Abstract

Chronic selective β1-adrenoceptor (β1AR) blocker treatment enhances the sensitivity of β2-adrenoceptor (β2AR) in human heart (Hall et al., 1990; 1991). To clarify the mechanism of the cross-sensitization between β1AR and β2AR, we determined whether the stimulatory G-protein (Gsα) function is increased in atria from β1AR-blocker treated patients compared with non-β-blocked patients, and investigated whether this change is caused by an alteration of post-translational modification of Gsα protein.

Gsα function was determined by reconstitution of human atrial Gsα into S49 cyc− cell membranes. In the reconstitution system, GTPγS stimulated cyclic AMP generation in a dose-dependent manner. Upon 10−4 M GTPγS stimulation, Gsα activity in the β1AR-blocker, atenolol, treated group (78.2±10.3 pmol cyclic AMP mg−1 min−1 10−3) was 65% higher than that in non-β-blocked patients (47.3±6.3 pmol cyclic AMP mg−1 min−1 10−3, n=15, P=0.02).

Isoelectric point (pI) values of Gsα were measured by two dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-E) and the amount of each isoform quantified by image analysis of a Western blot of the gel using specific antibody. Multiple isoforms of Gsα were detected by 2D-E with different pI values. There were no significant differences between the groups of patients in either pI values or the proportions of the acidic isoforms of Gsα to the main basic form (n=12, P>0.05).

The results suggest that chronic β1AR-blockade enhances Gsα function in human atrium, and this may account in part for the hypersensitivity of β2AR and other Gs-coupled receptors during β1AR-blockade. The increased Gsα function is unlikely to be caused directly by blockade of protein kinase A phosphorylation of Gsα protein.

Keywords: β1-adrenoceptor blockade, G-protein, S49 cyc− reconstitution, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, receptor cross-regulation, human

Introduction

β-Adrenergic receptor (βAR) antagonists are widely used for the treatment of ischaemic heart disease, hypertension and heart failure. To minimize the adverse effects of β2AR-blockade, so-called cardio-selective (β1AR selective) βAR-blockers were introduced. However, subsequent evidence has shown that human atrium and ventricle contain an appreciable proportion of functional β2AR (Kaumann & Lemoine, 1987; Del Monte et al., 1993), and that, moreover, chronic treatment of patients with a β1AR-selective blocker causes marked enhancement of β2AR mediated atrial inotropic responses (Hall et al., 1990). The β2AR hypersensitization by β1AR blockade has been confirmed in vivo, where there is a 6 fold increase of the potency of salbutamol during intra-coronary infusion of this drug in patients receiving a β1AR-blocker (Hall et al., 1991). This phenomenon may benefit the patients with chronic heart failure by improving the pumping function during β1AR-blockade, but on the other hand, in patients with myocardial infarction the increased sensitivity to β2AR stimulation is likely to increase heart rate and myocardial oxygen consumption, thereby increasing the risks of arrhythmia and the extent of infarction.

When the βAR is occupied by an agonist, the resulting conformational change of the receptor activates the stimulatory heterotrimeric G-protein (Gs) to bind guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to its α-subunit. The Gsα-GTP complex then stimulates adenylyl cyclase (AC) to generate the second messenger cyclic AMP. Cyclic AMP subsequently gives rises to the activation of protein kinase A (PKA) which can phosphorylate a series of proteins. Elements involved in Gs-mediated signal transduction cascade are obvious targets for clarifying the mechanism of cross regulation between receptors coupled to adenylyl cyclase. In support of this suggestion is the evidence that two other Gs-coupled receptors, the 5-HT4-receptor and histamine H2-receptor, mediate inotropic responses in human atria which are potentiated by chronic β1AR-blockade (Sanders et al., 1995; 1996).

Indirect evidence for the involvement of the coupling mechanism in the receptor ‘cross-talk' comes also from the findings that there is no increase in β2AR density or affinity for ligands in β1AR blocked right atria, nor any change in the cellular sensitivity to exogenously applied cyclic AMP analogues (Hall et al., 1990). However no quantitative change has been found following β1AR-blocker treatment in the level of G-protein subunits (Gsα, Giα, Gβ) (Ferro et al., 1993) or the mRNA of the four splice variants of Gsα and Gi2α (the principle cardiac Gi protein) (Jia et al., 1995; Monteith et al., 1995). A variety of post-translational modifications of Gsα have been reported, such as phosphorylation and ribosylation, some occurring in response to cyclic AMP stimulation (Yamane et al., 1993; Degtyarev et al., 1993; Linder et al., 1993; Pyne et al., 1993). These modifications therefore raise the possibility of a functional feedback regulation of Gs function without changes in its transcription.

The present study was designed to measure Gs protein function by reconstitution of Gsα protein from human atrium into S49 cyc− lymphoma cell membranes. In this system, S49 cyc− cells are genetically deficient in Gsα and therefore lack Gs-mediated adenylyl cyclase activity. The addition of solubilized Gsα to cyc− cell membranes can restore Gs-mediated adenylyl cyclase activity. The rate of cyclic AMP generation theoretically reflects pure Gs function.

