Abstract

The walls of certain large blood vessels are nourished by the vasa vasorum, a network of microvessels that penetrate the adventitia and media of the vessel wall. The purpose of this study was to characterize endothelin-1 (ET-1)-mediated contraction of vasa and to investigate whether threshold concentrations of ET-1 alters the sensitivity to constrictors. Arterial vasa were dissected from the walls of porcine thoracic aorta and mounted in a tension myograph.

ET-1 and ETB-selective agonist, sarafotoxin 6c (S6c), produced concentration-dependent contraction. ETA receptor antagonist, BQ123 (10 μM), caused a biphasic rightward shift of ET-1 response curves. ETB receptor antagonist, BQ788 (1 μM), produced a rightward shift of response curves to ET-1 and S6c of 5- and 80 fold respectively.

ET-1 responses were abolished in Ca2+-free PSS but unaffected by selective depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Nifedipine (10 μM), an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, attenuated ET-1 responses by 44%. Inhibition of receptor-operated Ca2+ channels or non-selective cation entry using SKF 96365 (30 μM) and Ni2+ (1 mM) respectively, attenuated ET-1 contractions by 60%.

ET-1 (1–3 nM) enhanced responses to noradrenaline (NA) (4 fold) but not to thromboxane A2-mimetic, whilst K+ (10–20 mM) sensitized vasa to both types of constrictor.

Therefore, ET-1-induced contraction of isolated vasa is mediated by ETA and ETB receptors and involves Ca2+ influx through L-type and non-L-type Ca2+ channels. Furthermore elevation of basal tone of vasa vasorum alters the profile of contractile reactivity. These results suggest that ET-1 may be an important regulator of vasa vasorum reactivity.

Keywords: Endothelin, sarafotoxin, vasa vasorum, BQ123, BQ788

Introduction

Large blood vessels are nourished by diffusion of oxygen and nutrients from the lumen and also by blood flow through the vasa vasorum. The vasa vasorum forms a network of microvessels that lie predominantly in the adventitia although in certain large arteries, veins and atherosclerotic arteries these microvessels also penetrate the media (for review see Williams & Heistad, 1996). Removal of periaortic fat containing the vasa vasorum (Stefanadis et al., 1993) or occlusion of the vasa vasorum surrounding the abdominal aorta of dogs (Nakata & Shionoya, 1966) results in extensive medial necrosis and alters aortic reactivity in vivo. The application of a silastic collar to the adventitial surface of rabbit carotid arteries disrupts the vasa vasorum and induces neointima formation in the large vessel (Martin et al., 1991). These studies support the hypothesis that the vasa vasorum is important in the maintenance of homeostasis of the parent vessel and that disruption of the control of blood flow through the vasa vasorum might contribute to disease states.

Several layers of contractile smooth muscle cells are oriented radially around the vasa indicating that blood flow through these vessels may be actively regulated, but unlike the host vessel from which they are derived, these small vessels appear insensitive to potent arterial constrictors including noradrenaline (NA), thromboxane A2-mimetic (TXA2) U44069 and angiotensin II. Indeed, in our previous study, the only constrictor that produced marked contractile responses of porcine aortic vasa was endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Scotland et al., 1999), similarly, ET-1 was also the only potent constrictor of isolated human aortic vasa vasorum (Sarsero et al., 1998). These findings together with the observation that there is significant ET-1 binding in the vasa vasorum (Dashwood et al., 1993) suggests that this mediator may be particularly important in the control of flow though the vasa vasorum.

However, in certain vessels contractile responses to agonists can be potentiated in the presence of a threshold concentration of a second agonist (see for example Stupecky et al., 1986). In particular, synergy between ET-1 and several other constrictors has been reported in different vascular beds; subpressor doses of ET-1 enhance pressor responses to NA in perfused rat (Tabuchi et al., 1989; 1991) and canine (Zhang et al., 1996) small mesenteric arteries, and in human isolated arteries ET-1 potentiates contraction to NA and serotonin (Yang et al., 1990; Okatani et al., 1995). Thus overall reactivity of small blood vessels may be dependent upon the prevailing background concentrations of other constrictor agents, particularly ET-1. In the present study we have investigated the mechanisms involved in ET-1 induced contraction of isolated vasa and tested the hypothesis that threshold concentrations of ET-1 may alter the profile of reactivity of the vasa vasorum.

Methods

Porcine aorta were collected from an abattoir and placed immediately in cold (4°C) physiological salt solution (PSS) of the following composition (mM): NaCl 119, KCl 4.7, CaCl2.2H2O 2.5, MgSO4.7H2O 1.2, NaHCO3 25, KH2PO4 1.2 and glucose 5.5. Small arteries of the vasa vasorum at the adventitial-medial border were dissected out of the large vessel wall and cleaned of surrounding tissue using micro-dissection as previously described (Scotland et al., 1999).

