Abstract

To determine the putative contribution of KATP-channels to the haemodynamic sequelae of endotoxaemia, three experiments were carried out in different groups of conscious, chronically-instrumented, unrestrained, male Long Evans rats.

In the first experiment, pretreatment with the KATP-channel antagonist, glibenclamide, abolished the initial hypotension, but not the renal vasodilatation caused by LPS infusion. Subsequently, however, in the presence of glibenclamide and LPS there was a significant increase in mean arterial blood pressure, and a bradycardia, in contrast to the fall in mean arterial blood pressure and the tachycardia seen in the presence of vehicle and LPS. The pressor and bradycardic changes in the presence of glibenclamide and LPS were accompanied by significant reductions in hindquarters flow and vascular conductance, and these were significantly greater than those seen in the presence of vehicle and LPS, or glibenclamide and saline.

Administration of glibenclamide 6 h after the onset of saline and LPS infusion, or 6 h after the onset of saline and LPS infusion in the presence of the AT1-receptor antagonist, losartan, and the ETA-, ETB- receptor antagonist, SB 209670, in the absence or presence of dexamethasone, caused a significant increase in mean arterial blood pressure and reductions in renal, mesenteric and hindquarters conductances, although the latter was the only vascular bed in which there was a reduction in flow.

The results are consistent with a contribution from KATP-channels to the vasodilatation caused by LPS, particularly in the hindquarters vascular bed.

Keywords: KATP-channels, glibenclamide, vasodilatation, lipopolysaccharide

Introduction

The cardiovascular sequelae of endotoxaemia are complex, but are often viewed simplistically. Thus, dogma has it that there is widespread vasodilatation in the endotoxaemic state, due both to increased production of nitric oxide (NO) (Rees et al., 1990; Julou-Schaeffer et al., 1990; see Kilbourn et al., (1997) for review) and to diminished sensitivity to endogenous vasoconstrictor agents (e.g., Schaller et al., 1985; Guc et al., 1990; Szabo et al., 1993; Waller et al., 1994). While the evidence for elevated production of NO and diminished vasoconstrictor sensitivity is solid, the occurrence of vasodilatation has often been inferred from the fall in blood pressure, usually seen in response to bolus injection of lipopolysaccharide in anaesthetized rats (e.g., Thiemermann & Vane, 1990). In this context it is notable that, following bolus injection of LPS in conscious rats, the early, marked hypotension occurs in the absence of renal, mesenteric or hindquarters vasodilatation, and is, therefore, likely due to a fall in cardiac output (Gardiner et al., 1998b). Moreover, during infusion of LPS in conscious rats, although regional vasodilatations occur, they are regionally selective and vary through time (Gardiner et al., 1995). This is probably because, in vivo, vasoconstrictors such as angiotensin II, endothelin, and vasopressin exert substantial effects (Gardiner et al., 1996c), opposing the vasodilator action of NO, which is particularly prominent about 6 h (Gardiner et al., 1995). However, following treatment with SB 209670 (an ETA-, ETB-receptor antagonist), and dexamethasone (to suppress inducible NO synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 induction), there is still prominent vasodilatation in the renal, hindquarters and, particularly, mesenteric vascular bed around 6–8 h after the onset of LPS infusion (Gardiner et al., 1996a). It appears that adrenomedullin is not responsible for this vasodilatation, although there may be a small contribution from calcitonin gene-related peptide (Gardiner et al., 1998a; 1999c).

Studies in other models of endotoxaemia have raised the possibility that KATP-channels contribute to the hypotensive effects of LPS (e.g., Landry & Oliver, 1992; Vanelli et al., 1995; Wu et al., 1995), but none have considered the in vivo regional vascular influence of antagonising KATP-channels in the endotoxaemic state, although Vanelli et al. (1995) have excluded a contribution from increased cardiac output to the pressor effect of glibenclamide (at least in anaesthetized, endotoxaemic pigs pre-treated with indomethacin). Previous experiments have indicated that inhibition of KATP-channels with glibenclamide can have pressor and regional vasoconstrictor effects in conscious, normal rats (see Gardiner et al., 1996d). However, there is no concensus regarding the involvement of KATP-channels in the maintenance of resting cardiovascular status based on in vivo responses to glibenclamide, and relatively little information is available regarding the distribution of KATP-channels within the vasculature (see Challinor-Rogers & McPherson, 1994, for review). Therefore, our first objective was to assess the regional haemodynamic effects of pretreatment with glibenclamide on responses to LPS. We detected an apparent effect of glibenclamide in this protocol (see Results), but this could have been due to suppression of the expression of iNOS (Wu et al., 1995). For this reason, in another experiment, we gave glibenclamide 6 h after the onset of LPS in the presence of SB 209670 and losartan, when vasodilator responses and iNOS activity are maximal (see above). Since glibenclamide does not affect iNOS activity (Wu et al., 1995), any action it exerted under these conditions would more likely be due to inhibition of KATP-channels. However, insulin release by glibenclamide might have suppressed NO production, since insulin has been shown to have a similar effect to dexamethasone in reducing skeletal muscle NO production, although not by suppression of iNOS gene transcription (Bédard et al., 1998). Therefore, in a third experiment, we assessed the regional haemodynamic effects of glibenclamide administered 6 h after the onset of LPS infusion in the presence of dexamethasone, SB 209670 and losartan, i.e., under conditions in which the vasodilatation was not likely to be due to increased NO production. Some of the results herein have been presented to the British Pharmacological Society (Gardiner et al., 1997; 1999a).

