta. Cell. 2001;105:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Couillard-Despres S, Julien JP. Delayed maturation of regenerating myelinated axons in mice lacking neurofilaments. Exp. Neurol. 1997;148:299–316. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]