Abstract

Nitrergic nerve fibres of intrinsic and extrinsic origin constitute an important component of the autonomic innervation in the human eye. The intrinsic source of nitrergic nerves are the ganglion cells in choroid and ciliary muscle. In order to obtain more information on the origin of extrinsic nitrergic nerves in the human eye, we obtained superior cervical, ciliary, pterygopalatine and trigeminal ganglia from six human donors, and stained them for neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-diaphorase (NADPH-D). In the superior cervical ganglia, nNOS/NADPH-D-positive varicose axons were observed whereas perikarya were consistently negative. Fewer than 1% of perikarya in the ciliary ganglia were labelled for nNOS/NADPH-D. The diameter of nNOS/NADPH-D-positive ciliary perikarya was between 8 and 10 µm, which was markedly smaller than the diameter of the vast majority of negative perikarya in the ciliary ganglion. More than 70% of perikarya in the pterygopalatine ganglia were intensely labelled for both nNOS and NADPH-D. In trigeminal ganglia, 18% of perikarya were nNOS/NADPH-D-positive. The average diameter of trigeminal nNOS/NADPH-D perikarya was between 25 and 45 µm. Pterygopalatine and trigeminal ganglia are the most likely sources for extrinsic nerve fibres to the human eye.

Keywords: ciliary ganglion, NADPH-diaphorase, pterygopalatine ganglion, superior cervical ganglion, trigeminal ganglion

Introduction

There is a considerable amount of evidence that nitrergic axons play an important role in the autonomic innervation of the human eye (Tamm & Lütjen-Drecoll, 2000). Nitrergic nerves are characterized by the presence of nitric oxide and the catalysing enzyme neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), and stain for reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-diaphorase (NADPH-D). Nitric oxide released from nitrergic terminals appears to play a role in modulating the blood supply to various intraocular tissues, and to take part in the accommodation of the optical system and the circulation of the aqueous humor. A predominant source of nitrergic axons in the human eye are the intrinsic ganglion cells that are localized in the choroid (Bergua et al. 1993; Flügel et al. 1994b) and the ciliary muscle (Tamm et al. 1995a). Such ganglion cells appear to be characteristic of human eyes and are less frequent or absent in mammals that lack a fovea centralis (Flügel-Koch et al. 1994b; Tamm & Lütjen-Drecoll, 1996). Both ciliary and choroidal ganglion cells give rise to processes that contact other intrinsic ganglion cells or smooth muscle cells in choroid and ciliary body (Tamm et al. 1995a; Schrödl et al. 2003; May et al. 2004). A subpopulation of intrinsic ganglion cells has been observed in short ciliary nerves (May et al. 2002). In addition to the intrinsic nitrergic innervation, the contribution of extrinsic autonomic nerve fibres to the nitrergic innervation of the human eye appears more than likely, as such fibres have been observed in the wall of short posterior ciliary arteries before and shortly after they penetrate the sclera (Tamm & Lütjen-Drecoll, 2000). In general, such fibres may originate in superior cervical, ciliary or pterygopalatine ganglia, all of which contribute to the autonomic innervation of the human eye, or in the trigeminal ganglion, which gives rise to afferent neurons releasing neuroactive molecules from their peripheral terminals. Nitrergic nerves are commonly identified by immunoreactivity for nNOS and/or staining for NADPH-D. In humans, the pterygopalatine ganglion contains numerous NADPH-D-reactive perikarya and appears to be the most likely source for ocular extrinsic nitrergic nerves (Hanazawa et al. 1997; Uddman et al. 1999). In contrast, very few or no nNOS-positive cells have been found in human ciliary (Demer et al. 1995) and superior cervical ganglia (Tajti et al. 1999a). In human trigeminal ganglia, a minority of cells were positive for nNOS (Tajti et al. 1999b). A critical problem in any studies using human material is the fact that data from different laboratories are difficult to compare as nNOS and NADPH-D reactivity decreases substantially with prolonged post mortem times, and lack of staining does not necessarily prove lack of nitrergic activity in vivo. The goal of the present study was therefore to make a direct comparison of the amount of nNOS/NADPH-D-reactive ganglion cells in superior cervical, ciliary, pterygopalatine and trigeminal ganglia from the same individual human donors, and to add to our knowledge of likely sources of extrinsic nitrergic nerves to the human eye.

