Abstract

In the present study we investigated the role of A2A adenosine receptors in hippocampal synaptic transmission under in vitro ischaemia-like conditions.

The effects of adenosine, of the selective A2A receptor agonist, CGS 21680 (2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine), and of selective A2A receptor antagonists, ZM 241385 (4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)-{1,2,4}-triazolo{2,3-a}{1,3,5}triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol) and SCH 58261 (7-(2-phenylethyl)-5-amino-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine), have been evaluated on the depression of field e.p.s.ps induced by an in vitro ischaemic episode.

The application of 2 min of in vitro ischaemia brought about a rapid and reversible depression of field e.p.s.ps, which was completely prevented in the presence of the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX (1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine) (100 nM). On the other hand both A2A receptor antagonists, ZM 241385 and SCH 58261, by themselves did not modify the field e.p.s.ps depression induced by in vitro ischaemia.

A prolonged application of either adenosine (100 μM) or CGS 21680 (30, 100 nM) before the in vitro ischaemic episode, significantly reduced the synaptic depression. These effects were antagonized in the presence of ZM 241385 (100 nM).

SCH 58261 (1 and 50 nM) did not antagonize the effect of 30 nM CGS 21680 on the ischaemia-induced depression.

These results indicate that in the CA1 area of the hippocampus the stimulation of A2A adenosine receptors attenuates the A1-mediated depression of synaptic transmission induced by in vitro ischaemia.

Keywords: Adenosine, A2A and A1 adenosine receptors, CGS 21680, SCH 58261, ZM 241385, synaptic responses, hippocampal slices, in vitro ischaemia

Introduction

In the central nervous system (CNS), adenosine is an important neuromodulator which acts on four different receptors: A1, A2A, A2B and A3 (Fredholm et al., 1994). The well established inhibitory tonus exerted by endogenous adenosine on synaptic transmission is mainly attributed to activation of the A1 adenosine receptor type (Wu & Saggau, 1994), which is expressed with high density and widespread distribution in the brain (Fastbom et al., 1987).

After introduction of the A2A adenosine receptor agonist CGS 21680 (Hutchinson et al., 1989), several excitatory actions of A2A adenosine receptor stimulation have been described in the brain (see: Latini et al., 1996; Sebastiao & Ribeiro, 1996). In the rat brain CGS 21680 is 180 and 40 fold more selective for A2A than for A1 and A3 receptors, respectively, and virtually inactive on A2B receptors (Jarvis et al., 1989; Williams et al., 1989).

Early autoradiographic (Jarvis & Williams, 1989; Martinez-Mir et al., 1991) and molecular biology studies (Schiffmann et al., 1990; 1991; Fink et al., 1992) showed that A2A adenosine receptors were mainly confined to the striatal region. However, lower levels of expression of A2A receptor mRNA (Cunha et al., 1994; Dixon et al., 1996) and of [3H]-CGS 21680 binding sites (Wan et al., 1990; Cunha et al., 1994; Johansson & Fredholm, 1995) have also been detected in the hippocampus and cortex. Finally, a immunohistochemical analysis of A2A receptor distribution in the rat brain has recently confirmed their presence in the hippocampus and cortex (Rosin et al., 1998).

Electrophysiological investigations of the role of A2A adenosine receptors in synaptic functions have shown both an increase (Sebastiao & Ribeiro, 1992; Cunha et al., 1994; 1997; Li & Henry, 1998) and no significant effect (Dunwiddie et al., 1997; O'Kane & Stone, 1998) of A2A receptor stimulation on hippocampal neurotransmission. Although the mechanisms by which A2A receptors increase excitatory neurotransmission are not fully understood, it has been shown that CGS 21680 may decrease the ability of A1 receptor agonists to inhibit hippocampal excitatory neurotransmission (Cunha et al., 1994; O'Kane & Stone, 1998).

In the hippocampus it appears established that, under hypoxic and ischaemic conditions, a consistent increase in the extracellular concentration of endogenous adenosine (Pedata et al., 1993; Latini et al., 1998b; 1999) is associated with activation of A1 adenosine-receptors, which results in a significant depression of synaptic transmission (Fowler, 1989; 1990; Canhao et al., 1994; Lucchi et al., 1996; Latini et al., 1999). This activation of A1 receptors and the subsequent reduction in glutamate release is believed to be one of the principal neuroprotective mechanisms of adenosine against ischaemic brain damage (Rudolphi et al., 1992). On the other hand, the role of A2A adenosine receptors under brain ischaemia is still not clear (see Ongini & Schubert, 1998) and no information on their involvement in synaptic transmission during an ischaemic episode is available.

The aim of this investigation was to study whether the stimulation of A2A receptors might counteract the synaptic depression induced by an in vitro ischaemia model. The effects of adenosine and of selective compounds such as the agonist CGS 21680 and the antagonists ZM 241385 and SCH 58261, which are active on A2A adenosine receptors, were studied on the depression of field e.p.s.ps produced by in vitro ischaemia in rat hippocampal slices.

A preliminary account of these results has been previously communicated (Latini et al., 1998a).

Methods

Preparation of hippocampal slices and induction of in vitro ischaemia

Experiments were carried out on rat hippocampal slices, prepared as previously described (Corradetti et al., 1983). Charles River male Wistar rats, 150–200 g body weight, were killed by decapitation, their hippocampi rapidly removed and placed on ice-cold oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) of the following composition (mM): NaCl 124, KCL 3.33, KH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4 2, CaCl2 2, NaHCO3 25 and D-glucose 10. Slices (400 μm thick) were cut by a McIlwain tissue chopper and kept in oxygenated aCSF for at least 1 h at room temperature. A single slice was then placed on a nylon mesh, completely submerged in a small chamber and superfused with oxygenated aCSF (30–32°C) using a peristaltic pump at a constant flow rate of 2 ml min−1. In vitro ischaemia-like conditions were induced by superfusing the slice for 2 min with aCSF without glucose and gassing with nitrogen (95% N2/5% CO2). At the end of the ischaemic period, the slice was again superfused with normal oxygenated aCSF. Each slice was exposed to two periods of ischaemia-like conditions, with a time interval of 45 min. Drugs were applied before the second ischaemic episode.

