Abstract

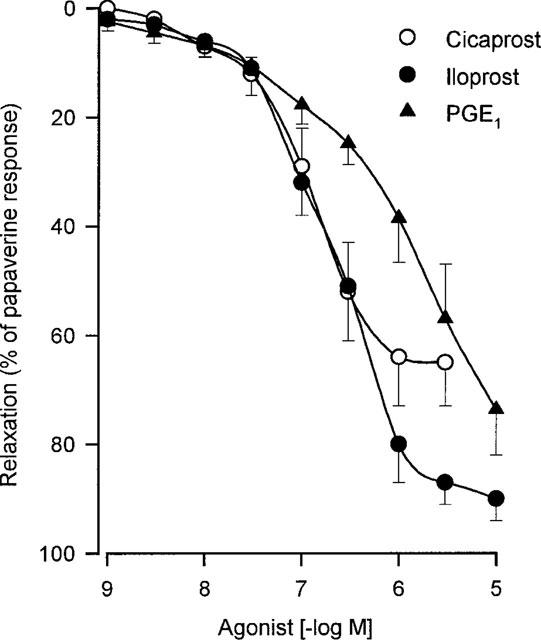

Iloprost and cicaprost (IP-receptor agonists) induced relaxations in the histamine- (50 μM) contracted human bronchial preparations (pD2 values, 6.63±0.12 and 6.86±0.08; Emax values, 90±04 and 65±08% of the papaverine response for iloprost (n=6) and cicaprost (n=3), respectively).

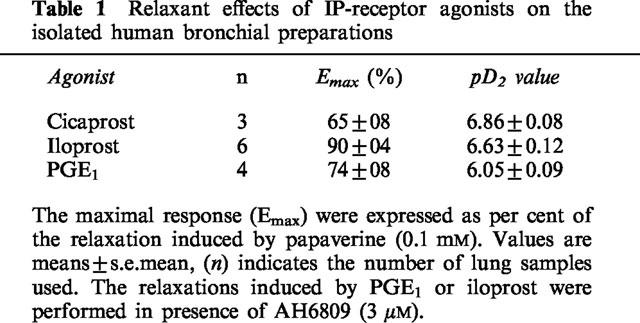

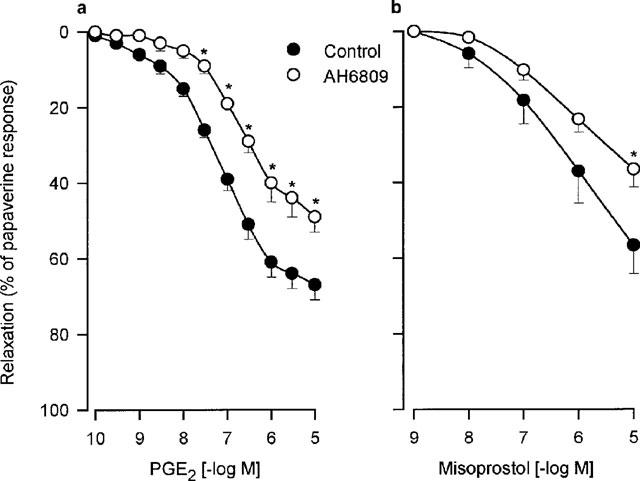

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and misoprostol (EP-receptor agonist) relaxed the histamine-contracted human bronchial preparations (pD2 values, 7.13±0.07 and 6.33±0.28; Emax values, 67±04 and 57±08% of the papaverine response for PGE2 (n=14) and misoprostol (n=4), respectively). In addition, both relaxations were inhibited by AH6809 (DP/EP1/EP2-receptor antagonist; 3 μM; n=5–6).