Methods

Male, Long Evans rats (350–450 g) were used in all experiments. Under anaesthesia (sodium methohexitone (Brietal, Lilly), 40–60 mg kg−1 i.p.) pulsed Doppler probes were implanted around the left renal and superior mesenteric arteries, and the distal abdominal aorta (to monitor hindquarters flow). At least 7 days later animals were anaesthetized again (as above) for the implantation of intra-arterial and intravenous catheters; all procedures have been described in detail previously (Gardiner et al., 1995; 1998b).

At least 1 day after catheterization, while animals were conscious, unrestrained, and with free access to food and water, the following experimental protocols were run.

Cardiovascular changes during LPS infusion after glibenclamide pretreatment

In a previous study we found that it was necessary to give glibenclamide at a dose of 20 mg kg−1 to achieve substantial inhibition of the cardiovascular effects of an infusion (5 μg kg−1 min−1) of the KATP-channel agonist, levcromakalim (Gardiner et al., 1996d). Therefore, glibenclamide (solubilized in 1% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin) was infused over 4 min at a rate of 1 ml min−1 to give a total dose of 20 mg kg−1, 15 min before the onset of LPS infusion (150 μg kg−1 h−1) for 5 h in eight rats.

As controls for this experiment, animals (n=8) were pretreated with vehicle and then infused with LPS, or were pretreated with glibenclamide (as above) and then infused with saline (n=7).

Cardiovascular responses to glibenclamide after the onset of LPS infusion

Since the effects of pretreatment with glibenclamide could have been due to inhibition of iNOS expression (see Introduction), further experiments were performed to assess the influence of delayed treatment with glibenclamide. In a group of rats (n=9) LPS infusion was begun 1 h after the onset of saline infusion (as a control for experiments below) and continued for 6 h before glibenclamide was administered (as above). This time point was chosen because it was when maximal iNOS activity is seen in this model of endotoxaemia (Gardiner et al., 1995) and the effects of pretreatment with glibenclamide were most apparent (see Results).

Cardiovascular responses to glibenclamide after the onset of LPS infusion in the presence of losartan and SB 209670, with or without dexamethasone

Rats (n=9 in each group) were given losartan (10 mg kg−1) (Batin et al., 1991) and the ETA-, ETB-receptor antagonist, SB 209670 (300 μg kg−1 bolus, 300 μg kg−1 h−1, infusion; Gardiner et al., 1996a), or losartan and SB 209670 and dexamethasone (12.5 μg kg−1 h−1; Gardiner et al., 1996a) 1 h before the onset of LPS infusion (as above), with glibenclamide being infused (as above) 6 h after the onset of LPS infusion.

As controls for these experiments, animals pretreated with losartan and SB 209670 with (n=6) or without (n=8) dexamethasone (as above) were infused with saline for 6 h before glibenclamide was administered. Other animals (n=6 in each group) pretreated with losartan and SB 209670, with or without dexamethasone, were infused with LPS for 6 h before vehicle was administered.

In selected experiments blood glucose levels were measured (Reflolux S, Boehringer). In those protocols involving pretreatment with glibenclamide or vehicle, blood samples were taken immediately before and 5 h after administration of glibenclamide or vehicle. When glibenclamide or vehicle was given during infusion of LPS or saline, blood samples were taken immediately before and 1 h after administration of glibenclamide or vehicle (i.e., at the end of the experiment).

Data analysis

Recordings of mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), instantaneous heart rate and renal, mesenteric and hindquarters Doppler shift signals were made for 30 min before and continuously for the first 2 h of the experiment, and thereafter at each hour until 5–6 h into the infusion of LPS or saline, when recordings were again made continuously for the following hour in those experiments in which glibenclamide or vehicle were given as post-treatments.

