Abstract

The possible mechanisms underlying the vasodilatation induced by olprinone, a phosphodiesterase type III inhibitor, were investigated in smooth muscle of the rabbit coronary artery. Isometric force and membrane potential were measured simultaneously using endothelium-denuded smooth muscle strips.

Acetylcholine (ACh, 3 μM) produced a contraction with a membrane depolarization (15.2±1.1 mV). In a solution containing 5.9 mM K+, olprinone (100 μM) hyperpolarized the resting membrane and (i) caused the absolute membrane potential level reached with ACh to be more negative (but did not reduce the delta membrane potential seen with ACh, 15.2±1.8 mV) and (ii) attenuated the ACh-induced contraction. In a solution containing 30 mM K+, these effects were not seen with olprinone.

Glibenclamide (10 μM) blocked the olprinone-induced membrane hyperpolarization. 4-AP (0.1 mM) significantly attenuated the olprinone-induced resting membrane hyperpolarization but TEA (1 mM) had no such effect.

Glibenclamide (10 μM), TEA (1 mM) and 4-AP (0.1 mM), given separately, all failed to modify the inhibitory actions of olprinone on (i) the absolute membrane potential level seen with ACh and (ii) the ACh-induced contraction.

It is suggested that olprinone inhibits the ACh-induced contraction through an effect on the absolute level of membrane potential achieved with ACh in smooth muscle of the rabbit coronary artery. It is also suggested that glibenclamide-sensitive, ATP-sensitive K+ channels do not play an important role in the olprinone-induced inhibition of the ACh-induced contraction.

Keywords: Olprinone, phosphodiesterase, coronary artery, smooth muscle, acetylcholine, membrane hyperpolarization, ATP-sensitive K+ channel

Introduction

Some inhibitors of phosphodiesterase type III (cyclic GMP-inhibited phosphodiesterase, PDE III) are currently used for the treatment of acute heart failure. One of these is olprinone hydrochloride (1, 2-dihydro-6-methyl-2-oxo-5-(imidazo[1, 2-a]pyridin-6-yl)-3-pyridine carbonitrile hydrochloride monohydrate). This agent has been found to be a selective inhibitor of PDE III, the enzyme which, by inhibiting the breakdown of adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cylic AMP), increases its cellular concentration (Ogawa et al., 1989; Ohoka et al., 1990; Itoh et al., 1993). While the therapeutic effect of PDE III inhibitors in heart failure is thought mainly to be achieved via their cardiotonic action, these drugs are known to possess vasodilator activity in resistance arteries via their effects on cyclic AMP (Tajimi et al., 1991; Takaoka et al., 1993).

It was found some years ago that olprinone hydrochloride increases blood flow in the canine coronary circulation (Ohhara et al., 1989) with a concomitant increase in myocardial oxygen supply. From the clinical point of view, this action could be quite important for a cardiotonic drug since cardiac ischaemia is a major cause of acute heart failure. The following mechanisms have been proposed to try to explain the vasorelaxation induced by cyclic AMP-increasing agents: (1) a membrane hyperpolarizing or repolarizing action (Rembold & Chen, 1998), (2) an acceleration of Ca2+-uptake into the Ca2+-storage sites and/or an inhibition of the release of Ca2+ from the stores (Ito et al., 1993; Chen & Rembold, 1996) and (3) a reduction in myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity in smooth muscle (Ito et al., 1993; Van Riper et al., 1995). However, the precise mechanisms underlying the vasodilatation induced by olprinone have not yet been clarified using the smooth muscle of the coronary artery.

In the present study, we set out to clarify the mechanisms underlying olprinone-induced vasorelaxation using smooth muscle from a rabbit coronary resistance artery. To do this, we developed a technique for measuring the membrane potential and isometric force simultaneously in endothelium-denuded smooth muscle strips prepared from the peripheral part of the rabbit coronary artery. Using this technique, the changes induced by olprinone in the electrical and mechanical effects of ACh were measured simultaneously. The effects on the olprinone-induced responses produced by various types of K+-channel inhibitors were also studied.

