Abstract

Guanosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic GMP)-dependent kinase I (cGKI) is a major receptor for cyclic GMP in a variety of cells. Mice lacking cGKI exhibit multiple phenotypes, including severe defects in smooth muscle function. We have investigated the NO/cGMP- and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)/adenosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic AMP)-signalling pathways in the gastric fundus of wild type and cGKI-deficient mice.

Using immunohistochemistry, similar staining patterns for NO-synthase, cyclic GMP- and VIP-immunoreactivities were found in wild type and cGKI-deficient mice.

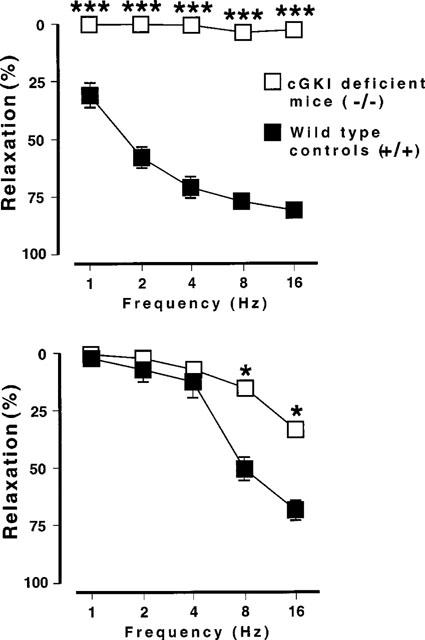

In isolated, endothelin-1 (3 nM–3 μM)-contracted, muscle strips from wild type mice, electrical field stimulation (1–16 Hz) caused a biphasic relaxation, one initial rapid, followed by a more slowly developing phase. In preparations from cGKI-deficient mice only the slowly developing relaxation was observed.

The responses to the NO donor, SIN-1 (10 nM–100 μM), and to 8-Br-cyclic GMP (10 nM–100 μM) were markedly impaired in strips from cGKI-deficient mice, whereas the responses to VIP (0.1 nM–1 μM) and forskolin (0.1 nM–1 μM) were similar to those in wild type mice.

These results suggest that cGKI plays a central role in the NO/cGMP signalling cascade producing relaxation of mouse gastric fundus smooth muscle. Relaxant agents acting via the cyclic AMP-pathway can exert their effects independently of cGKI.

Keywords: cyclic GMP, enteric nervous system, nitric oxide, non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) or a NO-related compound has been demonstrated to be an important physiological mediator of non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC) relaxation of gastrointestinal smooth muscle (Sanders & Ward, 1992; Stark & Szurszewski, 1992). In the gut, NO seems to produce its effects both via direct activation of potassium ion channels and by stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC; Sanders & Ward, 1992; Shuttleworth et al., 1993; Young et al., 1993; Koh et al., 1995). Activation of sGC leads to generation of guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic GMP) from guanosine triphosphate. Several targets for cyclic GMP have been identified, including cyclic GMP-gated ion channels, cyclic GMP stimulated/inhibited phosphodiesterases, and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases (Lohmann et al., 1997). Two forms of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases, type I (cGKI, Sandberg et al., 1989; Wernet et al., 1989), and type II (cGKII, Uhler, 1993), have been identified. They have a wide tissue distribution. cGKII has been found in e.g. developing bone and secretory cells, whereas cGKI is highly expressed in smooth muscle, platelets and cerebellum (Waldmann et al., 1986; Keilbach et al., 1992; Pfeifer et al., 1996). Recently, it was demonstrated that mice lacking cGKI have a defective smooth muscle function (Pfeifer et al., 1998) leading to hypertension and general gastrointestinal dysmotility.

Relatively little is known about the NO/cyclic GMP system in the gastrointestinal tract of mice. However, similar to what has been found in other species, the NO-synthesizing enzyme, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), has been localized to nerve structures in the muscle wall, and NO-mediated neurotransmission has been demonstrated in several gastrointestinal regions including the gastric fundus (Lefebvre, 1993; Burns et al., 1996; Ögulener et al., 1995; Sang & Young, 1996; Ny & Andersson, 1998). Besides NO, other NANC mediators have been proposed to be involved in the mediation of relaxation of gastrointestinal smooth muscle. One of these candidates is vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), which is considered to act via activation of the adenylyl cyclase/adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic AMP) signal transduction pathway. Some studies have indicated that NO directly influences the release of VIP and vice versa (Makhlouf & Grider, 1993; Jin et al., 1996), whereas others have suggested that NO and VIP act in parallel (Barbier & Lefebvre, 1993; Keef et al., 1994; Bayguinov et al., 1999).

