Abstract

The cerebrovascular receptor(s) that mediates 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)-induced vasoconstriction in human cerebral arteries (HCA)has proven difficult to characterize, yet these are essential in migraine. We have examined 5-HT receptor subtype distribution in cerebral blood vessels by immunocytochemistry with antibodies selective for human 5-HT1B and human 5-HT1D receptors and also studied the contractile effects of a range of 5-HT receptor agonists and antagonists in HCA.

Immunocytochemistry of cerebral arteries showed dense 5-HT1B receptor immunoreactivity (but no 5-HT1D receptor immunoreactivity) within the smooth muscle wall of the HCA. The endothelial cell layer was well preserved and weak 5-HT1B receptor immunoreactivity was present.

Pharmacological experiments on HCA with intact endothelium showed that 5-carboxamidotryptamine was significantly more potent than α-methyl-5-HT, 2-methyl-5-HT and 5-HT in causing vasoconstriction. The 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists naratriptan, sumatriptan, zolmitriptan and 181C91 (N-desmethyl zolmitriptan), all induced equally strong contractions and with similar potency as 5-HT. The maximum contractile response was significantly less for avitriptan and dihydroergotamine. There was a significant correlation between vasoconstrictor potency and 5-HT1B- and 5-HT1D-receptor affinity, but not with 5-HT1A-, 5-ht1F or 5-HT2- receptor affinity.

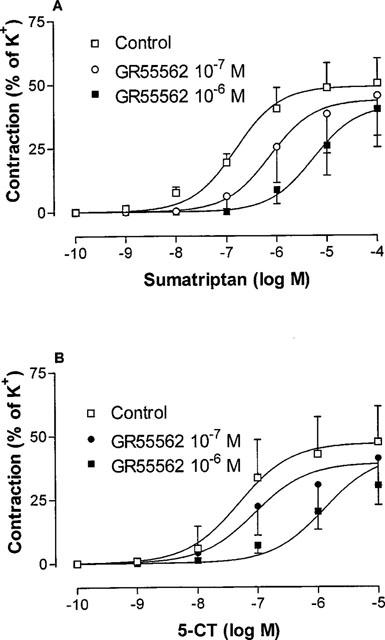

The 5-HT1B/1D-receptor antagonist GR 55562 (10−7–10−6 M) inhibited the contractile responses to sumatriptan and 5-CT in a competitive manner with a pKB value for GR 55562 of 7.4. Furthermore, ketanserin (10−7 M), prazosin (10−7 M), and sulpiride (10−7 M) were devoid of significant antagonistic activity of 5-HT-induced contraction in the HCA.

The results are compatible with the hypothesis that the 5-HT1B receptors play a major role in 5-HT-induced vasoconstriction in HCA.

Keywords: 5-HT receptors, immunocytochemistry, in vitro pharmacology, endothelium, smooth muscle

Introduction

Over several decades circumstantial evidence has been collected to implicate the involvement of serotonin in migraine headache. Serotonin is a powerful vasomotor agent of the intracranial vasculature (Humphrey & Feniuk, 1991; Friberg et al., 1991). The characterization of the 5-HT receptors involved in mediating the vasomotor effects of 5-HT in these vessels has proven difficult since up to 17 subtypes of 5-HT receptors exist at present, which can be divided into seven major classes, and selective agonists and antagonists are available for some, but not all, of these receptors (Hoyer et al., 1994).

The recently developed antimigraine drugs which act as acute abortive antimigraine therapies are agonists at 5-HT1B/1D-receptors (Weinshank et al., 1992; Ferrari & Saxena, 1995). These drugs cause vasoconstriction in human blood vessels both in vitro and in vivo (Hamel et al., 1993; Kaumann et al., 1994; van Es et al., 1995) and haemodynamic studies have shown a selective action in causing vasoconstriction in the cranial vascular bed compared to peripheral arteries (Perren et al., 1989). At the time of the discovery of sumatriptan, the prototypic drug in this class, only one subtype namely the 5-HT1B (or 5-HT1Dβ) was described in man and drug development was targeted against this receptor. Subsequently, molecular cloning revealed the existence of two subtypes, namely 5-HT1B- and 5-HT1D-receptors (Hamblin & Metcalf, 1991; Hartig et al., 1992; Jin et al., 1992; Peroutka & McCarthy, 1989), and since in man these receptors are closely related, sumatriptan-like drugs have similar affinity at both subtypes (Weinshank et al., 1992). Thus, in human blood vessels vasoconstrictor potency can correlate with affinity at both 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors (Hamel & Bouchard, 1991; Hamel et al., 1993; Jansen et al., 1992; 1993; Kaumann et al., 1994). Interestingly, studies with RT–PCR or Northern blot hybridization delineating the distribution of mRNA coding for 5-HT receptors in human cerebral vasculature, have shown expression of 5-HT1B receptor mRNA but not 5-HT1D receptor mRNA (Hamel et al., 1993). More recently immunocytochemical studies using selective antibodies have shown expression of 5-HT1B and not 5-HT1D receptor protein in human middle meningeal (dural) artery (Longmore et al., 1997). This contrasts with human trigeminal ganglia containing the cell bodies of sensory neurones innervating cranial vessels which express mRNA or receptor protein coding for both receptor subtypes, indicative of a prejunctional localization (Bouchelet et al., 1996; Hamel et al., 1993; Rebeck et al., 1994; Longmore et al., 1997). However, the expression of 5-HT1B receptor protein or its mRNA in blood vessels does not allow the extrapolation that this receptor mediates the vasoconstrictor action of 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists. For example, mRNA coding for 5-ht1F receptors is also present in blood vessels yet selective 5-ht1F receptor agonists are devoid of vasoconstrictor properties (Johnson et al., 1997).

