Abstract

The porcine eye serves as a model to study various functions of the aqueous outflow system. To compare these data with the primate eye, a detailed investigation of the distribution of contractile properties and of the innervation of the outflow region was conducted in the porcine eye. In all quadrants of the anterior eye segment, elastic fibres connected the ciliary muscle (CM) with the well-developed scleral spur (ScS) and also partly with the corneoscleral trabecular meshwork (TM) and the loops of the collecting outflow channels. Immunohistochemistry with antibodies against smooth muscle α-actin revealed intense staining of the CM and some myofibroblasts in the ScS and outer TM. In addition to a few cholinergic and aminergic nerve fibres in the outflow region, numerous substance P- and calcitonin-gene related peptide-positive nerve fibres and nerve endings were found near the outflow loops of the porcine TM. Although the porcine CM serves rather as a tensor choroideae muscle than as a muscle for accommodation, the innervation and morphology of the collecting outflow channel loops and of the expanded TM between the ScS and the cornea showed close similarities to the primate eye.

Keywords: calcitonin-gene related peptide, ciliary body, electron microscopy, substance P, trabecular meshwork

Introduction

Owing to its similar size compared with human eyes, and also its availability, the porcine eye is a well-established model for studying functional aspects of the aqueous outflow system and the influence of different factors on outflow facility (Karnezis et al. 1989; Tripathi et al. 1991; 1993; 1994; 1997; 2004; Matsuo et al. 1996; Epstein et al. 1997; Li et al. 2000; Rao et al. 2001). However, several morphological differences have been described, especially in the outflow region of the porcine compared with the primate eye. These include regional differences of the scleral spur (ScS) in the nasal and temporal quadrants (Prince et al. 1960), a deep ciliary cleft crossed by stout pectinate ligaments and delicate uveal cords (McMenamin & Steptoe, 1991), and single loops instead of a complete Schlemm's canal draining the aqueous humor to the collector channels (Tripathi & Tripathi, 1972).

Recently, we have been able to show that specific nitrergic neurons within the ciliary nerves project to the outflow region, both in human and in porcine eyes (May et al. 2002). In addition, morphological studies have revealed a complex innervation of the trabecular meshwork (TM) and ScS region in human and primate eyes (Tamm et al. 1994; 1995; Selbach et al. 2000): both regions contain substance P (SP)- and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-immunoreactive (IR) nerve fibres of presumably afferent trigeminal origin, as well as cholinergic and aminergic efferent nerve endings that might supply the contractile cells present in the ScS and in the TM of human and primate eyes (Selbach et al. 2000). Various pharmacological studies performed in human and bovine cell cultures of TM cells and in perfused anterior eye segments indicate that contraction of TM cells reduces relaxation and increases aqueous humor outflow facility (Wiederholt et al. 1994; 1995).

The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether similar contractile cells also exist in the outflow region of the porcine eye, and how this region is supplied by other than the already described nitrergic nerve fibres (May et al. 2002).

Materials and methods

The eyes of 53 domestic pigs were obtained from the local abattoir within 30 min after death; they were trimmed for extraocular muscles and bisected equatorially. The temporal quadrant was defined by the entry of the long ciliary nerves and the position of the optic nerve, and marked by an incision.

Histology

To demonstrate collagen and elastic fibres in the porcine ciliary muscle and outflow region, eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 h and then rinsed several times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2–7.4). The anterior segments were dissected into four quadrants and each quadrant subdivided into two segments. All tissue samples were embedded in paraffin, and sagittal and tangential 5-µm-thick sections were cut through the ciliary body and trabecular meshwork region. The sections were either stained with a trichrom-stain (Crossmont) to differentiate between cytoplasmic (red) and extracellular material (green) structures, or incubated in a Resorcin-Fuchsine stain (Weigert) to demonstrate elastic fibres. The stained sections were mounted with Entellan and viewed with a Leica microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Fixation of anterior segments was performed for 4–12 h at 4 °C, the solution containing 4% PFA and 0.01% picric acid. After rinsing in PBS, the dissected temporal and nasal quadrants were cryoprotected in 20% saccharose for 12–24 h at 4 °C. Sagittal and tangential 12–20-µm-thick frozen serial sections were mounted on poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides. Incubation with the primary antibodies (listed in Table 1) was performed in a moist chamber overnight at room temperature, the antibodies diluted in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% Triton X. The sections were then rinsed three times for 10 min each with PBS and incubated with an appropriate Cy3-marked secondary antibody (goat-antirabbit Cy3, diluted 1 : 2000; DAKO, Hamburg, Germany) for at least 1 h. After rinsing with PBS again the sections were mounted with glycerine jelly.