Mice lacking cGKI offer an opportunity to study the effects of VIP and other agents acting through the cyclic AMP signalling cascade in the absence of the NO/cyclic GMP/cGKI pathway. Therefore, we have investigated the NO/cyclic GMP-and the VIP/cyclic AMP-pathways in wild type and cGKI-deficient mice, testing the hypothesis that there may be a cross-talk between the cyclic GMP and cyclic AMP signalling cascades in gastrointestinal smooth muscle, as has been suggested by other investigators in other systems (Jiang et al., 1992; Lincoln et al., 1995). As a test preparation we chose the fundus of the stomach.

Methods

Tissue preparation

Adult (20–25 g) cGKI-deficient mice of both sexes, produced as described previously (Pfeifer et al., 1998), and wild type controls, were bred and maintained at the animal house of the Department of Experimental Pathology, University of Lund. The animals were killed by CO2 asphyxia and decapitated. Age- and sex-matched wild type mice served as controls and were treated similarly. This procedure was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Lund University. The abdomen was opened and the upper digestive tract removed. The gastric fundus was identified and tissue specimens from this region were dissected and examined morphologically and functionally.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue specimens comprising the whole gastric fundus wall were fixed for 4 h in a 4°C solution of 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), and rinsed in 15% sucrose in PBS. The tissue pieces were then processed and investigated as described previously (Ny et al., 1995).

The sections were incubated overnight with primary antisera raised against mouse cGKI (1 : 2000, in rabbit; see Pfeifer et al., 1998), rat neuronal NOS (1 : 2000; in sheep; supplied by Dr P. Emson, Cambridge, U.K.), porcine VIP (1 : 500; in guinea-pig; Eurodiagnostica, Malmö, Sweden). cyclic GMP-immunoreactivities were investigated in the tissue by using an antiserum against cyclic GMP (1 : 1000, in sheep; supplied by Dr J. De Vente, Leiden, The Netherlands) in the tissue following a 30 min preincubation period with 1 mM sodium nitroprusside in the presence of zaprinast (1 mM) and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; 1 mM) as described previously (Waldeck et al., 1998).

After the incubation period with the primary antisera, the sections were rinsed in PBS, and then incubated for 90 min with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated swine anti-rabbit, goat anti-guinea-pig or donkey anti-sheep immunoglobulins (all 1 : 80 in PBS; Sigma, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Subsequently, the sections were mounted in glycerol/PBS with p-phenylenediamine to prevent fluorescence fading.

Functional studies

Circular smooth muscle preparations (1 mm wide and 10–12 mm long) were dissected and mounted in tissue baths, and mechanical activity was recorded as described previously (Ny et al., 1995). To be able to study relaxant responses the strips were precontracted by endothelin-1 (3 nM–3 μM), which induces a tension level of approximately 50–70% of a 124 mM K+-induced contraction in mice gastric fundus smooth muscle preparations (L. Ny, 1999, unpublished observations). At the end of the experiments, the strips were exposed to a Ca2+-free Krebs solution (see below) to define the basal contraction level from which all calculations were related.

Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was performed as described previously (Ny et al., 1995). The stimulation frequency was varied between 1–16 Hz. Five-second trains of square wave pulses (0.5 ms duration, supramaximal voltage) were delivered every 2 min. All experiments were carried out in the presence of indomethacin (1 μM), phentolamine (1 μM), propranolol (1 μM), and scopolamine (1 μM). Two relaxation phases were observed (see below). The maximum relaxation for each phase was registered and compared.

Solutions

The Krebs solutions used had the following composition (in mM): Na+-Krebs solution: NaCl 119, KCl 4.6, NaHCO3 15, CaCl2 1.5, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2 and glucose 5.5. Ca2+-free Krebs solution: NaCl 119, KCl 4.6, NaHCO3 15, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2, EGTA 0.1 and glucose 5.5.