Extracellular recording of synaptic transmission in hippocampal slices

Test pulses (80 μs, 0.06 Hz) were delivered through a bipolar nichrome electrode positioned in the stratum radiatum. Evoked extracellular potentials were recorded with glass microelectrodes (2–10 MΩ) filled with 3 M NaCl, placed in the CA1 region of the stratum radiatum. Responses were amplified (Neurolog NL 104, Digitimer Ltd), digitized (sample rate, 33.33 kHz), and stored on floppy disks for later analysis using pCLAMP 6 software facilities (Axon Instruments Inc.). Stimulus-response curves were obtained by gradual increases in stimulus strength. The test stimulus pulse was then adjusted to produce a field e.p.s.p. whose slope was 40–50% of the maximum and was kept constant throughout the experiment. The field e.p.s.p. amplitude was routinely measured and expressed as the percentage of the average amplitude of the potentials measured during the 10 min preceding exposure of the hippocampal slice to in vitro ischaemia. In some experiments both the amplitude and initial slope of field e.p.s.ps were quantified, but since no appreciable differences between the effect of in vitro ischaemia on both parameters were observed, usually only amplitude measurement is shown in the figures.

Statistical analysis

All numerical data are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean. Data were analysed for their statistical significance using the paired Student's t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher post hoc test.

Drugs

Adenosine was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.); CGS 21680 (2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine) and DPCPX (1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine) from Research Biochemicals International (Natik, MA, U.S.A.); ZM 241385 (4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl) - {1,2,4} - triazolo{2,3-a}{1,3,5}triazin - 5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol) from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, U.K.). SCH 58261 (7-(2-phenylethyl)-5-amino-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine) was a generous gift of Schering-Plough Research Institute (Milan, Italy). Drugs were dissolved in 100% DMSO and then diluted in distilled water to obtain a concentration of DMSO <0.05% in the final aCSF solution. The solvent concentration was kept constant throughout the experiment by adding the same per cent of DMSO to the aCSF solution without drugs.

Results

Effect of in vitro ischaemia on field e.p.s.ps in the CA1 region of hippocampal slices

We had previously observed that the application of an in vitro ischaemic insult of 5 min duration to hippocampal slices resulted in a complete and reversible depression of field e.p.s.ps (Latini et al., 1998b; 1999). In this work, we have utilized a shorter period of in vitro ischaemia (2 min) to obtain a sub-maximal depression of field e.p.s.ps and to allow detection of drug effects in either the reduction or increase in depression.

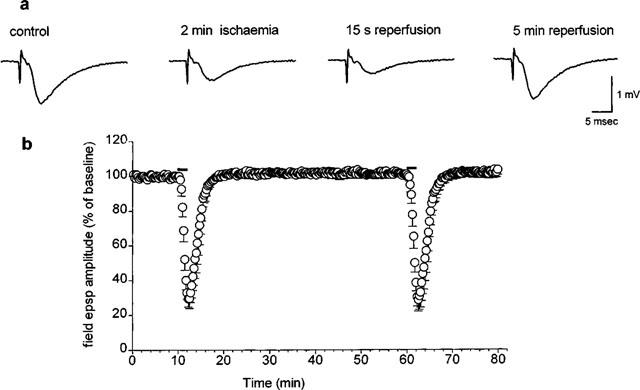

The application of an in vitro ischaemic episode of 2 min resulted in a partial and reversible depression of synaptic potentials recorded in the CA1 region. The depression of synaptic potentials started about 45 s after the beginning of the in vitro ischaemic insult, reaching a maximal inhibition of 70%, 15–30 s after reperfusion with the oxygenated aCSF solution (Figure 1). The application of a second period of 2 min of in vitro ischaemia, 45 min after the end of the first period, resulted in an identical depression of field e.p.s.p. amplitude, with the same time course. No significant differences were found by comparing synaptic potentials at any time during the first and second in vitro ischaemic periods (n=6, P>0.05). For this reason the effects of all pharmacological treatments on synaptic depression were evaluated during the second period of in vitro ischaemia in comparison with the depression induced by the first ischaemic period.

Figure 1.

Modifications in the amplitude of synaptic potentials induced by 2 min of in vitro ischaemia. (a) Traces of field e.p.s.ps recorded during a typical experiment, under control conditions, at the end of 2 min of in vitro ischaemia and after 15 s and 5 min of reperfusion. (b) Time-course of field e.p.s.p. amplitude, expressed as per cent of baseline, before, during and after the application of two consecutive in vitro ischaemic insults of 2 min (indicated by bars on graph). Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of six experiments. Absolute values (means±s.e.mean) of field e.p.s.p. amplitude in normoxic conditions (100%) were 1.06±0.04 mV before the first period of in vitro ischaemia and 1.07±0.05 mV before the second.

Effect of A1 adenosine receptor antagonist on synaptic depression induced by in vitro ischaemia

During the ischaemic episode the depression of field e.p.s.ps is mostly ascribed to A1 receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release exerted by the large amounts of adenosine flowing out of cells. Therefore the ability of the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX to block the ischaemic depression of field e.p.s.ps was assessed in our experimental conditions.

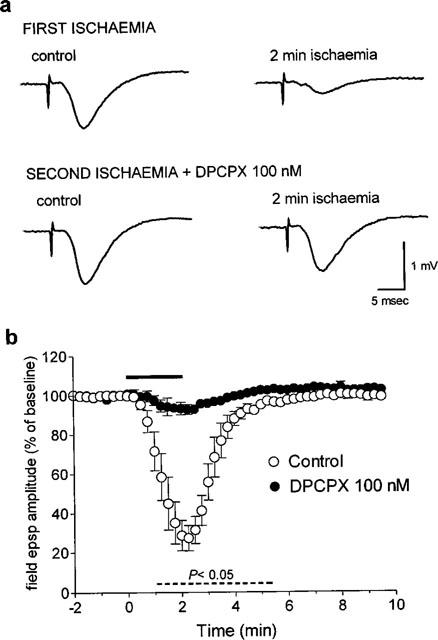

Perfusion of slices for 20 min with 100 nM DPCPX, before application of the second ischaemic insult, brought about a 10 and 12% (n=3, P<0.05, Student t-test) increase in field e.p.s.p. amplitude and slope, respectively. This confirmed an effective antagonism of A1 receptor-mediated inhibition of field e.p.s.ps caused by endogenous adenosine under normoxic conditions (Dunwiddie & Diao, 1994).

As shown in Figure 2, 100 nM DPCPX almost completely prevented the synaptic depression induced by 2 min of in vitro ischaemia. The effect of DPCPX was statistically significant at all recording times (P<0.05, paired Student's t-test) between 1 min after the beginning of the ischaemic insult up to 3.5 min of reperfusion.