Arteries were mounted between two stainless steel wires (40 μm in diameter) in an automated tension myograph (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) for the measurement of isometric tension (Mulvany & Halpern, 1977). Vessels were bathed in PSS gassed with 5% CO2 in O2 at 37°C. Arteries were stretched in a stepwise manner to determine the relationship between passive tension and internal circumference according to Laplace's equation. From this relationship the internal diameter was determined. Vessels were then stretched to 90% of the diameter achieved when the vessel was under an effective transmural pressure of 100 mmHg. Following the normalization procedure, vessels were contracted with high K+ (125 mM) PSS (KPSS) repeatedly until contractions were constant. Those vessels which did not produce active tension responses at least equivalent to that produced in response to an effective transmural pressure of 100 mmHg were rejected.

Characterization of contractile responses to ET-1

Receptor antagonism study

Cumulative concentration-response curves were constructed to ET-1 (0.01–300 nM) or the ETB-selective receptor agonist, sarafotoxin 6c (S6c, 0.01–30 nM) (Williams et al., 1991). To determine whether the response to ET-1 was mediated by ETA or ETB receptors some vessels were pretreated with either the selective ETA receptor antagonist BQ123 (10 μM) (Ihara et al., 1992a,1992b), the ETB receptor antagonist BQ788 (1 μM) (Ishikawa et al., 1994) or a combination of both antagonists for 30 min. Concentration-response curves were also constructed to S6c in the presence of BQ788.

Calcium mobilization

To investigate the mechanisms involved in ET-1-induced contractions vasa were pretreated with inhibitors of intracellular or extracellular Ca2+ flux, at concentrations previously shown to be maximally effective. Contractile response curves to ET-1 were constructed in the absence or presence of (i) Ca2+-free PSS containing 2 mM EGTA, (ii) L-type Ca2+-channel blocker, nifedipine (10 μM, 30 min), (iii) purported inhibitor of receptor-operated Ca2+ channel, SKF 96365 (30 μM, 30 min) (Merritt et al., 1990), or (iv) an inhibitor of non-selective cation entry, nickel (1 mM, 60 min) (Shetty & DelGrande, 1994).

To investigate the role of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, some vessels were pretreated with cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; 10 μM, 30 min), an inhibitor of sarcoplasmic reticulum CaATPase (Seidler et al., 1989). Control experiments in the absence of the antagonist or inhibitors were carried out at the same time on paired rings from the same vessel.

Potentiation of contractile responses

To investigate whether raising tone with threshold concentrations of ET-1 alters the vasoconstrictor reactivity profile of the vasa the following experiments were carried out.

Concentration-response curves were constructed to NA (1–100,000 nM) or thromboxane A2-mimetic (U44069, 0.1–1000 nM) in the absence and then in the presence of ET-1 (1–3 nM) or K+ (10–20 mM). In each case the concentration of ET-1 or K+ used was sufficient to precontract the vessel to approximately 10% of the initial KPSS response. The responses to NA and U44069 following precontraction were compared to responses to those agents in time-matched control vessels not precontracted with ET-1 or K+.

Data and statistical analysis

Contractile responses to agonists are expressed as a percentage of the response to KPSS (125 mM K+). pD2 values were calculated using non-linear regression analysis for each vessel and expressed as arithmetic mean±s.e.mean. Biphasic concentration-response curves were fitted to a modified four parameter logistic equation for two site binding using non-linear curve fitting analysis program (GraphPad Prism 2.0) to estimate two pD2 values (McLean & Coupar, 1996). Statistical significance was determined using Student t-test. For multiple comparisons one way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's test was used. Differences were considered significant when P<0.05. ‘n' represents the number of animals.

Drugs

Noradrenaline bitartrate, U44069, nifedipine, nickel sulphate and EGTA were all purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, U.K. Endothelin-1, BQ123 and BQ788 were purchased from Bachem, U.K. S6c was purchased from Novabiochem, Nottingham, U.K. Cyclopiazonic acid and SKF 96365 were purchased from Calbiochem. Noradrenaline was made in saline. Stock solutions of endothelin-1 and SKF 96365 were made in sterile water. Stock solutions of sarafotoxin 6c were made in 0.1% acetic acid. Stock solutions of U44069, BQ123, nifedipine and cyclopiazonic acid were made in DMSO. Stock solutions of BQ788 were made in 50% methanol. All stock solutions were stored frozen except SKF 96365, which was stored at room temperature. Nifedipine and noradrenaline were made on day of use. All dilutions were made in saline. The maximum concentration of DMSO or methanol in the bath at any time was 0.005% and 0.0025% respectively.