As a consequence of the activation of the Gs-mediated signal transduction pathway, the phosphorylation status and possibly function of numerous proteins may be increased by PKA. Gsα can be phosphorylated by PKA in vitro (Pyne et al., 1992). It is not clear whether this occurs in vivo. However we have reported that the serine+ variants of Gsα , which might be more prone to PKA phosphorylation, have a more acidic iso-electric point (pI) – consistent with in vivo modification by phosphorylation (Monteith et al., 1995). In the present study, two dimensional gel electrophoresis was employed to determine whether there is any change in the pI value of Gsα protein from human atria after chronic treatment with a β1AR-blocker.

Methods

Patients

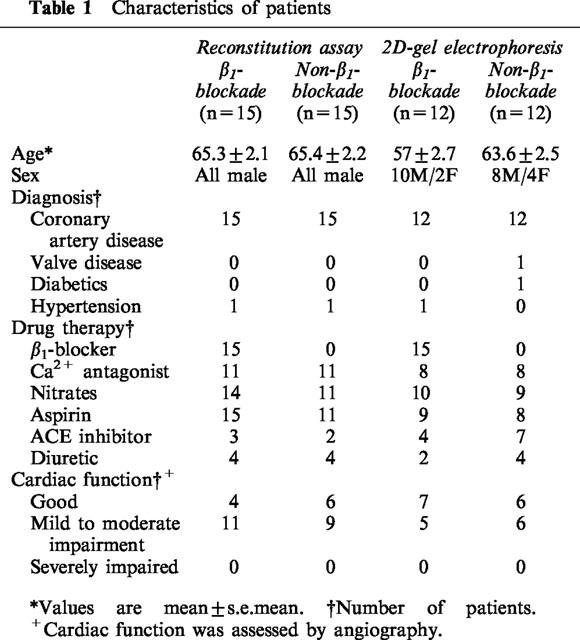

Right atrial appendage (RAA) was obtained immediately following its routine removal from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, at the time of institution of cardiopulmonary bypass. Premedication was with papaveretum and hyoscine; anaesthesia was induced with midazolam, fentanyl and propofol, with pancuronium as muscle relaxant. Propofol infusion was used for maintenance of anaesthesia. RAA were received from 54 patients; 30 samples were used for Gs functional assay, and the other 24 were used for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Half the samples for each assay were from patients receiving chronic β1AR-blocker atenolol treatment (50 mg day−1, over 1 month) at the time of surgery, and half from non-β-blocked patients. Although the choice was not randomized, it tended to reflect individual referring physicians' preference for β-blockade or Ca2+-blockade as secondary treatment in patients already receiving nitrates. Patients were matched as far as possible in terms of age, sex and diagnosis in both sets of studies (Table 1). Other drug therapy included aspirin, calcium channel antagonists, diuretics and nitrates. Tissue samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen as soon as they were removed during the heart operation and stored at −70°C until use. The use of tissue routinely removed and discarded during surgery was approved by the local research ethics committee without patients written consent being required.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

Cell culture and preparation of S49 cyc− cell membranes

S49 cyc− lymphoma cells were grown in suspension culture in HEPES buffered Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium that had been supplemented with antibiotics (100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin), antimycotic (0.25 μg ml−1 amphotericin B) and 5% foetal calf serum. The population density was maintained at about 106 cells ml−1. 2.4×109 cyc− cells were harvested, the cells pelleted by centrifuging at 1000×g for 20 min at 4°C and washed twice with HEPES buffer (HEPES 50 mM, EDTA (pH 8.0) 5 mM). The cell pellet was suspended in HEPES buffer and homogenized in a ground glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant collected as supernatant 1. The pellet was re-homogenized in HEPES buffer and the supernatant collected as supernatant 2. Supernatants 1 and 2 were pooled, filtered through four layers of gauze and centrifuged at 48,000×g for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in HEPES buffer. Protein concentration was measured in 96-well plates using the Bio-Rad protein assay with bovine serum albumin as standard. The cyc− cell membrane preparation with a final concentration of ∼2 mg ml−1 was stored in separate aliquots at −70°C.

Cholate extraction of Gs protein from human right atrium

Right atrial appendage tissues (40–200 mg) were debrided of fat and connective tissue and homogenized in buffer A (170 μl 100 mg−1 tissue, HEPES (pH 8.0) 10 mM, EDTA 1 mM, benzamidine 3 mM and 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin). Sodium cholate and β-mercaptoethanol were added to the homogenate to give a final concentration of 1% and 20 mM respectively. After vortexing on ice for 60 min the homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000×g for 60 min at 4°C. Protein concentration of the supernatant was measured as above to be 10 μg μl−1 on average, and the remainder aliquoted and stored at −70°C until use.