Drugs

The chemicals were obtained from the following sources: 8-Br-cyclic GMP, IBMX, NG-nitro-L-arginine (L-NOARG), (±)-propranolol hydrochloride, scopolamine hydrochloride, sodium nitroprusside, VIP, and zaprinast from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), 3-morpholino-sydnonimin (SIN-1) from Casella AG (Frankfurt, Germany), phentolamine methane sulphonate from Ciba-Geigy/Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), endothelin-1 from Peninsula (Belmont, CA, U.S.A.), indomethacin (Confortid) from Dumex (Copenhagen, Denmark), and), 1H-[1,2,4]-oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), from Tocris Cookson Ltd (Bristol, U.K.). All drugs were dissolved in saline.

Statistical analysis

Statistical results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. When statistical differences between two means were determined, an unpaired Student's t-test was performed. P<0.05 was regarded as significant. N refers to the number of animals and n to the number of strips tested. When statistical analyses between means were performed, all values refer to different animals. 8-Br-cyclic GMP, SIN-1, forskolin and VIP were added cumulatively and concentration-response curves were constructed.

Results

Morphology

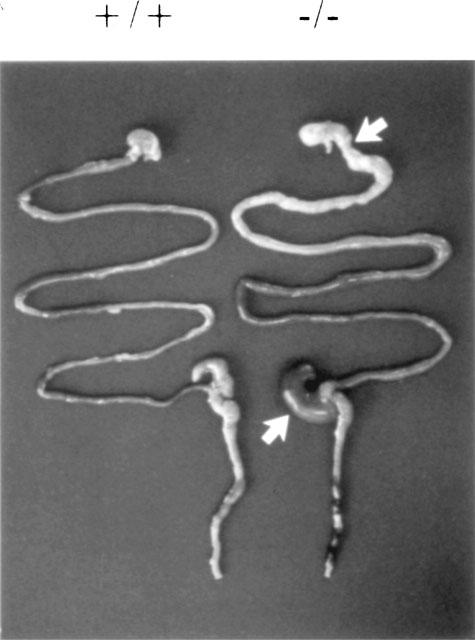

The morphological appearance of the gastrointestinal tract of cGKI-deficient mice was markedly different from that in wild type controls (Figure 1). The stomach was dilated and the pylorus contracted in the cGKI-deficient mice. There was a poststenotic dilation of the duodenum. Macroscopically no great differences in the appearances of the rest of the small intestine were observed. The ileocaecal region of cGKI-deficient mice was contracted and the caecum markedly dilated. No dilation was found in the rest of the large bowel.

Figure 1.

The gastrointestinal tract at autopsy of 5 week-old wild type (left) and litter-matched cGKI-deficient mouse (right). Arrows indicate the pylorus and the caecum of the cGKI-deficient mouse.

Immunohistochemistry

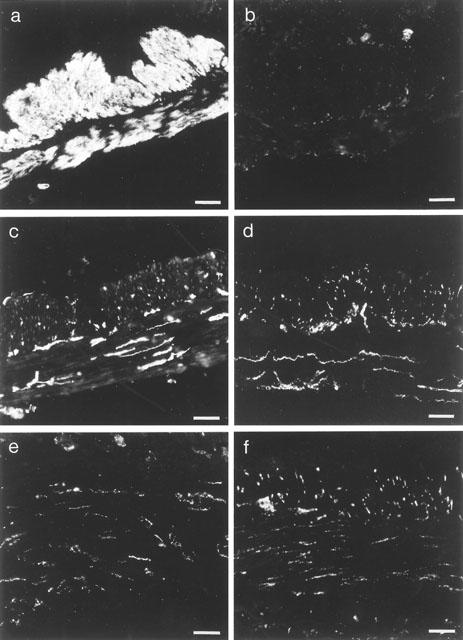

In cGKI-deficient mice, no immunoreactivity against cGKI could be demonstrated, whereas in the wild type mice an intense cGKI-immunoreactivity was observed that was confined to the smooth muscle cells in the submucosa, the inner circular, and the outer longitudinal muscle layers (Figure 2a,b). In both cGKI-deficient and wild type mice, NOS-immunoreactivity was observed in numerous nerve cell bodies in the enteric plexuses and in nerve fibres (Figure 2c,d). The nerves were mainly localized to the inner circular muscle layer. No apparent differences in quantity and distribution pattern were observed between cGKI-deficient and wild type mice. VIP-immunoreactivity had a similar staining pattern as NOS-immunoreactivity, although the number of large nerve fibres seemed to be less in comparison to the number of NOS-IR fibres (Figure 2e,f).

