Abstract

The lymphoid tissues of the metatherian mammal, the adult tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii, were investigated using immunohistochemical techniques. Five cross-reactive antibodies previously shown to recognize surface markers in marsupial tissues and five previously untested antibodies were used. The distribution of T-cells in the tissue beds of spleen, lymph node, thymus, gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) was documented using antibodies to CD3 and CD5. Similarly, B-cells were identified in the same tissues using anti-CD79b. Antibodies to CD8, CD31, CD79a and CD68 failed to recognize cells in these tissue beds. In general the pattern of cellular distribution identified using these antibodies was similar to that observed in other marsupial and eutherian lymphoid tissues. This study provides further information on the commonality of lymphoid tissue structure in the two major groups of extant mammals, metatherians and eutherians.

Keywords: immunohistochemistry, lymphoid tissue, marsupial, tammar wallaby

Introduction

As a first step in understanding the marsupial or metatherian immune system, the cellular composition of the lymphoid tissues must be investigated. Traditionally, studies on the structure of these lymphoid tissues have been limited to using standard histological techniques, due to a lack of tools for specific identification of cell types. However, within the last decade some species cross-reactive antibodies to the lymphoid cell surface markers CD3, CD5, CD79a and CD79b have been developed that are able to recognize T- and B-cells in a diverse array of eutherian and metatherian species (Jones et al. 1993). They have been shown to react with surface markers of lymphoid cells of the adult brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula), adult ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus peregrinus), adult tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii), koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) (Hemsley et al. 1995), Brazilian white bellied opossum (Didelphis albiventris) (Coutinho et al. 1995) and the grey short tail opossum (Monodelphis domestica) (Jones et al. 1993). Recently, they have also been shown to react with tissues from the northern brown bandicoot (Isoodon macrourus) (Cisternas & Armati, 2000; Old & Deane, 2002), pouch young brushtail possums (Baker et al. 1999) and the eastern grey kangaroo (Old & Deane, 2001).

In this study, new antibodies developed to the conserved regions of a number of lymphoid cell surface markers, including CD8, CD31 and CD68, were assessed for their capacity to recognize marsupial cells. In addition, two other antibodies developed to recognize marsupial-specific sequences of the T-cell receptor (TCR) α chain and the J-chain of secretory immunoglobulin were tested. All antibodies were assessed for their capacity to recognize cells in the lymphoid tissues of the tammar wallaby using the immunohistochemical technique of cell-specific visualization.

Materials and methods

Animals and sample collection and preparation

Fresh tissue was collected opportunistically from 13 adult females and one juvenile female tammar wallaby, which had been killed as part of approved reproductive studies at Macquarie University, NSW, Australia. Tissues, including cervical and thoracic thymus, spleen, lymph nodes, intestine and lungs, were dissected and immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. After fixation, tissues were routinely processed using graded alcohol steps, cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin wax. Eutherian tissue samples, including a human tonsil donated by Westmead Hospital and a rat spleen, were used as controls and processed according to the same protocols.

Primary antibodies

Primary monoclonal antibodies to CD3, CD5, CD79b and CD79b raised against synthetic human peptide sequences were kindly donated by Dr Margaret Jones of the Immunodiagnostics Unit, Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK. Anti-brushtail possum J-chain was kindly donated by Dr Fran Adamski, Ag Research, New Zealand. This monoclonal antibody was raised against a synthesized peptide based on the cloned brushtail possum J-chain cDNA sequence (Adamski & Demmer, 2000). Similarly, using an epitope sequence derived from the partial cDNA sequence in the tammar wallaby for the TCRα molecule (Zuccolotto et al. 2000) an antibody directed at the marsupial TCR was produced. Peptide synthesis, conjugation with carrier protein and preparation of the antibody was undertaken by Alpha Diagnostic International (ADI) (San Antonio, TX, USA). Polyclonal antibodies to CD3 were purchased from DAKO Corporation (Carpenteria, CA, USA). Table 1 gives the eutherian equivalent/target cell, and epitope sequences for these antibodies.

Table 1.

Epitopes and tissues used to raise and test antibodies to CD3, CD5, CD8, CD31, CD68, TCRα, J Chain, CD79a and CD79b

| Antibody | Eutherian equivalent/target cell | Epitope sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| monoclonal and polyclonal anti-CD3ɛ | CD3ɛ chain of the CD3 complex on T-cells | ERP PPV PNP DYE PC | Jones et al. (1993)) |

| monoclonal anti-CD5 | T-cells and some B-cells | SSM QPD NSS DSD YDL HGA QRL | Jones et al. (1993) |

| monoclonal anti-CD8α | T-cytotoxic and T-suppressor cells | KSG NKP SLS ARY V | Mason et al. (1992) |

| monoclonal anti-CD31 | Endothelial cells | Membrane extract from a spleen affected by hairy cell leukaemia | Parums et al. (1990) |

