Abstract

The slowly activating delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs) was recorded in single myocytes dissociated from guinea-pig ventricles and the mechanism underlying the block of IKs by a chromanol derivative, 293B, was investigated.

In the presence of 1–100 μM 293B, activation phase of IKs was followed by a slower decay during 10 s depolarizing pulses. Both the rate and extent of the decay were increased in a concentration-dependent manner.

The relationship between the concentration of 293B and the block showed a Hill's coefficient of approximately 1. The half-inhibitory concentration was approximately 3.0 μM and did not differ significantly at various membrane potentials from +20 to +80 mV.

A mathematical model for the 293B block was constructed on the basis of multiple closed and open states for the IKs channels, and the blocking rate was calculated by fitting the model to the original current traces. The blocking rate constant showed a linear function with the 293B concentration, indicating 1 : 1 binding stoichiometry. At +80 mV the blocking rate was 4×104 M−1 s−1 and the unblocking rate was 0.2 s−1.

The results indicate that 293B is an open channel blocker with relatively smaller blocking rate than those reported so far for time-dependent blockade of various ionic channels.

Keywords: Chromanol derivative, 293B, delayed rectifier K+ current, slowly activating IK, KvLQT1, IsK regulator, minK

Introduction

The delayed rectifier K+ current (IK) in cardiac cells consists of fast and slow components, i.e., the rapidly activating IK (IKr) and the slowly activating IK (IKs) (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990). The currents play a role for repolarizing the membrane after the plateau of the action potential. Since the prolongation of the plateau duration is thought to cause the prolongation of refractoriness, a number of pharmacological agents, which block IK, has been developed to achieve antiarrhythmic effect. For example, class III antiarrhythmic agents such as d-sotalol, E4031 and dofetilide are thought to block IKr, thereby causing prolongation of the action potential duration (Roden, 1993; Spector et al., 1996). However, class III antiarrhythmic agents targeted to IKr often cause an excessive prolongation, thereby leading to torsades de pointes arrhythmias (Roden, 1993).

On the other hand, it has been shown that a chromanol derivative, 293B, blocks IKs without affecting IKr or L-type Ca2+ current (Busch et al., 1996; Bosch et al., 1998). Since IKr and IKs possess different gating properties and voltage dependency (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990), it may be possible that the IKs block elicits antiarrhythmic action without unfavourable property observed in IKr blockers (Roden, 1993; Spector et al., 1996). More recently, Loussouarn et al. (1997) demonstrated that 293B is a potent blocker of human KvLQT1 channels and binds to the channel protein itself but not to the IsK (also termed minK) regulator. They showed that 293B blocks KvLQT1 in time- and voltage-dependent manner, and that the rate of the block differs between KvLQT1 current and the current expressed by KvLQT1 plus IsK regulator. The finding indicates that the blocking rate or voltage-dependency might be different in native IKs, which consists of KvLQT1 and IsK regulator with unknown stoichiometry (Barhanin et al., 1996; Sanguinetti, et al., 1996). However, systematic analysis for 293B block of native IKs such as voltage-dependency and the block kinetics has not been carried out. In the present study, therefore, we investigated the effects of 293B on IKs in guinea-pig ventricular cells, and the time-dependency of the blocking rate was determined for 293B.

Methods

Cell isolation

Ventricular cells were isolated from hearts of guinea-pig (300–400 g body weights) using the enzymatic dissociation technique (Isenberg & Klöckner, 1982; Shinbo & Iijima, 1997). Guinea-pigs were anaesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1) and the chest was opened under the artificial respiration. The heart was dissected out and the ascending aorta was cannulated to start coronary perfusion with the control Tyrode solution. After perfusing with 100 ml Ca2+-free Tyrode solution, the perfusate was switched to a Ca2+-free Tyrode solution containing collagenase (0.02%, Wako, Osaka, Japan), and the heart was digested for about 30 min. Then the heart was rinsed with a high K+, low Cl− storage solution. The left ventricle was dissected from the digested heart, and stored in the storage solution at 4°C for later use.

