Abstract

This study describes the distribution of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) antigen and its mRNA in seven species of cartilaginous fish from six elasmobranch families. Antigen was detected using antibodies to synthetic human PTHrP and the mRNA with a riboprobe to human PTHrP gene sequence. The distribution pattern of PTHrP in the cartilaginous fish studied, reflected that observed in mammals but PTHrP further occurs in some sites unique to cartilaginous fish. Of particular note was the demonstration of PTHrP in the shark skeleton, which although considered not to contain bone, may form by a process similar to that forming the early stages of mammalian endochondral bone. The distribution of PTHrP in the elasmobranch skeleton resembled the distribution of PTHrP in the developing mammalian skeleton. Differences in the staining pattern between antisera to N-terminal PTHrP and mid-molecule PTHrP in the brain and pituitary suggested that the PTHrP molecule might be post-translationally processed in these tissues. The successful use of antibodies and a probe to human PTHrP in tissues from the early vertebrates examined in this study suggests that the PTHrP molecule is conserved from elasmobranchs to humans.

Keywords: calcium-regulating hormone, cartilaginous, fish, immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization

Introduction

PTHrP is a mediator of humoral hypercalcaemia of malignancy (HHM), a condition in which restriction of calcium excretion by the kidney and release of calcium from bone results in high plasma calcium levels. Cloning (Suva et al. 1987) and sequencing (Moseley et al. 1987) revealed that PTHrP had N-terminal homology with parathyroid hormone (PTH), the main hypercalcaemic factor in higher vertebrates, which is produced by the parathyroid glands. Although little primary sequence homology exists between the two peptides beyond residues 1–13, conformational similarities over residues 1–34 allow PTH and PTHrP to activate a common PTH/PTHrP receptor in mammals (Jüppner et al. 1991). Aspects of the gene structure of PTH and PTHrP and their chromosomal localization suggest that these two proteins arose from an ancient gene duplication event (Ingleton & Danks, 1996). Subsequent studies showed that non-neoplastic tissues such as skin, kidney, muscle, bone, mammary tissue and neuroendocrine tissues in mammals also produce PTHrP (Philbrick et al. 1996). The widespread distribution of PTHrP in mammalian and avian (Schermer et al. 1991) tissues suggests multiple physiological roles. These appear to include the regulation of growth and differentiation of many cell types, relaxation of smooth muscle, skeletal development and the regulation of calcium transport across the placenta (Martin et al. 1997).

Fish lack encapsulated parathyroid glands, but PTH-like substances have been detected in fish plasma and brain (Harvey et al. 1987); Kaneko & Pang, 1987). However, fish PTH has not been isolated. More recently, immunohistochemical and radioimmunoassay data indicated that bony fish contain PTHrP (Danks et al. 1993). Little is known about the presence of PTH-like peptides in cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes), as bony fish have, until recently, been the main focus of research in the lower vertebrates. The cartilaginous fish are a phylogenetically ancient group that includes the sharks and rays. Two reports indicate that PTHrP peptides exist in Chondrichthyes. The dogfish, Scyliorhinus canicula, contains DNA that hybridizes with an oligonucleotide probe for chicken PTHrP (Chailleux et al. 1995 and an independent study demonstrated the presence of immunoreactive PTHrP in tissues from the same species (Ingleton et al. 1995).

The present study examined the distribution of immunoreactive PTHrP and PTHrP mRNA expression in tissues from seven species of Chondrichthyans from six different elasmobranch families. The aim of this study was to gain insight into PTHrP's tissue distribution in early vertebrates and determine whether that distribution was conserved from elasmobranchs to mammals. This information may be used to elucidate possible physiological roles in this group of vertebrates.

Methods

Tissue collection

All animals were obtained by researchers at the Marine and Freshwater Resources Institute (MAFRI) (Queenscliff, Victoria, Australia) from Port Phillip Bay (Victoria, Australia). The study was carried out within the guidelines of the St Vincent's Hospital Animal Ethics Committee. Animals were anaesthetized in a solution of 50 mg L−1 MS-222 (Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, MO, USA) then decapitated. Fresh samples of skin, kidney and liver were dissected from gummy sharks, Mustelus antarcticus (n = 10, one male, one female, remainder undetermined), school sharks, Galeorhinus galeus (n = 2, one male, one female), banjo sharks or Southern fiddler rays, Trygonorrhina fasciata (n = 5, three males, two females) and common spotted stingarees, Urolophus gigas (n = 2, unknown sex). An expanded range of tissues including gill, rectal gland, vertebrae, jaw, pancreas, spleen, heart and whole brain (in most cases including the pituitary) were collected from gummy sharks (n = 8, five males, three females), Australian angel sharks, Squatina australis (n = 6, two males, four females), southern eagle rays, Myliobatis australis (n = 4, two males, two females) and Port Jackson sharks, Heterodontus portusjacksoni (n = 3, two males, one female). Tissues were fixed in either 10% neutral buffered formalin (Orion Laboratories, Welshpool, Australia) for 12–24h, or Bouin Hollande Sublimate (BHS) (Kracier et al. 1967) for 48–72h. After dehydration and clearing, all tissues were embedded in paraffin.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Sections for immunohistochemistry were cut at 5μm and mounted on slides coated with 2% triethyoxypropyl silane (Sigma) in acetone. Rabbit antisera raised to synthetic human N-terminal PTHrP(1–14) and (1–16), and to the mid-molecule region of synthetic human PTHrP(67–84) were used. PTHrP IHC followed a standard immunoperoxidase technique (Sternberger et al. 1970; Danks et al. 1989). The antiserum to PTHrP(1–14) has previously been used on fish tissues (Danks et al. 1993; Ingleton et al. 1995). N-terminal antiserum used in the current study showed no cross-reactivity with human PTH either in Western blot or radioimmunoassay (Danks et al. 1989). All incubations were conducted at room temperature. Briefly, sections were dewaxed in two changes of xylene then washed in 100% ethanol. Immersion of sections in methanol with 1% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min blocked endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were washed in three changes of phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.6 (PBS), 60s each. Incubation in 10% normal swine serum (Institute of Medical and Veterinary Sciences, Adelaide, Australia), diluted in PBS/5% new born calf serum (NCS) (Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Melbourne, Australia), blocked non-specific binding sites. Excess swine serum was tipped off the slides after 30 min and the primary PTHrP antiserum applied at dilutions between 1:25 and 1:200 for 60 min. Human skin was used as a positive control in each assay and was stained at the same dilutions as the fish tissues. Unbound antiserum was washed off the slide in three changes of 5% NCS/PBS, 10 min each. The secondary antibody, swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), was diluted 1:40 in 5/% NCS/PBS and incubated with the sections for 30 min. After two 5-min washes in 5% NCS/PBS and one 5-min wash in PBS, the peroxidase antiperoxidase complex (Dako), diluted to 1:80 in PBS, was applied to the sections for 30 min. Sections were washed twice in PBS, 5 min each, then equilibrated in 0.05M Tris buffer (pH7.6). The slides were immersed in 200 mL 0.05m Tris buffer with 100mg 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) and 1mL hydrogen peroxide, for 7 min, to detect the antibody complex. After three washes in distilled water, each of 5 min, the sections were counterstained in Harris's haematoxylin, washed in distilled water and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Slides were cleared in xylene and mounted in DePeX®.