Within-group analysis was by Friedman's test and between-group analyses by the Kruskal-Wallis test; a P value <0.05 was taken as significant.

Materials

LPS (E. coli serotype 0127 B8), glibenclamide and dexamethasone (water soluble) were obtained from Sigma (U.K.). Losartan potassium was a gift from Dr R.D. Smith (Du Pont, U.S.A.) and SB 209670 ([(−)-(1S,2R,3S)-3-(2-carboxy-methoxy-4-meth-oxyphenyl)- 1- (3,4-methylene - dioxyphenyl)- 5-(-prop-1-yloxy)indane-2-carboxylic acid]) was a gift from Dr E. Ohlstein (SKB, U.S.A.). All substances were dissolved in sterile, isotonic saline (NaCl 154 mmol l−1) with the exception of glibenclamide which was solubilized in 1% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin in 5% dextrose. All infusions were given at 0.4 ml h−1 and bolus injections were given in 0.1 ml, flushed in with 0.1 ml.

Results

Cardiovascular changes during LPS infusion after glibenclamide

In the three groups in this experiment, resting values were: heart rate: 331±8, 318±10, and 322±7 beats min−1; MAP: 102±2, 105±2, and 106±2 mmHg; renal Doppler shift: 5.8±0.4, 5.7±0.4, and 4.9±0.3 kHz; mesenteric Doppler shift: 6.9±0.8, 5.7±0.6, and 5.7±0.4 kHz; hindquarters Doppler shift: 3.5±0.2, 3.7±0.3, and 3.9±0.5 kHz; renal vascular conductance: 56±4, 54±4, and 47±3 (kHz mmHg−1)103; mesenteric vascular conductance: 68±7, 55±6, and 54±5 (kHz mmHg−1)103; hindquarters vascular conductance: 35±2, 35±3, and 37±5 (kHz mmHg−1)103.

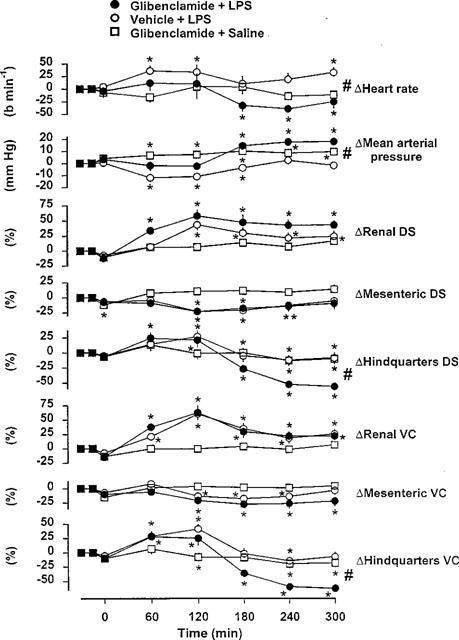

Glibenclamide had an initial pressor effect, accompanied by variable haemodynamic changes (data not shown), but by 15 min after the onset of its administration these effects had waned (Figure 1). However, following glibenclamide pretreatment, LPS infusion caused a slow-onset increase in MAP accompanied by bradycardia (Figure 1). Renal flow and vascular conductance showed early-onset, persistent increases, whereas mesenteric flow and vascular conductance were decreased (Figure 1). Following initial increases in hindquarters flow and vascular conductance, these variables showed significant reductions, coincident with the rise in MAP (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular changes in conscious Long Evans rats following pretreatment with glibenclamide and infused with LPS for 5 h (n=8), or following pretreatment with vehicle and infused with LPS for 5 h (n=8), or following pretreatment with glibenclamide and infused with saline for 5 h (n=7). Values are mean and vertical bars are s.e.mean. *P<0.05 versus original baseline (Friedman's test); #P<0.05 between changes (at 300 min) in the presence of vehicle and LPS versus changes in the presence of glibenclamide and LPS (Kruskal-Wallis test); DS=Doppler shift; VC=vascular conductance.

During infusion of LPS after vehicle pretreatment, there was an initial fall in MAP accompanied by increases in heart rate and renal and hindquarters flows and vascular conductances (Figure 1). Subsequently, however, there was no bradycardia or increase in MAP, in contrast to the changes seen in the presence of glibenclamide. Moreover, the reductions in hindquarters flow and vascular conductance were significantly less in the presence of vehicle and LPS (Kruskal-Wallis test) (Figure 1). These differences were likely due to an interaction between the effects of glibenclamide and LPS, since cardiovascular changes during saline infusion after glibenclamide pretreatment were slight (Figure 1).