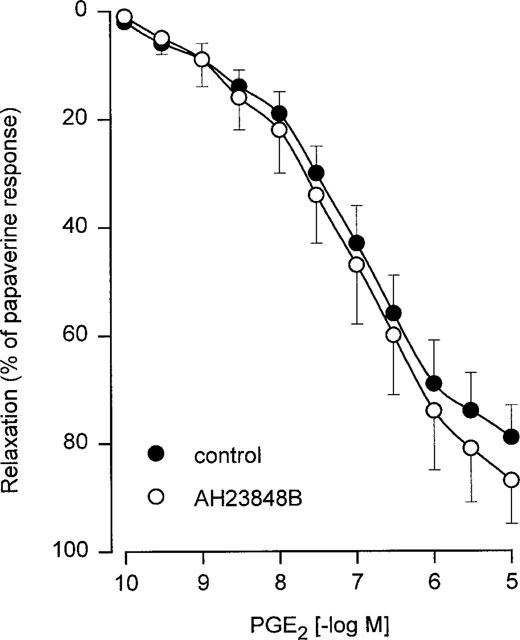

The PGE2-induced relaxations of human bronchial preparations were not modified by treatment with AH23848B (TP/EP4-receptor antagonist; 30 μM; n=4).

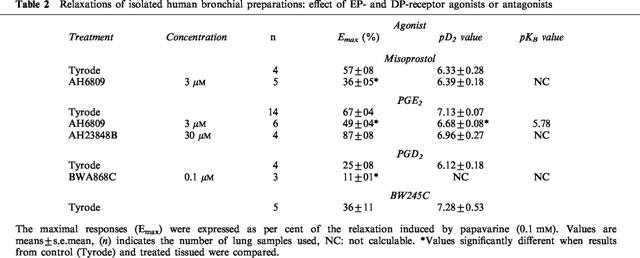

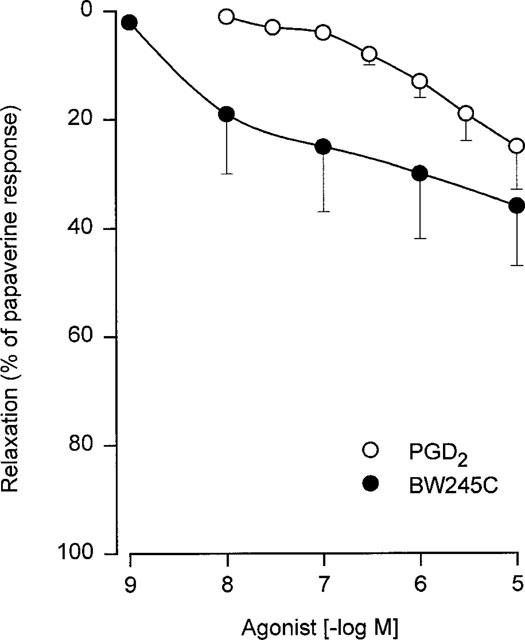

The contracted human bronchial preparations were significantly relaxed by prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) or by BW245C a DP-receptor agonist. However, these responses did not exceed 40% of the relaxation induced by papaverine. In addition, the relaxations induced by PGD2 were significantly inhibited by treatment with a DP-receptor antagonist BWA868C (0.1 μM; n=3).

These data suggest that the relaxation of human isolated bronchial preparations induced by prostanoids involved IP-, EP2- and to a lesser extent DP-receptors but not EP4-receptor.

Keywords: Human bronchial preparations, relaxation, prostanoid receptors, prostaglandin, misoprostol, cicaprost, AH6809, BW245C, BWA868C, AH23848B