Figure 2.

Effect of the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX, on the field e.p.s.p. depression induced by 2 min of in vitro ischaemia. (a) Traces of field e.p.s.ps recorded during a typical experiment, under control conditions and at the end of 2 min of in vitro ischaemia both in the absence and in the presence of DPCPX. (b) Time-course of field e.p.s.p. amplitude modifications during the first and second ischaemic episodes. Field e.p.s.p. amplitude is expressed as the percentage of averaged potentials recorded before the respective ischaemic periods. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of three experiments. Absolute values (means±s.e.mean) of field e.p.s.p. amplitude in normoxic conditions (100%) were 0.92±0.06 mV before the first period of in vitro ischaemia and 1.01±0.07 mV (+10%, P<0.05) before the second, in the presence of DPCPX. The dotted line under the graph indicates the statistical significance of the effect of DPCPX, evaluated with the paired Students t-test at each time.

A2A adenosine receptor antagonists do not affect field e.p.s.ps under normoxic conditions and during in vitro ischaemia

We have previously observed that at the end of 2 min of in vitro ischaemia, the adenosine concentration at the receptor level increases about 25 fold, starting from a basal value of 180–240 nM under normoxic conditions, and reaching an estimated value of 5 μM after the ischaemic insult (Latini et al., 1999). Considering the affinity of each adenosine receptor subtype for the endogenous ligand (1–30 nM for A1 and A2A receptors and >1 μM for A2B and A3 receptors) (Fredholm et al., 1994), it is conceivable that under these conditions all adenosine receptor subtypes could be stimulated by endogenous adenosine flowing out of cells during the ischaemic episode.

The question therefore arises as to whether, during the ischaemic period, A2A adenosine receptors are also stimulated and partially counteract the depressant effects exerted by A1 receptor stimulation. To test this possibility we evaluated the effects of two selective A2A receptor antagonists, ZM 241385 and SCH 58261, under normoxic and ischaemic conditions. It was expected that, if A2A receptors were stimulated during the ischaemic insult, their antagonism would have unmasked a greater depression during ischaemia.

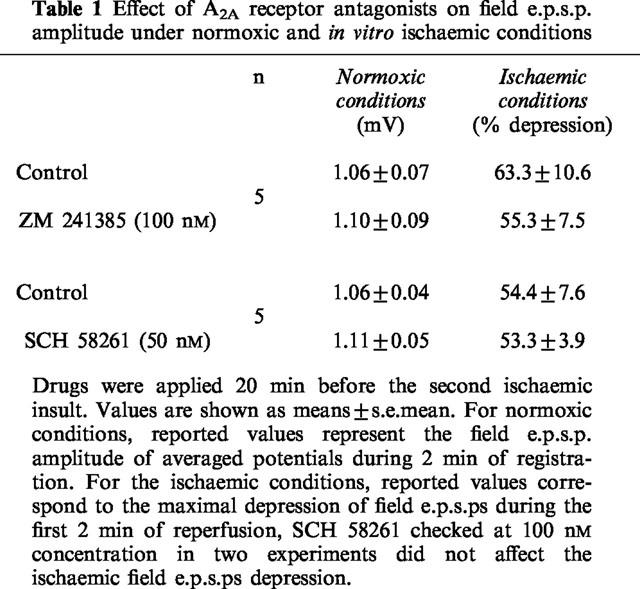

As shown in Table 1, ZM 241385 (100 nM) and SCH 58261 (50 nM) did not significantly modify either the excitatory neurotransmission under normoxic conditions or the maximal ischaemic depression of field e.p.s.p. amplitude observed during ischaemia.

Table 1.

Effect of A2A receptor antagonists on field e.p.s.p. amplitude under normoxic and in vitro ischaemic conditions

Effects of prolonged application of adenosine on ischaemia-induced depression of field e.p.s.ps

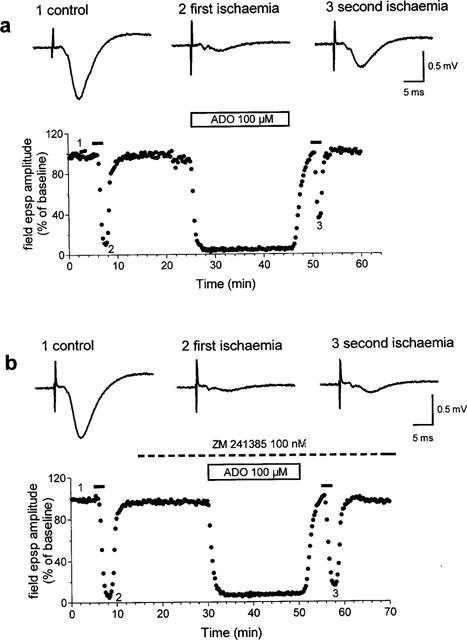

In spite of the negative results obtained using A2A selective antagonists, the possibility that A2A receptor stimulation could modulate the depression caused by ischaemia could not be discarded. A slow-time course of excitatory responses induced by CGS 21680 and exogenous adenosine is observed in the hippocampus (Li & Henry, 1998) and our previous findings demonstrated that, using longer (5 min) ischaemic episodes, the second episode recovered more rapidly from depression than the first (Latini et al., 1999). These findings suggest that periods of in vitro ischaemia longer than 2 min may be necessary to activate A2A receptors. Unfortunately a 5-min in vitro ischaemia produces a complete disappearance of field e.p.s.ps (Latini et al., 1999), likely due to supra-maximal stimulation of A1 receptors. This makes it unlikely to detect any possible effect of A2A receptor antagonists. We therefore devised a different approach to stimulate A2A receptors. Thus hippocampal slices were exposed for 20 min to a concentration of adenosine (100 μM) which should be high enough to stimulate all adenosine receptor subtypes, even in the presence of adenosine re-uptake and degradation.

As shown in one typical experiment out of four (Figure 3a), the application of 100 μM adenosine, after recovery from the first ischaemic period, resulted in a complete depression of field e.p.s.ps, followed by a rapid recovery after adenosine washout. The application of the second ischaemic insult, immediately after the complete recovery of field e.p.s.p. amplitude, resulted in a significant reduction in field e.p.s.p. depression in comparison with the first ischaemic episode. The peak depression (i.e. during the first min of reperfusion) of the field e.p.s.p. for the first ischaemic period was 84.6±0.6%, and for the second ischaemic period 39.7±4.7%, with a significant reduction of 53±5.6% (P<0.0001, n=4, ANOVA).