Table 1.

List of primary antibodies used in this study

| Antibody specificy | Provider | Host | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurofilament (NF) | Biotrend | rabbit | 1 : 500 |

| Vesicular-acetylcholin transporter (VAChT) | Phoenix | rabbit | 1 : 2000 |

| Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) | Biotrend | rabbit | 1 : 400 |

| Neuropeptide Y (NPY) | Phoenix | rabbit | 1 : 400 |

| Vasointestinal peptide (VIP) | Biotrend | rabbit | 1 : 400 |

| Substance P (SP) | Biotrend | rabbit | 1 : 500 |

| Calcitonine gene-related peptide (CGRP) | Biotrend | rabbit | 1 : 500 |

| Vesicular monoaminergic transporter (VMAT-2) | Phoenix | rabbit | 1 : 1500 |

In some sections, double staining was performed using a Cy2-labelled antibody against smooth muscle α-actin (diluted 1 : 150; Sigma, Cologne, Germany) as a second primary antibody. After incubation for 1 h, the sections were rinsed and mounted as above. Control sections were made for each staining, replacing the primary antibody with the pure dilution solution.

The sections were evaluated with a Leica fluorescence microscope.

Electron microscopy

The anterior segments of six eyes were immediately dissected into four quadrants and small sections immersion-fixed in Itos solution, containing 2% glutaraldehyde, 4% PFA and 0.01% picrinic acid in cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). The specimens were rinsed in cacodylate buffer, post-fixed in osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ascending series of alcohol and embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections through the ciliary muscle and trabecular meshwork region were stained with uranyl acetate and leaded citrate and examined with an electron microscope (EM 109; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Results

Ciliary muscle (CM)

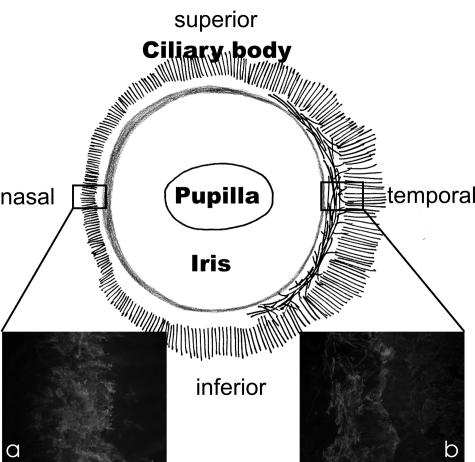

In a series of sagittal sections over the entire circumference of the porcine anterior eye segment, the CM was constantly present but showed clear regional differences; in the nasal quadrant, only sparse longitudinally orientated CM fibres were seen in the posterior part of the ciliary body, and these entered the ScS and did not reach the TM region (Fig. 1a). In the temporal quadrant, the CM was more elaborated and an inner, rudimentary circular portion could be differentiated from an outer longitudinal portion (Fig. 1b). Most of the longitudinal muscle fibres contacted the sclera and ScS, but single fibres also reached the posterior part of the TM.

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the porcine anterior eye segment viewed externally to demonstrate the orientation and size of the ciliary muscle (black lines). Note the different appearance of the ciliary muscle (stained with smooth muscle α-actin) with only longitudinally orientated muscle fibres in the nasal (a), and longitudinally and circumferentially orientated muscle fibres in the temporal (b) quadrant.

