Abstract

We investigated responses to neurotensin in human promyelocytic leukaemia HL-60 cells.

Neurotensin increased the cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in a concentration-dependent manner and also produced inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3).

Among the tested neurotensin analogues, neurotensin 8-13, neuromedin-N, and xenopsin also increased [Ca2+]i, whereas neurotensin 1–11 and neurotensin 1–8 did not elicit detectable responses.

SR48692, an antagonist of NTR1 neurotensin receptors, blocked the neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i increase, whereas levocabastine, which is known as an NTR2 neurotensin receptor antagonist, did not attenuate the neurotensin-evoked effect.

The expression of NTR1 neurotensin receptors was confirmed by Northern blot analysis and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR).

During 1.25% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-triggered granulocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells, the neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i rise became gradually smaller and completely disappeared 4 days after treatment with DMSO. The mRNA level for neurotensin receptors was also decreased after differentiation.

The results show that HL-60 cells express NTR1 neurotensin receptors and suggest that granulocytic differentiation involves transcriptional regulation of the receptors resulting in down-regulation of the neurotensin-induced signalling.

Keywords: Neurotensin, cytosolic Ca2+, phospholipase C, human hemopoietic cells, differentiation

Introduction

Neurotensin, the tridecapeptide ELYENKPRRPYIL, has been studied as a modulator in neuronal and non-neuronal systems (Kitabgi et al., 1985; Vincent, 1995). Neurotensin reveals its modulatory effect in almost every region of the nervous system including the cerebral cortex, terminals of striatal nucleus, hypothalamus, midbrain, cerebellar purkinje cells, retina, and spinal cord (Shi & Bunney, 1992a). In the central nervous system neurotensin is known to modulate the signals of dopaminergic neurons by regulating D2 receptors. Therefore, neurotensin displays activities similar to antipsychotics in clinical trials involving schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease (Nemeroff et al., 1992). It has been also reported that neurotensin potentiates the barbiturate- and ethanol-induced sedation and that it induces antinociception, catalepsy, and hypothermia.

For non-neuronal systems, major roles of neurotensin have been demonstrated in the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular system. Neurotensin is localized at the intestinal mucosa (endocrine N-cells) where it is thought to be involved in intestinal contraction (Buhner & Ehrlein, 1989). Intravenous injection of neurotensin changes the concentration of insulin, glucagon, and pituitary hormones including thyroid releasing hormone (Kitabgi et al., 1985; Schimpff et al., 1995). It also induces vasodilatation and affects vascular permeability by way of vascular, portal vein, and smooth muscle contraction (Bachelard et al., 1992). The neurotensin effect on the cardiovascular system somewhat depends on the species, because neurotensin causes hypotension in dogs but hypertension in guinea pigs. It has been reported that endothelial cells of the umbilical vein also express the neurotensin receptor which is involved in the increase of intracellular Ca2+ (Schaeffer et al., 1995) and the production of prostacyclin (Schaeffer et al., 1997). However, it is not yet known what role neurotensin plays in hemopoietic or immune cells.

Neurotensin evokes two major actions at the cellular level. It causes inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) production and increase in the cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) through the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) (Goedert et al., 1984; Bozou et al., 1989; Hermans et al., 1992). In another signalling pathway, neurotensin modulates the intracellular cyclic nucleotide level including cyclic GMP (Gilbert & Richelson, 1984; Amar et al., 1985) and cyclic AMP (Bozou et al., 1986; Yamada et al., 1994).

HL-60 cells have served as a good model in which to study signal transduction of various pharmacological receptors before and after differentiation of the hemopoietic cells (Klinker et al., 1996). HL-60 cells can be forced to terminally differentiate into neutrophil-like cells by dibutyryl cyclic AMP, DMSO, or retinoic acid treatment and into adherent macrophage-like cells by 1, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 and phorbol esters (Klinker et al., 1996; Collins et al., 1978).

Here we report the expression of PLC-coupled neurotensin receptors in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukaemia cells and the down-regulation of neurotensin-induced signalling during granulocytic differentiation into neutrophil-like cells.

Methods

Cell culture

HL-60, U937, K562, Jurkat T, H9, and U266 cells were maintained at 37°C in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated bovine calf serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed daily. We induced differentiation of HL-60 cells by incubating them in 1.25% DMSO for 6 days. We observed the morphology of the cells and monitored fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i increase, which was only detectable in differentiated HL-60, as indication of differentiation into neutrophil-like cells. We also counted viable cells by the Trypan-blue exclusion method.

Isolation of human neutrophils

Human neutrophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors as previously described (Pember et al., 1983). Isolated cells were suspended in phosphate buffered saline/glucose (in mM: KCl 2.6, KH2PO4 1.5, MgCl2 0.5, NaCl 136, Na2PO4 8 and glucose 5.5, pH 7.4) and used immediately.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

The level of intracellular Ca2+ was determined using fura-2 tetraacetoxymethyl ester (fura-2/AM) as we have previously described (Choi & Kim, 1997). Briefly, the cell suspension was incubated in fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 medium with 3 μM fura-2/AM at 37°C for 60 min with continuous stirring. Sulphinpyrazone (250 μM) was added to prevent dye leakage. Changes in the fluorescence ratio were measured at dual excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm and emission wavelength of 500 nm. The calibration of the fluorescence signal in terms of [Ca2+]i was performed according to Grynkiewicz et al. (1985).

