Abstract

The receptor, c-kit, and its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), are important regulators of ovarian follicle growth and development. The aim of this study was to identify the sites of expression of mRNA for c-kit and SCF in prepubertal and mature (pregnant and non-pregnant) animals. Ovaries were recovered from prepubertal animals, non-pregnant sows and five sows at approximately 3 months of gestation. Ovine SCF and c-kit DNA were cloned into plasmid vectors to produce RNA probes. Expression of mRNA encoding SCF and c-kit were detected via in situ hybridization. Both mRNA were detected throughout ovaries from all animals. This study provides evidence that the growth-factor complex is required throughout follicle development, and also for continued maintenance of the corpus luteum (CL) in the mature animal. SCF mRNA was localized to the granulosa cell layer and was also extensively expressed in endothelial tissue and throughout the CL. c-kit mRNA was detected in the theca layer, oocytes and also in CL. In conclusion, expression of SCF and c-kit mRNA in granulosa and theca cells, respectively, indicate an important interaction between somatic cells throughout follicle development and that in the mature animal, SCF and c-kit potentially have a role in maintaining progesterone secretion by the CL. The observations of continued expression of SCF and c-kit throughout development suggest that there may be differences in the role of this receptor–ligand complex between large mono- vs. poly ovulatory species, such as the pig.

Keywords: angiogenesis, corpus luteun, follicle, granulosa cell, pig

Introduction

The c-kit ligand complex is a pleiotropic receptor–growth factor complex active in diverse cell systems in both the adult and the embryo (Horie et al. 1991). Mutations at both these loci give rise to defects in the proliferation, migration and differentiation of stem cells in the melanogenic, gametogenic and hematopoietic lineages (Besmer, 1991). Studies in mice have demonstrated that the receptor, c-kit, and its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), are important regulators of ovarian follicle growth and development, in both the mature (Yoshida et al. 1997) and the immature animal (Horie et al. 1991; Manova et al. 1993). Internal SCF (ISCF) is a short isoform of the full-length SCF molecule and codes for both the transmembrane and the soluble variants of SCF (M. F. Smith, personal communication). In the fetus, it has been proposed that the interaction between c-kit and SCF is necessary for germ cell migration in mice (Keshet et al. 1991) and for the prevention of germ cell apoptosis in sheep (Tisdall et al. 1999). Postnatally, the receptor–ligand interaction may aid follicle recruitment into the pool of growing follicles (Parrott & Skinner, 1999) and be involved in follicle development through to ovulation (Ismail et al. 1999). Data obtained in sheep (Tisdall et al. 1997) show that c-kit and SCF expression continues throughout follicular development, suggesting that their interaction is relevant during later stages of follicle growth. However, in mice, although c-kit is expressed in oocytes throughout follicle development, SCF mRNA expression has been shown to be highest in granulosa cells from preantral follicles but declines as follicles develop up to late antral stage (Motro & Bernstein, 1993; Joyce et al. 1999). c-kit and ligand mRNA levels dynamically and dramatically change in both space and time during the oestrous cycle (Motro & Bernstein, 1993). In ovine follicles, c-kit is expressed before the follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor, suggesting that c-kit may be one of the regulatory factors preceding the actions of FSH on early follicle growth (Clark et al. 1996). Yoshida et al. (1997) demonstrated that c-kit and its ligand are required for distinct steps of ovarian follicle development in the mouse. It has recently been elucidated that SCF and its interaction with c-kit play a role in antrum formation, steroidogenesis and oocyte quality (Reynaud et al. 2000). Joyce et al. (1999) observed that SCF mRNA expression in mouse follicles was controlled by the oocyte depending upon the stage of its growth and development. The nature of such control factors remains to be elucidated, but highlights the role of SCF during follicle growth in vivo. For example, theca cells and oocytes may be sources of soluble c-kit.

SCF mRNA has been localized within day 3 and day 10 ovine corpus luteum (CL), and SCF was expressed in a cell-specific manner in cells with the morphological characteristics of luteal cells (Gentry et al. 1996). Thus it may have a role in steroidogenesis (Parrott & Skinner, 1997) and in communication between small and large luteal cells (Gentry et al. 1996).

The effect of SCF in porcine granulosa and theca cell cultures (Brankin et al. 2003) and in other species (Parrott & Skinner, 1997; Magoffin et al. 1999; Huang et al. 2001) has demonstrated an important role for SCF in both cellular differentiation and steroidogenesis. However, there is a paucity of information on both the pattern of mRNA expression and the role of SCF and c-kit in ovaries of large multi-ovulatory species such as the pig. The aims of the current study were to identify the sites of expression of mRNA for c-kit, SCF and ISCF. The study also investigated the changes in distribution of receptor and ligand expression in relation to stages of follicle development and importantly to compare patterns of expression between both prepubertal and mature (non-pregnant and pregnant) animals. In the prepubertal animal there would be a larger number of pre- and early antral follicles. In the mature animal the ovaries would contain a larger number of pre-ovulatory follicles and newly formed CLs, whereas in the pregnant animal there would be no large pre-ovulatory follicles, but the presence of well-established CLs.