Figure 3.

Effect of a prolonged application of adenosine on field e.p.s.p. depression induced by in vitro ischaemia. (a) Time-course of changes in field e.p.s.p. amplitude elicited by application of adenosine (100 μM) in one typical of four experiments. Traces show field e.p.s.ps recorded at the time indicated by numbers in the graph. Adenosine was applied 15 min after the recovery of field e.p.s.p. amplitude from the first ischaemic insult, and was maintained for 20 min. The second ischaemic episode was applied immediately after recovery from adenosine effect. (b) Time-course of changes in field e.p.s.p. amplitude elicited by application of adenosine (100 μM) in the presence of the A2A adenosine receptor antagonist, ZM 241385 in one typical of four experiments. Traces show field e.p.s.ps recorded at the time indicated by numbers in the graph. ZM 241385 (100 nM) was applied 15 min before adenosine and was maintained during the second ischaemic episode and until the end of the experiment. (a) and (b) are from different slices.

As shown in Figure 3b, the attenuation of field e.p.s.p. ischaemic depression induced by the prolonged application of adenosine is significantly smaller when adenosine is applied in the presence of the A2A selective antagonist ZM 241385 (100 nM). Under these conditions the peak depression (i.e. during the first min of reperfusion) of the field e.p.s.ps during the second ischaemic period (62.8±10.6%) was not statistically different from that of the first ischaemic period (81.4±6.3%). On the other hand, the reduction in ischaemic depression (24±7.2%) was significantly different (P<0.005, Students t-test) from that caused by adenosine in the absence of ZM 241385. These results strongly support the notion that a prolonged activation (>2 min) of A2A receptors is needed to counteract the A1 mediated effects of field e.p.s.ps.

Effect of the A2A adenosine receptor agonist CGS 21680 on synaptic depression induced by in vitro ischaemia

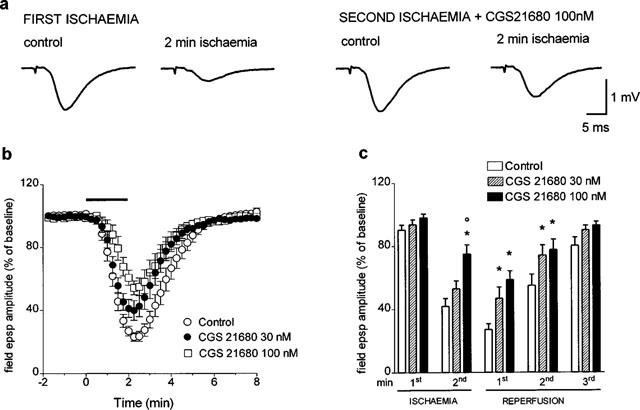

In order to confirm the involvement of A2A adenosine receptors in the attenuation of field e.p.s.p. ischaemic depression observed after the prolonged application of adenosine, we have evaluated the effect of the selective A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680. Consistent with the findings obtained with adenosine, the application of CGS 21680, 20 min before the second in vitro ischaemic insult, resulted in a significant reduction in field e.p.s.p. ischaemic depression. As shown in Figure 4a, 100 nM CGS 21680 did not affect field e.p.s.p. amplitude under normoxic conditions (absolute values of field e.p.s.p. amplitude were 1.28±0.08 mV before and 1.27±0.1 mV after the application of 100 nM CGS 21680, n=5) but partially reversed the depression of field e.p.s.p. recorded at the end of the ischaemic period. The effects of two concentrations of CGS 21680 (30 and 100 nM) and the time-course of ischaemic depression are shown in Figure 4b. Statistically significant differences between the ischaemic depression in the absence and in the presence of CGS 21680 were found during the second minute of in vitro ischaemia and during the first and second minute of reperfusion (Figure 4c). The maximal depression of field e.p.s.p. amplitude (i.e. during the first minute of reperfusion) was 29±5.4% and 43±4.5% smaller in the presence of 30 and 100 nM CGS 21680, respectively, than without drug application.

Figure 4.

Effect of the selective A2A receptor agonist, CGS 21680, on the field e.p.s.p. depression induced by 2 min of in vitro ischaemia. CGS 21680 was applied 20 min before the second ischaemic period and maintained until the end of the experiment. (a) Traces of field e.p.s.ps recorded during a typical experiment, under normoxic and ischaemic conditions, either in the absence or presence of 100 nM CGS 21680. (b) Time course of field e.p.s.p. amplitude modifications and effect of two concentrations of CGS 21680 (30 and 100 nM). Field e.p.s.p. amplitude is expressed as the percentage of averaged potentials recorded before the respective ischaemic periods. Since no significant differences were found between the first ischaemic depression in the group of experiments with 30 nM and in the group with 100 nM CGS 21680, the values from these groups are shown in the figure averaged and compared with those obtained during the second ischaemic depression in the presence of CGS 21680. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of 12 experiments for control, seven experiments for 30 nM CGS 21680 and five experiments for 100 nM CGS 21680. (c) Each bar represents the average amplitude of four consecutive field e.p.s.ps (1 min), recorded during the first and second minute of in vitro ischaemia and during the first, second and third minute of reperfusion (expressed as per cent of controls). Differences among data were analysed by ANOVA (P<0.001) followed by post hoc Fisher's test: *P<0.05 vs control, °P<0.05 vs 30 nM CGS 21680.

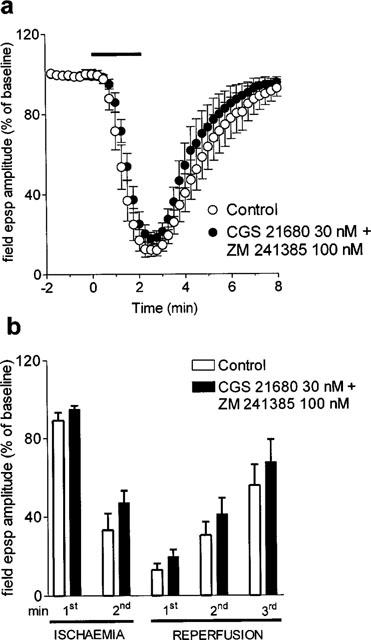

The effect of 30 nM CGS 21680 on the in vitro ischaemic-depression was antagonized by the selective A2A receptor antagonist, ZM 241385, at the concentration of 100 nM (Figure 5a). As shown in Figure 5b, no significant effect of CGS 21680 was observed in the presence of ZM 241385, both during and after the in vitro ischaemic insult.