| monoclonal anti-CD68 | Macrophages and monocytes | Lysosomal fraction from human lung macrophages | Hameed et al. (1994) |

| monoclonal anti-CD79a | B-cells expressing mb-1 (part of the B-cell receptor complex) | GTY QDV GSL NIA DVQ | Jones et al. (1993) |

| monoclonal anti-CD79b | B-cells expressing B29 (part of the B-cell receptor complex) | GQV KWS VGE HPG QE | Jones et al. (1993) |

| monoclonal anti-J-chain | Cells expressing J-chain (and IgA or IgM) | Recombinant peptide based on a fragment of the brushtail possum J-chain cDNA sequence | Adamski & Demmer (2000) |

| polyclonal anti-TCRα | Extracellular portion of the TCRα chain | EDG YKG ATC KVQ DVQ QSF ET |

Histology and immunohistochemistry

For both histological and immunohistological studies, 4-µm sections were cut and placed on precoated 3-aminotriethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) slides. For histological studies, sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (Bancroft & Stevens, 1982).

For immunohistochemistry, all slides were routinely dewaxed in xylene and hydrated in graded alcohol steps before a final treatment for 5 min in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in 1 : 1 methanol and PBS for 30 min followed by a wash in PBS for 5 min. The sections were then microwaved on high (800 W) in Vector Antigen Retrieval Solution (Vectorlabs, CA, USA) for 20 min to expose the target antigens. The sections were left in this solution until tepid (approximately 20 min) and were then washed in PBS for 5 min to remove all traces of the retrieval solution. Prior to addition of primary antibody, non-specific antibody binding was reduced by the addition of a 1 : 20 dilution of horse serum in PBS for 20 min. Serum was then removed and optimized dilutions of primary antibody in PBS were added to the sections before incubation at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, all unbound antibody was removed by washing with PBS for 5 min. The range of antibody dilutions tested is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibodies tested in this study, their source and the tissues and dilutions tested

| Antibody | Marsupial tissues tested | Dilutions tested |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal anti-CD3 | All tissues | Undiluted, 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20, 1 : 50 and 1 : 100 |

| Polyclonal anti-CD3 | All tissues | 1 : 100, 1 : 200, 1 : 500, 1 : 1000 and 1 : 2000 |

| Monoclonal anti-CD5 | All tissues | Undiluted, 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20, 1 : 50 and 1 : 100 |

| Monoclonal anti-CD8 | Spleen and lymph node | Undiluted, 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20 and 1 : 50 |

| Monoclonal anti-CD31 | Spleen and lymph node | Undiluted, 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20 and 1 : 50 |

| Monoclonal anti-CD68 | Spleen and lymph node | Undiluted, 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20 and 1 : 50 |

| Monoclonal anti-CD79a | All tissues | Undiluted, 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20 and 1 : 50 |

| Monoclonal anti-CD79b | All tissues | 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20,1 : 50, 1 : 100, 1 : 200, 1 : 500 and 1 : 1000 |

| Polyclonal anti-J-chain | Spleen and lymph node | 1 : 10, 1 : 100, 1 : 500, 1 : 1000, 1 : 2000, 1 : 5000 and 1 : 100 000 |

| Polyclonal anti-TCRα | Spleen and lymph node | 1 : 10, 1 : 100, 1 : 500, 1 : 1000 |

Immunohistochemical staining was undertaken using a Vectorstain Universal Elite kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The chromagen, Sigmafast DAB (3′,3′-diaminobenzidine) (Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with the tissue sections in the dark at room temperature for 5 min to visualize the antibody complex. The reaction was terminated with a water wash before being counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and coverslipped using Entellan (Merck and Company, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA).

Positive and negative controls were undertaken to identify any non-specific staining. Human tonsil or rat spleen samples were used as positive control tissues. For negative controls, the primary antibody was replaced by normal mouse IgG1 (Sigma-Aldrich), IgG2b (Sigma-Aldrich) or pre-immune serum (Sigma-Aldrich) from the same species as that of the primary antibody. Similarly, in the secondary antibody control, the secondary antibody was replaced with non-immune horse serum. In some cases, the secondary antibody was replaced with PBS.

All slides were viewed using an Olympus CX40RF200 microscope and digital images obtained using a Leica DMR DAS light microscope connected to an IBM compatible computer and Zeiss Axiovision software.

Results

Determination of antibody reactivity

All primary antibodies were initially tested on tammar spleen and lymph node samples at a range of concentrations and incubation times (Table 2). Antibodies to CD8, CD31, CD68 and CD79a failed to recognize any cells under the test conditions. In contrast, antibodies to the brushtail possum J-chain resulted in non-specific staining whilst the pre-immune serum did not stain any cells. Conditions were optimized such that antibodies to CD3, CD5, CD79b and TCRα reacted with cells in the test spleen and lymph node samples with no reaction observed using any of the primary antibody negative controls.