Results

The mean diameter of the vessels studied was 142.0±3.0 μm (130 vessels).

Characterization of contractile responses to ET-1

Receptor antagonism study

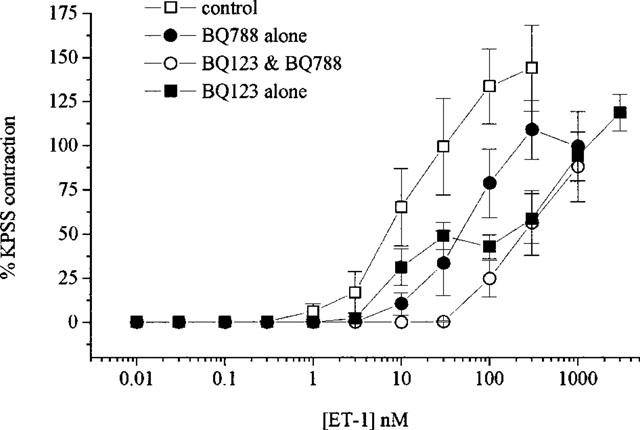

ET-1 produced slowly developing and sustained concentration-dependent contractions of isolated arterial vasa (pD2=7.8±0.1 and max. response=138.3±2.3%, n=32). Concentration-response curves to ET-1 were shifted to the right and became biphasic in the presence of BQ123 (10 μM, n=5) (see Figure 1) consisting of a high potency (pD2=8.1±0.4, max. response=54.3±4.8%) response and a low potency (pD2>5.8, max. response >120%) response.

Figure 1.

Concentration-response curves to ET-1 in the absence and presence of BQ123 (10 μM), BQ788 (1 μM) or BQ123 & BQ788. All values shown are means±s.e.mean.

BQ788 (1 μM, n=7) produced a significant (P<0.01) rightward shift (approximately 5 fold) of the ET-1 concentration-response curve (see Figure 1) giving pD2 values of 7.8±0.1 and 7.2±0.2 in the absence and presence of the antagonist respectively. Pretreatment with a combination of both receptor antagonists (n=4) produced a significant (P<0.001) rightward shift (approximately 20 fold) (see Figure 1) giving pD2 values of 7.8±0.2 and >6.4 in the absence and presence of the antagonists respectively.

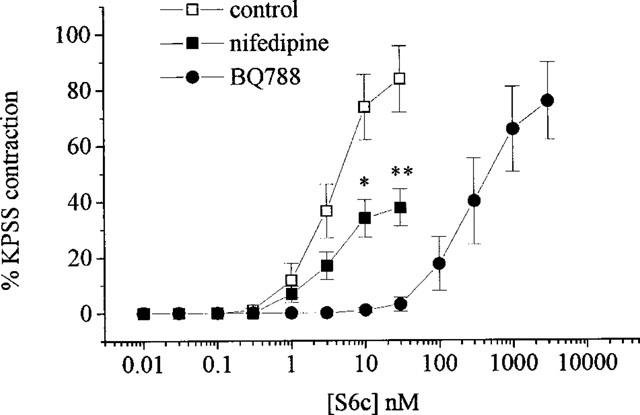

Similarly to ET-1, S6c produced potent concentration-dependent contractions (pD2=8.5±0.1 (n=7) and a maximum response of 87.4±1.6%) which were significantly (P<0.01) shifted to the right (approximately 80 fold) by BQ788 (pD2=6.5±0.1, n=6) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concentration-response curves to sarafotoxin 6c in the absence and presence of nifedipine (10 μM) or BQ788 (1 μM). All values shown are means±s.e.mean. Significance is shown as *P<0.05 or **P<0.01.