Tissues fixed in BHS were washed to remove mercuric chloride from the sections, and the above protocol was modified as follows. After dewaxing and washing in 100% ethanol, sections were immersed in 1% iodine, and then 5% sodium thiosulphate in distilled water, and finally washed in running tap water. The steps including and after the endogenous peroxidase block were not modified.

All tissues were assayed in duplicate and the controls included: (i) human skin as a positive tissue control in each experiment; (ii) non-immune rabbit serum substituted for the primary antibody served as the negative control in each experiment; (iii) the deletion of alternate layers of the antibody sandwich served as a method control; (iv) confirmation of the specificity of staining for the PTHrP antigen, by staining randomly selected sections with antiserum to human PTH(1–34) (BioGenex, San Raman, USA) or with an antiserum to chum salmon growth hormone as described by Danks et al. (1993).

In situ hybridization (ISH)

A 420-base-pair riboprobe to Exon VI of human PTHrP was labelled with digoxigenin (DIG) (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) to examine PTHrP mRNA expression. The probe spans a region that shows conservation among known PTHrP sequences and has been used to examine PTHrP mRNA expression in mammalian tissues (Kartsogiannis et al. 1997). The protocol employed an alkaline phosphatase detection system as described by Zhou et al. (1994) and Kartsogiannis et al. (1997). Steps before hybridization required sterile glassware and solutions diluted with water treated with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corporation, La Jolla, CA, USA) to remove RNase contamination. All steps were conducted at room temperature unless specified otherwise. Briefly, sections were dewaxed in three changes of xylene, hydrated through a graded ethanol series, and then washed in DEPC-water, 5 min at each step. Treating sections with 0.2M HCl for 20 min blocked endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity. Slides were washed in DEPC-water, two 15-min washes, and then equilibrated in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0/50 mM EDTA for 5 min. The crosslinks formed during fixation were digested by incubation with 2–4µg Proteinase K (Roche), diluted in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0/50 mM EDTA, for 30 min at 37°C. Washing the sections in 2 mg mL−1 glycine in DEPC-PBS for 5 min stopped the reaction. After washing in DEPC-PBS, two washes, each of 15 min, the sections were post-fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma)/PBS for 15 min. Sections were washed twice, 15 min each, in DEPC-PBS before prehybridization for 60 min at 42 °C in a buffer of 50% deionized formamide/5× SSC/2% blocking reagent (Roche)/0.02% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA)/0.1% N-laurosarcosine (Sigma). Prehybridization buffer was tipped off the slide and the hybridization buffer, containing the same constituents as the prehybridization buffer but with the addition of 4 ng mL−1 of labelled riboprobe, was added. Slides were hybridized overnight at 42 °C in a humid chamber.

Steps after hybridization did not require sterile glassware or Rnase-free solutions. Unbound probe was removed by a 15-min wash in 2× SSC at 37°C and by incubation with 25µg mL−1 RNase A (Roche)/2× SSC at 37°C for 30 min. Stringency washes, 15 min each, continued at 37°C in one wash of 2× SSC, two changes of 1× SSC and two changes of 0.1× SSC. Slides were equilibrated for 5 min in buffer 1 (0.1M maleic acid/0.15M NaCl) and non-specific binding sites blocked by a 30-min incubation in a blocking medium of PBS/30% non-immune rabbit serum/3% bovine serum albumin (Commonwealth Serum Laboratories)/0.1% Triton X-100. The primary antibody, sheep alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG immunoglobulins (Roche), was diluted 1:500 in blocking medium and applied for 60 min. Unbound antibody was removed with two 15-min washes in 0.3% Tween 20/buffer 1, and then a further 15-min wash in buffer 1 alone. Sections were equilibrated in buffer 3 (100mM Tris pH9.5/100 mM NaCl/50mM MgCl2) for 3 min. Slides were then placed in a chromogen with 45µL 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (Roche) and 35µL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-phosphate (Roche) as the substrate, diluted in 10mL buffer 3 that had been filtered through a 0.2-μm filter (Acrodisc, MI, USA). Slides were left overnight in the dark for colour to develop. They were then washed in distilled water and counterstained in Nuclear Fast Red (Sigma) or Fast Green (Sigma). Sections were mounted in Clearmount (Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA), then DePeX.

All tissues were assayed in duplicate and a panel of controls was included in each experiment: (i) human skin served as the positive control tissue in each experiment; (ii) sections treated with 150μg mL−1 RNase A (Roche)/2× SSC, 2h at 37°C prior to hybridization acted as a negative control; (iii) the specificity of the anti-DIG sheep polyclonal antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) was confirmed using no probe controls with antibody, and endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity was assessed using no probe slides with antibody omitted as a standard.

