Abstract

Stimulation of the murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 with thapsigargin, an endomembrane Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor, induced histamine production in a time- and concentration-dependent manner.

The protein kinase C activator, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), also enhanced histamine production.

α-Fluoromethylhistidine, a suicide substrate of L-histidine decarboxylase (HDC), suppressed the thapsigargin (30 nM)- and TPA (30 nM)-induced histamine production.

Both thapsigargin (30 nM) and TPA (30 nM) induced phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAP kinase and p38 MAP kinase.

PD98059, a specific inhibitor of MEK-1 which phosphorylates p44/p42 MAP kinase, strongly suppressed both the thapsigargin (30 nM)- and TPA (30 nM)-induced histamine production, whereas SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38 MAP kinase, inhibited them only partially.

The other MEK-1 inhibitor, U-0126, also inhibited both the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production in a concentration-dependent manner.

Thapsigargin (30 nM) and TPA (30 nM) increased the levels of HDC mRNA at 4 h, but PD98059 suppressed both the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced increases in the HDC mRNA level.

These findings indicate that thapsigargin and TPA induce histamine production in RAW 264.7 cells by increasing the level of HDC mRNA, and that both the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production are regulated largely by p44/p42 MAP kinase and partially by p38 MAP kinase..

Keywords: Thapsigargin, TPA, histamine, L-histidine decarboxylase, p44/p42 MAP kinase, p38 MAP kinase, murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cell

Introduction

Histamine plays a variety of roles not only as an autacoid regulating the allergic inflammatory reaction (Beer et al., 1984; Falus & Meretey, 1992), the differentiation of leukocyte precursors (Nakaya & Tasaka, 1988) and the gastric acid secretion (Miyata et al., 1990), but also as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (Schwarts et al., 1980).

The biosynthesis of histamine from its precursor L-histidine is catalyzed by L-histidine decarboxylase (HDC) constitutively expressed in several types of cells, such as mast cells, basophils and enterochromaffin-like cells (Ding et al., 1997). In contrast, in macrophages, it has been reported that HDC expression is induced in response to various types of stimulation resulting in histamine production (Takamatsu & Nakano, 1994). In an allergic inflammation model in rats (Tsurufuji et al., 1982), we found that the antigen challenge induces a de novo synthesis of histamine due to the induction of HDC at the post-anaphylaxis phase (Hirasawa et al., 1989). In addition, the topical application of thapsigargin, an endomembrane Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor (Thastrup et al., 1990; 1994), or 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), a protein kinase C (PKC) activator (Nishizuka, 1992), on mouse skin induces an increase in HDC activity (Watanabe et al., 1981; 1982). Because the application of TPA on the skin of mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice also increases HDC activity in the skin, non-mast cells such as macrophages were suggested to produce histamine in vivo (Taguchi et al., 1982). However, the mechanisms of histamine production induced by thapsigargin or TPA in non-mast cells remain to be elucidated.

Thapsigargin and TPA induce various intracellular signalling events. One of the most important intracellular signalling events induced by these agents is the activation of MAP kinases (Nori et al., 1992; Thomas et al., 1992; Chao et al., 1997; El-Shemerly et al., 1997). So far, it has been demonstrated that MAP kinases are involved in various cellular responses including the production of various cytokines and chemical mediators (Rose et al., 1997; Bhat et al., 1998; Dumont et al., 1998; Egerton et al., 1998), and the induction of enzymes such as nitric oxide synthase (Badger et al., 1998). However, the involvement of MAP kinases in histamine production remains to be elucidated.

Recently, we found that thapsigargin and TPA induce histamine production in RAW 264.7 cells, an Abelson leukemia virus-transfected murine macrophage cell line (Raschke et al., 1978). Therefore, the aim of the present study is to clarify the mechanism of the de novo synthesis of histamine, especially focused on the involvement of MAP kinases, in TPA- and thapsigargin-induced histamine production in RAW 264.7 cells.

Methods

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells obtained from the RIKEN Gene Bank (Tsukuba, Japan) were maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C in Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM, Nissui Seiyaku, Tokyo, Japan) containing 1% (v v−1) MEM non-essential amino acid solution (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), 10% (v v−1) heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS, Flow Laboratories, Mclean, VA, U.S.A.), penicillin G potassium (18 μg ml−1) and streptomycin sulphate (50 μg ml−1) (Meiji Seika Co., Tokyo, Japan) in a 175 cm2 plastic tissue culture flask (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). When a confluent monolayer had developed, the cells were harvested using EDTA (0.02%, w v−1) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and suspended at 1.5×106 cells ml−1 in EMEM containing 10% (v v−1) heat-inactivated FBS (EMEM (+)). One milliliter of the cell suspension was seeded in each well of 12-well plastic tissue culture plates (Costar Co., Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.) and incubated for 20 h at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% air. After three washes with EMEM, the cells were incubated for the periods indicated at 37°C in 1 ml of EMEM (+) containing drugs.

Drug treatment

The drugs used were the endomembrane Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin (Wako Pure Chemicals Co., Osaka, Japan), the PKC activator TPA (Sigma Chemical Co.), the suicide substrate of HDC α-fluoromethylhistidine hydrochloride hemihydrate (α-FMH, a gift from Dr J. Kollonitsch, Merck Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ, U.S.A.), the MAP kinase-ERK kinase 1 (MEK-1) inhibitors PD98059 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, U.S.A.) and U0126 (Promega Co., Madison, WI, U.S.A.), and the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Co., San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Thapsigargin and TPA were dissolved in ethanol, α-FMH was dissolved in water and PD98059, U0126 and SB203580 were dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO). The final concentrations of ethanol and DMSO were adjusted to 0.1% (v v−1), and the control medium contained the same amount of the vehicle.

Determination of histamine contents

After incubation, the conditioned medium was collected and centrifuged at 220×g and 4°C for 3 min. The histamine contents in the supernatant fraction of the conditioned medium were determined fluorometrically as described by Shore et al. (1959). To determine the histamine contents in the cells, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS after incubation, and added with 1 ml PBS. The cells were then sonicated using a Handy Sonic Disruptor (Tomy, Tokyo, Japan) (a half maximum power, 5 s, three times), centrifuged at 220×g and 4°C for 3 min, and histamine contents in the supernatant fraction was determined.