Calcium mobilization

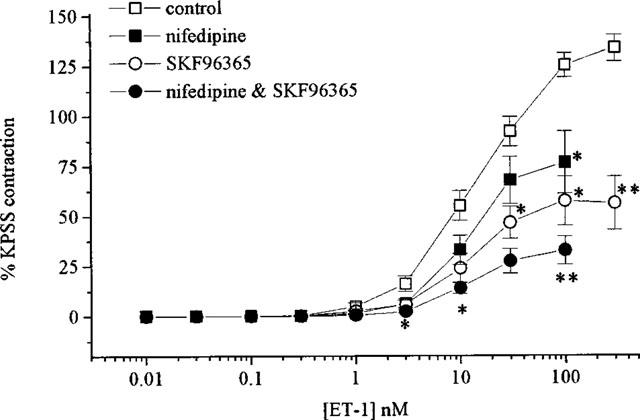

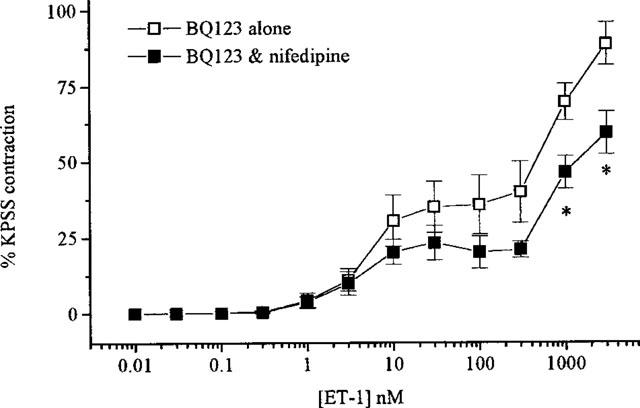

In Ca2+-free PSS the contractile response to ET-1 was abolished (n=4). In the presence of nifedipine (10 μM, n=5) ET-1 caused contractions with a maximum response approximately 44% lower than in untreated tissues but without a shift in the curve (pD2=7.6±0.1, see Figure 3). SKF 96365 (30 μM, n=5) or Ni2+ (1 mM, n=4) pretreatment attenuated ET-1-mediated contractions causing 61 and 55% suppression of the maximum response respectively (see Figure 3) and giving pD2 values of 7.7±0.1 and 7.2±0.2 in the absence and presence of Ni2+ respectively. Combination of nifedipine with SKF 96365 (n=5) had a greater effect than either inhibitor alone attenuating the maximum response to ET-1 by 75% (see Figure 3). Maximum contractions to S6c were also attenuated in the presence of nifedipine by 55% (n=7) (see Figure 2). The contractile response to ET-1 that remained following BQ123 treatment was significantly (P<0.05) suppressed by addition of nifedipine (n=7, see Figure 4) whilst that remaining following BQ788 was not. The pD2 values in the presence of BQ788 were 7.8±0.1 and 8.0±0.1 (n=5) producing maximum contractions of 135.9±16 and 110.2±20.3% in the absence and presence of nifedipine respectively (not significantly different).

Figure 3.

Concentration-response curves to ET-1 in the absence and presence of nifedipine (10 μM), SKF 96365 (30 μM) or SKF 96365 with nifedipine. All values shown are means±s.e.mean.

Figure 4.

Concentration-response curves to ET-1 in the presence of BQ123 alone or BQ123 and nifedipine. All values shown are means±s.e.mean. Significance is shown as *P<0.05.

The contractions to ET-1 were not altered in the presence of CPA (10 μM, n=5), an inhibitor of sarcoplasmic reticulum CaATPase (pD2=7.6±0.2 and 7.8±0.1 in the absence and presence of CPA respectively).

Potentiation of contractile responses

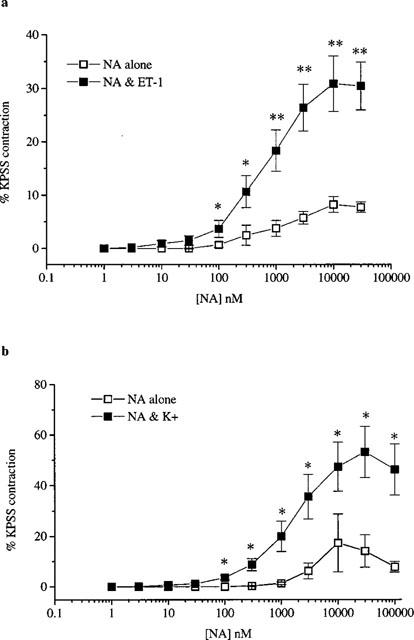

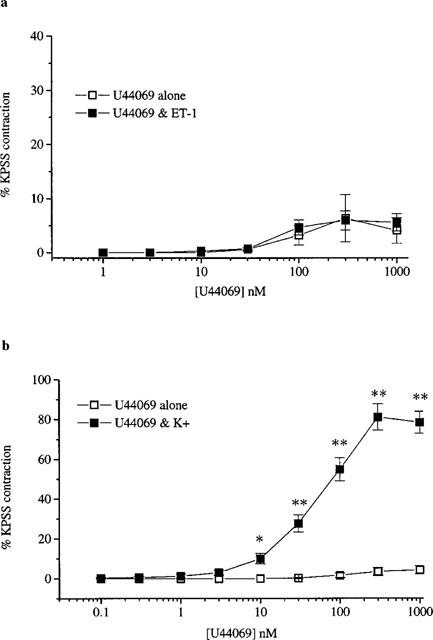

ET-1 (1–3 nM) induced contraction of 7.5±0.9% (n=11) and potentiated the responses to NA (n=7, Figure 5a) but not to U44069 (n=4, Figure 6a). Maximum responses to NA of 8.7±0.7 % and 32.1±0.8% were achieved in the absence and presence of ET-1 respectively whilst the potency of NA was not significantly altered (pD2 values of 6.0±0.2 and 6.2±0.2 in the absence and presence of ET-1 respectively). The potentiated responses to NA were blocked following pretreatment with nifedipine (n=4) but were unaffected by CPA. The pD2 values in the presence of ET-1 were 6.1±0.6 and 6.4±0.2 (n=4) in the absence and presence of CPA respectively.