Von Kossa staining

Von Kossa staining (Bancroft & Stevens, 1990) of undecalcified sections identified areas of calcified cartilage in elasmobranch vertebrae. Safranin O (Sigma), 1%, was used as a counterstain.

Analysis of IHC and ISH results

Results from immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization were examined by light microscopy. Sections were considered to stain positive for the PTHrP antigen if brown staining was observed or, in the case of the PTHrP mRNA, if purple/blue hybridization signal was visible. Scores for the intensity of staining for the PTHrP antigen and hybridization for PTHrP mRNA were given. Scores were presented as: –, no staining (or hybridization) in the tissue;+, weak;++, moderate; and +++, strong. In tissues where different cell types showed different intensities of staining or hybridization, scores were given for each major cell type. The variation in staining or hybridization intensity between different experiments was accounted for by comparing the human skin positive controls included in every experiment for both the immunohistochemical and the hybridization studies.

Results

The distribution of immunoreactivity and hybridization signal was similar in all the elasmobranchs studied. Unless otherwise stated, PTHrP immunoreactivity and hybridization signal were confined to the cell cytoplasm and the patterns of staining between the N-terminal and mid-molecule antibodies were the same, except in the case of the brain and pituitary. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of PTHrP antigen and mRNA in elasmobranch tissues, and presents the scores given for the intensity of staining or hybridization in each tissue. No staining was observed when PTH antiserum or an unrelated rabbit antiserum was used.

Table 1.

Summary of PTHrP distribution in elasmobranch tissues by IHC and ISH

| Tissue | Cell/structure type | IHC | ISH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | epidermal cells | + | + |

| mature denticles | – | – | |

| developing denticles | ++ | +++ | |

| dermis | – | – | |

| Muscle | skeletal | ++ | ++ |

| cardiac | + | + | |

| Gill | lamellar epithelium | + | + |

| interlamellar epithelium | ++ | +++ | |

| Kidney | proximal and distal tubules | ++ | ++ |

| neck segments | – | + | |

| glomeruli | – | + | |

| Rectal gland | tubular epithelium | ++ | + |

| canal epithelium | + | ++ | |

| Liver | hepatocytes | – | – |

| vessel and duct epithelium | + | + | |

| Pancreas | acinar cells | – | – |

| vessel and duct epithelium | + | + | |

| Spleen | erythrocyte-rich area | + | + |

| lymphocyte-rich area | – | – | |

| Notochord | inner sheath cells | – | – |

| outer sheath cells | + | + | |

| epithelial cells | + | ++ | |

| vacuolated notochordal cells | ++ | ++ | |

| Vertebrae | cartilage matrix | – | – |

| perichondrium | + | + | |

| uncalcified chondrocytes | ++ | ++ | |

| calcified chondrocytes | – | – | |

| Jaw and teeth | epithelium | ++ | not done |

| odontoblasts | ++ | not done | |

| chondrocytes | – | not done | |

| Brain | neurones in tectum | + | + |

| choroid epithelium | + | + | |

| saccus vasculosus epithelium | + | + | |

| Purkinje cells | + | + | |

| preoptic neurones* | ++ | – | |

| Spinal cord | grey matter | + | ++ |

| white matter | – | – | |

| canal epithelium | + | + | |

| Pituitary | neurointermediate lobe* | + | + |

| pars distalis | + | + |

Scores: −, no staining (or hybridization) in the tissue; +, weak; ++, moderate; and +++, strong. *Staining pattern varied between Nterminal and mid-molecule antisera.

Skin

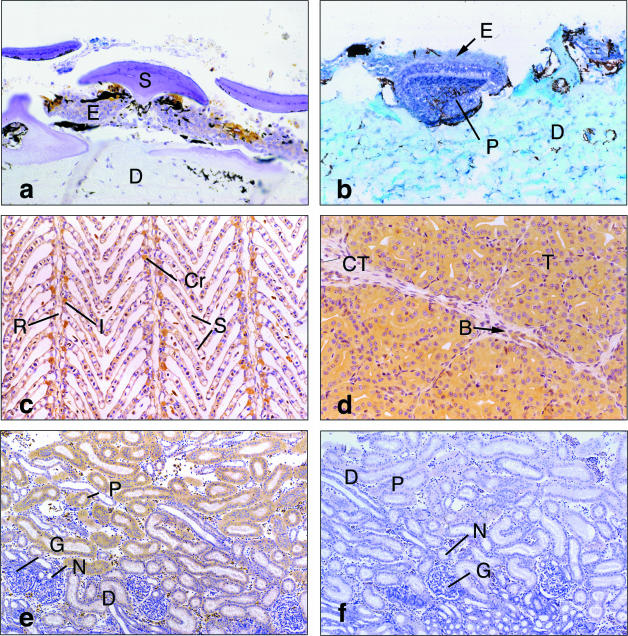

Moderate PTHrP immunoreactivity was observed in the epidermal cells immediately next to the dermal denticles in elasmobranch skin but was weak throughout the remainder of the epidermis (Fig.1a). In animals where prominent dermal denticles were absent, such as the spotted stingaree, PTHrP antigen was observed in cells in the basal layers of the epidermis (not shown). Hybridization signal for PTHrP mRNA was evenly distributed throughout the epidermal cells in sharks and rays (Table 1). There was no immunoreactivity or hybridization signal in mature dermal denticles and the dermis (Fig. 1a,b and Table 1). The epithelial cells and dermal cells (odontoblasts) of developing denticles contained PTHrP immunoreactivity (Table 1) and mRNA (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