Measurement of InsP3 production

InsP3 production was determined by competition assay with [3H]-InsP3 as described previously (Lee et al., 1997). To determine InsP3 production, 1×106 cells were stimulated with drugs. The reaction was terminated by addition of ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid containing 10 mM EGTA. The supernatant of the cell lysate was saved and the trichloroacetic acid was removed by extraction with diethyl ether. The aqueous fraction was neutralized with 200 mM Trizma base and adjusted to pH 7.4. 20 μl of extract was added to 20 μl of assay buffer (100 μM Tris buffer containing 4 mM EDTA) and 20 μl [3H]-InsP3 (0.1 μCi ml−1). The mixture was incubated for 15 min on ice and then centrifuged at 2,000×g for 10 min. One hundred μl water and 1 ml liquid scintillation cocktail were added to the pellet to measure the radioactivity. The InsP3 concentration in the sample was determined by comparison to a standard curve and expressed as pmol mg−1 of protein. The total cellular protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976) after sonication of 1×106 cells.

Measurement of cyclic AMP

Intracellular cyclic AMP was determined by measuring the formation of [3H]-cyclic AMP from [3H]-adenine nucleotide pools as previously described (Choi & Kim, 1997). Briefly, cells were loaded with [3H]-adenine (1 μCi ml−1) in complete medium for 24 h. After the loading, the cells were washed two times with Locke's solution (in mM: NaCl 154, Kcl 5.6, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2.2, HEPES 5, and glucose 10, pH 7.3). 1×106 cells were aliquoted into Eppendorf tubes for stimulation. The stimulation reaction was stopped by addition of 1 ml ice-cold 5% (v/v) trichloroacetic acid containing 1 μM unlabelled cyclic AMP. [3H]-cyclic AMP and [3H]-ATP were separated using sequential chromatography on Dowex AG50W-X4 (200–400 mesh) cation exchanger and a neutral alumina column. The increase in intracellular cyclic AMP concentration was presented as [3H]-cyclic AMP/([3H]-ATP+[3H]-cyclic AMP)×103.

RNA isolation and RT–PCR

Total cellular RNA was prepared from undifferentiated and DMSO-induced differentiated HL-60 cells by the method of Chomczynski & Sacchi (1987). Poly(A)+-RNA was isolated from total RNA by oligo(dT)-cellulose column chromatography (Boehringer Mannheim). One μg of poly(A)+ mRNA was used as template for the first-strand cDNA synthesis using SUPERSCRIPT II reverse transcriptase (GIBCO-BRL) in a final volume of 40 μl supplemented with 50 ng of random hexamer and 500 ng of oligo(dT)12-18. Three μl of the reverse transcriptase reaction mixture was amplified with 20 pmol of subtype specific oligonucleotide primers (human NTR1: 1090-1732, 25mer; 5-aaCACCTTCATGTCCTTCATATTCC; 3-gcggatccTCTGCCTGACCCCCATC; Vita et al., 1993) using Pfu polymerase. The cycle profile was as follows: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C and 1 min at 72°C for 35 cycles, and finally, a 10-min extension at 72°C. The PCR products and 1 Kb ladder (GIBCO-BRL) were electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromide. The DNA fragments were inserted into the HincII site of the pBluescript II SK(+) vector and sequenced to confirm the authenticity of the neurotensin receptor gene.

Northern blot analysis

Poly (A)+-RNA (10 μg per lane) was resolved by electrophoresis through 1% agarose gel containing 660 mM formaldehyde and transferred to a nylon membrane (ICN, East Hills, NY). The blot was hybridized with each human neurotensin receptor cDNA probe (listed above) labelled by random primer extension with [α-32P]dCTP and Klenow enzyme. The hybridization was performed at 65°C in a solution containing 10% polyethylene glycol, 7% SDS, EDTA 10 mM, NaCl 250 mM, Na2HPO4 85 mM (pH 7.2), denatured salmon sperm DNA (100 μg ml−1) and the radiolabelled probes (5×105 c.p.m. ml−1). After hybridization, the blot was washed twice in 1×saline-sodium citrate (SSC; 300 mM NaCl and 30 mM sodium citrate) solution containing 0.1% SDS at room temperature, three times in 0.2×SSC with 0.1% SDS at 65°C, twice in 0.1×SSC at room temperature. The membrane was later reprobed with the cDNA of the human ribosomal large subunit protein 32 (a gift from Dr H.S. Shin) as a control.

Materials

RPMI 1640 and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.). Bovine calf serum was obtained from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, UT, U.S.A.). Neurotensin, neurotensin fragments 1–8, 1–11 and 8–13, neuromedin N, xenopsin, cyclic AMP, EGTA, trichloroacetic acid, isobutyl methyl xanthine (IBMX), fMLP, DMSO, and sulphinpyrazone were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Ionomycin and PMA were obtained from Research Biochemicals Inc. (Natick, MA, U.S.A.). [3H]-adenine and [3H]-InsP3 were purchased from NEN (Boston, MA, U.S.A.). Fura-2/AM was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). Levocabastine (Schotte et al., 1986) was a gift from Dr Marcel Janssen (Janssen Research Foundation) and SR48692 (Gully et al., 1993) was a gift from Dr Danielle Gully (Sanofi Recherche).