A small piece of the ventricular tissue was dissected and gently agitated in the recording chamber (0.5 ml in volume) filled with the normal Tyrode solution. After the cells had settled on the floor of the recording chamber, they were perfused with normal Tyrode solution at 2–3 ml min−1. Experiments were performed at 36–37°C on rod-shaped quiescent single cells that had clear sarcomere striations.

Solutions and drugs

The control Tyrode solution contained (in mM): NaCl 136.9, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 0.53, NaH2PO4 0.33, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulphonic acid (HEPES) 5.0, and glucose 5.5, (pH=7.4, adjusted with NaOH). The standard external solution was made by adding 0.3 μM nisoldipine to the control Tyrode solution in order to block the L-type Ca2+ current. The Ca2+-free external solution was made by omitting CaCl2 from the standard external solution. The high K+, low Cl− storage solution contained (in mM): taurine 10, oxalic acid 10, L-glutamic acid 70, KCl 25, KH2PO4 10, EGTA 0.5, glucose 11, and HEPES 10 (pH=7.4, adjusted with KOH). The pipette solution contained (in mM): K-aspartate 110, KCl 20, K2ATP, K2-creatine phosphate 6, MgCl2 2, HEPES 5, EGTA 10 (pH=7.0, adjusted with KOH).

293B was kindly donated by Hoechst Co. Ltd (Frankfurt, Germany). 293B was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) as a 10 mM stock solution, and diluted in the bath solution to give each concentration described in the text. The final concentration of DMSO to which cells were exposed was less than 0.03%. E4031, a selective blocker for IKr, was donated by Eisai Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), and dissolved in distilled water as a 1 mM stock solution and was then added to the bath solution to give the concentration as described in the text.

Electrophysiological experiments

The patch clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981) was used to record whole-cell currents using a patch clamp amplifier (EPC-7, List, Darmstadt, Germany). Patch pipettes were pulled with a micropipette puller (Model P-97, Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, U.S.A.) from glass capillaries (Corning #7052; Warner Instrument Co., CT, U.S.A.), and the electrode resistance ranged 3–5 MΩ. The data were digitized at 2–10 kHz into an IBM-compatible computer (Proside, Tokyo, Japan) using the pClamp software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.).

Statistical values are given in mean±s.e.mean. Comparisons between two groups were performed by paired or unpaired Student's t-test. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