Figure 5.

Responses to NA in the absence and presence of (a) ET-1 (1-3 nM) and (b) K+ (10–20 mM). All values shown are mean±s.e.mean. Significant differences between responses to ET-1 in the presence of inhibitors compared to control are shown as *P<0.05 or **P<0.01.

Figure 6.

Responses to U44069 in the absence and presence of (a) ET-1 (1-3 nM) and (b) K+ (10–20 mM). All values shown are mean±s.e.mean. Significance is shown as *P<0.05 or **P<0.01.

In contrast raising basal tone by 8.2±0.6% (n=11) using K+ (10–20 mM) significantly (P<0.01) enhanced the responses to both NA (n=6, Figure 5b) and U44069 (n=5, Figure 6b). K+-induced precontraction produced a 4 fold increase in maximum response to NA without a significant change in the pD2 values (5.6±0.5 in the absence and 5.8±0.2 in the presence of K+). In the absence of K+ U44069 had no contractile effect but in the presence of K+ the TXA2-mimetic produced potent concentration-dependent contraction with a pD2 of 7.2±0.1 and a maximum effect of 83.6±3.8%. The potentiated response to U44069 was unaffected by pretreatment with CPA (n=7). The pD2 values in the presence of K+ were 7.0±0.2 (n=6) in the absence and presence of CPA.

Discussion

ET-1 is a potent constrictor of arterial vasa isolated from porcine aorta. The results of this study indicate that the contractions are mediated by two receptor subtypes and involve the influx of calcium through L-type and non-L-type Ca2+ channels. Furthermore low concentrations of ET-1 enhance the contractile responses to NA.

Characterization of contractile responses to ET-1

Receptor antagonism study

Contraction of vascular smooth muscle to ET-1 is mediated by at least two distinct receptor subtypes: ETA and ETB. The distribution of receptor subtype and the contribution that they make to ET-1-induced contraction varies between vascular beds (for review see Bax & Saxena, 1994). In the present study ET-1 contracted isolated porcine vasa with a pD2 similar to that reported in other porcine small arteries (Awane-Igata et al., 1997) and human small arteries (Pierre & Davenport, 1998), and the contractile response to ET-1 was mediated by both ETA and ETB receptors.

Blockade of ETB receptors using the selective ETB antagonist BQ788 significantly shifted the ET-1 response curve to the right indicating that ETB receptors mediate at least part of the ET-1 induced contraction of vasa. Confirmation of the presence of ETB receptors was provided by the demonstration that S6c, the selective ETB agonist, produced potent concentration-dependent contraction that was significantly shifted to the right by BQ788. Blockade of ETA receptors, using the selective ETA antagonist BQ123, also shifted the concentration-response curve to ET-1 to the right demonstrating that ETA receptors are involved in ET-1 induced contractions. The response to ET-1 became biphasic in the presence of BQ123, such that responses to high concentrations of ET-1 were shifted to the right whilst the response to low concentrations were BQ123-resistant. Similar sensitivity to BQ123 has also been reported in other small resistance arteries (Mickley et al., 1997). The persisting ET-1-induced contraction in the presence of ETA antagonism, which was of a comparable magnitude to that to S6c, may be ETB-mediated since BQ788 abolished the BQ123-resistant component of the ET-1 response. Combined blockade of ETA and ETB receptors resulted in a parallel monophasic shift of the concentration-response curve. Curiously, however this shift did not equate to an additive effect of BQ123 and BQ788, since the shift of the ET-1 curve was no greater than the effect of BQ123 alone on the upper portion of the response curve. The reasons for this anomally are unclear but are consistent with a permissive role of ETB in mediation of ET-1 contraction at the higher concentrations although further studies are required to test this hypothesis. Nevertheless, our results indicate that in the vasa vasorum of the porcine aorta ET-1-induced contraction is produced by activation of both ETA and ETB receptors.