Analysis of data

All quantitative data are expressed as the means±s.e.mean. The results were analysed for differences using unpaired Student's t-test. We calculated half maximal effective concentration (EC50) and half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) with the AllFit program (De Lean et al., 1978).

Results

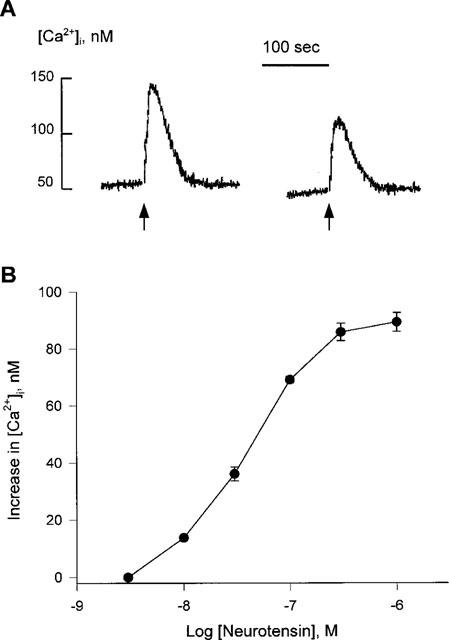

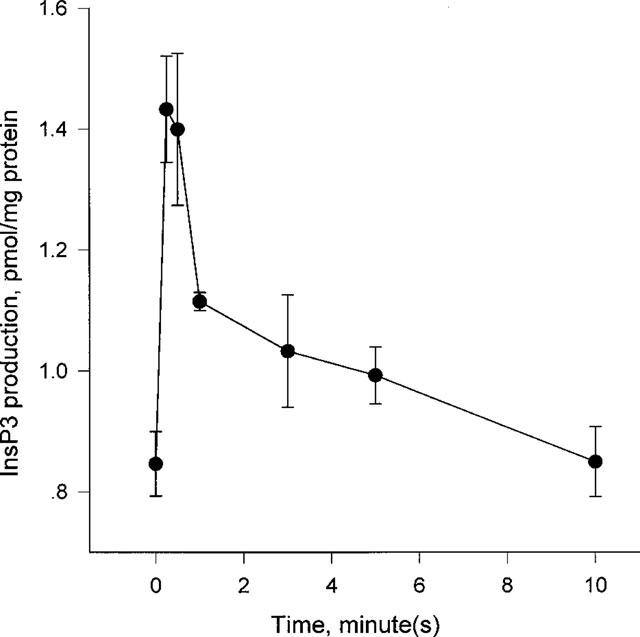

We examined the neurotensin-induced responses in HL-60 cells. Neurotensin (300 nM) triggered the [Ca2+]i rise in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+ in fura-2-loaded undifferentiated cells (Figure 1A). Neurotensin elevated the [Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner at maximal and half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) of 300 and 38.5±3.0 nM, respectively (Figure 1B). We tested the production of InsP3 upon neurotensin treatment, because neurotensin elicited [Ca2+]i rise in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Figure 2 shows that treatment with 300 nM neurotensin evoked production of InsP3 with the maximum effect seen 15 s after treatment.

Figure 1.

Neurotensin-induced increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in undifferentiated HL-60 cells. (A) Fura-2/AM-loaded HL-60 cells were challenged with 300 nM neurotensin with (left) or without (right) 2.2 mM extracellular Ca2+. The level of cytosolic Ca2+ was measured as described in Methods. A typical trace from more than 20 separate experiments is shown. (B) Fura-2/AM-loaded HL-60 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of neurotensin. The peak height of each stimulation was monitored. Each result is the means±s.e.mean from triplicate assays. The result is representative of five separate experiments. The results were reproducible.

Figure 2.

Neurotensin-induced InsP3 generation in undifferentiated HL-60 cells. Cells were stimulated with 300 nM neurotensin for the indicated times. The levels of InsP3 produced were measured as described in Methods. Each point is the means±s.e.mean of triplicate measurements. The result is representative of six separate experiments and were reproducible.