Tammar lymphoid tissues

Anti-CD3, anti-CD5, anti-CD79b and anti TCRα antibodies were subsequently used to determine the cellular distributions of the expressed surface molecules in lymphoid tissues.

Thymus

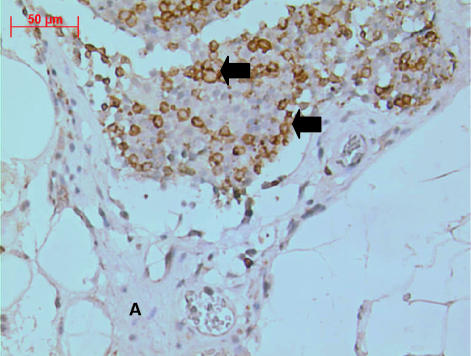

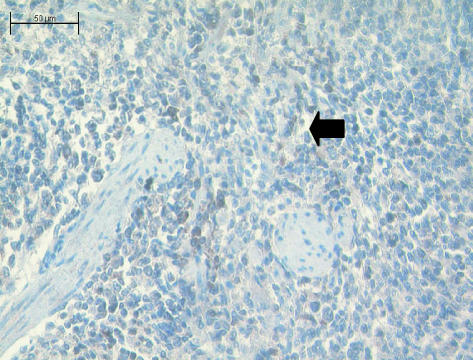

Twelve cervical and thoracic thymus samples were assessed. Antibodies to CD3 (Fig. 1) and CD5 (data not shown) stained most lymphocytes and thymocytes in the tissue beds. Large areas of adipose surrounded the lymphocyte islands in both tissues. An occasional CD79b+ cell was stained (data not shown), whilst anti-TCRα stained a limited number of cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Adult tammar wallaby cervical thymus stained with polyclonal anti-CD3, showing lymphocyte islands surrounded by large amounts of connective tissue and adipose (A). Most cells are CD3+ T-cells (arrows). Some lymphocyte-like cells were not stained by anti-CD3. ×400.

Fig. 2. Thoracic thymus of the adult tammar wallaby stained with anti-TCRα. Large numbers of stained TCRα+ cells (arrow) are seen. ×100.

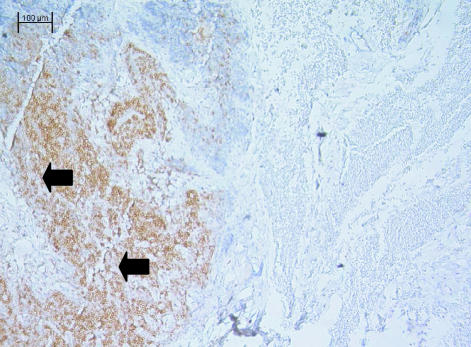

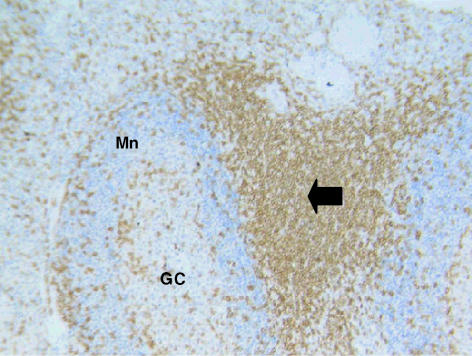

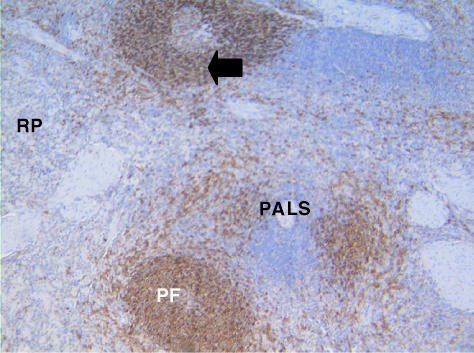

Spleen

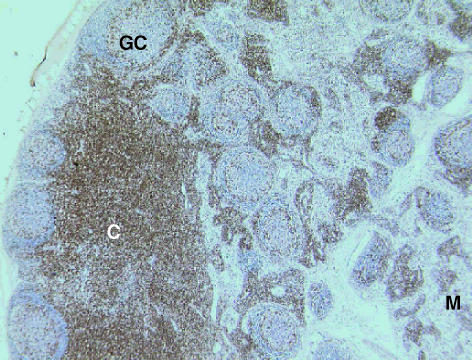

Antibodies to CD3 (data not shown) and CD5 (Fig. 3) heavily stained lymphocytes in the cortical areas of the spleen. A few cells were also stained in the periphery of the germinal centre of secondary follicles. Anti-CD79b (Fig. 4) recognized cells in the B-cell areas of the tammar wallaby lymph nodes. Cells were heavily stained in the mantles of secondary follicles and throughout primary follicles as well as a few in the medullary cords and sinuses. No CD79b-positive cells were stained in the cortical regions. TCRα-positive lymphocytes were detected in the T-cell areas of the spleen (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3. Spleen of the tammar wallaby stained with anti-CD5 antibodies. Lymphocytes are stained heavily in the T-cell areas (arrow). The pattern of staining is similar in distribution to that observed using anti-CD3 (data not shown). The mantle (Mn) and germinal centre (GC) are also lightly stained. ×100.