Materials and methods

All reagents were purchased from Sigma, Poole, UK. unless otherwise stated.

Tissue collection and preparation

Porcine ovaries were collected from a local slaughterhouse. Ovaries were recovered from five sows at approximately 3 months of gestation (estimated by fetal crown rump length); five non-pregnant sows (mid-follicular phase) and five prepubertal animals (determined by the absence of CL). Each ovary was dissected into approximately 1-cm3 blocks, the number and size of follicles recorded and frozen within 1 h of slaughter in liquid nitrogen using OCT compound (Agar, Stansted, UK) as the embedding medium. The blocks were stored at −80 °C until required for sectioning.

Sections 10 µm thick were cut from each block using a Bright Cryostat set at −31 °C. For each animal, between 20 and 30 sections were cut and 2–3 sections were placed on poly-l-lysine-coated slides. The sections were air dried for 30 min and stored at −80 °C until required for hybridization.

mRNA probe preparation

Plasmid preparation

SCF, ISCF and c-kit plasmid stocks were a gift from Professor M. F. Smith at the University of Missouri, Columbia, USA. Ovine stem cell factor cDNA (952-bp insert) was cloned into the pBluescript SK (–) vector (Stratagene Ltd, Cambridge, UK). Ovine ISCF cDNA (326-bp insert) and ovine c-kit cDNA (623-bp insert) were cloned into pCRII vectors (Invitrogen BV, The Netherlands). The plasmid stocks were stored in glycerol at −80 °C.

Each plasmid was plated and grown overnight at 37 °C on ampicillin-resistant L-agar (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). A colony from each plasmid preparation was grown in L-broth (Invitrogen) for 8 h at 37 °C. A small aliquot was removed from each primary culture and a secondary culture incubated at 37 °C overnight.

The plasmid DNA was purified using the Promega Wizard Plus Maxiprep System (Promega, Southampton, UK). The resultant DNA pellet was resuspended in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Wizard Maxiprep DNA purification resin was added, transferred to a Maxicolumn and the DNA resin was drawn through the column under a vacuum. The resultant column was centrifuged at 1300 g for 5 min. Prewarmed water (65 °C) was used to elute the DNA via centrifugation (1300 g for 5 min). The eluate was syringe filtered and aliquoted in 100-µL units and stored at −20 °C.

The concentration and quality of plasmid DNA was determined by UV spectrophotometry assuming 1.0 optical density unit represents 50 µg mL−1 DNA and that the purity of DNA can be represented by the following: Optical densityλ260÷ Optical densityλ280.

DNA template preparation

Each plasmid DNA was linearized using appropriate restriction endonucleases: c-kit, EcoRV and BamHI; SCF, XhoI and NotI; ISCF, EcoRV and BamHI. The reaction mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Each cut plasmid preparation was examined by gel electrophoresis, using 1% seaplaque agarose low-melting-point gel (Flowgen, Ashby de la Zouch, UK) to ensure the plasmid preparations were linearized.

DNA purification

The plasmid DNA containing bands on the gel were cut away, agarose melted and the DNA was cleared by phenol extraction. The DNA was extracted using phenol/chloroform/isoamylalcohol (PCI) 25 : 24 : 1 and finally with chloroform/isoamylalcohol (CI) 24 : 1. The plasmid DNA was precipitated with ethanol, washed with further ethanol and resuspended in 20 µL prewarmed Proteinase-K buffer (1 mg mL−1). The DNA was extracted as before using PCI, PI and finally with ethanol. The resultant suspension was frozen for 30 min and microfuged for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water and stored at −20 °C. The plasmid samples were analysed by gel electrophoresis and the concentration of DNA was measured as before.

The integrity and orientation of the probes were verified by dideoxy DNA sequencing and the resultant sequences compared to sequences on the EMBL database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk).

In vitro transcription

Sense and antisense RNA probes were transcribed from the template DNA using appropriate polymerases and labelled using fluorescein-12-UTP. All reagents used for the transcription procedure were purchased from Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, East Sussex, UK. Briefly, purified, linearized plasmid DNA was added to 10× concentrated fluorescein labelling mix and 10× transcription buffer, appropriate polymerase and DEPC-treated water. The reaction mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. EDTA was added to stop the reaction and the labelled transcript was precipitated using a QIAquick Nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA concentration was measured by UV spectrophotometry. The probe solution was stored at −80 °C until required for hybridization.