The aim of the present studies was to further characterize the contractile 5-HT receptors in human cerebral arteries since previous studies only have examined the dura mater middle meningeal artery (Longmore et al., 1998; Razzaque et al., 1999) or the extracranial temporal artery (Verheggen et al., 1996; 1998) which according to recent positron emission tomography studies may have a less likely role in the primary part of migraine (Weiller et al., 1995) or cluster headache attacks (May et al., 1998). We have used two strategies; (i) receptor mapping studies using immunocytochemistry with selective antibodies towards 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors; (ii) a pharmacological approach to correlate the vasoconstrictor potency of a series of 5-HT receptor agonists with their affinity at 5-HT receptors determined in previously reported binding studies and also to examine the effects of selective antagonists on vasoconstrictor responses in human cerebral arteries (HCA).

Methods

Immunocytochemistry

Human tissue samples

Cerebral arteries from the base of the brain and on the cortical surface were obtained post mortem as routine histopathological samples from the University Hospital, Lund, Sweden. Specimens were collected in accordance with Swedish legislation (Transplantation act, β1).

Preparations of sections for immunohistochemistry

Segments of middle cerebral arteries (2–3 mm in length) and cortical surface arteries were fixed (7 days) by immersion in a solution of 4% formaldehyde in physiological saline (Sigma). The tissues were processed for immunohistochemical studies as previously described (Longmore et al., 1997). Briefly, after fixation the tissue blocks were processed to paraffin wax, sectioned (7 μm) and collected on to Fischer Superfrost/plus slides. The sections were air dried, de-waxed using xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohols. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked by immersion in 0.3% H2O2 in methanol (1 h, room temperature) and washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma). The sections were then exposed to the primary antibodies (i.e. 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors, α-actin and Ulex europaeus smooth muscle and endothelial cell markers respectively). Note for the 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptor antibodies, the sections were subjected to antigen retrieval techniques prior to exposure to the primary antibody. Following overnight incubation with the primary antibodies (4°C, saturated humidity) the sections were exposed to the secondary antibody (biotinylated goat anti rabbit IgG, Vectastain Elite Kit, 1 h at room temperature), washed in PBS and immersed in Avidin-Biotin Complex (Vectastain Elite Kit, 1 h, room temperature). Following further washing the immunoreactivity was visualized using di-amino benzidine (0.0025% DAB in PBS with 0.03% H2O2) as the chromagen which gives an orange/brown staining. All sections were counterstained with haematoxyllin (blue/purple stain) to visualize cell nuclei. Light microscopy was performed on a Leica (DMRB) microscope using normal Kohler illumination.

In vitro tissue bath experiments

Tissue samples

Cerebral (cortex) arteries were obtained from patients undergoing surgery for intracranial tumours or removed at autopsy within 12 h after death. All vessels were placed in buffer solution aerated with 5% CO2 in oxygen and immediately transported to the laboratory for investigation. The study was approved by the Human Ethic Committee of the University of Lund.

Vasomotor responses

The vessels were dissected free under a microscope and cut into cylindrical segments (1–2 mm long 300–600 μm in diameter with intact endothelium). The segments were mounted on two metal prongs, one of which was connected to a force displacement-transducer (FT03C, Grass Inc, U.S.A.), and the other to a displacement device. The position of the holder could be changed by means of a movable unit allowing fine adjustments of vascular tension by varying the distance between the metal prongs. The experiments were continuously recorded by the software program Chart® (AD Instruments, U.K). The mounted specimens were immersed in temperature-controlled (37°C) tissue baths containing a buffer solution of the following composition (mM): NaCl 119, NaHCO2 15, KCl 4.6, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 1.5, glucose 5.5. The buffer solution was continuously gassed with 5% CO2 in O2 giving a pH of 7.4. The segments were loaded under an initial resting tension of 3 mN and they were allowed to stabilize at this tone for 1 h. The resting tone for small cerebral arteries of the present size was determined in previous experiment on length-tension relationships in Ca+2 free conditions and vessels contracted by potassium depolarization (Högestätt et al., 1983; and data not shown).

The contractile capacity of each vessel segment was examined by exposure to a potassium-rich (60 mM) buffer solution which had the same composition as the standard solution except that some of the NaCl was exchanged for an equimolar concentration of KCl. These contractions served as internal standards and were set as 100%. When two reproducible contractions had been achieved (variation less than 10%) the vessels were used for further studies (for further details see Jansen et al., 1992; 1993).