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence images of the gastrointestinal wall from the gastric fundus of wild type (a,c,e) and cGKI-deficient (b,d,f) mice. (a) and (b) demonstrate cGKI-immunoreactivity, (c) and (d) demonstrate NOS-immunoreactivity, and (e) and (f) demonstrate VIP-immunoreactivity. Bar 100 μm.

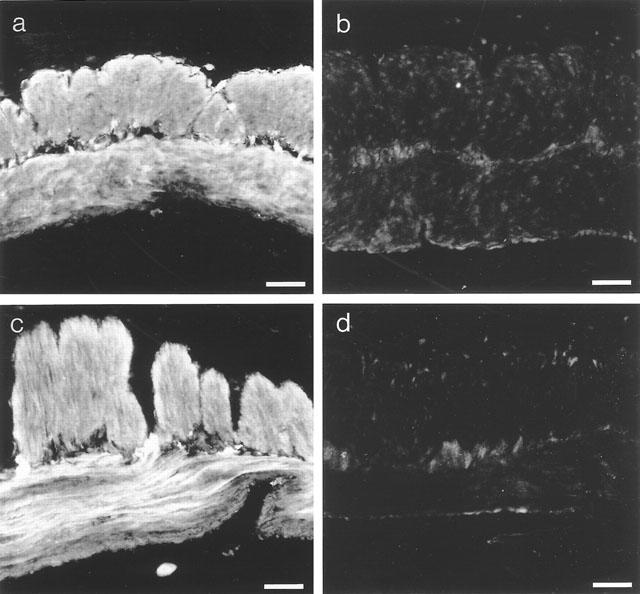

Cyclic GMP-immunoreactivity was observed in smooth muscle cells of both the circular and longitudinal muscle layers. The staining pattern for cyclic GMP-immunoreactivity was similar in cGKI-deficient and wild type mice (Figure 3a–d). cyclic GMP-immunoreactivity was only observed in tissue preincubated with sodium nitroprusside in the presence of IBMX and zaprinast. Omission of sodium nitroprusside preincubation resulted in no staining.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence images demonstrating cyclic GMP-immunoreactivity in the gastrointestinal wall from the gastric fundus of wild type (a,b) and cGKI-deficient (c,d) mice. (a) and (c) demonstrate the immunoreactivity after preincubation of sodium nitroprusside, whereas (b) and (d) without. Bar 100 μm.

Functional studies

Endothelin-1 (3 nM–3 μM) induced a stable tension level amounting to 4.5±0.5 mN (n=41, N=12) in cGKI-deficient mice, and 5.1±0.4 mN in wild type mice (n=40, N=12).

