Abstract

Adenosine is a depressant in the central nervous system with pre- and postsynaptic effects. In the present study, intracellular recording techniques were applied to investigate the modulatory effects of adenosine on projection neurons in the lateral rat amygdala (LA), maintained as slices in vitro.

Adenosine reversibly reduced the amplitude of a fast inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) that was evoked by electrical stimulation of the external capsule and pharmacologically isolated by applying an N-methyl-D-aspartate and non-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, DL-(−)-2-amino-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid and 6,7-Dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, respectively, and the γ-aminobutyric acidB (GABAB) receptor antagonist CGP 35348. The postsynaptic potential that remained was abolished by locally applying bicuculline.

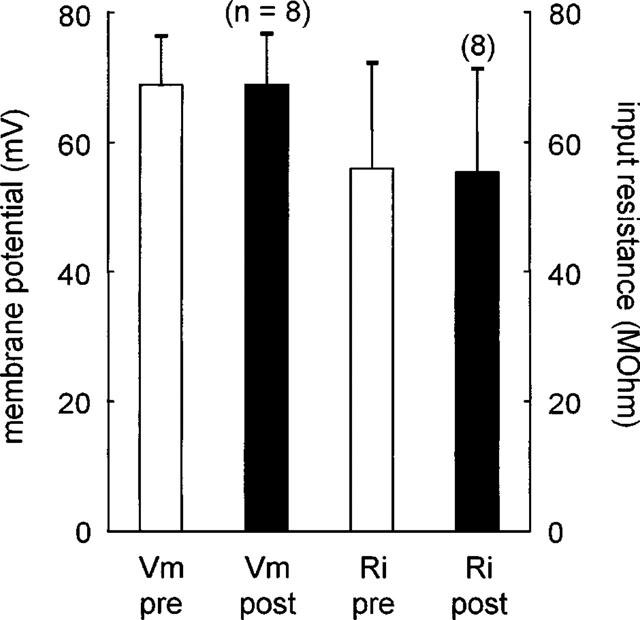

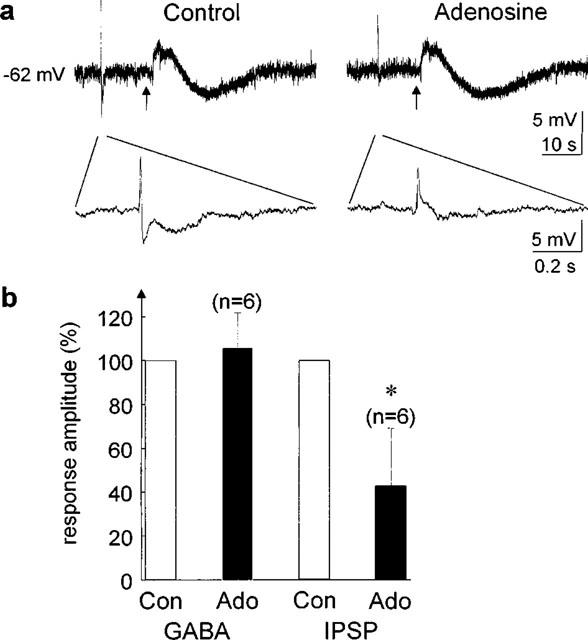

Adenosine reduced the amplitude of the fast IPSP on average by 40.3%. It had no significant effect on responses to exogenously applied GABA, on membrane potential or on input resistance, suggesting that the site of action was at presynaptic inhibitory interneurons in the LA.

The response to adenosine was mimicked by the selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-cyclohexyladenosine and blocked by the selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine.

Neuronal responsiveness in the amygdala is largely controlled by inhibitory processes. Adenosine can presynaptically downregulate inhibitory postsynaptic responses and could exert dampening effects likely by depression of both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter release.

Keywords: Adenosine, amygdala, epilepsy, excitability, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), limbic system, presynaptic inhibition, neuromodulation, rat

Introduction

The amygdaloid complex consists of several related nuclei in the CNS and is involved in different functional contexts such as memory, learning, emotion, fear, and motivation (Aggleton, 1992; Gallagher & Chiba, 1996; LeDoux, 1995). Neurons in the amygdala contribute to symptoms of temporal lobe epilepsy and spread of seizure discharges in models of epilepsy (Gloor, 1992). The lateral amygdaloid nucleus is the first relay station for cortical and thalamic sensory input to the amygdala and projections to other amygdaloid nuclei (Pitkänen et al., 1997) and therefore plays a key role in synaptic integration within the amygdala. Neuronal responsiveness in the amygdala appears to be largely controlled by inhibitory processes (Lang & Paré, 1997), and unbalanced regulation of neuronal activity in the amygdala is thought to contribute to neurological disorders (as reviewed in Aggleton, 1992).