In situ hybridization

Frozen sections were fixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, acetylated in 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 m triethanolamine for 10 min and then dehydrated through 70, 90 and 100% ethanol. The prepared RNA probes were diluted in hybridization buffer (0.1% Denhardt's solution, 25% formamide, 3× SSC, 500 µg mL−1 salmon sperm DNA, 500 µg mL−1 tRNA and 10% dextran sulphate) to 1 ng µL−1.

The diluted probes were heated to 80 °C for 5 min, mixed and applied to the section. Approximately 20 µL was sufficient to cover each section. The sections were hybridized overnight at 65 °C in a humidified chamber. For each animal, two sections were hybridized with the antisense probe and one section was hybridized with the sense probe (control).

Post-hybridization washes were as follows: formamide wash at 50 °C for 90 min; NTE buffer (0.5 m NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl 1 mm EDTA) at 37 °C for 2 × 5 min; RNase A at 37 °C for 30 min; NTE buffer at 37 °C for 2 × 5 min; a second formamide wash for a further 90 min and finally, slides were washed in 1 × SSC (20× SSC: 3 m NaCl and 0.3 m sodium citrate) for 5 min. The sections were dehydrated and left to air dry. The sections were mounted in PBS/glycerol (1 : 9) with antifade (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, Cambridgshire, UK).

Sections were evaluated by fluorescence microscopy. Images were captured using the Optimas (Bioscan, Edmonds, WA, USA) image analysis package. For each large follicle and CL four fields of view at 90° angles were observed. The number of observations were as follows: for prepubertal animals a minimum of 40 and 80 observations were made for follicles < 2 mm and > 2 mm, respectively. For mature animals a minimum of 40, 70 and 10 observations were made for follicles < 2 mm, > 2 mm and CLs, respectively. For pregnant animals a minimum of 10, 50 and 10 observations were made for follicles < 2 mm, > 2 mm and CLs, respectively. Following image capture the sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and viewed via light field microscopy.

Results

Follicle classification

The sequence homology for ovine SCF, ISCF and c-kit DNA was 92.7, 91.4 and 89.1%, respectively, for porcine SCF, ISCF and c-kit. Hybridization of sections to the sense probe resulted in a signal similar to non-expressing regions of the sections hybridized with the antisense probe. The use of antisense probes therefore produced tissue-specific signals. Specific positive staining for each probe was observed across all five animals in each developmental group.

In situ hybridization signals were captured from five ovaries at each developmental stage. For each section of mature (non-pregnant) tissue, large-sized (> 6 mm), medium-sized (2–6 mm) and small-sized (< 2 mm) follicles were analysed. Only medium- (2–6 mm) and small-sized (< 2 mm) follicles were present and assessed in mature (pregnant) tissue. In addition, CL and a range of connective supporting tissue were analysed from each section. Pre-antral, small- (< 2 mm) and medium-sized (2–6 mm) follicles and connective tissue were analysed in sections from prepubertal animals. The mean number of follicles per section was also assessed. In maternal tissue there was an average of one follicle (< 2 mm), five follicles (> 2 mm) and one CL per section. In prepubertal tissue, there was an average of four follicles (< 2 mm) and eight follicles (> 2 mm) per section. In sow tissue, there was an average of four follicles (< 2 mm), seven follicles (> 2 mm) and one CL per section. These findings were for tissue subjected to all three probes. Follicles were deemed healthy where a compact layer of granulosa cells was evident. Follicles were classed as atretic when the granulosa cells were shed from the basement membrane into the antrum (Bagavandoss et al. 1983; Junquiera et al. 1989).