Western blot analysis

Two milliliter-aliquots of the cell suspension (1.5×106 cells ml−1) were seeded into a plastic dish (35 mm diameter, Corning, Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.) and incubated for 20 h at 37°C. After three washes with EMEM, the cells were further incubated for the periods indicated at 37°C in 2 ml of EMEM (+) containing the indicated concentrations of drugs. After incubation, the cells were washed and lysed in 150 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (HEPES 20 mM, pH 7.3, Triton X-100 1% (v v−1), EDTA 1 mM, NaF 50 mM, p-nitrophenylphosphate 2.5 mM, Na3VO4 1 mM, leupeptin 10 μg ml−1 and glycerol 10% (v v−1)). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000×g and 4°C for 20 min, and 120 μl of the supernatant fractions were obtained. The protein concentrations in the supernatant fractions were determined according to the method described by Lowry et al. (1951) and were adjusted to 2 μg μl−1 of the lysis buffer. Sixty microliters of the loading buffer (Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4, sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) 4% (w v−1), glycerol 10% (v v−1), 2-mercaptoethanol 4% (v v−1) and bromophenol blue 50 μg ml−1) was added to the cell lysates and the cell lysates were boiled for 3 min. Aliquots of 10 μl of the solution were applied to each well of a 3% (w v−1) stacking SDS-polyacrylamide gel in 0.25 M Tris-glycine buffer (pH 6.8) and subjected to electrophoresis in 10% (w v−1) SDS-polyacrylamide gel in 1.5 M Tris-glycine (pH 8.8) at 125 V for 3 h. The fractionated proteins were transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell GmbH, Dassel, Germany) in transfer buffer (Tris-HCl 20 mM, pH 8.3, glycine 150 mM and methanol 20% (v v−1)) at 150 mA for 1 h at room temperature. After the transfer, non-specific sites on the membranes were blocked with blocking solution (Block Ace, Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan) for 3 h. The nitrocellulose membranes were then incubated at 4°C overnight with the primary antibody, rabbit IgG to phospho-p44/p42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204) (New England Biolabs), or to phospho-specific p38 MAP kinase (Thr180/Tyr182) (New England Biolabs) at a dilution of 1 : 1000. After washing, the membranes were incubated for 3 h at 4°C with the secondary antibody, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.), and then incubated for 1 h at 4°C with peroxidase-conjugated avidin-biotin-complex (Vectastatin ABC reagent, Vector Laboratories). The recognized proteins were visualized by using a chemiluminescence detection system (ECL system, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.). The membranes were exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, U.S.A.) at room temperature for 30 s and then developed.

The membranes were then incubated for 30 min at 50°C in a stripping buffer (Tris-HCl 60 mM, pH 6.7, SDS 70 mM and 2-mercaptoethanol 0.7% (v v−1)) to strip the used antibodies off the membranes. After incubation, the membranes were blocked with blocking solution, and then an immunoblot reaction was performed using the primary antibody, anti-rat MAP kinase R2 (Erkl-CT) [42–44 kDa] antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.), or p38 (C-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.), followed by the secondary antibody, alkaline phosphatase-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.) as described above. An alkaline phosphatase reaction was then carried out using nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate solution (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) as a substrate.

Determination of the mRNA levels of HDC by the reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) method

Ten milliliter-aliquots of the cell suspension (1.5×106 cells ml−1) were seeded into a plastic dish (100 mm diameter, Corning), two dishes per group and incubated for 20 h at 37°C. After three washes with EMEM, the cells were further incubated for the periods indicated at 37°C in 10 ml of EMEM (+) containing drugs.

Following the incubation, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and scraped off the plate with a rubber policeman. Total RNA in the cells was extracted by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction (Chomczynski & Sacchi, 1987), and the yield of RNA extracted was determined by spectrophotometry. One microgram of RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed at 37°C for 1 h in 40 μl of the buffer (Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 8.3, KCl 75 mM and MgCl2 3 mM) containing 5 μM of random hexamer oligonucleotides (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.), 200 U of the reverse-transcriptase from moloney murine leukaemia virus (Gibco BRL), 0.5 μM deoxynucleotide 5′-triphosphate and 10 mM dithiothreitol. PCR primers for murine HDC were designed according to Yamamoto et al. (1990). The sequences of primers used were; (former) 5′- GGATCCAAGATCAGATTTCTACCTGTGGAC-3′ and (reverse), 5′- GTCGACGACATGTGCTTGAAGATTCTTCAC-3′, which amplify a 516-HDC base pair (bp) fragment. PCR was performed for 30 cycles in 50 μl of the PCR buffer (Tris-HCl 10 mM, pH 8.3, KCl 50 mM and MgCl2 1.5 mM) containing 5 μl of the synthesized cDNA solution, 0.25 μM each primer, 125 μM dNTP and 0.5 U Taq polymerase (Takara Shuzo Co., Ohtsu, Shiga, Japan) using a thermal cycler (GeneAmp™ PCR System 2400, Perkin Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT, U.S.A.). Each cycle consisted of 0.5 min denaturation at 94°C, 1 min annealing at 56°C, and 2 min extension at 72°C. The murine glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene (a housekeeping gene) was used as an internal standard gene. The PCR primers for murine GAPDH were described by Robbins & McKinney (1992). The sequences of primers used were; (former) 5′- TGATGACATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAG-3′ and (reverse) 5′- TCCTTGGAGGCCATGTAGGCCAT-3′, which amplify a 249-GAPDH bp fragment. PCR was performed for 27 cycles; 0.5 min denaturation at 94°C, 1 min annealing at 57°C, and 2 min extension at 72°C. The other conditions were the same as those for murine HDC. After the PCR was performed, 9 μl of the PCR reaction mixture was loaded onto a 1.5% (w v−1) agarose gel, and the PCR products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining after electrophoresis.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the results was analysed by Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons and Student's t-test for unpaired observations. The data indicated are the means from three independent experiments with s.e.mean.