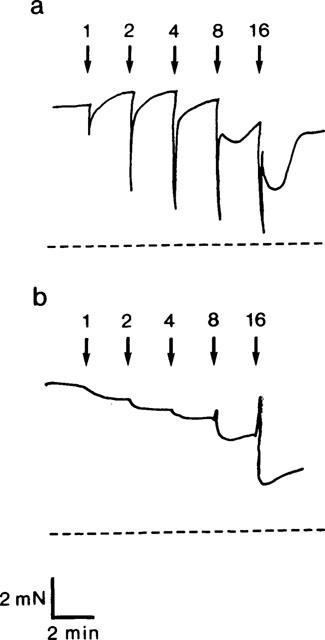

In wild type mice, EFS (1–16 Hz) induced frequency-dependent relaxations. These consisted of a rapid and transient first phase, reaching its maximum within 2–8 s. Tension was then transiently restored to starting values, and then a second relaxation phase was observed with a slower onset time and a longer duration (Figures 4 and 5). The second phase, which reached its maximum 20–40 s after initiation of EFS, could be observed only at low-frequency stimulation (1–4 Hz) in strips from two animals, whereas high-frequency stimulation (8–16 Hz) resulted in a biphasic relaxation in strips from all animals. In cGKI-deficient mice, practically no transient relaxations could be observed (Figures 4 and 5). Instead, only a long-lasting relaxation, similar to the second phase relaxation in the wild type mice, could be demonstrated (Figures 4 and 5). This relaxation was especially prominent using high-frequency stimulation (8–16 Hz). In cGKI-deficient mice, the amplitude of the second phase, expressed in percent of the endothelin-1 induced tension, was slightly less than in wild type mice (P<0.05; Figure 6). At 8–16 Hz frequency stimulation, the relaxations in cGKI-deficient mice were preceded by a frequency-dependent ‘on' contraction (Figure 4b), which was not sensitive to L-NOARG or ODQ. No EFS-induced contractions were observed in wild type mice.

Figure 4.

Original tracings showing electrical field stimulation (supramaximal voltage, 0.5 ms pulses, varying frequency 1–16 Hz)-induced relaxations of the gastric fundus. (a) wild type mice. (b) cGKI-deficient mice.

Figure 5.

(Upper part) The first relaxant phase of the response to electrical field stimulation (supramaximal voltage, 0.5 ms pulses, varying frequency 1–16 Hz) nerves in smooth muscle strips from the mouse gastric fundus. Wild type mice: n=6; cGKI-deficient mice: n=6. (Lower part) The second relaxant phase of the response to electrical field stimulation (supramaximal voltage, 0.5 ms pulses, varying frequency 1–16 Hz) nerves in smooth muscle strips from the mouse gastric fundus. Wild type mice: n=6; cGKI-deficient mice: n=6. *P<0.05.

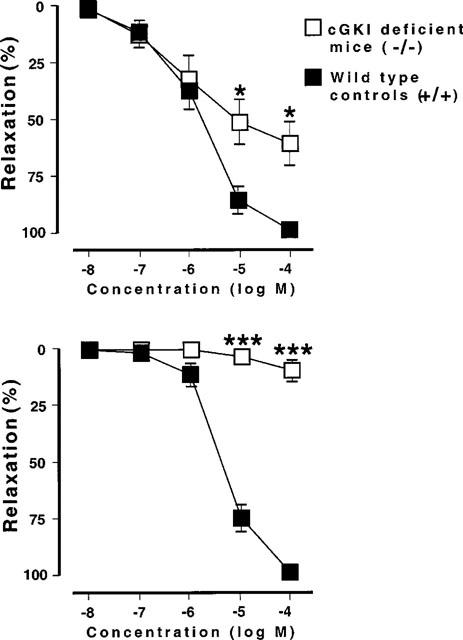

Figure 6.

(Upper part) SIN-1-induced relaxation of smooth muscle strips from in the mouse gastric fundus. Wild type mice: n=6; cGKI-deficient mice: n=6: *P<0.05. (Lower part) 8-Br-cyclic GMP-induced relaxation of smooth muscle strips from the gastric fundus. Wild type mice: n=6; cGKI-deficient mice: n=6. ***P<0.001.

L-NOARG (100 μM) treatment during EFS (2 or 8 Hz), or after 30 min preincubation before EFS (1–16 Hz), resulted in abolition of the first relaxant phase in wild type mice. In some preparations, a contraction was seen instead. A maximum effect was observed after approximately 10–15 min of L-NOARG treatment. In both cGKI-deficient and wild type mice, L-NOARG reduced also the EFS (8 Hz)-induced second/long-lasting relaxant phase (P<0.05; data not shown).

ODQ (1 μM) applied during EFS (2 or 8 Hz), or after 30 min preincubation before EFS (1–16 Hz), produced a major reduction, and occasionally a disappearance, of the first relaxant phase in wild type mice. A maximum reduction from 59±7 to 5±2 % at 2 Hz, and from 87±8 to 41±8% at 8 Hz (n=4) was seen after 15–20 min treatment. Corresponding values in cGKI−/−mice were 1±1 and 1±1 % (2 Hz), and 10±5 and 8±4 %. In both cGKI-deficient- and wild type mice, ODQ reduced also the EFS (8 Hz) induced second/long-lasting relaxant phase (P<0.05; data not shown).

