Abstract

Most current studies of diabetic encephalopathy have focused on brain blood flow and metabolism, but there has been little research on the influence of diabetes on brain tissue and the causes of chronic diabetic encephalopathy. The technique of molecular biology makes it possible to explore the mechanism of chronic diabetic encephalopathy by testing the distribution of somatostatin in the brain. We have therefore analysed, by in situ hybridization histochemistry, the changes in somatostatin (SST) mRNA in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of rats made diabetic by the injection of streptozotocin. Ten Sprague–Dawley control rats were compared with ten streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. The weight, blood glucose and urine glucose did not differ between the two groups before the injection of streptozotocin. Four weeks after the injection of streptozotocin the weight, blood glucose and urine glucose of the diabetic rats were, respectively, 199.1 ± 15.6 g, 23.7 ± 3.25 mmol L−1 and (++) to (+++) whereas those of the control group were 265.5 ± 30.3 g, 4.84 ± 0.63 mmol L−1 and (–). Somatostatin mRNA was reduced in the diabetic rats. The number of SST mRNA-positive neurons and the optical density of positive cells in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of the diabetic rats were 80.6 ± 17.5 mm−2 and 76.5 ± 17.6 compared with 150.5 ± 21.1 mm−2 and 115.1 ± 18.5 in the control rats. The induction of diabetes is thus associated with a decreased expression of SST mRNA in the hippocampus and frontal cortex, which might be an important component of chronic diabetic encephalopathy.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, frontal cortex, hippocampus, somatostatin, rat

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) in adult humans is a global health problem. Although its prevalence varies widely among different peoples, the number of DM patients has generally increased worldwide. There is also a progressive increase in the incidence of diabetes among people reaching old age (Ott et al. 1999). DM impairs tissues and organs causing serious diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy and peripheral neuropathy (Neamat-Allah et al. 2001; Singh et al. 2001; Bailes, 2002). Such diseases have been widely researched, but there has been less study of the effects of diabetes on the central nervous system. Dementia and DM are both common and often coexist in senescence (Luchsinger et al. 2001) and diabetes increases the risk of dementia in general and of Alzheimer's disease (AD) in particular (Ott et al. 1999). Somatostatin (SST) acts through membrane SST receptors (SSTR) (Reynaert et al. 2001). SST in the central nervous system originates not only from the hypothalamus but also from cortical SST neurons. Halonen et al. (2001) report that injection of SST into the lateral ventricle of rats could alleviate memory impairment caused by cysteamine and scopolamine and could restrain extinction of the initiative escape reaction in the jumping stand test. The injection of SST into the hippocampus can enhance long-term potentiation there, and there is much clinical data to show a significant reduction of SST and SST mRNA in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of AD patients (Dutar et al. 2002). All the above studies indicate that SST may play an important role in learning and memory storage in tbe brain. We have therefore studied the distribution of SST mRNA in hippocampal and frontal cortex neurons of control and diabetic rats in order to provide some explanation of why diabetes increases the risk of dementia.

Materials and methods

Animals

Twenty Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 150–200 g were randomly divided into two groups. The rats were weighed, urine was collected, and a blood sample was taken from the caudal vein after the animals were anaesthetized. Plasma glucose was measured using a Glucose Electrode Calibrator (MediSense QA2583-3364) and urine glucose by Test Strips for Urine Glucose (Anjian GZZJ 1-2002). Ten rats were fasted for 10 h then streptozotocin was injected intraperitoneally (60 mg kg−1) to induce diabetes; the remaining ten control rats received an intraperitoneal injection of 0.9% saline. Forty-eight hours after the injection of streptozotocin blood glucose was > 16 mmol L−1 and urine glucose was > (++), indicating the successful induction of diabetes. Blood glucose and urine glucose were then measured weekly in both the control and the diabetic rats. With approval of the local animal care committee (under NIH policies), all efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used.

Four weeks after the injection of streptozotocin all rats were anesthetized with 30 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbitone injected intraperitoneally. The aorta was cannulated and the vascular system washed out with 200 mL normal saline followed by 250 mL 4% paraformaldetyde over 20–30 min. The brain was then removed from the cranial cavity, immersed for 6–8 h in 4% formaldehyde freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde, then immersed in 20% sucrose solution until the tissue sank. Serial frozen sections (about 30 μm thick) were prepared and further fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 4 h.

