Abstract

The effects of ethanol on the function of recombinant glycine transporter 1 (GLYT1) and glycine transporter 2 (GLYT2) have been investigated.

GLYT1b and GLYT2a isoforms stably expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells showed a differential behaviour in the presence of ethanol; only the GLYT2a isoform was acutely inhibited.

The ‘cut-off' (alcohols with four carbons) displayed by the n-alkanols on GLYT2a indicates that a specific binding site for ethanol exists on GLYT2a or on a GLYT2a-interacting protein.

The non-competitive inhibition of GLYT2a indicates an allosteric modulation by ethanol of GLYT2a activity.

Chronic treatment with ethanol caused differential adaptive responses on the activity and the membrane expression levels of these transporters. The neuronal GLYT2a isoform decreased in activity and surface expression and the mainly glial GLYT1b isoform slightly increased in function and surface density.

These changes may be involved in some of the modifications of glycinergic or glutamatergic neurotransmitter systems produced by ethanol intoxication.

Keywords: Ethanol, glycine, transport, stable expression, human embryonic kidney cells

Introduction

Glycine is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord and the brain stem of vertebrates, where it participates in a variety of motor and sensory functions. In addition, glycine could potentiate the action of glutamate, the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, on postsynaptic NMDA receptors. The re-uptake of glycine into presynaptic nerve terminals or the surrounding fine glial processes plays a major role in the maintenance of low synaptic levels of the transmitter (Iversen, 1971; Johnston & Iversen, 1971; Kanner & Schuldiner, 1987). Glycine transporters are members of the Na+- and Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family (Uhl & Hartig, 1992; Amara & Kuhar, 1993; Malandro & Kilberg, 1996), a group of integral glycoproteins (Núñez & Aragón, 1994; Olivares et al., 1995) which share a common structure with 12 transmembrane domains (Kanner & Kleinberger-Doron, 1994). Several neurotransmitter uptake systems, including those for glycine, present an unexpected molecular heterogeneity. Two glycine transporter genes (GLYT1 and GLYT2) have been cloned (Smith et al., 1992; Borowsky et al., 1993; Liu et al., 1993; Kim et al., 1994; Adams et al., 1995); GLYT1 presents three isoforms (GLYT1a, GLYT1b and GLYT1c) that differ in their amino terminal sequences and are generated both by alternative promoter usage and by alternative splicing (Smith et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1993; Adams et al., 1995; Borowsky & Hoffman, 1998). Recently, a second GLYT2 isoform (GLYT2b) has been isolated, cloned and characterized in our laboratory (Ponce et al., 1998). The GLYT1 variants are distinguishable from the GLYT2 ones by their brain distribution (Zafra et al., 1995a, 1995b), pharmacological profile, kinetic properties, Cl− affinity and electrical behaviour (López-Corcuera et al., 1998).

Ethanol is known to affect various neurotransmitter systems in the brain (Nevo & Hamon, 1995; Faingold et al., 1998). Chronic ethanol consumption leads to a new balance between many of these systems requiring continued ethanol administration to maintain it. Recent studies on the mechanisms of action of alcohols have been focused on a relatively small number of CNS targets, mainly ligand-gated ion channels. The depressant effect of ethanol may be due to an enhancement of inhibitory neurotransmission, which is mainly mediated by GABA and glycine. Thus, neurotransmitter receptors for these amino acids have been intensively studied as probable targets of ethanol action in the brain and the spinal cord (Franks & Lieb, 1994; Mascia et al., 1996a,1996b; Peoples et al., 1996; Diamond & Gordon, 1997; Mihic et al., 1997; Valenzuela & Harris, 1997; Wick et al., 1998). The function of the GABAA and the strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors is enhanced by a number of alcohols, suggesting their involvement in the behavioural actions of alcohol intoxication (Dildy-Mayfield et al., 1996; Mascia et al., 1996a,1996b; Valenzuela et al., 1998). In addition, changes in excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission, mediated by NMDA-receptors appear to play an important role in alcoholism (Tsai et al., 1995).

Alcohols in the homologous series of n-alkanols show increased CNS depressant potency with increasing chain length until a ‘cut-off' is reached after which, further increases in molecular size no longer increase alcohol potency (Lyon et al., 1981; Alifimoff et al., 1989). This effect has been attributed to direct interactions of alcohols with a hydrophobic pocket on a protein and not to a chaotropic effect of the alcohols on the membrane (Franks & Lieb, 1985).

In the present study, we have investigated the effects of ethanol on the glycine transporters GLYT1 and GLYT2 on the basis that changes in the activity of these proteins would modulate the glycine concentration in the synaptic cleft, and therefore its postsynaptic action on the receptors. GLYT1b and GLYT2a stably expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells show differential responses to acute and chronic treatments with ethanol.

Methods

Stable cell lines

Two ClaI/NotI restriction fragments containing the full length cDNAs of GLYT1b (rB20b clone) (Smith et al., 1992) or GLYT2a (Liu et al., 1993) were subcloned into the ClaI/NotI-digested pIRES1hyg bicistronic vector modified as previously described (López-Corcuera et al., 1998). The recombinant plasmids (10 μg) containing GLYT1b or GLYT2a under the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter were calcium-phosphate transfected (ProFection kit, Promega) into 50% confluent HEK 293 cells. Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated foetal bovine serum (DMEM+10% FBS), at 37°C, 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were diluted and switched to a medium containing 0.25 mg ml−1 hygromycin. Resistant colonies were isolated from transfected plates 4 weeks later during which medium was replaced every 4 days. Single cells were used to generate clonal lines. Selected clones for GLYT1b or GLYT2a stable cell lines expressed the highest levels of protein that immunoreacted with specific antibodies against GLYT1 or GLYT2, respectively (Zafra et al., 1995a,1995b). The clonal cell lines used in the experiments reported here showed saturable, high-affinity, and Na+ and Cl−-dependent glycine transport that was absent in the parental HEK 293 cells and that retained all the functional properties of every glycine transporter isoform (López-Corcuera et al., 1998).