Reconstitution of Gsα activity in S49 cyc− lymphoma membrane

Cholate extracts were diluted in buffer A. Frozen cyc− membranes were resuspended in fresh HEPES buffer. Cyc− membranes (40 μg) and RAA cholate extracts were incubated together in a 100 μl reconstitution mix containing cyclic AMP 1 mM, ATP 0.1 mM, creatine phosphate 20 mM, 40 U creatine phosphokinase, 40 U myosin kinase, GTP 0.05 mM HEPES 50 mM, EGTA 0.1 mM, MgCl2 10 mM, 0.1 mg ml−1 BSA and 5 μCi [α-32P]-ATP. After 40 min incubation in a water bath, the reaction was terminated by adding 100 μl of 40 mM ATP and heating at 90°C for 5 min. The cyclic AMP formed was isolated by sequential chromatography using a Dowex 50 cation exchange and neutral alumina column. Recovery of cyclic AMP was monitored by the addition of [3H]-cAMP to each tube. The [32P]- and [3H]-cAMP eluted from the alumina were quantified by double-isotope liquid-scintillation spectroscopy. A concentration curve of Guanosine-5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate (GTPγS) stimulated adenylyl cyclase activities was examined in an atrial sample with triplicate determinations of each concentration of GTPγS, and 10−4 M GTPγS stimulated cyclic AMP generation with different amount of membrane protein (12–70 μg) was tested. Results were expressed as the amount of cyclic AMP formed per minute per milligram of protein.

Membrane preparation from human right atrium

Samples of right atrial appendage were debrided of fat and connective tissue. The remaining material was placed in ice cold buffer B (β-glycerophosphate 10 mM, HEPES 10 mM, benzamidine 2 mM, PMSF 1 mM, 5 μl mg−1 tissue), minced with scissors and homogenized using a Polytron at maximum speed (setting 10) for 5×5 s. The homogenate was centrifuged at 2000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 48,000×g for 15 min at 4°C to obtain a crude plasma membrane fraction that was resuspended in buffer B and stored in separate aliquots at −70°C. Protein concentration was measured as above.

Isoelectric focusing (IEF)

Two dimensional electrophoresis was performed according to the method of O'Farrel (1975) using the MINI-PROTEAN II 2-D CELL system. IEF gel monomer solution was made containing 9.2 M urea, 2% NP40, 0.018% ammonium persulphate, 0.025% TEMED, 2% pH 3–10 ampholyte, 1% pH 5–7 ampholyte, 1% pH 3.5–5 ampholyte and 1% pH 7–9 ampholyte. IEF tube gels were cast in glass capillary tubes of 10 cm long and 1 mm in diameter. Samples of crude plasma membrane were mixed with an equal volume of first dimensional sample buffer (9.5 M urea, 4% NP40, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.4% pH 3.5–10 ampholyte, 1.6% pH 5–7 ampholyte) and incubated at room temperature for 10–15 min. The tube gel was pre-run at 200 V for 10 min, 300 V for 15 min and 400 V for 15 min with the upper chamber running buffer NaOH 20 mM (degassed) and lower chamber running buffer H3PO4 10 mM. About 10 μg membrane proteins (25 μl) were loaded onto the tube gel. On the top of the sample, 30 μl sample overlay buffer (9 M urea, 0.8% pH 5–7 ampholyte, 0.2% pH 3–10 ampholyte) was loaded. The gel was run at 500 V for 10 min, 750 V for 3.5 h and 2 KV for 30 min. After IEF was completed, the tube gels were ejected into equilibration buffer (Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) 0.0625 M, 2.3% (w v−1) SDS, 2-mercaptoethanol 10 mM, 10% (w v−1) glycerol) and frozen at −70°C until the second-dimension was run.

For measurement of the pH gradient along the tube gel, Pharmacia 2-D Electrophoresis Calibration Kit was used. Carbamylated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) protein was included with each atrial sample prior to iso-electric focusing and SDS–PAGE. The series of spots (approximately 34 spots) between pI values of 4.9–7.1 were visualized by Ponsau S staining of the nitro-cellulose membrane after Western blotting. The pI value of Gsα was calculated by comparison with these standard protein spots.

SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting

IEF gel strips were loaded directly on the top of the slab gel, excluding any air bubbles. The second-dimension separation was carried out at room temperature with a mini stacking gel (1×8×0.05 cm, 4%T) and separating gel (5×8×0.05 cm, 10%T) system. Voltage was set at 200 V and current at maximum.

Following electrophoresis, immunoblotting of Gsα protein was performed as described previously (Monteith et al., 1995). Briefly, proteins were electro-blotted onto a nitro-cellulose membrane for 1 h at 0.8 mA cm−2 with LKB117-250 Novablot apparatus. After blocking the non-specific binding sites by immersing in 5% dried milk (Marvel) for 30 min, the membrane was incubated at room temperature with anti-Gsα antiserum (1 : 750) for 2 h. This antiserum was generated against a synthetic GSα C-terminal decapeptide (RMHLRQYELL) and its characterization has been described previously (Miligan & Unson, 1989; Ohisalo et al., 1989). After washing with 0.1% Tween-20 (v v−1) made in Tris-buffer saline (TBS, NaCl 200 mM, Tris-HCl, (pH 7.4) 50 mM), the membrane was then incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-labelled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (1 : 500 dilution). After the membrane was washed again, G-protein dots were visualized by incubating with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents.