In situ hybridization

From each group of rats, six sections that contained the same area of frontal cortex and six that contained the same area of hippocampus were chosen. These sections were equilibrated by incubation (2 × 5 min) in Diethyl Pyrocarbonate (DEPC) treated 0.1 m phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 100 mm glycine, then incubated (2 × 5 min) in DEPC-treated PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100. Permeabilized sections were next treated with RNase-free proteinase-K (to increase sensitivity) then refixed in 0.1 m PBS containing 4% formaldehyde and washed (2 × 5 min) with 0.1 m PBS. Sections were acetylated by incubation with triethanolamine (TEA) buffer (2 × 5 min) and overlaid with hybridization buffer (2 × Saline Sodium Citrate (SSC)) containing 0.5 μg mL−1 digitonin-labelled SS-cRNA probe and incubated in a humid chamber at 37 °C. The c. 400-bp sense and anti-sense probes were custom-synthesized by Sigma-Genosys (from The Shanghai second Medical University) and 3′ tailed with digoxin-dUTP (DIG-dUTP) by use of terminal transferase. After 12 h hybridization the sections were washed with 4 × SSC for 15 min, then with 2 × SSC containing RNase A (20 μg mL−1) for 15 min, then with 1 × SSC for 3 × 5 min at 37 °C. DIG-dUTP-labelled oligonucleotide probes were detected after hybridization by enzyme-linked immunoassay using an antibody conjugate (anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, USA). A subsequent enzyme-catalysed colour reaction with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium salt produced an insoluble blue precipitate. The sections were finally washed with 0.05 m PBS (3 × 5 min), coverslipped and examined with an Olympus light microscope. For a further negative control of the hybridization, PBS was used instead of the SST mRNA probe. No stained neurons were seen, whereas using the sense probe revealed blue or purple stained cytoplasm and dendrite.

Image analysis and statistical analysis

The same area of CA3 hippocampus, dentate gyrus and frontal cortex was selected on each slide. The sections were examined at 40× magnification with UTHSCSA Image Tools 3.0 (University of Texas Medical School at San Antonio, TX, USA). The number, optical density and average area of SST mRNA-positive neurons was determined. All data were analysed by the Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are given as mean ± SD.

Results

The weight, blood glucose and urine glucose were not significantly different in the two groups of rats before strepzotocin was injected into one group [controls: weight 173.0 ± 8.6 g, plasma glucose 4.44 ± 0.4 mmol L−1, urine glucose (–); animals to be given streptozotocin: weight 172.3 ± 9.9 g, plasma glucose 4.38 ± 0.55 mmol L−1, urine glucose (–)]. Four weeks after induction of diabetes, the weight of the diabetic animals was 199.1 ± 15.6 g, plasma glucose was 23.7 ± 3.25 mmol L−1 and urine glucose was (++) to (+++) whereas the weight of the control animals was 265.5 ± 30.3 g, plasma glucose was 4.84 ± 0.63 mmol L−1 and urine glucose undetectable (–).

The in situ hybridization study showed that SST mRNA was localized to the cytoplasm and dendrites of cortical neurons, but not in the nucleus. Cells 20–30 μm in diameter were defined as neurons. Many elliptical-shaped SST mRNA-positive neurons were present in the hippocampus, dentate gyrus and frontal cortex of the normal rats. The number and the optical density of SST mRNA-positive neurons were determined in a fixed area of CA3 hippocampus, dentate gyrus and frontal cortex (Figs. 1–6). Table 1 shows a quantitative analysis of the data. There was a significant decrease in the expression of SST mRNA in all three areas studied in the 4-week diabetic rats (Figs. 4–6) compared with that in control rats (Figs. 1–3).

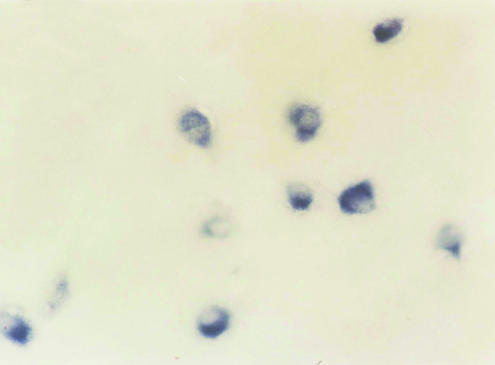

Fig. 1.

SST mRNA intensive positive expression in the normal rat hippocampus (×40).