Chronic ethanol treatment

Cells stably expressing GLYT2a and GLYT1b were grown on polylysine-covered 24-well plates in DMEM+10% FBS supplemented with different concentrations of ethanol (50–200 mM) for 3 days. Media were changed daily. Control cells were treated identically, except that no ethanol was added to the plates.

Transport assays

Subconfluent cells growing in polylysine-covered 24-well plates were washed at 37°C with 1 ml of KRP solution. The washing solution was removed, and cells were incubated for 10 min in KRP solution containing the n-alcohols. Afterwards, the solution was replaced by the uptake solution which contained an isotopic dilution of 3H-labelled glycine in KRP (final specific activity 59 μCi mmol−1), yielding a 10 μM final glycine concentration in the presence or absence of the n-alcohol tested at the concentration used in the incubation step. Transport was stopped with two 1 ml washes of ice-cold KRP, and cells dissolved in 0.25 ml of 0.2 M NaOH. Aliquots of each well were taken for scintillation counting and protein concentration determination. All the transport measurements were done in triplicate or quadruplicate and performed in parallel for HEK-GLYT1 or HEK-GLYT2 cells and for the parental HEK cells. Endogenous glycine uptake was subtracted from every data point in all the experiments with ethanol.

Electrophoresis and blotting

Crude membrane fractions of the different cultures were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) according to the method of Laemmli (1970) using a 4% stacking gel and 10% resolving gel. Samples were electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane in a semidry electroblotting system (Life Technologies, Inc.) of 1.2 mA.cm−2 for 2 h, using a transfer buffer comprising 192 mM glycine in 25 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5. After blocking the non-specific binding with 5% non-fat milk protein in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 4 h at 25°C, the blot was probed with a 1 : 750 and 1 : 500 dilution of a purified specific antibody against either GLYT1 or GLYT2, respectively (Zafra et al., 1995a,1995b) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Filters were washed and bound antibodies detected with a peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG. Bands were visualized with the ECL detection method (Amersham Corp.). Quantitative analysis of the band intensities was performed by densitometry (Molecular Dynamics Image Quant v. 3.0).

Cell surface labelling

Cell surface proteins of HEK-GLYT1 or HEK-GLYT2 stable cells were labelled with the cell membrane impermeable reagent sulpho-N-succinimidyl-2-biotinamido ethyl-1,3 dithiopropionate as previously described (Sargiacomo et al., 1989). In brief, cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 45 min in the presence of 1.5 mg ml−1 of the former reagent in ice-cold PBS. Then, cells were washed, and the excess of reagent was quenched with 100 mM lysine in PBS for 10 min. Cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer (mM): NaCl 150, HEPES-Tris 50, EDTA 5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.4, and biotinylated proteins were precipitaeted with streptavidin-agarose. Precipitated proteins were fractionated by SDS–PAGE and analysed by Western blot for immunoreactivity against anti-GLYT1 or anti-GLYT2 antibodies, as described above.

Protein concentration

Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (1976).

Materials

[2-3H]-Glycine (1.6 TBq.mmol−1) was supplied by DuPont-NEN. Ligase and restriction enzymes were from Boehringer Mannheim. Peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent were from Amersham Corp. (Bucks, U.K.). Sulpho-N-succinimidyl-2-biotinamidoethyl-1,3 dithiopropionate was from Pierce. n-Alkanols were purchased from Aldrich Chemicals Co (Milwaukee, WI, U.S.A.). The n-alkanols were diluted directly in (mM) Krebs Ringer Phosphate (KRP 140, NaCl 5, KCl 0.75, CaCl2 1.3, MgSO4 10, Na2HPO4 1, KH2PO4 10, glucose pH 7.4 immediately before use. All other reagents were obtained in the purest form available.

Results

Several neurotransmission pathways, including those mediated by glycine, localized in the spinal cord and the brain stem have been implicated in ethanol's intoxicating actions and in the mechanisms of general anaesthesia (Wong et al., 1997). In the present study we have examined the actions of several aliphatic n-alcohols on GLYT1 and GLYT2 glycine transporters as proteins implicated in glycine mediated neurotransmission, which represents, besides GABAergic pathways, the fastest inhibitory synaptic transmission in the spinal cord. HEK293 cell lines stably expressing either GLYT1b or GLYT2a were used in this study. Part of the biochemical and electrophysiological characterization of these cell lines has already been reported (López-Corcuera et al., 1998).

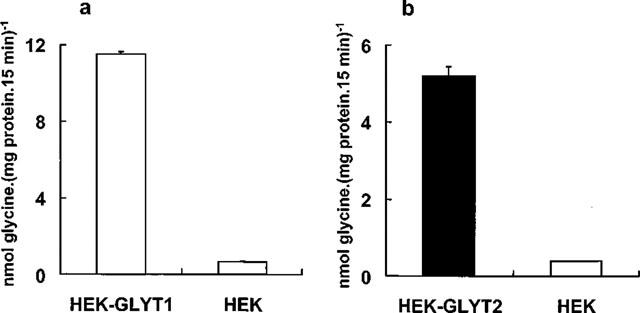

Figure 1 shows the glycine accumulation by the clonal cell lines stably expressing GLYT1b (Figure 1a) or GLYT2a (Figure 1b) compared with the substrate accumulation exhibited by the parental HEK293 cells. After a 15 min incubation in the presence of radiolabelled glycine (10 μM final concentration), clonal cell lines exhibited transport activities of approximately 16 fold (GLYT1b) or 7 fold (GLYT2a) over the background of the parental cells. Therefore, background glycine uptake represented, at 10 μM glycine, around 6% and 14% of the total glycine uptake by GLYT1b and GLYT2a stable cells, respectively. In the following experiments, only GLYT1b or GLYT2a-specific glycine uptake (calculated by subtracting the basal from the total glycine uptake of the stable cell lines) is shown.

Figure 1.

Glycine transport by GLYT1-HEK, GLYT2-HEK stable cell lines and HEK cells (background glycine uptake). Transport assays were performed as described in Methods. Each point represents the mean of three measurements and error bars represent s.e.mean.