Cardiovascular responses to glibenclamide after the onset of LPS infusion

In the group in this experiment, resting values were:- heart rate: 326±9 beats min−1; MAP: 105±2 mmHg; renal, mesenteric and hindquarters Doppler shift: 8.7±0.6, 8.3±0.4, and 4.4±0.3 kHz, respectively; renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vascular conductance: 84±5, 80±3, and 42±3 (kHz mmHg−1)103, respectively.

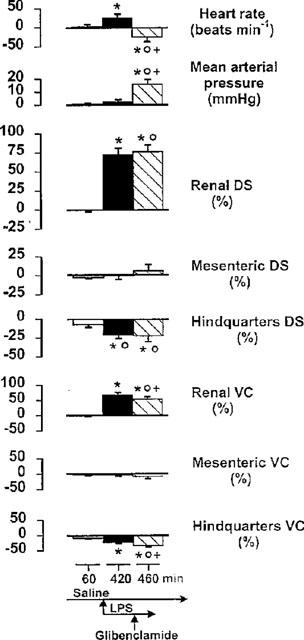

Infusion of saline was without significant effect, but, following 6 h coinfusion of LPS there was a slight tachycardia and increases in renal flow and vascular conductance and decreases in hindquarters flow and vascular conductance (Figure 2). Administration of glibenclamide caused a significant rise in MAP and converted the tachycardia to a bradycardia. Renal and hindquarters flow were not affected significantly, but the increase in renal vascular conductance was reduced slightly, and the decrease in hindquarters vascular conductance was slightly enhanced (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular changes (relative to the original baseline) in conscious Long Evans rats 60 min after the onset of saline infusion, 6 h after coinfusion of LPS, and 40 min after the subsequent administration of glibenclamide. Values are mean and vertical bars are s.e.mean, n=9; *P<0.05 versus original baseline; OP<0.05 versus 60 min value; +P<0.05 versus 420 min value (Kruskal-Wallis test); DS=Doppler shift; VC=vascular conductance.

Cardiovascular responses to glibenclamide after the onset of LPS infusion in the presence of losartan and SB 209670

In the three groups in this experiment, resting values were:- heart rate: 338±8, 349±8, and 338±8 beats min−1; MAP: 102±1, 104±1, and 101±2 mmHg; renal Doppler shift: 7.4±0.7, 8.0±0.8, and 8.0±0.8 kHz; mesenteric Doppler shift: 6.8±0.5, 8.3±0.8, and 8.5±0.9 kHz; hindquarters Doppler shift: 4.5±0.3, 4.5±0.4, and 4.9±0.4 kHz, renal vascular conductance: 73±7, 77±7, and 80±8 (kHz mmHg−1)103; mesenteric vascular conductance: 67±5, 80±8, and 84±8 (kHz mmHg−1)103; hindquarters vascular conductance: 44±3, 44±4, and 49±4 (kHz mmHg−1)103.

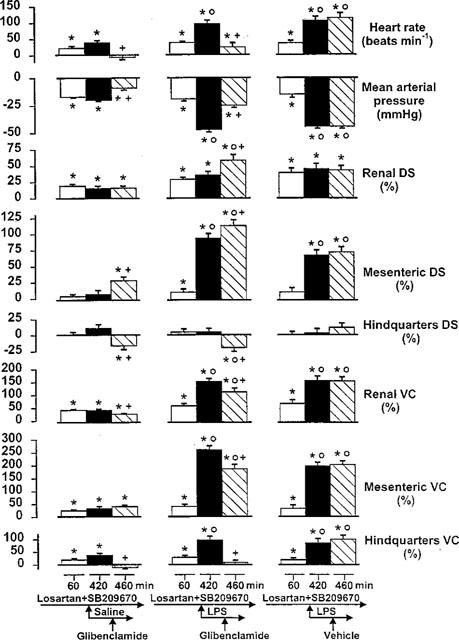

By 1 h after the onset of losartan and SB 209670 administration, there was a reduction in MAP accompanied by tachycardia. Only renal flow was increased, but conductances in renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vascular beds were raised (Figure 3). These changes were maintained during saline infusion, but during infusion of LPS the hypotension and tachycardia were markedly augmented, and there were substantial elevations in mesenteric flow and in renal mesenteric and hindquarters vascular conductances (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cardiovascular changes (relative to the original baseline) in conscious Long Evans rats 60 min after the onset of losartan and SB 209670 administration, 6 h after coinfusion of saline or LPS, and 40 min after the subsequent administration of glibenclamide or vehicle (n=6–9). Values are mean and vertical bars are s.e.mean; *P<0.05 versus original baseline; OP<0.05 versus 60 min value; +P<0.05 versus 420 min value (Kruskal-Wallis test). DS=Doppler shift; VC=vascular conductance.