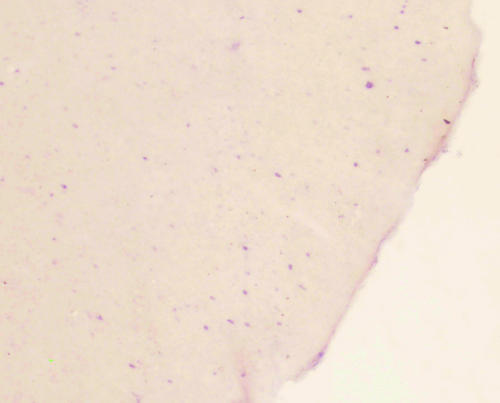

Fig. 6.

Low densities of SST mRNA neurons in the diabetic rat hippocampus(×40).

Table 1.

Comparison of the numbers of SST mRNA-positive neurons in hippocampus and frontal cortex between normal and diabetic rats 4 weeks after inducing the diabetic model (mean ± SD)

| Group | SST mRNA-positive neurons (mm−2) | Light density of SST mRNA-positive neurons |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetic group | 80.6 ± 17.5 | 76.5 ± 17.6 |

| Normal group | 150.5 ± 21.1 | 115.1 ± 18.5 |

P < 0.01.

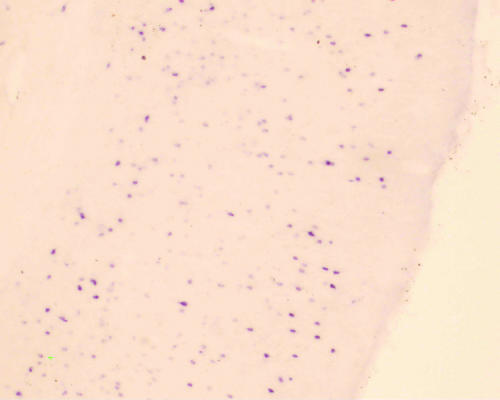

Fig. 4.

SST mRNA neuron in hippocampus of diabetic rat (×40) and low expression of SST mRNA in the frontal cortex of diabetic rat (×40).

Fig. 3.

SST mRNA-positive neuron in the normal rat hippocampus (×400).

Discussion

The study of diabetes-induced functional changes in brain function requires an ideal animal model of diabetes. The intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin alkylates specific bases in DNA, blocks ADP ribosome synthase and destroys the B cells of the pancreas (Balamurugan et al. 2003). There is general agreement that a diabetic rat model should have a normal blood sugar raised over 11.1 mmol L−1 (200 mg dL−1) (Nakagami et al. 2002). This was achieved with our protocol, which caused an increase in blood glucose to 23.7 mmol L−1 48 h after the injection of streptozotocin.

The first somatostatin studied was a 14-amino-acid peptide isolated from ovine hypothalamus and found to inhibit pituitary growth hormone release (Brazeau et al. 1973). Subsequent studies have revealed the existence of numerous forms of SST produced by various tissues (brain, gut, pancreas) that coordinate a vast array of physiological processes including growth, development and metabolism in many different species (Sheridan et al. 2000) and also the cell-specific production of different somatostatins. The first evidence that SST influences memory processes in experimental animals showed that SST administered intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) inhibited the extinction of active avoidance behaviour and had an anti-amnestic effect (Vecsei et al. 1983a, b, 1984). A further experiment showed that the i.c.v. injection of SST could relieve memory impairment induced by cystamine and scopolamine and could restrain extinction of initiative escape reaction in the jumping stand test (Halonen et al. 2001). Matsuoka et al. (1995) found a significant positive correlation between the putative level of cerebral SST and performance in a concurrent discrimination task in an automated morris water radial maze and concluded that central nervous SST plays an important role in learning and memory. In many AD patients SST, SST mRNA and SST receptors are significantly decreased in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex (Davis et al. 1999; Van-Uden et al. 1999; Nilsson et al. 2001). Central nervous system SST is also thought to be involved in other dementias such as frontotemporal dementia and HIV encephalitis (Barnea & Roberts, 1999; Braun et al. 2002). Reduction of cortical SST receptors and in all these studies indicates that SST plays an important role in learning, storing and retention of information in the brain and therefore in normal cognition.

The data presented here show that SST mRNA and, by implication SST peptide, is significantly reduced in the hippocampus, dentate gyrus and frontal cortex of streptozotocin-diabetic rats. The amount of SST mRNA per cell appeared to have declined considerably, based on the optical density of the hybridization reaction. The number of neurons in which SST mRNA could be detected also declined considerably. The results clearly indicate that hyperglycaemia induced by streptozotocin reduces the expression of SST in the hippocampus and frontal cortex, two key regions of the central nervous system for memory and cognition. A similar decline in cerebral SST in human diabetic patients could be a part of the reason why diabetes increases the risk of dementia.