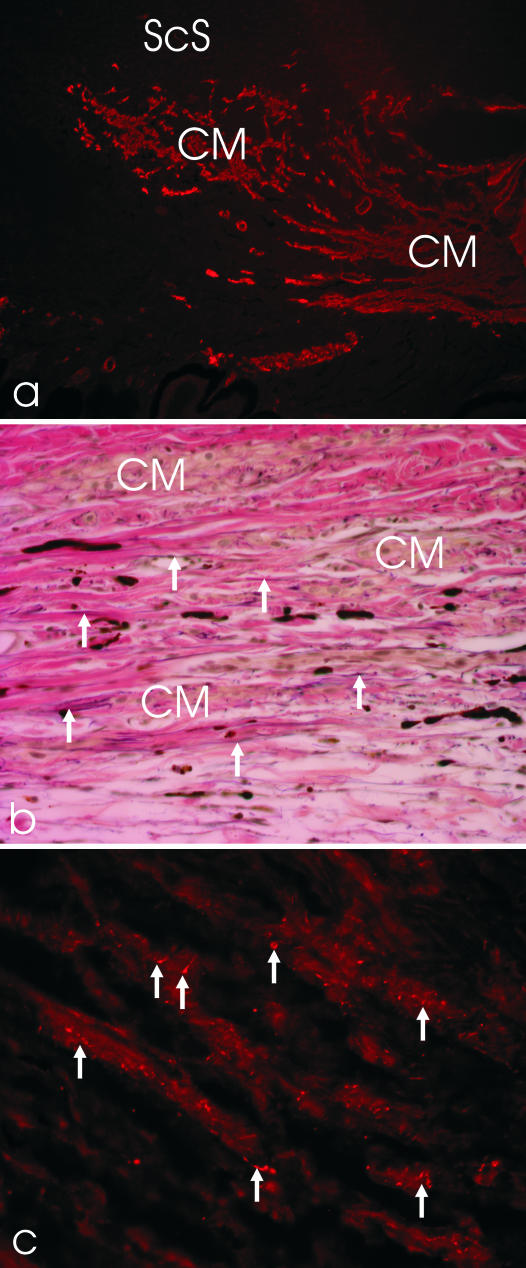

Immunohistochemical staining showed a bright staining of smooth muscle α-actin in the CM (Fig. 2a). At the ultrastructural level, the CM cells showed no disciform or parallel arrangement of the myofilaments but dense bands at the cell surface membrane, typically seen in smooth muscle cells of the vessel walls and gut. The single muscle cells were surrounded by a complete basement membrane connecting the cells to the elastic network located between the CM. Serial sagittal and transverse sections through the CM and TM region showed a fine, substantial network of elastic fibrils extending from the choroid through the ciliary muscle to the outflow region. Within the CM, the elastic fibres were orientated mainly longitudinally (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

(a) A temporal porcine anterior eye segment section stained with antibodies against smooth muscle α-actin (×100). ScS, scleral spur; CM, ciliary muscle, longitudinal and circumferential portion. (b) Elastica-staining of the CM region in the temporal quadrant of a porcine eye. Note the parallel arrangement of the elastic fibres (arrows), arranged in the same direction as the CM cells (×200). (c) The CM is supplied by numerous cholinergic nerve fibres and boutons (arrows; ×400).

Nerve fibres and endings, stained with an antibody against the vesicular acetylcholine transporter and thus presumably cholinergic in nature, were frequently located next to the CM cells (Fig. 2c). Aminergic nerve fibres, demonstrated with both antibodies against TH and VMAT-2, were only sparsely present and restricted to vascular walls. The other neurotransmitters tested (VIP, NPY, SP, CGRP) revealed no positive nerve fibres or endings within the CM (Table 2).

Table 2.

Semiquantitative evaluation of the distribution of various neuronal markers within the anterior segment of the porcine eye

| Ciliary body | Ciliary muscle | Scleral spur | Trabecular meshwork | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| VAChT | (+) | ++ | 0 | (+) |

| TH | v | v | 0 | v |

| VMAT-2 | v | v | 0 | v |

| NPY | (+) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VIP | (+) | 0 | 0 | (+) |

| SP | + | (+) | + | ++ |

| CGRP | (+) | (+) | + | ++ |

0 = no nerve fibres, (+) = single nerve fibres, + = some nerve fibres, ++ = numerous nerve fibres present; V = only innervation of the vessels.

Scleral spur (ScS)

Similar to and in parallel with the CM, the ScS showed clear regional differences in its occurrence: in the nasal region, a small but notable spur was present. In contrast, the ScS in the temporal quadrant was distinct (Fig. 2a).