Several neurotransmitters have been shown to modulate excitatory neurotransmission in the lateral and basolateral amygdala (Cheng et al., 1998; Ferry et al., 1997; Stutzmann et al., 1998). However, studies examining the modulation of inhibitory neurotransmission have been sparse (Nose et al., 1991). Among the candidates that modulate synaptic activity, adenosine has been shown to be an important neuromodulator of synaptic processes in different neuronal systems, particularly as a sleep-wakefulness neuromodulator (Greene & Haas, 1991; Huston et al., 1996; Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997; Rainnie et al., 1994), under physiological and pathophysiological conditions such as epilepsy and hypoxia (Dragunow, 1988; Dunwiddie, 1985; Fredholm & Dunwiddie, 1988; Gerber et al., 1989; Greene & Haas, 1991; Kessey & Mogul, 1998 and references therein; Silinsky, 1989; Snyder, 1985; Thompson et al., 1992). Extracellular levels of adenosine in the brain are known to increase during high metabolic demand such as increased neuronal firing rates, hypoxia and seizure activity (Greene & Haas, 1991; Huston et al., 1996; Mitchell et al., 1993). Adenosine is known for its role in reducing the excitability of neurons in all major divisions of the CNS (Greene & Haas, 1991; Morton & Davis, 1997). Relatively little is known about the effects of adenosine on inhibitory neurotransmission (Kirk & Richardson, 1994; Nose et al., 1991; Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995; Umemiya & Berger, 1994).

Here, we studied the effects of adenosine on postsynaptic potentials evoked upon synaptic activation in spiny projection neurons (PNs) in a horizontal slice preparation of the lateral amygdala (LA) of the rat in vitro. In particular, the purpose was to examine the effect of adenosine on fast inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by GABA. Preliminary accounts of some of these results have been presented in abstract form (Heinbockel & Pape, 1998a,1998b).

Methods

Preparation of slices

Long Evans rats of either sex (postnatal days 25-P30) were deeply anaesthetized with halothane (Zeneca, Plankstadt, Germany) and rapidly decapitated. After craniotomy the brain was immediately removed and transferred into cold (4°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (mM: KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 26, MgSO4 2, dextrose 10.5, sucrose 268, CaCl2 2), bubbled with carbogen gas (95% O2, 5% CO2) to pH 7.4. Horizontal brain slices (500 μm) were cut on a vibratome (Model 1000, Ted Pella, Redding, CA, U.S.A.) and dissected to isolate the amygdala and adjacent brain regions. The slices were transferred to an interface-type recording chamber and maintained at 35±1°C during continuous superfusion with ACSF (20 min). The horizontal orientation of slices was shown to maintain a large proportion of intra-amygdaloid connections (von Bohlen und Halbach & Albrecht, 1998). Slices were allowed to equilibrate for at least 90 min prior to experiments during continous superfusion with a solution containing (mM): NaCl 126, KCl 2.5, MgSO4 2, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1.25, dextrose 10, CaCl2 2, buffered to a final pH of 7.4 through continuous perfusion of 95% O2-5%CO2.

Electrophysiology

Glass microelectrodes were pulled on a Flaming-Brown puller (Model P-87, Sutter Instruments, San Rafael, CA, U.S.A.) using thin walled capillaries (TW-100F, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, U.S.A.). In order to label neurons intracellularly, micropipette tips were filled with 1% biocytin in 2 M potassium acetate and backfilled with 4 M potassium acetate. Intracellular recordings from neurons in the lateral amygdala were controlled using an AxoClamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.) in bridge mode under current clamp conditions while continuously monitoring the bridge balance. Electrode resistance ranged from 60–80 MΩ. PNs with stable resting membrane potentials more negative than −60 mV, input resistances of more than 40 MΩ and overshooting action potentials were used for experiments. Membrane potential was monitored with an oscilloscope and plotted on a chart recorder. Data were digitized (NeuroCorder DR-384, Neurodata, New York, NY, U.S.A.) and stored on videotape for offline-analysis using a CED 1401 interface and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, U.K.).

To control for changes in electrode tip potential, at the end of the experiment the direct current offset of the electrode in the bathing medium was determined and the membrane potential corrected accordingly. Typically changes in electrode tip potential were below 5 mV.

Epi-illumination of the slices allowed to locate the LA and other relevant brain regions for this study, e.g. the external capsule. Electrical microstimulation (100 μs, 0.05–0.2 mA current pulses) via a bipolar tungsten electrode placed on the surface of the slice within the LA or over the external capsule evoked multiphasic postsynaptic responses. Stimulus amplitude and polarity were chosen to evoke strong PSPs without reaching spike threshold or evoking antidromic action potentials. We focused on the fast GABAA receptor-mediated IPSP that was reliably evoked during electrical stimulation. The reversal potential of the GABA-mediated response was determined by holding the neuron at different membrane potentials through injection of constant current.

Pharmacology

Pharmacologically active substances were applied by local superfusion on the exposed surface of parts of the slice containing the LA through pipettes of a larger tip diameter (10–20 μm) by constant low pressure (Picospritzer II, General Valve Corp., Fairfield, NJ, U.S.A.). Adenosine, CHA, DPCPX and GABA were locally applied to the neurons in small volumes (5–20 pl) through broken glass microelectrodes (2–5 μm tip diameter) that were either positioned on the exposed surface of the slice or lowered into the slice close to the recording site until maximal responses were elicited (Danober & Pape, 1998a). The drugs used were: adenosine (Ado), DL-(−)-2-amino-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AP-5), (−)-bicuculline methiodide (Bic), CGP 35348, N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA), 6,7-Dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX), 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). All substances were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), except for CGP 35348, which was kindly provided by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland).