In the presence of losartan, SB 209670 and saline, glibenclamide abolished the slight tachycardia and diminished the fall in MAP. Renal flow was not affected, but mesenteric flow rose and hindquarters flow fell (Figure 3). Hence, glibenclamide caused a slight diminution in renal vascular conductance, and abolished the rise in hindquarters conductance (Figure 3).

In the presence of losartan, SB 209670 and LPS, glibenclamide caused a significant reduction in the tachycardia and the hypotension, accompanied by increases in renal and mesenteric flows, but a decrease in hindquarters flow (Figure 3). There were reductions in renal and mesenteric vascular conductances and an abolition of the hindquarters vasodilatation (Figure 3). Glibenclamide vehicle was without effect (Figure 3).

Cardiovascular responses to glibenclamide after the onset of LPS infusion in the presence of losartan, SB 209670 and dexamethasone

In the three groups in this experiment, resting values were:- heart rate: 331±6, 322±6, and 328±4 beats min−1; MAP: 104±2, 104±2, and 103±1 mmHg; renal Doppler shift: 10.7±0.9, 6.6±0.6, and 6.7±0.5 kHz; mesenteric Doppler shift: 8.5±0.5, 7.1±0.6, and 6.7±0.4 kHz; hindquarters Doppler shift: 4.2±0.3, 4.4±0.7, and 3.7±0.3 kHz; renal vascular conductance: 102±9, 63±6, and 65±5 (kHz mmHg−1)103, mesenteric vascular conductance: 82±4, 68±6, and 65±4 (kHz mmHg−1)103; hindquarters vascular conductance: 41±3, 42±6, and 36±3 (kHz mmHg−1)103.

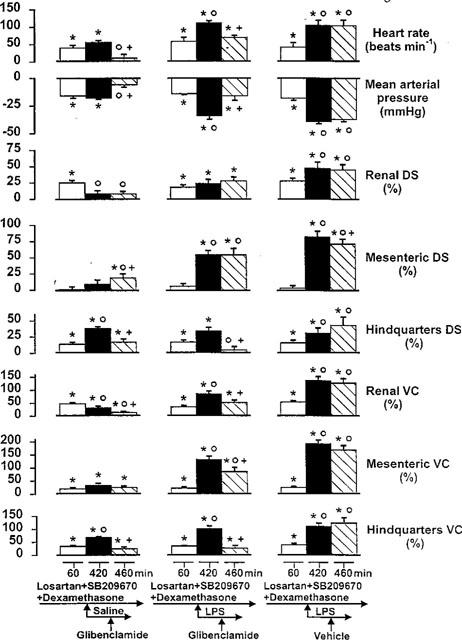

By 1 h after the onset of administration of losartan, SB 209670 and dexamethasone there were reductions in MAP accompanied by tachycardias (Figure 4). Renal and hindquarters flows were increased, and conductances were elevated in renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vascular beds (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cardiovascular changes (relative to the original baseline) in conscious Long Evans rats 60 min after the onset of losartan, SB 209670 and dexamethasone administration, 6 h after coinfusion of saline or LPS, and 40 min after the subsequent administration of glibenclamide or vehicle (n=6–9). Values are mean and vertical bars are s.e.mean; *P<0.05 versus original baseline; OP<0.05 versus 60 min value; +P<0.05 versus 420 min value (Kruskal-Wallis test). DS=Doppler shift; VC=vascular conductance.

During saline infusion the increases in renal flow and vascular conductance waned whereas the elevations in hindquarters flow and vascular conductance increased, although the tachycardia and hypotension remained unchanged (Figure 4). In contrast, in the presence of losartan, SB 209670 and dexamethasone, infusion of LPS caused clear augmentation of the tachycardia and hypotension, together with increases in renal, mesenteric and hindquarters flows and vascular conductances (Figure 4).

In the presence of losartan, SB 209670, dexamethasone and saline, glibenclamide caused an abolition of the tachycardia and the hypotension. There was an increase in mesenteric and a decrease in hindquarters flow, and reductions in renal and hindquarters vascular conductances (Figure 4).

In the presence of losartan, SB 209670, dexamethasone and LPS, glibenclamide suppressed the tachycardia and the hypotension, abolished the rise in hindquarters flow, and reduced the increases in renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vascular conductances (Figure 4). Glibenclamide vehicle was without effect (Figure 4).