Fig. 4. Spleen of the tammar wallaby stained with anti-CD79b antibodies. Large numbers of lymphocytes are stained in the primary follicles (PF) and mantles of secondary follicles (arrow). Positive staining cells are also present throughout the red pulp (RP) areas. The peri-arterial lymphatic areas (PALS) are unstained. ×100.

Fig. 5. Spleen of the tammar wallaby stained with anti-TCRα antibodies. TCRα+ cells (arrow) are apparent in the T-cell areas. ×100.

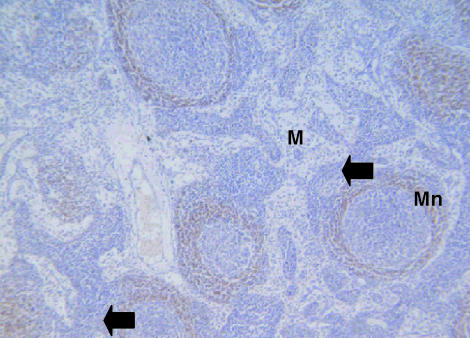

Lymph nodes

CD3-positive (Fig. 6) and CD5-positive (no data shown) cells were observed in the paracortical regions of the lymph nodes as were a few rare cells in the outer regions of the germinal centres, mantle zones and medullary cords and sinuses. Anti-CD79b antibodies (Fig. 7) stained cells in the mantle zones of the secondary follicles and a few cells in the medullary cords and sinuses.

Fig. 6. Lymph node of the tammar wallaby stained with anti-CD3 antibody. CD3+ stained lymphocytes are present throughout the paracortical areas (C). Some cells are also stained in the medulla (M) although much fewer in number. The majority of cells in the germinal centres (GC) are unstained. ×40.

Fig. 7. Lymph node of the tammar wallaby stained with anti-CD79b antibody. CD79b+ stained lymphocytes are present in the medulla (M) and the mantle (Mn) regions of lymph nodes. ×100.

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT)

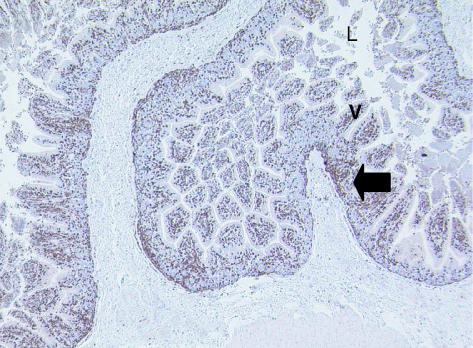

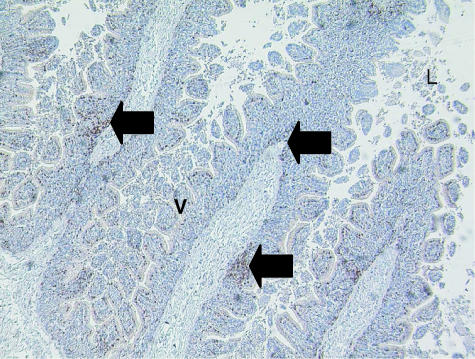

Eight adult tammar wallabies were assessed for GALT. Anti-CD3 antibodies heavily stained cells throughout the entire length of the intestinal villi (Fig. 8). Cells appeared more densely stained in some areas compared to others. Fewer CD5-positive cells were observed compared to those detected with anti-CD3 antibodies but nonetheless many cells still stained positive (Fig. 9). Small accumulations of cells were more obvious using this antibody compared to staining with anti-CD3. Accumulations of cells were present at the base of the villi with the majority of the single stained cells present at the villous tip. Fewer cells were stained in the middle of the villous projection.

Fig. 8. Adult tammar wallaby GALT showing CD3-positive T-cells (arrow) amongst the villi (V), present in large numbers. The lumen (L) can also be clearly observed. ×100.

Fig. 9. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue of the tammar wallaby stained with anti-CD5 antibodies. CD5+ stained cells are not as prevalent as those observed in the previous figure stained with anti-CD3. However, there are some cells stained in the villi (V) of the intestine. A few areas seem to have small accumulations of CD5+ cells (arrows). No cells stained within the lacteals of the villi. The lumen (L) is clearly identifiable. ×100.

Only scattered cells throughout the villi were stained by anti-CD79b antibody (data not shown).