Histology

Biocytin (1%) was intracellularly injected into PNs by passing depolarizing current pulses to later verify the identity and location of the stained neurons. Slices containing labelled neurons were fixed in paraformaldehyde (4%) for 24 h. Afterwards, slices were washed with PBS and incubated overnight with Cy3-Streptavidin in PBS (dilution 1 : 300) with 0.3% Triton and 2% BSA. Subsequently, slices were washed in PBS, dehydrated with ethanol, cleared in xylol and mounted with DePeX (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). The slices were visualized using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS-NT).

Analysis

Data are presented as means±s.d. and number of observations. The Wilcoxon-Test was used in statistical analysis (Bronstein & Semendjajew, 1987; Dixon & Massey, 1969). Values for individual cells were averaged from amplitudes of three subsequent IPSPs, membrane potentials or membrane resistances, respectively, before (control, normalized), during maximal responses to and following application (wash) of the drugs.

Results

Intracellular recordings were obtained from 47 neurons in the LA of the rat. These neurons had electrophysiological and morphological properties similar to those described earlier of projection neurons (Pape et al., 1998; Paré et al., 1995). The average resting membrane potential of these neurons was −69±8 mV, and the apparent input resistance was 56±16 MΩ. The neurons showed inward rectification in the depolarizing direction, action potentials overshooting 0 mV and slow oscillations (2–10 Hz) of the membrane potential at a range subthreshold to spike generation and suprathreshold, contributing to the generation of regular spike patterns in response to continued depolarizing influences. Staining of neurons with biocytin and subsequent incubation with Cy3-Streptavidin revealed spiny dendrites and cells of pyramidal- or stellate-like appearance (n=21, not shown, see Figure 6 in Danober & Pape, 1998b).

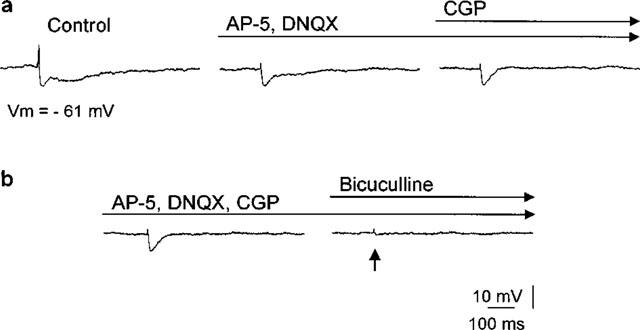

Electrical microstimulation of the external capsule or within the LA (single pulses, 100 μs duration) reproducibly gave rise to a triphasic postsynaptic reponse. An initial excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) was followed by a biphasic inhibitory PSP containing a fast and a slow component (Figure 1a) as described earlier for GABAA- and GABAB-mediated IPSPs in amygdaloid nuclei (Danober & Pape, 1998a; Nose et al., 1991; Rainnie et al., 1991a,1991b; Sugita et al., 1993; Washburn & Moises, 1992a). Here, we focused on the fast GABAA mediated IPSP. Local superfusion of the NMDA and non-NMDA antagonists (AP-5, DL-(−)-2-amino-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid, 0.5 mM; DNQX, 6,7-Dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, 0.1 mM) and a GABAB antagonist (CGP 35348, 2 mM) blocked the EPSP and slow IPSP for the duration of an experiment (>60 min). Under these conditions, the remaining fast IPSP had a reversal potential of −76 ±6 mV (n=26, not shown) and was blocked by bicuculline (bicuculline methiodide, 0.1–1 mM) (Figures 1b and 4) indicating mediation through a GABAA receptor-coupled chloride conductance as described earlier (Danober & Pape, 1998a; Nose et al., 1991; Rainnie et al., 1991a,1991b; Sugita et al., 1993; Washburn & Moises, 1992b).

Figure 1.

Typical multiphasic postsynaptic response of a projection neuron in the LA evoked by local electrical stimulation (100 μs, 0.05–0.2 mA) consists of a fast EPSP followed by a two component IPSP. (a) The fast IPSP was pharmacologically isolated by applying NMDA (AP-5, 0.5 mM) and non-NMDA (DNQX, 0.1 mM) antagonists and a GABAB antagonist (CGP, 2 mM). (b) Bicuculline (bicuculline methiodide, 1 mM) blocked the fast GABAA-mediated IPSP. The arrow indicates the time of electrical stimulation, the number indicates the prevailing membrane potential (Vm).

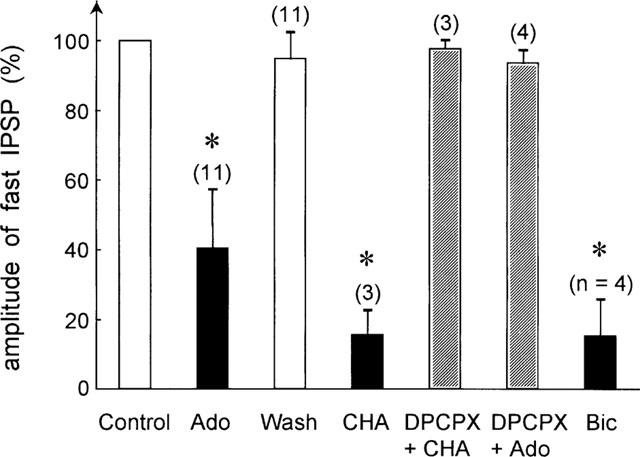

Figure 4.