293B blocks not only IKs but also IKr

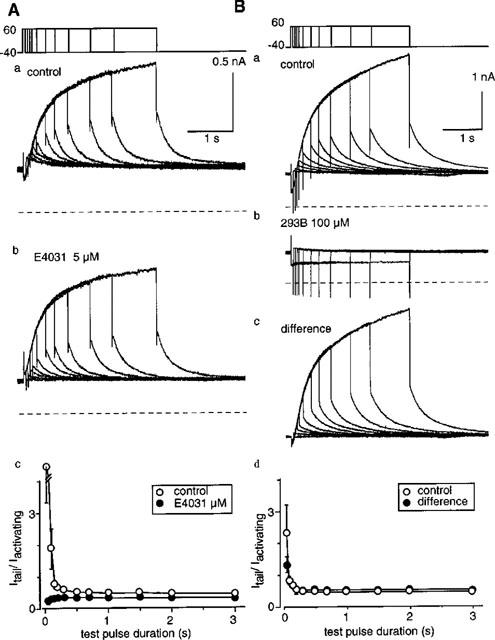

In guinea-pig ventricular cells, not only IKs but also IKr exists (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990). In the experiment shown in Figure 1A, the membrane was depolarized to +60 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV in the standard external solution (a) or in the external solution containing 5 μM E4031 (b), and current recordings with different pulse durations were superimposed. In the control, tail current developed more rapidly than time-dependent outward current during the depolarizing pulse, probably due to the presence of IKr. In the presence of E4031, however, the envelope time course of the tail current corresponded closely to the time course of outward current during the depolarizing pulse. This is clearly shown in Figure 1Ac where the ratio of the tail amplitude relative to the outward current during the conditioning pulse, obtained from six cells, was plotted against the pulse duration. The ratio was initially large in the control (open circles) whereas it was almost constant in the presence of E4031 (filled circles). The finding confirmed the selective blockage of IKr by E4031 (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of IKs and IKr by 293B in guinea-pig ventricular cells. (A) An envelope test of tail currents. Superimposed current traces were obtained when the membrane was depolarized from −40 mV to +60 mV for various duration in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 5 μM E4031. The dotted lines indicate zero current level. (c), The ratio of tail current to time-dependent current. The data are average of six experiments and bars indicate s.e.mean. No bars are shown when the s.e.mean is smaller than the symbol size. (B) An envelope test of tail currents in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 100 μM 293B. The dotted lines indicate zero current level. (c), the 293B-sensitive current was measured by subtracting the current in the presence of 293B (b) from the control (a). (d), The ratio of tail current to time-dependent current. The data are average of three experiments.

The same pulse protocol was applied to examine the effect of 293B on IKs and IKr (Figure 1B). After obtaining a control envelope test in the standard external solution (Figure 1Ba), 100 μM 293B was applied. In the presence of 293B (Figure 1Bb), both outwardly activating current and tail current were markedly suppressed, except for relatively short pulse durations where small tail currents were still observed. This indicates that the 293B-sensitive current (c), obtained by subtracting the current in the presence of 293B (b) from the control current (a), includes the current component attributable to IKr. In fact, the ratio of the tail amplitude to the outward current (d), measured for the 293B-sensitive current, was not constant during the conditioning pulse and showed an initial peak (filled circles) although in a smaller extent than that of the control (open circles). Thus, 293B appeared to inhibit not only IKs but also IKr. In order to examine the mechanism of IKs block by 293B, following experiments were carried out in the presence of 5 μM E4031.

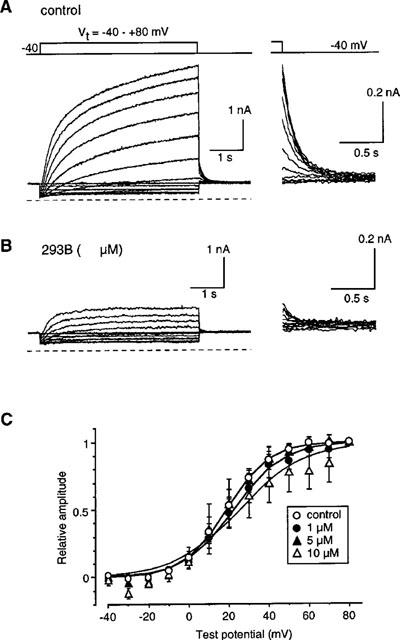

Steady-state activation of IKs

The effects of 293B on the steady-state activation of IKs were examined. In the experiment shown in Figure 2, a 5 s depolarizing pulse was applied from −40 mV to various potentials in 10 mV increment in the absence (A) and presence of 10 μM 293B (B). To obtain the steady-state activation, the amplitude of the tail current was measured, normalized in reference to the maximum amplitude for the drug concentration given, and plotted against the test potentials (Figure 2C). For each concentration of 293B, four to six cells were examined. The smooth curves were drawn by the least squares fit with the Boltzmann equation,

where V1/2 and S indicate the half-activation voltage and the slope factor, respectively. On average, the value of V1/2 was 18.76±3.16 mV (n=6) in the control, 23.56±4.92 mV (n=4) at 1 μM, 18.70±4.97 mV (n=5) at 5 μM, and 27.63±8.30 mV (n=4) at 10 μM 293B. The value of S was 10.10±0.78 mV in the control, 10.63±1.90 mV at 1 μM, 10.00±0.67 at 5 μM, and 16.03±4.93 mV at 10 μM 293B. Thus, 293B inhibits IKs without affecting its kinetics.

Figure 2.