Lungs and bronchus-associated lymphoid tissues (BALT)

No defined BALT was observed in any of the 11 lung samples investigated from adult tammar wallabies. Rare T-cells were detected amongst the cells lining the alveoli and occasional cells were also stained within the blood vessels of the lungs using anti-CD3 and anti-CD5 antibodies (data not shown). Similarly, rare CD79b+ cells were also observed amongst the alveoli lining cells and occasionally within the blood vessels (data not shown).

Discussion

Antibody reactivity

The tammar wallaby is probably one of the most studied macropod species in Australia and has been viewed as a model marsupial, mainly due to their successful breeding in captivity and hence availability for scientific study. This study has sought to provide more fundamental information on the structure of the lymphoid tissues in this animal.

A reliable and consistent immunohistochemistry technique has been developed to test the reactivity of all the antibodies in this study. Human tonsil and rat spleen sections were used as positive control slides during initial optimization to ensure the antibodies and kits were working as specified. After confirmation that the techniques worked on these tissues they were used as controls and subsequently tests on tammar wallaby tissues were conducted.

Anti-CD8

A number of antibodies tested in this study, specifically anti-CD8, anti-CD31 and anti-CD68, failed to react with tammar wallaby spleen and lymph node samples and were not tested on any other tissues. This lack of reactivity was presumably due to a lack of commonality in the antigenic sequence used to develop the test antibody. Anti-CD8 was prepared against a 13 amino acid long peptide sequence from the C terminal region of the human CD8α chain (Mason et al. 1992). In eutherian mammals, such as humans, CD8 is a cytotoxic/suppressor T-cell marker and is also expressed by the majority of human thymocytes, some γ/δ T-cells and natural killer cells (Mason et al. 1992). Currently, it is suspected that marsupials have a similar array of T-cell subsets as eutherians but, to date, this has not been proven. Attempts to isolate and sequence the CD8α chain cDNA in the tammar wallaby have been unsuccessful (unpublished data). It was difficult to identify conserved areas of the eutherian CD8α chain cDNA sequences in which to select primer sites. Presumably this would be reflected in even less conservation of the protein sequences for the CD8α and β chains and hence may explain the lack of crossreactivity of this antibody.

Anti-CD31

The antibody directed against human CD31 (a vascular cell adhesion molecule) also failed to react with tammar wallaby tissues despite obvious vascular elements in both the spleen and lymph node samples. Garcia-Porrero et al. (1998) found anti-CD31 (clone JC70) only cross-reacted with mouse fetal liver endothelial and endothelial-like cells. This may also be the case in the tammar wallaby but liver tissue was not examined. In human peripheral blood cell smears the antibody stains neutrophils, 50% of lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets, and plasma cells and megakaryocytes in bone marrow, whilst in human cryostat sections, the antibody stains endothelial cells and weakly stains some mantle zone T- and B-cells (Parums et al. 1990). It is likely that the CD31 molecule in humans and mice is significantly different to tammar wallaby CD31 and hence fails to recognize such cells in tammar wallaby tissue samples. Alternatively, fresh blood smears or frozen sections rather than routinely processed tissues may need to be used for cross-reactivity to be apparent.

Anti-CD68

Anti-CD68 (clone KP1) is directed at an intracytoplasmic molecule associated with lysosomal granules (Hameed et al. 1994). This molecule has been suggested to play a role in the generation of oxygen radicals during respiratory burst in phagocytosing cells (Weiss et al. 1994). In formalin-fixed tissues it recognizes macrophages and occasional mast cells (Hameed et al. 1994). Armstrong & Ferguson (1997) found that anti-CD68 (KP1 clone) did not cross-react with the grey short tail opossum and as it fails to cross-react with the tammar wallaby spleen and lymph nodes as well as with spleens and lymph nodes from cats, dogs, goats, pigs, cows and horses, but does cross-react with monkey macrophages (Zeng et al. 1996); this suggests that KP1 may only react with primate macrophages.

Anti-CD79a

In this study monoclonal anti-CD79a failed to react with tammar wallaby tissues and this is consistent with Hemsley et al. (1995) who found that monoclonal anti-CD79a only stained scattered lymphoid cells in brushtail possum tissues but not those of the koala or tammar wallaby. This antibody is known to react with a variety of eutherian species including the horse (Kelley & Mahaffey, 1998), cat (Day et al. 1999), mink (Chen et al. 1997; Chen & Aasted, 1998), ferret (Coleman et al. 1998) and dog (Christgau et al. 1998). In contrast, Jones et al. (1993) and Coutinho et al. (1995) found that polyclonal anti-CD79a stained the cells of the Brazilian white bellied opossum. This suggests that polyclonal anti-CD79a would be of value in future studies of metatherian tissues as polyclonal antibodies can react with several epitopes throughout the target molecule (Zola, 1995).