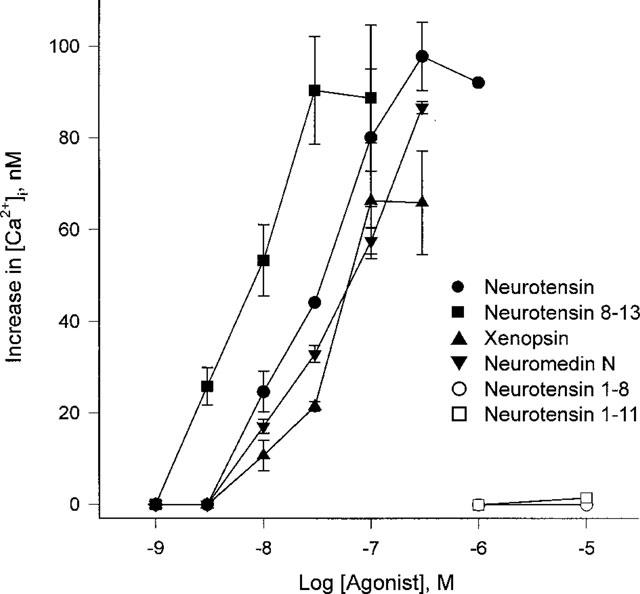

To compare the potency of neurotensin analogues in elevating [Ca2+]i, we used several neurotensin peptide fragments and related peptide hormones. As shown in Figure 3, neurotensin fragment 8-13, neuromedin N, and xenopsin increased the [Ca2+]i with an EC50 of 9.9±3.2 nM, 40.2±8.3 nM and 37.5±4.8 nM, respectively. However, neurotensin fragments 1–8 and 1–11 did not elicit an increase in [Ca2+]i at concentrations up to 10 μM. We further tested whether the neurotensin response overlapped the responses elicited by other peptide hormones. Among the tested peptide hormones bradykinin, substance P, angiotensin II, somatostatin, galanin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), cholecystokinin, and endothelin did not change the [Ca2+]i, but thrombin did increase the [Ca2+]i in HL-60 cells (Table 1). However, thrombin pretreatment did not block a subsequent response to neurotensin. In addition, 300 μM extracellular ATP, 300 μM histamine, 3 μM platelet-activating factor, and 100 nM small peptide WKYMVm (Seo et al., 1997), which are all known to elicit [Ca2+]i rise in HL-60 cells, also did not overlap with neurotensin in its [Ca2+]i elevating effect (data not shown). The results suggest that neurotensin has its own receptor on HL-60 cells and elevates [Ca2+]i through activation of PLC.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependent increases in cytosolic Ca2+ by neurotensin and its analogues. Undifferentiated HL-60 cells were treated with various concentrations of neurotensin, neurotensin 8–13 fragments, 1–11 fragments, 1–8 fragments, neuromedin N, and xenopsin. The peak height of each stimulation was monitored. Each result is the means±s.e.mean from triplicate assays. The result is representative of four separate experiments. The results were reproducible.

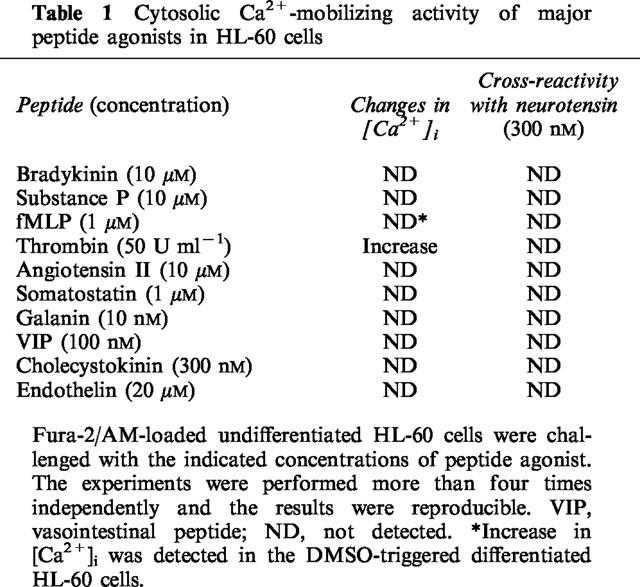

Table 1.

Cytosolic Ca2+-mobilizing activity of major peptide agonists in HL-60 cells

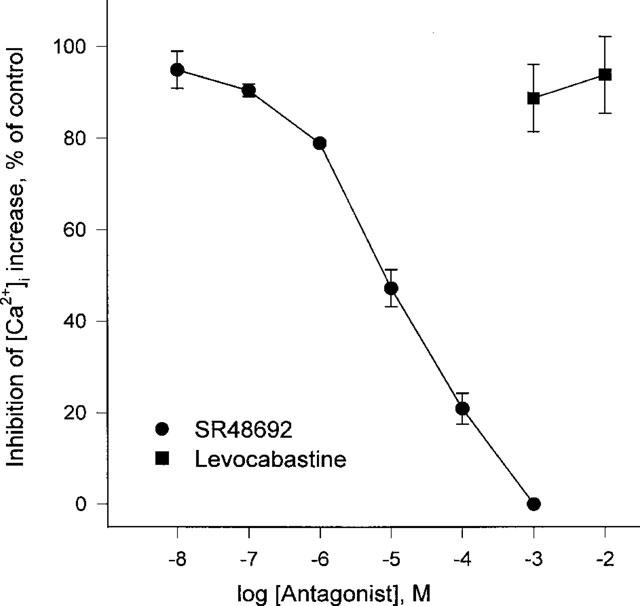

To identify the neurotensin receptor subtype expressed on HL-60 cells, subtype-specific antagonists were tested. It is generally accepted that SR48692 (Gully et al., 1993) and levocabastine (Schotte et al., 1986) block the neurotensin receptors NTR1 and NTR2, respectively. SR48692 inhibited the neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i increase in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 of 14.0±0.2 nM (Figure 4). However, levocabastine did not inhibit the neurotensin-induced effect even at millimolar concentrations. The results suggest that HL-60 cells express NTR1 neurotensin receptors.

Figure 4.

The effects of SR48692 and levocabastine on neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i rise in HL-60 cells. SR48692 or levocabastine were added to fura-2-loaded cells at the indicated concentrations. After 3 min the cells were challenged with 300 nM neurotensin. The peak heights of neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i rise were monitored. The experiments were performed three times independently, and the results were reproducible. Each result is the means±s.e.mean from triplicate assays.