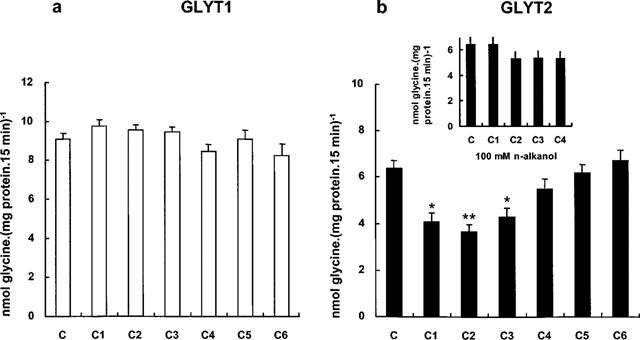

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of several aliphatic n-alcohols, from methanol to 1-hexanol, on the glycine transport activity by GLYT1 and GLYT2. For every alcohol, the concentration tested was the one which would result in a membrane alcohol concentration equivalent to that produced by 400 mM ethanol. To choose these concentrations, the alcohol's membrane/buffer partition coefficients were taken into account (McCreery & Hunt, 1978). As shown in Figure 2, methanol and 1-propanol produced a similar decrease in the activity of the GLYT2a isoform (by about 35%). At the same concentration, 1-butanol produced a smaller reduction on GLYT2a activity (approximately 15%), and alcohols longer than four carbon atoms (n=4) did not affect the glycine transport by GLYT2a. Similar concentrations of ethanol reduced GLYT2a activity to a greater extent than any other alcohol tested (about 45%). By contrast, no significant changes in GLYT1b activity were observed in the presence of any n-alcohol. Thus, n-alkanols exhibit a ‘cut-off' effect for GLYT2a inhibition that occurs between butanol and pentanol. This ‘cut-off' effect, defined as the chain length at which the potency of the n-alkanols no longer increases, is significantly lower than ‘cut-off' points reported for the effects of alcohols on lipids, which typically occur at more than 12 carbon atoms (Peoples et al., 1996). Moreover, the lack of effect of the n-alkanols tested on GLYT1b activity rules out a non-specific action on membrane lipids, as both glycine transporters are expressed and located in a membrane environment of the same cell type. However, no length ‘cut-off' was observed for GLYT2 when the same experiment was performed by using equal aqueous concentrations of methanol to butanol (100 mM) (Figure 2, inset). These experiments suggest a direct interaction of alcohols with a discrete site on the GLYT2a isoform to which alcohols may access from within the membrane or, alternatively, on a protein which specifically interacts with this glycine transporter.

Figure 2.

Effect of n-alcohols on GLYT1 (a) and GLYT2 (b) transport activities. Transport assays were performed in the absence of n-alcohol (C), or in the presence of comparative membrane concentrations of n-alcohols: 1 M methanol (C1), 400 mM ethanol (C2), 100 mM n-propanol (C3), 25 mM n-butanol (C4), 10 mM n-pentanol (C5) and 2.5 mM n-hexanol (C6). These concentrations were calculated after the membrane/buffer partition coefficients (McCreery & Hunt, 1978) which are: methanol, 0.036; ethanol, 0.096; n-propanol, 0.438; n-butanol, 1.52; n-pentanol, 5.02; n-hexanol, 21.4. Transport assays were performed as described in Methods. Background glycine uptake by HEK293 parental cells was subtracted from every data point. Means±s.e.mean of three determinations are represented. Statistically significant differences were determined by Student's t-test: *P<0.01, **P<0.001. Inset, effects of 100 mM C1, C2, C3, and C4 on GLYT2 transport activity.

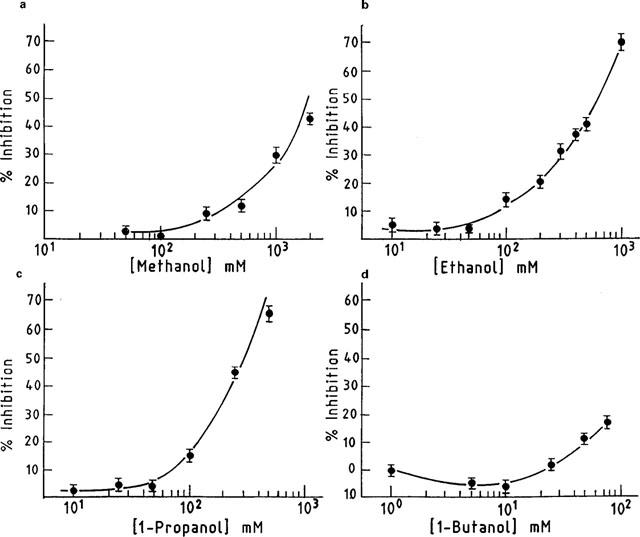

Figure 3 shows complete concentration-response curves for the effect of methanol, ethanol, 1-propanol and 1-butanol on the GLYT2 activity. Inhibition of glycine transport by methanol, ethanol or 1-propanol was concentration-dependent over a wide concentration range, and the concentrations that produced 50% inhibition (IC50) were 600 mM (Figure 3a), 350 mM (Figure 3b) and 200 mM (Figure 3c), respectively. By contrast, Figure 3d illustrates that 1-butanol did not significantly affect the GLYT2 activity even at concentrations that would result in a membrane alcohol concentration equivalent to that produced by more than 750 mM ethanol. When the same ethanol concentration range (10–1000 mM) was assayed on the GLYT1 activity, no inhibition was observed (data not shown). As the levels of GLYT1 stable expression were higher than those of GLYT2 (see Figure 1a), we assayed clones showing similar experssion levels of GLYT1 and GLYT2 proteins; even in these conditions, no change on the GLYT1 activity was observed in the presence of ethanol (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that the GLYT2 inhibition induced by ethanol appears to be a specific effect. In addition, results from Figures 2 and 3 suggest that the site of action of the n-alkanols might be an alcohol binding pocket in the protein which could accommodate alkyl chains of at least four methylene groups.

Figure 3.

Dose-response curves for inhibition of GLYT2 glycine transport activity by aliphatic n-alcohols. Transport rates were measured as described in Methods. Basal glycine uptake was subtracted from every value. The 100% specific control glycine transport rates were 4.3±0.2 (a), 4.9±0.25 (b), 4.65±0.3 (c) and 6.43±0.3 (d) nmol of glycine mg−1 of protein 15 min−1. Each point reflects triplicate measurements and s.e.mean are represented by bars.