Anti-CD79b

In contrast to anti-CD79a, anti-CD79b heavily stained cells within the mantle zones of the follicles and a few scattered cells within the medullary areas of the lymph nodes and in the mantle of follicles in the white pulp areas of the tammar wallaby spleen. It also reacted with lymphoid cells in the other tissues tested. These results were similar to earlier reports for this species and others (Hemsley et al. 1995).

Anti-CD3 and CD5

The monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to CD3 and CD5 stained a similar range of cells in the tammar wallaby. Polyclonal anti-CD3 has been widely used amongst a variety of eutherian species (Keresztes et al. 1996). It has also been used successfully in a few studies of non-eutherians, including opossums (Jones et al. 1993; Coutinho et al. 1995), koalas (Wilkinson et al. 1994), ringtail and brushtail possums and the tammar wallaby (Hemsley et al. 1995) as well as chickens (Jones et al. 1993) and ducks (Bertram et al. 1996). Mason et al. (1989) described the polyclonal version of this antibody as not comparable in terms of reactivity as the monoclonal was used at a high concentration. Hemsley et al. (1995) found the monoclonal antibody worked at high concentrations but preferred the polyclonal CD3 antibody. Similarly, this study found the monoclonal and polyclonal antibody to work equally as well as the other but found that a lower dilution of the monoclonal antibody was required compared to the polyclonal antibody.

Anti-J-chain

Antibodies to brushtail possum J-chain failed to react with juvenile tammar wallaby spleen sections. All antibody dilutions resulted in non-specific staining with the exception of 1 : 10 000 that showed no staining. As a result, the antibody was not tested on any other samples. Takahasi et al. (1996) found J-chain was expressed in invertebrates and vertebrate species including mammals, fish and amphibians, suggesting J chain was a highly preserved molecule that arose prior to the evolution of Ig molecules. In eutherians, the main role of J-chain is to assemble the Ig polymers and it is involved in the differentiation of B-cells into IgM-secreting cells. J-chain also has a role in secretion of IgM and the binding of polymeric IgM and IgA to transport receptors on the surface of epithelial cells (Koshland, 1985). One J-chain molecule is incorporated into one polymer molecule (Koshland, 1985). J-chain is therefore a secreted product (when present in the Ig complex), and it may be spread throughout the tissue, resulting in background staining. However, endogenous J-chain spread throughout the tissue does seem unlikely as it would be removed during the deparaffinization and preparative steps prior to antibody addition. Fresh adult brushtail possum samples were not available but would help greatly in the diagnosis of the non-specific staining as previous work using this antibody has been shown to recognize the J-chain in brushtail possum milk (Adamski & Demmer, 2000). If the antibody failed to recognize lymphoid cells in adult brushtail possum paraffin sections it may suggest that the antibody is only able to react with the native protein and cannot react with the paraffin-embedded tissue. Alternatively, another antigen retrieval method may be required.

The tammar wallaby polymeric Ig receptor has recently been cloned by our laboratory (Taylor et al. 2002). Sequencing of the J-chain in the tammar wallaby will allow a comparison between the brushtail possum and tammar wallaby J-chain and may clarify the degree of similarity or difference and, hence, may explain the lack of reactivity with the tammar wallaby tissues.

Anti-T-cell receptor α

The newly designed and synthesized tammar wallaby specific anti-TCRα antibody worked well on the tammar wallaby tissues tested. Anti-TCRα strongly reacted with T-cells in the juvenile tammar wallaby spleen and adult thoracic thymus samples. This antibody in the future will allow the distribution of TCRα+ cells to be identified in a range of paraffin-embedded tissue sections and also has the potential to be used in flow cytometry studies to determine the numbers of cells in certain tissues and blood of marsupial species expressing the TCRα molecule.

In combination with other antibodies such as anti-CD3 and anti-CD5, anti-TCRα will identify cells that have the potential to be TCRγδ+. Very recently, the TCRδ cDNA sequence has become available for the tammar wallaby (Harrison, personal communication). The numbers of αβ and γδT-cells in different marsupials during development would be interesting to assess considering the differences amongst eutherian species. In large farm animals, the majority of T-cells are γδ unlike those in rodents and humans that are primarily αβ T-cells (Butler, 1998). γδTCR+ cells are usually the first to appear in ontogeny and are rare in adult lymphoid tissues (Takeuchi et al. 1992). An antibody to TCRδ could provide further information about the distribution of certain T-cell subsets within the marsupial immune system.

Tissue bed structure

The tammar wallaby has both a cervical and a thoracic thymus (Yadav, 1973). Both thymuses were investigated. Both the thoracic and the cervical thymus has a similar histological appearance to each other (Basden et al. 1997). Immunohistochemical studies revealed that both anti-CD3 and anti-CD5 stained similar numbers of T-cells throughout both the cervical and the thoracic thymuses, despite extensive involution. This suggests that, like other mammalian species, the thymus in the tammar wallaby can produce T-cells throughout life even when the majority of the tissue is replaced by adipose (Marusic et al. 1998).