Voltage-dependent activation of IKs. (A) A 5-s depolarizing pulse was applied every 30 s from −40 mV to various test potentials in 10 mV increment. Superimposed current traces were recorded in the standard external solution containing 0.3 μM nisoldipine. Five μM E4031 was added to the external solution to block IKr. The dotted line indicates the zero current level. Right-hand panel; tail currents are shown on an expanded time scale. (B) The same pulse protocol was repeated in the presence of 10 μM 293B. (C) The relationship between the test potential and the tail amplitude at different [293B]o. The amplitude of the tail current was normalized to the maximum amplitude for the given concentration of 293B. Data are average of 4–6 experiments and bars indicate s.e.mean. The smooth curves were drawn by the least squares fit with the Boltzmann equation, I=1/(1+exp((V−V1/2)/S)), where V1/2 and S indicate the half-activation voltage and the slope factor, respectively. For details, see text.

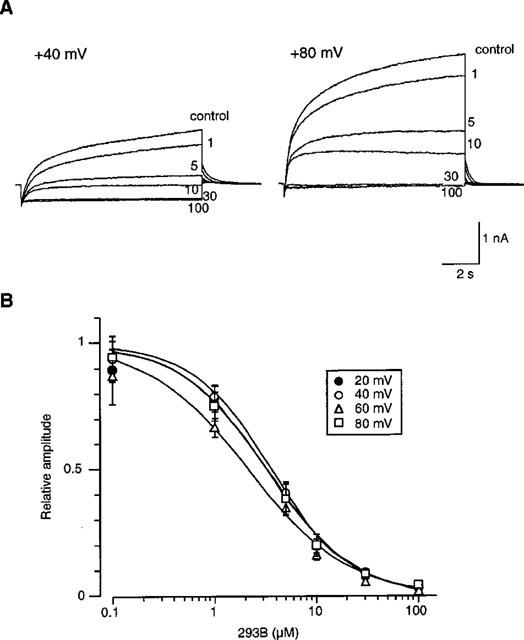

Concentration-response relationship for the 293B block

Current records obtained at different extracellular concentrations of 293B ([293B]o) were compared at +40 mV and +80 mV (Figure 3). The blocking effect of 293B became evident around 0.1 μM and was almost saturated at 100 μM. At lower [293B]o the configuration of IKs was not obviously altered by 293B. But, increasing [293B]o, a time-dependent inhibition of IKs was revealed. For example, at 5 or 10 μM 293B the initial activation time course of IKs were almost superimposable on the control, and thereafter the current was time-dependently depressed.

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of IKs by 293B. (A) A 10 s depolarizing pulse from −40 mV to either +40 mV (left panel) or +80 mV (right panel) was repeated every 1 min. Superimposed current traces were recorded at different [293B]o. Numerals indicate [293B]o in μM. (B) The relationship between the IKs amplitude and [293B]o, obtained at different [293B]o. The amplitude of time-dependent outward current during the test pulse was normalized to that of the control current. Data are average of 5–8 experiments, and bars indicate s.e.mean. No bars are shown when the s.e.mean is smaller than the symbol size. Filled circles, +20 mV; open circles; +40 mV; open triangles, +60 mV; open squares, +80 mV. The smooth curves were drawn by the least squares fit with the equation, I=1/(1+([293B]o/IC50)n), where IC50 and n indicate the half-inhibitory concentration and the Hill's coefficient, respectively. For details, see text.

The [293B]o-block relationship was constructed by measuring the current level near the end of depolarizing pulse. The current amplitudes were normalized referring to those obtained in the absence of 293B, and results were summarized in Figure 3B. The smooth curves were drawn by the least squares fit with the equation,

where IC50 and n indicate the half-inhibitory concentration and the Hill's coefficient, respectively. The IC50 value was 3.17±0.93 (n=7) at +20 mV (filled circles), 3.54±0.57 (n=5) at +40 mV (open circles), 2.11±0.39 (n=8) at +60 mV (open triangles) and 3.24±0.85 (n=5) +80 mV (open squares). The n value was 1.08±0.15 at +20 mV, 1.27±0.16 at +40 mV, 0.91±0.06 at +60 mV and 1.11±0.09 at +80 mV. Thus, no significant voltage-dependency could be detected.