Between-group comparisons of the effects of glibenclamide

Effects of glibenclamide in the absence of LPS

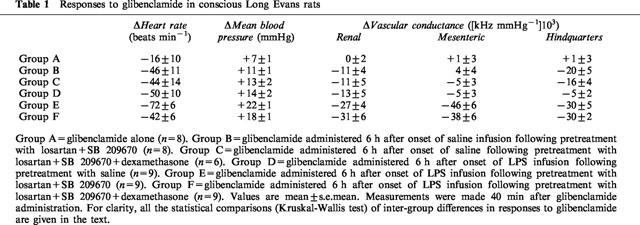

The pressor, bradycardic, and renal and hindquarters vasoconstrictor effects of glibenclamide in the presence of saline, losartan, and SB 209670, with or without dexamethasone, were significantly different from the minimal effects seen in animals receiving glibenclamide alone (Table 1, P<0.05, Group A versus B, and Group A versus C for changes in heart rate, MAP and renal and hindquarters vascular conductances; Kruskal-Wallis test). The effects of glibenclamide on heart rate, MAP and renal and hindquarters vascular conductances in the animals receiving saline after pre-treatment with losartan, SB209670 and dexamethasone were not significantly different from the effects observed in the group not receiving dexamethasone (Table 1, Group B versus C; Kruskal-Wallis test).

Table 1.

Responses to glibenclamide in conscious Long Evans rats

Effects of LPS on the cardiovascular responses to glibenclamide

The cardiovascular effects of glibenclamide were generally greater in the animals receiving LPS than in the corresponding groups receiving saline (Table 1, P<0.05 Group A versus D for changes in heart rate, MAP and renal vascular conductance; Group B versus E for changes in heart rate, MAP and renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vascular conductances; Group C versus F for changes in MAP, renal, mesenteric and hindquarters vascular condutances; Kruskal-Wallis test).

Effects of dexamethasone on the cardiovascular responses to glibenclamide in the presence of LPS

The cardiovascular effects of glibenclamide in the animals receiving LPS after pretreatment with losartan, SB 209670 and dexamethasone were not significantly different from the effects observed in the group not receiving dexamethasone, with the exception of the bradycardia which was larger in the latter (Table 1, Group E versus F; P<0.05 for changes in heart rate; Kruskal-Wallis test).

Blood glucose levels

For the three groups in the first experiment (Figure 1) blood glucose values were as follows:- vehicle/LPS: before, 4.95±0.15 mmol l−1; after, 3.56±0.16 mmol l−1; glibenclamide/LPS: before, 4.85≈thinsp;+ 0.29 mmol l−1; after, 1.42± 0.13 mmol l−1; glibenclamide/saline: before, 4.63±0.30; after, 1.75±0.15 mmol l−1. All changes were significant (P<0.05; Wilcoxon test), however, glibenclamide caused a similar fall in blood glucose in the presence of saline or LPS, thus there was no relation between its hypoglycaemic and haemodynamic effects, and this was also the case for the other groups in which blood glucose were measured (data not shown).

Discussion

The results of the present studies have shown cardiovascular effects of glibenclamide which may be interpreted as evidence for a regionally-selective activation of KATP-channel-mediated vasodilator mechanisms in endotoxaemia.

In the first series of experiments, the most striking effect of pretreatment with glibenclamide on the haemodynamic effects of LPS was that it promoted a progressive rise in blood pressure associated with developing vasoconstriction, particularly in the hindquarters vascular bed. However, on the basis of those findings alone, we could not infer the involvement of KATP-channels, since there is some evidence that glibenclamide may inhibit iNOS expression (Wu et al., 1995), and we know that the cardiovascular consequences of inhibiting iNOS expression (with aminoguanidine) are particularly marked around 5–6 h after the onset of LPS infusion (Gardiner et al., 1996b) i.e., at a time when iNOS expression is maximal (Gardiner et al., 1995), which coincides with the time of greatest effect of glibenclamide. Indeed, there are some similarities between the regional vascular effects of pretreatment with aminoguanidine (Gardiner et al., 1996b) and glibenclamide (this study) on the cardiovascular responses to LPS infusion, although there are certain differences, particularly with regard to the extent of mesenteric vasoconstriction.