Results

Increase in histamine production and the HDC mRNA levels in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated with thapsigargin

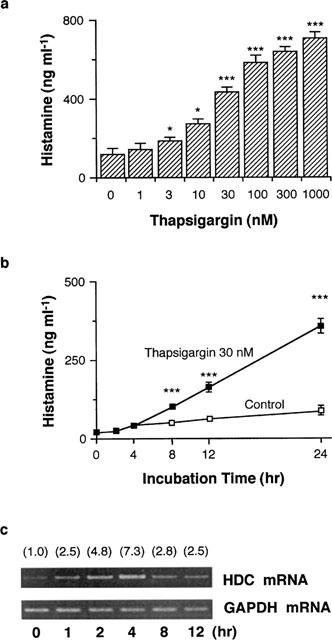

Incubation of RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×106 cells) in EMEM (+) containing various concentrations of thapsigargin for 24 h increased histamine contents in the conditioned medium in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1a). Because the incubation with thapsigargin at concentrations more than 100 nM for 24 h induced morphological changes and floatation of RAW 264.7 cells from the dishes, thapsigargin was used at a concentration of 30 nM in the subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Effects of thapsigargin on histamine production and HDC mRNA levels in RAW 264.7 cells. (a) RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×106 cells) were incubated for 24 h in EMEM (+) containing the indicated concentrations of thapsigargin. Histamine contents in the conditioned medium were measured as described in Methods. Values are the means from three independent experiments with s.e.mean shown by vertical bars. Statistical significance; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs 0 nM thapsigargin. (b) RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×106 cells) were incubated for the periods indicated in EMEM (+) in the presence or absence of 30 nM thapsigargin. Histamine contents in the conditioned medium were measured as described in Methods. Values are the means from three independent experiments with s.e.mean shown by vertical bars. Statistical significance; ***P<0.001 vs corresponding control. The results were confirmed by repeating two independent sets of experiments. (c) RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×107 cells) were stimulated with 30 nM thapsigargin for the periods indicated. Total RNA was extracted and RT–PCR was performed as described in Methods. Numbers in parentheses indicate the ratio of HDC mRNA density to GAPDH mRNA density. The density ratio at time 0 h is set to 1.0. The results were confirmed by repeating two independent sets of experiments.

When the cells were incubated in the presence of 30 nM thapsigargin, the histamine contents in the conditioned medium were increased time-dependently, and significantly increased from 8 h after incubation compared with those in the corresponding non-stimulated cells (Figure 1b). The histamine contents in the conditioned medium at 0 h were 19.0±1.2 ng ml−1, reflecting histamine in FBS in the medium. In contrast, the histamine contents in the cells (10.2±2.1 ng/106 cells in unstimulated group) were not increased in the presence or absence of 30 nM thapsigargin.

By treatment with 30 nM thapsigargin, the HDC mRNA levels in the cells were increased time-dependently, reaching a maximum at 4 h, and declined at 8 h (Figure 1c). In contrast, the GAPDH mRNA levels were constant during the incubation period (Figure 1c). Incubation of the cells in the absence of thapsigargin did not increase the HDC mRNA levels (data not shown).

Effects of TPA on histamine production in RAW 264.7 cells

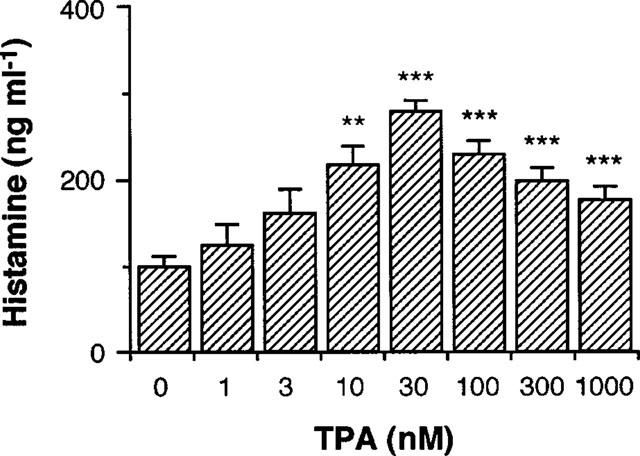

When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated in the presence of various concentrations of TPA for 24 h, the histamine contents in the conditioned medium were increased with a maximum effect at 30 nM (Figure 2). In the subsequent experiments, TPA was used at a concentration of 30 nM.

Figure 2.

Effects of TPA on histamine production by RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×106 cells) were incubated for 24 h in EMEM (+) containing the indicated concentrations of TPA. The histamine contents in the conditioned medium were measured as described in Methods. Values are the means from three independent experiments with s.e.mean shown by vertical bars. Statistical significance; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs 0 nM TPA.

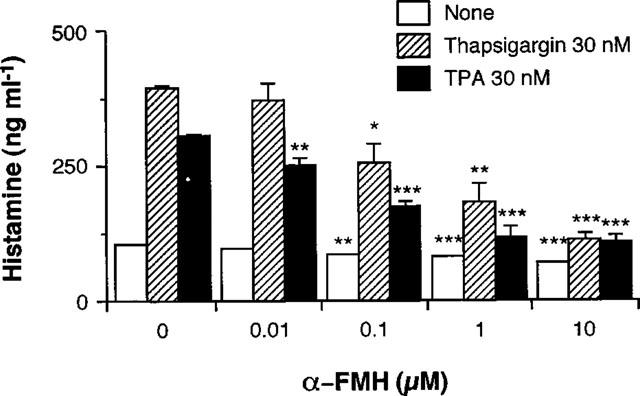

Effects of α-FMH on thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production in RAW 264.7 cells

To clarify whether increase in the histamine contents in the conditioned medium of thapsigargin- and TPA-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells is due to the de novo synthesis of histamine, the effects of α-FMH, an inhibitor of HDC, on the increase in histamine contents in the conditioned medium were examined. As shown in Figure 3, α-FMH suppressed the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced increase in histamine contents in the conditioned medium at 24 h in a concentration-dependent manner. Spontaneous increase in histamine contents in the conditioned medium was also suppressed by α-FMH at concentrations more than 0.1 μM.

Figure 3.

Effects of α-FMH on histamine production by RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×106 cells) were incubated for 24 h in EMEM (+) containing the indicated concentrations of α-FMH in the absence or presence of 30 nM thapsigargin or 30 nM TPA. Histamine contents in the conditioned medium were measured as described in Methods. Values are the means from three independent experiments with s.e.mean shown by vertical bars. Statistical significance; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs corresponding 0 μM α-FMH.