SCF, ISCF and c-kit mRNA expression in mature ovarian tissue

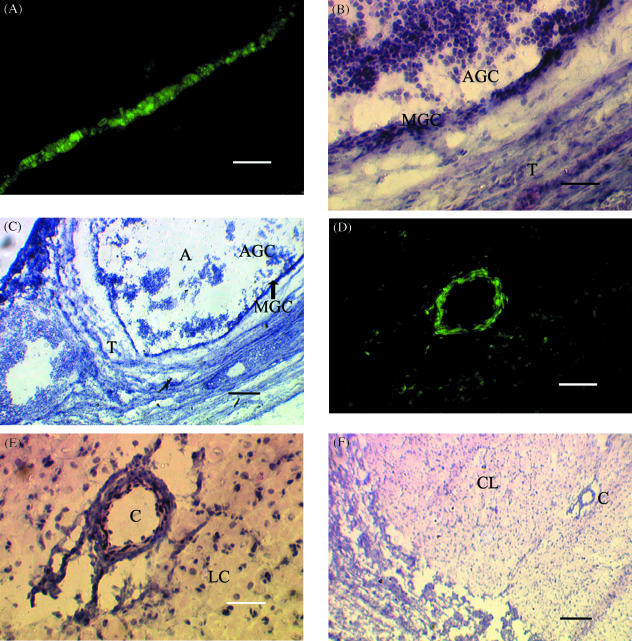

Follicle size was limited to < 7 mm in all sections from pregnant animals. SCF mRNA was localized to mural granulosa cells in small- (< 2 mm) and medium-sized (2–6 mm) follicles (Fig. 1A) in ovarian tissue from pregnant animals. This pattern of expression was observed in healthy and atretic follicles (where granulosa cells were loosely attached to the basement membrane and/or shed into the antrum). mRNA-encoding SCF was also localized in endothelial tissue within the CL (Fig. 1D) and within luteal cells (Fig. 2A). However, SCF mRNA was detected only in granulosa cells attached to the basement membrane (Fig. 2C). In non-pregnant mature animals, a similar pattern of SCF expression was observed with abundant signal in both healthy granulosa cells in medium-sized follicles and throughout the stromal tissue. Weak expression was also noted in CL, but it was not possible to identify the exact cell type expressing SCF. Because ISCF encodes for a shorter, cleaved soluble isoform of SCF, it is not surprising that the expression patterns were very similar to that for SCF. Therefore, ISCF acted as an internal control (Gentry et al. 1996), confirming the sites of localization for SCF.

Fig. 1.

Localization of stem cell factor (SCF) mRNA expression in (A–C) mural granulosa cells from a medium-sized (2–6 mm) follicle and (D–F) endothelial tissue within the CL. (A,D) Dark field illumination (×100) of a 10-µm section of ovarian tissue from a pregnant animal probed with fluorescein-labelled antisense SCF mRNA. (B, C, E, F) Light field illumination of sections A and D stained with haematoxylin and eosin (×100 and ×40, respectively). MGC, AGC, T, A, C, LC and CL represent mural granulosa cells, atretic granulosa cells (shed into the antrum), theca, antrum, capillary, luteal cells and CL, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm at ×100 and 100 µm at ×40.

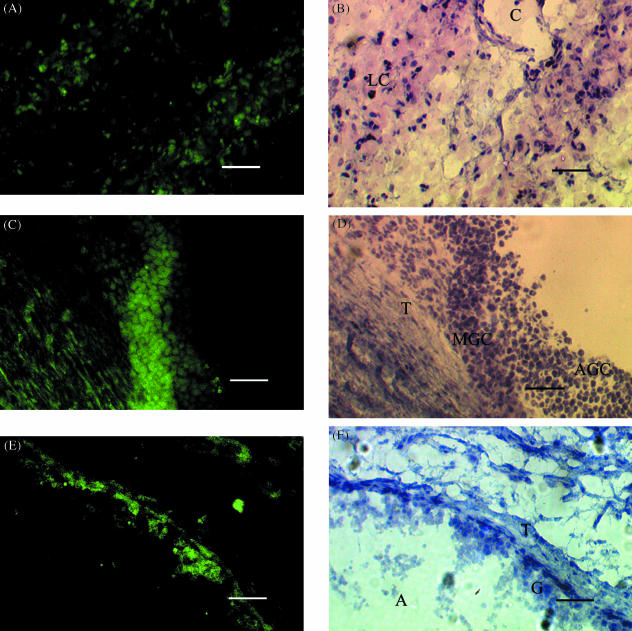

Fig. 2.

Localization of stem cell factor (SCF) mRNA expression in (A, B) luteal cells and (C, D) mural granulosa cells from a medium-sized (2–6 mm) follicle. (A, C) Dark field illumination (×100) of 10-µm sections of ovarian tissue from a pregnant animal probed with fluorescein-labelled antisense SCF mRNA. (B, D) Light field illumination of sections A and C, respectively, stained with haematoxylin and eosin (×100). (E, F) Localization of c-kit mRNA expression in the theca layer of a medium-sized (2–6 mm) follicle. (E) Dark field illumination (×100) of 10-µm sections of ovarian tissue from a pregnant animal probed with fluorescein-labelled antisense c-kit mRNA. (F) Light field illumination of section E stained with haematoxylin and eosin (×100). C, LC, T, MGC, AGC, A, and G represent capillary, luteal cells, theca, mural granulosa cells, atretic granulosa cells, antrum and granulosa cells, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm.