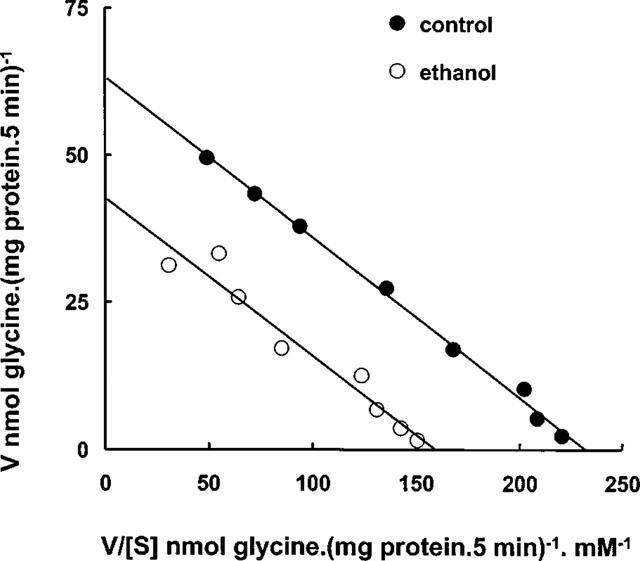

To determine whether the decrease in GLYT2 transport activity was due to a change in Km or Vmax of the transporter, we performed a kinetic analysis in the presence of clinically relevant concentrations of ethanol. Figure 4 shows an Eadie-Hofstee plot of the kinetic data from a representative experiment. This analysis yielded similar values for the apparent affinity constant (Km) in the absence (271±20 μM) and in the presence of 200 mM ethanol (246±19 μM). By contrast, in the presence of ethanol the Vmax decreased by 37% (39.7±2 nmol mg−1 of protein 5 min−1, versus 63.0± 4 nmol mg−1 of protein 5 min−1 of control).

Figure 4.

Eadie-Hofstee analysis of ethanol inhibition of glycine uptake by GLYT2. GLYT2-HEK cells were pre-incubated in the absence or in the presence of 200 mM ethanol for 20 min and [3H]glycine uptake was measured in the presence of 0.01–1 mM glycine for 5 min. Values were corrected for uptake by HEK293 parental cells. Linearization was obtained by least squares linear regression. The results are means of triplicate determinations. Mean Km and Vmax±s.e.mean are given under Results.

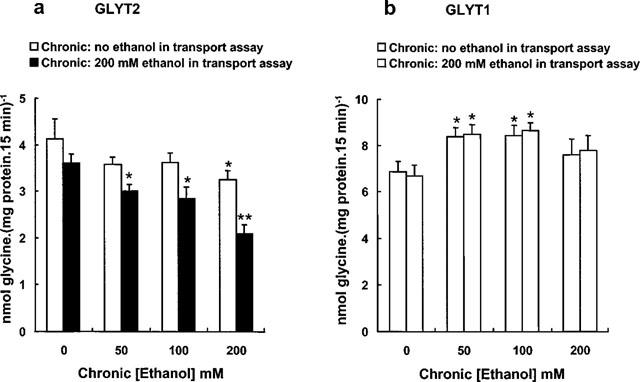

The subsequent studies were designed to test whether chronic ethanol exposure on GLYT2- and GLYT1-overexpressing cells produced adaptive changes on the transporter activity. Chronic ethanol exposure (at concentrations ranging from 50–200 mM) during 72 h reduced GLYT2 activity (by 13–22%) when measured in the absence of acutely administered ethanol (chronic effect, Figure 5a). After the chronic treatment, when transport was assayed in the presence of 200 mM ethanol, an additional decrease of GLYT2 activity was observed (17–32%). These results indicate that when GLYT2 is chronically exposed to different ethanol concentrations, the acute effect caused by 200 mM ethanol is not only maintained but is even more pronounced (Figure 5a). These data may suggest that the susceptibility of GLYT2 to ethanol is increased by the transporter's prolonged exposure to the alcohol. When HEK293 cells overexpressing GLYT1 transporter were treated chronically with ethanol, a different picture emerges when compared with GLYT2 (Figure 5b). Exposure to 100 and 200 mM ethanol for 72 h increased slightly GLYT1 activity and if the transport were assayed in the presence of 200 mM ethanol, a modest additional increase was detected.

Figure 5.

Effects of chronic treatment with ethanol on the glycine transport by GLYT2 (a) and GLYT1 (b) transporters. Cells were grown in the absence or in the presence of different concentrations of chronic ethanol for 3 days. Subsequently, glycine transport rates were measured in the absence or in the presence of 200 mM ethanol. For each condition, basal glycine uptake by the HEK293 parental cell line exposed to identical ethanol treatment, was subtracted to give the net rates shown. Results are mean±s.e.mean of six independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistically significant differences were determined by Student's t-test. *P<0.01, **P<0.001.