SIN-1 (10 nM–100 μM) induced a concentration-dependent relaxation in both cGKI-deficient and wild type mice (Figure 6). At high concentrations (10–100 μM) the relaxant response to SIN-1 was markedly reduced in cGKI-deficient mice in comparison to wild type mice. The maximum relaxations were in wild type mice 99±1% (n=6) and in cGKI-deficient mice 61±9% (n=6; P<0.05). 8-Br-cyclic GMP (10 nM–100 μM) induced a concentration-dependent relaxation in the wild type mice reaching a maximum relaxation amounting to 99±1% (n=6; Figure 6). In cGKI-deficient mice, the relaxation was markedly reduced, reaching a maximum amounting to 10±5 % (n=6).

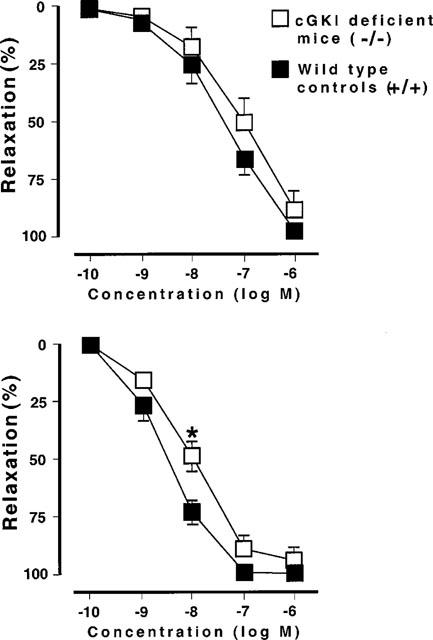

VIP (0.1 nM–1 μM) induced a concentration-dependent relaxation in both cGKI-deficient and wild type mice (Figure 7). The relaxant response in cGKI-deficient mice was slightly less at 10 nM (P<0.05), but at the other concentrations, no significant differences were found. The maximal relaxations were 100±0% (n=6) and 94±6% (n=6) in wild type and cGKI-deficient mice, respectively. Forskolin (0.1 nM–1 μM) induced a concencentration-dependent relaxation with no significant differences between wild type and cGKI-deficient mice (Figure 7). The maximal relaxations were 96±2% (n=6) and 89±5% (n=6) in wild type and cGKI-deficient mice, respectively.

Figure 7.

(Upper part) Forskolin-induced relaxation of smooth muscle strips from the gastric fundus. Wild type mice: n=6; cGKI-deficient mice: n=6. (Lower part) VIP-induced relaxation of smooth muscle strips from the gastric fundus. Wild type mice: n=6; cGKI-deficient mice: n=6. *P<0.05.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that cGKI has an obligatory role in the NO-mediated relaxation of the mouse gastric fundus. Preparations from wild type mice exhibited a pronounced relaxation consisting of two phases, where the first phase was markedly inhibited by the sGC inhibitor, ODQ, or the NO-synthesis inhibitor, L-NOARG. This strongly suggests that this relaxation was mediated by the NO/cyclic GMP pathway. Indeed, strips from cGKI-deficient mice did not exhibit the first response, but only the slowly developing second relaxation. Moreover, preparations from cGKI-deficient mice responded weakly to 8-Br-cyclic GMP, and the SIN-1 induced relaxation was markedly reduced, clearly indicating that these exogenously administered drugs also need cGKI to exert their effects. The slight SIN-1 mediated relaxation that was observed at high concentrations in both types of animal, suggests that this NO-donor may activate other pathways than the one used by endogenous NO, released from nerves. It is well known from other investigations that NO can activate ion channels in gastrointestinal smooth muscle leading to hyperpolarization and relaxation (Bolotina et al., 1994; Koh et al., 1995).

A loss of cGKI could be expected to produce changes both upstream and downstream in the signal transduction cascade. However, in the cGKI-deficient mice we found no evidence for any upstream change. The NOS-innervation was the same and so was the distribution of cyclic GMP-staining smooth muscle cells.