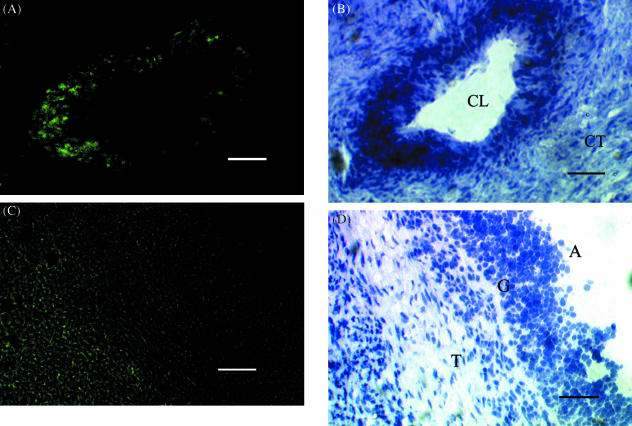

c-kit mRNA was expressed in endothelial tissue within the CL in a similar pattern to that shown by SCF mRNA. Signal for c-kit mRNA was also detected in the theca cell layer of small- and medium-sized follicles (Fig. 2E) and throughout the CL in large luteal cells (Fig. 3A). This pattern of expression was also consistent in follicles from non-pregnant animals. Interestingly, there was a strong gradient of expression across the theca layer in large (> 6 mm) follicles, with the strongest signal being observed in the theca externa in non-pregnant animals (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Localization of c-kit mRNA expression in the CL (A, B); the theca externa layer (C, D). (A, C) Dark field illumination (×100) of 10-µm sections of ovarian tissue from a pregnant and non-pregnant animal, respectively, probed with fluorescein-labelled antisense c-kit mRNA. (B, D) Light field illumination of sections A and C stained with haematoxylin and eosin (×100), respectively. CL, CT, T, A and G represent corpus luteum, connective tissue, theca, antrum and granulosa, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm.

SCF, ISCF and c-kit mRNA expression in prepubertal ovarian tissue

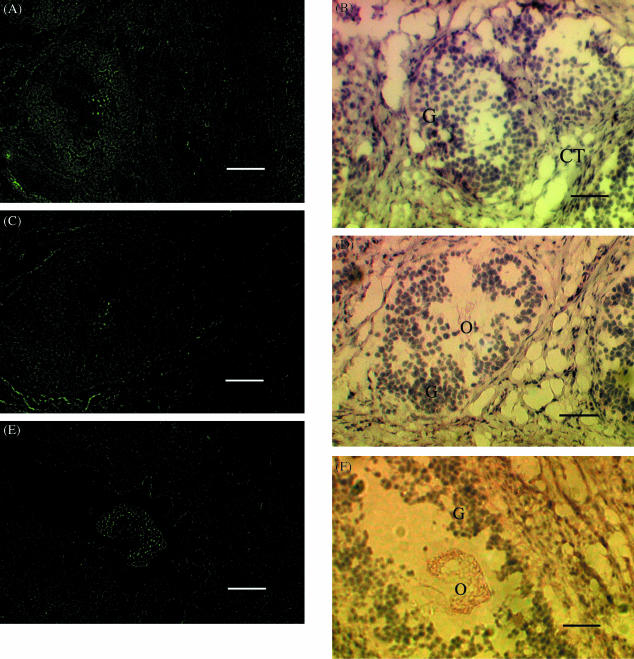

Follicle size was limited to < 4 mm in all sections from prepubertal animals. SCF mRNA was localized to the granulosa cell layer of both preantral (Fig. 4A) and early antral follicles (Fig. 4C). ISCF mRNA expression appeared to be weaker compared with mature tissue and was located exclusively to the granulosa cell layer.

Fig. 4.

Localization of (A) stem cell factor (SCF) mRNA expression in the granulosa cells of a preantral follicle; (C, E) c-kit mRNA expression in the oocyte in an early antral follicle. (A, C, E) Dark field illumination (×100) of 10-µm sections of prepubertal ovary probed with fluorescein-labelled antisense SCF mRNA and c-kit mRNA, respectively. (B, D, F) Light field illumination of sections A, C and E, respectively, stained with haematoxylin and eosin (×100). G, CT and O represent granulosa, connective tissue and oocyte, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm.

c-kit mRNA expression in prepubertal ovaries was similar to that observed in ovaries from mature sows. Signals were detected in the theca cell layer and endothelial tissue, although gradients of expression from the theca interna to the theca externa were not observed. However, c-kit mRNA was detected in the oocyte, although expression was weak (Fig. 4E). Similar patterns of expression were also observed in primary and early antral follicles. The patterns of expression for c-kit and SCF mRNA in ovaries from prepubertal, mature and pregnant animals are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Localization of c-kit and SCF mRNA according to follicle status in prepubertal, mature (non-pregnant) and mature (pregnant)

| Prepubertal | Mature (sow) | Mature (pregnant) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell type | c-kit | SCF | c-kit | SCF | c-kit | SCF |

| Oocyte | ++†* | – | / | / | / | / |

| Granulosa cells | – | ++†* | – | +++* | – | +++* |

| Theca cells | ++* | – | +++‡ | – | +++* | – |

| Corpus luteum | / | / | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Vascular network | +++ | +/– | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Connective tissue | nd | nd | – | ++ | – | +/– |

SCF, stem cell factor; +, signal weakly positive; ++, signal moderate; +++, signal strong; † pre-antral follicles; * small- and medium-sized follicles (≤ 4 mm prepubertal and < 6 mm mature); ‡ small, medium and large follicle sizes (< 8 mm); /, cell types absent from sections; nd, non-detectable mRNA signal; –, not expressed; +/–, not always expressed.