The distribution of lymphocytes stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD5 suggests that lymphocytopoiesis occurs in the outer cortex, and blast cells differentiate into small lymphocytes in the inner cortex similar to the human thymus (von Gaudecker, 1978). Early lymphocytes observed in the outer cortex presumably do not express CD3 and CD5 as yet, whereas the more mature lymphocytes located in the inner cortex and medulla do express CD3 and CD5.

The spleen and lymph nodes were similar histologically in appearance to that described by Basden et al. (1996, 1997), and immunohistochemically similar to the description of Hemsley et al. (1995).

Histologically, the GALT of the tammar wallaby was similar to that described previously by Basden et al. (1997). Immunohistochemistry studies revealed that large numbers of T-cells were present amongst the villi. Anti-CD3 stained more cells than anti-CD5, and suggested that there were some CD3 expressing T-cells present in the gut that do not express CD5 and some that do. These may represent different T-cell subsets although this requires further investigation with more specific antibodies. It was interesting to note that there were virtually no B-cells stained using anti-CD79b in the tammar wallaby gut. In contrast in the eastern grey kangaroo GALT samples, B-cells are stained with anti-CD79b and were associated with follicles and germinal centres (Old & Deane, 2001). The tammar wallaby does not have follicular aggregations or Peyer's patches present (Basden et al. 1997). B-cells may be absent, or be too immature to express CD79b, or not express CD79b at all in the tammar wallaby gut. Alternatively, B-cells may only frequent the gut area after a large antigenic stimulation. This observation clearly requires more investigation with more specific antibodies to confirm the presence or absence of B-cells in the tammar wallaby gut.

No BALT was observed in the adult tammar wallaby lungs. The lungs were similar in appearance to those described previously by Runciman et al. (1996). Rare T- and B-cells were observed using anti-CD3, anti-CD5 and anti-CD79b amongst the alveoli.

It has been known for some time that anti-CD3, anti-CD5 and anti-CD79b recognize cognate molecules in marsupial lymphoid tissues (Jones et al. 1993). Of the range of antibodies assessed in this paper only tammar wallaby specific anti-TCRα reacted with cells in tammar wallaby tissues. There is still a clear need to develop more specific antibodies to recognize cells in the lymphoid tissues of marsupials, particularly those associated with development and activation as these areas are still largely unexplored.