Figure 5.

Effect of the A2A adenosine receptor antagonist ZM 241385 on the CGS 21680-induced reduction of in vitro ischaemic depression. (a) 100 nM ZM 241385 was applied 20 min before 30 nM CGS 21680 and maintained during the second period of in vitro ischaemia and until the end of the experiment. Field e.p.s.p. amplitude is expressed as the percentage of averaged potentials recorded before the respective ischaemic periods. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of five experiments. Averaged (means±s.e.mean) field e.p.s.p. amplitudes in normoxic conditions (100%) were: 1.13±0.06 before the first period of ischaemia and 1.18±0.06 before the second, in the presence of drugs. (b) Each bar represents the average amplitude of four consecutive field e.p.s.ps recorded during the first and second minute of in vitro ischaemia and during the first, second and third minute of reperfusion. No statistically significant differences among data were observed by the application of ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher's test.

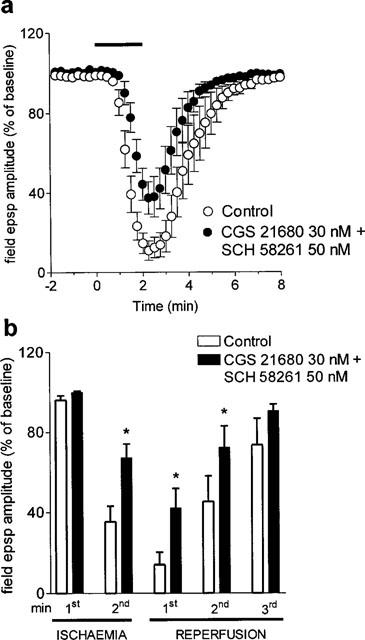

On the other hand, the application of 1 nM (n=4, data not shown) and 50 nM (n=5, Figure 6) SCH 58261, did not antagonize the effect of 30 nM CGS 21680 during and after the in vitro ischaemic insult. As shown in Figure 6b, at peak depression of field e.p.s.p. amplitude (i.e. during the first min of reperfusion), there was a 34±7.6% reduction (P<0.05, ANOVA) in synaptic depression in the presence of both SCH 58261 and CGS 21680, in comparison to control.

Figure 6.

Effect of the A2A adenosine receptor antagonist SCH 58261 on the CGS 21680-induced reduction in in vitro ischaemic depression. (a) 50 nM SCH 58261 was applied 20 min before 30 nM CGS 21680 and maintained during the second period of in vitro ischaemia and until the end of the experiment. Field e.p.s.p. amplitude is expressed as the percentage of averaged potentials recorded before the respective ischaemic periods. Each value represents the mean±s.e.mean of five experiments. Averaged (means±s.e.mean) field e.p.s.p. amplitudes in normoxic conditions (100%) were: 0.98±0.02 mV before the first period of in vitro ischaemia and 1.02±0.03 before the second, in the presence of drugs. (b) Each bar represents the average amplitude of four consecutive field e.p.s.ps recorded during the first and second minute of in vitro ischaemia and during the first, second and third minute of reperfusion. Differences among data were analysed by ANOVA (P<0.001) followed by post hoc Fisher's test: *P<0.05 vs control.

Discussion

In this study we show that the synaptic depression observed in the CA1 area under in vitro ischaemic conditions is reduced by prolonged stimulation of A2A adenosine receptors.

In our experiments the application of a short in vitro ischaemic insult (2 min) caused a submaximal and repeatable depression of field e.p.s.ps amplitude. As previously shown in the hippocampus, the induction of in vitro ischaemic conditions is associated with an increase in the extracellular concentration of adenosine (Lloyd et al., 1993; Pedata et al., 1993; Latini et al., 1995; 1999) and with depression of synaptic responses (Fredholm et al., 1984; Fowler 1989; 1990; Gribkoff et al., 1990; Pedata et al., 1993). In the CA1 area the two phenomena are temporally correlated (Latini et al., 1998b). The adenosine-mediated depression of field e.p.s.ps is mainly attributed to a decrease in glutamate release by activation of presynaptic adenosine A1 receptors (Corradetti et al., 1984; Latini et al., 1999). Our findings that the selective A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX prevents the synaptic depression induced by in vitro ischaemia, confirms the preponderant role of A1 receptors in inhibiting synaptic responses in the present experimental conditions.

In a previous work (Latini et al., 1999) we estimated that the concentration of adenosine reaching the receptor level at the second min of ischaemia was 5 μM, a concentration well above that needed to stimulate A2A receptors (see Fredholm et al., 1994). This raised the possibility that, during the ischaemic episode A2A receptors were also stimulated and acted by limiting the depression of field e.p.s.ps produced by A1 receptor activation. In our experimental conditions the effects of the two brief (2 min) ischaemic episodes on field e.p.s.ps were submaximal and superimposable in amplitude and time-course. This indicated that the first episode did not produce lasting modifications in excitatory neurotransmission sensitivity to the action of adenosine released by the second episode. The application of the A2A selective antagonist ZM 243985 between the two ischaemic episodes neither affected by itself the baseline neurotransmission nor increased the ischaemic synaptic depression. This demonstrates the absence of a detectable stimulation of A2A receptors by endogenous adenosine in normoxic conditions and by that released during the 2 min ischaemic period.

On the other hand, during ischaemic insults in vivo the levels of adenosine might rise for longer than 2 min, and the more persistent resulting activation of A2A receptors could lead to detectable effects on the outcome of the ischaemia as revealed by the hippocampal neuroprotection exerted by A2A antagonists in cerebral damage induced by global ischaemia (see: Von Lubitz 1999).

In our conditions, a 5 min episode of ischaemia speeded up the recovery time-course from a subsequent similar ischaemic episode (Latini et al., 1999). Unfortunately, this ‘pre-conditioning' effect was too small to be investigated pharmacologically, and periods of ischaemia longer than 5 min will result in the death of the preparation (Pedata et al., 1993). However, when the action of adenosine released during a longer ischaemic episode was mimicked by the application of exogenous adenosine, a significant reduction (53%) in field e.p.s.p. depression by a 2 min ischaemic episode became apparent. The fact that ZM 243985 substantially prevented the effect of adenosine on the response to ischaemia, strongly suggests that the action of adenosine was through A2A receptor stimulation and not to be ascribed to changes in adenosine re-uptake kinetics or in cell metabolism. This notion is confirmed by the similar action of the A2A selective agonist CGS 21680, which is unlikely to modify adenosine re-uptake and cell metabolism and whose effect is fully prevented by the A2A receptor antagonist ZM 243985. The residual attenuation of peak depression by adenosine (24%), observed when A2A receptors are blocked, may be attributed to other mechanisms, including a desensitization of A1 receptors elicited by activation of A3 receptors (Dunwiddie et al., 1997).