Discussion

The mechanisms responsible for follicle recruitment, growth, maturation and ovulation are not fully understood. Although the expression patterns of c-kit and SCF have been studied in other species, no information about these expression patterns in the porcine ovary have been published. This study has demonstrated that the porcine ovary, throughout all stages of development, expresses mRNA for SCF, ISCF and receptor, c-kit. The probe for SCF contained cDNA for both transmembrane and soluble forms of SCF. The results demonstrated that SCF mRNA was detected in mural granulosa cells of small- and medium-sized follicles in adult animals, suggesting that SCF may have a different role in poly-ovulatory species such as the pig compared with mono-ovulatory species.

These findings are similar to ovine studies (Tisdall et al. 1997). However, Tisdall et al. (1997) observed that in adult ovine ovaries, ovine SCF mRNA could be detected in the granulosa cells at all stages of follicle growth. Joyce et al. (1999) observed that the levels of mouse SCF mRNA were high in granulosa cells from preantral follicles, but declined after antrum formation. Furthermore, the converse was observed in bovine granulosa cells (Parrott & Skinner, 1997) where SCF mRNA levels were greatest in granulosa cells from large-sized follicles.

SCF mRNA was also observed in granulosa cells of preantral and early antral follicles in prepubertal ovaries. It has been suggested that SCF is necessary for early follicle development, particularly granulosa cell development, in mice (Bedell et al. 1995). Depressed SCF expression at this stage can arrest oocyte growth, which in turn, via oocyte-secreted signals, inhibits granulosa cell growth. However, in contrast, Manova et al. (1993) observed that SCF mRNA expression was low in follicle cells of small growing mouse follicles, but increased to higher levels in three layered follicles. These findings demonstrate the need for SCF mRNA expression to be studied throughout postnatal development.

SCF mRNA was also isolated to porcine luteal cells and to endothelial tissue throughout the CL, in tissue from both pregnant and non-pregnant animals. This suggests an interaction, which may promote differentiation and development of luteal cells, and possibly demonstrates an interaction between small and large luteal cells. There is also the possibility that SCF mRNA may be co-expressed in the granulosa–lutein cells as the luteal cell type where expression was found could not be determined. This warrants further investigation, but it is interesting to note that in sheep, SCF is expressed in both large and small luteal cells (Gentry et al. 1996). Because the porcine CL grows rapidly and is responsible for secreting large amounts of progesterone, SCF may play a role in the differentiation of luteal cells and therefore in the maintenance of pregnancy. Our in vitro studies have demonstrated previously that hSCF had a role in granulosa and theca cell differentiation, which may be directly related to steroid synthesis (Brankin et al. 2003). Further studies to identify luteal cell markers are required to determine the type of luteal cell that expresses SCF mRNA and the expression pattern at different stages of pregnancy. It would also be interesting to determine if the levels of expression of SCF throughout pregnancy reflect the levels of steroid synthesis by the CL. It has been documented that accompanying the rapid growth of the CL, dynamic changes in luteal vascularity also occur throughout development (Zheng et al. 1993). Hence, expression of SCF mRNA in endothelial tissue within the CL may have a role in CL growth and development.

ISCF mRNA localization was similar to that for SCF mRNA in that it was expressed in granulosa cells attached to the basement membrane, but also expressed in atretic granulosa cells shed into the antral space. Expression was also observed in endothelial tissue as observed for SCF mRNA. This is the expected expression pattern, as the ISCF probe contained the sequence for the transmembrane domain and should detect both the membrane and the soluble forms of SCF (M. F. Smith, personal communication). ISCF mRNA was isolated to vascular tissue within CL. This again suggests that the expression of both SCF and ISCF may play a role in supporting the CL of pregnancy.

Having localized the expression of SCF mRNA, it was also necessary to determine the expression sites of its receptor, c-kit, in order to elucidate the action of the receptor–ligand complex. The probe for c-kit was a 632-bp cDNA encoding most of the ligand-binding domain. c-kit mRNA was detected in both the theca externa and the theca interna cell layer. This is in agreement with studies in mice (Motro & Bernstein 1993) and cattle (Parrott et al. 1997). A strong signal was observed in the theca externa in follicles from non-pregnant mature animals. The gradient of expression of c-kit mRNA in the theca externa suggests that because the theca externa is composed mainly of smooth muscle and collagen, c-kit may play a role in either maintenance of the structural integrity of the follicle or ovulation, whereby the theca externa is degraded by collagenases (Parrott et al. 2000).