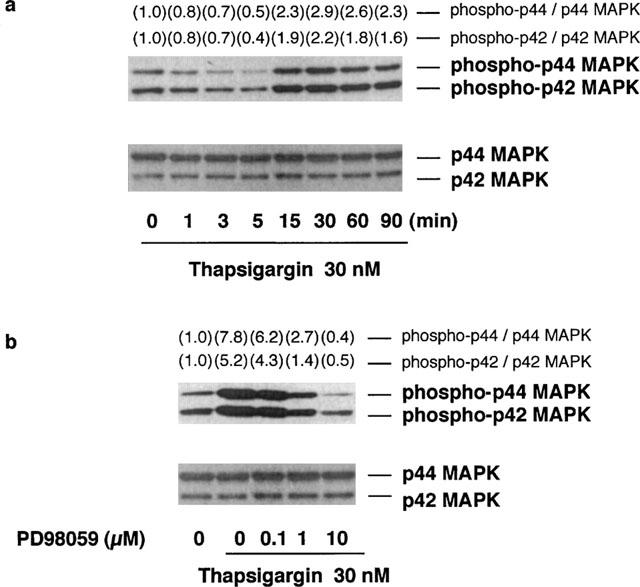

Phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAP kinase by thapsigargin and its inhibition by PD98059

When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated at 37°C in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM thapsigargin, the phosphorylation levels of p44/p42 MAP kinase decreased from 1–5 min, but increased at 15 min and then declined at 90 min (Figure 4a, upper), whereas the p44/p42 MAP kinase protein levels were constant during the incubation period (Figure 4a, lower).

Figure 4.

Time course of thapsigargin-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation and the effects of PD98059 on thapsigargin-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation. (a) RAW 264.7 cells (3.0×106 cells) were incubated for the periods indicated in EMEM (+) in the presence of 30 nM thapsigargin. (b) RAW 264.7 cells (3.0×106 cells) were incubated for 15 min in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM thapsigargin and the indicated concentrations of PD98059. The cells were lysed and the p44/p42 MAP kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation levels were analysed by Western blot as described in Methods. Numbers in parentheses indicate the fold increase in phospho-p44 and p42 MAPK as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of unstimulated control is set to 1.0. The results were confirmed by repeating two independent sets of experiments.

The effects of PD98059, a specific inhibitor of MEK-1, on the thapsigargin-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation levels were then determined, because the phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAP kinase is dependent on the activity of MEK-1. When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of 30 nM thapsigargin and the indicated concentrations of PD98059, the thapsigargin-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4b, upper), while the protein levels of p44/p42 MAP kinase were not changed by PD98059 (Figure 4b, lower). These findings indicated that PD98059 blocks the MEK-1–p44/p42 MAP kinase cascade in thapsigargin-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells.

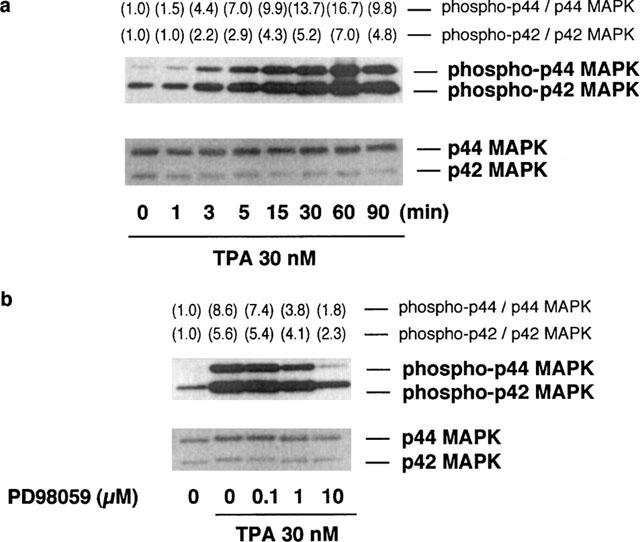

Phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAP kinase by TPA and its inhibition by PD98059

When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated at 37°C in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM TPA, the phosphorylation levels of p44/p42 MAP kinase began to increase at 3 min and attained a plateau at 15 min (Figure 5a, upper), whereas the p44/p42 MAP kinase protein levels were constant during the incubation period (Figure 5a, lower).

Figure 5.

Time course of TPA-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation and the effects of PD98059 on TPA-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation. (a) RAW 264.7 cells (3.0×106 cells) were incubated for the periods indicated in EMEM (+) in the presence of 30 nM TPA. (b) RAW 264.7 cells (3.0×106 cells) were incubated for 15 min in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM TPA and the indicated concentrations of PD98059. The cells were lysed and the p44/p42 MAP kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation levels were analysed by Western blot as described in Methods. Numbers in parentheses indicate the fold increase in phospho-p44 and p42 MAPK as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of unstimulated control is set to 1.0. The results were confirmed by repeating two independent sets of experiments.

The effects of PD98059 on the TPA-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation were then determined. When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM TPA and the indicated concentrations of PD98059, the TPA-induced phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAP kinase was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5b, upper). The protein levels of p44/p42 MAP kinase were constant during the incubation period (Figure 5b, lower).

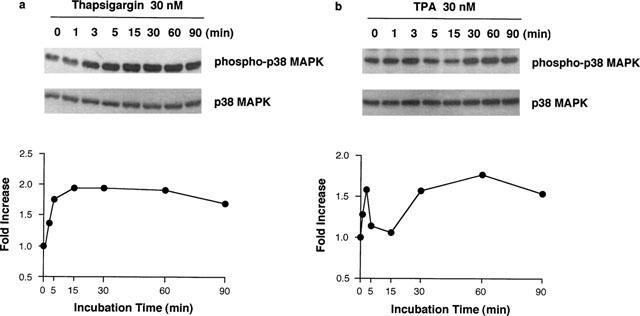

Phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase by thapsigargin and TPA

When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated at 37°C in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM thapsigargin, the phosphorylation levels of p38 MAP kinase began to increase at 3 min, reaching a maximum level at 30 min, and declined at 90 min (Figure 6a). In contrast, stimulation of RAW 264.7 cells with 30 nM TPA increased phosphorylation levels of p38 MAP kinase at 3 and 60 min, biphasically (Figure 6b). The p38 MAP kinase protein levels were constant during the incubation period in both experimental conditions.