Introduction

In asthmatic patients, pretreatment with oral prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) has been shown to prevent the bronchoconstriction to both inhaled histamine and methacholine (Manning et al., 1989). In addition, PGE1 or prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) may attenuate allergen-induced early and late asthmatic response (Pavord et al., 1993; Pasargiklian et al., 1976). These clinical results suggest a role for the EP-receptors in the relaxation of the human airway smooth muscle tone. Most of the pharmacological studies performed in airways derived from animals have demonstrated that the EP-receptors are involved in the prostanoid-induced relaxations. The EP2-receptor has been characterized in the cat trachea (Gardiner & Collier, 1980), while the EP4-receptor has been detected in the rat trachea (Lydford & McKechnie, 1994). Prostacyclin (PGI2) analogues are ineffective as airway muscle relaxants on isolated trachea derived from cat, guinea-pig (Dong et al., 1986) and rat (Lydford & McKechnie, 1994), suggesting no role for the IP-receptor in the relaxation of large airways. In contrast, these PGI2 analogues relax human bronchial preparations (Haye-Legrand et al., 1987). However, the effect of inhaled PGI2 does not alter airway calibre in normal or asthmatic subjects (Hardy et al., 1985; Bianco et al., 1979). Together, the results obtained in these studies suggest that the subtypes of prostanoid-receptors involved in the relaxation of airway smooth muscle vary between species. The DP-receptor and the EP-subtypes have not been systematically investigated in human airways. The aim of the present study was to characterize the different prostanoid receptors involved in relaxation of human bronchial preparations.

Methods

Isolated preparations

Human lung tissues were obtained from patients (26 male and 2 female) who had undergone surgery for lung carcinoma. The mean age was 65±2 years. Bronchial preparations were removed, dissected free from adjoining connective tissue and lung parenchyma, placed in Tyrode's solution (concentration mM): NaCl 139.2, KCl 2.7, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 0.49, NaHCO3 11.9, NaH2PO4 0.4 and glucose 5.5; pH 7.4 and maintained at 4°C. All tissues were used within 1–12 h postsurgery. Bronchial preparations were cut as rings (3–6 mm internal diameter, 3–5 mm in length). The rings were then set up in 10-ml organ baths containing Tyrode's solution, gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2 and maintained at 37°C. An optimal load (2 g) which ensured maximal physiological responses to the agonists used was applied to each ring. Changes in force were recorded by isometric force displacement transducers (Narco F-60) and physiographs (Linseis). Subsequently, preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 90 min with bath fluid changes taking place every 10 min.

Experimental protocol

After the equilibration period, the bronchial preparations were incubated 30 min with BAY u3405 (1 μM), atropine (1 μM), indomethacin (1.7 μM) and 15 min with L-NOARG (0.1 mM). These agents were used to avoid any physiological effects induced by the activation of TP- or muscarinic receptors and by the release of endogenous prostanoids or nitric oxide. When PGE1 or iloprost were used as the relaxant agonist, AH6809 (3 μM) was added to the previous drug combination (30 min) to avoid any physiological effects induced by the activation of EP1-receptors. After incubation, the preparations were contracted with histamine (50 μM), when the response reached a plateau, increasing concentrations of prostanoid receptor agonists (PGE2, PGE1, PGD2, cicaprost, iloprost, BW245C or misoprostol) were applied in a cumulative fashion. The maximal relaxation was obtained for each preparation with papaverine (0.1 mM) at the end of the experiment.

The same protocol was performed to determine the affinity values of prostanoid receptor antagonists (AH23848B, AH6809 or BWA868C) which were added simultaneously with the drug combination during 30 min before the histamine-induced contraction.

Data analysis

The changes in force were measured from isometric recordings and expressed in grams (g). The relaxations produced with the different agonists were expressed as per cent of the relaxations induced with papaverine. The Emax value was the maximal relaxation produced with the highest agonist-concentration used and EC50 value was the concentration which produced Emax/2. These values were interpolated from the individual agonist concentration-effect curves. The pD2 values were calculated as the negative log of EC50 values. When the pD2 values obtained in the presence and absence of an antagonist were significantly different, the equilibrium dissociation constant for the antagonist (KB value) was calculated. The following equation was used: KB=[B]/(DR−1), where [B] is the concentration of the antagonist and DR (dose ratio) is the ratio of EC50 values of agonist in the presence and absence of antagonist. The pKB values were calculated as the negative log of the KB values. All results were expressed as means±s.e.mean of data derived from n different lung samples. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with a confidence level of 95% and taking into account the preparations derived from the same or different lung samples (covariate).

