Abstract

Whole cell patch clamp techniques were used on thin brainstem slices to investigate the effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) on gastrointestinal-projecting dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) neurones. Neurones were identified as projecting to the stomach (n=122) or intestine (n=84) if they contained the fluorescent tracer Dil after it had been applied to the gastric fundus, corpus or antrum/pylorus or to the duodenum or caecum.

A higher proportion of intestinal neurones (69%) than gastric neurones (47%) responded to 5-HT with a concentration-dependent inward current which was antagonized fully by the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin (1 μM).

Stimulation of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) induced inhibitory synaptic currents that were reduced in amplitude by application of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OHDPAT (1 μM) or the 5-HT1A/1B receptor agonist TFMPP (1 μM) in 61% and 52% of gastric- and intestinal-projecting neurones, respectively. 5-HT also significantly reduced the frequency but not the amplitude of spontaneous inhibitory currents.

These data show that 5-HT excites directly a larger proportion of intestinal projecting neurones than gastric-projecting neurones, as well as inhibiting synaptic transmission from the NTS to the DMV. These data imply that the response to DMV neurones to 5-HT may be determined and classified by their specific projections.

Keywords: DMV, brainstem, 5-HT, parasympathetic, preganglionic, gastrointestinal, electrophysiology

Introduction

The dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) contains the cell bodies of preganglionic parasympathetic neurones that supply the motor innervation to subdiaphragmatic viscera (see Gillis et al., 1989). Sensory information (mechanical, osmotic, chemical and caloric) perceived by discrete areas of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the oesophagus to the colon are transmitted via vagal afferent fibres and are received by cells within different subnuclei of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS). For example, gastric sensory projections are received principally in the gelatinosus and medialis subnuclei of the NTS, while intestinal sensory projections are received mainly in the commissuralis (comNTS) and medialis subnuclei; oesophageal sensory projections are received in the NTS subnucleus centralis (cenNTS), (Altschuler et al., 1989; 1991; Zhang et al., 1995; Rogers et al., 1999). These distinct subnuclei of the NTS then integrate this information and provide both excitatory and inhibitory inputs to the DMV via a monosynaptic pathway (Bertolino et al., 1997; Travagli et al., 1991; Rogers et al., 1999; Fukuda et al., 1987; Champagnat et al., 1986; Willis et al., 1996). Higher CNS centres such as the raphe nuclei and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus exert modulation at the level of these synaptic connections.

Within the caudal brainstem, a serotonergic input to the dorsal vagal complex (DVC, i.e., DMV and NTS) is provided by both medullary raphe neurones (McCann et al., 1989; Hornby et al., 1990; Palkovits et al., 1986) and vagal afferent neurones (Nosjean et al., 1990; Izzo et al., 1993; Sykes et al., 1994). In addition, autoradiographic studies of the DVC have revealed discrete distributions of 5-HT receptors. In detail, 5-HT1A receptors are localized throughout the NTS, predominantly in the cenNTS, although low quantities are also found in the DMV (Manaker & Verderame, 1990; Thor et al., 1992a, 1992b). 5-HT1B receptors are distributed mainly in NTS sunucleus gelatinosus and the DMV (Manaker & Verderame, 1990; Thor et al., 1992a, 1992b), while 5-HT2 receptors are scattered on DMV somata (Wright et al., 1995). 5-HT3 receptors are present throughout the DVC (Steward et al., 1993). These studies indicate that a multitude of 5-HT receptor subtypes may be present within the DVC, providing means by which 5-HT may exert a fine modulation of vagal activity.

Vagal preganglionic motoneurones exhibit diverse responses to exogenous application of 5-HT. For example, 5-HT acts on gastrointestinal preganglionic neurones to increase gastric acid secretion (McTigue et al., 1992; Krowicki & Hornby, 1995; Yoneda & Tache, 1995; Chi et al., 1996; Varanasi et al., 1997), while 5-HT, acting through 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B/1D receptors, exerts opposing effects on bronchoconstrictor preganglionic neurones (Bootle et al., 1998) whereas cardiac vagal motorneurones are excited by activation of 5-HT1A receptors (Sporton et al., 1991).

Using in vivo extracellular recording techniques, approximately 40% of NTS neurones were excited by 5-HT, 30% were inhibited and the remaining 20% of neurones were unaffected (Wang et al., 1997). The excitatory effects of 5-HT were mimicked by both 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptor agonists, and, since 5-HT1A receptors are known to be inhibitory (see Bobker & Williams, 1993; Grudt et al., 1995), these data may suggest that the 5-HT1A receptor-mediated excitation is obtained as a consequence of disfacilitation of an inhibitory input while the 5-HT2 receptor-mediated excitation is a consequence of a direct interaction with the recorded units. Within the DMV, both in vivo and in vitro recordings have shown that 5-HT2, 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptor agonists excite between 60 and 80% of DMV neurones (Albert et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1996; 1998). 5-HT1A receptor agonists, however, excited approximately 20% but inhibited around 66% of DMV neurones (Wang et al., 1995) which again may indicate presynaptic actions of 5-HT1A receptor agonists on both excitatory and inhibitory NTS neurones. Hence, these data suggest that the effects of 5-HT on the DMV depend not only on the receptor subtypes present on the DMV cell somata but also on the receptor subtypes present on the terminals of its presynaptic inputs. In addition, our laboratory has reported recently that the intrinsic properties of DMV neurones can be correlated with their target organs (Browning et al., 1999).

Unfortunately, despite the increasing evidence for a modulatory role of 5-HT in the DVC, and growing evidence pointing toward an in vivo synergistic interaction between 5-HT and TRH in the regulation of gastric acid release (Garrick et al., 1994; Yoneda & Tache, 1995), previous studies have not correlated the different responses of DVC neurones and their peripheral target or discrete NTS-DMV circuits. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to investigate the effects of 5-HT on identified DMV neurones that project to discrete areas of the GI tract.

Methods

Retrograde tracing

Sprague-Dawley rats (12 days old) of either sex were anaesthetized deeply with a 6% solution of Halothane® with air (400–600 ml min−1) in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan, U.S.A. The depth of anaesthesia (foot pinch withdrawal reflex) was assessed prior to, and during, surgery. The abdominal and thoracic areas were shaved and cleaned with 70% ethanol, and an abdominal laparotomy performed. During surgery, anaesthesia was maintained by placing the head of the rat in a custom-made anaesthetic chamber through which the halothane/air mixture was perfused. Crystals of the retrograde tracer Dil were applied to the serosal surface of the stomach (along the greater curvature of the gastric fundus and corpus, or to the antrum/pylorus) or to the intestine (the duodenum, at the level of the bifurcation of the hepatic and pancreatico-duodenal arteries, or the caecum at the level of the ileo-caecal junction). The surgical area was embedded in a fast hardening epoxy compound to prevent leakage of the retrograde tracer away from the site of application; the epoxy compound was allowed to dry (3–5 min) before the surgical area was washed with warm sterile saline solution. The wound was then sutured with 5-0 silk and the animal allowed to recover for 10–15 days.