Vasoconstrictor effects of the agonists were examined by obtaining cumulative concentration effect curves to each of the drugs. One or two concentration response curves per artery segment for each patient only in the results. The mean of these was used as one value for this patient. There was no desensitization when repeating agonist doses. For the experiments with antagonists matched pairs were always studied in parallel; i.e. one segment received agonist only and the another segments from the same vessel agonist plus antagonist in the selected concentration.

Analysis of data

The contractile response to each agonist was expressed as a percentage of the potassium-evoked contraction. The program GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, U.S.A.) was used to obtain a fitted curve to calculate Emax (maximum contraction) and pEC50 values. Maximum effect of contraction=Emax. The potency of the agonists is expressed as pEC50 values (negative logarithm of the molar concentration of agonist inducing half of the maximum response). The data are expressed as mean values±95% confidence limits, N refers to the number of patients from whom the vessels were collected. Statistically significant differences were determined with Wilcoxon signed rank test. P<0.05 was considered significant. For experiments with antagonists, agonist concentration-effect curves agonist were performed in the absence (control) and presence of each antagonist. The dissociation constant for the agonist, pKB, was calculated as previously described (see Tallarida et al., 1979).

Correlations between agonist vasoconstrictor potency and receptor affinity were made using linear regression analysis (expressed as pEC50 values taken from Table 1) of the agonists in the HCA and the IC50 values obtained at 5-HT receptor subtypes taken from binding sites in mammalian tissue previously reported (for references see Hoyer et al., 1994 and Razzaque et al., 1999).

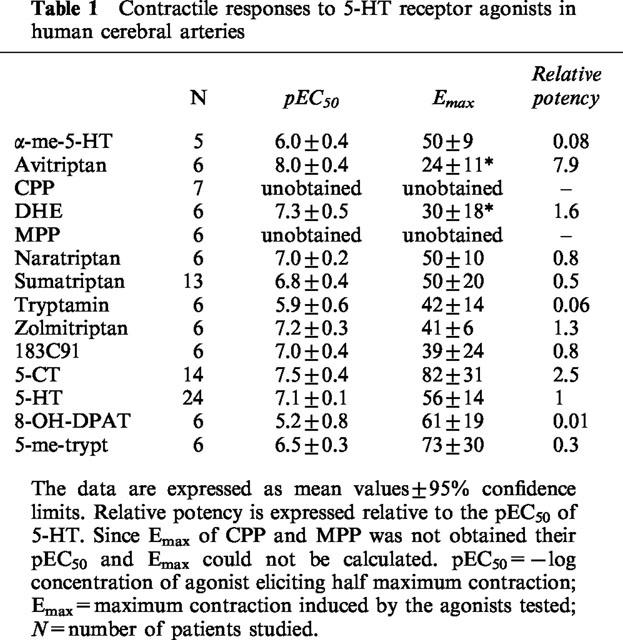

Table 1.

Contractile responses to 5-HT receptor agonists in human cerebral arteries

Drugs

The following agents were used in the experiments: 1-(3-Chlorophenyl) piperazine hydrochloride (CPP) and 1-(2-methoxyphenyl) piperazine hydrochloride (MPP) from RBI, U.S.A.; 5-hydroxytryptamine hydrochloride (5-HT) from Sigma, U.S.A.; tryptamine from Sigma, U.S.A. 5-carboxamidotryptamine hydrochloride (5-CT), 8-hydroxy-DPAT hydrobromide (8-OH-DPAT), 5-methoxytryptamine (5-me-trypt), α-methyl-5-hydroxytryptamine hydrochloride (α-me-5-HT), dihydroergotamine, GR55562, ketanserin, methiothepine, methysergide, naratriptan, sumatriptan, sulpiride, zolmitriptan and 183C91 (N-desmethyl zolmitriptan) (were all gifts from Glaxo Wellcome, U.K.) and avitriptan (a gift from Bristol-Meyers Squibb, U.S.A.). All the drugs were dissolved in 0.9% saline. The concentrations are expressed as the final molar concentration in the tissue bath.