The mechanism by which A2A adenosine receptors counteract the A1 receptor-mediated effects of adenosine are at present elusive.

CGS 21680 has been shown to increase the release of excitatory neurotransmitters like acetylcholine (Cunha et al., 1995) and excitatory amino acids (Popoli et al., 1995). A facilitation of glutamate release could thus counteract the A1-mediated synaptic depression during in vitro ischaemia. This possibility is strengthened by the demonstration that CGS 21680 increases the cortical release of glutamate evoked by in vivo ischaemia (O'Regan et al., 1992).

The finding that CGS 21680 is able to decrease the synaptic depression produced by in vitro ischaemia is in agreement with previous observations showing that, under normoxic conditions, inhibition of population spike amplitude induced by the selective A1 receptor agonist, N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), is attenuated in the presence of CGS 21680 (Cunha et al., 1994; O'Kane & Stone, 1998). A reduced sensitivity of A1 receptors to adenosine has therefore been proposed as a mechanism explaining the decrease in A1 receptor-mediated responses also in the CA1 region (O'Kane & Stone, 1998).

The fact that a prolonged (>2 min) stimulation of A2A receptors is required to produce detectable effects on excitatory neurotransmission suggests the need for a persistent intracellular signalling which eventually leads to a decrease in sensitivity of A1 receptors to adenosine. In rat striatal synaptosomes, A2A receptor activation by CGS 21680 reduces the affinity of the A1 receptor for its agonists, via a cytoplasmic pathway involving the action of a protein kinase C (Dixon et al., 1997). The reasons why activation of A2A receptors for less than 2 min is unable to develop the suggested A2A/A1 receptor interactions remains unclear and requires further investigation. Nevertheless, at least two possibilities can be envisaged to explain the need for long activation of adenosine receptors to develop the effect: (1) a persistent stimulation is required to trigger the intracellular response. This might be due to the relatively low density of hippocampal A2A receptors (Dixon et al., 1996) and/or to slow production kinetics of ternary complexes with G-proteins (Kenakin, 1993; 1997). The result will be a slow accumulation of intracellular messenger(s) which might require reaching a ‘threshold' level to start the machinery responsible for A1 receptor desensitisation. (2) Once triggered, if the target of the intracellular signal is the activated conformation of A1 receptors, the machinery might require sustained stimulation of A1 receptors to be fully effective. It deserves mention also that A3 receptor stimulation needs to be maximal and prolonged to produce a delayed desensitization of A1 receptors (Dunwiddie et al., 1997).

In our experiments the effect of CGS 21680 in reducing ischaemic depression is completely prevented by ZM 241385, which is selective for A2A vs A1 (500–1000 fold) and A2A vs A2B (80 fold), but does not bind to A3 receptors (Poucher et al., 1995). ZM 241385 has been shown to displace with similar potency both striatal (Ki=0.35 nM) and hippocampal (Ki=0.52 nM) [3H]-CGS 21680 binding sites in the rat (Cunha et al., 1997) and to antagonize the effects of CGS 21680 on the depression of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus induced by N6-cyclopentyladenosine (O'Kane & Stone, 1998). In contrast the effect of CGS 21680 was not antagonized by the selective A2A receptor antagonist, SCH 58261 (Ki=2.3 nM, in the rat striatum), which is 50 fold A2A/A1 selective and does not bind to A2B and A3 receptors (Zocchi et al., 1996). SCH 58261 has been shown to discriminate between the two different binding sites observed in the rat brain for [3H]-CGS 21680 (James et al., 1992; Johansson et al., 1993; Cunha et al., 1996). Thus, SCH 58261 is able to displace the binding of [3H]-CGS 21680 from striatal membranes, but is virtually ineffective in hippocampal and cortical membranes with an estimated Ki greater than 1 μM (Lindström et al., 1996). Our finding that ZM 241385, but not SCH 58261, is able to antagonize the CGS 21680 effect is in agreement with these previous studies and suggests that the CGS 21680 effect in the hippocampus is mainly mediated by receptors different from the A2A receptor population predominant in the striatum.

One conclusion of our work is that stimulation of A2A receptors for longer than 2 min is required to detectably modify the responsiveness of excitatory neurotransmission to ischaemia. Our results therefore suggest that, after prolonged stimulation by adenosine, the effect of A2A receptor stimulation becomes detectable and net excitatory synaptic activity may be the result of decreased adenosine A1-mediated inhibitory action and of A2A-mediated stimulatory effects.

This mechanism may be of relevance in pathological conditions since, during in vivo ischaemic episodes, adenosine levels rise considerably and A2A receptors attenuate the inhibitory and neuroprotective effect elicited by A1 receptor stimulation. In accordance it has been shown that A2A receptor antagonists administered systemically (Gao & Phillis, 1994; Phillis, 1995; Von Lubitz et al., 1995; Bona et al., 1997; Jones et al., 1998b; Monopoli et al., 1998) or injected locally in the hippocampus (Jones et al., 1998a) show neuroprotective effects in in vivo models of brain ischaemia or kainate-induced excitotoxicity. Although interpretation of our in vitro experiments should be conservatively limited to the demonstration of an increase in excitatory neurotransmission by A2A receptors, it is conceivable that blockade of this effect concurs with the neuroprotective action of A2A antagonists. It is worth mentioning that the protective effects of A2A receptor blockade observed in vivo might comprise additional mechanisms unrelated to glutamate release and/or depression of synaptic activity (see Ongini & Schubert, 1998).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that, in the CA1 area of the hippocampus, stimulation of A2A receptors attenuates the depression of excitatory neurotransmission induced by adenosine through A1 receptor activation during in vitro ischaemia. This finding supports the notion that blockade of the negative interaction between A2A and A1 adenosine receptors may represent a possible mechanism of protection against ischaemic neuronal damage.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Ongini (Schering-Plough Research Institute) for the generous gift of SCH 58261. This investigation was supported by grants from the University of Florence, and was carried out within the National Research Program on Drugs (II) supported by the Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica.