Calcium mobilization

The mechanisms of ET-1-stimulated Ca2+ influx have been studied extensively (for review see Decker & Brock, 1998) but the results are contradictory. The contractile response of the vasa vasorum to ET-1 is clearly dependent on Ca2+ entry since bathing the vessels in a Ca2+-free solution abolished the response, whereas depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with CPA had no effect. Our results indicate that voltage-gated and receptor-operated Ca2+ channels are important in mediating the Ca2+ entry in response to ET-1 in these vessels.

In untreated vessels ET-1 produced slowly developing, sustained contractions which were attenuated in the presence of nifedipine, an inhibitor of L-type Ca2+ channels. Other studies have suggested that ET-1 causes a biphasic increase in intracellular Ca2+ in vascular smooth muscle (Somlyo & Somlyo, 1994), suggesting the involvement of at least two different mechanisms of calcium mobilization. To test whether ET-1 stimulates an increase in Ca2+ through non-L-type channels we explored the effects of agents that block Ca2+ entry through receptor-operated channels. SKF 96365, a purported inhibitor of receptor-operated Ca2+ channels (Merritt et al., 1990), inhibited contractions to ET-1 by about 50%. Ni2+, a non-selective inhibitor of cation entry (Shetty & DelGrande, 1994), produced a similar inhibition of ET-1-induced contractions. Combination of nifedipine with SKF 96365 produced almost complete blockade of ET-1 responses supporting a role for nifedipine-insensitive channels in mediating the responses to ET-1.

Since both BQ123 and BQ788 modified ET-1-induced contractions we investigated the possibility that the activation of two distinct Ca2+ mobilization pathways reflects the activation of two distinct receptors. Contractions to the selective ETB agonist S6c were partially inhibited following pretreatment with nifedipine whilst ET-1-induced contractions seen in the presence of ETB antagonism were resistant to nifedipine. These findings would be consistent with the possibility that in porcine vasa vasorum ETB receptors are coupled to voltage-sensitive L-type channels whilst the ETA-mediated component of ET-1 contractions is likely to be predominantly due to influx of Ca2+ through non-L-type channels. However, in the presence of BQ123 nifedipine suppressed both phases of the resulting contractions and further studies are required to determine the mechanisms of Ca2+ mobilization following ETA or ETB activation in these vessels.

Potentiation of contractile responses

ET-1 not only produced potent contraction but also sensitized arterial vasa to the constrictor effects of NA such that in the presence of ET-1 the maximum contraction to NA increased 4 fold. Similar ET-1-induced enhancement of contractile responses to α-adrenergic agonists or adrenergic nerve stimulation has been reported in rat (Tabuchi et al., 1989; 1991), and canine (Zhang et al., 1996) isolated mesenteric arteries. Nifedipine abolished ET-1-induced potentiation of NA responses implicating influx of extracellular Ca2+ through L-type channels in mediation of this enhanced response to NA. Similar effects of inhibition of L-type channels have been seen in human internal mammary arteries (Yang et al., 1990) and perfused rat mesenteric arteries (Tabuchi et al., 1989). In contrast to its effects on NA-induced contractions, ET-1 did not potentiate responses to U44069. However, depolarization of smooth muscle with K+, which would also be expected to open voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, significantly potentiated the responses to both NA and TXA2-mimetic. The reasons for the differences in potentiation of responses by ET-1 or K+ are not clear. Both stimuli increased basal tension to the same degree (10%) and both would be expected to open voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Further studies will be needed to explore the mechanisms underlying these differential responses.

Clinical significance

The finding that low levels of ET-1 alters the responses to NA may be of considerable physiological and pathophysiological importance. The isolated vasa vasorum is normally resistant to NA-induced contraction and we have argued previously that this might be important to allow maintenance of vessel wall perfusion when the host conduit vessel is contracting to sympathetic stimulation (Scotland et al., 1999). Our present findings suggest that an increase in ET-1 levels would expose reactivity to NA and that depolarization would enhance responses to both NA and TXA2, which may be released from platelets.

Circulating plasma levels of ET-1 are elevated in several diseases including atherosclerosis, hypertension, congestive heart failure, asthma and diabetes (for review see Brooks et al., 1998). Furthermore, radioimmunoassay studies have demonstrated a significant increase in endogenous ET in human aorta with atheromatous plaques (Bacon et al., 1996). ET-1 synthesis (Bodi et al., 1995) and release in both resistance (Rakugi et al., 1990) and conduit (Pape et al., 1997) vessels can also be stimulated by hypoxia or thrombin (Marsen et al., 1995). Hypoxia may also lead to depolarization through inhibition of K+ channels (Grote et al., 1988; Yuan et al., 1993). The results of our study suggest therefore that various pathophysiological states might significantly alter the reactivity of the vasa vasorum which in turn may lead to underperfusion of the host vessel wall. In this respect endothelin receptor antagonists might have useful effects to preserve or restore patency of the vasa vasorum.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the porcine vasa vasorum contracts to ET-1. This contraction is mediated by ETA and ETB receptors and involves the influx of Ca2+ through L-type and non-L-type channels. Furthermore threshold concentrations of ET-1 alter the reactivity of vasa to NA. Together our findings suggest that ET-1 may have an important role in the regulation and modulation of nutrient blood flow through the vasa vasorum.