Summary of the modulatory effects of various agents on the fast IPSP. The fast IPSP under control condition was set to 100% in each cell. Number of observations is indicated. *Indicates statistically significant differences (P<0.01). Application of adenosine (Ado, 100 μM) significantly reduced the IPSP amplitude. This effect was fully reversible (Wash). CHA (N6-cyclohexyladenosine, 0.1 mM) also significantly reduced the fast IPSP amplitude (P<0.05), an effect that was antagonized by DPCPX (8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine, (0.1 mM)). In the presence of DPCPX adenosine had no significant modulatory effect on the fast IPSP amplitude. Bicuculline methiodide (Bic, 1 mM) reduced the amplitude of the fast IPSP, indicating that the IPSP was a GABAA receptor-mediated conductance.

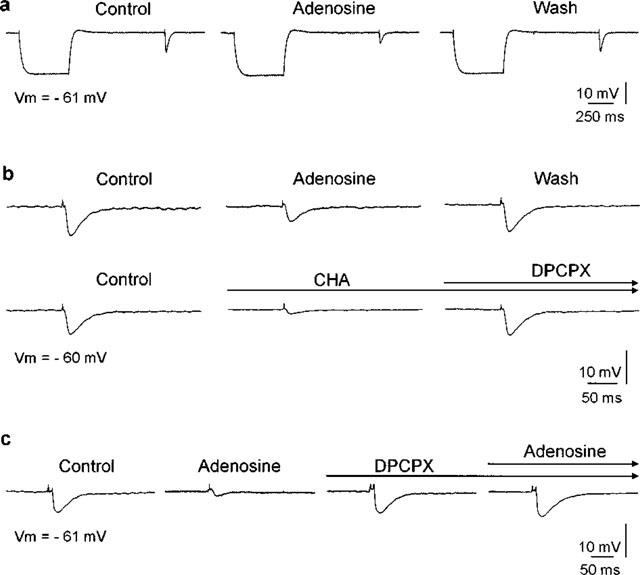

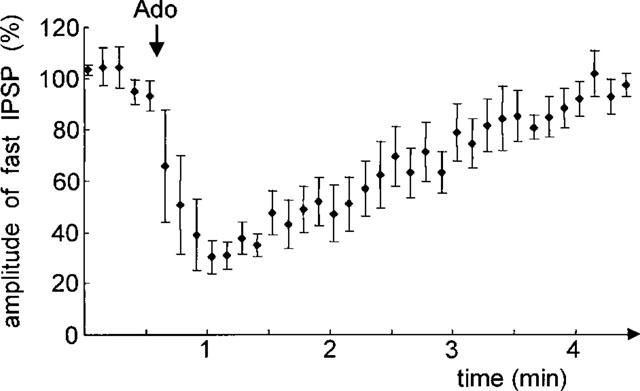

After pharmacological isolation of the fast IPSP we tested the effects of adenosine and adenosine ant-/agonists. To achieve maximal responses to adenosine, the application pipette was lowered into the slice close to the recording site (⩽50 μm distance) where adenosine was applied in different depths (50 μm steps) until maximal responses were observed. In an initial set of experiments, the maximal amplitude of adenosine action on IPSPs was determined by using adenosine at a rather high concentration (1–5 mM). In subsequent experiments the concentration of adenosine was lowered (0.1 mM) to yield maximal responses at the lowest possible concentration. Under these conditions, adenosine (0.1 mM) reversibly reduced the fast IPSP (Figure 2). The reduction started immediately (<10 s) after application of adenosine and reached a maximum within 30 s (Figure 3). Full recovery of the fast IPSP was typically achieved within 3–4 min following cessation of application. A reduction in amplitude of the fast IPSP was observed in 61% of the recorded cells (n=18). While adenosine was capable of completely suppressing the IPSP, the reduction averaged 40.3±16.9% in the sample of neurons that have been analysed in detail (n=11) (Figure 4). A reduction in responsiveness upon repetitive application was not observed, indicating a lack of desensitization.

Figure 2.

Pharmacological properties of adenosine effects. (a) Adenosine (100 μM) reduced the amplitude of the fast IPSP. Responses of a projection neuron to electrical stimulation in the lateral amygdala before (Control), during (Adenosine) and after local adenosine application (Wash). The fast IPSP was reduced in amplitude during adenosine application and regained its amplitude afterwards. A 500-ms hyperpolarizing current pulse (0.3 nA) preceded the electrical stimulation. The membrane potential and the input resistance remained constant during adenosine treatment. (b) The response to adenosine was mimicked by a selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA) (0.1 mM). The longlasting effect was reversed by application of a selective A1 receptor antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) (0.1 mM). (c) The response to adenosine was also blocked by DPCPX. Traces represent averages of three consecutive responses; membrane potential (Vm) as indicated.

Figure 3.

Time course of the action of adenosine on the fast IPSP. Amplitudes of the fast IPSP were normalized and averaged from four cells in different slices. Local application of adenosine (Ado, indicated by arrow) (0.1 mM) reduced the amplitude of the fast IPSP within seconds. The maximum effect was reached within 30 s. The fast IPSP gradually recovered (3–4 min) to its original amplitude.