Time-dependent block of IKs by 293B

To confirm the time-dependent block of 293B, IKs recorded during a depolarizing step to +40 mV in the presence of 293B was digitally divided by the current recorded in control (i293B/icont). This calculation gave a relative amount of unblocked IKs as a function of time during a depolarizing step (Figure 4A). It was clearly shown that the 293B block became faster and the extent of the block became larger, as [293B]o was increased.

Figure 4.

Time-dependent block of IKs by 293B. (A) A 10 s pulse from −40 mV to +40 mV was applied every 1 min. Time-dependent outward current during a depolarizing step at different [293B]o was digitally divided by the current in the absence of 293B (i293B/icont) and superimposed. (B) The same calculation was performed for tail current. Numerals indicate [293B]o in μM. In the inset, original traces of tail current are shown.

The same analysis was carried out for the tail current at −40 mV (Figure 4B). In the case of the tail current, i293B/icont should represent the time course of unblock. At 1, 5, 10 μM [293B]o, i293B/icont decreased transiently, and thereafter increased for approximately 4 s. At higher concentrations, i293B/icont showed a continuous increase and became saturated within 4 s. These findings indicate that the time course of recovery was determined by the extent of the block during the preceding depolarization.

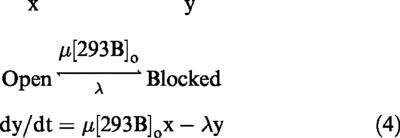

Mathematical model for the block of IKs by 293B

The time-dependent block of IKs by 293B indicates that 293B acts as an open channel blocker for IKs. In order to determine the block and unblock kinetics, a mathematical model was used. It has been reported that IKs consists of several closed states and an open state (Balser et al., 1990). Thus, the state transitions between the closed and open states can be described as, C1-C2 - - - - - Cn-Open where C(n) is the nth closed confirmation. In the present study, the time course of activation of IKs in the absence of the blocker was well fitted with the sum of two exponential functions, and therefore the time course of the open conformation without 293B can be approximated as

where τ1 and τ2 are the time constants of the fast and slow components, respectively, and A and B are the proportion of each component in the steady state. Provided that 293B binds to the open state, the blocking model can be described as

|

where x and y represent the open and the block confirmation, respectively. A general equation describing the time-dependent change of the open conformation can be given, assuming that

That is, the fraction of channels in the open states (x) and fraction of blocked channels (y) would give the fraction of the channels (z) which are normally open. The solution of these equations for x is given as:

|

where τb=1/(μ[293B]o+λ), y∞=μ[293B]o/(μ[293B)o+λ), P=Ay∞/(1−τb/τ1), Q=B y∞/(1−τb/τ2) and S=P+Q-y∞/(A+B). Thus, the time course of IKs in the presence of 293B could be fitted by the sum of three exponential functions.

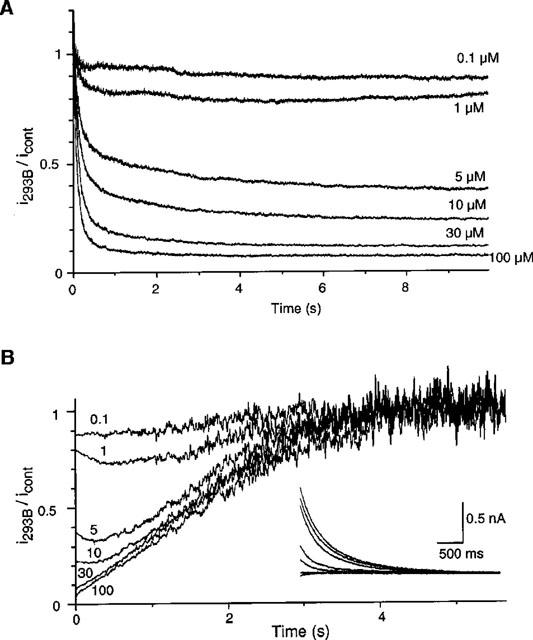

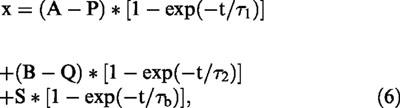

Figure 5 shows an example of fitting equation. 6 to the IKs recordings are +60 mV at different [293B]o. First fitting the control of IKs to equation. 3 yields values for τ1 and τ2 to 0.23 and 3.61 s, respectively. These values were then included in equation. 6 and IKs in the presence of 293B fitted to the equation using the least-squares method. The values of τb, thus obtained form four cells, were shown in Figure 5B, where the reciprocal of τb (τb−1) was plotted against [293B]o. At various test potentials a linear relation is evident, supporting 1 : 1 binding stoichiometry.