Compounds

PGE2, PGE1, PGD2 and misoprostol ((±)-11, 16-dihydroxy-16-methyl-9-oxoprost-13-en-1-oic acid methyl ester) were purchased from Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A. Iloprost (5-[(E)-(1S,5S,6R,7R)-7-hydroxy-6-[(E)-(3S,4RS)-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-1-octen-6-inyl]bicyclo[3.3.0]-octan-3-ylidene]pentanoic acid) and cicaprost ([-2-[hexahydro-5-hydroxy-4-(3-hydroxy-4-methyl-1,6-nonadinyl)-2-(1H)-pentalenylidene]ethoxy] acetic acid) were a gift from Schering AG, Berlin, Germany. AH6809 (6-isopropoxy-9-oxaxanthene-2-carboxylic acid) and AH23848B ([1α(z),2β,5α]-(±)-7-[5-[[(1,1′-biphenyl)-4-yl]methoxy]-2-(4-morpholinyl)-3-oxo-cyclopentyl]-4-heptenoic acid) were a gift from Glaxo Wellcome, U.K. BAY u3405 (3(R)-3-(4-fluorophenylsulphonamido)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-9-carbazole propanoic acid) was a gift from Bayer, Stokes Poges, U.K. BW245C (5-(6-carboxyhexyl) - 1 - (3 - cyclohexyl - 3 - hydroxypropyl) hydantoin) and BWA868C (3-benzyl-5-(6-carboxyhexyl)-1-(2-cyclohexyl-2-hydroxyethylamino) hydantoin) were a gift from Wellcome Research Laboratories, Beckenham, U.K. Histamine dihydrochloride, L-NOARG (NG-nitro-L-arginine), indomethacin and atropine sulphate were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, U.S.A. Papaverine was obtained from Meram Laboratories (77020 Melun, France).

Results

In each experiment, the human bronchial preparations contracted with histamine (50 μM: 2.37±0.16 g, n=28) and at the end of the protocols the preparations were relaxed with papaverine (0.1 mM: 2.90±0.18 g, n=28). The combination of inhibitors and antagonists (indomethacin, L-NOARG, BAY u3405 and atropine) with which the bronchial preparations were incubated, had no significant relaxant effect on the basal tone of these preparations (−0.06±0.06 g; n=28).

PGE1 as well as two stable PGI2 analogues, iloprost and cicaprost, produced concentration-dependent relaxations (Figure 1 and Table 1) in human bronchial preparations. PGE2 and misoprostol also relaxed the histamine-contracted human bronchial preparations (Figure 2 and Table 2). Concentration-dependent relaxations produced by PGE2 and misoprostol were significantly shifted in presence of AH6809 (3 μM; Figure 2). The pKB value for this antagonist against PGE2 is presented in Table 2. On the contrary, no significant displacement of the relaxation curves induced by PGE2 was observed after an incubation with AH23848B (30 μM, Figure 3 and Table 2). In paired bronchial preparations, derived from the same lung sample, the pD2 values obtained in presence of AH23848B were not statistically different from the control values (6.97±0.11, n=4).

Figure 1.

Relaxation of human isolated bronchial preparations induced by cicaprost, iloprost or PGE1. Responses were expressed as per cent of the papaverine (0.1 mM) relaxation. Values are means±s.e.mean and the number of lung samples used are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relaxant effects of IP-receptor agonists on the isolated human bronchial preparations

Figure 2.

Relaxation of human isolated bronchial preparations induced by PGE2 (a) or misoprostol (b). Some bronchial preparations were treated 30 min with AH6809 (3 μM). Responses were expressed as per cent of the papaverine (0.1 mM) relaxation. In each panel, values are means±s.e.mean and the number of lung samples used are indicated in Table 2. *Values significantly different when results from control (Tyrode) and treated tissues were compared.