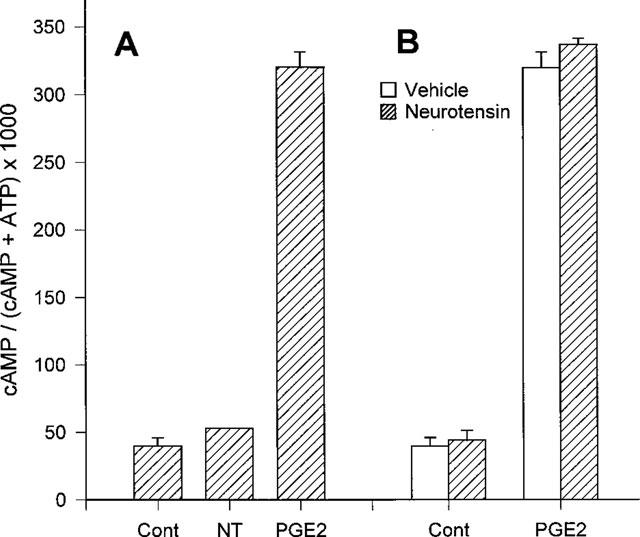

It has been reported that neurotensin receptors are also coupled to adenylyl cyclase (Yamada et al., 1994). So we tested whether neurotensin regulates cyclic AMP signalling in HL-60 cells. 300 nM neurotensin did not have any effect on cyclic AMP production, whereas prostaglandin E2 did increase the cyclic AMP level (Figure 5A). In addition, simultaneous treatment or pretreatment with neurotensin did not affect the prostaglandin E2-induced cyclic AMP formation (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Lack of neurotensin-induced changes in cyclic AMP level in HL-60 cells. (A) [3H]-adenine-loaded cells were preincubated with 1 mM IBMX for 15 min, then stimulated for 15 min with 300 nM neurotensin (NT) or 10 μM prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the presence of 1 mM IBMX. (B) Cells were preincubated with or without 300 nM neurotensin, then challenged with 10 μM prostaglandin E2 in the presence of 1 mM IBMX. The levels of cyclic AMP produced were measured as described in Methods. We expressed the cyclic AMP level as cyclic AMP/(cyclic AMP+ATP)×1000. Each point is the means±s.e.mean of triplicate measurements. The result is representative of six separate experiments. The results were reproducible.

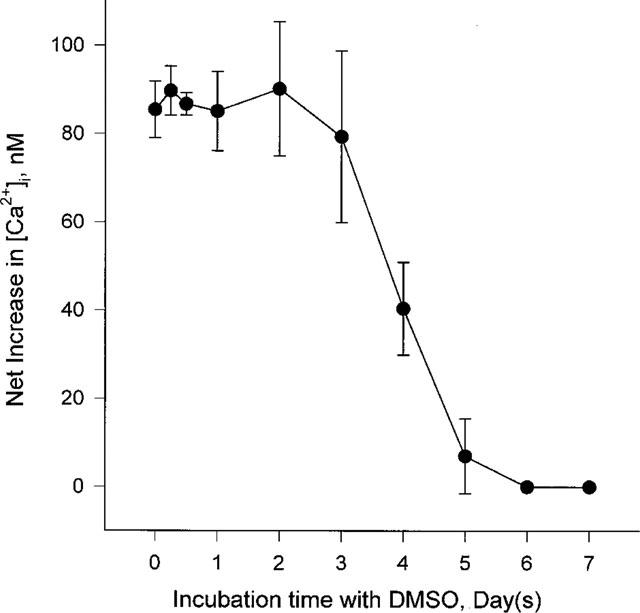

We further analysed changes in the neurotensin-induced effect during DMSO-induced differentiation. HL-60 cells had morphologically and physiologically differentiated into neutrophil-like cells after incubation with 1.25% DMSO for 6 days (so called granulocytic differentiation; Collins et al., 1978). In the neutrophil-like HL-60 cells a neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i increase was not detected. During the time course of the DMSO incubation the extent of the neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i increase became gradually smaller and disappeared completely after 4 days of incubation with DMSO (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Changes in neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i increase in HL-60 cells during DMSO-induced differentiation. Undifferentiated HL-60 cells were cultured with 1.25% DMSO containing medium for the indicated times, then 300 nM neurotensin-induced [Ca2+]i rise was examined. The peak height of the [Ca2+]i increase was recorded. The experiments were performed three times independently, and the results were reproducible. Each result is the means±s.e.mean of triplicate assays.

To confirm the expression and down-regulation of the neurotensin receptor in differentiated cells, PCR with specific probes (Vita et al., 1993) after a reverse transcriptase reaction with purified mRNA of HL-60 cells and Northern blot analysis were carried out. A specific DNA band was obtained, and the DNA fragment was confirmed by the digestion patterns obtained after reactions with HinfI (358 and 284 bp) and XhoI (467 and 175 bp) and by direct sequencing. The results clearly indicate that HL-60 cells express NTR1 neurotensin receptors (Figure 7A). The Northern blot analysis showed that the amount of neurotensin receptor mRNA in 6-day differentiated cells dramatically decreased in comparison to untreated control cells (Figure 7B). The result suggests that the signalling of neurotensin is down-regulated via the reduction of receptor expression during granulocytic differentiation.

Figure 7.