The membrane resting potential did not change in response to adenosine application (Figure 2). Likewise, hyperpolarizing current pulses (0.3 nA) delivered just prior to electrical stimulation revealed no change in membrane input resistance in response to adenosine application.

The modulatory effect of adenosine was mimicked by a selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA) (0.1 mM) in all cells tested (n=3) (Figure 2b). Compared with adenosine, the effect of CHA was stronger and followed a slower time course, presumably due to physical properties of the agonist such as lipid solubility (Dunwiddie, 1985) and/or reuptake or metabolism of adenosine (Wu & Phillis, 1984). The selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) (0.1 mM) reversed the reduction of IPSP amplitude evoked by adenosine (n=4) or CHA (n=3) (Figure 2b and c). Application of DPCPX in the absence of the agonist adenosine did not result in a consistent increase of the fast IPSP (n=9, not shown).

A summary of the effects of the various pharmacological agents is shown in Figure 4. Compared to control amplitudes of the fast IPSP, adenosine significantly reduced the amplitude of the fast IPSP (n=11, P<0.01, Wilcoxon-Test). This effect was fully reversible (wash) and mimicked by the adenosine A1 receptor agonist CHA (n=3, P<0.05). The adenosine A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX reversed the effect of CHA and also blocked the effect of adenosine. Bicuculline methiodide (0.1–1 mM), a GABAA receptor antagonist also reduced the fast IPSP (n=4, P<0.05), indicating that the fast IPSP was mediated by a GABA-sensitive postsynaptic conductance.

The site of action of adenosine was primarily presynaptic as indicated by a constant membrane potential and constant membrane resistance during hyperpolarizing current pulses before and after application of adenosine (Figure 5). Further support for a presynaptic effect of adenosine comes from an experiment in which GABA (1 mM) was locally applied to the slice, first without and subseqently in the presence of adenosine (Figure 6). Under control conditions, local application of GABA close (50–100 μm) to the presumed somatic recording site evoked a biphasic response from rest, consisting of a depolarizing followed by a hyperpolarizing component, as has been observed before (Washburn & Moises, 1992b). In the presence of adenosine, PSPs in response to electrical stimulation were significantly reduced in amplitude (n=6, P<0.01). However, the response to application of GABA was not significantly different under control conditions and in the presence of adenosine with respect to the time course of the response and the amplitude of the GABA-induced hyperpolarization (n=6, P>0.05). This suggests that adenosine exerted its modulatory effect on presynaptic neurons.

Figure 5.

Lack of effect of adenosine on resting membrane potential or input resistance of the postsynaptic neuron during modulation of the fast IPSP. Vm-pre, Vm-post: resting membrane potential before and during application of adenosine in the same cell. Ri-pre, Ri-post: resting input resistance before and during application of adenosine in those cells.

Figure 6.

Lack of effect of adenosine on responses to exogenous GABA (1 mM) during modulation of PSPs. (a) The electrically evoked PSPs (100 μs, 0.1 mA stimulus) precede the GABA response and are shown at an extended time scale below. The arrows indicate the GABA application. Control – before adenosine application, Adenosine – adenosine was applied to the slice. (b) Averaged data from six cells in different slices. The response amplitude (IPSP and GABA-induced hyperpolarization, respectively) was set to 100% in each cell. *Indicates statistically significant differences (P<0.01).

It is noteworthy that the modulatory effect of adenosine was not restricted to the fast IPSP. When adenosine was applied to the slice before pharmacological isolation of the fast IPSP it reversibly reduced the amplitudes of both EPSPs as well as IPSPs (data not shown, cf. Figure 6). The time course and the extent of the reduction of the PSPs corresponded well to the effects of adenosine on the isolated fast IPSP.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that adenosine modulates inhibitory transmission between neurons in the lateral amygdala of the rat. Below, the mechanism and localization of this effect and the possible functional significance are discussed.

Mechanism of action and localization of modulatory adenosine effect

Local application of adenosine reversibly reduced the fast IPSP with a rapid time course. Typically, the onset of the adenosine effect occurred within seconds after adenosine application, reached its peak within 30 s, and was fully reversed within 4 min. Adenosine applied to the surface of the slice is likely to be rapidly metabolized (Dunwiddie, 1985; Greene & Haas, 1991) and thus has a relatively shortlasting as well as spatially restricted effect on neurotransmission. Therefore, in the present study, we applied adenosine close to the recorded neurons by lowering the application pipette into the slice. The concentration of adenosine at the site of action in the slice is difficult to ascertain since it may be altered, for instance, by uptake and ectonucleotidases (Dunwiddie, 1985; Greene & Haas, 1991). For this reason, it seems not feasible to establish dose-response relationships under the present experimental conditions.

Adenosine could have an effect either on presynaptic GABA release by interneurons and/or on postsynaptic GABA receptors of projection neurons. In the latter case, the inhibitory potential after local application of GABA should be reduced in the presence of adenosine. Such an effect of adenosine was not observed. In addition, no clear postsynaptic effects on the recorded projection neurons after adenosine application were observed with respect to membrane potential and input resistance. Thus, the modulatory effect of adenosine appears to be of presynaptic nature.