Table 2.

Relaxations of isolated human bronchial preparations: effect of EP- and DP-receptor agonists or antagonists

Figure 3.

Relaxation of human isolated bronchial preparations induced by PGE2 in absence or in presence of AH23848B (30 μM). Responses were expressed as per cent of the papaverine (0.1 mM) relaxation. Values are means±s.e.mean derived from four lung samples.

While PGE2, misoprostol, PGE1 and PGI2 analogues totally reversed the histamine contraction, PGD2 and BW245C induced only a partial reversal of this contraction. Concentration-dependent relaxations of human bronchial preparations produced by PGD2 and BW245C are shown in Figure 4 and Table 2. In addition, BWA868C (0.1 μM) significantly reduced the relaxation induced by PGD2 (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Relaxation of human isolated bronchial preparations induced by PGD2 and BW245C. Responses were expressed as per cent of the papaverine (0.1 mM) relaxation. Values are means±s.e.mean and the number of lung samples used are indicated in Table 2.

AH6809, AH23848B and BWA868C at the concentrations used had no significant effect on the basal tone.

Discussion

These data suggest the involvement of IP- and EP2-receptors and to a lesser extent DP-receptor in the relaxant response produced by prostanoids in human airways.

Gardiner & Collier (1980) and Lydford & McKechnie (1994) have demonstrated that in the guinea-pig and in the rat trachea, relaxations induced by the prostanoids are attributed to the activation of EP-receptors. Data (present report) are in contrast to the classical description of prostanoid receptors in the airways derived from animals. Actually, the relaxations induced by cicaprost (IP-receptor agonist; Stürzebecher et al., 1985), indicate the presence of IP receptor in human bronchial preparations. Similar results were obtained with iloprost (EP1/IP-receptor agonist; Schrör et al., 1981; Sheldrick et al., 1988) when the EP1-receptors were blocked by AH6809 (DP/EP1-receptor antagonist; Coleman et al., 1985; Eglen & Whiting, 1988; Keery & Lumley, 1988). These results (present report) are in agreement with data obtained by Haye-Legrand et al. (1987) describing relaxations induced by iloprost, cicaprost (ZK 96480) and PGI2 in the human isolated airways. These authors demonstrated that PGI2, the natural agonist activating IP-receptor, induced quite variable relaxations of the human bronchial preparations. These variations may be due to the short half life of this prostaglandin. Blair & McDermot (1981), Corsini et al. (1987) and Adie et al. (1992) have shown that PGE1, a more stable endogenous prostanoid, is a potent agonist for the IP-receptor in both binding and physiological studies. The effective relaxations of the human bronchi observed with PGE1 (present report) suggest that, this prostaglandin, may be the preferential natural activator for IP-receptor in human airways in vivo.