Quantification of Gsα protein

There was inadequate RAA protein to permit combined Gsα function and mass quantification except in four β-blocked and seven non β-blocked patients. Quantification was performed by 1-D Western blot, as previously described (Ferro et al., 1993), and results expressed in arbitrary optical density units. This permitted an assessment of Gsα specific activity in the 11 samples.

Reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was from Life Technologies (Paisley, Scotland, U.K.). Foetal calf serum was from Globepharm. [α-32P]-ATP, [3H]-cAMP and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents were from Amersham (Amersham International plc., U.K.). Anti-Gsα antiserum was kindly donated by Professor G. Milligan (Molecular Pharmacology Group, Department of Biochemistry, University of Glasgow, Scotland, U.K.). Horseradish Peroxidase-labelled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin was from DAKO (Denmark). Protein assay kit was from Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd, Herculaes, CA, U.S.A.). 2-D Electrophoresis Calibration Kit was from Pharmacia (Pharmacia Inc, U.S.A.). Other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Statistics

All data were expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Statistical comparison of the reconstituted Gsα activity and the pI value between β1AR-blocked and non-β-blocked samples were by means of unpaired Student's t-test. The changes in the proportions of the acidic isoforms of Gsα to the main basic form after β1AR-blockade was assessed by a multiple regression analysis incorporating patients' ages and estimated left ventricular function. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Gsα activity in cyc− reconstitution assay

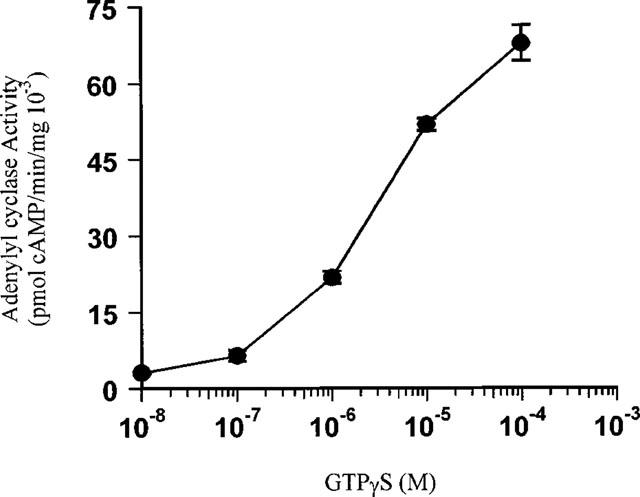

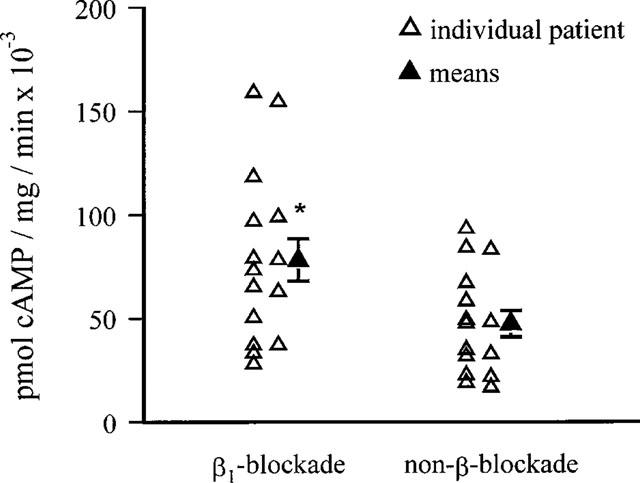

GTPγS stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in cyc− cell membranes was restored after combination with atrial extracts containing human Gsα. Cyclic AMP generation was dose-dependent up to the maximal concentration used of 10−4 M GTPγS (Figure 1). 10−4 M GTPγS-stimulated cyclic AMP generation varied linearly with the amount of membrane protein used up to 28 μg. Fifteen micrograms membrane protein was available from all RAA, and was used for the comparison of Gsα activity between β1AR-blocked and non-β-blocked human atria. Cholate extracts were diluted before addition to the reconstitution mix, and in the absence of S49 cell membranes, restored negligible Gsα mediated adenylyl cyclase activity upon GTPγS stimulation (data not shown). Reconstituted Gsα activity in the presence of 10−4 M GTPγS was 78.2±10.3 pmol cyclic AMP mg−1 min−1 10−3 in 15 atenolol treated patients, which was 65% greater than in 15 non-β-blocked patients, 47.3±6.3 pmol cyclic AMP mg−1 min−1 10−3 (P=0.02, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent increase of Gsα activity by GTPγS stimulation in the Gsα reconstitution assay. Data are mean±s.e.mean of triplicate determinations from one patient's right atrial appendage.