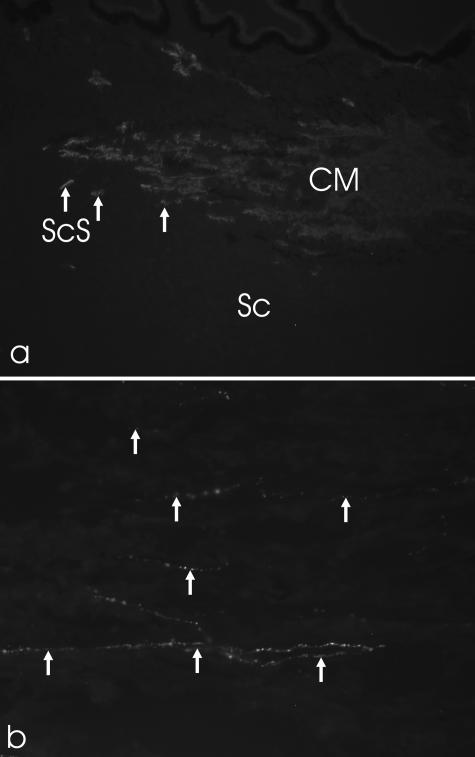

Within the ScS, smooth muscle α-actin-positive cells could be detected in all quadrants of the porcine eye (Fig. 3a). At the ultrastructural level, the cells were incompletely surrounded by basement membranes similar to myofibroblasts.

Fig. 3.

(a) Smooth muscle α-actin staining of the scleral spur (ScS) region in the nasal quadrant of a porcine eye (×100). Note the star-shaped cells (arrows). (b) Staining with antibodies against substance P revealed numerous nerve fibre boutons (arrows) in the ScS region (tangential section; ×400). Sc, sclera.

Only a sparse innervation was found within the circumference of the ScS: SP- and CGRP-positive nerve fibres and bouton-like endings were present (Fig. 3b). Aminergic nerve fibres, demonstrated with both antibodies against TH and VMAT-2, were occasionally present. No staining was observed with antibodies against VAChT, VIP and NPY.

Trabecular meshwork (TM)/outflow region

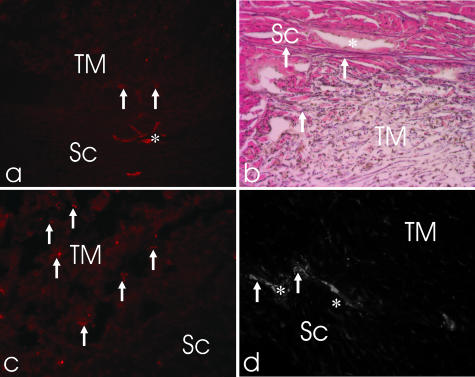

Only sparse staining for smooth muscle α-actin was noted in the porcine TM. The single positive cells were mainly concentrated in close vicinity to the outflow loops and towards the iris root (Fig. 4a). This staining, similar to the myofibroblast-like cells in the ScS, showed no regional differences.

Fig. 4.

(a) Smooth muscle α-actin staining of the trabecular meshwork (TM) region in the nasal quadrant of a porcine eye shows only single cells in the TM (arrows; ×200). (b) Elastica-staining shows the fine elastic fibrils (arrows) next to the outflow channels (asterisk) and in the TM (×400). (c) Numerous substance P-positive nerve fibres (arrows) are located in the TM (×200). (d) In contrast, only single cholinergic nerve fibres (arrows) were located in the outer TM next to the outflow channels (asterisk; ×200). Sc, sclera.

The elastic fibres followed the straight orientation of the CM fibres to the loops in the inner sclera at the level of the TM. Near the outflow loops they changed their orientation and formed a complex three-dimensional network (Fig. 4b).

General staining of nerve fibres with antibodies against neurofilament revealed a comparable dense distribution of nerve fibres in the outflow region of all four different quadrants. There were numerous SP- and CGRP-positive nerve fibres and bouton-like endings throughout the TM. Some of these positive nerve fibres crossed the region supplying the cornea and the iris. The other nerve fibres formed an elaborated network within the TM (Fig. 4c). The density of SP/CGRP-positive nerve fibres supplying the outflow region was high in the corneoscleral portion of the TM, highest around the loops. Ultrastructural investigations of this region revealed vesicle-filled boutons in direct contact with the endothelial cells of the loop formations.