Kennedy et al. (1982) and Gardiner (1986) have demonstrated that the EP2-receptor is involved in the relaxation of guinea-pig and cat tracheal preparations. These studies were based on the effects induced by butaprost, a PGE1 analogue. In human bronchial preparations, butaprost induced concentration-dependent relaxations (Gardiner, 1986; Norel et al., 1991), these results suggest the presence of EP2-receptor on human airways. Additional evidence consistent with the involvement of the EP2-receptor in the relaxation of human bronchial preparations is suggested by the following observations. First, PGE2 and misoprostol, two preferential agonists for the EP-receptors, were potent airway muscle relaxants. These relaxations cannot be attributed to the activation of the IP-receptor, since these agonists are totally ineffective on the IP-receptor as in human pulmonary arteries (Walch et al., 1999). Misoprostol is a preferential agonist for EP2- and EP3-receptors (Coleman et al., 1988; Reeves et al., 1988; Lydford & McKechnie, 1994). Wise & Jones (1994) showed that this agonist was 10 fold less potent than PGE2 in producing an inhibition of intracellular free calcium in the rat neutrophils (EP2- and IP-receptors). In contrast, Smith et al. (1994) demonstrated that misoprostol was 145 fold less potent than PGE2 for inducing dilatation of the foetal rabbit ductus arteriosus (EP4- and IP-receptors). In human bronchial preparations (present report), misoprostol was only 6 fold less potent than PGE2 in provoking relaxations. Such a ratio is in agreement with the activation of an EP2-receptor when the IP-receptor is present in the same preparation. Secondly, the TP/EP4-receptor antagonist (AH23848B) failed to inhibit the relaxation induced by PGE2, these data suggest that EP4-receptor is probably not involved in the relaxations produced by either PGE2 or misoprostol in human bronchial preparations. Finally, evidence in support of the presence of EP2-receptor is derived from a new effect of AH6809 reported recently (Woodward et al., 1995; Brown et al., 1997) which indicates AH6809 as an EP2 antagonist. The concentration-dependent relaxations induced by both EP agonists (PGE2 or misoprostol) were significantly shifted in presence of this antagonist (present report) suggesting the presence of EP2-receptor.

The human bronchial preparations relaxed to PGD2 and BW245C (present report). These compounds have been described as DP-receptor agonists. Actually, Narumiya & Toda (1985) and Eglen & Whiting (1989) have shown that BW245C is ineffective on the EP2-receptor in the guinea-pig trachea. In a similar fashion, the relaxation induced by PGD2 may not be attributed to the activation of IP-receptors since PGD2 was totally ineffective on human pulmonary arteries (Walch et al., 1999). The involvement of DP-receptors in human bronchial relaxation, is suggested by the 15 fold greater potency of BW245C in comparison with PGD2. This result is in agreement with those obtained by Narumiya & Toda (1985) and Giles et al. (1989) in human washed platelets. Furthermore, the relaxation induced by PGD2 (present report) is significantly reduced in presence of BWA868C a DP-antagonist (Giles et al., 1989). This antagonist does not block the EP2- or IP-receptors as demonstrated by Giles et al. (1989), Chen & Woodward (1992) and Bhattacherjee et al. (1993). Taken together, these results (present report) suggest that PGD2 and BW245C induced relaxations by the activation of DP-receptors. However, these agonists produced relaxations which were less than 50% of the papaverine response. These results suggest a lower density of the DP-receptor or a less effective coupling of this receptor with adenylate cyclase when compared with EP2- or IP-receptors in human airways.

The venous preparations exhibited a similar or a greater sensitivity to the prostanoid-receptor agonists (Walch et al., 1999) than the bronchial preparations (present report). A marked difference was observed with the prostacyclin analogues in bronchial versus pulmonary vascular preparations even though the Emax were the same. These results suggest that there is a difference at the receptorial level between the IP-receptor present in human pulmonary vessels and that in human airways. These data are in agreement with previous reports (Corsini et al., 1987; Armstrong et al., 1989; Merritt et al., 1991; Wise et al., 1995; Takechi et al., 1996) suggesting a heterogeneity of the IP-receptor in various tissues or cells. A comparison of the relaxation induced by PGE2 in the airways (present report) and in the human pulmonary veins (Walch et al., 1999) demonstrates a difference in sensitivity and in maximal relaxations. These differences are consistent with the presence of two different subtypes of EP-receptor in these tissues. While an EP2-receptor is involved in human bronchial preparations, the subtype of EP-receptor involved in venous preparations remains to be characterized.

In conclusion, the results (present report) suggest a major involvement of IP- and EP2-receptors and a minor role for the DP-receptor in the bronchial relaxation induced by the prostanoids in the human lung.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yvette Le Treut and Dominique Gusmini for excellent technical assistance.