References

- Adamski FM, Demmer J. Immunological protection of the vulnerable marsupial pouch young: two periods of immune transfer during lactation in the marsupial, Trichosurus vulpecula. Dev. Comparative Immunol. 2000;24:491–502. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JR, Ferguson MWJ. Ontological wound-healing studies in Monodelphis domestica from birth to adulthood. In: Saunders NR, Hinds L, editors. Marsupial Biology: Recent Research, New Perspectives. Sydney: UNSW Press; 1997. pp. 254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Baker ML, Gemmell E, Gemmell RT. Ontogeny of the brushtail possum, Trichosurus vulpecula. Anat. Record. 1999;256:354–365. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19991201)256:4<354::AID-AR3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft JD, Stevens AS. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Basden K, Cooper DW, Deane EM. Development of the blood-forming tissues of the tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 1996;8:989–994. doi: 10.1071/rd9960989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basden K, Cooper DW, Deane EM. Development of the lymphoid tissues of the tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 1997;9:243–254. doi: 10.1071/r96032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EM, Wilkinson RG, Lee RG, Jilbert AR, Kotlarski I. I. Identification of duck T lymphocytes using an anti-human T cell (CD3) antiserum. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996;51:352–363. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(95)05528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JE. Immunoglobulin diversity, B cell and antibody repertoire development in large farm animals. Rev. Sci. Techn Officers Int. Epiz. 1998;17:42–70. doi: 10.20506/rst.17.1.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WS, Aasted B. Analyses of leucocytes in blood and lymphoid tissues from mink infected with Aleutian mink disease parvovirus (AMDV) Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1998;63:317–334. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(98)00110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WS, Pedersen M, Gramnielsen S, Aasted B. Production and characterisation of monoclonal antibodies against mink leucocytes. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1997;60:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christgau M, Caffesse RG, Newland JR, Schmalz G, D’Souza RN. Characterisation of immunocompetent cells in the diseased canine peridontium. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1998;46:1443–1454. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisternas PA, Armati PJ. Immune system cell markers in the northern brown bandicoot, Isoodon macrourus. Dev. Comparative Immunol. 2000;24:771–782. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(00)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LA, Erdman SE, Schrenzel MD, Fox JG. Immunophenotypic characterisation of lymphomas from the mediastinum of young ferrets. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1998;59:1281–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho HB, Sewell HF, Tighe P, King G, Nogueira JC, Robalinho TI, et al. Immunocytochemical study of the ontogeny of the marsupial Didelphis albiventris immune system. J. Anat. 1995;187:37–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day MJ, Kyaw-Tanner M, Silkstone MA, Lucke VM, Robinson WF. T cell rich B cell lymphoma in the cat. J. Comparative Pathol. 1999;120:155–167. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1998.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Porrero JA, Manaia A, Jimeno J, Lasky LL, Dieterien-Lievre F, Godin IE. Antigenic profiles of endothelial and haematopoietic lineages in murine intraembryonic hemogenic sites. Dev. Comparative Immunol. 1998;22:303–319. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(98)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gaudecker B. Ultrastructure of the age-involuted human thymus. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;186:507–525. doi: 10.1007/BF00224939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed A, Hruban RH, Gage W, Pettis G, Fox WM. Immunohistochemical expression of CD68 antigen in human peripheral blood T cells. Human Pathol. 1994;25:872–876. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley SW, Canfield PJ, Husband AJ. Immunohistological staining of lymphoid tissue in four Australian marsupial species using species cross-reactive antibodies. Immunol. Cell Biol. 1995;73:321–325. doi: 10.1038/icb.1995.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Cordell J, Beyers A, Tse A, Mason D. Detection of T and B cells in many animal species using cross-reactive anti-peptide antibodies. J. Immunol. 1993;150:5429–5435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LC, Mahaffey EA. Equine malignant lymphomas: Morphologic and immunohistochemical classification. Vet. Pathol. 1998;35:241–252. doi: 10.1177/030098589803500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keresztes G, Glavits R, Krenacs L, Kurucz E, Ando I. An anti-CD3-epsilon serum detects T lymphocytes in paraffin-embedded pathological tissues in many animal species. Immunol. Lett. 1996;50:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland ME. The coming of age of the immunoglobulin J chain. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1985;3:425–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.03.040185.002233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusic M, Turkalij-Kljajic M, Petrovecki M, Uzarevic B, Rudolf M, Batinic D, et al. Indirect demonstration of the lifetime function of human thymus. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998;111:450–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason DY, Cordell JL, Brown M, Pallesen G, Ralfkiaer E, Rothbard J, et al. Detection of T-cells in parrafin wax embedded tissue using antibodies against a peptide sequence from CD3 antigen. J. Clin. Pathol. 1989;42:1194–1200. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.11.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason DY, Cordell JL, Gaulard P, Tse AGD, Brown MH. Immunohistological detection of human cytotoxic/suppressor T cells using antibodies to a CD8 peptide sequence. J. Clin. Pathol. 1992;45:1084–1088. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.12.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old JM, Deane EM. Histology and immunohistochemistry of the gut associated lymphoid tissue of the eastern grey Kangaroo. J. Anat. 2001;199:657–662. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19960657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old JM, Deane EM. The gut-associated lymphoid tissues of the northern brown bandicoot. Dev. Comparative Immunol. 2002 doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(02)00031-9. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parums DV, Cordell JL, Micklem K, Hervet AR, Gatter KC, Mason MY. JC70: a new monoclonal antibody that detects vascular endothelium associated antigen on routinely processed tissue sections. J. Clin. Pathol. 1990;43:752–757. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.9.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runciman SIC, Baudinette RV, Gannon BJ. Postnatal development of the lung parenchyma in a marsupial – the tammar wallaby. Anat. Record. 1996;244:193–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199602)244:2<193::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahasi T, Iwase T, Takenouchi N, Saito M, Kobayashi K, Moldoveanu Z, et al. The joining (J) chain is present in invertebrates that do not express immunoglobulins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 1996;93:1886–1891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi N, Ishiguro N, Shinagawa M. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of bovine T cell receptor γ and δ chain genes. Immunogenetics. 1992;35:89–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00189517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CL, Harrison GA, Watson CM, Deane EM. cDNA Cloning of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor of the Marsupial Macropus eugenii (Tammar wallaby) Eur. J. Immunogenetics. 2002;29:87–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2370.2002.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss LM, Arber DA, Chang KL. CD68 – a review. Appl. Immunohistochem. 1994;2:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R, Kotlarski I, Barton M. Further characterisation of the immune response of the koala. Vet Immunol. Immunopathol. 1994;40:325–339. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M. The presence of the cervical and thoracic thymus lobes in marsupials. Aust. J. Zool. 1973;21:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Taeya M, Ling X, Nagasaki A, Takahashi K. Interspecies reactivities of anti-human macrophage monoclonal antibodies to various animal species. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1996;44:845–853. doi: 10.1177/44.8.8756757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zola H. Introduction. In: Zola H, editor. Monoclonal Antibodies – the Second Generation. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers Limited; 1995. pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zuccolotto PD, Harrison GA, Deane EM. Cloning of marsupial T cell receptor alpha and beta constant region cDNAs. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:103–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]