Methods

Tissue preparation

Male Japan White albino rabbits (supplied by Kitayama Labes, Nagano, Japan), weighing 1.9–2.3 kg, were anaesthetized with pentobarbitone sodium (40 mg kg−1, i.v.) and then exsanguinated. The protocols used conformed with guidelines on the conduct of animal experiments issued by Nagoya City University Medical School and by the Japanese government (Law no. 105; Notification no. 6) and were approved by The Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments in Nagoya City University Medical School. The heart was rapidly excised and placed in Krebs solution. The distal segment of the left circumflex coronary artery (diameter approximately 0.3–0.4 mm) was dissected free under a binocular microscope and connective tissues were carefully removed. After the artery had been cut along its long axis with small scissors, the endothelium of the strip (0.9–1.2 mm long, 0.1–0.2 mm wide) was carefully removed by gentle rubbing of the internal surface with a small piece of razor blade. Satisfactory ablation of the endothelium was pharmacologically verified by the absence of a membrane hyperpolarization to 3 μM ACh. The strip was mounted horizontally in a chamber of 0.3 ml volume placed on the stage of an invert-microscope (Diaphoto TMD, Nikon, Japan) and it was superfused with oxygenized Krebs solution at a rate of 4 ml min−1. A length of strip approximately one-half of the total length was pinned down to the bottom of the chamber to enable measurement of membrane potential. The free end was tied with a fine silk thread to a strain gauge transducer to enable isometric force to be measured simultaneously in the remaining half of the strip. The resting tension was adjusted to obtain a maximum contraction to 80 mM K+.

Membrane potential and force measurement

The membrane potential was measured using conventional microelectrode technique. Glass microelectrodes made from borosilicate glass tubing (o.d. 1.2 mm with a glass filament inside; Hilgenberg, Germany) were filled with 1 M KCl. The resistance of the electrodes was 120–180 MΩ. The electrode was inserted into smooth muscle cells from the adventitial side using a micromanipulator (model MHW-3; Narishige International, Tokyo, Japan). The criteria for the acceptable impalement of a smooth muscle cell were that membrane potential was stable for at least 5 min prior to every experimental procedure and showed sharp changes on penetration and withdrawal. Successful recordings could usually be obtained for at least 20 min and for up to 3 h. Membrane potentials recorded using an Axoclamp-2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster, CA, U.S.A.) were displayed on a cathode-ray oscilloscope (model VC-6020; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Data relating to membrane potential and isometric force were simultaneously stored at an acquisition rate of 200 Hz using an AxoScope 1.1.1/Digidata 1200 data acquisition system (Axon Instruments, Foster, CA, U.S.A.) on an IBM/AT compatible PC. When oscillations in tension or membrane potential occurred in the presence of ACh, the level was taken to be at the mid-point of the amplitude of the oscillations.

When ACh (0.01–10 μM) was intermittently applied for 5 min at 20-min intervals in an ascending order in the same preparation, maximum responses were obtained with 3 μM ACh. Consequently, the effects of olprinone were studied on the response induced by 3 μM ACh. Changes in membrane potential and smooth muscle contraction induced by ACh were obtained in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of olprinone, the tests being carried out at 20-min intervals. To this end, the ACh-induced response was first recorded, followed by a 20-min intermission. Next, olprinone was applied for 15 min before and during the second application of ACh. To study whether or not particular K+ channels are involved in the inhibitory action of olprinone on the ACh-induced membrane depolarization and contraction, the effects of several types of K+ channel blocker were examined. For this set of experiments, the first ACh (3 μM) response was obtained using the protocol described above. Then, 100 μM olprinone was applied for 15 min and a given K+-channel blocker was subsequently applied for 10 min in the continued presence of olprinone. Finally, 3 μM ACh was again applied (the second application) in the presence of the K+-channel blocker together with olprinone. All of these steps were performed in one and the same strip but each strip was exposed to only one K+ channel blocker. Thus, each strip acted as its own control for the effect of a single K+ channel blocker. The concentrations of the K+ channel blockers used were chosen so as to retain their selectivity.

The effects of olprinone on the ACh (3 μM)-induced membrane depolarization and contraction were also studied in a solution containing high K+ (30 mM), in which the high K+ solution was applied for 5 min before and during application of 3 μM ACh in the absence or presence of 100 μM olprinone.

The roles of Na+ channels, Cl− channels and non-selective cation channels in the mediation of the ACh-induced membrane depolarization and contraction were examined using solutions containing low Na+ (15.5 mM), 5-nitro-2-(3-phenyl-propylamino)benzoic acid (NPPB, 10 μM) or Co2+ (1 mM), respectively. For this set of experiments, the first ACh (3 μM)-response was recorded using the protocol described above. Then, a low Na+, NPPB or Co2+ solution was applied for 10 min and, in the presence of this solution, ACh was applied again.