Figure 6.

Time course of thapsigargin- and TPA-induced p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation. RAW 264.7 cells (3.0×106 cells) were incubated for the periods indicated in EMEM (+) in the presence of 30 nM thapsigargin (a) or TPA (b). The cells were lysed and the p38 MAP kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation levels were analysed by Western blot as described in Methods. The results were confirmed by repeating two independent sets of experiments. The changes of the density ratio of phospho-p38 MAPK to p38 MAPK are shown in the lower panel. The density ratio at time 0 min is set to 1.0.

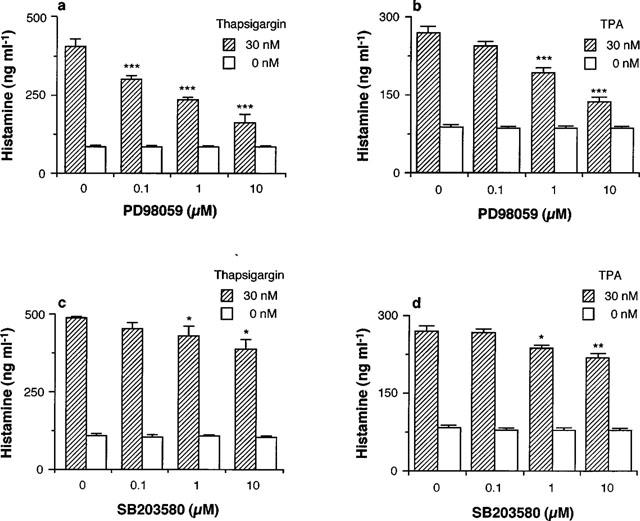

Effects of PD98059 and SB203580 on thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production in RAW 264.7 cells

When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in EMEM (+) containing the indicated concentrations of PD98059 in the presence or absence of 30 nM thapsigargin or TPA, PD98059 suppressed both the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced increase in histamine contents in the conditioned medium at 0.1–10 μM (Figure 7a,b).

Figure 7.

Effects of PD98059 and SB203580 on thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production by RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×106 cells) were incubated for 24 h in EMEM (+) containing the indicated concentrations of PD98059 (a,b) or SB203580 (c,d) in the presence or absence of 30 nM thapsigargin (a,c) or TPA (b,d). The histamine contents in the conditioned medium were measured as described in Methods. Values are the means from three independent experiments with s.e.mean shown by vertical bars. Statistical significance; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs corresponding 0 μM PD98059 or SB203580.

The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 also suppressed both the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production, but the inhibitory effects of SB203580 were much weaker than those of PD98059 (Figure 7c,d).

In contrast, PD98059 and SB203580 did not suppress the spontaneous increase in histamine contents in the conditioned medium, even at the highest concentration (10 μM) (Figure 7a–d).

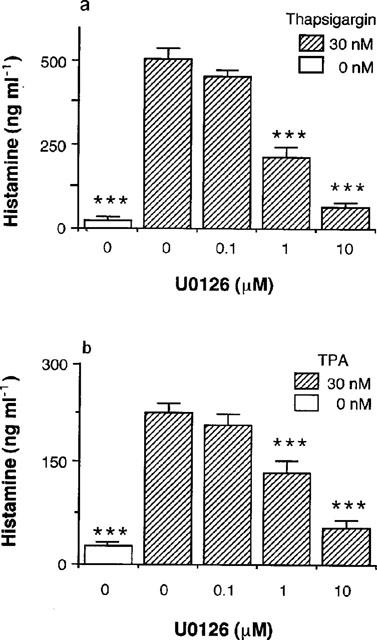

Effects of U0126 on thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production

To confirm the involvement of p44/p42 MAP kinase in thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production in RAW 264.7 cells, the other MEK-1 inhibitor U0126 was used. As shown in Figure 8, U0126 inhibited both thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 8.

Effects of U0126 on thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production. RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×106 cells) were incubated for 24 h in EMEM (+) containing the indicated concentrations of U0126 in the presence or absence of 30 nM thapsigargin (a) or TPA (b). The histamine contents in the conditioned medium were measured as described in Methods. Values are the means from three independent experiments with s.e.mean shown by vertical bars. Statistical significance; ***P<0.001 vs corresponding 0 μM U0126.

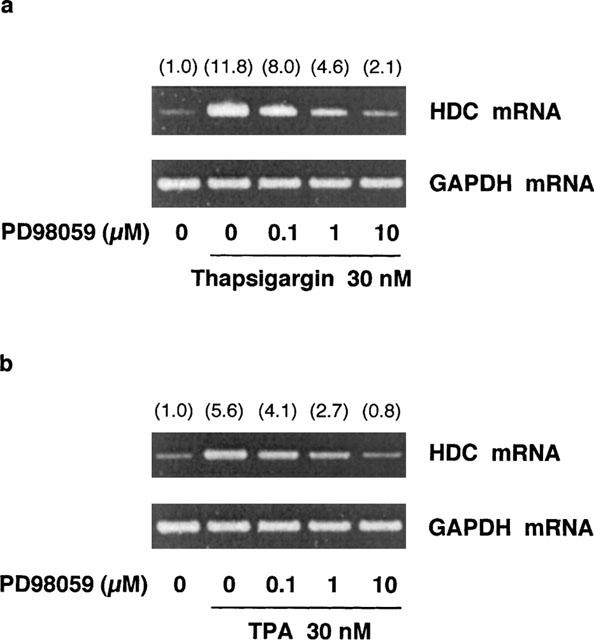

Effects of PD98059 on thapsigargin-induced and TPA-induced increases in HDC mRNA levels in RAW 264.7 cells

When RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM thapsigargin or TPA and the indicated concentrations of PD98059, the thapsigargin- or TPA-induced increase in HDC mRNA levels was suppressed by PD98059 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 9a,b). In contrast, the GAPDH mRNA levels were constant during the incubation period.

Figure 9.