Figure 2.

Comparison of atrial Gsα activity between β1AR-blocked and non-β-blocked patients. Gsα activity was measured as the increase in adenylyl cyclase activity in S49 cyc− cell membranes in the presence of 10−4 M GTPγS. Data are represented as means of triplicate determinations of each patients' sample (open triangles) and means of data from 15 patients' right atrial appendage (solid triangle, mean±s.e.mean). *P=0.02.

In the 11 patients where the Gsα protein could be quantified, there was a trend for higher specific activity in the β1-blocked atria (13.0±2.1 arbitrary units) than that in the non-β-blocked atria (7.3±2.3), although this was not a significant difference in the small number of samples.

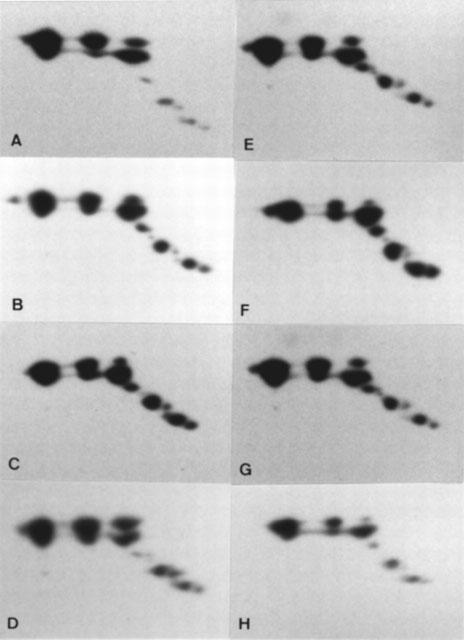

2D-gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting

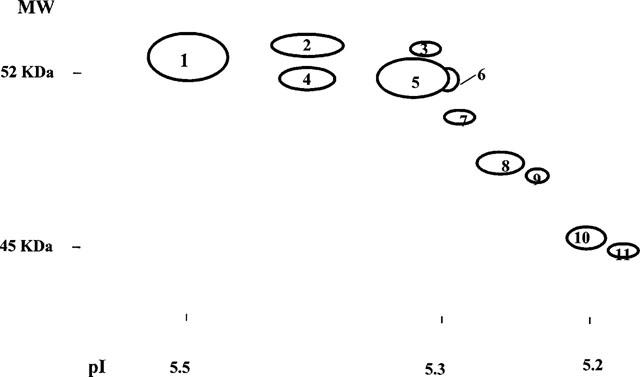

Typical 2D-patterns of Gsα from human atrium are shown in Figures 3 and 4. A total of 11 forms of Gsα were detected. Those at MW 52 KDa correspond to Gsα long isoform (GsαL) and those at 45 KDa to Gsα short isoform (GsαS). The pI for the GsαL residues (pI 5.53±0.01) were less acidic than GsαS (pI 5.19±0.01, P<0.001), which confirms the previous finding. The densest and most basic spot was taken as the reference point and assumed to be the unmodified Gsα.

Figure 3.

Sketchgraph shows the 2D-pattern of the Gsα protein from human atria. Membrane proteins were separated horizontally by iso-electric point and vertically by mass. Gsα was detected by immunoblotting with specific antibody. The dots were numbered from 1–11.

Figure 4.

Comparison of two-dimensional pattern of Gsα in right atrial appendage between patients receiving β1AR-blocker and non-β-blocker treatment. Four typical 2D-patterns of Gsα from each group are shown here. (A, B, C and D) β1AR-blockade; (E, F, G and H) non-β-blockade.