Results

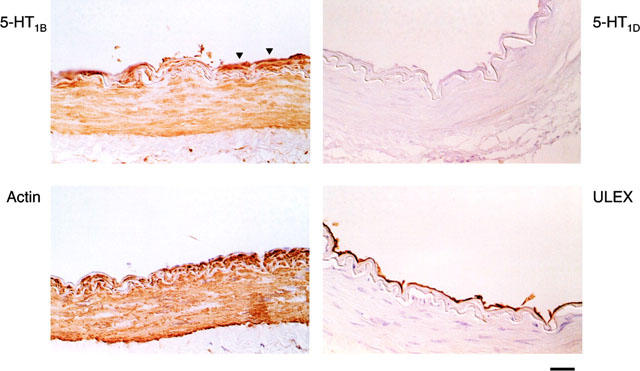

Immunohistochemical studies

Cortical cerebral arteries were obtained from three donors and representative immunocytochemical findings are shown in Figure 1. All of the arteries had a well developed smooth muscle layer (defined by anti-α-actin immunostaining) and a well preserved endothelial layer (defined by immunostaining to Ulex europaeus). Specific and dense 5-HT1B-receptor like immunostaining was seen on the smooth muscle cell layer of the small cerebral artery on the cortical surface (approximate diameters 50–500 μm) (Figure 1) and on the middle cerebral artery (data not shown). 5-HT1D- receptor immunostaining was not detected within the vessel wall. In cerebral arteries 5-HT1B-immunoreactivity was also detected in the endothelial cell layer, albeit slightly weaker (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative immunohistochemical findings in small arteries on the human cerebral cortex. Immunoreactivity (ir) was detected using di-amine benzidine as the chromagen which gives orange/brown staining and haematoxylin was used as a counterstain to detect cell nuclei (blue/purple stain). Thin (7 μm) sections of the artery were obtained and high power micrographs of parts of these sections are shown. Panel upper right shows that 5-HT1D ir was not detected; Panel upper left shows that 5-HT1B ir was detected on the endothelial layer (arrows) and that dense 5-HT1B ir was detected on the smooth muscle wall of arteries and arterioles. The endothelial layer was defined using Ulex europeas (lower right) and the smooth muscle layer was defined using anti α-actin (lower left).

In vitro pharmacology: vasoconstrictor effects of agonists

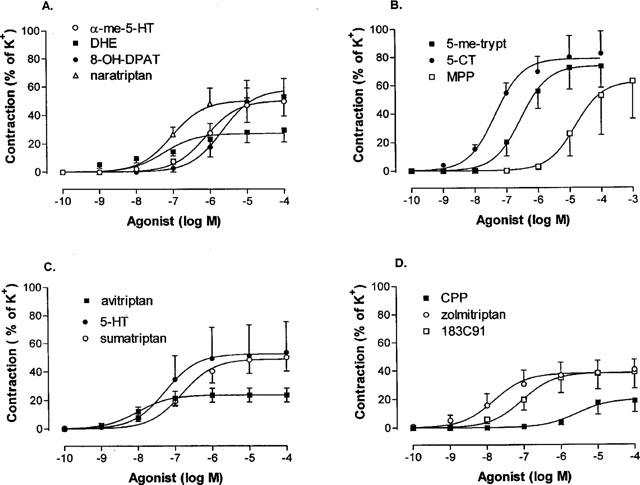

The agonists produced vasoconstrictor effects in human isolated cerebral arteries and the concentration-effect curves are shown in Figure 2 and the Emax and EC50 values are summarized in Table 1. The agonists produced contractions that varied between approximately 20–80% of the contraction elicited by 60 mM K+. There was considerable variation across individual segments in the size of the maximum contraction to each of the agonists and this is also consistent with the considerable inter-individual variations. Avitriptan and dihydroergotamine had significantly lower Emax compared to the others, which did not differ significantly from that of 5-HT. Agonist potency order was avitriptan >5-CT=DHE=zolmitriptan =183C91=5-HT = sumatriptan = 5-me-trypt>α-me-5 HT=8-OH-DPAT. This order compares favourably with published studies (Hamel & Bouchard, 1991; Hamel et al., 1993; Jansen et al., 1992; 1993).

Figure 2.

Concentration-effect curves to 5-HT receptor agonists in human isolated cerebral arteries. Contractile responses were expressed as a percentage of the contraction evoked by 60 mM KC1 (=100%). (A) Effect of α-methyl 5-HT, dihydroergotamine (DHE), 8-OH-DPAT and naratriptan; (B) 5-methoxytryptamine, 5-CT and MPP; (C) avitriptan, 5-HT and sumatriptan; (D) CPP, zolmitriptan and 183 C91. Points represent means±s.e.mean. Curves were fitted to the mean data points using non-linear regression analysis (Graph Pad Prism).

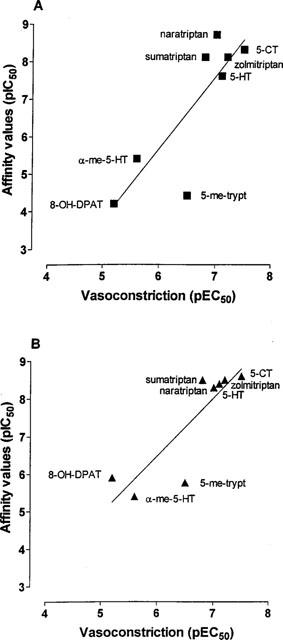

Correlation between vasoconstrictor potency and binding affinities at 5-HT receptors

For the series of agonists used, there was a significant correlation between vasoconstrictor potency in HCA and IC50 values obtained from human cloned 5-HT1B (r2=0.70; P<0.05) and 5-HT1D receptors (r2=0.75; P<0.05) (see Figure 3). The regression lines did not significantly differ from unity. The relationship between 5-HT1A, 5-ht1F and 5-HT2A binding sites and vasoconstrictor potency did not achieve statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Correlations between vascocontrictor potency in human isolated cerebral artery (pEC50) with measurements of affinity (IC50) at 5-HT1B (A) and 5-HT1D-receptors (B) obtained in binding experiments (see Hoyer et al., 1994; Razzaque et al., 1999). Linear regression analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism. Significant correlations (P<0.05) were found between vasoconstrictor potency and 5-HT1B-receptor affinity (r2=0.70) and 5-HT1D-receptor affinity (r2=0.75) but not with 5-HT1A, 5-ht1F or 5-HT2 receptor affinity (data not shown).