Figure 5.

A mathematical model for the blockade of IKs by 293B. (A) Superimposed current traces (dotted lines) were obtained by applying a 10 s depolarizing pulse from −40 mV to +60 mV in the absence and presence of 1 or 5 μM 293B. In the control, the current was fitted to the sum of two exponential functions with time constants of 0.23 and 3.61 s (smooth curve). In the presence of 293B, the smooth curves represent the least-squares fit of Equation 6. (See text for details). (B) The relationship between the reciprocal time constant (τb−1) and [293B]o. The lines represent the least squares fit at different membrane potentials.

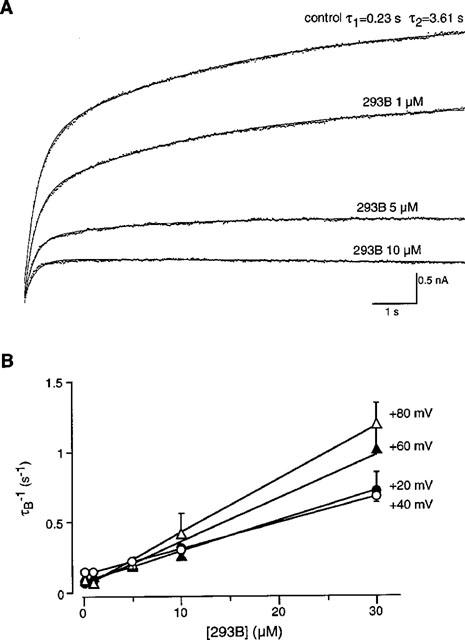

We then obtained the blocking (μ) and unblocking (λ) rate constants from the linear relation. The values of μ, λ and the ratio λ/μ were plotted at different membrane potentials (Figure 6). The blocking rate constant, μ, increased with membrane depolarization, and the regression line had a slope of an e-fold increase per 80.9 mV. On the other hand, the unblocking rate, λ, seemed to be constant at different membrane potentials. As a result, the ratio λ/μ was almost constant at potentials more positive than +40 mV (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Voltage dependency of the blocking and unblocking rates of 293B. (A) The relationship between the blocking rate (μ) and the membrane potential. The line indicates the least squares fit with a slope of an e-fold increase per 80.9 mV. (B) The relationship between the unblocking rate (λ) and the membrane potential. (C) The relationship between the dissociation constant (λ/μ) and the membrane potential.