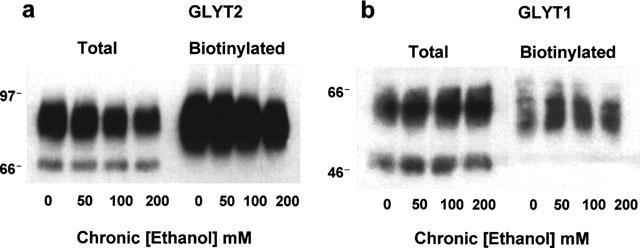

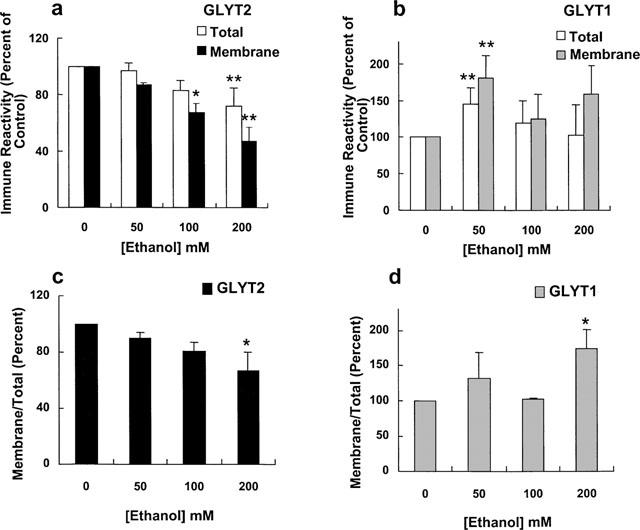

To determine whether the effects of ethanol on GLYT1 and GLYT2 transport activities were due to a change in surface transporter levels, we performed cell surface biotinylation experiments. Plasma membrane proteins were labelled with the membrane-impermeable reagent sulphosuccimido-NHS-biotin and the biotinylated proteins were precipitated with immobilized streptavidin followed by Western blot with previously characterized specific antibodies against the N-terminal domain of GLYT2 or the C-terminal portion of GLYT1 (Zafra et al., 1995a,1995b). The antibodies recognized two bands for each transporter: 90 and 67 kDa for GLYT2-HEK cells and 60 and 47 kDa for GLYT1-HEK. The upper bands are the totally processed transporters, present at the plasma membrane (Figure 6a,b, right blots), and the lower ones the partially glycosylated intracellular proteins (Figure 6a,b, left blots). GLYT2a-HEK cells exposed to 50–200 mM ethanol for 3 days showed a gradual dose-dependent decrease in the amount of total solubilized GLYT2 protein (Figure 6a, left blot and Figure 7a), and in the plasma membrane GLYT2 transporter (Figure 6a, right blot and Figure 7a), as quantitated after a densitometric analysis of the immunoblots. Furthermore, when the membrane GLYT2 protein was expressed as a percentage of the total solubilized protein (Figure 7c), a decrease in the cell surface GLYT2 protein was observed (67±13% of control at 200 mM, P<0.01, n=4 in a Student's t-test). This result suggests that ethanol impairs the optimal expression of GLYT2 transporters at the plasma membrane. Moreover, in the case of GLYT1, the chronic ethanol treatment produced an increase in the total and cell surface GLYT1 transporter (Figures 6b and 7b), and when the GLYT1b membrane protein was normalized for the total solubilized protein (Figure 7d), an increase in the GLYT1 plasma membrane expression was observed (174±27% of control at 200 mM ethanol, P<0.01, n=4 in a Student's t-test). From these data, it is apparent that the chronic ethanol treatment of GLYT2-HEK and GLYT1-HEK cells produces a differential regulation in the membrane expression of GLYT2a and GLYT1b proteins.

Figure 6.

Western blot of total and surface expression of the GLYT2 (a) and GLYT1 (b) transporters from control cells and cells treated chronically with ethanol. GLYT2-HEK and GLYT1-HEK cells were treated as described in Figure 5. Total cell protein (total) was solubilized, or cell surface proteins were biotinylated and isolated with streptavidin-agarose beds (biotinylated). Proteins were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted as described under Methods. Each lane in (a) (total) and (b) (total) represents approximately 9 and 7.5 μg of total cell protein respectively. Each lane in (a) (biotinylated) and (b) (biotinylated) represents an extract from approximately 90 and 60 μg of original cell protein, respectively. Molecular size in kDa are indicated on left side of a and b.

Figure 7.

Results from experiments similar to the one shown in Figure 6 were analysed by densitometry by integrating the total volume of each lane. Data are the average values from four experiments. The relative absorbance for the total and membrane protein are presented as mean±s.e.mean percentages of control (0). (c, d) Data from (a) (GLYT2) and (b) (GLYT1), respectively, were expressed as follows: (% of control membrane protein/% of control total protein)×100.

Discussion

In the present paper, we investigated the effects of n-alcohols on the function of recombinant GLYT1 and GLYT2 glycine transporters. We used the same cell type, HEK293 stably transfected either with GLYT1 or GLYT2, to compare the alcohol sensitivity of every isoform in an identical expression system.

In this study, we found that GLYT2 activity was inhibited with increasing potency by methanol, ethanol and n-propanol. However, n-alcohols with four or more carbon atoms did not impair GLYT2 activity even at doses that would produce membrane alcohol concentrations equivalent to that produced by 400 mM ethanol. By contrast, n-alcohols tested in this study did not have a significant effect on GLYT1 transport activity. Because both glycine transporters are expressed in the same cellular background, our results indicate that short chain alcohols selectively inhibit the function of GLYT2 either directly or through a protein specifically interacting with this isoform. The different sensitivity of GLYT1 and GLYT2 to these alcohols and the alcohol ‘cut-off' effect observed on GLYT2, argue against membrane lipids as sites of alcohol action. It is well known that the potencies of n-alcohols in producing central nervous system depression increase with the carbon chain length but only up to a certain size, the ‘cut-off', after which, alcohols with longer carbon chains decline in potency and efficacy (Lyon et al., 1981; Franks & Lieb, 1985; Alifimoff et al., 1989). The proposed mechanism for the ‘cut-off' phenomenon is that there exists a discrete alcohol binding site located on the protein of finite size that will accommodate only alcohols below a certain limit of molecular volume (Franks & Lieb, 1985). When the size of the alcohols exceeds the dimensions of their binding site on the protein, the alcohols are unable to bind, and their activity thus disappears at the ‘cut-off' point. According to this model, the binding pocket on GLYT2 (or on a GLYT2-specific partner) cannot completely fit alcohols larger than butanol when assuming that the n-alkanols act from within the membrane. Since this effect was not observed when equal aqueous concentrations of every n-alkanol (100 mM) were used, the site of action of the n-alkanols on GLYT2 might be accessible from the membrane or even intracellularly located. This ‘cut-off' (n=4) is well below those demonstrated for membrane lipid effects, which typically occur at more than 12 carbon atoms (Peoples et al., 1996).