Materials and methods

Superior cervical, ciliary, pterygopalatine and trigeminal ganglia from six human donors (age range 43–93 years) were removed 3–7 h after death and fixed overnight in Zamboni's fixative (Stefanini et al. 1967). After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 30% sucrose for 24 h, serial 20-µm cryostat sections were cut, mounted on slides covered with 0.1% poly-l-lysine and pre-incubated for 30 min in Blotto's dry milk solution (Duhamel & Johnson, 1985). After pre-incubation, the sections were incubated overnight at room temperature with rabbit antibodies against nNOS (1: 500) and washed again in PBS. The antibodies had been generated against NOS purified from porcine cerebellum and successfully tested for Western blot analysis (Klatt et al. 1992) and immunohistochemistry (Tamm et al. 1995a,b; Flügel-Koch et al. 1996). After 1 h of incubation with biotinylated secondary antibodies (Amersham Buchler, Braunschweig, Germany), the sections were covered with streptavidin-FITC (Dakopatts, Hamburg, Germany), washed again in PBS, mounted in Entellan (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) containing 1.4 diazabicyclo[2,2,2] octan (DABCO, Merck), and viewed with a Leitz Aristoplan microscope (Ernst Leitz GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Kodak T-max 400 film was used for photography. For NADPH-D histochemistry, sections were incubated in a moist chamber at 37 °C using the following medium: β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate/tetrasodium salt (reduced NADPH-D; Biomol, Hamburg, Germany), 1 mg mL−1; nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany), 0.1 mg mL−1; 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1 m PBS, pH 7.4. After incubation for 1 h, the sections were rinsed in PBS and mounted in Kaiser's glycerine gelatin (Merck). To measure the number of positively stained perikarya, serial sections through ciliary ganglia were labelled, and all cells were evaluated. For pterygopalatine, superior cervical and trigeminal ganglia, 100 perikarya per each ganglion were evaluated. For quantitative evaluation of the size of the trigeminal perikarya, measurements were made at a magnification of ×400 by tracing the diameters on a digitizing board. All ganglion cells that were cut through the centre of the perikaryon (with visible nucleus) on a section parallel to the surface of the ganglion containing ophthalmic, maxillar and mandibular portions were considered. Seven trigeminal ganglia from six donors were quantitatively evaluated.