(a) Gummy shark skin immunostained with PTHrP(1–14) antiserum. PTHrP antigen is seen in the epidermis (E), immediately adjacent to the spine (S) of the mature dermal denticle, with weaker staining throughout the remainder of the epidermis, but not in the dermis (D). Pigment (black) is visible. (×110). (b) In situ hybridization of gummy shark skin showing PTHrP mRNA in the epithelium (E) and pulp cavity (P) of developing denticles. Weak signal for the PTHrP mRNA occurs throughout the remainder of the epidermis but not in the dermis (D) (×110). (c) Section of shark gill immunostained with N-terminal PTHrP antiserum showing PTHrP antigen in the crypt or ‘chloride’ cells (Cr), epithelium of the interlamellar (I) and secondary lamellar (S) epithelium. The PTHrP antigen is not seen in the gill ray (R). (×110). (d) Tubules (T) in angel shark rectal gland are tightly packed and interspersed with connective tissue (CT). PTHrP immunoreactivity is seen in tubular epithelial cells and in scattered blood cells (B) but not in the connective tissue. (×110). (e) PTHrP immunohistochemistry showing PTHrP antigen in proximal (P) and distal (D) tubules of the kidney. Antigen is absent from the neck segments (N) and glomeruli (G). (×55). (f) Non-immune control of 1e, showing absence of PTHrP staining (lettering as in 1e, ×55).

Muscle

PTHrP antigen and mRNA were seen in skeletal and cardiac muscle but not within connective tissue dispersed within the muscle (Table 1).

Gill

PTHrP immunoreactivity (Fig. 1c) and hybridization signal (Table 1) occurred in the interlamellar epithelium, and the crypt or ‘chloride’ cells of the gill. Weaker staining was seen in the epithelial cells of the secondary lamellae (lamellar epithelium). The gill rays and cartilage in the gill bar showed little or no PTHrP immunoreactivity, and did not hybridize the PTHrP riboprobe.

Rectal gland and kidney

Epithelial cells of the secretory tubules and the central canal of the rectal gland reacted with PTHrP antisera (Fig. 1d) and the PTHrP riboprobe (Table 1). Staining and hybridization were not seen in the connective tissue between tubules and the mucous cells in the central canal epithelium. The proximal and distal tubules in the kidney displayed PTHrP immunoreactivity while the glomeruli, collecting tubules and neck segments reacted weakly, if at all, with the PTHrP antiserum (Fig. 1e). The pattern of mRNA distribution was more diffuse with weak to moderate hybridization signal seen throughout the kidney (Table 1).

Liver, pancreas and spleen

PTHrP immunoreactivity and hybridization signal were not found in hepatocytes but were observed in the epithelium of the vessels and ducts within the liver (Table 1). PTHrP antigen and mRNA were found in the epithelium of small vessels and ducts throughout the pancreas but not in acinar cells in the pancreas (Table 1). Islet tissue was not visible in the samples studied. PTHrP immunoreactivity and hybridization signal was observed in the erythrocyte-rich regions and in the epithelium of small vessels in the spleen, but not in the lymphocyte-rich regions (Table 1).

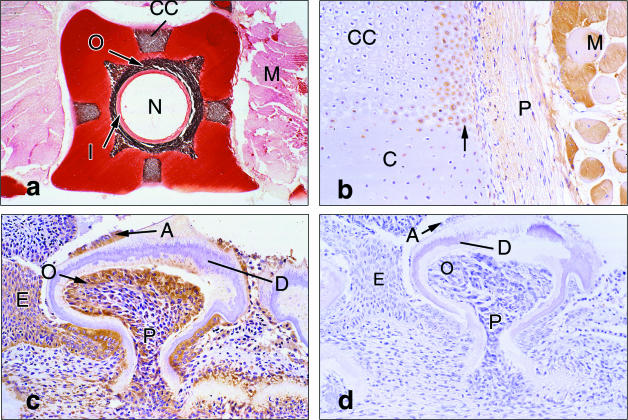

Skeletal tissues

PTHrP was observed in elasmobranch skeletal tissues, such as the notochord, vertebrae and teeth (Table 1). The elasmobranch vertebral column contains remnants of the notochord and von Kossa staining identified sites of calcification in the elasmobranch vertebral column (Fig. 2a). The elasmobranch vertebral column is composed of non-articulated biconcave vertebral bodies (centra) which are linked together by the remains of the notochord and by intervertebral cartilages (Leake, 1975). Each vertebra has a neural arch to protect the spinal column and a haemal arch that surrounds the dorsal aorta (Leake, 1975). PTHrP antigen and mRNA were present in the vacuolated cells and epithelial cells of the notochord (Table 1). PTHrP was not seen in the matrix of the elastic sheath but was observed in the cells within calcified regions of the outer notochordal sheath (Table 1). PTHrP immunoreactivity and hybridization signal were observed in chondrocytes that had not yet become incorporated into the calcified cartilage in gummy shark vertebrae and in the perichondrium (Fig. 2b). These chondrocytes, scattered throughout the uncalcified matrix close to calcifying front, contained PTHrP, but most of the chondrocytes deep within this matrix did not (Fig. 2b). PTHrP immunoreactivity was absent in the cartilage of the jaw but was observed in the epithelia and odontoblasts of developing teeth (Fig. 2c). PTHrP was not seen in the dentine of the teeth or in the underlying dermis Fig. 2(c)

Fig. 2.

(a) Von Kossa staining shows the sites of calcification (brown) in the gummy shark vertebrae. The outer notochordal sheath (O) is calcified but the inner sheath (I) is not. Vaculoated notochordal cells are not visible. Calcified cartilage (CC) occurs at the periphery of the vertebra and in association with the outer notochordal sheath. Uncalcified cartilage appears orange to red. Associated muscle (M) is visible. (×14). (b) PTHrP immunoreactivity is seen in the cytoplasm of chondrocytes (arrow) at the edge of the calcification front that lies between the calcified cartilage (CC) and perichondrium (P). Chondrocytes within the uncalcified cartilage (C) stain for PTHrP antigen, as does skeletal muscle (M). (×137.5). (c) Staining for the PTHrP antigen in the developing tooth is seen in the odontoblasts (O), and the epithelial cells (E) overlying and adjacent to the developing tooth. Some scattered cells in the pulp cavity (P) stain, but the dentine (D) does not. (×110). (d) An adjacent section stained with antiserum to PTH (1–34) shows no immunoreactivity (lettering as in 2c, ×110).