RT–PCR and Northern blot analysis of the expression of neurotensin receptors in undifferentiated and DMSO-induced differentiated HL-60 cells. (A) RNA extracted from undifferentiated HL-60 cells were reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Then amplification was performed using NTR1 neurotensin receptor specific primers and Pfu polymerase as described in Methods. Lane 1, 1 kb ladder; lane 2, PCR product (642 bp); lane 3, PCR product digested with HinfI (358 and 284 bp); lane 4, PCR product digested with XhoI (467 and 175 bp). (B) Poly(A)+-RNA (10 μg per lane) from control (lane C) and DMSO-induced differentiated HL-60 cells (lane D) was electrophoresed, transferred to a membrane, and hybridized with the human NTR1 neurotensin receptor cDNA (NTR1) for Northern blot analysis. The position of the 28S ribosomal RNA is indicated by an arrowhead. The human ribosomal large subunit protein 32 (RPL32) was used as a marker for RNA level.

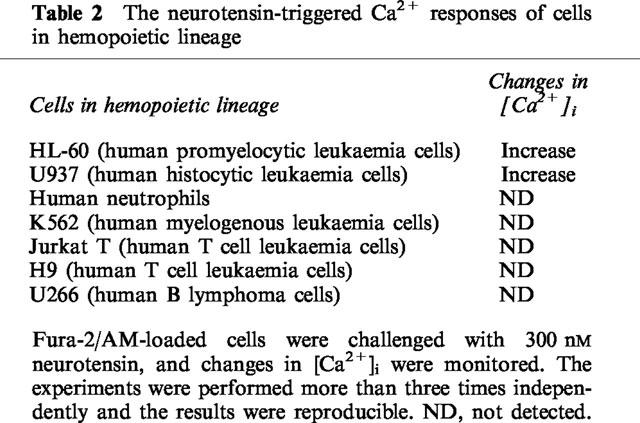

Furthermore, we tested the neurotensin signalling in hemopoietic cell lineages of various types of human lymphocytes or cell lines. As shown in Table 2, we could detect a neurotensin-evoked [Ca2+]i rise in human histocytic leukaemia U937 cells which are closely related to HL-60 cells in their differentiation phylogeny. However, there was no detectable Ca2+ mobilization in isolated human neutrophils which are the final form of granulocytic differentiation. In addition, human myelogenous leukaemia K562 cells, human T cell leukaemia Jurkat T cells and H9 cells, and human B lymphoma U266 cells, which are all of a distinct differentiation lineage, did not exhibit response to neurotensin treatment.

Table 2.

The neurotensin-triggered Ca2+ responses of cells in hemopoietic lineage

Discussion

Neurotensin is one of the important peptide hormones for both neuronal and non-neuronal systems that remain to be studied with regard to its mechanism of action. Here we demonstrate that human myeloid leukaemia cells, HL-60, express NTR1 neurotensin receptors. This is the first evidence that the NTR1 neurotensin receptor is expressed in hemopoietic cells.

At the present time, neurotensin receptors are believed to exist in three types: a high affinity brain-type neurotensin receptor (NTRH or NTR1), a low affinity brain-type receptor (NTRL or NTR2), and a low affinity mastocyte or macrophage neurotensin binding site. Since the NTR1 neurotensin receptor had been purified from rat brain (Mazella et al., 1985), it was cloned from rat brain tissue (Tanaka et al., 1990) and human colon adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells (Vita et al., 1993). Mazella et al. (1988) purified two distinct neurotensin-binding sites from an adult mouse brain homogenate, each of which differed in binding affinity and sensitivity to levocabastine. Based on the above results, NTR2 was then cloned from mouse brain (Mazella et al., 1996) and rat brain (Chalon et al., 1996). In addition, a third type of receptor was also identified as a low affinity binding site on mastocytes/macrophages; not only neurotensin but also bradykinin or substance P could bind to this receptor (Lazarus et al., 1977; Goldman & Bar-Shavit, 1983). It remains unclear whether this low affinity binding site's function is solely directed at neurotensin exactly because of its very low binding affinity for neurotensin and its cross-reactivity with bradykinin and substance P.

Schaeffer et al. (1995) have suggested major characteristics for the NTR1 neurotensin receptors: (i) a more potent effect by neurotensin fragments 8–13 than by neurotensin, (ii) lack of inhibition by levocabastine, (iii) lack of cross-binding other peptide hormones such as bradykinin and substance P and (iv) mRNA detection with specific NTR1 neurotensin receptor probes. Our results meet the above criteria for the expression of NTR1 neurotensin receptors in HL-60 cells. Neurotensin produced InsP3 and increased [Ca2+]i at nanomolar concentrations in HL-60 cells (Figure 1). Neurotensin fragments 8–13 was more potent in elevating [Ca2+]i than neurotensin (Figure 2). Levocabastine did not inhibit the neurotensin-evoked response, but NTR1 receptor antagonist SR48692 completely blocked it (Figure 3). The receptor did not cross-react with bradykinin and substance P (Table 1). Finally, the expression of the NTR1 receptor was detected by PCR and confirmed by sequencing (Figure 5).

Though the neurotensin receptor in HL-60 cells is clearly distinguishable from the mastocyte/macrophage neurotensin binding sites, it is of value to exclude the possibility that neurotensin may act on other receptors. HL-60 cells have several receptors which are coupled to Ca2+ mobilization such as receptors for extracellular ATP, histamine, platelet-activating factor, and WKYMVm. However, neurotensin independently elicited [Ca2+]i rise when cells were sequentially treated with the above stimulants (data not shown).