Effects of PD98059 on thapsigargin- and TPA-induced increase in HDC mRNA levels in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells (1.5×107 cells) were incubated for 4 h in EMEM (+) containing 30 nM thapsigargin (a) or TPA (b) and the indicated concentrations of PD98059. Total RNA was extracted and RT-PCR was performed as described in Methods. Numbers in parentheses indicate the ratio of HDC mRNA density to GAPDH mRNA density. The density ratio of unstimulated control is set to 1.0. The results were confirmed by repeating two independent sets of experiments.

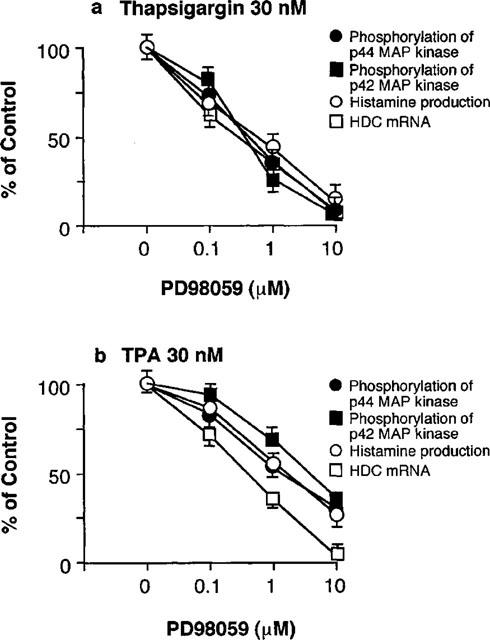

As summarized in Figure 10, the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAP kinase was decreased by PD98059 in parallel with the decrease in histamine production and HDC mRNA levels.

Figure 10.

Summary of the inhibitory effects of PD98059 on thapsigargin- and TPA-induced responses. The effects on the phosphorylation of p44 and p42 MAP kinase shown in Figures 5 and 6, and on HDC mRNA levels in Figure 9 were quantified by densitometric analysis and compared with those on the histamine production in Figure 7. The control values obtained by 0 μM PD98059 are expressed as 100%. Each symbol represents the mean of three independent experiments with s.e.mean shown by vertical bars.

Discussion

Thapsigargin and TPA at very low concentrations induce arachidonic acid release, the production of prostaglandin (PG) E2, platelet-activating factor (PAF) and various cytokines in rat peritoneal macrophages (Ohuchi et al., 1988; Watanabe et al., 1995; Yamada et al., 1998). In the present study, we found that thapsigargin and TPA also increase histamine contents in the conditioned medium of RAW 264.7 cells (Figures 1a,b and 2). We suggested that the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced increases in histamine contents in the conditioned medium are due not to the release of preformed histamine but to the leakage of de novo produced histamine, based on the following three findings. First, the histamine contents in the non-stimulated cells were low and were not changed during the incubation period, while the histamine contents in the conditioned medium of thapsigargin-treated cells were increased time-dependently (Figure 1b). Second, thapsigargin and TPA both increased the HDC mRNA levels with a maximum at 4 h (Figure 1c and 9). And third, α-FMH suppressed the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production (Figure 3). RAW 264.7 cells have been widely used to analyse the regulation mechanism of arachidonate metabolism (Lin & Chen, 1998; Lin et al., 1998) and nitric oxide production (Yamashita et al., 1997). However, the present study is the first report that RAW 264.7 cells produce histamine following stimulation with thapsigargin or TPA.

Stimulation with thapsigargin or TPA commonly induces the activation of various protein kinases, including MAP kinase (Nori et al., 1992; Thomas et al., 1992; Chao et al., 1997; El-Shemerly et al., 1997). MAP kinase is a key enzyme in the signal transduction of inflammatory reactions, such as the production of cytokines (Rose et al., 1997; Bhat et al., 1998; Matsumoto et al., 1998), arachidonic acid release (Zhang et al., 1997) and the function of the cells responsible for inflammation (Zu et al., 1998). In the present study, two kinds of MEK-1 inhibitors, PD98059 (Alessi et al., 1995; Dudley et al., 1995) and U0126 (Favata et al., 1998), inhibited histamine production by thapsigargin- and TPA-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells (Figures 7 and 8), indicating that p44/p42 MAP kinase is involved in histamine production. In addition, because PD98059 inhibited the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced increase in HDC mRNA levels in parallel with the inhibition of p44/p42 MAP kinase activation (Figure 10), it is strongly suggested that p44/p42 MAP kinase regulates HDC expression at the transcriptional level in RAW 264.7 cells. Höcker et al. (1997) reported that in the gastric carcinoma cell line AGS-B, the p44/p42 MAP kinase pathway is essential for the gastrin- and TPA-induced transcriptional activity of the human HDC gene promoter. Thus, the involvement of p44/p42 MAP kinase in HDC induction might be common among types of cells that produce histamine. The down-stream of p44/p42 MAP kinase for the expression of HDC gene is still unknown. However, it is reported that one of the putative transcription factors responsible for HDC gene expression is NF-IL6 (Ohtsu et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 1996), which is known to be phosphorylated by p44/p42 MAP kinase (Nakajima et al., 1993). Further investigations are necessary to clarify the transcription factors involved in the transcription of HDC gene.

Thapsigargin induces an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels by inhibiting Ca2+-ATPase (Thastrup et al., 1990; 1994), but TPA activates PKC directly (Nishizuka, 1992). However, it is known that both thapsigargin and TPA activate p44/p42 MAP kinase (Nori et al., 1992; Thomas et al., 1992; Chao et al., 1997; El-Shemerly et al., 1997). Generally, the thapsigargin-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase activation is mediated by the tyrosine kinase Src and the serine-threonine kinase Raf-1 signalling pathways, which are Ca2+-dependent (Chao et al., 1997), while the TPA-induced p44/p42 MAP kinase activation is mediated by PKC and Ras signalling pathways which are Ca2+-independent (Nori et al., 1992; Thomas et al., 1992; El-Shemerly et al., 1997). The Ca2+-independent activation of p44/p42 MAP kinase is faster than the Ca2+-dependent activation (Chao et al., 1992); this is consistent with our present findings (Figures 4a and 5a). On the other hand, the decrease of p44/p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation levels from 1–5 min on stimulation with thapsigargin might be due to phosphatase activation. Thus, although the activation pathways of p44/p42 MAP kinase are different between thapsigargin and TPA, both the agents activate p44/p42 MAP kinase, and the activation of p44/p42 MAP kinase is a common and an essential step for the induction of HDC.