Electrophysiology

The method utilized for the tissue slice preparation has already been described (Travagli et al., 1991). Briefly, rats were placed in a transparent, enclosed anaesthetic chamber through which Halothane® bubbled with air was passed. Once a deep level of anaesthesia was attained (abolition of the foot pinch withdrawal reflex), the rat was killed by severing the major blood vessels in the chest. The brainstem was then removed and placed in oxygenated physiological saline at 4°C (see below). Using a vibratome, six to eight coronal slices (200 μm thick) containing the DMV were cut. The slices were incubated for at least 1 h in oxygenated physiological saline at 35±1°C until use. A slice was placed in a perfusion chamber (500 μl volume), held in place by a nylon mesh and maintained at 35°C by continual perfusion with warmed oxygenated physiological saline at a rate of 2.5 ml min−1.

Prior to electrophysiological recordings, retrogradely labelled DMV neurones were identified using a Nikon E600-FS microscope equipped with DIC (Nomarski) optics and TRITC epifluorescent filters. Brief periods of illumination were used to detect the fluorescent neurones; once a labelled cell was localized, electrophysiological recordings were made under brightfield illumination using DIC optics.

Whole cell recordings were made from retrogradely labelled GI-projecting neurones only using patch pipettes filled with potassium gluconate intracellular solution of resistance 3–8 MΩ (see below) and a single electrode voltage clamp amplifier (Axoclamp 2B or Axopatch 1D, Axon Instr., Foster City, California, U.S.A.). Data were filtered at 2 kHz, digitized via a Digidata 1200C interface (Axon Instr.), acquired and stored on an IBM PC utilizing pClamp6 software (Axon Instr.). Only those recordings having a series resistance (i.e., pipette+access resistance) <15 MΩ were used. The criteria for accepting a neuronal recording included a membrane that was stable at the holding potential and which returned to baseline after action potential afterhyperpolarization as well as an action potential of at least 60 mV amplitude. Data analysis was performed using pClamp6 software.

Electrical stimulation

Tungsten electrodes (WPI Instr. Ltd. Sarasota, Florida, U.S.A.) were used to electrically stimulate the cenNTS (when recording from gastric-projecting neurones) or the comNTS (when recording from intestinal-projecting neurones). Single stimuli (0.5–1.0 ms, 10–500 μA) were applied using a Master-8 stimulator (AMPI, Jerusalem) every 20 s to evoke submaximal inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSC) of amplitude 250–550 pA.

Drug application

Drugs were applied to the bath via a series of manually operated valves. 5-HT (30 μM) was applied to all neurones to ascertain whether or not it had an effect per se before continuing with the appropriate treatments. To assess the effects of drugs, each neurone served as its own control, i.e., the results obtained after administration of a receptor agonist or antagonist were compared to those before administration using the paired t-test. Receptor agonists and antagonists were applied in concentrations demonstrated previously to be effective (Bobker & Williams, 1990; Bobker, 1994; Grudt et al., 1995). Intergroup comparisons were analysed with one-way ANOVA followed by paired t-test comparisons or with Chi Square test (χ2). Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Significance was defined as P<0.05.

Drugs and solutions

Krebs' (in mM): NaCl 126, NaHCO3 25, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2.4, NaH2PO4 1.2 and dextrose 11, maintained at pH 7.4 by bubbling with O2-CO2 (95%–5%). Intracellular solution (in mM): K-gluconate 128, KCl 10, CaCl2 0.3, MgCl2 1, HEPES 10, EGTA 1, ATP 2, GTP 0.25. Adjusted to pH 7.35 with KOH. 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DilC18(3); Dil) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oregon, U.S.A.); α-methyl 5-HT, (−)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine hydrochloride (R(−)-DOI), 8-hydroxydipropylamino-tetralin (8-OHDPAT), N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine (TFMPP), pindobind-5-HT1A, 3-tropanyl-indole-3-carboxylate hydrochloride (ICS 205-930), ketanserin tartrate and 1-(2-methoxyphenyl)-4-[4-(2-phthalminido)butyl]piperazine hydrochloride (NAN-190) were purchased from RBI (Natick, Massachusetts, U.S.A.); 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane (Halothane®) and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.).

Experimental protocols

Single action potential firing: Neurones were current clamped at a holding potential of −55 mV before injection of short (16 ms) duration depolarizing current pulses of intensity sufficient to evoke the firing of a single action potential at its offset. Following superfusion with 5-HT, DC current was injected to return the membrane potential to its pretreatment holding potential before re-running the same protocol. The duration of the action potential at threshold, the amplitude of the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) from resting potential to peak and the AHP duration (AHP-τ) from peak amplitude until it returned to baseline were measured before and after exposure to 5-HT.

IH and IKIR

To evoke IH and IKIR neurones were voltage-clamped at −50 mV and then step hyperpolarized to −120 mV in 10 mV increments before being returned to the holding potential (Travagli & Gillis, 1994).

IA

The inactivation curve for IA was constructed using 400 ms long hyperpolarizing steps from a holding potential of −50 mV in 10 mV increments to −120 mV (to remove 1A inactivation) and repolarization to −50 mV (to activate 1A).

Results

Dorsal vagal preganglionic motoneurones

Results have been obtained from a total of 206 neurones; 122 were identified as projecting to the stomach and 84 were identified as projecting to the intestine.

Electrophysiology

The basic characteristics of DMV neurones were essentially similar to those already described by this laboratory (Browning et al., 1999). Briefly, gastric neurones could be distinguished from intestinal neurones on the basic of their smaller and shorter afterhyperpolarization (19.3±1.0 mV, n=23, and 67.7±6.3 ms, n=20, vs 25.9±0.8 mV, n=16, and 109.3±27.0 ms, n=14 for gastric and intestinal neurones, respectively, P<0.05; see Figure 2), as well as localization within the DMV columns (i.e. gastric neurones in medial DMV vs intestinal neurones in lateral DMV) as well as per their fluorescent labelling.

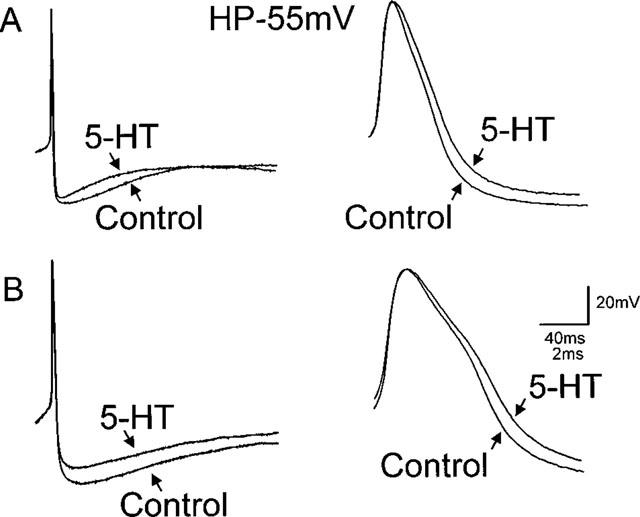

Figure 2.