It may be speculated that alternative pathways can be activated and/or upregulated which try to compensate for the loss of function in the cGKI-deficient mice. In the present sets of experiments we found no differences in immunohistochemical staining between controls and cGKI-deficient animals. There were no major changes in the response to VIP, another putative NANC mediator in the mouse fundus, or to the adenylyl cyclase stimulator, forskolin. In other smooth muscle systems, a cross-talk has been demonstrated between the cyclic GMP- and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinases (Jiang et al., 1992). It seems clear however, that the signalling pathway used by VIP and forskolin may function independently of cGKI, since 8-Br-cyclic GMP and drugs believed to be acting through the cyclic GMP/cGKI pathway had little or no effect in cGKI-deficient mice. Thus, significant actions of cyclic GMP on cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinases seem to be excluded.

A matter of much debate in the discussion of NO-mediated effects in the gastrointestinal tract has been whether or not VIP is crucial for NO-mediated effects and vice versa (Makhlouf & Grider, 1993; Keef et al., 1994; Bayguinov et al., 1999). In the present experiments, where the NO-generation system is intact in both types of animals investigated, we have not been able to demonstrate any major qualitative differences between wild type and cGKI-deficient mice in the response to VIP or forskolin. However, the second relaxation phase of the electrically induced relaxation, observed mainly at 8 and 16 Hz, and possibly mediated by VIP, was reduced in cGKI-deficient compared to wild type mice. The cGKI-deficient mice also exhibited an on-contraction at 8 and 16 Hz, which the wild type did not. If this is related to an interplay between NO and a second transmitter, possibly VIP, can only be speculated upon.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that cGKI has an obligatory role in NO-mediated relaxation of the mouse gastric fundus. Interactions between NO and another relaxing agent cannot be excluded. However, agents acting via cyclic AMP may be able to act more or less independent of cGKI when producing relaxation of mouse gastric smooth muscle.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Piers Emson and J De Vente for generous supply of NOS and cyclic GMP antisera, respectively. Alexander Pfeifer is on leave of absence from the Institut für Pharmakologie und Toxikologie, Technische Universität, München, Germany. This study were supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council (grants no 6837 and 11205), the Crafoord foundation, and the Osterlund foundation.

Abbreviations

- cGKI

cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- IR

immunoreactive

- L-NOARG

NG-nitro-L-arginine

- NANC

non-adrenergic non-cholinergic

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4]-oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one

- sGC

soluble guanylate cyclase

- SIN-1

3-morpholino-sydnonimin

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

References

- BARBIER A.J., LEFEBVRE R.A. Involvement of the L-arginine:nitric oxide pathway in nonadrenergic noncholinergic relaxation of the cat gastric fundus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;266:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAYGUINOV O., KEEF K.D., HAGEN B., SANDERS K.M. Parallel pathways mediate inhibitory effects of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and nitric oxide in canine fundus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1543–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOLOTINA V.M., NAJIBI S., PALACINO J.J., PAGANO P., COHEN R.A. Nitric oxide directly activates calcium-dependent potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Nature. 1994;368:850–853. doi: 10.1038/368850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNS A.J., LOMAX A.E., TORIHASHI S., SANDERS K.M., WARD S.M. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate inhibitory neurotransmission in the stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:12008–12013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIANG H., COLBRAN J.L., FRANCIS S.H., CORBIN J.D. Direct evidence for cross-activation activation of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase by cyclic AMP in pig coronary arteries. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN J.G., MURTHY K.S., GRIDER J.R., MAKHLOUF G.M. Stoichiometry of neurally induced VIP-release, NO formation, and relaxation in rabbit and rat gastric muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:G357–G369. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.2.G357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEEF K.D., SHUTTLEWORTH C.W.R., XUE C., BAYGUINOV O., PUBLICOVER N.G., SANDERS K.M. No relationship between nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in enteric inhibitory neurotransmission. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1303–1314. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEILBACH A., RUTH P., HOFMANN F. Detection of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase isozymes by specific antibodies. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;208:467–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOH S.D., CAMPBELL J.D., CARL A., SANDERS K.M. Nitric oxide activate potassium channels in canine colonic smooth muscle. J. Physiol. 1995;489:735–743. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFEBVRE R.A. Non-adrenergic non-cholinergic neurotransmission in the proximal stomach. Gen. Pharmacol. 1993;24:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(93)90301-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINCOLN T.M., KOMALAVILAS P., MACMILLAN-CROW L.A., CORNWELL T.L. Cornwell cGMP signaling through cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Adv. Pharmacol. 1995;34:305–322. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOHMANN S.M., VAANDRAGER A.B., SMOLENSKI A., WALTER U., DE JONGE R. Distinct and specific functions of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;22:307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKHLOUF G.M., GRIDER J.R. Nonadrenergic noncholinergic inhibitory neurotransmission of the gut. News Physiol. Sci. 1993;8:195–199. [Google Scholar]