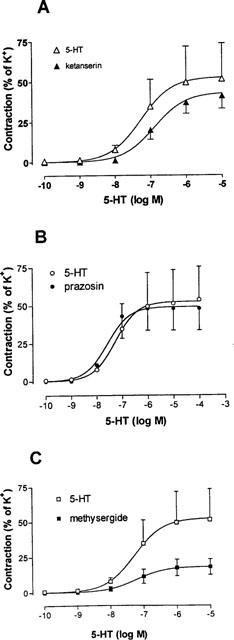

Antagonism

Ketanserin (10−9–10−6 M), 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, and prazosin (10−7 M), α1-adrenoceptor antagonist, had no effect on 5-HT (Figure 4) or 5-CT (data not shown) evoked contractions in HCA. Methysergide (10−7 M) caused a significant (P<0.05) reduction in the maximum contractile response evoked by 5-HT but with no change in the pEC50 value (Figure 4). Sulpiride (dopamine-receptor blocker) (10−6 M) was without effect on 5-HT induced contractions (data not shown). The recently available 5-HT1B/1D antagonist GR 55562 (10−7–10−6 M) resulted in a parallel shift to the right of both sumatriptan and 5-CT concentration-effect curves without any significant reduction in Emax (Figure 5). The mean pKB value for GR 55562 was 7.4 (range 7.3–7.5).

Figure 4.

Vasoconstrictor effects of 5-HT in human isolated cerebral arteries in the absence and presence of the antagonists: (A) ketanserin (10−7 M), (B) prazosin (10−7 M) and (C) methysergide (10−7 M). Contractile responses were expressed relative to the size of the contraction evoked by 60 mM KCl (=100%). Points represent means±s.e.mean. Curves were fitted to the mean data points using non-linear regression analysis (Graph Pad Prism).

Figure 5.

Vasoconstrictor effects of (A) sumatriptan and (B) 5-CT in human isolated cerebral arteries in the absence and presence of GR 55562 (10−7 or 10−6 M). Contractile responses were expressed relative to size of contraction evoked by 60 mM KCl (=100%). Points represent means±s.e.mean. Curves were fitted to the mean data points using non-linear regression analysis (Graph Pad Prism).

Discussion

The 5-HT1B and/or 5-HT1D-receptors are recognized as key-target for drugs effective in the acute treatment of migraine (Humphrey & Feniuk, 1991; Humphrey et al., 1988). Within the intracranial circulation, the key area for the treatment of migraine, 5-HT1-receptors are present in the smooth muscle cells of the middle meningeal (dura mater) arteries and on cerebral arteries (Jansen et al., 1992; 1993, Parsons et al., 1989; Hamel et al., 1993). 5-HT1-receptors have been claimed to act presynaptically to inhibit neurogenic plasma-protein extravasation in the dura mater of rodents (Buzzi & Moskowitz, 1991). These responses are thought to be the most pertinent locations for the therapeutic actions of 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists in the acute treatment of migraine attacks.

Previously, studies have demonstrated that in human middle meningeal arteries (a dural artery), vasoconstrictor effects to 5-HT1B/1D-receptor agonists are mediated via activation of 5-HT1B-receptors (Longmore et al., 1997; Razzaque et al., 1999). The present study shows for the first time that the new antimigraine 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists zolmitriptan (and its des-methyl metabolite BW183C91), naratriptan and avitriptan cause contraction of human cerebral arteries removed intra-operatively and thus devoid of any post mortem changes. Naratriptan, zolmitriptan and 183C91 were only slightly more potent than sumatriptan (the prototypic 5-HT1B/1D-receptor agonist) which is in line with differences in the affinities of these drugs at human cloned 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors (Martin et al., 1997). Their Emax values were not different compared to the Emax value of sumatriptan.

The data are consistent with those reported by Martin et al. (1997) where zolmitriptan was noted to be 3 fold more potent then sumatriptan and produced a similar maximum contractile response in primate basilar artery. Avitriptan was the most potent agonist tested in HCA, however, the maximum contractile response was significantly lower than that of sumatriptan. Interestingly, avitriptan and BMS-181885 (an avitriptan analogue) have also been shown to produce smaller contractions than sumatriptan in human coronary artery (De Vries et al., 1999). The results for sumatriptan correlate well with its previously reported effects in human cranial arteries (Parsons et al., 1989; Jansen et al., 1992; 1993; Hamel et al., 1993). Naratriptan was also a full agonist with a maximum equal to that of 5-HT and a potency not significantly different from that of sumatriptan which agrees well with a previous report (Connor et al., 1997).

GR 55562 is a recently developed selective 5-HT1B/1D-receptor antagonist which has been found to cause a parallel shift of sumatriptan induced concentration-effect curves of dog and monkey basilar arteries (Connor & Beattie, 1996). GR 55562 was found to antagonise contractions evoked by both sumatriptan and 5-CT in similar concentrations as studied before (Connor & Beattie, 1996), which is consistent with activity of both of these agonists and the antagonist at 5-HT1B/1D-receptors. Connor & Beattie (1996) also revealed the binding characteristics of GR55562 at various 5-HT receptors. The reported pKi/pKB values were for 5-HT1B 7.4, for 5-HT1D 6.2, for 5-ht1F 5.6, for 5-HT2A 5.6, and considerably less for all other receptor sites studied. This antagonist thus appears to show some selectivity for the 5-HT1B receptor. Thus, our calculated pKB of 7.4, using sumatriptan and 5-CT as agonists, correlates best with the binding data for the 5-HT1B receptor site.

