While patellar luxation is acknowledged as a developmental disease, there is no consensus on the exact course of events in its pathogenesis. One thing is clear, patellar luxation is the result of anatomic abnormalities involving the entire hind limb. The most popular theory holds that the problem starts in the hip with coxa vara and decreased anteversion of the femoral head and neck (1). In other words, there is a decreased angle of inclination between the femoral longitudinal axis and the femoral neck, combined with a lesser caudal to cranial angle of the femoral neck. This skeletal abnormality in the growing animal displaces the extensor muscles of the hind limb, chiefly the quadriceps group, medially (1). This muscular displacement has an effect on the distal femoral physis, resulting in impaired growth of the medial side and accelerated growth of the lateral side of the distal extremity of the femur (1,2). The net effect is medial bowing and rotation of the distal extremity of the femur and proximal extremity of the tibia. The patella is simply pulled along with all the other bony and soft tissue structures. Further compounding the problem is the fact that a chronically luxated patella does not exert pressure in the trochlear groove, which is crucial in producing a groove of sufficient width and depth in the growing animal (1,2).

An alternate pathogenetic theory is based on the experimental observation that administration of estradiol results in the development of a shallow trochlear groove (1). This observation has caused some to wonder about the possibility of hormonal influences affecting the trochlear groove, thus resulting in patellar luxation. The previously described bony abnormalities may then follow as a result of chronic patellar luxation (1). Yet another theory suggests that decreased anteversion of the coxofemoral joint, which amounts to relative external rotation of the hip, might require compensatory internal rotation of the distal part of the limb to place the foot properly. This produces a lateral torsional force on the distal femoral physis, which places the trochlear groove lateral to the patella and initiates the bony changes previously outlined (3). Yet more research has suggested the possibility that the initial problem may be more muscle-related. Some young animals have been noted to have atrophic changes in the rectus femoris muscle that produce a “bowstring” effect in pulling the patella medially. Similarly, it has been observed that the origin of the cranial head of the sartorius muscle, which is found on the cranial wing of the ilium, is located much more medially in dogs with medially luxating patellas (3). This exerts a medial pull on the patella, facilitating chronic luxation and the associated bony changes. Whichever theory is correct, skeletal changes may become evident within the first few weeks of life and steadily worsen until skeletal maturity.

What can be done surgically about patellar luxation both to prevent the skeletal deformities and to improve limb function once they have developed? Surgical techniques can be divided into those that involve bony structures and those that involve only soft tissues. Most patients will receive some combination of bony and soft tissue techniques. In general terms, surgery is indicated only in those dogs that are experiencing significant clinical signs or in young dogs where soft tissue techniques might be utilized in an attempt to mitigate the negative effects of the condition on growing bone. In the asymptomatic adult dog, despite the risk of degenerative joint disease and rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament, there is no evidence that surgery is beneficial prophylactically (4,5).

Soft tissue procedures include medial desmotomy, lateral imbrication, antirotational sutures, and release of medial musculature. These procedures can be used in the immature patient to modify abnormal forces on growing bones and in mature patients to supplement bony procedures. By themselves, they are seldom sufficient to correct patellar luxation (1,2,6–8).

Medial desmotomy refers to a releasing incision in the soft tissues on the medial side of the joint, including the medial retinaculum and joint capsule. Desmotomy allows release of contracted tissues that prevent the patella from returning to the trochlear groove. The releasing incision, including the joint capsulotomy, are left open. Leakage of synovial fluid is not a problem (1).

Lateral imbrication goes hand in hand with desmotomy in most cases, as it involves the use of “gathering sutures” to tighten up soft tissues contralateral to the luxation. This can be accomplished by closing a lateral arthrotomy with the lateral retinaculum in a “vest-over-pants” fashion, or it can be accomplished by using gathering sutures (mattress pattern) in the lateral periarticular soft tissues in the absence of an arthrotomy (1,2,6–8).

Antirotational sutures are similar to the extracapsular sutures used for repair of the cranial cruciate ligament. They can be passed behind the lateral fabella and then through the distal part of the straight patellar tendon. Alternatively, the suture can be passed in figure-8 fashion around the patella after being anchored behind the lateral faballa (6).

Muscle release procedures can be accomplished in a variety of ways. The rectus femoris muscle can be dissected away from the joint capsule and the adjacent femur and musculature as an extension of the medial desmotomy. Freeing the rectus femoris muscle, at least to the level of the middle of the femur, may relieve significant medially-directed tension on the patella. Alternatively, the origins of the rectus femoris muscle, on the caudal part of the ilium, or the cranial portion of the sartorius muscle, on the cranial wing of the ilium, may be transplanted to more lateral locations to help in reducing medial pull on the patella (3). Anecdotally, elevation of the origin of the rectus femoris muscle without transplantation has been advocated as a simple means of reducing medially-directed forces on the patella, especially in puppies.

The techniques that modify the bony structures in and around the stifle joint are the bread and butter of surgical correction for patellar luxation. These can be divided into those that augment the trochlear groove and those that transplant the tibial tuberosity (1,2,6–8).