Results

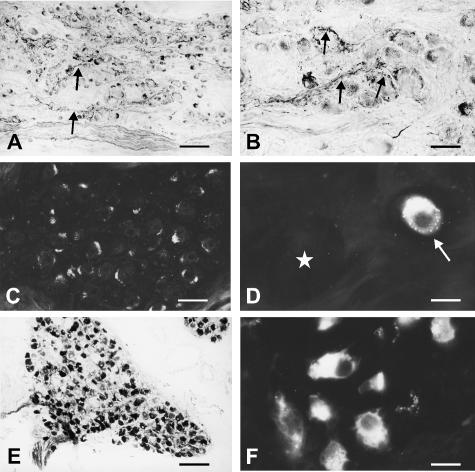

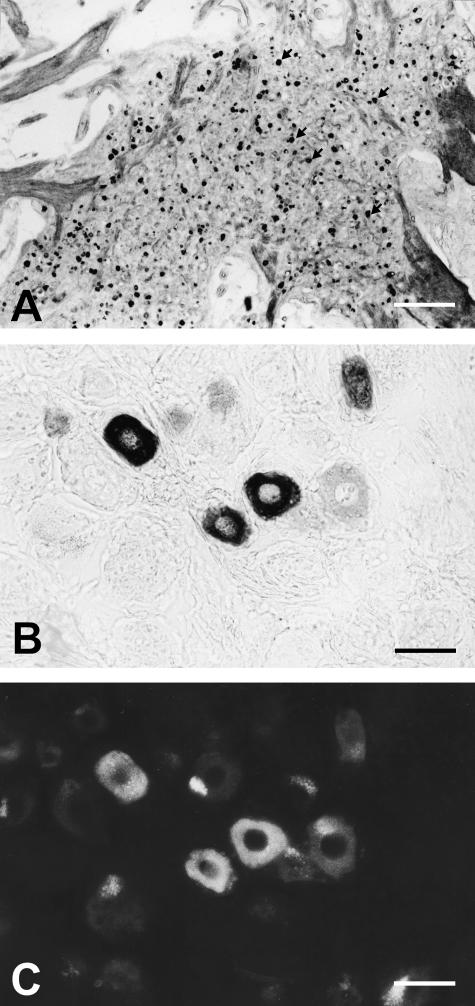

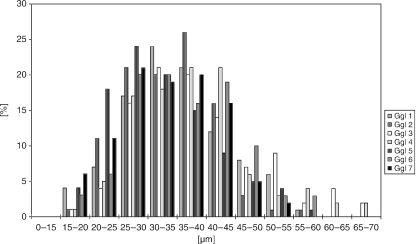

In superior cervical ganglia from all of the human donors, nNOS- and NADPH-D-positive varicose axons were observed that surrounded ganglion cell perikarya and that were in intimate contact with some of the perikarya (Fig. 1A,B). Superior cervical perikarya were consistently negative for nNOS/NADPH-D (Fig. 1A,B). A similar absence of nNOS/NADPH-D labelling was found in ciliary ganglia from three of the human donors (Fig. 1C), while some solitary cells that were intensely labelled for both nNOS and NADPH-D were observed in ciliary ganglia from the three other donors (Fig. 1D). In total, fewer than 1% of perikarya in those individual ciliary ganglia were positive for nNOS/NADPH-D (Table 1). The diameter of nNOS/NADPH-D-positive ciliary perikarya was between 8 and 10 µm and markedly smaller than that of the vast majority of negative perikarya in the ciliary ganglion, which had diameters of more than 20 µm. In contrast to ciliary and superior cervical ganglia, more than 70% of perikarya in the pterygopalatine ganglia of all of the donors were intensely labelled for both nNOS and NADPH-D (Fig. 1E,F, Table 1). The size of nNOS/NADPH-D-positive pterygopalatine perikarya was similar to those few cells that were nNOS/NADPH-D-reactive in ciliary ganglia. In trigeminal ganglia, 18% of perikarya were nNOS/NADPH-D positive (Fig. 2a,Table 1). These cells were equally distributed throughout the mandibular, maxillar and ophthalmic portions of the ganglion. No obvious differences between right and left ganglia were observed in the trigeminal ganglia from the one donor in which both ganglia were investigated. The average diameter of trigeminal nNOS/NADPH-D perikarya was between 25 and 45 µm (Fig. 3) Staining intensities for NADPH-D varied between individual trigeminal ganglion cells. Some of the cells were intensely labelled (5.6 ± 1.8%), whereas others showed only moderate staining (12.7 ± 3.1%) (Fig. 2B). Double staining with both NADPH-D and antibodies against nNOS showed a distinct correlation in labelling intensity (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

NADPH-D (A, B, E) and nNOS (C, D, F) staining in human superior cervical (A, B), ciliary (C, D) and pterygopalatine (E, F) ganglia. (A) In superior cervical ganglia, NADPH-D-positive varicose axons (arrows) are frequently observed between ganglion cell perikarya. (B) NADPH-D-positive varicose axons (arrows) are in intimate contact with superior cervical perikarya, which are negative for NADPH-D. (C) Ciliary ganglion with nNOS-negative perikarya. (D) Ciliary ganglion with an nNOS-positive perikaryon (arrow). The diameter of the nNOS-positive perikaryon is markedly smaller than that of an adjacent nNOS-negative perikaryon (asterisk). (E, F). Perikarya in the pterygopalatine ganglia are intensely labelled for both NADPH-D (E) and nNOS (F). Scale bars: A, E, 60 µm; B, 20 µm; C, 30 µm; D, F, 10 µm.