However, the results of our subsequent experiments indicated, more directly, an involvement of KATP-channel-mediated vasodilatation since, in those, it was shown that glibenclamide had pressor and hindquarters vasoconstrictor effects when administered 6 h after the onset of the LPS infusion, i.e. at a stage when iNOS expression would have been established (Gardiner et al., 1995). In the animals receiving LPS infusion in the presence of saline, the effects of glibenclamide were relatively modest. But, under conditions in which the vasoconstrictor effects of angiotensin and endothelin were antagonised, the influence of glibenclamide was more pronounced, and the same applied, albeit to a lesser degree, in the absence of LPS. This could mean either that the extent of vasodilatation, rather than a feature of the endotoxaemic state, is partly responsible for the activation of KATP-channels, or that the vasoconstrictor peptides, angiotensin and endothelin, were specifically inhibiting KATP-channel activation (see review, Quayle & Standen, 1994). Either way, it remains to explain why the effect was most marked in the hindquarters, since it was only in that vascular bed the vasoconstrictor effect of glibenclamide was associated with a reduction in flow. Angiotensin and endothelin are both potent constrictors of the renal and mesenteric vascular beds in conscious rats (Gardiner et al., 1988; 1990), hence removal of any inhibitory effect of those peptides would not be anticipated to be manifest only in the hindquarters, unless KATP-channels predominate in that region. However, this is unlikely, since the vasodilator effects of the KATP-channel agonist, levcromakalim, are particularly marked in the mesenteric vascular bed (Gardiner et al., 1991). In pregnant guinea pigs it has been shown that glibenclamide causes renal vasoconstriction associated with a reduction in renal blood flow (Keyes et al., 1998), whereas in cirrhotic rats the pressor effects of glibenclamide are not associated with reductions in renal blood flow (Moreau et al., 1994). Thus, it is possible that the activation of KATP-channels is secondary to underlying metabolic changes, which may be regionally differentiated and variable, depending on the (patho) physiological state.

Recently, it has been shown that insulin inhibits NO production by iNOS (but does not inhibit iNOS expression), specifically in skeletal muscle cells (Bédard et al., 1998). Thus, it was feasible that the effects we observed in the LPS-treated rats were due to glibenclamide-stimulated insulin release causing inhibition of NO production. However, in the study of Bédard et al. (1998) it was shown that the inhibitory effects of insulin were similar to those of dexamethasone (although combined insulin and dexamethasone had a somewhat greater inhibitory effect than either substance alone). In our experiments, in which dexamethasone was administered, iNOS expression would have been inhibited, yet the pressor and vasoconstrictor effects of glibenclamide were the same as in the absence of dexamethasone. For this reason we believe that the cardiovascular effects of glibenclamide we observed were most likely due to specific inhibition of KATP-channel-mediated vasodilatation, although, since we did not measure cardiac output, we cannot conclude that the pressor effects of glibenclamide were entirely dependent on its vascular actions. As mentioned in the Introduction, Vanelli et al. (1995) have excluded an increase in cardiac output contributing to the pressor action of glibenclamide in their model of septic shock, but this may not be the case in the conscious rats in our protocols. In this context, however, it is notable that the pressor effects of glibenclamide were accompanied by bradycardia, possibly of reflex origin. It is unlikely, therefore, that there would have been an increased cardiac output in this situation, but direct measurement of this variable (Gardiner et al., 1995) is required to resolve this question.

In conclusion, the present work has provided some evidence for the involvement of KATP-channels in the vasodilator responses to LPS infusion in conscious rats. However, there is no straightforward explanation for the apparent regional selectivity of the effects of glibenclamide. It is unlikely that this was due to flow-mediated activation of KATP-channels. because the increases in flow in renal and mesenteric vascular beds were greater than those in the hindquarters. A possible explanation for a selective activation of KATP-channels in the hindquarters vascular bed is that this was due to LPS-induced metabolic disturbances in hindquarters skeletal muscle, this effect predominating simply because of the relatively large mass of skeletal muscle, and its contribution to lactic acidaemia consequent upon anaerobic glycolysis (Landry & Oliver, 1992). In our model of endotoxaemia we have found a fall in plasma bicarbonate, indicative of the occurrence of metabolic acidaemia, although this measurement was made 23 h after the onset of LPS infusion (Gardiner et al., 1999b), rather than at an earlier time point corresponding to the haemodynamic measurements made in the current study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MRC (ROPA scheme).