Acknowledgments

A. Ahluwalia is the recipient of an intermediate BHF Fellowship and R. Scotland is funded by an MRC studentship.

Abbreviations

- BQ123

Cyclo(-D-Trp-D-Asp-Pro-D-Val-Leu)

- BQ788

N-cis-2,6-dimethylpiperidinocarbonyl-β-tBu-Ala-D-Trp(1-methoxycarbonyl)-D-Nle-OH

- CPA

cyclopiazonic acid

- EGTA

ethyleneglycol-bis-(β-aminoethyl-ether)-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- KPSS

125 mM K+ equimolar substitution for Na+ in physiological salt solution

- NA

noradrenaline

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- SKF 96365

1-{β-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]-4-methoxyphenethyl}-1H-imidazole hydrochloride

- S6c

sarafotoxin 6c

- TXA2

thromboxane A2

- U44069

9,11-Dideoxy-9α, 11α-epoxy-methano prostaglandin F2α

References

- AWANE-IGATA Y., IKEDA S., WATANABE T. Inhibitory effects of TAK-044 on endothelin induced vasoconstriction in various canine arteries and porcine coronary arteries: a comparison with selective ETA and ETB receptor antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:516–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BACON C.R., CAREY N.R., DAVENPORT A.P. Endothelin peptide and receptors in human atherosclerotic coronary artery and aorta. Circ. Res. 1996;79:794–801. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAX W.A., SAXENA P.R. The current endothelin receptor classification: time for reconsideration. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BODI I., BISHOPRIC N.H., DISCHER D.J., WU X., WEBSTER K.A. Cell-specificity and signaling pathway of endothelin-1 gene regulation by hypoxia. Cardiovasc. Res. 1995;30:975–984. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(95)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS D.P., JORKASKY D.K., FREED M.I., OHLSTEIN E.H.Pathophysiological role of endothelin and potential therapeutic targets for receptor antagonists Endothelin: Molecular Biology, Physiology, and Pathophysiology 1998Totowa: NJ; 223–268.In: Highsmith, R.F. (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- DASHWOOD M.R., BARKER S.G.E., MUDDLE J.R., YACOUB M.H., MARTIN J.F. 125-ET-1 binding to the vasa vasorum and regions of neovasclarization in human and porcine blood vessels: a possible role for endothelin in intimal hyperplasia and atherosclerosis. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 1993;8:S343–S347. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199322008-00090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DECKER E.R., BROCK T.A.Endothelin receptor-signaling mechanisms in vascular smooth muscle Endothelin: Molecular Biology, Physiology, and Pathophysiology 1998Totowa: NJ; 93–119.In: Highsmith R.F., (ed) [Google Scholar]