5-HT decreases the duration of the action potential afterhyperpolarization and increases the action potential duration. To evoke a single action potential, neurones were current clamped at −55 mV before passing a short duration (16 ms) depolarizing current pulse of intensity sufficient to evoke the firing of one action potential at its offset. (A) Illustrate the response of a corpus-projecting neurone; (B) Illustrate the response of a caecal-projecting neurone to 5-HT (30 μM). In both gastric-projecting neurones (e.g. A) and intestinal-projecting (e.g. B) DMV neurones 5-HT decreased the amplitude of the afterhyperpolarization (left traces) as well as increasing the duration of the action potential (right traces).

Effect of 5-HT

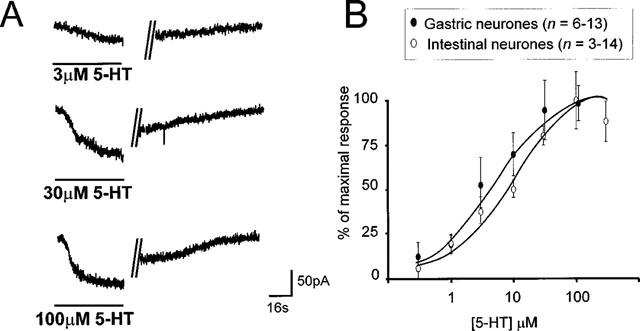

In voltage clamp experiments (Holding Potential (HP)=−50 mV), 5-HT (0.3–300 μM) was superfused for a period of time sufficient for the induced current to reach a stable plateau, generally between 60 and 150 s, depending on the depth of the neurone within the slice. Superfusion with 5-HT induced a concentration-dependent inward current in 58 out of 122 gastric projecting neurones (i.e. 47.5%) and in 58 out of 84 intestinal projecting neurones (i.e. 69%; P<0.05% vs gastric neurones). The induced inward current did not desensitize even at the highest concentrations used. The rate of onset and decay of the inward current was dependent upon the depth of the neurone within the brainstem slice but a wash out period of at least 10 min was allowed between drug applications.

While the maximum current (Imax) induced by 5-HT and the concentration that produced the maximum effect was similar for both gastric- and intestinal-projecting neurones (53.8±8.4 pA and 46.4±7.3 pA at 30 μM, for gastric and intestinal neurones, respectively, P>0.05); the EC50 was shifted rightwards in the intestinal-projecting neurones (10 μM) compared to gastric-projecting neurones (4 μM; P<0.05; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Exogenously applied 5-HT induces a concentration-dependent inward current in gastrointestinal-projecting DMV neurones. (A) Representative traces from one gastric-projecting DMV neurone illustrating the concentration-dependent nature of the inward current induced by superfusion of 5-HT. Neurones were voltage-clamped at −50 mV before application of 5-HT for a period of time sufficient for the induced current to reach a stable plateau (60–150 s). The inward current did not desensitize, even at high concentrations. The vertical lines indicate an interruption in recording of 120, 110 and 135 s for the top, middle and bottom trace, respectively. A recovery period of at least 10 min was allowed between successive applications. (B) Concentration-response curve for gastric- and intestinal-projecting DMV neurones (voltage clamped at −50 mV) in response to exogenously applied 5-HT. The current induced by 5-HT is expressed as a percentage of the maximal response. Note that the EC50 value for the inward current in intestinal neurones (10 μM) is significantly larger than that of gastric neurones (4 μM) *P<0.05.

Perfusion with 5-HT increased the duration of the action potential in both gastric- and intestinal-projecting neurones. In detail, the action potential duration in gastric-projecting neurones was increased from a control value of 2.6±0.1–2.7±0.1 ms in the presence of 5-HT (n=23; P<0.05) while in intestinal-projecting neurones, the duration of the action potential was increased from a control value of 3.0±0.2–3.3±0.3 ms in the presence of 5-HT, respectively (n=16; P<0.05; Figure 2).

Concomitant to the increase in action potential duration, perfusion with 5-HT decreased the peak amplitude of the AHP in both gastric- and intestinal-projecting neurones. In fact, 5-HT decreased the AHP in gastric-projecting neurones from 19.3±1.0 to 16.3±0.8 mV (n=23; P<0.05) while in intestinal-projecting neurones, 5-HT decreased the AHP amplitude from 25.9±0.8 to 22.1±0.7 mV (n=16; P<0.05; Figure 2).

5-HT had no effect on AHP-τ in either gastric or intestinal-projecting neurones. The AHP-τ in gastric-projecting neurones was 67.7±6.3 and 68.6±7.7 ms in control and 5-HT, respectively (n=20; P>0.05) and in intestinal-projecting neurones it was 109.3±27.0 and 87.8±16.7 ms in control and 5-HT, respectively (n=14; P>0.05).

5-HT does not affect other voltage-dependent currents (VDC)

We investigated whether 5-HT had any effect on VDC other than IAHP. We studied the non-selective cationic current IH, the fast-transient potassium current (IA) and the potassium inward rectifier (IKIR) since these currents are all present in DMV neurones (Browning et al., 1999; Travagli & Gillis, 1994) and/or they have been reported to be affected by 5-HT (Andrade & Chaput, 1991b; Bobker & Williams, 1993). Perfusion with 5-HT (30 μM) did not affect the amplitude or activation potentials of either currents (IH: −58±8 pA in control at −120 mV vs −53±7 pA in 5-HT P40.05, n=11; IKIR −235±42 pA in control at −120 mV vs −278±42 pA in 5-HT, P>0.05; n=4). Similarly, perfusion with 5-HT (30 μM) did not affect the absolute amplitude of IA (617±63 pA in control vs 602±59 pA in 5-HT, P>0.05; n=23), its activation threshold (−60 mV for both control and 5-HT), its I50 (−75 mV for both control and 5-HT) or its kinetics of decay (213±11 ms at −90 mV (see Browning et al., 1999) in control vs 220±11 ms in 5-HT, P.0.05; n=23).