Studies on the mechanisms of action of alcohols have been focused on a relatively small number of CNS targets, mainly ligand-gated ion channels. All these membrane proteins show ‘cut-off' behaviour, which varies for each protein. Thus, the ‘cut-off' (for straight-chain aliphatic alcohols) for GABAA and glycine receptors is at n=10–12 (Dildy-Mayfield et al., 1996; Mascia et al., 1996a,1996b; Wick et al., 1998), and for NMDA, kainate, and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA) receptors is at n=7 or 8 (Peoples & Weight, 1995; Dildy-Mayfield et al., 1996). Smaller ‘cut-off' is seen in the serotonin (5-HT3) receptor which falls at n=5 (Fan & Weight, 1994), and the reported ‘cut-off' for the ATP-gated ion channel is at n=3 (Li et al., 1994). These data suggest that the sizes of the alcohol binding pockets substantially vary, probably influenced by the details of the protein structures.

Non-competitive type of inhibition mediated by ethanol, as observed for GLYT2 transporter has been described for other proteins involved in neurotransmission, such as the acetylcholine (nAChα,7) receptor (Yu et al., 1996) and NMDA receptors (Wright et al., 1996). This non-competitive antagonism indicates an allosteric modulation by ethanol of GLYT2 activity.

Depression of CNS function by ethanol is a complex phenomenon (Deitrich et al., 1989; Samson & Harris, 1992) which may involve several neurotransmitter systems (Nevo & Hamon, 1995). Ligand-gated ion channels such as the NMDA and non-NMDA subtypes of glutamate receptors (Lovinger et al., 1989; Lovinger, 1993; Dildy-Mayfield & Harris, 1995) and the GABA receptors (Mihic & Harris, 1996) are sensitive to clinically relevant concentrations of ethanol, being involved in acute and chronic effects. More recently, evidence has been obtained to implicate the glycine receptor (Gly-R) in some of the ethanol actions. Behavioural studies have shown that glycine, like GABA, enhances the central depressant effects of ethanol. Intracerebroventricular administration of glycine increases ethanol-induced loss of the righting reflex in the mouse (Williams et al., 1995), and this effect is blocked by the glycine antagonist, strychnine.

Studies performed using different techniques and preparations have shown that ethanol enhances Gly-R function by increasing glycine-mediated Cl−flux (Celentano et al., 1988; Engblom & Akerman, 1991; Aguayo & Pancetti, 1994; Mascia et al., 1996a,1996b). It has recently been demonstrated that single amino acid replacements at Ser-267 within transmembrane domain two of the Gly-Rα1 subunit could completely remove ethanol enhancement of Gly-R function (Mihic et al., 1997; Ye et al., 1998). Activation of glycinergic transmission by ethanol could be mediated through two mechanisms: a stimulatory effect on the Gly-R and also an inhibitory effect on the glycine transporters. If the uptake is decreased, glycine concentration in the synaptic cleft increases and this results in a subsequent activation of glycine receptors. Our results suggest that GLYT2 is a target for the acute effects of ethanol. The location of GLYT2 is, in general, in good agreement with the distribution of the glycine receptor (Jursky & Nelson, 1995; Luque et al., 1995) and with that of glycine immunoreactivity (Poyatos et al., 1997); thus, GLYT2 seems to be associated exclusively with inhibitory glycinergic neurotransmission. A dual effect of ethanol, either increasing GlyR function and decreasing GLYT2 activity, may result in a potentiation of the glycinergic neurotransmission and could explain in part the depressant effects induced by ethanol in the CNS.

Other neurotransmitter transporters in neural cells have also been described as targets of ethanol, such as a specific facilitative nucleoside transporter. The inhibition of this transporter leads to an increase in extracellular adenosine, which causes activation of adenosine A2 receptors and consequently changes in receptor-mediated signal transduction (Nagy et al., 1990; Coe et al., 1996).

Another interesting aspect of this study is the inhibition of GLYT2 activity observed following chronic ethanol treatment which appears to correlate with a significant decrease of surface GLYT2 density. These results, suggest that GLYT2 appears to be subjected to changes that develop sensitization during chronic ethanol abuse. These changes could counteract some of the proposed mechanisms underlying the development of tolerance to chronic ethanol consumption, such as the reduced GABAergic and increased glutamatergic neurotransmission (Nevo & Hamon, 1995; Faingold et al., 1998). Moreover, it has been described that human tolerant alcoholics may appear sober or only mildly intoxicated with ethanol blood levels around 150 mM (Gerstin et al., 1998). Therefore, the concentrations of ethanol (50–200 mM) producing the changes in GLYT2 described above are in the pharmacologically and clinically relevant concentration range (Mihic & Harris, 1996; Mascia et al., 1996b). In conclusion, the possibility that GLYT2 could be involved in pathological situations induced by ethanol abuse should be strongly considered.

A different modulation of the expression of GLYT1 was produced by chronic ethanol treatment. A slight increase in the activity of the transporter runs parallel with a moderately higher level of surface expression GLYT1 when compared with the untreated GLYT1-cells. These changes may be involved in the mechanism of tolerance to ethanol. It has been shown that chronic ethanol treatment enhances the NMDA-induced excitotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons (Chandler et al., 1993). Considering that the mainly glial location of GLYT1 has been correlated with that of several NMDA receptor subunits (Smith et al., 1992) and that its function has been shown to efficiently regulate local glycine levels (Supplisson & Bergman, 1997; Bergeron et al., 1998), GLYT1 function could modulate NMDA receptor activity. The adaptive changes on GLYT1 produced by ethanol might contribute to maintain a more normal degree of receptor-activated signalling even in the continued presence of ethanol.