Fig. 2.

SST mRNA intensive positive expression in the normal rat frontal cortex (×40).

Fig. 5.

SST mRNA expression in frontal cortex of diabetic rat (×40).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Yaoming Zhang and Zhenghua Xiang for their expert technical assistance. This research was supported by the Health Bureau of Zhejiang Province (No. 2002B022).

References

- Bailes BK. Diabetes mellitus and its chronic complications. AORN-J. 2002;76:266–276. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61065-x. 278–282; quiz 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan V, Kataria JM, Kataria RS, Verma KC, Nanthakumar T. Streptozotocin (STZ) is commonly used to induce diabetes in animal models. Pancreas. 2003;26:102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea J, Roberts RH. Ho, Evidence for a synergistic effect of the HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) leading to enhanced expression of somatostatin neurons in aggregate cultures derived from the human fetal cortex. Brain Res. 1999;815:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun H, Schulz SV, Hollt V. Expression changes of somatostatin receptor subtypes sst2A, sst2B, sst3 and sst4 after a cortical contusion trauma in rats. Brain Res. 2002;930:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazeau P, Vale W, Burgus R. Hypothalamic polypeptide that inhibits the secretion of immunoreactive pituitary growth hormone. Science. 1973;179:77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4068.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, Mohs RC, Marin DB, Purohit DP, Perl DP, Lantz M, et al. Neuropeptide abnormalities in patients with early Alzheimer's disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1999;56:981–987. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.11.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutar P, Vaillend C, Viollet C, Billard JM, Potier B, Carlo AS, et al. Spatial learning and synaptic hippocampal plasticity in type 2 somatostatin receptor knock-out mice. Neuroscience. 2002;112:455–466. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halonen T, Nissinen J, Pitkanen A. Effect of lamotrigine treatment on status epilepticus-induced neuronal damage and memory impairment in rat. Epilepsy Res. 2001;46:205–223. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Stern Y, Shea S, Mayeux R. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer's disease and dementia with stroke in a multiethnic cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001;154:635–641. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka N, Yamazaki M, Yamaguchi I. Changes in brain somatostatin in memory-deficient rats: comparison with cholinergic markers. Neuroscience. 1995;66:617–626. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00628-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami T, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, Balkau B, Carstensen B, Tajima N, et al. The fasting plasma glucose cut-point predicting a diabetic 2-h OGTT glucose level depends on the phenotype. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2002;55:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(01)00270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neamat-Allah M, Feeney SA, Savage DA, Maxwell AP, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, et al. Analysis of the association between diabetic nephropathy and polymorphisms in the aldose reductase gene in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2001;18:906–914. doi: 10.1046/j.0742-3071.2001.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson CL, Brinkmalm A, Minthon L, Blennow K, Ekman R. Processing of neuropeptide Y, galanin, and somatostatin in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Peptides. 2001;22:2105–2112. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00571-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott A, Stolk RP, van-Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia. The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1999;53:1937–1942. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaert H, Vaeyens F, Qin H, Hellemans K, Chatterjee N, Winand D, et al. Somatostatin suppresses endothelin-1-induced rat hepatic stellate cell contraction via somatostatin receptor subtype 1. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:915–930. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, Kittilson JD, Slagter BJ. Structure–function relationships of the signaling system for the somatostatin peptide hormone family. Am. Zool. 2000;40:269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Behre A, Singh MK. Diabetic retinopathy and microalbuminuria in lean type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Ass. Physicians India. 2001;49:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van-Uden E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Orlando R, Masliah E. A novel role for receptor-associated protein in somatostatin modulation: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 1999;88:687–700. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Bollok I, Telegdy G. Intracerebroventricular somatostatin attenuates electroconvulsive shock-induced amnesia in rats. Peptides. 1983a;4:293–295. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(83)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Bollok I, Telegdy G. The effect of linear somatostatin on active avoidance behavior and open-field activity on haloperidol, phenoxybenzamine and atropine pretreated rats. Acta Physiol. Hung. 1983b;62:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Bollok I, Varga J, Penke B, Telegdy G. The effects of somatostatin, its fragments and an analog on electroconvulsive shock-induced amnesia in rats. Neuropeptides. 1984;4:137–143. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(84)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]