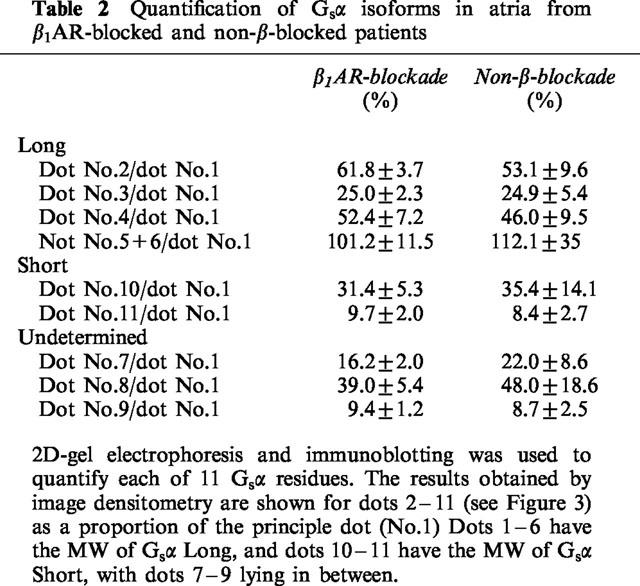

The 2D-pattern of Gsα from the atria of 12 atenolol treated and 12 matched non-β-blocked patients were compared. The patterns were very reproducible. The pI value of the major isoforms of GsαL and GsαS were 5.53±0.01 and 5.19±0.01 for the β1AR-blocked group, compared to 5.53±0.01 and 5.17±0.01 for the non-β-blocked group, (P>0.05, Figure 4). In order to determine whether the relative amount of these isoforms changed after β1AR-blockade, the isoforms on the 2D-pattern from each individual were numbered from 1–11 (Figure 3) and were quantified by laser-densitometry, and the ratio of each dot to the main basic dot (number 1) calculated. The results are shown in Table 2. No significant differences were observed in the proportions of the acidic residues of Gsα relative to the main basic residue between these two groups of patients (P>0.05).

Table 2.

Quantification of Gsα isoforms in atria from β1AR-blocked and non-β-blocked patients

Discussion

Previous studies showed that chronic β1-blocker treatment causes a several fold increase in the potency of β2AR-agonists and antagonists at adenylyl cyclase coupled receptors (Hall et al., 1990; 1991; 1993; Sanders et al., 1995; 1996). These observations have been made both in vitro and in vivo, the most striking being a 6 fold increase in potency of sulbutamol when infused into the right coronary artery of atenolol treated patients. This sensitization occurs with no increase in receptor number or occupation, or of cyclic AMP responsiveness (Hall et al., 1990; Brodde, 1991), pointing to enhanced coupling of the receptors to adenylyl cyclase through Gs. However in several studies of Gsα and β subunit mRNA and protein levels, no overall differences in levels were found (Ferro et al., 1993; Jia et al., 1995; Monteith et al., 1995). The present study shows that there is indeed an increase in Gs function in the atria of β1AR-blocked patients, but fails to elucidate the mechanism.

There was reason to expect that β1AR-blockade might influence post-translational modification of G-proteins. In the heart, the βAR–G-protein–adenylyl cyclase signal transduction pathway is normally under a high level of adrenergic stimulation, which results in tonic PKA activity. There is evidence that Gsα can be phosphorylated through PKA in vitro (Pyne et al., 1992), and it is plausible therefore that the PKA activation could cause Gsα to be phosphorylated in vivo. Chronic blockade of β1AR interrupts the activation cascade and would therefore reverse any PKA stimulated phosphorylation of Gsα. Other kinds of post-translational modification of Gsα, such as palmitoylation and ADP-ribosylation, could also be affected in the same way, especially the latter which has been shown to be activated by cyclic AMP (Yamane et al., 1993; Degtyarev et al., 1993; Linder et al., 1993; Pyne et al., 1992). We have ourselves found indirect evidence that sympathetic tone in vivo does influence the post-translational modifications of Gsα identified by 2D-pattern changes. The finding was that the proportion of some of the acidic isoforms of GsαL is much lower in saphenous vein than in the heart (Wang & Brown, 1996), consistent with the much lower sympathetic tone in the former. The lack of difference in the present study of pI values in atria of Gsα between β1AR-blocked and non-β-blocked patients implies that Gsα is unlikely to be modified directly by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A in vivo. It is conceivable that such phosphorylation has still occurred through the β2AR, but in a small number of atria from patients receiving non-selective β-blockade, a similar 2D-pattern is still observed.

The precise mechanisms that result in the increase of Gsα activity remain intriguing. The reproducibility of the 2D-gel electrophoresis means that we could have readily detected changes in modification as great as the increase in Gs function present. The possibility of changes of some post-translational modifications that do not alter the pI values of the Gsα protein could not however be excluded.

There was substantial overlapping of the Gsα function data between the two groups of patients, even though the means were significantly different. This overlapping, together with the modest mean increase in Gsα function raises the question whether this difference is sufficient to explain the 5–10 fold increase of the inotropic response of the atria from β1AR-blocked patients (Hall et al., 1990; 1991). Since the signal transduction cascade is an amplification process, we would not expect 1 : 1 equivalence between G-protein activity and the final physiological response, but we have not attempted to measure the gearing. The increased Gsα function following β1AR-blockade shows that receptor coupling to adenylyl cyclase is one site of receptor cross talk, but it is likely this is not the unique change which contributes to the increased β2AR sensitivity. At the receptor level, chronic administration of bisoprolol, a β1AR-selective blocker, to pigs has been reported to cause a reduction in left ventricular β-adrenergic receptor kinase (βARK) activity (Ping et al., 1995). The reduction of βARK expression was also observed in mouse model with long-term administration of atenolol (laccarino et al., 1998). Beyond Gsα in the transduction pathway, there are up to nine types of adenylyl cyclase that have been identified so far (Krupinski et al., 1989; Gao & Gilman, 1991; Ishikawa et al., 1992; Premont et al., 1992; Katsushika et al., 1992; Watson et al., 1994). Of these at least four types are present in the heart (AC IV, V, VI and VII) (Ishikawa & Homcy, 1997; Iyengar, 1993). Are these cardiac adenylyl cyclases coupled equally to different receptors or are some of the adenylyl cyclases switched on or off upon β1AR-blockade? Determination of the gene expression of each subtype of the adenylyl cyclases upon β1AR-blockade is ongoing. The multiple isoforms of the adenylyl cyclase present in the heart, and evidence of compartmentalization of cyclic AMP activation (Zhou et al., 1997) limit the value of comparison of the overall adenylyl cyclase activity between the two groups of patients. Cross-talk between the β2AR and other receptors or cell signalling systems has been described in the organ bath. We believe these observations are not relevant to the β2AR cross-talk we observe, which develops over several hours or days.