Table 1.

Percentage of NOS/NADPH-D-stained perikarya

| Ciliary ganglion | 1% |

| Pterygopalatine ganglion | 70–75% |

| Superior cervical ganglion | 0 |

| Trigeminal ganglion | 18% |

Fig. 2.

NADPH-D (A–C) and nNOS (D) in human trigeminal ganglia. (A) 18% of perikarya are nNOS/NADPH-D positive (arrows). The cells are equally distributed throughout the different portions of the ganglion. (B) Staining intensity for NADPH-D varies between individual trigeminal ganglion cells, which are intensely or moderately labelled. (C) Double staining of B against nNOS shows a distinct correlation in labelling intensity with NADPH-D staining. Scale bars: A, 200 µm; B, C, 20 µm.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of diameters of NADPH-D/nNOS-positive perikarya in seven trigeminal ganglia from six human donors.

Discussion

Our findings strongly indicate that post-ganglionic neurons in the superior cervical ganglion do not synthesize nitric oxide and do not contribute to the ocular extrinsic nitrergic innervation in the human eye. These results corroborate data by Tajti et al. (1999b); similar to our data, they did not observe nNOS-immunoreactivity in superior cervival perikarya. The NADPH-D/nNOS-positive varicose axons in the superior cervical ganglion observed in our study might be of preganglionic origin. Comparable axons were observed in superior cervical ganglia of rats (Morris et al. 1993) and have been shown to derive from the intermediolateral horn of the spinal cord, which contains NADPH-D-positive neurons (Okamura et al. 1995). As in the superior cervical ganglion, we did not observe nNOS/NADPH-D staining in the vast majority of ciliary ganglion perikarya. However, we did observe in some ciliary ganglia several solitary and strongly nNOS/NADPH-D-positive perikarya, which were highly infrequent (less than 1%) and considerably smaller in size than regular ciliary perikarya. Comparable findings were reported by Demer et al. (1995). Because of the small size of ciliary nNOS/NADPH-D ganglion cells, we assume that their axon is not myelinated and does not contribute to the cholinergic innervation of the ciliary muscle, which is otherwise the case for most of ciliary ganglion perikarya. The specific function and site of projection of small ciliary nNOS/NADPH-D ganglion cells are unclear. In contrast to findings in ciliary and superior cervical ganglia, a substantial number of nNOS/NADPH-D perikarya were found in pterygopalatine ganglia, which are very likely the main source of extrinsic autonomous nitrergic nerves to the human eye. Regardless, the trigeminal ganglia also contained a substantial number of nNOS/NADPH-D perikarya, indicating that nitric oxide is among the neuroactive molecules that are released from peripheral afferent terminals in the eye. Quantitative analysis of trigeminal nNOS/NADPH-D perikarya indicates that most of them are of small or moderate size and probably nociceptive in nature. nNOS/NADPH-D trigeminal perikarya might play a role during the irritative response of the eye, as nitric oxide has been shown to activate C-fibres causing release of C-fibre neuropeptides during ocular inflammation (Wang et al. 1996, 1997).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by SFB 539 (TP BI.4 to E.R.T.). We thank Marco Gößwein for the expert processing of the light micrographs.