The exact site of action of adenosine on presynaptic neurons remains to be determined. Measuring miniature PSP frequency would greatly help to clarify the presynaptic site of action of adenosine. The use of intracellular ‘sharp' recording electrodes in this study did not allow the detection of miniature IPSPs at a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio and thus the determination of the effect of adenosine on spontaneous synaptic activity. Whole cell patch clamping to record spontaneous activity in the slice preparation of the lateral amygdala (personal communication by S. Meis and C. Szinyei) suggests that the frequency of such events is rather low, making it difficult to collect enough data. However, the few results available on adenosine effects on GABAergic synaptic transmission indicate a presynaptic reduction in GABA release (Chen & van den Pol, 1997; Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995) whereas direct postsynaptic responses have not been observed in identified GABAergic interneurons studied so far (Pape & McCormick, 1995). In contrast, projection neurons in the same preparation were responsive to adenosine (Pape, 1992). In summary, although direct evidence cannot be provided on the basis of the present study, it seems feasible to speculate that adenosine decreases IPSPs in projection neurons of the lateral amygdala also through reduction of GABA release from presynaptic terminals.

Two major subtypes of adenosine receptors (A1 and A2) have been described for central neurons (Fredholm & Dunwiddie, 1988; Silinsky, 1989; Williams, 1987) based on the potency of selective agonists and antagonists. Recently molecular cloning has revealed additional subtypes (Collis & Hourani, 1993; Linden et al., 1991; Olah & Stiles, 1995). Our findings are consistent with an effect of adenosine on presynaptic A1 receptors since CHA, a specific adenosine A1 receptor agonist, mimicked the modulatory effect of adenosine. Furthermore, a specific adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, DPCPX, blocked the modulatory effect and reversed the effect of CHA. Taken together, the results suggest that adenosine stimulates presynaptic A1 receptors which reduce the release of GABA from inhibitory interneurons in the lateral amygdala. Recently, several studies found an effect of adenosine through A1 receptor activation on inhibitory transmission (Chen & van den Pol, 1997; Kirk & Richardson, 1994; Nose et al., 1991; Uchimura & North, 1991; Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995) such as depression of a GABAergic synaptic conductance or reduction of inhibitory potentials. Our results are consistent with recent findings of adenosine-mediated inhibition of GABAergic transmission in several brain areas, such as thalamus (Ulrich & Huguenard, 1995), suprachiasmatic and arcuate nucleus (Chen & van den Pol, 1997), substantia nigra zona reticulata (Shen & Johnson, 1997). In contrast, A2 receptors have been found to have potentiating effects at central synapses (Sebastiao & Ribeiro, 1996; Umemiya & Berger, 1994).

Functional significance of modulatory adenosine effect

Electrical stimulation of afferents that project to the lateral amygdala evokes excitatory and inhibitory PSPs and thus results in a dual effect with direct excitation of projection neurons coupled with concurrent disynaptic feed-forward inhibition via interneurons (Rainnie et al., 1991a,1991b; Washburn & Moises, 1992a,1992b). The EPSPs are mediated by feedforward glutamate receptor-mediated excitation. The IPSPs are either polysynaptic in origin or they are monosynaptically mediated by feedforward inhibition via local GABAergic interneurons since (a) the IPSPs can be evoked after blocking excitatory transmission (this study), (b) connections between different basolateral nuclei primarily consist of excitatory connections (Smith & Paré, 1994), and (c) lesions deafferenting the basolateral complex of the amygdala lead to minor decreases in glutamic acid decarboxylase levels (Le Gal La Salle et al., 1978). Thus, the excitability of projection neurons in the lateral amygdala depends upon the relative strength of the inputs to projection neurons and interneurons.

A recent study revealed that activation of major afferent systems evokes relatively invariant synaptic responses with this type of feedforward inhibition in the lateral amygdala (Lang & Paré, 1997). Powerful IPSPs regulate the responses of projection neurons in the lateral amygdala relatively irrespective of the stimulation site, i.e., perirhinal, entorhinal, basomedial or lateral amygdala stimulation (Lang & Paré, 1997). Thus, the LA seems to be equipped with an inhibitory gating mechanism regulating information flow through the amygdala (Lang & Paré, 1998). Adenosine, in turn, may participate in these neuronal processes related to fear conditioning, learning and memory in the amygdala, e.g., by directly interacting with the inhibitory mechanisms and/or by modulating the recently shown potentiation of GABAA-mediated synaptic currents in pyramidal neurons after tetanic stimulation of inputs to interneurons (Mahanty & Sah, 1998).

Since adenosine is a product of cellular metabolism and probably released unspecifically from neurons into the surrounding neuropil in situations such as epileptic seizures (Dunwiddie, 1985; Greene & Haas, 1991), the exact role of adenosine in modulating synaptic activity under pathophysiological conditions needs further study.

Conclusions

The various modulating functions of adenosine in the brain correspond to the wide distribution of adenosine receptors throughout the brain (Dunwiddie, 1985). Here we show that adenosine significantly reduces GABA transmitter release of inhibitory neurons in the lateral amygdala. Recent evidence indicates that neuronal responsiveness in the amygdala is largely controlled by inhibitory processes which are particularly important for the prevention of epileptiform discharges (Lang & Paré, 1997). Modulation of inhibitory potentials (e.g., GABAA-mediated potentials) plays a key role for this responsiveness in the synaptic network of the amygdala. The results of the present study demonstrate a strong reduction of GABAergic influences through activation of presynaptic adenosine A1 receptors.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Sonderforschungsbereich 426 TP B3). We thank A. Reupsch, A. Ritter and R. Ziegler for expert general laboratory assistance.