Because SCF mRNA was localized to the granulosa layer and c-kit to the theca layer, this suggests that there is a theca–granulosa layer interaction, as with steroidogenesis (Falk, 1959; Evans et al. 1981; Tsang et al. 1985). This finding is supported by in vitro studies (Brankin et al. 2003), in which hSCF at doses of 10 and 100 ng mL−1 modulated steroid production in both theca and granulosa cell cultures, but was attenuated when cells were cultured together. It has been suggested that this interaction may be beneficial to small growing follicles (Tisdall et al. 1997). However, as pre-ovulatory follicle growth is suppressed during pregnancy, c-kit mRNA expression was limited to large luteal cells of the CL. The expression of c-kit mRNA in endothelial tissue (Miyamoto et al. 1994) and luteal cells (Gentry et al. 1998) is also supported by other studies. Oocyte expression of c-kit mRNA in mice, rats, humans and marsupials has been well documented (Manova et al. 1990; Ismail et al. 1997; Tanikawa et al. 1998; Eckery et al. 2002). Unfortunately, no oocytes were present in the tissue sections examined from mature (pregnant or non-pregnant) animals. However, c-kit mRNA was detected in oocytes from preantral and small antral follicles in prepubertal animals.

The current findings demonstrate the patterns of expression of c-kit and SCF mRNA in the different ovarian cell compartments and indicate that the presence of important cellular interactions may mediate a range of functions both in the adult and in the prepubertal animal. There also appears to be species variations in expression between mono- and poly-ovulatory animals, particularly with regard to SCF expression. In small poly-ovulatory species such as the mouse, SCF is expressed during early stages of follicular growth (Joyce et al. 1999). In large mono-ovulatory species such as the cow, large pre-ovulatory follicles express SCF (Parrott & Skinner 1997). This study has demonstrated for the first time in a large poly-ovulatory species that SCF mRNA is expressed in antral follicles, but not large preantral follicles. The physiological implications of SCF and c-kit mRNA expression at all the stages of follicle and CL development studied suggest that the growth factor–ligand complex is biologically active throughout follicle growth and development and the expression patterns of SCF mRNA throughout endothelial tissue support its role in angiogenesis. Localization of SCF and c-kit mRNA in the prepubertal animal suggests that both the receptor and the growth factor are responsible for ovarian cell differentiation and oocyte development. Expression patterns in the mature animal suggest SCF and c-kit are responsible for the maintenance of progesterone production and/or secretion from the corpus luteum of pregnancy in the sow and hence help to maintain pregnancy in the pig.

In conclusion, the role of SCF–c-kit interaction depends upon the stage of development. The continuous expression of SCF mRNA in endothelial tissue suggests that SCF may play a pivotal role in angiogenesis and hence steroidogenesis. Future work should be aimed at determining the changing levels of both transcripts at defined stages of development such as during different stages of pregnancy and throughout the oestrous cycle. This would delineate the continuous role of SCF and c-kit in germ and somatic cell function during follicle growth and development.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank John Corbett for tissue collection and Charis Hogg for her assistance and advice on probe preparation.

References

- Bagavandoss P, Midgley AR, Wicha M. Developmental changes in the ovarian follicular basal lamina detected by immunofluorescence and electron microscopy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1983;31:633–640. doi: 10.1177/31.5.6341456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedell MA, Brannan CI, Evans EP, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Donovan PJ. DNA rearrangements located over 100 kb 5′ of the steel (Sl)-coding region in steel –panda and steel-contrasted mice deregulate Sl expression and cause female sterility by disrupting ovarian follicle development. Genes Dev. 1995;9:455–470. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besmer P. The kit ligand encoded at the murine steel locus: a pleiotropic growth and differentiation factor. Current Opinion Cell Biol. 1991;3:939–946. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brankin V, Mitchell MRP, Webb R, Hunter MG. Paracrine effects of oocyte secreted factors and stem cell factor on porcine granulosa and theca cells in vitro. Reprod Biol. Endocrinol. 2003;1:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-55. http://www.RBEj.com/content/1/1/55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DE, Tisdall DJ, Fidler AE, McNatty KP. Localisation of mRNA encoding c-kit during the initiation of folliculogenesis in ovine fetal ovaries. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1996;106:329–335. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1060329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckery DC, Lawrence SB, Juengel JL, Greenwood P, McNatty KP, Fidler AE. Gene expression of the tyrosine kinase receptor c-kit during ovarian development in the bushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) Biol. Reprod. 2002;66:346–353. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G, Dobias M, King GJ, Armstrong DT. Estrogen, androgen, and progesterone biosynthesis by theca and granulosa of preovulatory follicles in the pig. Biol. Reprod. 1981;25:673–682. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod25.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk B. Site of production of oestrogen in rat ovary as studied in micro-transplants. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1959;47:1–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1960.tb01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry PC, Smith GW, Anthony RV, Zhang Z, Long DK, Smith MF. Characterisation of ovine stem cell factor messenger ribonucleic acid and protein in the corpus luteum oestrogen in rat ovary as phase. Biol. Reprod. 1996;54:970–979. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.5.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry PC, Smith GW, Leighr DR, Bao B, Smith M. Ontogeny of stem cell factor receptor (c-kit) messenger ribonucleic acid in the ovine corpus luteum. Biol. Reprod. 1998;59:983–990. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.4.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie K, Takakura K, Taii S, et al. The expression of c-kit protein during oogenesis and early embryonic development. Biol. Reprod. 1991;45:547–552. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod45.4.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CTF, Weitsman SR, Dykes BN, Magoffin DA. Stem cell factor and insulin-like growth factor-I stimulate luteinizing hormone independent differentiation of rat ovarian theca cells. Biol. Reprod. 2001;64:451–456. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail RS, Dube M, Vanderhyden BC. Hormonally regulated expression and alternative splicing of kit ligand may regulate kit-induced inhibition of meiosis in rat oocytes. Dev. Biol. 1997;184:333–342. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail RS, Cada M, Vanderhyden BC. Transforming growth factor-β regulates kit ligand expression in rat ovarian surface epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:4734–4741. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce IM, Pendola FL, Wiggleswoth K, Eppig JJ. Oocyte regulation of kit ligand expression in mouse ovarian follicles. Dev. Biol. 1999;214:342–353. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junquiera LC, Carneiro J, Kelly RO. Basic Histology. Norwalk: Appleton & Lange; 1989. pp. 443–444. [Google Scholar]