- GROTE J., SIEGEL G., ZIMMER K., ADLER A. The influence of oxygen tension on membrane potential and tone of canine carotid artery smooth muscle. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1988;222:481–487. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9510-6_57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IHARA M., ISHIKAWA K., FUKURODA T., SAEKI T., FUNABASHI K., FUKAMI T., SUDA H., YANO M. In vitro biological profile of a highly potent novel endothelin (ET) antagonist BQ-123 selective for the ETA receptor. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1992a;20 Suppl 12:S11–S14. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199204002-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IHARA M., NOGUCHI K., SAEKI T., FUKURODA T., TSUCHIDA S., KIMURA S., FUKAMI T., ISHIKAWA K., NISHIKIBE M., YANO M. Biological profiles of highly potent novel endothelin antagonists selective for the ETA receptor. Life Sci. 1992b;50:247–255. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90331-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIKAWA K., IHARA M., NOGUCHI K., MASE T., MINO N., SAEKI T., FUKURODA T., FUKAMI T., OZAKI S., NAGASE T. Biochemical and pharmacological profile of a potent and selective endothelin B-receptor antagonist, BQ-788. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSEN T.A., SIMONSON M.S., DUNN M.J. Thrombin induces the preproendothelinl gene in endothelial cells by a protein tyrosine kinase-linked mechanism. Circ. Res. 1995;76:987–995. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN J.F., BOOTH R.F.G., MONCADA S. Arterial wall hypoxia following thrombosis of the vasa vasorum is an initial lesion in atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 1991;21:355–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1991.tb01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLEAN P.G., COUPAR I.M. Characterisation of a postjunctional 5-ht7-like and a prejunctional 5-HT3 receptor mediating contraction of rat isolated jejunum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;312:215–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERRITT J.E., ARMSTRONG W.P., BENHAM C.D., HALLAM T.J., JACOB R., JAXA-CHAMIEC A., LEIGH B.K., MCCARTHY S.A., MOORES K.E., RINK T.J. SK&F 96365, a novel inhibitor of receptor-mediated calcium entry. Biochem. J. 1990;271:515–522. doi: 10.1042/bj2710515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICKLEY E.J., GRAY G.A., WEBB D.J. Activation of endothelin ETA receptors masks the constrictor role of endothelin ETB receptors in rat isolated small mesenteric arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULVANY M.J., HALPERN W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circ. Res. 1977;41:19–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKATA Y., SHIONOYA S. Vascular lesions due to obstruction of the vasa vasorum. Nature. 1966;212:1258–1259. doi: 10.1038/2121258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKATANI Y., TANIGUCHI K., SAGARA Y. Amplifying effect of endothelin-1 on serotonin-induced vasoconstriction of human umbilical artery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995;172:1240–1245. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAPE D., BEUCHARD J., GUILLO P., ALLAIN H., BELLISSANT E. Hypoxic contractile response in isolated rat thoracic aorta: role of endothelium, extracellular calcium and endothelin. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1997;11:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1997.tb00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIERRE L.N., DAVENPORT A.P. Endothelin receptor subtypes and their functional relevance in human small coronary arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:499–506. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAKUGI H., TABUCHI Y., NAKAMARU M., NAGANO M., HIGASHIMORI K., MIKAMI H., OGIHARA T. Evidence for endothelin-1 release from resistance vessels of rats in response to hypoxia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1990;169:973–977. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91989-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARSERO D., FUJIWARA T., MOLENAAR P., ANGUS J.A. Human vascular to cardiac tissue selectivity of L- and T-type calcium channel antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:109–119. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCOTLAND R., VALLANCE P., AHLUWALIA A. On the regulation of tone in vasa vasorum. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;41:237–245. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEIDLER N.W., JONA I., VEGH M., MARTONOSI A. Cyclopiazonic acid is a specific inhibitor of the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:17816–17823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHETTY S.S., DELGRANDE D. Inhibition by nickel of endothelin-1-induced tension and associated 45Ca movements in rabbit aorta. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:1223–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMLYO A.P., SOMLYO A.V. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature. 1994;372:231–236. doi: 10.1038/372231a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEFANADIS C.I., KARAYANNACOS P.E., BOUDOUAS H.K., STRATOS C.G., VLACHOPOULOS C.V., DONTAS I.A., TOUTOUZAS P.K. Medial necrosis and acute alterations in aortic distensibility following removal of the vasa vasorum of canine ascending aorta. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:951–956. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.6.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STUPECKY G.L., MURRAY D.L., PURDY R.E. Vasoconstrictor threshold synergism and potentiation in the rabbit isolated thoracic aorta. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1986;238:802–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TABUCHI Y., NAKAMARU M., RAKUGI H., NAGANO M., OGIHARA T. Endothelin enhances adrenergic vasoconstriction in prefused rat mesenteric arteries. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1989;159:1304–1308. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TABUCHI Y., SHI S., MIKAMI H., OGIHARA T. Endothelin modulates L-N-Nitroarginine-induced enhancement of vasoconstriction evoked by norepinephrine. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 1991;17:S203–S205. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199100177-00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS D.L., JR, JONES K.L., PETTIBONE D.J., LIS E.V., CLINESCHMIDT B.V. Sarafotoxin S6c: an agonist which distinguishes between endothelin receptor subtypes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;175:556–561. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS J.K., HEISTAD D.D. Structure and function of vasa vasorum. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1996;6:53–57. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(96)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG Z.H., RICHARD V., VON SEGESSER L., BAUER E., STULZ P., TURINA M., LUSCHER T.F. Threshold concentrations of endothelin-1 potentiate contractions to norepinephrine and serotonin in human arteries. A new mechanism of vasospasm. Circulation. 1990;82:188–195. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YUAN X., GOLDMAN W.F., TOD M.L., RUBIN L.J., BLAUSTEIN M.P. Hypoxia reduces potassium currents in cultured rat pulmonary but not mesenteric arterial myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:L116–L123. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.2.L116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG J., OKAMURA T., TODA N. Pre- and postjunctional modulation by endothelin-1 of the adrenergic neurogenic response in canine mesenteric arteries. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;311:169–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]