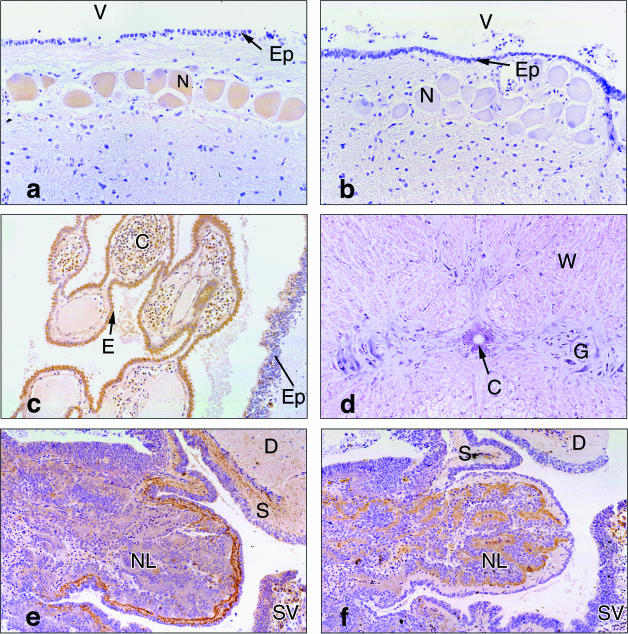

Nervous system

PTHrP immunoreactivity occurred in a number of discrete sites in the brain whereas sites of mRNA expression were more diffuse. Cerebellar Purkinje cells displayed PTHrP immunoreactivity and hybridization signal but cells in the granular and molecular layers did not (Table 1). Large neurones adjacent to the ventricle in the tectum stained for the PTHrP antigen (Fig. 3a,b) but the hybridization signal was diffuse in this region. Epithelial cells of the choroid plexus (Fig. 3c) and saccus vasculosus (an organ unique to some bony and cartilaginous fish) produced PTHrP protein and mRNA (Table 1). PTHrP antigen and mRNA were observed within grey matter of the spinal cord and in ependymal cells lining the central canal (Fig. 3d) but not in white matter (Table 1). The pre-optic area in the brain reacted differently with the N-terminal and mid-molecule PTHrP antisera. PTHrP-positive neurones were observed when a mid-molecule antibody was used but when an N-terminal antibody was substituted, the staining was diffuse, as was the hybridization signal.

Fig. 3.

(a) Immunohistochemistry shows staining in neurones (N) in the tectum that border the ventricle (V). The ventricle is lined by a layer of ependymal cells (Ep). The surrounding tissue is negative. (×110). (b) No staining of the neurones, ependymal cells lining the ventricle is seen with the PTH antiserum (lettering as in 3a, ×110). (c) Immunohistochemistry shows PTHrP antigen in epithelial cells (E) of the choroid plexus and in ependymal cells (Ep). Only scattered cells in the capillaries (C) stain for the PTHrP antigen. (×55). (d) In the spinal cord, hybridization signal for the PTHrP mRNA is seen in the grey matter (G) and, to a lesser extent, in ependymal cells lining the central canal (C). No hybridization is seen in white matter (W). (×55). (e) Angel shark pituitary incubated with mid-molecule PTHrP antiserum shows staining at the edge of the neurointermediate lobe (NL) and the stalk (S) connecting the pituitary to the diencephalon (D). Part of the saccus vasculosus (SV) is visible. (×55). (f) An adjacent section incubated with N-terminal PTHrP antiserum shows staining in the endocrine cells of the neurointermediate lobe but not in the stalk or diencephalon. Part of the saccus vasculosus is visible (lettering as in 3e, ×55

Pituitary

The elasmobranch pituitary demonstrated differential staining with the N-terminal and mid-molecule PTHrP antibodies. These differences appeared to be independent of the sex and species of the animal. Mid-molecule PTHrP immunoreactivity was detected in the nervous tissue between endocrine cells of neurointermediate lobe (pars intermedia and pars nervosa) and in discrete sites within the infundibulum (Fig. 3e). N-terminal PTHrP immunoreactivity occurred in the endocrine cells defined as such by their histology and anatomical relationship, of the neurointermediate lobe and pars distalis (Fig. 3f). Hybridization signal was observed in the pars distalis and the pars intermedia (Table 1).

Discussion

Data from this study demonstrate that PTHrP is widely distributed among elasmobranchs. It extends the evolutionary history of PTHrP past teleosts where there has been the identification of a receptor that recognizes human PTHrP (Rubin & Jüppner, 1999) and the isolation and analysis of the fish (Fugu rubripes) PTHrP gene (Power et al. 2001). The presence of PTHrP in bony fish may not be relevant to its localization in elasmobranchs, as there is some controversy about the evolution of these two groups. Some researchers suggest that elasmobranchs arose from a common stock that gave rise to the Chondrichthyes and the bony fish (Compagno, 1977; Schaeffer & Williams, 1977) but others suggest that they arose from a different stock to the bony fishes (Gilbert, 1993).

The presence of PTHrP antigen and mRNA in sites such as the gill, kidney and rectal gland suggests involvement in osmoregulation. PTHrP antigen and mRNA was located in the intraepithelial lamellae as well as in the crypt or ‘chloride’ cells. The gill interlamellar epithelium in teleosts has roles in osmoregulation and chloride cells have been identified in the interlamellar epithelium in elasmobranchs (for review see Evans, 1993) b3ut their numbers are lower than those seen in teleosts (Bone et al. 1995). However, there is no direct evidence that these cells function in salt secretion in elasmobranchs (Evans, 1979) and the branchial Na+/K+-ATPase activity is low. If new data do provide evidence that the gill epithelium participates in iono- or osmo-regulation in elasmobranchs, it is possible that PTHrP could be involved in this process. This would be consistent with its localization to sites that are known to participate in osmoregulation, such as the kidney and rectal gland.