Solutions

The composition of the Krebs solution was as follows (mM): NaCl, 122; KCl, 4.7; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.6; NaHCO3, 15.5; KH2PO4, 1.2; glucose, 11.5. The solutions were bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and their pH was maintained at 7.3–7.4. High K+ solution was made by isotonic replacement of NaCl with KCl. To prepare a solution containing low Na+ (15.5 mM), NaCl was replaced iso-osmotically with Tris-HCl (pH 7.4).

Chemicals

The drugs used were glibenclamide and isoprenaline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) (Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan), NPPB (Research Biochemicals International, Natick, MA, U.S.A.) and acetylcholine hydrochloride (Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Olprinone hydrochloride was kindly provided by Eisai Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Glibenclamide was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO; Dojin, Kumamoto, Japan). The final concentration of DMSO when diluted in Krebs solution was 0.06% at maximum. This concentration of DMSO had no effect on the ACh-induced electrical and mechanical responses. The other drugs were dissolved in ultra-pure Milli-Q water (Milli-Q SP/Milli RX system; Japan Millipore Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Data analysis

All values are expressed as mean±s.e.mean, with n denoting the number of strips. Statistical significance was determined using Student's paired and unpaired t-tests. Regression analysis was performed by the least-squares method, slopes being compared by calculating residual variances and use of a t-test. Differences were considered to be significant at P<0.05. Relative force represents the force recorded relative to the 3 μM ACh-induced contraction in the same strip.

Results

Effect of olprinone on ACh-induced electrical and mechanical responses

The resting membrane potential was −50.3±0.7 mV (n=38) in smooth muscle cells of endothelium-denuded rabbit coronary arteries. ACh (3 μM) depolarized the membrane by 15.2±1.1 mV (n=9) and produced a contraction (Figures 1A and 2).

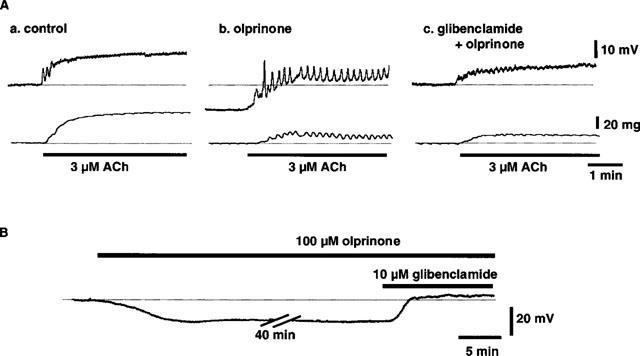

Figure 1.

Effects of olprinone (100 μM) on ACh (3 μM)-induced membrane depolarization and contraction in the presence and absence of glibenclamide (10 μM) in endothelium-denuded rabbit coronary artery. (A) shows actual tracings of simultaneously recorded membrane potential (upper traces) and isometric force (lower traces) in control (A,a), in the presence of olprinone (A,b) and in the presence of both olprinone and glibenclamide (A,c). Recordings were all from the same cell. (B) Effect of glibenclamide (10 μM) on membrane hyperpolarization induced by olprinone (100 μM).

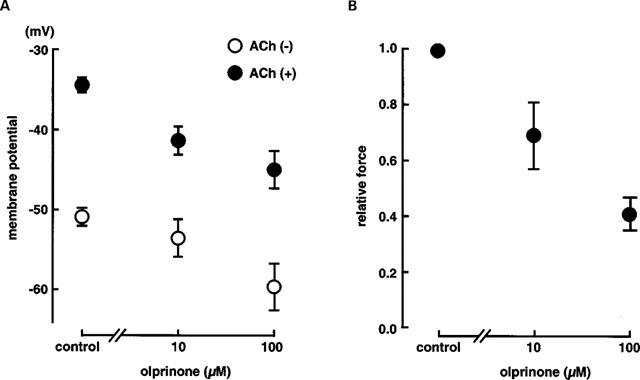

Figure 2.

(A) Effects of olprinone (10 and 100 μM) on membrane potential in the presence of 3 μM ACh and in the quiescent state in endothelium-denuded rabbit coronary arteries. Each data point shows mean from four preparations with s.e.mean shown by vertical lines. (B) Effects of olprinone (10 and 100 μM) on ACh (3 μM)-induced contraction in endothelium-denuded rabbit coronary arteries. Each data point shows mean from four preparations with s.e.mean shown by vertical lines.