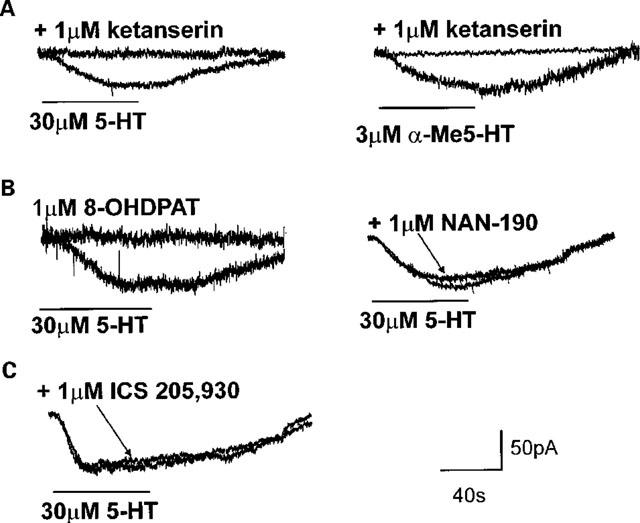

Effect of 5-HT2 receptor ligands

In eight neurones (five gastric, three intestinal) the inward current induced by perfusion with 5-HT (30 μM) was unaffected by prior perfusion with the synaptic inhibitor tetrodotoxin (30.9±2.9 pA in control vs 34.1±4.6 pA in the presence of 0.1 μM TTX, P>0.05). In ten neurones (six gastric, four intestinal), the 5-HT-induced current was mimicked by application of the 5-HT2 receptor selective agonist, α-methyl-5-HT (31.4±2.7 pA in presence of 5-HT vs 21.9±1.7 pA in the presence of 3 μM α-methyl-5-HT). Furthermore, in ten neurones (six gastric, four intestinal), the inward current induced by 30 μM 5-HT was abolished by prior perfusion with ketanserin (36.2±3.6 pA in control vs 3.22±1.1 pA in 1 μM ketanserin, P<0.05). In six neurones (three gastric, three intestinal), the inward current induced by α-Me-5-HT (3 μM) was also abolished by prior perfusion with ketanserin (20.3±2.4 pA in control vs 1.5±0.7 pA in presence of 1 μM ketanserin, P<0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The postsynaptic responses to 5-HT are mediated via activation of 5-HT2 receptors only. All neurones were voltage-clamped at −50 mV before application of 5-HT (30 μM) for periods sufficient to allow the induced inward current to reach a stable plateau. Following complete recovery and a wash-out period of at least 10 min, the response of the same neurone to 5-HT receptor selective agonists or the response to 5-HT in the presence of 5-HT receptor selective antagonists were assessed. Receptor antagonists were superfused for a minimum of 10 min before re-application of receptor agonists. (A) The inward current induced by superfusion with 5-HT (30 μM; left panel) was prevented by prior application of the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, ketanserin (1 μM). Similarly, the 5-HT2 receptor agonist α-methyl 5-HT (3 μM; black trace, right panel), mimicked the inward current induced by 5-HT, a response that was also prevented entirely by the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, ketanserin (1 μM). (B) Unlike 5-HT (30 μM; left panel), the 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-OHDPAT (1 μM) had no postsynaptic actions. Similarly, preincubation with the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, NAN-190 (1 μM, right panel) did not attenuate the 5-HT-induced inward current. (C) Preincubation with the 5-HT3/4 receptor antagonist ICS 205-930 (tropisetron, 3 μM) did not attenuate the inward current induced by 5-HT (30 μM).

In some, but not all, neurones (seven out of ten neurones; 70%) application of ketanserin (1 μM) caused an outward shift in holding current (6±2 pA, n=6) which was maintained throughout the duration of ketanserin application.

Effects of 5-HT1A receptor ligands

We also ruled out the involvement of 5-HT1A receptors in the 5-HT-induced inward current with the following experiments: in 18 neurones (eight gastric, ten intestinal) the inward current induced by 30 μM 5-HT was not mimicked by the 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-OHDPAT (34.8±3.0 pA current to 5-HT vs 2.3±0.7 pA current to 1 μM 8-OHDPAT; P<0.05) while in ten neurones (seven gastric, three intestinal) the 5-HT (30 μM) induced inward current was unaffected by prior perfusion with the 5-HT1A receptor antagonists, NAN-190 (1 μM) or pindobind-5-HT1A (1 μM) (34.8±3.5 pA in control vs 33.1±2.4 pA, P>0.05 Figure 3). Application of the 5-HT1A receptor antagonists themselves caused no change in the membrane holding current.

Effects of 5-HT3 receptor ligands

Moreover, in six neurones (three gastric, three intestinal) in which 5-HT (30 μM) induced an inward current at a holding potential of −50 mV, perfusion with the non-selective potassium current inhibitor caesium chloride (2 mM) reduced the amplitude of the 5-HT induced inward current (36.7±3.4 pA in control vs 13.7±2.9 pA in presence of CsCl, P<0.05), thus arguing in favour of an effect on a potassium-mediated conductance, as with activation of 5-HT2 receptors.

Finally, pretreatment with the 5-HT3/4 receptor antagonist ICS 205–930 (tropisetron; 3 μM did not antagonize the 5-HT induced inward current (32.2±5.7 pA in control vs 33.4±4.9 pA in the presence of ICS 205-930; n=9, six gastric, three intestinal; Figure 3). Application of ICS 205-930 alone never caused any change in the membrane holding current.

Effects of 5-HT1A/1B, 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptor ligands on the NTS evoked IPSCs

In gastric-projecting neurones, electrical stimulation of cenNTS evoked IPSC whose amplitude, duration and kinetics of decay were 405.5±23.6 pA, 413±20 ms and 171±19 mV/ms, respectively (n=44). Similarly, in intestinal-projecting neurones, electrical stimulation of comNTS evoked IPSC whose amplitude, duration and kinetics of decay were 426±28.9 pA (P>0.05 compared with gastric-projecting neurones), 487±37 ms (P<0.05 compared with gastric-projecting neurones) and 141±9 mV/ms (P>0.05 compared with gastric-projecting neurones), respectively (n=29; HP=−50 mV in both gastric and intestinal neurones). The evoked IPSCs were identified as having a GABAergic component since perfusion with the GABAA receptor antagonists bicuculline (10–30 μM; n=4) or picrotoxin (100 μM; n=2) attenuated the evoked IPSCs from a control amplitude of 400.8±86.8 pA to 95.1±41.9 pA (n=6; P<0.05).

In gastric-projecting neurones, perfusion with 5-HT (30 μM) reduced the peak amplitude of the evoked IPSC in 27 out of the 44 neurones tested (i.e. 61%) from 382.7±25.7 pA to 286.7±19.5 pA in control and 5-HT, respectively (n=27; P<0.05) with an average inhibition of control peak amplitude of 24±2% (n=27). Similarly, 5-HT reduced the duration and increased the rate of decay of the IPSC from 414±44 to 367±42 ms and 150±24 to 209±42 mV/ms, respectively (n=27, P<0.05). In intestinal-projecting neurones, perfusion with 5-HT (30 μM) reduced the peak amplitude of the evoked IPSC in 15 out of the 29 neurones tested (i.e. 52%) from 414.1±40.6 to 334.3±36.2 pA in control and 5-HT, respectively (n=15; P<0.05) with an average inhibition of the control peak amplitude of 19.1±2% (n=15; Figure 4). Similarly, 5-HT reduced the duration and increased the rate of decay of the IPSC from 487±37 to 447±37 ms and 155±17 to 166±19 mV/ms, respectively (n=15, P<0.05).