Effect of 293B on IKr

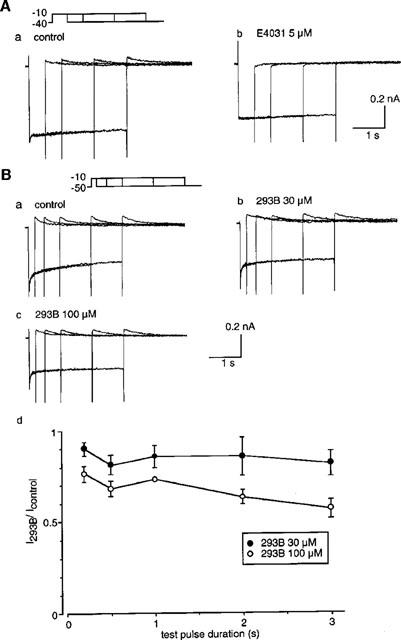

In the absence of E4031, 100 μM 293B inhibited the time-dependent outward current in response to depolarizing pulse and only small tail currents were observed upon relatively short pulse durations (Figure 1). Furthermore, the tail current was almost completely abolished during the prolonged depolarization (Figure 1). The findings may indicate that IKr is also blocked by 293B in a time-dependent manner. This property is particularly important when 293B is used as a tool to elucidate the physiological role of IKs in cardiac myocytes. Therefore the experiments were designed to examine whether 293B blocks IKr or not. It is known that in Ca2+-free external solutions activation of IKr is shifted to more negative potentials and IKs activation moved more positive potentials (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1992). Under these conditions current evoked by a depolarizing pulse to −10 mV from −40 or −50 mV seems predominantly IKr. This is demonstrated in Figure 7A, where the membrane was depolarized to −10 mV from −40 mV in the Ca2+-free external solution, and current recordings with different pulse durations were superimposed. In control (a), the current shifted initially to downward direction upon depolarization, probably due to the lack of the inward rectifier K+ current at −10 mV, and thereafter activation of IKr was observed. The tail current at repolarization was almost constant irrespective of different pulse durations in control (Aa), and was completely abolished by 5 μM E4031 (Ab). On the other hand, application of 30 μM (Bb) and 100 μM (Bc) 293B affected the tail current, although only slightly, in a concentration dependent manner. It should be noticed that the outward current during the depolarization was also depressed in a time-dependent manner by 293B. The amplitude of the tail current in the presence of 293B was normalized to that in control and plotted in Figure 7Bd. These findings indicate that high concentrations of 293B inhibit, although only slightly, IKr in a time-dependent manner.

Figure 7.

Effects of 293B on IKr. (A) An envelope test of tail currents. Superimposed current traces were obtained when the membrane was depolarized from −40 mV to −10 mV for various duration in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 5 μM E4031. The external solution is Ca2+-free. (B) An envelope test of tail currents in the absence (a) and presence of 30 μM (b) 100 μM (c) 293B. The holding potential is −50 mV. (d) The amplitude of the tail current in the presence of 293B was normalized to that in the absence of drug and plotted against the pulse duration. The data are average of three experiments.

Discussion

In response to a depolarizing pulse, the initial activation time course of IKs was overlapped irrespective of whether 293B exists or not, and thereafter the block occurred in a time-dependent manner. The extent of the block becomes larger and the rate of the block faster as [293B]o increases. Upon repolarization to −40 mV after preceding depolarization, i293B/icont decreased transiently at moderate concentrations of 293B. The finding can be explained by assuming that the unblocking rate at the holding potential is relatively faster than the deactivation rate of IKs, i.e., the rapid unblock of the channel transiently increases the fraction of the open conformation upon repolarization. Thus, the findings obtained in the present study are consistent with a view that 293B is an open channel blocker for IKs (Loussouarn et al., 1997). Alternatively, 293B may bind to a certain site of the channel in a state-dependent manner, i.e., 293B binds to the channel with the open conformation and unbinds if the channel is in the closed conformation.

IKs is known to consist of at least two different subunits, i.e., KvLQT1 channels and IsK regulator (Barhanin et al., 1996; Sanguinetti, et al., 1996). It has veen recently shown that 293B is a potent blocker of human KvLQT1 channels and binds to the channel protein itself but not to the IsK regulator (Loussouarn et al., 1997). In COS-7 cells expressing KvLQT1 alone (without IsK), 293B blocked KvLQT1 current in both voltage- and time-dependent manner (Loussouarn et al., 1997). In the present study, however, the IC50 values did not exert clear voltage-dependency over the voltage range from +20 to +80 mV. The difference is, in part, due to the voltage range examined. In the case of KvLQT1, the voltage-dependency of IC50 values was detected at potentials more negative than 0 mV (Loussouarn et al., 1997), whereas we could not measure the [293B]o-IKs block relationship at such negative potentials because the current size is very small in native IKs. In addition, it is well known that coexpression of IsK regulator with KvLQT1 slows activation kinetics of KvLQT1 (Barhanin et al., 1996; Sanguinetti et al., 1996; Romey et al., 1997). It is thus speculated that IsK regulator may alter the binding- or unbinding-rate of 293B, thereby blunting the voltage-dependency for IKs. In fact, Loussouarn et al. (1997) showed that 293B block takes a few tenths of ms in the absence of IsK and a few hundredths of ms in the presence of IsK.