Olprinone (100 μM) hyperpolarized the resting membrane (by 8.3±1.5 mV, n=4, P<0.01) with no change in the resting tension. In its presence, the absolute membrane potential level achieved with 3 μM ACh was more negative than in the absence of olprinone (‘relative hyperpolarization') and the concomitant contraction was attenuated (Figures 1 and 2). However, the ACh-induced delta membrane potential (the change in membrane potential produced by an application of ACh) was not significantly altered by olprinone (15.2±1.1 mV in control, 15.2±1.8 mV in the presence of 100 μM olprinone, n=4, P>0.1). In the presence of 100 μM olprinone, 3 μM ACh produced an oscillatory membrane response with a time-matched oscillatory mechanical response (Figure 1A,b). The inhibitory actions of olprinone on the ACh-induced electrical and mechanical responses were concentration-dependent, at 10 and 100 μM (Figure 2).

Isoprenaline (0.1 μM), a β-adrenoceptor stimulant, also hyperpolarized the resting membrane (to −62.8±1.6 mV, P<0.01). In its presence, the absolute membrane potential level achieved in the presence of 3 μM ACh was more negative than in its absence (−45.8±5.6 mV, P<0.01) and the concomitant contraction was attenuated (0.52±0.06 times control, P<0.05) (n=6).

Effect of high K+ on the action of olprinone

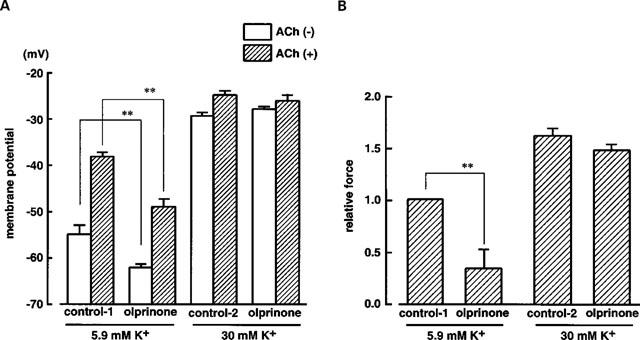

High K+ (30 mM) depolarized the membrane by 24.3±3.6 mV (n=3, Figure 3) and produced a contraction. The amplitude of the contraction was 0.72±0.18, when normalized with respect to the maximum contraction induced by 3 μM ACh (‘control-1' in Figure 3B) (n=3). In the presence of 30 mM K+, 3 μM ACh did not significantly modify the membrane potential (3.1±1.4 mV less negative, n=3, P>0.1) but it did increase the force (1.61±0.06 times control-1 in Figure 3B). In a solution containing 30 mM K+, olprinone (100 μM) modified neither the absolute membrane potential level nor the contraction whether these were measured in the absence or presence of 3 μM ACh (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of olprinone on ACh (3 μM)-induced depolarization and contraction in a solution containing either 5.9 mM K+ (normal K+ concentration in Krebs solution) or 30 mM K+. (A) shows membrane potential in the absence or presence of 3 μM ACh. Control-1 and Control-2 represent values obtained in the presence of 5.9 mM K+ or 30 mM K+, respectively, but without olprinone. (B) shows relative force evoked by ACh (3 μM). The maximum amplitude of contraction induced by 3 μM ACh in a solution containing 5.9 mM K+ was normalized as 1.0 (control-1). **P<0.01.