- NY L., ANDERSSON K.E. Characterization of the NO/cyclic GMP system in the mouse gastric fundus. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1998;163:A25–A26. [Google Scholar]

- NY L., ALM P., LARSSON B., EKSTRÖM P., ANDERSSON K.E. Nitric oxide pathway in cat esophagus; localization of nitric oxide synthase and functional effects. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:G59–G70. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.1.G59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ÖGULENER N., KARABAL E., BAYSAL F., DIKMEN A. Possible roles of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide on relaxation induced by isoprenaline in isolated muscle strips of the mouse gastric fundus. Acta Med. Olcayama. 1995;49:231–236. doi: 10.18926/AMO/30401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEIFER A., ASZODI A., SEIDLER U., RUTH P., HOFMANN F., FÄSSLER R. Intestinal secretory defects and dwarfism in mice lacking cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase II. Science. 1996;274:2082–2086. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFEIFER A., KLATT P., MASSBERG S., NY L., SAUSBIER M., HIRNEISS C., WANG G., KORTH M., ASZODI A., ANDERSSON K.E., KROMBACH F., MAYERHOFER A., RUTH P., FÄSSLER R., HOFMANN F. Defective smooth muscle regulation in cyclic GMP-dependent kinase I-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1998;17:3045–3051. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDBERG M., NATARAJAN V., RONANDER I., KALDERON D., WALTER U., LOHMANN S.M., JAHNSEN T. Molecular cloning and predicted full-length amino acid sequence of the type I beta isozyme of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase from human placenta. Tissue distribution and developmental changes in rat. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:321–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDERS K.M., WARD S.M. Nitric oxide as a mediator of nonadrenergic noncholinergic neurotransmission. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:G379–G392. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.262.3.G379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANG Q., YOUNG H.M. Chemical coding of neurons in the myenteric plexus and external muscle of the small and large intestine of the mice. Cell Tissue Res. 1996;284:39–53. doi: 10.1007/s004410050565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUTTLEWORTH C.W., XUE C., WARD S.M., DE VENTE J., SANDERS K.M. Immunohistochemical localization of 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate in the canine proximal colon: responses to nitric oxide and electrical stimulation of enteric inhibitory neurons. Neuroscience. 1993;56:513–522. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90350-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STARK M.E., SZURSZEWSKI J.H. Role of nitric oxide in gastrointestinal and hepatic function and disease. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1928–1949. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91454-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UHLER M.D. Cloning and expression of a novel cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase from mouse brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:13586–13591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALDECK K., NY L., PERSSON K., ANDERSSON K.E. Mediators and mechanisms of relaxation in rabbit urethral smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:617–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALDMANN R., BAUER S., GOBEL C., HOFMANN F., JAKOBS K.H., WALTER U. Demonstration of cyclic GMP-dependent proteinkinase and cyclic GMP-dependent phosphorylation in cell-free extracts of platelets. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986;158:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WERNET W., FLOCKERZI V., HOFMANN F. The cDNA of the two isoforms of bovine cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOUNG H.M., MCCONALOGUE K., FURNESS J.B., DE VENTE J. Nitric oxide targets in the guinea-pig intestine identified by induction of cyclic GMP immunoreactivity. Neuroscience. 1993;55:583–596. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90526-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]