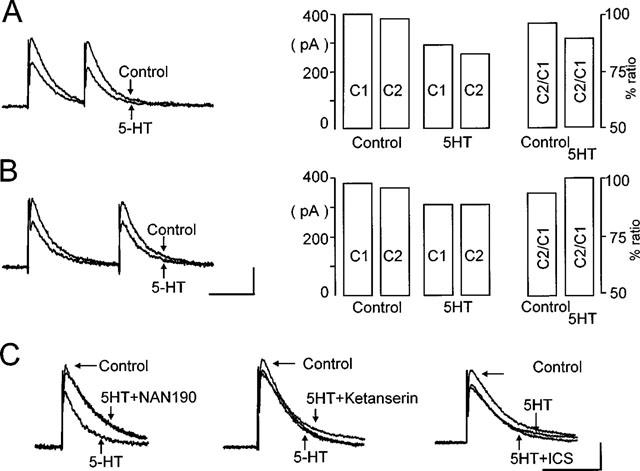

Figure 4.

Activation of presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors, decreases the amplitude of evoked IPSC. (A,B) Neurones were voltage-clamped at −50 mV before evoked IPSC were induced in gastrointestinal-projecting DMV neurones by stimulation of the NTS. Pairs of IPSC were evoked 250–750 ms apart (left panel). Following superfusion with 5-HT (30 μM), the amplitude of the evoked IPSC were reduced. This reduction in amplitude of IPSC is highlighted in the bar chart (right panel) which compares the amplitude of the first and second pulse (C1 and C2, respectively) and their ratio (C2/C1) before and after superfusion with 5-HT (30 μM). Calibration bar=400 ms, 200 pA. (C) The 5-HT-induced reduction in IPSC amplitude was attenuated by prior exposure to 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, NAN-190 (1 μM; left traces) but not by the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, ketanserin (1 μM; middle traces) or the 5-HT3/4 receptor antagonist, ICS 205-930 (tropisetron, 3 μM; right traces). Calibration bar=400 ms, 200 pA.

The ratio of the amplitude of two postsynaptic currents evoked few milliseconds apart is used to determine the pre- or postsynaptic site of drug action (Travagli & Williams, 1996; Bertolino et al., 1997). A change in the ratio is taken as an indication of a presynaptic effect.

When two IPSC were evoked 150–750 ms apart, the second IPSC (C2) was smaller than the first one (C1) in 14 out of the 27 gastric neurones responsive to 5-HT while C2 was larger than C1 in the remaining 13 neurones. When there was a decrease, the paired pulse ratio was reduced from a control value of 0.98±0.01 to 0.89±0.03 in 5-HT (n=14; P<0.05; Figure 4A). Conversely, in those which had an increase in the paired pulse ratio, its value increased from 0.97±0.01 in control to 1.01±0.01 in 5-HT (n=13; P<0.05; Figure 4B). In both instances, the alteration of the paired pulse ratio suggested a presynaptic site of action.

In intestinal-projecting neurones, the second IPSC (C2) was smaller than the first (C1) in six out of the 15 neurones responsive to 5-HT, while C2 was larger than C1 in the other nine neurones. When there was a decrease, the paired pulse ratio was reduced from 0.92±0.04 in control to 0.87±0.05 in 5-HT (n=6; P<0.05). Conversely, in those neurones that had an increase in the paired pulse ratio, its value increased from 0.96±0.01 in control to 1.00±0.01 in 5-HT (n=9; P<0.05). As for gastric neurones, the alteration of the paired pulse ratio suggested a presynaptic site of action (Figure 4).

Given that both 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors have been identified in the NTS (Thor et al., 1992a), we used receptor agonists and antagonists selective for these receptors to identify the subtype(s) involved in mediating the decrease in IPSC amplitude. The results obtained from gastric and intestinal neurones were qualitatively and quantitatively similar, i.e., they responded in a similar fashion only to challenge with 5-HT1A receptor ligands. For this reason, the data obtained from gastric and intestinal neurones have been pooled with the n specified for each subgroup.

The 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OHDPAT (1 μM) reduced the peak amplitude of the evoked IPSC from 385.2±35.2 pA to 315±33.1 pA (n=14; eight gastric and six intestinal; P<0.05). Similarly, the 5-HT1A/B receptor agonist TFMPP (1 μM) decreased the peak amplitude of the evoked IPSC from 357±39 to 276.3±28.6 pA (n=11; eight gastric and three intestinal; P<0.05). Pretreatment with the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonists NAN-190 (1 μM) or pindobind-5-HT1A (1 μM), attenuated the 5-HT (30 μM) induced inhibition of the IPSC from 22.1±2 to 0±2% (n=8; five gastric and three intestinal; P<0.05; Figure 4C). Similarly, pretreatment with NAN-190 or pindobind-5-HT1A completely prevented the inhibition by 8-OHDPAT (from 18.6±2 to 0.6±2%, P<0.05, n=6; three gastric and three intestinal) and TFMPP (from 21.3±3 to 1.2±1.8, P<0.05, n=6; three gastric and three intestinal).

5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors were not involved in the reduction of evoked IPSC since pretreatment with ICS 205-930 (3 μM, a concentration that affects both 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors) did not prevent the 5-HT mediated inhibition (418±42 and 308.8±32.2 pA in ICS 205-930 and in the presence of ICS 205-930 plus 5-HT, respectively, P<0.05; n=8, five gastric and three intestinal; Figure 4C).

Perfusion with the selective 5-HT2 receptor agonist α-methyl-5-HT (3 μM) did not significantly decrease the peak amplitude of the IPSC (444.5±70.4 pA in control and 399±63.1 pA in 3 μM α-methyl-5-HT, respectively; n=8; five gastric and three intestinal; P>0.05); the failure of 5-HT2 receptor agonists to decrease the peak amplitude of the IPSC suggests that 5-HT2 receptors do not modulate this effect.