References

- Bergua A, Jünnemann A, Naumann GOH. NADPH-D reactive choroidal ganglion cells in the human eye. Klin. Mbl. Augenheilk. 1993;203:77–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1045651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Miller JM, Poukens V, Vinters HV, Glasgow BJ. Evidence for fibromuscular pulleys of the recti extraocular muscles. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1995;36:1125–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel RC, Johnson DA. Use of nonfat dry milk to block nonspecific nuclear and membrane staining by avidin conjugates. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1985;33:711–714. doi: 10.1177/33.7.2409130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügel C, Tamm ER, Mayer B, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Species differences in choroidal vasodilative innervation: evidence for specific intrinsic nitrergic and VIP-positive neurons in the human eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994;35:592–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügel-Koch C, Kaufman PL, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Association of choroidal ganglion cell plexus with the fovea centralis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994b;35:4268–4272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügel-Koch C, May CA, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Presence of a contractile cell network in the human choroid. Ophthalmologica. 1996;210:296–302. doi: 10.1159/000310728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanazawa T, Tanaka K, Chiba T, Konno A. Distribution and origin of nitric oxide synthase-containing nerve fibers in human nasal mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol. 1997;117:735–737. doi: 10.3109/00016489709113469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt P, Heinzel B, John M, Kastner M, Böhme E, Mayer B. Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent cytochrome-c reductase activity of brain nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:11374–11378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May CA, Fuchs AV, Scheib M, Lutjen-Drecoll E. Characterization of nitrergic neurons in the porcine and human ciliary nerves. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May CA, Neuhuber W, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Immunohistochemical classification and functional morphology of human choroidal ganglion cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:361–367. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R, Southam E, Gittins SR, Garthwaite J. NADPH-diaphorase staining in autonomic and somatic cranial ganglia of the rat. Neuroreport. 1993;4:62–64. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Umehara K, Tadaki N, Hisa Y, Esumi H, Ibata Y. Sympathetic preganglionic neurons contain nitric oxide synthase and project to the superior cervical ganglion: combined application of retrograde neuronal tracer and NADPH-diaphorase histochemistry. Brain Res. Bull. 1995;36:491–494. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00234-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödl F, De Laet A, Tassignon MJ. Intrinsic choroidal neurons in the human eye: projections, targets, and basic electrophysiological data. Invest. Ophthalmol.Vis. Sci. 2003;44:3705–3712. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanini M, de Martino C, Zamboni C. Fixation of ejaculated spermatozoa for electron microscopy. Nature. 1967;216:173–174. doi: 10.1038/216173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajti J, Moller S, Uddman R, Bodi I, Edvinsson L. The human superior cervical ganglion: neuropeptides and peptide receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 1999a;263:121–124. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajti J, Uddman R, Moller S, Sundler F, Edvinsson L. Messenger molecules and receptor mRNA in the human trigeminal ganglion. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1999b;76:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(99)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Flügel-Koch C, Mayer B, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Nerve cells in the human ciliary muscle. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical characterization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1995a;36:414–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Koch TA, Mayer B, Stefani FH, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Innervation of myofibroblast-like scleral spur cells in human and monkey eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1995b;36:1633–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Nitrergic nerve cells in the primate ciliary muscle are only present in species with a fovea centralis. Ophthalmologica. 1996;211:201–204. doi: 10.1159/000310789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm ER, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Origin and function of nitrergic nerves in the eye. In: Kashii S, Akaike A, Honda Y, editors. Nitric Oxide in the Eye. 1st. Tokyo: Springer Verlag; 2000. pp. 31–65. [Google Scholar]

- Uddman R, Tajti J, Moller S, Sundler F, Edvinsson L. Neuronal messengers and peptide receptors in the human sphenopalatine and otic ganglia. Brain Res. 1999;826:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Alm P, Hakanson R. The contribution of nitric oxide to endotoxin-induced ocular inflammation: interaction with sensory nerve fibres. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1537–1543. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Waldeck K, Grundemar L, Hakanson R. Ocular inflammation induced by electroconvulsive treatment: contribution of nitric oxide and neuropeptides mobilized from C-fibres. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:1491–1496. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]