The inhibition by SB203580 (Lee et al., 1994; Cuenda et al., 1995) of the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production was less than that by PD98059 (Figure 7). The IC50 value of SB203580 for p38 MAP kinase activity is 0.6 μM (Cuenda et al., 1995), and 10 μM of SB203580 effectively inhibits interleukin (IL)-1α-, tumour necrosis factor-α- and PAF-induced IL-8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells (Matsumoto et al., 1998). In addition, lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthesis by RAW 264.7 cells is also inhibited by SB203580 (IC50⩽5 μM) (Chen & Wang, 1999). Therefore, the concentrations of SB203580 in the present study seemed to be enough to inhibit p38 MAP kinase activity. The weak inhibition by SB203580 of the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced histamine production indicated that p38 MAP kinase is partially involved in HDC induction in RAW 264.7 cells.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the stimulation of RAW 264.7 cells with thapsigargin or TPA induces a continuous histamine production via the de novo synthesis of HDC, and that both the thapsigargin- and TPA-induced increase in the HDC mRNA level are regulated mainly by p44/p42 MAP kinase and partially by p38 MAP kinase.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr J. Kollonitsch, Merck Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ, U.S.A., for the generous supply of α-FMH hydrochloride hemihydrate. This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for General Scientific Research (09672211), Exploratory Research (11877381) and Scientific Research (B) (11470481) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Abbreviations