In human isolated temporal arteries, contractile responses to 5-HT are sensitive to antagonism by ketanserin and to a lesser extent to methiothepin (5-HT2- and 5-HT1-receptor antagonists, respectively) and it has been estimated that activation of the 5-HT2 receptor contributes to at least 80% of the response to 5-HT in this blood vessel (Verheggen et al., 1996; Jansen et al., 1993). In the present study of HCA the contractile responses to 5-HT were insensitive to ketanserin but were depressed by methysergide (without any change in pEC50 values). This is consistent with the partial agonistic effects of methysergide at 5-HT1B/1D-receptors which would be expected to reduce the response to 5-HT, a full agonist. These data suggest that in HCA (in contrast to temporal arteries) the response to 5-HT is mediated almost exclusively via activation of 5-HT1B/1D receptors with little or no involvement of 5-HT2 receptors. Similar findings have been reported for human cerebral arteries where the maximal contraction to sumatriptan (a drug devoid of effects of 5-HT2 receptors) was identical to that of 5-HT (Hamel et al., 1993; Jansen et al., 1992;1993). In HCA 5-HT-induced contractions were not blocked by prazosin (an α1-adrenoceptor antagonist) or by sulpiride (a dopamine receptor antagonist) confirming the lack of involvement of other vascular monoamine receptors.

The rank order of potency of the different 5-HT receptor agonists in HCA compares well with the agonist potency order obtained in previous studies. This pharmacological profile is also in agreement with that observed for human cloned 5-HT receptor subtypes expressed in cell lines (Levi et al., 1992; Weinshank et al., 1992; Oksenberg et al., 1992; Demchyshyn et al., 1992). Correlation analysis of cerebral vascular agonist potencies and measurements of affinity for cloned 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-ht1F and 5-HT2A receptors obtained in binding studies showed significant correlations only for the human 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D-receptors. This agrees well with the results of others for cerebral (Hamel et al., 1993) and middle meningeal arteries (Razzaque et al., 1999). However, the correlation was slightly better for the 5-HT1B- subtype than for the 5-HT1D -subtype of receptors but the criteria was not sufficient to discriminate between them. This is slightly different compared to the observations for bovine vasculature where significant correlation could be obtained for the 5-HT1B-subtype but not for the 5-HT1D-subtype (Hamel et al., 1993). The correlation analysis performed by Razzaque et al. (1999) also examined 5-HT1F receptors, however, there was no correlation between the binding and the vasomotor responses which agrees well with our data on the HCA. It should however, be recognized that correlations employed between agonist binding affinity at 5-HT receptor sites and vasoconstrictor potency are limited by differences in agonist intrinsic activity (as evidenced in Table 1), which are not accounted for by the correlations.These correlations may therefore only provide supportive evidence.

The pharmacological approach showed that the vasoconstrictor effects of 5-HT in human cerebral arteries could be mediated by either 5-HT1B or 5-HT1D receptors. Due to the lack of adequately selective ligands it was not possible to discriminate fully between these two 5-HT receptor subtypes although the data are most in support of the 5-HT1B -subtype. Therefore, as an alternative, we used an immunohistochemical approach with selective antibodies and showed the presence of the 5-HT1B-receptor protein but not 5-HT1D- receptor protein within the smooth muscle wall of small cerebral arteries from both the cortical surface of the brain (Figure 1) and the middle cerebral artery (data not shown). This suggests that the vasoconstrictor effect to 5-HT receptor active agonists are mediated via the 5-HT1B-receptor subtype in the HCA. It is worth noticing that we observed also 5-HT1B immunostaining in the endothelial cells. This could represent a dilatory capability of 5-HT via this receptor site. In fact, a previous study on cat and human cerebral arteries has revealed a relaxant response to 5-HT in arteries where the contractile effect of 5-HT first had been antagonized with irreversible blockade by phenoxybenzamine (Edvinsson et al., 1978). Further support for this possibility was recently given by Riad et al. (1998) who observed with an immunogold technique 5-HT1B-receptors in intracerebral microvascular endothelium and smooth muscle cells. Previously, it has been reported that there is a differential distribution of 5-HT1B/1D -receptors within the human trigeminovascular system with 5-HT1B receptors being located in middle meningeal (dural) arteries and 5-HT1D -receptors on trigeminal sensory neurones (Longmore et al., 1997). The present study has for the first time demonstrated the selective expression of the 5-HT1B -receptor protein in HCA. These cerebral arteries are considered involved in the pathophysiology of migraine headache attacks and are potential site of action of the triptans.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the Swedish Medical Research Council (Grant Nos 5958 and 11238).