Effect of K+ channel blockers on the action of olprinone

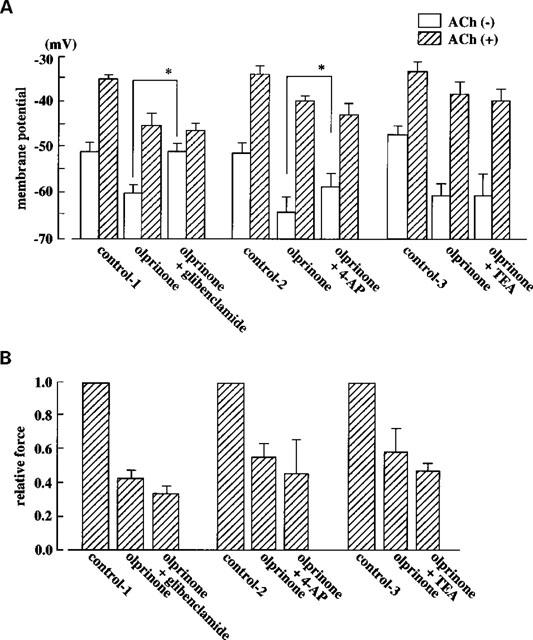

Various K+-channel inhibitors were applied in the presence of 100 μM olprinone (Figure 4). When the effect of glibenclamide (10 μM) was tested in the absence of olprinone, this agent did not modify the resting membrane potential (1.6±1.5 mV more negative, n=6, P>0.1). In the presence of 100 μM olprinone, glibenclamide (10 μM) depolarized the membrane (by 12.2±1.6 mV, n=9, P<0.01, Figures 1B and 4A) but modified neither the absolute membrane potential level reached in the presence of 3 μM ACh nor the concomitant contraction (Figure 4). However, when the effect of ACh in the presence of olprinone (100 μM) was expressed as an ACh-induced delta membrane potential, its value in the presence of 10 μM glibenclamide (6.4±1.3 mV) was significantly smaller than that in the presence of olprinone alone (15.2±1.8 mV, n=6, P<0.05) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Effects of glibenclamide (10 μM), 4-AP (1 mM) and TEA (1 mM) on the inhibitory action of olprinone on the effect of ACh on membrane potential and contraction. (A) Membrane potential recorded in the absence or presence of ACh with or without olprinone and with or without the K+ channel blockers. Control-1 represents the control data for the effects of olprinone (with or without glibenclamide), the series of responses being evoked in one and the same strip. Control-2 represents control data for the effect of olprinone (with or without 4-AP). Control-3 represents control data for the effect of olprinone (with or without TEA). (B) ACh (3 μM)-induced contractions expressed as relative force. Data are from the same three series of tests as those shown in (A). Each column shows the mean from 4–8 preparations with s.e.mean shown by vertical lines. *P<0.05.

In the presence of 100 μM olprinone, 4-AP (1 mM) slightly but significantly depolarized the membrane (by 7.7±1.1 mV, P<0.05, n=4). However, this agent (1 mM) did not modify the inhibitory action of 100 μM olprinone on the effect induced by 3 μM ACh (in the sense that neither the absolute membrane potential level nor the relative force achieved with ACh in the presence of olprinone differed whether 4-AP was or was not present) (n=4) (Figure 4). However, when the effect of ACh in the presence of olprinone (100 μM) was expressed as an ACh-induced delta membrane potential, it could be seen to be inhibited by 4-AP (23.9±4.2 mV and 14.9±5.2 mV in the absence and presence of 1 mM 4-AP, respectively, n=4, P<0.05) (Figure 4A).

In the presence of 100 μM olprinone, TEA (1 mM) did not modify the membrane potential. The absolute membrane potential level achieved with ACh, the ACh-induced delta membrane potential and the concomitant contraction were all unaffected by TEA (Figure 4).

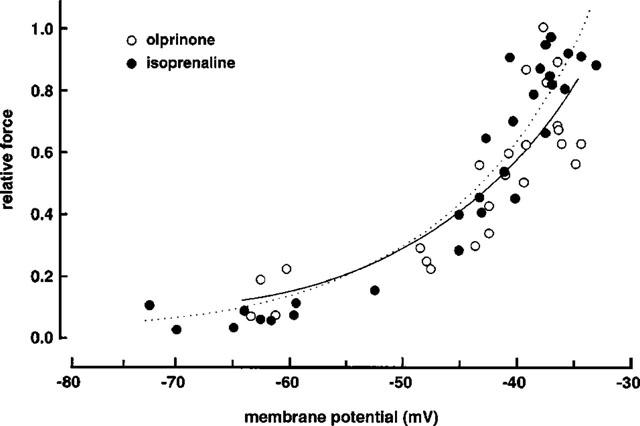

Relationship between membrane potential and relative force in the presence of olprinone

Figure 5 shows the relationship between membrane potential and relative force when 3 μM ACh was present together with various concentrations of either olprinone (1–100 μM) or isoprenaline (0.005–0.1 μM). In the presence of olprinone, the relationship was well fitted by a single exponential (log10 Fr=0.037Em+1.2, r=0.94, P<0.0001; Fr, relative force; Em, membrane potential). A similar result was obtained in the presence of isoprenaline (log10 Fr=0.039Em+1.4, r=0.96, P<0.0001). The parameters for these regression lines were not significantly different from each other (P>0.1).

Figure 5.