- FMH

fluoromethylhistidine

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HDC

L-histidine decarboxylase

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- MEK

MAP kinase-ERK kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate

References

- ALESSI D.R., CUENDA A., COHEN P., DUDLEY D.T., SALTIEL A.R. (PD 098059) is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BADGER A.M., COOK M.N., LARK M.W., NEWMAN-TARR T.M., SWIFT B.A., NELSON A.H., BARONE F.C., KUMAR S. SB 203580 inhibits p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, nitric oxide production, and inducible nitric oxide synthase in bovine cartilage-derived chondrocytes. J. Immunol. 1998;161:467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEER D.J., MATLOFF S.M., ROCKLIN R.E. The influence of histamine on immune and inflammatory responses. Adv. Immunol. 1984;35:209–268. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHAT N.R., ZHANG P., LEE J.C., HOGAN E.L. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 subgroups of mitogen-activated protein kinases regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor-α gene expression in endotoxin-stimulated primary glial cultures. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1633–1641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01633.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAO T.-S.O., ABE M., HERSHENSON M.B., GOMES I., ROSNER M.R. Srk tyrosine kinase mediates stimulation of Raf-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase by the tumor promoter thapsigargin. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3168–3173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAO T.-S.O., BYRON K.L., LEE K.-M., VILLEREAL M., ROSNER M.R. Activation of MAP kinases by calcium-dependent and calcium-independent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:19876–19883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN C.-C., WANG J.-K. p38 but not p44/42 Mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for nitoric oxide synthase induction mediated by lipopolysaccharide in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:481–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOMCZYNSKI P., SACCHI N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUENDA A., ROUSE J., DOZA Y.N., MEIER R., COHEN P., GALLAGHER T.F., YOUNG P.R., LEE J.C. SB203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DING X.Q., LINSTROM E., HAKANSON R. Time-course of deactivation of rat stomach ECL cells following cholecystokinin B/gastrin receptor blockade. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUDLEY D.T., PANG L., DECKER S.J., BRIDGES A.J., SALTIEL A.R. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMONT F.J., STARUCH M.J., FISCHER P., DASILVA C., CAMACHO R. Inhibition of T cell activation by pharmacologic disruption of the MEK1/ERK MAP kinase or calcineurin signaling pathways results in differential modulation of cytokine production. J. Immunol. 1998;160:2579–2589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGERTON M., FITZPATRICK D.R., KELSO A. Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway is differentially required for TCR-stimulated production of six cytokines in primary T lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 1998;10:223–229. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EL-SHEMERLY M.Y.M., BESSER D., NAGASAWA M., NAGAMINE Y. 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate activates the Ras/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway upstream of SOS involving serine phosphorylation of Shc in NIH3T3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30599–30602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FALUS A., MERETEY K. Histamine: an early messenger in inflammatory and immune reactions. Immunol. Today. 1992;13:154–156. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90117-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAVATA M.F., HORIUCHI Y., MANOS E.J., DAULERIO A.J., STRADLEY D.A., FEESER W.S., VAN DYK D.E., PITTS W.J., EARL R.A., HOBBS F., COPELAND R.A., MAGOLDA R.L., SCHRLE P.A., TRZASKOS J.M. Identification a novel inhibitor of migoten-activated protein kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRASAWA N., OHUCHI K., KAWARASAKI K., WATANABE M., TSURUFUJI S. Occurrence of histamine-production-increasing factor in the postanaphylactic phase of allergic inflammation. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1989;88:386–393. doi: 10.1159/000234722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HÖCKER M., HENIHAN R.J., ROSEWICZ S., RIECKEN E.-O., ZHANG Z., KOH T.J., WANG T.C. Gastrin and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate regulate the human histidine decarboxylase promoter through Raf-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-related signaling pathways in gastric cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27015–27024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE J.C., LAYDON J.T., MCDONNELL P.C., GALLAGHER T.F., KUMAR S., GREEN D., MCNULTY D., BLUMENTHAL M.J., HEYS J.R., LANDVATTER S.W., STRICKLER J.E., MCLAUGHLIN M.M., SIEMENS I.R., FISHER S.M., LIVI G.P., WHITE J.R., ADAMS J.L., YOUNG P.R. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN W.W., CHANG S.-H., WU M.-L. Lipoxygenase metabolites as mediators of UTP-induced intracellular acidification in mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:313–321. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN W.W., CHEN B.C. Pharmacological comparison of UTP- and thapsigargin-induced arachidonic acid release in mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1173–1181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O.H., ROSEBROUGH N.J., FARR A.L., RANDALL R.J. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUMOTO K., HASHIMOTO S., GON Y., NAKAYAMA T., HORIE T. Proinflammatory cytokine-induced and chemical mediator-induced IL-8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1998;101:825–831. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYATA K., KAMATO T., FUJIHARA A., TAKEDA M. Selective and competitive histamine H2-receptor blocking effect of famotidine on the blood pressure response in dogs and the acid secretory response in rats. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1990;54:197–204. doi: 10.1254/jjp.54.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAJIMA T., KINOSHITA S., SASAGAWA T., NARUTO M., KISHIMOTO T., AKIRA S. Phosphorylation at threonine-235 by a ras-dependent mitogen-activating protein kinase cascade is essential for transcription factor NF-IL6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:2207–2211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAYA N., TASAKA K. The influence of histamine on precursors of granulocytic leukocytes in murine bone marrow. Life Sci. 1988;42:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIZUKA Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORI M., L'ALLEMAIN G., WEBER M.J. Regulation of tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate-induced responses in NIH3T3 cells by GAP, the GTPase-activating protein associated with p21c-ras. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:936–945. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHTSU H., KURAMASU A., SUZUKI S., IGARASHI K., OHUCHI Y., SATO M., TANAKA S., NAKAGAWA S., SHIRATO K., YAMAMOTO M., ICHIKAWA A., WATANABE T. Histidine decarboxylase expression in mouse mast cell line P815 is induced by mouse peritoneal cavity incubation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:28439–28444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHUCHI K., SUGAWARA T., WATANABE M., HIRASAWA N., TSURUFUJI S., FUJIKI H., CHRISTENSEN S.B., SUGIMURA T. Analysis of the stimulative effect of thapsigargin, a non-TPA-type tumour promoter, on arachidonic acid metabolism in rat peritoneal macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;94:917–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RASCHKE W.C., BAIRD S., RALPH P., NAKOINZ I. Functional macrophage cell lines transformed by Abelson leukemia virus. Cell. 1978;15:261–267. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBBINS M., MCKINNEY M. Transcriptional regulation of neuromodulin (GAP-43) in mouse neuroblastoma clone N1E-115 as evaluated by the RT/PCR method. Mol. Brain Res. 1992;13:83–92. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90047-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSE D.M., WINSTON B.W., CHAN E.D., RICHES D.W.H., GERWINS P., JOHNSON G.L., HENSON P.M. Fcγ receptor cross-linking activates p42, p38, and JNK/SAPK mitogen-activated protein kinases in murine macrophages. Role for p42MAPK in Fcγ receptor-stimulated TNF-α synthesis. J. Immunol. 1997;158:3433–3438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTS J.C., POLLARD H., QUACH T.T. Histamine as a neurotransmitter in mammalian brain: neurochemical evidence. J. Neurochem. 1980;35:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb12485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHORE P.A., BURKHALTER A., COHN V.H. A method for the fluorometric assay of histamine in tissues. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1959;127:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAGUCHI Y., TSUYAMA K., WATANABE T., WADA H., KITAMURA Y. Increase in histidine decarboxylase activity in skin of genetically mast-cell-deficient W/Wv mice after application of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate: Evidence for the presence of histamine-producing cells without basophilic granules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1982;79:6837–6841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.22.6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAMATSU S., NAKANO K. Histamine synthesis by bone marrow-derived macrophages. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 1994;58:1918–1919. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THASTRUP O., CULLEN P.J., DROBAK B.K. , HANLEY M.R., DAWSON A.P. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THASTRUP O., DAWSON A.P., SCHARFF O., FODER B., CULLEN P.J., DRØBAK B.K., BJERRUM P.J., CHRISTENSEN S.B., HANLEY M.R. Thapsigargin, a novel molecular probe for studying intracellular calcium release and storage. Agents Actions. 1994;43:187–193. doi: 10.1007/BF01986687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS S.M., DEMARCO M., D'ARCANGELO G., HALEGOUA S., BRUGGE J.S. Ras is essential for nerve growth factor- and phorbol ester-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of MAP kinases. Cell. 1992;68:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90075-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSURUFUJI S., YOSHINO S., OHUCHI K. Induction of an allergic air-pouch inflammation in rats. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1982;69:189–198. doi: 10.1159/000233170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE M., YAMADA M., MUE S., OHUCHI K. Enhancement by cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors of platelet-activating factor production in thapsigargin-stimulated macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2141–2147. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE T., TAGUCHI Y., KITAMURA Y., TSUYAMA K., FUJIKI H., TANOOKA H., SUGIMURA T. Induction of histidine decarboxylase activity in mouse skin after application of indole alkaloids, a new class of tumor promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982;109:478–485. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE T., TAGUCHI Y., SASAKI K., TSUYAMA K., KITAMURA Y. Increase in histidine decarboxylase activity in mouse skin after application of the tumor promoter tetradecanoylphorbol acetate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1981;100:427–432. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(81)80114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA M., ICHINOWATARI G., TANIMOTO A., YAGINUMA H., OHUCHI K. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α production by SK&F98625, a CoA-independent transacylase inhibitor, in cultured rat peritoneal macrophages. Life Sci. 1998;62:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO J., YATSUNAMI K., OHMORI E., SUGIMOTO Y., FUKUI T., KATAYAMA T., ICHIKAWA A. cDNA-derived amino acid sequence of L-histidine decarboxylase from mouse mastocytoma P-815 cells. FEBS Lett. 1990;276:214–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80545-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMASHITA M., NIKI H., YAMADA M., MUE S., OHUCHI K. Induction of nitric oxide synthase by lipopolysaccharide and its inhibition by auranofin in RAW 264.7 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;338:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)81943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG C., BAUMGARTNER R.A., YAMADA K., BEAVEN M.A. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase regulates production of tumor necrosis factor-α and release of arachidonic acid in mast cells. Indications of communication between p38 and p42 MAP kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13397–13402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG Z., HÖCKER M., KOH T.J., WANG T.C. The human histidine decarboxylase promoter is regulated by gastrin and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate through a downstream cis-acting element. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:14188–14197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZU Y.-L., QI J., GILCHRIST A., FERNANDEZ G.A., VAZQUEZ-ABAD D., KREUTZER D.L., HUANG C.-K., SHA'AFI R.I. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is required for human neutrophil function triggered by TNF-α or FMLP stimulation. J. Immunol. 1998;160:1982–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]