Abbreviations

- Ado

adenosine

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AP-5

DL-(−)-2-amino-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- Bic

(−)-bicuculline methiodide

- CHA

N6-cyclohexyladenosine

- CNS

central nervous system

- DNQX

6,7-Dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- EPSP

excitatory postsynaptic potential

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- IPSP

inhibitory postsynaptic potential

- LA

lateral nucleus of the amygdala

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PN

projection neuron

- PSP

postsynaptic potential

References

- AGGLETON J.P. The amygdala: neurobiological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- BRONSTEIN I.N., SEMENDJAJEW K.A. Taschenbuch der Mathematik 1987Thun and Frankfurt/Main: Harri Deutsch; 688–689.23rd edn., (eds). Grosche, G., Ziegler, V. & Ziegler, D [Google Scholar]

- CHEN G., VAN DEN POL A.N. Adenosine modulation of calcium currents and presynaptic inhibition of GABA release in suprachiasmatic and arcuate nucleus neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:3035–3047. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG L.-L., WANG S.-J., GEAN P.-W. Serotonin depresses excitatory synaptic transmission and depolarization-evoked Ca2+ influx in rat basolateral amygdala via 5-HT1A receptors. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:2163–2172. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLIS M.G., HOURANI S.M. Adenosine receptor subtypes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;14:360–366. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANOBER L., PAPE H.-C. Mechanisms and functional significance of a slow inhibitory potential in neurons of the lateral amygdala. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998a;10:853–867. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANOBER L., PAPE H.-C. Strychnine-sensitive glycine responses in neurons of the lateral amygdala: an electrophysiological and immunocytochemical characterization. Neuroscience. 1998b;85:427–441. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00648-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIXON W.J., MASSEY F.J. Introduction to statistical analysis 1969New York: McGraw Hill; 3rd edn [Google Scholar]

- DRAGUNOW M. Purinergic mechanisms in epilepsy. Prog. Neurobiol. 1988;31:85–108. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(88)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNWIDDIE T.V. The physiological role of adenosine in the central nervous system. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1985;27:63–139. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRY B., MAGISTRETTI P.J., PRALONG E. Noradrenaline modulates glutamate-mediated neurotransmission in the rat basolateral amygdala in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997;9:1356–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., DUNWIDDIE T.V. How does adenosine inhibit transmitter release. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1988;9:130–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLAGHER M., CHIBA A.A. The amygdala and emotion. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996;6:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERBER U., GREENE R.W., HAAS H.L., STEVENS D.R. Characterization of inhibition mediated by adenosine in the hippocampus of the rat in vitro. J. Physiol. 1989;417:567–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLOOR P.Role of the amygdala in temporal lobe epilepsy The Amygdala: Neurobiological Aspects of Emotion, Memory and Mental Dysfunction 1992New York: Wiley-Liss; 505–538.(ed). Aggleton, J.P. [Google Scholar]

- GREENE R.W., HAAS H.L. The electrophysiology of adenosine in the mammalian central nervous system. Progr. Neurobiol. 1991;36:329–341. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90005-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEINBOCKEL T., PAPE H.-C. Modulatory effects of adenosine on postsynaptic potentials of projection neurons in the lateral amygdala of the rat. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1998a;435:R135. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEINBOCKEL T., PAPE H.-C. Influence of adenosine on inhibitory neurotransmission in the rat lateral amygdala. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998b;10:35. [Google Scholar]