Abbreviations

- aCSF

artificial cerebral spinal fluid

- ADO

adenosine

- CGS 21680

(2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- field e.p.s.p.

field excitatory post synaptic potential

- SCH 58261

7-(2-phenylethyl)-5-amino-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine

- ZM 241385

4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)-{1,2,4}-triazolo{2,3-a}{1,3,5}triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol

References

- BONA E., ADEN U., GILLAND E., FREDHOLM B.B., HAGBERG H. Neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia: the effect of adenosine receptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1327–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANHAO P., DE MENDONÇA A., RIBEIRO J.A. 1,3-Dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine attenuates the NMDA response to hypoxia in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1994;661:265–273. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORRADETTI R., LO CONTE G., MORONI F., PASSANI M.B., PEPEU G. Adenosine decreases aspartate and glutamate release from rat hippocampal slices. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1984;104:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORRADETTI R., MONETI G., MORONI F., PEPEU G., WIERASZKO A. Electrical stimulation of the stratum radiatum increases the release and neosynthesis of aspartate, glutamate, and γ-aminobutyric acid in rat hippocampal slices. J. Neurochem. 1983;41:1518–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNHA R.A., CONSTANTINO M.D., RIBEIRO J.A. ZM241385 is an antagonist of the facilitatory responses produced by the A2A adenosine receptor agonists CGS21680 and HENECA in the rat hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1279–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNHA R.A., JOHANSSON B., CONSTANTINI M.D., SEBASTIÃO A.M., FREDHOLM B.B. Evidence for high-affinity binding sites for the adenosine A2A receptor agonist [3H]CGS 21680 in the rat hippocampus and cerebral cortex that are different from striatal A2A receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353:261–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00168627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNHA R.A., JOHANSSON B., FREDHOLM B.B., RIBEIRO J.A., SEBASTIÃO A.M. Adenosine A2a receptors stimulate acetylcholine release from nerve terminals of the rat hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;196:41–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11833-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNHA R.A., JOHANSSON B., VAN DER PLOEG I., SEBASTIÃO A.M., RIBEIRO J.A., FREDHOLM B.B. Evidence for functionally important adenosine A2a receptors in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1994;649:208–216. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIXON A.K., GUBITZ A.K., SIRINATHSINGHJI D.J.S., RICHARDSON P.J., FREEMAN T.C. Tissue distribution of adenosine receptor mRNAs in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1461–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIXON A.K., WIDDOWSON L., RICHARDSON P.J. Desensitisation of the adenosine A1 receptor by the A2A receptor in the rat striatum. J. Neurochem. 1997;69:315–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNWIDDIE T.V., DIAO L. Extracellular adenosine concentrations in hippocampal brain slices and the tonic inhibitory modulation of evoked excitatory responses. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:537–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNWIDDIE T.V., DIAO L., KIM H.O., JIANG J.-L., JACOBSON K.A. Activation of hippocampal adenosine A3 receptors produces a desensitization of A1 receptor-mediated responses in rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:607–614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00607.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FASTBOM J., PAZOS A., PALACIOS J.M. The distribution of adenosine A1 receptors and 5′-nucleotidase in the brain of some commonly used experimental animals. Neuroscience. 1987;22:813–826. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)92961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINK J.S., WEAVER D.R., RIVKEES S.A., PETERFREUND R.A., POLLACK A.E., ADLER E.M, REPPERT S.M. Molecular cloning of the rat A2 adenosine receptor; selective co-expression with D2 dopamine receptors in the rat striatum. Molec. Brain Res. 1992;14:186–195. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOWLER J.C. Adenosine antagonists delay hypoxia-induced depression of neuronal activity in hipoocampal brain slice. Brain Res. 1989;490:378–384. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOWLER J.C. Adenosine antagonists alter the synaptic response to in vitro ischemia in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1990;509:331–334. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., ABBRACCHIO M.P., BURNSTOCK G., DALY J.W., HARDEN T.K., JACOBSON K.A., LEFF P., WILLIAMS M. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., DUNWIDDIE T.D., BERGMAN B., LINDSTRÖM K. Levels of adenosine and adenine nucleotides in slices of rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1984;295:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90823-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO Y., PHILLIS J.W.CGS 15943, an adenosine A2 receptor antagonist, reduces cerebral ischemia injury in the mongolian gerbil Life Sci. 19945561–65.PL [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIBKOFF V.K., BAUMAN L.A., VANDERMAELEN C.P. The adenosine antagonist 8-cyclopentyltheophilline reduces the depression of hippocampal neuronal responses during hypoxia. Brain Res. 1990;512:353–357. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90648-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUTCHINSON A.J., WEBB R.L., OEI H.H., GHAI G.R., ZIMMERMAN M.B., WILLIAMS M. CGS 21680C, an A2 selective adenosine receptor agonist with preferential hypotensive activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAMES S., XUEREB J.H., ASKALAN R., RICHARDSON P.J. Adenosine receptors in post-mortem human brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARVIS M.F., SCHULZ R., HUTCHISON A.J., DO U.H., SILLS M.A., WILLIAMS M. [3H] CGS21680, a selective A2 adenosine receptor agonist directly labels A2 receptors in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARVIS M.F., WILLIAMS M. Direct autoradiographic localization of adenosine A2 receptors in the rat brain using the A2-selective agonist, [3H]CGS 21680. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;168:243–246. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHANSSON B., FREDHOLM B.B. Further characterization of the binding of the adenosine receptor agonist [3H]CGS 21680 to rat brain using autoradiography. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:393–403. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00009-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHANSSON B., GEORGIER V., PARKINSON F.E., FREDHOLM B.B. The binding of the adenosine A2 receptor selective agonist [3H]CGS 21680 to rat cortex differs from its binding to rat striatum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;247:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90066-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES P.A., SMITH R.A., STONE T.W. Protection against hippocampal kainate excitotoxicity by intracerebral administration of an adenosine A2A receptor antagonist. Brain Res. 1998a;800:328–335. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES P.A., SMITH R.A., STONE T.W. Protection against kainate-induced excitotoxicity by adenosine A2A receptor agonists and antagonists. Neuroscience. 1998b;85:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00613-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENAKIN T.Stimulus-response mechanisms Pharmacologic analysis of drug-receptor interaction 1993Raven Press: New York; 39–68.In: Kenakin, T. (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- KENAKIN T.Drug response systems Pharmacologic analysis of drug-receptor interaction 1997Lippencott-Raven: Philadelphia; 106–144.Kenakin, T. (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- LATINI S., BORDONI F., CORRADETTI R., PEPEU G., PEDATA F. The A2A adenosine receptor agonist CGS 21680 reduces the synaptic depression induced by in vitro ischemia in rat hippocampal slices. Drug Dev. Res. 1998a;43:213. [Google Scholar]