- Keshet E, Lyman SD, Williams DE, et al. Embryonic RNA expression patterns of the c-kit receptor and its cognate ligand suggest multiple functional roles in mouse development. EMBO J. 1991;10:2425–2435. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoffin DA, Huang CTF, Weitsman SR. Insulin-like growth factor I and stem cell factor are necessary for differentiation of pre-thecal cells into mature thecal cells. Biol. Reprod. 1999;60(Suppl. 1):269–270. [Google Scholar]

- Manova K, Nocka K, Besmer P, Bachvarova RF. Gonadal expression of c-kit encoded at the W locus of the mouse. Development. 1990;110:1057–1069. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manova K, Huang EJ, Angeles M, et al. The expression pattern of the c-kit ligand in gonads of mice supports a role for the c-kit receptor in oocyte growth and in proliferation of spermatogonia. Dev. Biol. 1993;157:85–99. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T, Sasaguri Y, Sugama K, Azakami S, Morimatsu M. Expression of the c-kit mRNA in human aortic endothelial cells. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1994;34:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motro B, Bernstein A. Dynamic changes in ovarian c-kit and steel expression during the estrous reproductive cycle. Dev. Dynamics. 1993;197:69–79. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001970107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott JA, Skinner MK. Direct actions of kit-ligand on theca cell growth and differentiation during follicle development. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3819–3827. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott JA, Skinner MK. Kit ligand/Stem cell factor induces primordial follicle development and initiates folliculogenesis. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4262–4271. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott JA, Kim G, Skinner MK. Expression and action of kit ligand/stem cell factor in normal human and bovine ovarian surface epithelium and ovarian cancer. Biol. Reprod. 2000;62:1600–1609. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud K, Cortvrindt R, Smitz J, Driancourt M. Effects of kit ligand and anti-kit antibody on growth of cultured mouse preantral follicles. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2000;56:483–494. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(200008)56:4<483::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanikawa M, Haraha T, Mitsunari M, Onohara Y, Iwabe T, Terakawa N. Expression of c-kit messenger ribonucleic acid in human oocyte and presence of soluble c-kit in follicular fluid. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998;83:1239–1242. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.4.4746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall DJ, Quirke LD, Smith P, McNatty KP. Expression of the ovine stem cell factor gene during folliculogenesis in late fetal and adult ovaries. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;18:127–135. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0180127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall DJ, Fidler AE, Smith P, et al. Stem cell factor and c-kit gene expression and protein localisation in the sheep ovary during fetal development. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1999;116:277–291. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1160277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang BK, Ainsworth L, Downy BR, Marcus GJ. Differential production of steroids by dispersed granulosa and theca interna cells from developing preovulatory follicles of pigs. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1985;74:459–471. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0740459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Takakura N, Kataoka H, Kunisada T, Okamura H, Nishikawa S. Step-wise requirement of c-kit tyrosine kinase in mouse ovarian follicle development. Dev. Biol. 1997;184:122–137. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Redmer DA, Reynolds LP. Vascular development and heparin-binding growth factors in the bovine corpus luteum at several stages of the estrous cycle. Biol. Reprod. 1993;49:1177–1189. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.6.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]