Abbreviations

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KATP-channels

ATP-sensitive K+ channels

- MAP

mean arterial blood pressure

- VC

vascular conductance

References

- BATIN P., GARDINER S.M., COMPTON A.M., BENNETT T. Differential regional haemodynamic effects of the non-peptide angiotensin II antagonist, DuP 753, in water-replete and water-deprived Brattleboro rats. Life Sci. 1991;48:733–739. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90087-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÉDARD S., MARCOTTE B., MARETTE A. Insulin inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase in skeletal muscle cells. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1523–1527. doi: 10.1007/s001250051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHALLINOR-ROGERS J.L., MCPHERSON G.A. Potassium channel openers and other regulators of KATP channels. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1994;21:583–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1994.tb02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., BENNETT T., COMPTON A.M. Regional haemodynamic effects of neuropeptide Y, vasopressin and angiotensin II in conscious, unrestrained, Long Evans and Brattleboro rats. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1988;24:15–27. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., COMPTON A.M., BENNETT T. Regional haemodynamic effects of endothelin-1 and endothelin-3 in conscious Long Evans and Brattleboro rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;99:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., BENNETT T. Effects of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester on vasodilator responses to adrenaline or BRL 38227 in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104:731–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Cardiac and regional haemodynamics, inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity, and the effects of NOS inhibitors in conscious, endotoxaemic rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2005–2016. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Effects of dexamethasone and SB 209670 on the regional haemodynamic responses to lipopolysaccharide in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996a;118:141–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Influence of aminoguanidine and the endothelin antagonist, SB 209670, on the regional haemodynamic effects of endotoxaemia in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996b;118:1822–1828. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Temporal differences between the involvement of angiotensin II and endothelin in the cardiovascular responses to endotoxaemia in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996c;119:1619–1627. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Effects of glibenclamide on regional haemodynamic responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:392P. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Evidence for involvement of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), but not adrenomedullin (ADM), in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced vasodilatation in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998a;124:120P. [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Effects of glibenclamide on vasodilatation during endotoxaemia in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999a;126:187P. [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., BENNETT T. Influence of FR 167653, an inhibitor of TNF-α and IL-1, on the cardiovascular responses to chronic infusion of lipopolysaccharide in conscious rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1999b;34:64–69. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199907000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., FALLGREN B., BENNETT T. Effects of glibenclamide on the regional haemodynamic actions of α-trinositol and its influence on responses to vasodilators in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996d;117:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., KEMP P.A., MARCH J.E., WOOLLEY J., BENNETT T. The influence of antibodies to TNF-α and IL-1β on haemodynamic responses to the cytokines, and to lipopolysaccharide, in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998b;125:1543–1550. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARDINER S.M., MARCH J.E., KEMP P.A., BENNETT T. Influence of CGRP (8-37), but not adrenomedullin (22-52), on the haemodynamic responses to lipopolysaccharide in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999c;127:1611–1618. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUC M.O., FURMAN B.L., PARRATT J.R. Endotoxin-induced impairment of vasopressor and vasodepressor responses in the pithed rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;101:913–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14180.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JULOU-SCHAEFFER G., GRAY G.A., FLEMING I., SCHOTT C., PARRATT J.R., STOCLET J.-C. Loss of vascular responsiveness induced by endotoxin involves L-arginine pathway. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:H1038–H1043. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEYES L., RODMAN D.M., CURRAN-EVERETT D., MORRIS K., MOORE L.G. Effect of K+ATP channel inhibition on total and regional vascular resistance in guinea pig pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:H680–H688. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KILBOURN R.G., SZABO C., TRABER D.L. Beneficial versus detrimental effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors in circulatory shock: lessons learned from experimental and clinical studies. Shock. 1997;7:235–246. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANDRY D.W., OLIVER J.A. The ATP-sensitive K+ channel mediates hypotension in endotoxemia and hypoxic lactic acidosis in dog. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:2071–2074. doi: 10.1172/JCI115820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOREAU R., KOMEICHI H., KIRSTETTER P., OHSUGA M., CAILMAIL S., LEBREC D. Altered control of vascular tone by adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels in rats with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1016–1023. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90762-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUAYLE J.M., STANDEN N.B. KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle. Cardiovasc. Res. 1994;28:797–804. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REES D.D., CELLEK S., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. Dexamethasone prevents the induction by endotoxin of a nitric oxide synthase and the associated effects on vascular tone: an insight into endotoxin shock. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;173:541–547. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHALLER M.D., WAEBER B., NUSSBERGER J., BRUNNER H.R. Angiotensin II, vasopressin, and sympathetic activity in conscious rats with endotoxaemia. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;249:H1086–H1092. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.6.H1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZABO C., MITCHELL J.A., THIEMERMANN C., VANE J.R. Nitric oxide-mediated hyporeactivity to noradrenaline precedes the induction of nitric oxide synthase in endotoxin shock. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:786–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THIEMERMANN C., VANE J. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis reduces the hypotension induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in the rat in vivo. Eur. Pharmacol. 1990;182:591–595. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANELLI G., HUSSAIN S.N.A., AGUGGINI G. Glibenclamide, a blocker of ATP-sensitive potassium channels, reverses endotoxin-induced hypotension in pig. Exp. Physiol. 1995;80:167–170. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLER J., GARDINER S.M., BENNETT T. Changes in regional haemodynamics and in responses to acetylcholine and methoxamine during infusion of lipopolysaccharide in conscious rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:1057–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU C.-C., THIEMERMANN C., VANE J.R. Glibenclamide-induced inhibition of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in cultured macrophages and in the anaesthetized rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1273–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]