Abbreviations

- 5-CT

5-carboxamidotryptamine

- CPP

1-(3-chlorophenyl piperazine

- 183 C91

N-desmethyl zolmitriptan

- DHE

dihydroergotamine

- 8-OH-DPAT

8-hydroxy-DPAT

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- HCA

human cerebral artery

- MPP

1-(2-methoxyphenyl) piperazine

- 5-me-tryp

5-methoxytryptamine

- α-me-5-HT

α-methyl-5-hydroxytryptamine

References

- BOUCHELET I., COHEN Z., BRUCE C., SEGUELA P., HAMEL E. Differential expression of sumatriptan-sensitive 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in human trigeminal ganglia and cerebral blood vessels. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;60:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUZZI M.G., MOSKOWITZ M.A. Evidence for 5-HT1B/1D receptors mediating the anti-migraine effect of Sumatriptan and dihydroergotamine. Cephalalgia. 1991;11:165–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1991.1104165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNOR H.E., BEATTIE D.T.5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor subtypes and migraine Migraine: Pharmacology and Genetics 1996London, Chapman and Hall; 18–27.Sandler M, Ferrari M & Harnett S, eds pp [Google Scholar]

- CONNOR H.E., FENIUK W., BEATTIE D.T., NORTH P.C., OXFORD A.W., SAYNOR D.A., HUMPHFREY P.P.A. Naratriptan: biological profile in animal models relevant to migraine. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:145–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1703145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMCHYSHYN L., SUNAHARA R.K., MILLER K., TEITLER M., HOFFMAN B.J., KENNEDY J.L., SEEMAN P., VAN TOL H.H.M., NIZNIK H.B. A human serotonin 1D receptor variant (5-HT1Dα) encoded by an intronless gene on chromosome 6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:5522–5526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VRIES P., VILLALON C.M., HEILIGERS J.P.C., SAXENA P.R.Porcine carotid haemodynamic effects of alniditan, a selective 5-HT1B/1D-receptor ligand Br. J. Pharmacol. Proc. 1999Suppl.(in press)