In summary, these results demonstrate for the first time that acute and chronic effects of ethanol impair the function of GLYT2 and the surface density of this neuronal glycine transporter. Moreover, chronic ethanol exerts an increase in the activity and in the membrane levels of the mainly glial isoform GLYT1. These changes, together with those described for other neurotransmitter systems in the brain, may support some of the modifications produced in the glycine-mediated neurotransmission as a consequence of ethanol intoxication. Further studies on brain-derived preparations will reveal the mechanisms underlying these changes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (PM 95-0026), and European Union TMR Program (FMRX-CT98-0228) and an institutional grant from the Fundación Ramón Areces. The authors want to thank Drs K.E. Smith and R.L. Weinshank from Synaptic Pharmaceutical Corp. for providing the rB20 clone, Dr A. Martinez-Serrano for generous gift of the pIRES1hyg vector, and E.L. Salero for his valuable assistance in the processing of Figure 7.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- ECL

enhanced chemiluminescence

- FBS

foetal bovine serum

- Gly-R

glycine receptor

- GLYT1 and GLYT2

glycine transporters 1 and 2

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- 5-HT

serotonin

- KRP

Krebs Ringer phosphate

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

References

- ADAMS R.H., SATO K., SHIMADA S., TOHYAMA M., PÜSCHEL A.W., BETZ H. Gene structure and glial expression of the glycine transporter GLYT1 in embryonic and adult rodents. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:2524–2532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02524.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGUAYO L.G., PANCETTI F.C. Ethanol modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acidA- and glycine-activated Cl− current in cultured mouse neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;270:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALIFIMOFF J.K., FIRESTONE L.L., MILLER K.W. Anaesthetic potencies of primary alkanols: implications for the molecular dimension of the anaesthetic target sites provides a molecular basis for cut-off effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;96:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMARA S.G., KUHAR J. Neurotransmitter transporters: recent progress. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1993;16:73–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGERON R., MEYER T.M., COYLE J.T., GREENE R.W. Modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function by glycine transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:15730–15734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOROWSKY B., HOFFMAN B.J. Analysis of a gene encoding two glycine transporter variants reveals alternative promoter usage and a novel gene structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:29077–29085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOROWSKY B., MEZEY E., HOFFMAN B.J. Two glycine transporters variants with distinct localization in the CNS and peripheral tissues are encoded by a common gene. Neuron. 1993;10:851–863. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADFORD M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CELENTANO J.J., GIBBS T.T., FARB D.H. Ethanol potentiates GABA- and glycine-induced chloride currents in chick spinal cord neurons. Brain Res. 1988;455:377–380. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANDLER L.J., NEWSOM H., SUMNERS C., CREWS F. Chronic ethanol exposure potentiates NMDA excitotoxicity in cerebral cortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:1578–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COE I.R., YAO L., DIAMOND I., GORDON A.S. The role of protein kinase C in cellular tolerance to ethanol. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:29468–29472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEITRICH R.A., DUNWIDDIE T.V., HARRIS R.A., ERWIN V.G. Mechanism of action of ethanol: initial central nervous system actions. Pharmacol. Rev. 1989;41:489–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIAMOND I., GORDON A.S. Cellular and molecular neuroscience of alcoholism. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:1–20. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DILDY-MAYFIELD J.E., MIHIC S.J., LIU Y., DEITRICH R.A., HARRIS R.A. Actions of long chain alcohols on GABAA and glutamate receptors: relation to in vivo effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DILDY-MAYFIELD J.E., HARRIS R.A. Ethanol inhibits kainate responses of glutamate receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes: role of calcium and protein kinase C. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:3162–3171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-03162.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGBLOM A.C., AKERMAN K.E.O. Effects of ethanol on gamma-aminobutyric acid- and glycine receptor-coupled Cl− fluxes in rat brain synaptoneurosomes. J. Neurochem. 1991;57:384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb03764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAINGOLD C.L., N'GOUNEMO P., RIAZ A. Ethanol and neurotransmitter interactions from molecular to integrative effects. Proc. Neurobiol. 1998;55:509–535. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAN P., WEIGHT F.F. Alcohols exhibit a cut-off effect for the potentiation of 5-HT3 receptor-activated current. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1994;20:1127. [Google Scholar]

- FRANKS N.P., LIEB W.R. Mapping of general anaesthetic target sites provides a molecular basis for cut-off effects. Nature. 1985;316:349–351. doi: 10.1038/316349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANKS N.P., LIEB W.R. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of anaesthesia. Nature. 1984;367:607–614. doi: 10.1038/367607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERSTIN E.H., JR, MCMAHON T., DADGAR J., MESSING R.O. Protein Kinase CΔ mediates ethanol induced up-regulation of L-type calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16409–16414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IVERSEN L.L. Role of transmitter uptake mechanisms in synaptic transmission. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1971;41:571–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTON G.A.R., IVERSEN L.L. Glycine uptake in rat CNS slices and homogenates; evidence for different uptake systems in spinal cord and cerebral cortex. J. Neurochem. 1971;18:1951–1961. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1971.tb09601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JURSKY F., NELSON N. Localization of glycine neurotransmitter transporter (GLYT2) reveals correlations with the distribution of glycine receptor. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:1026–1033. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64031026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANNER B.I., KLEINBERGER-DORON N. Structure and function of sodium-coupled neurotransmitter transporters. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 1994;4:174–184. doi: 10.1159/000173821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANNER B.I., SHULDINER S. Mechanism of transport and storage of neurotransmitters. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1987;22:1–38. doi: 10.3109/10409238709082546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM K.M., KINGSMORE S.F., HAN H., YANG-FENG T.L., GODINOT N., SELDIN M.F., CARON M.G., GIROS B. Cloning of the human glycine transporter type 1: Molecular and pharmacological characterization of novel isoform variants and chromosomal localization of the gene in the human and mouse genomes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:608–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAEMMLI U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI C., PEOPLES R.W., WEIGHT F.F. Alcohol action on a neuronal membrane recepotr: Evidence for a direct interaction with the receptor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:8200–8204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU Q.R., LÓPEZ-CORCUERA B., MANDIYAN S., NELSON H., NELSON N. Cloning and expression of a spinal cord- and brain-specific glycine transporter with novel structure features. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:22802–22808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LÓPEZ-CORCUERA B., MARTÍNEZ-MAZA R., NÚÑEZ E., ROUX M., SUPPLISSON S., ARAGÓN C. Differential properties of two stably expressed brain-specific glycine transporters. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:2211–2219. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOVINGER D.M. High ethanol sensitivity of recombinant AMP-type glutamate expressed in mammalian cells. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;159:83–97. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90804-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOVINGER D.M., WITHE G., WEIGHT F.F. Ethanol inhibits NMDA-activated ion current in hippocampal neurons. Science. 1989;243:1721–1724. doi: 10.1126/science.2467382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUQUE J.M., NELSON N., RICHARD J.G. Cellular expression of glycine transporter 2 messenger RNA exclusively in rat hindbrain and spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1995;64:525–535. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00404-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYON R.C., MCCOMB J.A., SCHREURS J., GOLDSTEIN D.B. A relationship between alcohol intoxication and the disordering of brain membranes by a series of short-chain alcohols. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1981;218:669–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALANDRO M.S., KILBERG M.S. Molecular biology of mammalian amino acid transporters. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:305–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASCIA M.P., MACHU T.K., HARRIS R.A. Enhancement of homomeric glycine receptor function by long-chain alcohols and anaesthetics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996a;119:1331–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASCIA M.P., MIHIC S.J., VALENZUELA C.F., SCHOFIELD P.R., HARRIS R.A. A single amino acid determines differences in ethanol actions on strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996b;50:402–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCREERY M.J., HUNT W.A. Physico-chemical correlates of alcohol intoxication. Neuropharmacol. 1978;17:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(78)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIHIC S.J., HARRIS R.A. Pharmacological effects of ethanol on the nervous system 1996CRC Press Boca Raton, Florida; 51–72.de Dietrich, R.A. & Erwin, V.G. pp [Google Scholar]