Relationship between membrane potential (Em) and relative force (Fr) in coronary arteries contracted with 3 μM ACh in the presence of olprinone (1–100 μM) or isoprenaline (0.005–0.1 μM). The maximum amplitude of contraction induced by 3 μM ACh with no olprinone and no isoprenaline was normalized as 1.0. Relative force (Fr) was calculated as log10Fr to correct for the non-linear relationship between Em and Fr.

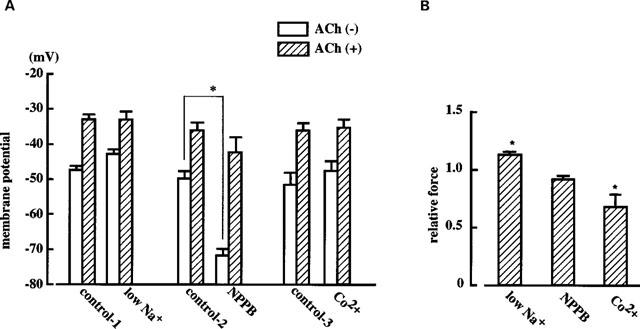

Effects of low Na+ solution, NPPB or Co2+ on ACh-induced membrane depolarization and contraction

In a solution containing low Na+ (15.5 mM), the resting membrane was slightly depolarized (by 4.7±0.9 mV, P<0.05, n=5). The absolute membrane potential level achieved in the presence of 3 μM ACh was not significantly modified by the low Na+ solution, but this solution slightly enhanced the ACh-induced contraction (Figure 6). The ACh (3 μM)-induced delta membrane potential was slightly attenuated by the low Na+ solution (13.4±0.4 mV in control and 10.5±1.0 mV in low Na+ solution, n=6, P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of low Na+ solution (15.5 mM), NPPB (10 μM) and Co2+ (2 mM) on ACh (3 μM)-induced membrane depolarization (A) and contraction (B) in endothelium-denuded rabbit coronary artery. (A) Membrane potential recorded in the absence or presence of ACh in strips treated or not treated with the various agents. Control-1 represents the control data for the effects of low Na+ solution, the series of responses being evoked in one and the same strip. Control-2 represents control data for NPPB and control-3 that for Co2+. (B) ACh (3 μM)-induced contractions expressed as relative force. Each column shows the mean from five preparations with s.e.mean shown by vertical lines. *P<0.05 vs the corresponding control (‘control' being a relative force of 1.0 in B).

NPPB (an inhibitor of Cl− channels, 10 μM) hyperpolarized the resting membrane (by 20.2±1.1 mV, n=4, P<0.01) but did not modify the absolute membrane potential level or contraction achieved in the presence of 3 μM ACh (Figure 6). The ACh (3 μM)-induced delta membrane potential was enhanced by NPPB (12.3±1.6 mV in control and 20.5±2.5 mV in NPPB, n=4, P<0.05).

Co2+ (an inhibitor of non-selective cation channels, 2 mM) modified neither the resting membrane potential nor the absolute membrane potential level reached in the presence of 3 μM ACh, but this agent did attenuate the ACh-induced contraction (to 0.69±0.10 times control, P<0.05, n=5) (Figure 6).

Discussion

In the present experiments, ACh (3 μM) depolarized the membrane and produced a contraction in the smooth muscle of the rabbit coronary artery. High K+ (30 mM) also depolarized the membrane and produced a contraction. Olprinone hyperpolarized the membrane and, in its presence, the absolute membrane potential level achieved with ACh was more negative than in its absence and the concomitant contraction was attenuated. This effect of olprinone was seen in a solution containing 5.9 mM K+ (normal Krebs solution) but not in a solution containing 30 mM K+. These results suggest that the absolute level of membrane potential attained in the presence of ACh plays an essential role in determining the effect of olprinone on the ACh-induced contraction.