- EDVINSSON L., HARDEBO J.E., OWMAN C. Pharmacological analysis of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in isolated intracranial and extracranial vessels of cat and man. Circ. Res. 1978;42:143–151. doi: 10.1161/01.res.42.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRARI M.D., SAXENA P.R. 5-HT1 receptors in migraine pathophysiology and treatment. Eur. J. Neurol. 1995;2:5–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.1995.tb00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIBERG L., OLESEN J., IVERSEN H.K., SPERLING B. Migraine pain associated with middle cerebral artery dilation: reversal by sumatriptan. Lancet. 1991;338:13–17. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90005-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMBLIN M.W., METCALF M.A. Primary structure and functional characterisation of a human 5-HT1D -type serotonin receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMEL E., BOUCHARD D. Contractile 5-HT1 receptors in human isolated pial arterioles: correlation with 5-HT1D binding sites. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMEL E., FAN E., LINVILLE D., TING V., VILLEMURE J.G., CHIA L.S. Expression of mRNA for the serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine1D receptor subtype in human and bovine cerebral arteries. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARTIG P.R., BRANCHEK T.A., WEINSHANK R.L. A subfamily of 5-HT1D receptor genes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13:152–159. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HÖGESTÄTT E.D., ANDERSSON K-E., EDVINSSON L. Mechanical properties of rat cerebral arteries as studied by a sensitive device for recording of mechanical activity in isolated small blood vessels. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1983;1771:49–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1983.tb07178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOYER D., CLARKE D.E., FOZARD J.R., HARTIG P.R., MARTIN G.R., MYLECHARANE E.J., SAXENA P.R., HUMPHREY P.P.A. VII International Union of Pharmacology Classification of Receptors for 5-Hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin) Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:157–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUMPHREY P.P.A., FENIUK W. Mode of action of the anti-migraine drug sumatriptan. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991;12:444–446. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90630-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUMPHREY P.P.A., FENIUK W., PERREN M.J., CONNOR H.E., OXFORD A.W., COATIS I.H., BUTINA D. GR 43175, a selective agonist for the 5-HT1-like receptor in dog isolated saphenous vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;94:1123–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSEN I., EDVINSSON L., MORTENSEN A., OLESEN J. Sumatriptan is a potent vasoconstrictor of human dural arteries via a 5-HT1-like receptor. Cephalalgia. 1992;12:202–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1992.1204202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSEN I., OLESEN J., EDVINSSON L. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor characterisation of human cerebral, middle meningeal and temporal arteries: regional differences. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1993;147:141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN H., OKSENBERG H., ASHKENZAI A., PEROUTKA S.J., DUNCAN A.M.V., ROZMAHEL R., YANK Y., MENGOD G., PALACIOS J.M., O' DOWD B.F. Characterisation of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine1B receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:5735–5738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON K.W., SCHAUS J.M., DURKIN M.M., AUDIA J.E., KALDOR S.W., FLAUGH M.E., ADHAM N., ZGOMBICK J.M., COHEN M.L., BRANCHEK T.A., PHEBUS L.A. 5-HT1F receptor agonists inhibit neurogenic dural inflammation in guinea pigs. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2237–2240. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199707070-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUMANN A.J., FRENKEN M., POSIVAL H., BROWN A.M. Variable participation of 5-HT1-like receptors and 5-HT2 receptors in serotonin-induced contraction of human isolated coronary arteries. 5-HT1-like receptors resemble cloned 5-HT1Dβ receptor. Circulation. 1994;90:1141–1153. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVY F.O., GUDERMANN T., PEREZ-REYES E., BIRNBAUMER M., KAUMANN A.J., BIRNBAUMER L. Molecular cloning of a human serotonin receptor (S12) with a pharmacological profile resembling that of the 5-HT1D subtype. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:7553–7562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LONGMORE J., RAZZAQUE Z., SHAW D., DAVENPORT A.P., MAGUIRE J., PICKARD J.D., SCHOFIELD W.N. &, HILL R.G. Comparison of the vasoconstrictor effects of rizatriptan and sumatriptan in human isolated cranial arteries: immunohistological demonstration of the involvement of 5-HT1B-receptors. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998;46:577–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00821.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LONGMORE J., SHAW D., SMITH D., HOPKINS R., MCALLISTER G., PICKARD J.D., SIRINATHSINGHJI D.J.S., BUTLER A.J., HILL R.G. Differental distribution of 5-HT1B- and 5-HT1D immunoreactivity within the human trigemino-cerebrovascular system: implications for the discovery of new antimigraine drugs. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:833–842. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1708833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN G.R., ROBERTSON A.D., MACLENNAN S.J., PRENTICE D.J., BARRETT V.J., BUCKINGHAM J., HONEY A.C., GILES H., MONCADA S. Receptor specificy and trigemino-vascular inhibitory actions of a novel 5-HT1B/1D receptor partial agonist, 311C90 (zolmitriptan) Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:157–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAY A., BAHRA A., BÜCHEL C., FRACKOWIAK R.S.J., GOADSBY P.J. Hypothalamic activation in cluster headache attacks. Lancet. 1998;352:275–278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKSENBERG D., MARSTERA S.A., O'DOWD B.F., JIN H., HAVLIK S., PEROUTKA S.J., ASHKENAZI A. A single amino-acid difference confers major pharmacological variation between human and rodent 5-HT1D- receptors. Nature (Lond.) 1992;360:161–163. doi: 10.1038/360161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARSONS A.A., WHALLEY E.T., FENIUK W., CONNOR H.E., HUMPHREY P.P.A. 5-HT1-like receptors mediate 5-hydroxytryptamine-induced contraction of human isolated basilar artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;96:434–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEROUTKA S.J., MCCARTHY B.G. Sumatriptan (GR 43175) interacts selectively with 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D binding sites. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;163:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERREN M.J., FENIUK W., HUMPHREY P.P.A. The selective closure of feline carotid arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) by GR43175. Cephalalgia. 1989;9 Suppl 9:41–46. doi: 10.1111/J.1468-2982.1989.TB00071.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAZZAQUE M.A., HEALD J., PICKARD J.D., MASKELL L., BEER M.S., HILL R.G., LONGMORE J. Vasoconstriction in human isolated middle meningeal arteries: determining the contribution of 5-HT1B and 5-HT1F –receptor activation. Br. J. Clin. Phamacol. 1999;47:75–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REBECK G.W., MAYNARD K.I., HYMAN B.T., MOSKOWITZ M.A. Selective 5-HT1Dα serotonin receptor gene expression in trigeminal ganglia: Implications for antimigraine drug development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U.S.A. 1994;91:3666–3669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIAD M., TONG X.-K., EL MESTIKAWY S., HAMON M., HAMEL E., DESCARRIES L. Endothelial expression of the 5-hydroxytryptamine1B antimigraine drug receptor in rat and human brain microvessels. Neuroscience. 1998;86:1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALLARIDA R.J., COWN A., ADLER M.W. pA2 and receptor differentiation: a statistical analysis of competitive antagonism. Life Sci. 1979;25:637–654. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN ES N.M., BRUNING T.A., CAMPS J., CHANG P.C., BLAUW G.J., FERRARI M.D., SAXENA P.R., VAN ZWIETEN P.A. Assessment of peripheral vascular effects of antimigraine drugs in humans. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:288–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.1504288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERHEGGEN R., FREUDENTHALER S., MEYER-DULHEUER F., KAUMANN A.J. Participation of 5-HT1-like and 5-HT2A receptors in the contraction of human temporal artery by 5-hydroxytryptamine and related drugs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:283–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERHEGGEN R., HUNDESHAGEN A.G., BROWN A.M., SCHINDLER M., KAUMANN A.J. 5-HT1B receptor-mediated contractions in human temporal artery: evidence from selective antagonists and 5-HT receptor mRNA expression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:1345–1354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEILLER C., MAY A., LIMMROTH V., JÜPTNER M., KAUBE H., SCHAYCK R.V., COENEN H.H., DIENER H.C. Brain stem activation in spontaneous human migraine attacks. Nat. Med. 1995;1:658–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEINSHANK R.L., ZGOMBICK J.M., MACCHI M., BRANCHEK T.A., HARTIG P.R. The human serotonin 1D receptor is encoded by a subfamily of two distinct genes: 5-HT1Dα and 5-HT1Dβ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:3630–3634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]