- LATINI S., BORDONI F., CORRADETTI R., PEPEU G., PEDATA F. Temporal correlation between adenosine outflow and synaptic potential inhibition in rat hippocampal slices during ischemia-like conditions. Brain Res. 1998b;794:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LATINI S., BORDONI F., PEDATA F., CORRADETTI R. Extracellular adenosine concentrations during in vitro ischaemia in rat hippocampal slices. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:729–739. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LATINI S., CORSI C., PEDATA F., PEPEU G. The source of brain adenosine outflow during ischemia and electrical stimulation. Neurochem. Int. 1995;27:239–244. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(95)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LATINI S., PAZZAGLI M., PEPEU G., PEDATA F. A2 adenosine receptors: their presence and neuromodulatory role in the central nervous system. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996;27:925–933. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(96)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI H., HENRY J.L. Adenosine A2 receptor mediation of pre- and postsynaptic excitatory effects of adenosine in rat hippocampus in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;347:173–182. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDSTRÖM K., ONGINI E., FREDHOLM B.B. The selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist SCH 58261 discriminates between two different binding sites for [3H]-CGS 21680 in the rat brain. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;354:539–541. doi: 10.1007/BF00168448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LLOYD H.G.E., LINDSTRÖM K., FREDHOLM B.B. Intracellular formation and release of adenosine from rat hippocampal slices evoked by electrical stimulation or energy depletion. Neurochem. Int. 1993;23:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(93)90095-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUCCHI R., LATINI S., DE MENDONÇA A., SEBASTIÃO A.M., RIBEIRO J.A. Adenosine by activating A1 receptors prevents GABAA-mediated actions during hypoxia in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1996;732:261–266. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00748-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINEZ-MIR M.I., PROBST A., PALACIOS J.M. Adenosine A2 receptors: selective localization in the human basal ganglia and alterations with disease. Neuroscience. 1991;42:697–706. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90038-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONOPOLI A., LOZZA G., FORLANI A., MATTAVELLI A., ONGINI E. Blockade of adenosine A2A receptors by SCH 58261 results in neuroprotective effects in cerebral ischaemia in rats. NeuroReport. 1998;9:3955–3959. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'KANE E.M., STONE T.W. Interaction between adenosine A1 and A2 receptor-mediated responses in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;362:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONGINI E., SCHUBERT P. Neuroprotection induced by stimulating A1 or blocking A2A adenosine receptors: an apparent paradox. Drug Dev. Res. 1998;45:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- O'REGAN M.H., SIMPSON L.M., PERKINS L.M., PHILLIS J.W. The selective A2 adenosine receptor agonist CGS 21680 enhances excitatory transmitter amino acid release from the ischemic rat cerebral cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;138:169–172. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90498-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEDATA F., LATINI S., PUGLIESE A.M., PEPEU G. Investigations into the adenosine outflow from hippocampal slices evoked by ischemic-like conditions. J. Neurochem. 1993;61:284–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHILLIS J.W. The effects of selective A1 and A2 adenosine receptor antagonists on cerebral ischemic injury in the gerbil. Brain Res. 1995;705:79–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POPOLI P., BETTO P., REGGIO R., RICCIARELLO G. Adenosine A2A receptor stimulation enhances striatal extracellular glutamate levels in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;287:215–217. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POUCHER S.M., KEDDIE J.R., SINGH P., STOGGAL S.M., CAULKETT P.W.R., JONES G., COLLIS M.G. The in vitro pharmacology of ZM241385, a potent, non-xanthine, A2a selective adenosine receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:1096–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSIN D.L., ROBEVA A., WOODARD R.L., GUYENET P.G., LINDEN J. Immunohistochemical localization of adenosine A2A receptors in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;401:163–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUDOLPHI K.A., SCHUBERT P., PARKINSON F.E., FREDHOLM B.B. Neuroprotective role of adenosine in cerebral ischemia. TiPS. 1992;13:439–445. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90141-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFMANN S.N., LIBERT F., VASSART G., DUMONT J.E., VANDERHAEGHEN J.-J. A cloned G protein-coupled protein with a distribution restricted to striatal medium-sized neurons. Possible relationship with D1 dopamine receptor. Brain Res. 1990;519:333–337. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90097-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFMANN S.N., LIBERT F., VASSART G., VANDERHAEGHEN J.-J. Distribution of adenosine A2 receptor mRNA in the human brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1991;130:177–181. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEBASTIÃO A.M., RIBEIRO J.A. Evidence for the presence of excitatory A2 adenosine receptors in the rat hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;138:41–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90467-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEBASTIÃO A.M., RIBEIRO J.A. Adenosine A2 receptor-mediated excitatory actions on the nervous system. Progr. Neurobiol. 1996;48:167–189. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON LUBITZ D.K.E.J., LIN R.C.S., JACOBSON K.A. Cerebral ischemia in gerbils: effects of acute and chronic treatment with adenosine A2A receptor agonist and antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;287:295–302. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00498-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON LUBITZ D.K.E.J. Adenosine and cerebral ischemia: therapeutic future or death of a brave concept. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;365:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAN W., SUTHERLAND G.R., GEIGER J.D. Binding of the adenosine A2 receptor ligand [3H]CGS 21680 to human and rat brain: evidence for multiple affinity sites. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:1763–1771. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS M., SCHULZ R., HUTCHINSON A.J., DO H., SILLS M.A., JARVIS M.F. [3H]CGS 21680, an A2-selective adenosine receptor agonist directly labels A2 receptors in the rat brain. FASEB J. 1989;3:A1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU L.G., SAGGAU P. Adenosine inhibits evoked synaptic transmission primarily by reducing presynaptic calcium influx in area CA1 of hippocampus. Neuron. 1994;12:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOCCHI C., ONGINI E., CONTI A., MONOPOLI A., NEGRETTI A., BARALDI P.G., DIONISOTTI S. The non-xanthine heterocyclic compound SCH 58261 is a new potent and selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;276:398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]