- MIHIC S.J., YE Q., WICK M.J., KOLTCHINE V.V., KRASOWSKI M.D., FINN S.E., MASCIA M.P., VALENZUELA C.F., HANSON K.K., GREENBLATT E.P., HARRIS R.A., HARRISON N.L. sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGY L.E., DIAMOND I., CASSO D.J., FRANKLIN C., GORDON A.S. Ethanol increases extracellular adenosine by inhibiting adenosine uptake via the adenosine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1946–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEVO I., HAMON M. Neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory mechanisms involved in alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Neurochem. Int. 1995;26:305–336. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)00139-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NÚÑEZ E., ARAGÓN C. Structural analysis and functional role of the carbohydrate component of glycine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:16920–16924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLIVARES L., ARAGÓN C., GIMÉNEZ C., ZAFRA F. The role of N-glycosylation in the activity and targeting of GLYT1 glycine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:9437–9442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEOPLES R.W., WEIGHT F.F. Cut-off in potency implicates alcohol inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in alcohol intoxication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:2825–2829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEOPLES R.W., LI C., WEIGHT C.F. Lipid vs protein theories of alcohol action in the nervous system. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;36:185–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.001153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PONCE J., POYATOS I., ARAGÓN C., GIMÉNEZ C., ZAFRA F. Characterization of the 5′ region of the rat brain glycine transporter GLT2 gene: identification of a novel isoform. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;242:25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYATOS I., PONCE J., ARAGÓN C., GIMÉNEZ C., ZAFRA F. The glycine transporter GLYT2 is a reliable marker for glycine-immunoreactive neurons. Mol. Brain Res. 1997;49:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMSON H.H., HARRIS R.A. Neurobiology of alcohol abuse. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13:206–211. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90065-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGIACOMO M., LISANTI M.P., GRAEVE L., LE BIVIC A., RODRIGUEZ-BOULAN E. Integral and peripheral protein composition of the apical and basolateral membrane domains in MDCK cells. J. Membr. Biol. 1989;107:277–286. doi: 10.1007/BF01871942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH K.E., BORDEN L.A., HARTIG P.R., BRANCHEK T., WEINSHANK R.L. Cloning and expression of a glycine transporter reveal co-localization with NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:927–935. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90207-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUPPLISSON S., BERGMAN C. Control of NMDA receptor activation by a glycine transporter co-expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:4580–4590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04580.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSAI G., GASTFRIEND D.R., COYLE J.T. The glutamergic basis of human alcoholism. Am. J. Psychiat. 1995;152:332–340. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UHL G.R., HARTIG P.R. Transport explosion: update on uptake. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13:421–425. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90133-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALENZUELA C.F., HARRIS R.A. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore; 1997. pp. 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- VALENZUELA C.F., CARDOSO R.A., WICK M.J., WEINER J.L., DUNWIDDIE T.V., HARRIS R.A. Effects of ethanol on recombinant glycine receptors expressed in mammalian cell lines. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22:1132–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WICK M.J., MIHIC S.J., UENO S., MASCIA M.P., TRUDELL J.R., BROZOWSKI S.J., YE Q., HARRISON N.L., HARRIS R.A. Mutations of γ-aminobutyric acid and glycine receptors change alcohol cut-off: evidence for an alcohol receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:6504–6509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS K.L., FLERKO A.P., BARBIERI E.J., DIGREGORIO G.J. Glycine enhances the central depressant properties of ethanol in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1995;50:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00288-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WONG S.M.E., FONG E., TAUCK D.L., KENDIG T.J. Ethanol as a general anesthetic: actions in the spinal cord. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;329:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT J.M., PEOPLES R.W., WEIGHT F.F. Single-channel and whole-cell analysis of ethanol inhibition of NMDA-activated currents in cultured mouse cortical and hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1996;738:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YE Q., KOLTCHINE V.V., MIHIC S.J., MASCIA M.P., WICK M.J., FINN S.E., HARRISON N.L., HARRIS R.A. Enhancement of glycine receptor function by ethanol is inversely correlated with molecular volume at position α267. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3314–3319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU D., ZHANG L., EISELÉ J.-L., BERTRAND D., CHANGEUX J.-P., WEIGHT F.F. Ethanol inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine type α7 receptors involves the amino-terminal domain of the receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:1010–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAFRA F., ARAGÓN C., OLIVARES L., DANBOLT N.C., GIMÉNEZ C., STORM-MATHISEN J. Glycine transporters are differently expressed among CNS cells. J. Neurosci. 1995a;15:3952–3969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03952.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAFRA F., GOMEZA J., OLIVARES L., ARAGÓN C., GIMÉNEZ C. Regional distribution and developmental variation of the glycine transporters GLYT1 and GLYT2 in the rat CNS. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995b;7:1342–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]