Effects of 5-HT on spontaneous inhibitory currents (IPSCs)

Without affecting their amplitude, 5-HT (30 μM) decreased the frequency of spontaneous IPSCs in 12 out of 17 neurones and increased IPSC frequency in the remaining five neurones responsive to 5-HT. In the neurones in which 5-HT decreased the frequency of the IPSC, the frequency was reduced from 2.98±1.6 IPSC s−1 in control to 0.7±0.3 IPSC s−1 in 5-HT (P<0.05). Conversely, in those neurones in which 5-HT had an excitatory effect, the frequency increased from 3.8±3.2 to 7.1±5.1 IPSC s−1 in control and 5-HT, respectively (P<0.05). The average amplitude of IPSC was not altered by 5-HT (19.6±0.9 pA compared to 20±0.8 pA in control (n=52) and 5-HT (n=54), respectively (P>0.05). A change in the frequency of spontaneous events without a change in their amplitude has previously been shown to indicate a presynaptic site of action (Travagli & Williams, 1996).

Effects of 5-HT on spontaneous excitatory currents (EPSCs)

5-HT (30 μM) increased the frequency of spontaneous EPSC in six and decreased EPSC frequency in 12 of the 18 neurones responsive to 5-HT without affecting their amplitude. In those neurones in which 5-HT had a stimulatory effect, the frequency increased from 6.9±3.9 to 8.9±3.9 EPSC s−1 in control and 5-HT, respectively (P<0.05). Conversely, in those neurones in which 5-HT had an inhibitory effect, the frequency decreased from 6.3±0.7 to 3.2±0.6 EPSC s−1 in control and 5-HT, respectively (P<0.05). The average amplitude of the EPSC was unaltered by 5-HT (20.9±0.4 pA and 22.3±0.4 pA in control and 5-HT (n=81 for both groups), respectively (P>0.05), again suggesting a presynaptic site of action.

Discussion

With the present data we report the excitation of GI-projecting neurones of the rat DMV by 5-HT. At the postsynaptic level, 5-HT excited 69% of intestinal-projecting neurones and in 47% of gastric-projecting neurones. In both instances, the excitation was mediated via activation of 5-HT2 receptors only. At the presynaptic level, the 5-HT receptor mediated excitation of DMV neurones was achieved via disfacilitation of GABAergic inputs from NTS. The presynaptic effects were achieved via a reduction in the peak amplitude of evoked IPSCs (an effect mediated by presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors), a decrease in the frequency of spontaneous IPSCs and an increase in the frequency of EPSCs.

Postsynaptic effects of 5-HT

Recent pharmacological experiments have demonstrated that DMV neurones can be affected by interaction of 5-HT with 5-HT1A, 5-HT2, 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors (Wang et al., 1995; 1996; 1998; Yoneda & Tache, 1995; Albert et al., 1996). We used ion substitutions as well as 5-HT receptor selective agonists and antagonists to ascertain the receptor subtype(s) involved in the excitatory effects of 5-HT on identified DMV neurones.

With the present data we show that the postsynaptic response of identified DMV neurones to exogenously applied 5-HT is exclusively excitatory. This finding is in agreement with previous reports of 5-HT mediating excitation only (Travagli & Gillis, 1995; Albert et al., 1996) but it is in contrast with Wang et al. (1995), who showed an inhibition of the firing rate of DMV neurones following iontophoretic application of 8-OHDPAT or 5-HT at high currents. In our study, an outward current was not induced by perfusion with either high concentrations of 5-HT (up to 300 μM) or the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT. In addition, blockade of the 5-HT-induced inward current with the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin failed to unmask any outward current, and pretreatment with the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonists NAN-190 or pindobind-5HT1A failed to prevent 5-HT-induced effects. A plausible explanation for the conflicting results among these groups (Travagli & Gillis, 1995; Wang et al., 1995; Albert et al., 1996) is that the effects observed following application of 8-OHDPAT or high doses of 5-HT may be a consequence of their action onto the more distant NTS neurones. This hypothesis is indirectly supported by our experiments in which perfusion with 8-OHDPAT inhibited GABA-mediated currents evoked by NTS stimulation. Alternatively, it is possible that in the in vivo experiments carried out by Wang et al. (1995) there is indeed a tonic GABAergic input present that is not active in the slice preparation.

Our findings show that the postsynaptic response of identified DMV neurones to exogenously applied 5-HT is mediated by 5-HT2 receptor activation only. Our conclusion stems from the following observations: (i) the 5-HT2 receptor selective agonist α-methyl-5-HT mimicked the direct effect of 5-HT by eliciting a slow, sustained inward current; (ii) the inward current induced by both 5-HT and α-methyl-5HT was antagonized by pretreatment with the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin; (iii) the 5-HT induced inward current was neither mimicked by the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT nor attenuated by the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist NAN-190; (iv) pretreatment with ICS 205–930 at a concentration known to antagonize both 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors (Bockaert et al., 1989) did not attenuate the 5-HT induced inward current; (v) the response to 5-HT was slow in onset and did not show any desensitization; (vi) the inward current induced by 5-HT was attenuated by pretreatment with the potassium conductance inhibitor caesium; (vii) the 5-HT mediated inward current was still present in the presence of the synaptic transmission blocker tetrodotoxin.

Our conclusions that the excitatory effect of 5-HT is mediated by 5-HT2 receptors corresponds with recent in vitro reports on non-identified DMV neurones (Albert et al., 1996) as well as in vivo studies on gastrointestinal function (Yoneda & Tache, 1995; Varanasi et al., 1997). The inward current induced by 5-HT via 5-HT2 receptors would thus provide a further physiological counterpart to the studies which demonstrated a high level of 5-HT2 mRNA in the DMV (Wright et al., 1995). The finding that, in some neurones, application of the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin alone caused a maintained outward shift in holding current suggests that, in a proportion of neurones at least, 5-HT may exert a tonic modulatory role.

Our findings indicate that 5-HT excites DMV neurones directly by antagonizing the afterhyperpolarization that follows a single action potential. This decrease in the afterhyperpolarization amplitude is observed despite a significant increase in the action potential duration, suggesting a direct effect of 5-HT on the calcium-activated potassium conductance (gK-Ca) that underlies the afterhyperpolarization. Similarly, direct inhibition of gK-Ca has been observed in hippocampal neurones, although in that preparation the effect was mediated by 5-HT4 receptors (Andrade & Chaput, 1991a; Torres et al., 1996). The data showing an increase in the duration of the action potential duration would, by consequence, exclude the possibility that the 5-HT mediated reduction in the after hyperpolarization is secondary to calcium current inhibition, an effect recently reported in medullary raphe neurones by activation of 5-HT1A receptors (Bayliss et al., 1997).