It has been suggested that neurotensin performs its role not only by elevating [Ca2+]i but also by regulating cyclic AMP levels. The neurotensin-induced increase in cyclic AMP and the subsequent activation of protein kinase A inhibit the dopaminergic signalling in the midbrain (Shi & Bunney, 1992b). In CHO-K1 cells expressing rat NTR1 neurotensin receptors, neurotensin increased the intracellular cyclic AMP level (Yamada et al., 1994). In N1E115 cells, neurotensin decreased the basal and the G-protein-mediated elevated cyclic AMP level (Bozou et al., 1986). However, neurotensin-induced changes in the cyclic AMP level were not detected in HL-60 cells (Figure 4). The result suggests that neurotensin may use different signalling pathways in different cells and tissues.

In addition, HL-60 cells are of hemopoietic lineage and can be triggered to differentiate into neutrophils or macrophages. It has been reported that the neurotensin receptors were undetectable in undifferentiated primary cultured neurons but did increase during differentiation (Chabry et al., 1990). Because the level of expression of the receptor is closely linked to the size of the physiological effect, it was valuable for us to test the expression of the neurotensin receptor in HL-60 cells during differentiation to neutrophils. We show here clearly that the signalling of neurotensin decreases during the DMSO-induced granulocytic differentiation. The down-regulation of the Ca2+ signalling correlated with a gradual decrease in the expression of neurotensin receptor mRNA. In contrast, the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation increased during the differentiation process (data not shown). Whenever there is a bacterial infection, the fMLP receptor is activated evoking superoxide production in granulocytes and macrophages. It has been generally accepted that PLC-coupled receptors are involved in defence mechanisms of the immune system such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and secretion of cytokines. However, it is still unclear what the physiological function of the down-regulation of the neurotensin receptor during differentiation may be. Neurotensin presumably plays a critical role in the early stages of hemopoietic differentiation and loses its physiological effect after differentiation. Cytokines including IL-3, granulocyte/macrophage-CSF, and macrophage-CSF, and granulocyte-CSF, play important roles in the early stages of differentiation from bone marrow cells. It is generally assumed that Ca2+ signalling in bone marrow cells regulates the effect of the cytokines described above (Cook et al., 1989). Moore et al. (1989) reported that neurontensin regulates the macrophage colony stimulating factor-induced myelopoiesis. Thus, it is possible to propose the interesting hypothesis that neurotensin modulates other differentiation signals such as are sent by cytokines or growth factors during differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr J.K. Seo for providing human neutrophils and valuable discussions. We are grateful to Ms G. Hoschek for editing this manuscript. This study was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Institute Program (Project BSRI-98-4435) from the Ministry of Education. S.Y. Choi was supported by research fund for young scientists from Korea Research Foundation (1998).