References

- ADIE E. J., MULLANEY I., MCKENZIE F.R., MILLIGAN G. Concurrent down-regulation of IP prostanoid receptors and the alpha-subunit of the stimulatory guanine-nucleotide-binding protein (Gs) during prolonged exposure of neuroblastoma x glioma cells to prostanoid agonists. Quantification and functional implications. Biochem. J. 1992;285:529–536. doi: 10.1042/bj2850529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARMSTRONG R.A., LAWRENCE R.A., JONES R.L., WILSON N.H., COLLIER A. Functional and ligand binding studies suggest heterogeneity of platelet prostacyclin receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;97:657–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHATTACHERJEE P., RHODES L., PATERSON C.A. Prostaglandin receptors coupled to adenylyl cyclase in the iris-ciliary body of rabbits, cats and cows. Exp. Eye. Res. 1993;56:327–333. doi: 10.1006/exer.1993.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIANCO S., ROBUSCHI M., GRUGNI A., CESERANI R., GANDOLFI C. Effect of prostacyclin on antigen induced immediate bronchoconstriction in asthmatic patients. Prostaglandins Med. 1979;3:39–45. doi: 10.1016/0161-4630(79)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLAIR I.A., MCDERMOT J. The binding of [3H]-prostacyclin to membranes of a neuronal somatic hybrid. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1981;72:435–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN C.J., BOERSMA J.I., CRANKSHAW D.J. Effects of AH6809 on prostanoid-induced relaxation of human myometrium in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:338P. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN J., WOODWARD D.F. Prostanoid-induced relaxation of precontracted cat ciliary muscle is mediated by EP2 and DP receptors. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1992;33:3195–3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., DENYER L.H., SHELDRICK R.L.G. The influence of protein binding on the potency of the prostanoid EP1-receptor blocking drug, AH6809. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;86:203P. [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., HUMPHRAY J.M., SHELDRICK R.L.G., WHITE B.P. Gastric antisecretory prostanoids: actions at different prostanoid receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;95:724P. [Google Scholar]

- CORSINI A., FOLCO G.C., FUMAGALLI R., NICOSIA S., NOE M.A., OLIVIA D. (5Z)-carbacyclin discriminates between prostacyclin-receptors coupled to adenylate cyclase in vascular smooth muscle and platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;90:255–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb16847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONG Y.J., JONES R.L., WILSON N.H. Prostaglandin E receptor subtypes in smooth muscle: agonist activities of stable protacyclin analogues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:97–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGLEN R.M., WHITING R.L. The action of prostanoid receptor agonists and antagonists on smooth muscle and platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;94:591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGLEN R.M., WHITING R.L. Characterization of the prostanoid receptor profile of enprostil and isomers in smooth muscle and platelets in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;98:1335–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER P.J. Characterization of prostanoid relaxant/inhibitory receptors (ψ) using a highly selective agonist, TR4979. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER P.J., COLLIER H.O.J. Specific receptors for prostaglandins in airways. Prostaglandins. 1980;19:819–841. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(80)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILES H., LEFF P., BOLOFO M.L., KELLY M.G., ROBERTSON A.D. The classification of prostaglandin DP-receptors in platelets and vasculature using BWA868C, a novel, selective and potent competitive antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;96:291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARDY C., ROBINSON C., LEWIS R.A., TATTERSFIELD A.E., HOLGATE S.T. Airway and cardiovascular responses to inhaled prostacyclin in normal and asthmatic subjects. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1985;131:18–21. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYE-LEGRAND I., BOURDILLAT B., LABAT C., CERRINA J., NOREL X., BENVENISTE J., BRINK C. Relaxation of isolated human pulmonary muscle preparations with prostacyclin (PGI2) and its analogs. Prostaglandins. 1987;33:845–854. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(87)90113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEERY R.J., LUMLEY P. AH6809, a prostaglandin DP-receptor blocking drug on human platelets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;94:745–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENNEDY I., COLEMAN R.A., HUMPHREY P.P.A., LEVY G.P., LUMLEY P. Studies on the characterisation of prostanoid receptors: a proposed classification. Prostaglandins. 1982;24:667–689. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(82)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDFORD S.J., MCKECHNIE K. Characterization of the prostaglandin E2 sensitive (EP)-receptor in the rat isolated trachea. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:133–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANNING P.J., LANE C.G., O'BYRNE P.M. The effect of oral prostaglandin E1 on airway responsiveness in asthmatic subjects. Pulm. Pharmacol. 1989;2:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(89)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERRITT J.E., HALLAM T.J., BROWN A.M., BOYFIELD I., COOPER D.G., HICKEY D.M.B., JAXA-CHAMIEC A.A., KAUMANN A.J., KEEN M., KELLY E., KOZLOWSKI U., LYNHAM J.A., MOORES K.E., MURRAY K.J., MCDERMOT J., RINK T.J. Octimibate, a potent non-prostanoid inhibitor of platelet aggregation, acts via the prostacyclin receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:251–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NARUMIYA S., TODA N. Different responsiveness of prostaglandin D2-sensitive systems to prostaglandin D2 and its analogues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;85:367–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb08870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOREL X., LABAT C., GARDINER P.J., BRINK C. Inhibitory effects of BAY u3405 on prostanoid-induced contractions in human isolated bronchial and pulmonary arterial muscle preparations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104:591–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASARGIKLIAN M., BIANCO S., ALLEGRA L. Clinical, functional and pathogenetic aspects of bronchial reactivity to prostaglandins F2 alpha, E1 and E2. Adv. Prostaglandin. Thromboxane. Res. 1976;1:461–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAVORD I.D., WONG C.S., WILLIAMS J., TATTERSFIELD A.E. Effect of inhaled prostaglandin E2 on allergen-induced asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993;148:87–90. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REEVES J.J., BUNCE K.T., SHELDRICK R.L.G., STABLES R. Evidence for the PGE receptor subtype mediating inhibition of acid secretion in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;95:805P. [Google Scholar]