In contrast, only single cholinergic and aminergic nerve fibres were located in the inner reticular TM towards the iris root (Fig. 4d). There, they mainly supplied the arterioles. VIP-IR nerve fibres were only occasionally seen in the inner portion of the reticular TM towards the iris root. No VIP-IR nerve fibres were detected next to the loops and collector channels. NPY-IR nerve fibres were absent in the TM.

Discussion

Although the gross histological appearance of the porcine anterior eye segment confirmed the description by McMenamin & Steptoe (1991) and showed characteristic differences from the primate eye, detailed analysis of serial tangential and sagittal sections revealed additional findings explaining the functional aspects in both species.

The porcine CM is substantially smaller than the primate CM and shows prominent circumferential differences. In addition to the longitudinal portion of the CM, which is always present in the porcine eye, the circular portion, forming the major part for accommodation (Rohen, 1952; Flügel et al. 1990; Tamm & Lütjen-Drecoll, 1996), is only adumbrated in the temporal quadrant. Ultrastructurally, the muscle cells show characteristics of smooth muscle cells and do not show the elaborated morphology described for the primate CM cells (Flügel et al. 1990; Ebersberger et al. 1993). In addition, the porcine CM does not show tendon-like formations towards the TM as seen in the primate eye (Rohen, 1962; Lütjen-Drecoll et al., 1981; Hamanaka, 1989; Lütjen-Drecoll et al. 1998; Lütjen-Drecoll 1999; Gabelt et al. 2003). Instead, the CM is surrounded by an elaborate elastic net connected anteriorly with the TM and posteriorly with the elastic network of the choroid. It is tempting to speculate that the function of the CM in this specific position is as a ‘tensor choroideae’, regulating or modulating the elastic forces in the choroid, rather than as an accommodative muscle with influences to the TM. Because there is no direct force of the CM affecting the TM in the porcine eye, the intense ScS seems to be sufficient to keep the outflow tissue functionally open. Presumably no additional active regulation in the TM is necessary. This is different to the bovine eye, where virtually no ScS is present. There, the TM has to play an active role in keeping the outflow pathways open. Indeed, numerous contractile cells are described to be present in the bovine TM (Grierson et al. 1986; Flügel et al. 1991; Lepple-Wienhues et al. 1991; Wiederholt et al. 1994; 1995).

Comparing the innervation of the porcine and human outflow region, the pattern and localization of the different neurotransmitters investigated was almost identical. It is tempting to speculate that the SP- and CGRP-positive nerve endings in the trabecular meshwork have a similar function as speculated for the human eye. In the latter they might be involved in sensory registration of the trabecular meshwork tension and might initiate a neuronal regulation of the outflow resistance via the nitrergic and cholinergic innervation. In vitro studies have shown that bovine and primate trabecular meshwork cells contract after incubation with acetylcholine (Wiederholt et al. 1995) whereas nitric oxide relaxes the cells (Wiederholt et al. 1994).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by DFG: SFB 539, BI, 1.