References

- AMAR S., MAZELLA J., CHECLER F., KITABGI P., VINCENT J.P. Regulation of cyclic GMP levels by neurotensin in neuroblastoma clone N1E115. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985;129:117–125. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BACHELARD H., GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., BENNETT T. Mechanisms contributing to the regional haemodynamic effects of neurotensin in conscious, unrestrained Long Evans rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:191–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOZOU J.C., AMAR S., VINCENT J.P., KITABGI P. Neurotensin-mediated inhibition of cyclic AMP formation in neuroblastoma N1E115 cells: involvement of the inhibitory GTP-binding component of adenylate cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol. 1986;29:489–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOZOU J.C., ROCHET N., MAGNALDO I., VINCENT J.P., KITABGI P. Neurotensin stimulates inositol trisphosphate-mediated calcium mobilization but not protein kinase C activation in HT29 cells. Biochem. J. 1989;264:871–878. doi: 10.1042/bj2640871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADFORD M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUHNER S., EHRLEIN H.J. Effects of neurotensin on motor patterns of canine duodenum and proximal jejunum. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1989;67:1534–1539. doi: 10.1139/y89-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHABRY J., CHECLER F., VINCENT J.P., MAZELLA J. Colocalization of neurotensin receptors and of the neurotensin-degrading enzyme endopeptidase 24-16 in primary cultures of neurons. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:3916–3921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-03916.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHALON P., VITA N., KAGHAD M., GUILLEMOT M., BONNIN J., DELPECH B., LE FUR G., FERRARA P., CAPUT D. Molecular cloning of a levocabastine-sensitive neurotensin binding site. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI S.Y., KIM K.T. Extracellular ATP-mediated increase of cytosolic cAMP in HL-60 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997;53:429–432. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOMCZYNSKI P., SACCHI N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acidic guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS S.J., RUSCETTI F.W., GALLAGHER R.E., GALLO R.C. Terminal differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia cells induced by dimethyl sulfoxide and other polar compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1978;75:2458–2462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.5.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOK N., DEXTER T.M., LORD B.I., CRAGOE E.J., JR, WHETTON A.D. Identification of a common signal associated with cellular proliferation stimulated by four haemopoietic growth factors in a highly enriched population of granulocyte/macrophage colony-forming cells. EMBO J. 1989;8:2967–2974. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LEAN A., MUNSON P.J., RODBARD D. Simultaneous analysis of families of sigmoidal curves: application to bioassay, radioligand assay, and physiological dose-response curves. Am. J. Physiol. 1978;235:E97–E102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.2.E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILBERT J.A., RICHELSON E. Neurotensin stimulates formation of cyclic GMP in murine neuroblastoma clone N1E115. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1984;99:245–246. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOEDERT M., PINNOCK R.D., DOWNES C.P., MANTYH P.W., EMSON P.C. Neurotensin stimulates inositol phospholipases hydrolysis in rat brain slices. Brain Res. 1984;323:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDMAN R., BAR-SHAVIT Z. On the mechanism of the augmentation of the phagocytic capability of phagocytic cells by Tuftsin, substance P, neurotensin, and kentsin and the interrelationship between their receptors. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1983;419:143–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb37099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRYNKIEWICZ G., PEINIE M., TSIEN R.Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GULLY D., CANTON M., BOIGEGRAIN R., JEANJEAN F., MOLIMARD J.C., PONCELET M., GUEUDET C., HEAULME M., LEYRIS R., BROUARD A., PELAPRAT D., LABBE-JULLIE C., MAZELLA J., SOUBRIE P., MAFFRAND J.P., ROSTENE W., KITABGI P., LE FUR G. Biochemical and pharmacological profile of a potent and selective nonpeptide antagonist of the neurotensin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:65–69. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMANS E., MALOTEAUX J.M., OCTAVE J.N. Phospholipase C activation by neurotensin and neuromedin N in chinese hamster ovary cells expressing the rat neurotensin receptor. Mol. Brain Res. 1992;15:332–338. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90126-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITABGI P., CHECLER F., MAZELLA J., VINCENT J.P. Pharmacology and biochemistry of neurotensin receptors. Rev. Clin. Basic Pharmacol. 1985;5:397–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINKER J.F., WENZEL-SEIFERT K., SEIFERT R. G-protein-coupled receptors in HL-60 human leukemia cells. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996;27:33–54. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZARUS L.H., PERRIN M.H., BROWN M.R., RIVIER J.E. Mast cell binding of neurotensin. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:7180–7183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE H., SUH B.C., KIM K.T. Feedback regulation of ATP-induced Ca2+ signaling in HL-60 cells is mediated by protein kinase A- and C-mediated changes in capacitative Ca2+ entry. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:21831–21838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZELLA J., BOTTO J.M., GUILLEMARE E., COPPOLA T., SARRET P., VINCENT J.P. Structure, functional expression, and cerebral localization of the levocabastine-sensitive neurotensin/neuromedin N receptor from mouse brain. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5613–5620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05613.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZELLA J., CHABRY J., KITABGI P., VINCENT J.P. Solubilization and characterization of active neurotensin receptors from mouse brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZELLA J., KITABGI P., VINCENT J.P. Molecular properties of neurotensin receptors in rat brain. Identification of subunits by covalent labeling. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:508–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE R.N., OSMAND A.P., DUNN J.A., HOSHI J.G., KOONTZ J.W., ROUSE B.T. Neurotensin regulation of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-stimulated in vitro myelopoesis. J. Immunol. 1989;142:2689–2694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEMEROFF C.B., LEVANT B., MYERS B., BISSETTE G. Neurotensin, antipsychotic drugs, and schizophrenia: basic and clinical studies. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;668:146–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEMBER S.O., SHAPIRA R., KINKADE J.M. Multiple forms of myeloperoxidase from human neutrophilic granulocytes: evidence for differences in compartmentalization, enzymatic activity, and subunit structure. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1983;221:391–403. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHAEFFER P., LAPLACE M.C., PRABONNAUD V., BERNAT A., GULLY D., LESPY L., HERBERT J.M. Neurotensin induces the release of prostacyclin from human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro and increases plasma prostacyclin levels in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;323:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHAEFFER P., LAPLACE M.C., SAVI P., PFLIEGER A.M., GULLY D., HERBERT J.M. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells express high affinity neurotensin receptors coupled to intracellular calcium release. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:3409–3413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIMPFF R.M., GOURMELEN M., SCARCERIAUX V., LHIAUBET A.M., ROSTENE W. Plasma neurotensin levels in humans: relation to hormone levels in diseases involving the hypothalamo-pituitary-thyroid axis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1995;133:534–538. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1330534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOTTE A., LEYSEN J.E., LADURON P.M. Evidence for a displaceable non-specific [3H]neurotensin binding site in rat brain. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1986;333:400–405. doi: 10.1007/BF00500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEO J.K., CHOI S.Y., KIM Y., BAEK S.H., KIM K.T., CHAE C.B., LAMBETH J.D., SUH P.G., RYU S.H. A peptide with unique receptor specificity: stimulation of phosphoinositide hydrolysis and induction of superoxide generation in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 1997;158:1895–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHI W.X., BUNNEY B.S. Actions of neurotensin: a review of the electrophysiological studies. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1992a;668:129–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHI W.X., BUNNEY B.S. Roles of intracellular cAMP and protein kinase A in the actions of dopamine and neurotensin on midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 1992b;12:2433–2438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02433.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA K., MASU M., NAKANISHI S. Structure and functional expression of the cloned rat neurotensin receptor. Neuron. 1990;4:847–854. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VINCENT J.P. Neurotensin receptors: binding properties, transduction pathways, and structure. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1995;15:501–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02071313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VITA N., LAURENT P., LEFORT S., CHALON P., DUMONT X., KAGHAD M., GULLY D., LE FUR G., FERRARA P., CAPUT D. Cloning and expression of a complementary DNA encoding a high affinity human neurotensin receptor. FEBS Lett. 1993;317:139–142. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA M., YAMADA M., WATSON M.A., RICHELSON E. Deletion mutation in the putative third intracellular loop of the rat neurotensin receptor abolishes polyphosphoinositide hydrolysis but not cyclic AMP formation in CHO-K1 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;46:470–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]