In this study we report that the majority (i.e. 69%) of intestinal-projecting DMV neurones are excited by exogenous 5-HT while only 47% of gastric-projecting neurones are affected by 5-HT. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies that have investigated the effects on intestinal functions of microinjections of 5-HT in the DVC. Conversely, several lines of evidence indicate that microinjections of 5-HT (in combination with TRH) in the DVC affect mainly gastric acid secretion (McTigue et al., 1992; Krowicki & Hornby, 1995; Yoneda & Tache, 1995; Chi et al., 1996; Varanasi et al., 1997). Based on our data reporting a low percentage of DMV gastric-projecting neurones being affected by 5-HT, it is tempting to speculate that gastric-projecting DMV neurones that respond to 5-HT are indeed the ones involved in gastric-acid secretion. Should this speculation be confirmed by in vivo experiments, it would further substantiate our previously formulated hypothesis that DMV comprises heterogeneous neuronal populations that can be distinguished based on their physiological and pharmacological characteristics (Browning et al., 1999).

Presynaptic effects of 5-HT

Within the DVC, the NTS provides a robust inhibitory input into the DMV. This prompted us to investigate whether 5-HT had a modulatory effect on evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). We thus focused our attention on the inhibitory synaptic connections between the cenNTS and gastric-projecting neurones and on the connections between the comNTS and intestinal-projecting neurones. Our data suggest that the 5-HT-receptor mediated inhibition of IPSC occurs via activation of presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors. Our findings are supported by multiple lines of evidence: (i) Perfusion with 5-HT decreased the peak amplitude of the evoked outward current with a concomitant alteration of the paired pulses ratio, and modified the frequency of both spontaneous IPSC and EPSC, both indications of a decreased probability of transmitter release at the presynaptic site (Travagli & Williams, 1996; Bertolino et al., 1997; Li & Bayliss, 1998); (ii) The 5-HT1A receptor selective agonist 8-OH-DPAT mimicked the inhibition of 5-HT, in a manner similar to that described previously as a selective 5-HT1A effect (Bobker & Williams, 1993); (iii) The 5-HT receptor-mediated inhibition of the evoked IPSC was mimicked by the 5-HT1A/1B receptor agonist TFMPP, the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonists NAN-190 and pindobind-5-HT1A attenuated the effects of both 5-HT and TFMPP; (iv) perfusion with 5-HT did not alter the amplitude of spontaneous IPSCs, indicating that they did not affect postsynaptic GABA receptor sensitivity; (v) The clear pharmacological dichotomy between presynaptic (5-HT1A) and postsynaptic (5-HT2) receptors involved in the 5-HT mediated effects argues against a possible change in the passive properties of the neurones as a reason for IPSC inhibition.

Our data indicating that activation of 5-HT1A receptors in NTS decreases the inhibitory GABAergic input onto DMV neurones suggests that the increase in gastric acid secretion observed by Stephens' group upon administration of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 5-CT (in combination with TRH) might be due to presynaptic disnhiibition (Varanasi et al., 1997), a possibility we put forth recently (Travagli & Gillis, 1995).

In conclusion, our data suggest that DMV neurones are functionally non-homogenous with regard to their serotonergic modulation and indicate that the motoneurones controlling intestinal functions are more likely to be affected by 5-HT than gastric-projecting neurones.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs Renehan and Fogel for reading critically earlier versions of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIDDK grant #DK-55530 to R. Alberto Travagli.

Abbreviations

- AHP

afterhyperpolarization

- AP

action potential

- Dil

1, 1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate

- DMV

dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- HP

holding potential

- IPSC

inhibitory postsynaptic current

- NAN-190

1-(2-Methoxyphenyl)-4-[4-(2-phthalminido)butyl]piperazine hydrochloride

- NTS

nucleus of the tractus solitarius, 8-OHDPAT, 8-hydroxydipropylaminotetralin

- TFMPP

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine

References

- ALBERT A.P., SPYER K.M., BROOKS P.A. The effect of 5HT and selective 5HT receptor receptor receptor agonists and antreceptor receptor agonists on rat dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in vitro. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:519–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALTSCHULER S.M., BAO X., BIEGER D., HOPKINS D.A., MISELIS R.R. Viscerotopic representation of the upper alimentrary tract in the rat: sensory ganglia and nuclei of the solitary and spinal trigeminal tracts. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;283:248–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALTSCHULER S.M., FERENCI D.A., LYNN R.B., MISELIS R.R. Representation of the cecum in the lateral dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and commissural subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitarii in rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1991;304:261–274. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDRADE R., CHAPUT Y. 5-hydroxytryptamine 4-like receptors mediate the slow excitatory response to serotonin in the rat hippocampus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991a;257:930–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDRADE R., CHAPUT Y.The electrophysiology of serotonin receptor subtypes Sertonin receptor subtypes 1991bWilly: Liss; 103–124.In: Perout Ka, SJ (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- BAYLISS D.A., LI Y.W., TALLEY E.M. Effects of serotonin on caudal raphe neurones: inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels and the afterhyperpolarization. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1362–1374. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTOLINO M., VICINI S., GILLIS R.A., TRAVAGLI R.A. Presynaptic alpha-2 adrenoceptors inhibit excitatory synaptic transmission in rat brain stem. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:G654–G661. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.3.G654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOBKER D.H. A slow excitatory postsynaptic potential mediated by 5-HT2 receptors in nucleus prepositus hypoglossi. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:2428–2434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02428.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOBKER D.H., WILLIAMS J.T. Serotonin-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in guinea-pig prepositus hypoglossi and feedback inhibition by serotonin. J. Physiol. 1990;422:447–462. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOBKER D.H., WILLIAMS J.T. Receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine. Neurotransmitter Receptors. 1993. pp. 221–250.

- BOCKAERT J., SEBBEN M., DUMUIS A. Pharmacological characterization of 5-Hydroxytryptamine4 (5-HT4) receptors positively coupled to adenylate cyclase in adult guinea pig hippocampal membranes: effect of substituted benzamide derivatives. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1989;58:177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOOTLE D.J., ADCOCK J.J., RAMAGE A.G. The role of central 5-HT receptors in the bronchoconstriction evoked by inhaled capsaicin in anaesthetised guinea-pigs. Neuropharmacol. 1998;37:243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWNING K.N., RENEHAN W.E., TRAVAGLI R.A. Electrophysiological and morphological heterogeneity of rat dorsal vagal neurones which project to specific areas of the gastrointestinal tract. J. Physiol. 1999;517:521–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0521t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAMPAGNAT J., DENAVIT-SAUBIE M., GRANT K., SHEN K.F. Organization of synaptic transmission in the mammalian solitary complex, studied in vitro. J. Physiol. 1986;381:551–573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHI J., KEMERER J., STEPHENS R.L., Jr 5-HT in DVC: disparate effects on TRH analogue-stimulated gastric acid secretion, motility, and cytoprotection. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:R368–R372. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.2.R368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKUDA A., MINAMI T., NABEKURA J., OOMURA Y. The effects of noradrenaline on neurones in the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, in vitro. J. Physiol. 1987;393:213–231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARRICK T., PRINCE M., YANG H., OHNING G., TACHE Y. Raphe pallidus stimulation increases gastric contractility via TRH projections to the dorsal vagal complex in rats. Brain Res. 1994;636:343–347. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLIS R.A., QUEST J.A., PAGANI F.D., NORMAN W.P.Control centers in the central nervous system for regulating gastrointestinal motility Handbook of Physiology. The Gastrointestinal System. Motility and Circulation II 1989American Physiological Society: Bethesda, MD; 621–683.In: Wood, Jacki D. (ed) [Google Scholar]