References

- Ebersberger A, Flügel C, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Ultrastructural and enzyme histochemical studies of regional structural differences within the ciliary muscle in various species. Klin. Monatsbl. Augenheilkd. 1993;203:53–58. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1045648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DL, Roberts BC, Skinner LL. Nonsulfhydryl-reactive phenoxyacetic acids increase aqueous humor outflow facility. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997;38:1526–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügel C, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Barany E. Über strukturelle Unterschiede im Aufbau des Ziliarmuskels des Primatenauges. Fortschr. Ophthalmol. 1990;87:384–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügel C, Tamm E, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Different cell populations in bovine trabecular meshwork: an ultrastructural and immunocytochemical study. Exp. Eye Res. 1991;52:681–690. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90020-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabelt BT, Gottanka J, Lutjen-Drecoll E, Kaufman PL. Aqueous humor dynamics and trabecular meshwork and anterior ciliary muscle morphologic changes with age in rhesus monkeys. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:2118–2125. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson I, Millar L, De Yong J, et al. Investigations of cytoskeletal elements in cultured bovine meshwork cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1986;27:1318–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka T. Scleral spur and ciliary muscle in man and monkey. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 1989;33:221–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnezis TA, Tripathi BJ, Dawson G, Murphy MB, Tripathi RC. Effects of dopamine receptor activation on the level of cyclic AMP in the trabecular meshwork. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989;30:1090–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepple-Wienhues A, Stahl F, Wiederholt M. Differential smooth muscle-like contractile properties of trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle. Exp. Eye Res. 1991;53:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC. Modulation of pre-mRNA splicing and protein production of fibronectin by TGF-beta2 in porcine trabecular cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:3437–3443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütjen-Drecoll E, Futa R, Rohen JW. Ultrahistochemical studies on tangential sections of the trabecular meshwork in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1981;21:563–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütjen-Drecoll E, Wiendl H, Kaufman PL. Acute and chronic structural effects of pilocarpine on monkey outflow tissues. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1998;96:171–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütjen-Drecoll E. Functional morphology of the trabecular meshwork in primate eyes. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1999;18:91–119. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo T, Uchida H, Matsuo N. Bovine and porcine trabecular cells produce prostaglandin F2 alpha in response to cyclic mechanical stretching. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 1996;40:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May CA, Fuchs AV, Scheib M, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Characterization of nitrergic neurons in the porcine and human ciliary nerves. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin PG, Steptoe J. Normal anatomy of the aqueous humor outflow system in the domestic pig eye. J. Anat. 1991;178:65–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince J, Diesem C, Eglitis I, Ruskell G. Anatomy and Histology of the Eye and Orbit in Domestic Animals. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publishers; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rao PV, Deng PF, Kumar J, Epstein DL. Modulation of aqueous humor outflow facility by the Rho kinase-specific inhibitor Y-27632. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42:1029–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohen J. Der Ziliarkörper als funktionelles System. Gegenb. Morph. Jahrb. 1952;92:415–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rohen JW. Sehorgan. In: Hofer H, Schultz AH, Starck D, editors. Handbook of Primatology. New York: Karger Verlag; 1962. pp. 1–197. [Google Scholar]

- Selbach JM, Gottanka J, Wittmann M, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Efferent and afferent innervation of primate trabecular meshwork and scleral spur. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:2184–2191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Flugel C, Stefani FH, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Nerve endings with structural characteristics of mechanoreceptors in the human scleral spur. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994;35:1157–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Koch TA, Mayer B, Stefani FH, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Innervation of myofibroblast-like scleral spur cells in human monkey eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1995;36:1633–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Ciliary Body. Microsc. Res. Techn. 1996;33:390–439. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19960401)33:5<390::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC, Yang C, Millard CB, Dixit VM. Synthesis of a thrombospondin-like cytoadhesion molecule by cells of the trabecular meshwork. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1991;32:181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi BJ, Li T, Li J, Tran L, Tripathi RC. Age-related changes in trabecular cells in vitro. Exp. Eye Res. 1997;64:57–66. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC, Chen J, Gotsis S, Li J. Trabecular cell expression of fibronectin and MMP-3 is modulated by aqueous humor growth factors. Exp. Eye Res. 2004;78:653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi RC, Tripathi BJ. The mechanism of aqueous outflow in lower mammals. Exp. Eye Res. 1972;14:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(72)90146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi RC, Li J, Borisuth NS, Tripathi BJ. Trabecular cells of the eye express messenger RNA for transforming growth factor-beta 1 and secrete this cytokine. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:2562–2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi RC, Chan WF, Li J, Tripathi BJ. Trabecular cells express the TGF-beta 2 gene and secrete the cytokine. Exp. Eye Res. 1994;58:523–528. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt M, Sturm A, Lepple-Wienhues A. Relaxation of trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle by release of nitric oxide. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994;35:2515–2520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt M, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Bielka S, Schwig FA, Lepple-Wienhues A. Regulation of outflow rate and resistance in the perfused anterior segment of the bovine eye. Exp. Eye Res. 1995;61:223–234. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]