PTHrP increases phosphate excretion and restricts calcium excretion in the mammalian kidney (Ebeling et al. 1989; Rizzoli et al. 1989; Zhou et al. 1989). The sites of PTHrP localization in the elasmobranch kidney suggest that PTHrP may be a regulator of sodium and phosphate transport, and possibly of other ions and urea. The kidney in elasmobranchs regulates salt, urea and water balance (Henderson et al. 1986), and maintains the plasma of the shark hyperosmotic to seawater. Marine elasmobranchs maintain high concentrations of urea and trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) in the plasma so that blood osmolarity is close to that of seawater (review: Pang et al. 1977), and as a result, suffer little osmotic loss of water. The kidney tubules in elasmobranchs regulate the excretion of sodium and chloride and divalent ions and reabsorption of urea and TMAO (Hickman & Trump, 1969; Pang et al. 1977). PTHrP increases phosphate excretion in perfused rat kidneys (Ebeling et al. 1989) and may affect sodium-dependent phosphate transport (Pizurki et al. 1988) and regulate sodium transport (Caverzasio et al. 1988) in opossum kidney cells. Studies of the effects of PTHrP on the elasmobranch kidney would be necessary to determine whether it has similar effects in the kidney of lower vertebrates.

The rectal gland is unique to elasmobranchs. (Evans, 1993). The rectal gland acts as a site of extrarenal secretion of excess NaCl in marine elasmobranchs and involves an Na/Cl co-transport system (for a review, see Evans, 1993). This transport system is in turn dependent upon the Na/K exchange driven by the Na+/K+-ATPase which is found in this gland (Evans, 1993). Similarities exist in the NaCl transport system in the rectal gland with that found in the loop of Henle (thick ascending limb) in the mammalian kidney. As the rectal gland represents a novel site of PTHrP distribution within vertebrates, it may be that it has some as yet undefined roles in this organ.

Results from the current study indicate that the pattern of distribution of PTHrP in the elasmobranch rectal gland and gill is conserved between different families of elasmobranchs. Physiological investigation is required to determine whether PTHrP has novel roles in the gill epithelium. Fugu rubripes N-terminus PTHrP was found to have a stimulatory action on calcium uptake in sea bream larvae implying that PTHrP might be a hypercalcaemic factor in teleosts (Guerreiro et al. 2001). They hypothesized that PTHrP might act on the gill chloride cells and the intestinal epithelium probably through specific receptors. Whether PTHrP acts in this manner in elasmobranchs cannot be investigated until elasmobranch PTHrP has been isolated and its homology with teleost PTHrP determined.

The results of the current study, together with previous work on dogfish (Ingleton et al. 1995), suggest that PTHrP has a generalized distribution in the epithelium forming the choroid plexus and saccus vasculosus of elasmobranchs. The demonstration of PTH/PTHrP receptors in these epithelia in the red stingray (Akino et al. 1998) suggests that PTHrP may be physiologically active in these tissues. It has been proposed that the epithelium of the choroid plexus is secretory and involved in the regulation of ion gradients between the cerebrospinal fluid and the blood (Cserr, 1971; Cserr & Bundgaard, 1984). The saccus vasculosus, a tissue unique to some bony and cartilaginous fish, may also represent a transporting epithelium involved in osmoregulation (Jansen et al. 1981, 1982). PTHrP is secreted by the saccus vasculosus in bony fish (Devlin et al. 1995). Ingleton et al. (1995) proposed that epithelial cells in the saccus vasculosus and the choroid plexus may be a source of factors, such as PTHrP, secreted into the cerebrospinal fluid, or provide a system for transporting neuronal products from the cerebrospinal fluid into the circulation. Distribution data for PTHrP mRNA from the current study suggest that the immunoreactive PTHrP in these sites is produced in situ

The Chondrichthyes are characterized by an internal skeleton composed of cartilage (Compagno, 1977; Schaeffer & Williams, 1977), parts of which may calcify. Although bone appears to be absent in modern elasmobranchs, it was probably present in ancestral cartilaginous fish (Clement, 1992). Histological data suggest that the formation of the mineralized cartilaginous skeleton in elasmobranchs mimics the early stages of endochondral ossification in mammals (Clement, 1992). The presence of PTHrP in chondrocytes outside the calcification zone in shark vertebrae resembles its appearance in chondrocytes during early endochondral bone formation in mammals (Lee et al. 1995). The absence of PTHrP in chondrocytes embedded in calcified cartilage, and those deep within uncalcified matrix, is similar to data demonstrating that osteocytes deep within mammalian bone matrix are not PTHrP immunoreactive (Kartsogiannis et al. 1997). PTHrP has a central role in mammalian skeletal development through modulation of chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation (Wysolmerski & Stewart, 1998) and this role may have been conserved during vertebrate evolution. The similarity between the distribution of PTHrP in the elasmobranch skeleton and that in the developing mammalian skeleton is consistent with the idea that bone existed in ancestral elasmobranchs. The demonstration of PTHrP within the notochord may reflect an early evolutionary association of PTHrP with vertebrate skeletal elements. The functions that PTHrP has in the growth of the elasmobranch skeleton remain to be investigated.

Differences in staining patterns between N-terminal and mid-molecule PTHrP antisera in the elasmobranch pituitary and pre-optic nucleus suggest that post-translational processing of the PTHrP molecule may occur in these sites. The pre-optic nucleus is found in all fishes and amphibians and is regarded as the homologue of supra-optic and paraventricular nuclei of amniotes (Holmes & Ball, 1974). Differences in staining between antiserum to N-terminal PTHrP(1–16) and C-terminal PTHrP(107–111) were observed in the flounder pituitary (Danks et al. 1998) and these data support the idea of post-translational processing of PTHrP in fish. Post-translational processing of the PTHrP molecule in mammals yields a family of biologically active peptides (Philbrick et al. 1996). The pars distalis of the elasmobranch pituitary displayed N-terminal PTHrP immunoreactivity, which is consistent with observations from the dogfish (Ingleton et al. 1995) and the sea bream (Danks et al. 1993), suggesting that N-terminal PTHrP released from the fish pituitary may act as a classical hormone. Another possibility is PTHrP in the pars distalis could regulate other pituitary hormones, such as prolactin or growth hormone, via autocrine or paracrine pathways.