It has been found (Ogawa et al., 1989; Sugioka et al., 1994) that olprinone selectively inhibits phosphodiesterase type III, an enzyme which preferentially catalyzes the hydrolysis of cyclic AMP in vascular smooth muscle, and causes a vascular relaxation via its effect on the intracellular level of cyclic AMP (Ohoka et al., 1990; Honda et al., 1994). The following mechanisms have been proposed to try to explain the vasorelaxation induced by cyclic AMP-increasing agents: (i) cyclic AMP repolarizes the smooth muscle cell membrane through an activation of K+ channels (Rembold & Chen, 1998), (ii) cyclic AMP inhibits intracellular Ca2+-mobilization through an activation of Ca2+-uptake into the cellular storage sites (Ito et al., 1993; Chen & Rembold, 1996) and (iii) cyclic AMP decreases myofilament Ca2+-sensitivity in vascular smooth muscle (Van Riper et al., 1995). It has recently been suggested that all of these mechanisms operate to mediate the relaxation induced by forskolin (a direct activator of adenylyl cyclase) during a contraction of the rat tail artery induced by 0.3 μM phenylephrine (Rembold & Chen, 1998). However, in the presence of a high concentration of phenylephrine (1 μM), forskolin inhibits the contraction mainly by decreasing the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Rembold and Chen, 1998) and the contribution made by this mechanism to olprinone-induced vascular relaxation has been noted in the same preparation (Tajimi et al., 1991). In the present experiments on the rabbit coronary artery, however, we found that olprinone did not inhibit the high-K+-induced contraction and that the inhibitory action of this agent on the ACh-induced contraction was completely abolished in a solution containing high K+. Furthermore, in the present study a relatively low concentration of isoprenaline (0.005–0.1 μM, a β-receptor stimulant) inhibited the ACh-induced membrane depolarization and contraction, and under these conditions, the correlation between the membrane potential and contraction was similar to that observed in the presence of 3 μM ACh with olprinone (10–100 μM). These results suggest that in the rabbit coronary artery, administration of olprinone increases cyclic AMP and leads to a situation in which the absolute membrane potential level achieved with ACh is more negative than in the absence of olprinone.

It was previously found in the canine saphenous vein that isoprenaline hyperpolarized the membrane and that this action was blocked by glibenclamide (a selective inhibitor of ATP-sensitive K+ channels) (Nakashima & Vanhoutte, 1995). It has also been found that cyclic AMP activates ATP-sensitive K+ channels via an activation of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in various types of vascular smooth muscle cells (Miyoshi & Nakaya, 1993; Randall & McCulloch, 1995; Ming et al., 1997; Schubert et al., 1997). In the present experiments, olprinone hyperpolarized the resting membrane and glibenclamide inhibited this olprinone-induced response, although glibenclamide did not modify the resting membrane potential (i.e. in the absence of olprinone). Furthermore, 4-AP depolarized the membrane only in the presence of olprinone. This may also be due to an inhibition of KATP channels, because at the concentration of 4-AP used, this drug inhibits not only the delayed rectifier K+ channels but also KATP channels (Nelson & Quayle, 1995). These results suggest that olprinone produces a resting membrane hyperpolarization in the smooth muscle of the rabbit coronary artery through an activation of glibenclamide-sensitive, ATP-sensitive K+ channels, possibly due to an action of cyclic AMP. However, we also found that glibenclamide did not modify the olprinone-induced effect on the absolute level of membrane potential achieved with ACh. These results suggest that in the smooth muscle of the rabbit coronary artery, while the glibenclamide-sensitive, ATP-sensitive K+ channel contributes to the olprinone-induced resting membrane hyperpolarization, this mechanism is not involved in the action of olprinone that effectively produces a relative hyperpolarization in the presence of ACh. Since neither TEA nor 4-AP modified this action of olprinone, the involvement of TEA- and 4-APsensitive K+ channels seems unlikely. Furthermore, solutions containing Co2+, low Na+ or NPPB all failed to modify the ACh-induced membrane depolarization (as assessed using the absolute membrane potential level as the index) although Co2+ did attenuate the ACh-induced contraction. These results suggest that non-selective cation channels, Na+ channels and Cl− channels do not individually make a major contribution to the ACh-induced membrane depolarization. Thus, in the rabbit coronary artery the inhibitory action of olprinone on the ACh-induced membrane depolarization is likely to involve mechanisms (such as pumps or ion exchangers) other than the opening or closing of channels selective for K+, cations or Cl−. This issue remains to be clarified.

In conclusion, in the smooth muscle of the rabbit coronary artery, olprinone produced a resting membrane hyperpolarization. It also attenuated the depolarizing effect of ACh (as assessed using the absolute membrane potential level as the index) and reduced the ACh-induced contraction. It is suggested that olprinone's inhibition of the ACh-induced contraction is due to this attenuation of the depolarizing effect of ACh. It is also suggested that while the glibenclamide-sensitive, ATP-sensitive K+ channel contributes to the membrane hyperpolarization induced by olprinone, this channel is not responsible for the olprinone-induced attenuation of the effect of ACh on membrane potential and smooth muscle tension.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr R. J. Timms for a critical reading of the English and J. Kajikuri and T. Kamiya for technical support. This work was partly supported by a Grant-In-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education of Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan. Olprinone was a gift from Eisai Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- NPPB