- GRUDT T.J., WILLIAMS J.T., TRAVAGLI R.A. Inhibition by 5-hydroxytryptamine and noradrenaline in substantia gelatinosa of guinea-pig spinal trigeminal nucleus. J. Physiol. 1995;485:113–120. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORNBY P.J., ROSSITER C.D., WHITE R.L., NORMAN W.P., KUHN D.H., GILLIS R.A. Medullary raphe: a new site for vagally mediated stimulation of gastric motility in cats. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:G637–G647. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.258.4.G637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZZO P.N., DEUCHARS J., SPYER K.M. Localization of cardiac vagal preganglionic motoneurones in the rat: Immunocytochemical evidence of synaptic inputs containing 5-hydroxytryptamine. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;327:572–583. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROWICKI Z.K., HORNBY P.J.Hindbrain neuroactive substances controlling gastrointestinal function Regulatory mechanism in gastrointestinal function 1995Boca Raton: CRC Press Inc; 277–319.In: T.S. Gaginella (ed) [Google Scholar]

- LI Y-W., BAYLISS D.A. Presynaptic inhibiton by 5HT1B receptors of glutamatergic synaptic inputs onto serotonergic caudal raphe neurones in rat. J. Physiol. 1998;510:121–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.121bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANAKER S., VERDERAME H.M. Organization of serotonin 1A and 1B receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;301:535–553. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCANN M.J., HERMANN G.E., ROGERS R.C. Nucleus raphe obscurus (nRO) influences vagal control of gastric motility in rats. Brain Res. 1989;486:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCTIGUE D.M., ROGERS R.C., STEPHENS R.L., Jr Thyrotropin-releasing hormone analogue and serotonin interact within the dorsal vagal complex to augment gastric acid secretion. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;144:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90716-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOSJEAN A., COMPOINT C., BUISSERET-DELMAS C., ORER H.S., MERAHI N., PUIZILLOUT J.J., LAGUZZI R. Serotonergic projections from the nodose ganglia to the nucleus tractus solitarius: an immunohistochemical and double labeling study in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1990;114:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALKOVITS M., MEZEY E., ESKAY R.L., BROWNSTEIN M.J. Innervation of the nucleus of the solitary tract and the dorsal vagal nucleus by thyrotropin-releasing hormone-containing raphe neurons. Brain Res. 1986;373:246–251. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROGERS R.C., HERMANN G.E., TRAVAGLI R.A. Brainstem pathways responsible for oesophageal control of gastric motility and tone in the rat. J. Physiol. 1999;514:369–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.369ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPORTON S.C., SHEPHEARD S.L., JORDAN D., RAMAGE A.G. Microinjections of 5-HT1A agonists into the dorsal motor vagal nucleus produce a bradycardia in the atenolol-pretreated anaesthetized rat. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104:466–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEWARD L.J., WEST K.E., KILPATRICK G.J., BARNES N.M. Labelling of 5-HT3 receptor recognition sites in the rat brain using the receptor agonist radioligand [3H]meta-chlorophenylbiguanide. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;243:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90161-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SYKES R.M., SPYER K.M., IZZO P.M. Central distribution of Substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide and 5-hydroxytryptamine in vagal sensory afferents in the rat dorsal medulla. Neuroscience. 1994;59:195–210. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOR K.B., BLITZ-SIEBERT A., HELKE C.J. Autoradiographic Localization of 5-HT1 Binding Sites in the Medulla Oblongata of the Rat. Synapse. 1992a;10:185–205. doi: 10.1002/syn.890100303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOR K.B., BLITZ-SIEBERT A., HELKE C.J. Autoradiographic Localization of 5HT1 Binding Sites in Autonomic Areas of the Rat Dorsmedial Medulla Oblongata. Synapse. 1992b;10:217–227. doi: 10.1002/syn.890100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORRES G.E., ARFKEN C.L., ANDRADE R. 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptors reduce afterhyperpolarization in hippocampus by inhibiting calcium-induced calcium release. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:1316–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAVAGLI R.A., GILLIS R.A. Hyperpolarization-activated currents IH and IKIR, in rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus neurons in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1308–1317. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAVAGLI R.A., GILLIS R.A. Effects of 5-HT alone and its interaction with TRH on neurons in rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:G292–G299. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.2.G292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAVAGLI R.A., GILLIS R.A., ROSSITER C.D., VICINI S. Glutamate and GABA-mediated synaptic currents in neurones of the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:G531–G536. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.3.G531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAVAGLI R.A., WILLIAMS J.T. Endogenous monoamines inhibit glutamate transmission in the spinal trigeminal nucleus of the guinea pig. J. Physiol. 1996;491:177–185. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VARANASI S., CHI J., STEPHENS R.L. 5-CT or DOI augments TRH analog-induced gastric acid secretion at the dorsal vagal complex. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:1607–1611. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y., JONES J.F.X., RAMAGE A.G., JORDAN D. Effects of 5-HT and 5-HT1A receptor agonists and antagonists on dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in anaesthetized rats: an ionophoretic study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2291–2297. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y., RAMAGE A.G., JORDAN D. Mediation by 5-HT3 receptors of an excitatory effect of 5-HT on dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in anaesthetized rats: an ionophoretic study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1697–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y., RAMAGE A.G., JORDAN D. In vivo effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor activation on rat nucleus tractus solitarius neurones excited by vagal C-fibre afferents. Neuropharmacol. 1997;36:489–498. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y., RAMAGE A.G., JORDAN D. Presynaptic 5-HT3 receptors evoke an excitatory response in dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in anaesthetized rats. J. Physiol. 1998;509:683–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.683bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIS A., MIHALEVICH M., NEFF R.A., MENDELOWITZ D. Three types of postsynaptic glutamatergic receptors are activated in DMNX neurons upon stimulation of NTS. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:R1614–R1619. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.6.R1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT D.E., SEROOGY K.B., LUNDGREN K.H., DAVIS B.M., JENNES L. Comparative localization of serotonin1A, 1C, and 2 receptor subtype mRNAs in rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;351:357–373. doi: 10.1002/cne.903510304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YONEDA M., TACHE Y. Serotonin enhances gastric acid response to TRH analogue in dorsal vagal complex through 5-HT2 receptors in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:R1–R6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.1.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG X., FOGEL R., RENEHAN W.E. Relationships between the morphology and function of gastric- and intestine-sensitive neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;363:37–52. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]