The distribution of PTHrP mRNA shown in this study indicates that the immunoreactive PTHrP observed in these tissues is produced in situ. Although immunoreactive PTHrP was not found in the dogfish gill (Ingleton et al. 1995), the demonstration of PTHrP in the gills of elasmobranchs from six families suggests that it occurs widely in the elasmobranchs. Additionally, PTHrP has been demonstrated in the bony fish gill (Danks et al. 1998). It is possible that PTHrP in sites such as the gill, rectal gland and saccus vasculosus, tissues not found in higher vertebrates, will perform tasks not yet revealed by studies in mammals.

The occurrence of PTHrP in elasmobranch tissues such as skin, muscle, kidney, spleen, teeth and brain mirrors the production sites in mammals (Ingleton & Danks, 1996; Philbrick et al. 1996) and amphibians (Danks et al. 1997), and this suggests that the sites of PTHrP production have been conserved in the vertebrates. It is therefore possible that functions such as the modulation of differentiation and proliferation that are associated with these mammalian tissues may also be present in submammalian vertebrates such as elasmobranchs. In addition, it is possible that the distribution of PTHrP will vary during development in elasmobranchs as it does in mammals. The absence of PTHrP in the adult elasmobranch liver parallels a similar absence in mammals, so examination of embryonic elasmobranchs may demonstrate that PTHrP is produced by fetal hepatocytes, as it is in fetal mammals (Ingleton & Danks, 1996; Philbrick et al. 1996).

This study demonstrated widespread distribution of PTHrP antigen and mRNA in cartilaginous fish including phylogenetically ancient species such as the Port Jackson shark. The tissue distribution of PTHrP in this group of vertebrates showed some similarity to the tissue distribution in higher vertebrates. The pattern of PTHrP distribution in the shark vertebra was of particular interest, as it resembled the pattern of PTHrP distribution observed during early endochondral bone formation in mammals. The widespread distribution of PTHrP in lower vertebrates such as elasmobranchs suggests that it may have a similar variety of physiological roles as it does in mammals. Since PTHrP was also found in tissues that are not present in higher vertebrates it may also be found to serve novel functions in these tissues.

Acknowledgments

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia, supported this research. We are grateful to Dr Patricia Ingleton for her generous assistance with organ collection and identification. David Paul (Department of Zoology) kindly helped with the photomicrography and production of the figures. Lauren Brown and Natalie Bridge (Marine and Freshwater Resources Institute) assisted with the collection of elasmobranch tissues.

References

- Akino K, Ohtsuru A, Nakashima M, Ito M, Ting-Ting Y, Braiden V, et al. Distribution of the parathyroid hormone-related peptide and its receptor in the saccus vasculosus and choroid plexus in the red stingray. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1998;18:362–368. doi: 10.1023/A:1022509300758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft JD, Stevens A. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bone Q, Marshall NB, Blaxter JHS. Biology of Fishes. Glasgow: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Caverzasio J, Rizzoli R, Martin TJ, Bonjour JP. Tumoral synthetic parathyroid hormone-related peptide inhibits amiloride sensitive transport in cultured renal epithelia. Pflugers Arch. 1988;413:96–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00581235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chailleux N, Milet C, Vidal A, Lopez E. Presence of PTH-like and PTH-related peptide-like molecules in submammalian vertebrates. Neth. J. Zool. 1995;45:248–250. [Google Scholar]

- Clement JG. Re-examination of the fine structure of endoskeletal mineralization in chondrichthyans: implications for growth, ageing and calcium homeostasis. Aust. J. Mar. Freswater Res. 1992;43:157–181. [Google Scholar]

- Compagno L. Phyletic relationships of living sharks and rays. Am. Zool. 1977;17:303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cserr HF. Physiology of the choroid plexus. Physiol. Rev. 1971;51:273–311. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1971.51.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserr HF, Bundgaard M. Blood–brain interfaces in vertebrates: a comparative approach. Am. J. physiol. 1984;246:R277–R288. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.3.R277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danks JA, Ebeling PR, Hayman J, Chou ST, Moseley JM, Dunlop J, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: immunohistochemical localization in cancers and in normal skin. J. Bone. Miner. Res. 1989;4:273–278. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danks JA, Devlin AJ, Ho PMW, Diefenbach-Jagger H, Power DM, Canario A, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein is a factor in normal fish pituitary. General Comp. Endocrinol. 1993;92:201–212. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1993.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danks JA, McHale JC, Martin TJ, Ingleton PM. Parathyroid hormone-related protein in tissues of the emerging frog (Rana temporaria) immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridisation. J. Anat. 1997;190:229–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19020229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danks JA, Hubbard PC, Balment RC, Ingleton PM, Martin TJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein localization in tissues of freshwater and saltwater-acclimatized flounder. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;839:503–505. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin AJ, Danks JA, Faulkner MK, Power DM, Canario AVM, Martin TJ, et al. Immunochemical detection of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the saccus vasculosus of a teleost fish. General Comp. Endocrinol. 1995;101:83–90. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1996.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeling PR, Adam WR, Moseley JM, Martin TJ. Actions of synthetic parathyroid hormone-related protein (1–34) on the isolated rat kidney. J. Endocrinol. 1989;120:45–50. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1200045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DH. Osmotic and ionic regulation. In: Evans DH, editor. In: The Physiology of Fishes. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CR. Evolution and Phylogeny. In: Evans DH, editor. In: The Physiology of Fishes. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro PM, Fuentes J, Power DM, Ingleton PM, Flik G, Canario AVM. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: a calcium regulatory factor in sea bream (Sparus auarata L) larvae. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;281:R855–R860. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.3.R855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey S, Zeng YY, Pang PKT. Parathyroid hormone-like immunoreactivity in fish plasma and tissues. General Comp. Endocrinol. 1987;68:136–146. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(87)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IW, O'Toole LB, Hazon N. Kidney function. In: Shuttleworth TJ, editor. Physiology of Elasmobranch Fish. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman CPJ, Trump BF. The kidney. In: Fish Physiology. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, editors. London: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 91–240. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes RL, Ball JN. London: Cambridge University Press; 1974. The Pituitary Gland. A Comparative Account. [Google Scholar]