5-nitro-2-(3-phenyl-propylamino) benzoic acid

- PDE III

phosphodiesterase type III

- TEA

tetraethylammonium chloride

References

- CHEN X.L., REMBOLD C.M. Nitroglycerin relaxes rat tail artery primarily by decreasing [Ca2+]i sensitivity and partially by repolarization and inhibiting Ca2+ release. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H962–H968. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONDA M., KURAMOCHI T., ISHINAGA Y., KUZUO H., TANAKA K., MORIOKA S., ENOMOTO K., TAKABATAKE T. Contrasting effects of isoproterenol and phosphodiesterase III inhibitor on intracellular calcium transients in cardiac myocytes from failing hearts. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1994;21:1001–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1994.tb02663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO S., SUZUKI S., ITOH T. Effects of a water-soluble forskolin derivative (NKH477) and a membrane-permeable cyclic AMP analogue on noradrenaline-induced Ca2+ mobilization in smooth muscle of rabbit mesenteric artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13930.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITOH H., KUSAGAWA M., SHIMOMURA A., SUGA T., ITO M., KONISHI T., NAKANO T. Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent vasorelaxation induced by cardiotonic phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;240:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90545-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MING Z., PARENT R., LAVALÉE M. β2-adrenergic dilation of resistance coronary vessels involves KATP channels and nitric oxide in conscious dogs. Circulation. 1997;95:1568–1576. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYOSHI H., NAKAYA Y. Activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cultured smooth muscle cells of porcine coronary artery. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;193:240–247. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKASHIMA M., VANHOUTTE P.M. Isoproterenol causes hyperpolarization through opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle of the canine saphenous vein. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;272:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON M.T., QUAYLE J.M. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OGAWA T., OHHARA H., TSUNODA H., KUROKI J., SHOJI T. Cardiovascular effects of the new cardiotonic agent 1,2-dihydro-6-methyl - 2 - oxo -5 -(imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-6-yl)-3-pyridine carbonitrile hydrochloride monohydrate. Arzneim.-Forsch./Drug. Res. 1989;39:33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHHARA H., OGAWA T., TAKEDA M., KATOH H., DAIKU Y., IGARASHI T. Cardiovascular effects of the new cardiotonic agent 1,2-dihydro-6-methyl-2-oxo-5-(imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-6-yl)-3-pyridine carbonitrile hydrochloride monohydrate. Arzneim.-Forsch./Drug. Res. 1989;39:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHOKA M., HONDA M., MORIOKA S., ISHIKAWA S., NAKAYAMA K., YAMORI Y., MORIYAMA K. Effects of E-1020, a new cyclic AMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor, on cyclic AMP and cytosolic free calcium of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Jpn. Circ. J. 1990;54:679–687. doi: 10.1253/jcj.54.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANDALL M.D., MCCULLOCH A.I. The involvement of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in β-adrenoceptor-mediated vasorelaxation in the rat isolated mesenteric arterial bed. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:607–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14975.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REMBOLD C.M., CHEN X.L. Mechanisms responsible for forskolin-induced relaxation of rat tail artery. Hypertension. 1998;31:872–877. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.3.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUBERT R, , SEREBRYAKOV V.N., MEWES H., HOPP H.H. Iloprost dilates rat small arteries: role of KATP- and KCa-channel activation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:H1147–H1156. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.3.H1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGIOKA M., ITO M., MASUOKA H., ICHIKAWA K., KONISHI T., TANAKA T., NAKANO T. Identification and characterization of isoenzymes of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase in human kidney and heart, and the effects of new cardiotonic agents on these isoenzymes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1994;350:284–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00175034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAJIMI M., OZAKI H., SATO K., KARAKI H. Effect of a novel inhibitor of cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase, E-1020, on cytosolic Ca++ level and contraction in vascular smooth muscle. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1991;344:602–610. doi: 10.1007/BF00170659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAOKA H., TAKEUCHI M., ODAKE M., HAYASHI Y., MORI M., HATA K., YOKOYAMA M. Comparison of the effects on arterial-ventricular coupling between phosphodiesterase inhibitor and dobutamine in the diseased human heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993;22:598–606. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN RIPER D.A., WEAVER B.A., STULL J.T., REMBOLD C.M. Myosin light chain kinase phosphorylation in swine carotid artery contraction and relaxation. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:H2466–H2475. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.6.H2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]