Deepening of the trochlear groove was traditionally accomplished by the trochleoplasty technique. This involved the removal of articular cartilage and subchondral bone in the trochlear groove with a rongeur or bone rasp until sufficient depth had been achieved. While many good results have been reported with this technique, the morbidity is high and recovery can be protracted due to the slow deposition of thin fibrocartilage at the surgical site. For this reason and because of the existence of simple, effective techniques that preserve the articular cartilage, the trochleoplasty must be considered an antiquated technique (1,2,6–8). Trochlear wedge recession and a more recent modification, the trochlear block recession technique, both allow elevation of the articular cartilage in the trochlear groove, deepening of the groove, and replacement of the cartilage (9,10). The trochlear wedge recession technique involves removing an elliptical wedge of cartilage and subchondral bone from the trochlear groove, deepening the groove, and then replacing the wedge in the newly deepened groove (1,2,6–8,9). The block recession technique is similar, except that it involves a rectangular block of articular cartilage and subchondral bone rather than the elliptical wedge (10). Both the wedge and the block are held in place by the pressure applied by the patella, and no additional fixation is required. The block recession technique would appear to have several advantages over the wedge technique, including an increased depth to the trochlear groove especially at its proximal extent, increased patellar articular contact with the proximal trochlear groove, a greater surface area of deepened trochlear groove, and greater resistance to patellar luxation with the joint in extension (10,11).

Tibial tuberosity transposition (TTT) involves osteotomy of the insertion of the patellar tendon along with a portion of the tibial tuberosity and transplantation of this bone fragment to realign the quadriceps-patella-patellar tendon mechanism in a straight line. In medial patellar luxation, this involves lateral transplantation of the osteotomized fragment. The fragment must be large enough to accept a lag screw or 2 pins, the size of which will vary with the size of the patient (1,2,6–8). In large dogs, it is critical to utilize a lag screw or to supplement the pins with a figure-8 tension band wire. If the osteotomized fragment is not securely fixed in a large, active dog, there is a high probability that the fixation will break down. Proper alignment of the quadriceps-patella-patellar tendon unit is facilitated by performing the surgery with the animal in dorsal recumbancy. This allows the surgeon to visualize the alignment of the entire hind limb (6). Tibial tuberosity transposition (TTT) is the most important procedure to perform in the majority of medial patellar luxation cases. Indeed, failure to perform this procedure is the most common cause of surgical failure (7).

In the surgical cases from our own practice, TTT was performed in 71% of small breed cases and 86% of large breed cases. Wedge recession trochleoplasty was performed in 66% of small breed dogs and 29% of large dogs. Medial desmotomy was part of the surgical therapy in 73% of small dogs and 86% of large dogs, while lateral imbrication was utilized in 49% of small dogs and 57% of large dogs. In rare cases, major corrective osteotomy of the distal femur or proximal tibia may be required to restore a more normal limb alignment. These procedures are only indicated in the most severe cases and carry with them a guarded prognosis (6–8).The prognosis after surgical correction of patellar luxation is generally good, at least for those that are Grades 1, 2 or 3. In excess of 90% of cases achieve an acceptable functional outcome (6). Grade 4 luxations carry a more guarded prognosis, as do chronic luxations in middle-aged to older dogs; however, even these cases can usually be improved surgically. The most common postsurgical complication is reluxation, which occurs in approximately half of all surgical cases, although the reluxation is usually of a lower grade and frequently does not produce clinical signs (1,5–7). Other common postoperative complications include seroma formation, infection, and periodic lameness. This lameness is usually due to the presence of degenerative joint disease, which appears to progress equally in those joints that are treated surgically and those that are not (4,5,7). The author has also encountered a few cases where occasional mild lameness seems to be related to irritation over the pins used to stabilize the TTT. These dogs react with discomfort when the pin ends are palpated, despite the absence of swelling or radiographic changes. Pin removal has been curative.

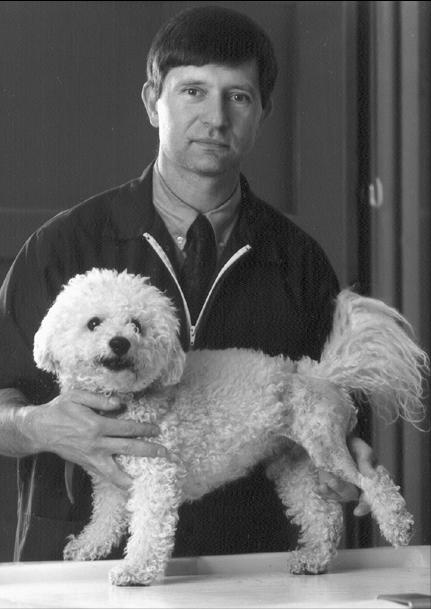

Figure 1.

Grade II medially luxating patella in the right hind limb of a 10-month-old golden retriever.

References

- 1.Roush JK. Canine patellar luxation. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1993;23:855–868. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(93)50087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulse DA. The stifle joint. In: Olmstead ML ed. Small Animal Orthopedics St Louis: Mosby, 1995:395–404.

- 3.L’Eplattenier H, Montavon P. Patellar luxation in dogs and cats: Pathogenesis and diagnosis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2002;24:234–239. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wander KW, Powers BE, Schwarz PD. Cartilage changes in dogs with surgically treated medial patellar luxations. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 1999;12:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willauer CC, Vasseur PB. Clinical results of surgical correction of medial luxation of the patella in dogs. Vet Surg. 1987;16:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1987.tb00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piermattei DL, Flo GL. Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997:516–534.

- 7.L’Eplattenier H, Montavon P. Patellar luxation in dogs and cats: Management and prevention. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2002;24:292–298. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denny HR, Butterworth SJ. A Guide to Canine and Feline Orthopedic Surgery. Oxford: Blackwell Sci 2000:517–525.

- 9.Slocum B, Devine T. Trochlear recession for correction of luxating patella in the dog. J Amer Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talcott KW, Goring RL, de Haan JJ. Rectangular recession trochleoplasty for treatment of patellar luxation in dogs and cats. Vet Comp Orthop Traumat. 2000;13:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson AL, Probst CW, Decamp CE, et al. Comparison of trochlear block recession and trochlear wedge recession for canine patellar luxation using a cadaver model. Vet Surg. 2001;30:140–150. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2001.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]