- Ingleton PM, Hazon N, Ho PMW, Martin TJ, Danks JA. Immunodetection of parathyroid hormone-related protein in plasma and tissues of an elasmobranch (Scyliorhinus canicula) Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1995;98:211–218. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1995.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingleton PM, Danks JA. Distribution and functions of parathyroid hormone-related protein in vertebrate cells. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1996;166:231–280. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen WF, Flight WF, Zandbergen MA. Fine structural localization of adenosine triphosphatase activities in the saccus vasculosus of the rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri Richardson. Cell Tiss. Res. 1981;219:267–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00210147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen JW, Burger EH, Zandbergen MA. Subcellular localization of calcium in the coronet cells and tanycytes of the saccus vasculosus of the rainbow troutSalmo gairdneri Richardson. Cell Tiss. Res. 1982;224:169–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00217276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jüppner H, Abou Samra AB, Freeman M, Kong XF, Schipani E, Richards J, et al. A G protein-linked receptor for parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Science. 1991;254:1024–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.1658941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Pang PKT. Immunocytochemical detection of parathyroid hormone-like substance in the goldfish brain and pituitary. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1987;68:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(87)90070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartsogiannis V, Moseley J, McKelvie B, Chou ST, Hards DK, Ng KW, et al. Temporal expression of PTHrP during endochondral bone formation in mouse and intramembranous bone formation in an in vivo rabbit model. Bone. 1997;21:385–392. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kracier J, Herlant M, Duclos P. Changes in adenohypophyseal cytology and nuclei acid content in the rat 32 days after bilateral adrenalectomy and the chronic injection of cortisol. Can. J. Physiol. 1967;45:947–956. doi: 10.1139/y67-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake LD. London: Academic Press; 1975. Comparative Histology: an Introduction to the Microscopic Structure of Animals. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KC, Deeds JD, Segre GV. Expression of parathyroid hormone-related peptide and its receptor messenger ribonucleic acids during fetal development of rats. Endocrinology. 1995;136:453–463. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.2.7835276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Moseley JM, Williams ED. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: hormone and cytokine. J. Endocrinol. 1997;154:S23–S37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley JM, Kubota M, Diefenbach-Jagger H, Wettenhall REH, Kemp BE, Suva LJ, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein purified from a human lung cancer cell-line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:5048–5052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang PKT, Griffith RW, Atz JW. Osmoregulation in elasmobranchs. Am. Zool. 1977;17:365–377. [Google Scholar]

- Philbrick WM, Wysolmerski JJ, Galbraith S, Holt E, Orloff JJ, Yang KH, et al. Defining the roles of parathyroid hormone-related protein in normal physiology. Physiol. Rev. 1996;76:127–173. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizurki L, Rizzoli R, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, Caverzasio J, Bonjour JP. Effect of synthetic tumoral PTH-related peptide on cAMP production and Na-dependent Pi transport. Am. J. Physiol. 1988;255:F957–F961. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.5.F957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power DM, Ingleton PM, Flanagan J, Canario AVM, Danks J, Elgar G, et al. Genomic structure and expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) in a teleost, Fugu rubripes. Gene. 2001;250:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoli R, Caverzasio J, Chapuy MC, Martin TJ, Bonjour JP. Role of bone and kidney in parathyroid hormone-related peptide-induced hypercalcemia in rats. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1989;4:759–765. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DA, Jüppner H. Molecular cloning of a zebrafish cDNA encoding a novel parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related protein (PTHrP) receptor (PPR) In: Danks J, Dacke C, Flik G, Gay C, editors. Calcium Metabolism: Comparative Endocrinology. Bristol: BioScientifica; 1999. pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer B, Williams M. Relationships of fossil and living elasmobranchs. Am. Zool. 1977;17:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Schermer DT, Chan SD, Bruce R, Nissenson RA, Wood WI, Strewler GJ. Chicken parathyroid hormone-related protein and its expression during embryonic development. J. bone miner. Res. 1991;6:149–155. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberger LA, Hardy PH, Cuculus JJ, Meyer HG. The unlabelled antibody enzyme method of immunohistochemistry: preparation and properties of soluble antigen-antibody complex (horseradish peroxidase-antihorseradish peroxidase) and its use in identification of spirochetes. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1970;18:315–333. doi: 10.1177/18.5.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suva LJ, Winslow GA, Wettenhall REH, Hammonds RG, Moseley JM, Diefenbach-Jagger H, et al. A parathyroid hormone-related protein implicated in malignant hypercalcemia: cloning and expression. Science. 1987;237:893–896. doi: 10.1126/science.3616618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysolmerski JJ, Stewart AF. The physiology of parathyroid hormone-related protein: an emerging role as a developmental factor. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1998;60:431–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Choong PFM, McCarthy R, Chou ST, Martin TJ, Ng KW. In situ hybridization to show sequential expression of osteoblast gene markers during bone formation in vivo. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1994;9:1489–1499. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Leaver DD, Moseley JM, Kemp B, Ebeling PR, Martin TJ. Actions of parathyroid hormone-related protein on the rat kidney in vivo. J. Endocrinol. 1989;122:229–235. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1220229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]