Gsα reconstitution study is a classic method to test Gsα function with the advantage of the availability of S49 cyc− cell line genetically deficient in Gsα. The early experiments with the method by Ross and Gilman led to the discovery of Gsα (Haga et al., 1977; Ross & Gilman, 1977). However, when used to test Gsα function, the disadvantage is that cholate extraction causes subunit dissociation of G-protein. Therefore the method would under-estimate changes related to subunit interaction, for instance if reduced Gs activation during β1AR-blockade results in a higher proportion of intact trimeric Gs-protein in the atrial membrane.

In summary, chronic β1AR-blockade can enhance Gsα function in human atrium, explaining at least partially the sensitization of β2AR mediated responses by β1AR-blockade. The lack of difference in pI values of Gsα between β1AR-blocked and non-β-blocked atria suggests that the increased Gsα activity is not due to a change in the phosphorylation status of Gsα protein consequent on the reduced activity of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the cardiac surgeons and theatre staff at Papworth Hospital for providing us with tissues from their patients. This work was supported by a project grant from the Medical Research Council.

Abbreviations

- β1AR

β1-adrenoceptor

- β2AR

β2-adrenoceptor

- βARK

β-adrenergic receptor kinase

- cyclic AMP

adenosine 3′ : 5′-cyclic monophosphate

- CPK

carbamylated creatine phosphokinase

- 2D-E

two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- ECL

enhanced chemiluminescence

- Gβ

β-subunit of G-protein

- Giα

α-subunit of inhibitory G-protein

- Gs

stimulatory heterotrimeric G-protein

- Gsα

α-subunit of stimulatory G-protein

- GsαL

the long isoform of the stimulatory G-protein α-subunit

- GsαS

the shot isoform of the stimulatory G-protein α-subunit

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- GTPγS

guanosin-5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate

- IEF

isoelectric focusing

- PKA

protein kinase A

- pI

isoelectric point

- RAA

right atrial appendage

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

References

- BRODDE O.E. β1-and β2-adrenoreceptors in human heart: properties, function, and alterations in chronic heart failure. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:203–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEGTYAREV M.Y., SPIEGEL A.M., JONES T.L.Z. Increased palmitoylation of the Gs protein α subunit after activation by the β-adrenergic receptor or cholera toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:23769–23772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEL MONTE F., KAUMANN A.J., POOLE-WILSON P.A., WYNNE D.G., PEPPER J., HARDING S.E. Coexistence of β1 and β2-Adrenoreceptors in single myocytes from human ventricle. Circulation. 1993;88:854–863. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRO A., PLUMPTON C., BROWN M.J. Is receptor cross-regulation in human heart caused by alterations in cardiac guanine nucleotide-binding proteins. Clin. Sci. 1993;85:393–399. doi: 10.1042/cs0850393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO B., GILMAN A.G. Cloning and expression of a widely distributed (type IV) adenylyl cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:10178–10182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAGA T., ROSS E.M., ANDERSON H.J., GILMAN A.G. Adenylate cyclase permanently uncoupled from hormone receptors in a novel variant of S49 mouse lymphoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1977;74:2016–2020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.5.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL J.A., FERRO A., DICKERSON J.E., BROWN M.J. Beta adrenoceptor subtype cross regulation in the human heart. Br. Heart J. 1993;69:332–337. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.4.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL J.A., KAUMANN A.J., BROWN M.J. Selective β1-adrenoreceptor blockade enhances positive inotropic responses to endogenous catecholamines mediated through β2-adrenoreceptors in human atrial myocardium. Circ. Res. 1990;66:1610–1623. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL J.A., PETCH M.C., BROWN M.J. In vivo demonstration of cardiac β2-adrenoreceptor sensitisation by β1-antagonist treatment. Circ. Res. 1991;9:959–964. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IACCARINO G., TOMHAVE E.D., LEFKOWITZ R.J., KOCH W.J. Reciprocal in vivo regulation of myocardial G protein-coupled receptor kinase expression by β-adrenergic receptor stimulation and blockade. Circulation. 1998;98:1783–1789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIKAWA Y., HOMCY C.J. The adenylyl cyclase as integrators of transmembrane signal transduction. Circ. Res. 1997;80:297–304. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIKAWA Y., KATSUSHIKA S., CHEN L., HALNON N.J., KAWABE J., HOMCY C. Isolation and characterisation of a novel cardiac adenylylcyclase cDNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13553–13557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IYENGAR R. Molecular and functional diversity of mammalian Gs-stimulated adenylyl cyclases. FASEB J. 1993;7:768–775. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.9.8330684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIA H., MONTEITH S., BROWN M.J. Expression of the α- and β-subunits of the stimulatory and inhibitory G-proteins in β1-adrenoreceptor-blocked and non-β-adrenoreceptor-blocked human atrium. Clin. Sci. 1995;88:571–580. doi: 10.1042/cs0880571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATSUSHIKA S., CHEN L., KAWABE J., NILAKANTAN R., HALNON N.J., HOMCY C.J., ISHIKAWA Y. Cloning and characterisation of a sixth adenylyl cyclase isoform: Type V and VI constitute a subgroup within the mammalian adenylyl cyclase family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:8774–8778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUMANN A.J., LEMOINE H. β2-Adrenoreceptor-mediated positive inotropic effect of adrenaline in human ventricular myocardium. Quantitative discrepancies with binding and adenylate cyclase stimulation. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1987;335:403–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00165555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRUPINSKI J., COUSSEN F., BAKALYAR H.A., TANG W.J., FEINSTEIN P.G., ORTH K., SLAUGHTER C., REED R.R., GILMAN A.G. Adenylyl cyclase amino acid sequence: possible channel- or transporter-like structure. Science. 1989;244:1558–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.2472670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDER M.E., MIDDLETON P., HEPLER J.R., TAUSSIG R., GILMAN A.C., MUMBY S.M. Lipid modification of G Proteins: α subunits are palmitoylated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:3675–3679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLIGAN G., UNSON C.G. Persistent activation of the α-subunit of Gs promotes its removal from the plasma membrane. Biochem. J. 1989;260:837–841. doi: 10.1042/bj2600837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTEITH M.S., WANG T., BROWN M.J. Differences in transcription and translation of long and short Gsα, the stimulatory G-protein, in human atrium. Clin. Sci. 1995;89:487–495. doi: 10.1042/cs0890487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'FARREL P.H. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHISALO J.J., VIKMAN H.L., RANTA S., HOUSLAY M.D., MILLIGAN G. Adipocyte plasma-membrane Gi and Gs in insulinopenic diabetic patients. Biochem. J. 1989;262:289–292. doi: 10.1042/bj2640289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PING P., GELZER-BELL R., ROTH D.A., KIEL D., INSEL P.A., HAMMOND H.K. Reduced β-adrenergic receptor activation decrease G-protein expression and β-adrenergic receptor kinase activity in porcine heart. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:1271–1280. doi: 10.1172/JCI117777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PREMONT R.T., CHEN J., MA H., PONNAPALLI M., IYENGAR R. Two members of a widely expressed subfamily of hormone-stimulated adenylyl cyclases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:9809–9813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PYNE N.J., FREISSMUTH M., PYNE S. Phosphorylation of recombinant spliced variants of the α-sub-unit of the stimulatory guanine-nucleotide binding regulatory proteins (Gs) by the catalytic sub-unit of protein kinase A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;186:1081–1086. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90857-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PYNE N.J., GRADY M., STEVENS P. Phorbol ester (PMA) challenge of tracheal smooth muscle cells and its effect upon adenylyl cyclase, Gs and intracellular cyclic AMP. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:74. [Google Scholar]

- ROSS E.M., GILMAN A.G. Reconstitution of catecholamine-sensitive adenylate cyclase activity: interaction of solubilized components with receptor-replete membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1977;74:3715–3719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDERS L., LYNHAM J.A., BOND B., DEL MONTE F., HARDING SE., KAUMANN A.J. Sensitisation of human atrial 5-HT4 receptors by chronic β-blocker treatment. Circulation. 1995;92:2526–2539. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDERS L., LYNHAM J.A., KAUMANN A.J. Chronic β-adrenoreceptor sensitises the H1 and H2 receptor systems in human atrium: role of cyclic nucleotides. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353:611–670. doi: 10.1007/BF00167185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG T., BROWN M.J. Effects of β-adrenoreceptor blockade on Gsα isoforms in human atrium and blood vessels. Clin. Sci. 1996;35:2. [Google Scholar]

- WATSON P.A., KRUPINSKI J., KEMPINSKI A.M., FRANKENFIELD C.D. Molecular cloning and characterisation of the Type VII isoform of mammalian adenylyl cyclase expressed widely in mouse tissues and in S49 mouse lymphoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28893–28898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMANE H.K., FUNG B.K.K. Covalent modification of G-proteins. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1993;32:201–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU Y.Y., CHENG H., BOGDANOV K.Y., HOHL C., ALTSCHULD R., LAKATTA E.G., XIAO R.P. Localized cAMP-dependent signaling mediates beta 2-adrenergic modulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:H1611–H1618. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]