- SCHRÖR K., DARIUS H., MATZKY R., OHLENDORF R. The antiplatelet and cardiovascular actions of a new carbacyclin derivative (ZK36374) equi-potent to PGI2in vitro. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1981;316:252–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00505658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHELDRICK R.L.G., COLEMAN R.A., LUMLEY P. Iloprost a potent EP1 and IP agonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;94:334P. [Google Scholar]

- SMITH G.C., COLEMAN R.A., MCGRATH J.C. Characterization of dilator prostanoid receptors in the fetal rabbit ductus arteriosus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:390–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STÜRZEBECHER C.S., HABEREY M., MULLER B., SCHILLIGER E., SCHRÖDER G., SKUBALLA W., STOCK G.Pharmacological profile of ZK96480, a new chemically and metabolically stable prostacyclin analogue with oral availability and high PGI2 intrinsic activity Prostaglandins and other Eicosanoids in the Cardiovascular System 1985Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 485–491.ed. Schrör, K. pp [Google Scholar]

- TAKECHI H., MATSUMURA K., WATANABE Y., KATO K., NOYORI R., SUZUKI M., WATANABE Y. A novel subtype of the prostacyclin receptor expressed in the central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5901–5906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALCH L., LABAT C., GASCARD J.P. , de MONTPREVILLE V., BRINK C., NOREL X. Prostanoid receptors involved in the relaxation of human pulmonary vessels. MS1: no 980074 submitted to. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:859–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H., JONES R.L. Characterization of prostanoid receptors on rat neutrophils. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:581–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H., QIAN Y.M., JONES R.L. A study of prostacyclin mimetics distinguishes neuronal from neutrophil IP receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;278:265–269. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00173-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOODWARD D.F., PEPPERL D.J., BURKEY T.H., REGAN J.W. 6-isopropoxy-9-oxoxanthene-2-carboxylic acid (AH6809) a human EP2 receptor antagonist. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;50:1731–1733. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]