- HUSTON J.P., HAAS H.L., BOIX F., PFISTER M., DECKING U., SCHRADER J., SCHWARTING R.K.W. Extracellular adenosine levels in neostriatum and hippocampus during rest and activity periods of rats. Neuroscience. 1996;73:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSEY K., MOGUL D.J. Adenosine A2-receptors modulate hippocampal synaptic transmission via a cyclic-AMP-dependent pathway. Neuroscience. 1998;84:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRK I., RICHARDSON P. Adenosine A2a receptor-mediated modulation of striatal [3H]GABA and [3H]acetylcholine release. J. Neurochem. 1994;62:960–966. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62030960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANG E.J., PARÉ D. Similar inhibitory processes dominate the responses of cat lateral amygdaloid projection neurons to their various afferents. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:341–352. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANG E.J., PARÉ D. Synaptic responsiveness of interneurons of the cat lateral amygdaloid nucleus. Neuroscience. 1998;83:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEDOUX J. Emotion: clues from the brain. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1995;46:209–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LE GAL LA SALLE G., PAXINOS G., EMSON P., BEN-ARI Y. Neurochemical mapping of GABAergic systems in the amygdaloid complex and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Brain Res. 1978;155:387–403. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDEN J., TUCKER A.L., LYNCH K.R. Molecular cloning of adenosine A1 and A2 receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991;12:326–328. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90589-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAHANTY N.K., SAH P. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors mediate long-term potentiation in interneurons in the amygdala. Nature. 1998;394:683–687. doi: 10.1038/29312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHELL J.B., LUPICA C.R., DUNWIDDIE T.V. Activity-dependent release of endogenous adenosine modulates synaptic responses in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:3439–3447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03439.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORTON R.A., DAVIES C.H. Regulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated synaptic responses by adenosine receptors in the rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 1997;502.1:75–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.075bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOSE I., HIGASHI H., INOKUCHI H., NISHI S. Synaptic responses of guinea pig and rat central amygdala neurons in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 1991;65:1227–1241. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.5.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLAH M.E., STILES G.L. Adenosine receptor subtypes: characterization and therapeutic regulation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995;35:581–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.003053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAPE H.-C. Adenosine promotes burst activity in guinea-pig geniculocortical neurones through two different ionic mechanisms. J. Physiol. 1992;447:729–753. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAPE H.-C., MCCORMICK D.A. Electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of interneurons in the cat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuroscience. 1995;68:1105–1125. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00205-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAPE H.-C., PARÉ D., DRIESANG R.B. Two types of intrinsic oscillations in neurons of the lateral and basolateral nuclei of the amygdala. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:205–216. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARÉ D., PAPE H.-C., DONG J. Bursting and oscillating neurons of the cat basolateral amygdaloid complex in vivo: electrophysiological properties and morphological features. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1–13. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.3.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PITKÄNEN A., SAVANDER V., LEDOUX J. Organization of intra-amygdaloid circuits in the rat: an emerging framework for understanding functions of the amygdala. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:517–523. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORKKA-HEISKANAN T., STRECKER R.E., THAKKAR M., BJØRKUM A.A., GREENE R.W., MCCARLEY R.W. Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science. 1997;276:1265–1268. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAINNIE D.G., ASPRODINI E.K., SHINNICK-GALLAGHER P. Excitatory transmission in the basolateral amygdala. J. Neurophysiol. 1991a;66:986–998. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.3.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAINNIE D.G., ASPRODINI E.K., SHINNICK-GALLAGHER P. Inhibitory transmission in the basolateral amygdala. J. Neurophysiol. 1991b;66:999–1009. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.3.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAINNIE D.G., GRUNZE H.C.R., MCCARLEY R. W., GREENE R.W. Adenosine inhibition of mesopontine cholinergic neurons: implications for EEG arousal. Science. 1994;263:689–692. doi: 10.1126/science.8303279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEBASTIAO A.M., RIBEIRO J.A. Adenosine A2 receptor-mediated excitatory actions on the nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 1996;48:167–189. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN K.-Z., JOHNSON S.W. Presynaptic GABAB and adenosine A1 receptor regulate synaptic transmission to rat substantia nigra reticulata neurones. J. Physiol. 1997;505.1:153–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.153bc.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILINSKY E.M. Adenosine derivatives and neuronal function. Sem. Neurosci. 1989;1:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- SMITH Y., PARÉ D. Intra-amygdaloid projections of the lateral nucleus in the cat: PHA-L anterograde labeling combined with postembedding GABA and glutamate immunocytochemistry. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;342:232–248. doi: 10.1002/cne.903420207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNYDER S.H. Adenosine as a neuromodulator. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1985;8:103–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.08.030185.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STUTZMAN G.E., MCEWEN B.S., LEDOUX J.E. Serotonin modulation of sensory inputs to the lateral amygdala: dependency on corticosterone. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:9529–9538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09529.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGITA S., TANAKA E., NORTH R.A. Membrane properties and synaptic potentials of three types of neurone in rat lateral amygdala. J. Physiol. 1993;460:705–718. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON S.M., HAAS H.L., GÄHWILER B.H. Comparison of the actions of adenosine at pre- and postsynaptic receptors in the rat hippocampus in vitro. J. Physiol. 1992;451:347–363. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UCHIMURA N., NORTH R.A. Baclofen and adenosine inhibit synaptic potentials mediated by γ-aminobutyric acid and glutamate release in rat nucleus accumbens. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;258:663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ULRICH D., HUGUENARD J.R. Purinergic inhibition of GABA and glutamate release in the thalamus: implications for thalamic network activity. Neuron. 1995;15:909–918. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UMEMIYA M., BERGER A.J. Activation of adenosine A1 and A2 receptors differentially modulates calcium channels and glycinergic synaptic transmission in rat brainstem. Neuron. 1994;13:1439–1446. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON BOHLEN UND HALBACH O., ALBRECHT D. Tracing of axonal connectivities in a combined slice preparation of rat brains – a study by rhodamine-dextran-amine-application in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1998;81:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WASHBURN M.S., MOISES H.C. Electrophysiological and morphological properties of rat basolateral amygdaloid neurons in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1992a;12:4066–4079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-04066.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WASHBURN M.S., MOISES H.C. Inhibitory responses of rat basolateral amygdaloid neurons recorded in vitro. Neuroscience. 1992b;50:811–830. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90206-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS M. Purine receptors in mammalian tissues: pharmacology and functional significance. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1987;27:315–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.27.040187.001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU P.H., PHILLIS J.W. Uptake by central nervous tissue as a mechanism for the regulation of extracellular adenosine concentrations. Neurochem. Internat. 1984;6:613–632. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(84)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]