On the other hand, the model calculation showed that the blocking rate increased with depolarization. The voltage-dependent block can be described by the following equation (Woodhull, 1973),

Where μ0 indicates the blocking rate at 0 mV, and z, F, E, R and T have their usual meanings in thermodynamics. When the above equation was applied to the voltage-dependency of the blocking rate (Figure 7), the values of μ0 and δz were obtained to be 1.44×104 M−1 s−1 and 0.30. These values are relatively smaller in comparison to the rate constants for the ion block of other ionic channels in previous studies. For example, the rates of Mg2+ block of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel and the inward rectifier K+ channel are reported to be 1.5–2.0×107 M−1 s−1 (Horie et al., 1987) and 1.1×105 M−1 s−1, (Ishihara et al., 1989) respectively. The rate constant for the Cs+ and Rb+ block of the inward rectifier K+ current are 4×106 and 106 M−1 s−1 (Matsuda et al., 1989) respectively. On the other hand, much slower rate constant has been reported for the Sr2+ block of the hyperpolarization-activated cation channel, i.e., the rate is 6.4 M−1 s−1 (Ono et al., 1994).

To determine the blocking- and unblocking-rate, we used a mathematical model with an assumption that the fraction of the closed channels does not change after the addition of the blocker. Using an essentially similar calculation, Ono et al. (1994) characterized the time- and voltage-dependent block by Sr2+ of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current in rabbit sinoatrial node cells. They showed that the observed values such as blocking rate and dissociation constant were in agreement with those obtained by the concentration-jump method (Ono et al., 1994). It should be noticed, however, that the above assumption may lead to under- or over-estimation of the block kinetics. At strong depolarization where the probability of channels staying in the closed states is negligibly small, the measurement of the rate constants might not be seriously affected. At moderate depolarization, however, the open probability is less than unity, and therefore the fraction of the closed channels should be affected by the presence of a blocked state. It should also be noted that the control IKs was fitted with the sum of two exponential functions in the present study. This fit does not necessarily represent the whole time course of IKs. This is because the onset of IKs is sigmoidal (Matsuura et al., 1987; Balser et al., 1990) and more than three closed states are considered to be present in the conformation of IKs channels (Balser et al., 1990). Thus, the measurement of block kinetics is still preliminary in the present study.

In the experiment designed to examine the effect of 293B on IKr (Figure 7) the tail current was depressed only slightly but in a time-dependent manner. The inhibition was observed at >30 μM. The finding might be in good agreement with a previous finding that 30 μM 293B exerted no significant effects on IKr of guinea-pig hearts during a 500 ms depolarizing pulse (Busch et al., 1997; Bosch et al., 1998). However, in the absence of E4031 and presence of 100 μM 293B, the tail current could be recorded only upon relatively short pulse durations, and was completely abolished during prolonged depolarization (Figure 1). The finding can not be explained unless 293B blocks IKr in a time-dependent manner. It may be speculated that 293B blocks IKr both in time- and voltage-dependent manner, i.e., depolarization to −10 mV inhibits the tail current slightly (Figure 7) but strong depolarization to +60 mV blocks IKr completely during the prolonged pulses as like that seen in Figure 1. In the present study, however, detailed measurement of block kinetics for IKr or use-dependency could not be carried out at various membrane potentials because the separation of IKr and IKs is difficult in native myocytes, particularly at positive potentials. Further study with a help of molecular biology is required to elucidate this point. Nonetheless, it seems that much higher concentrations of 293B are required to completely block IKr than those for IKs block. In addition, because of the slow kinetics the blocking effect of 293B on IKr might be negligible under the physiological condition where the action potential duration is usually less than a few hundredths of ms.

In conclusion, the present results indicate that 293B blocks IKs in native myocytes in a time-dependent manner. The blocking rate, measured by using a mathematical model, is relatively slower than those reported for open channel blockage of various ionic channels reported in previous studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miss M. Takahashi for her secretarial service. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, and from the Naitoh Memorial Foundation.

Abbreviations

- IK

delayed rectifier K+ current

- IKr

rapidly activating delayed rectifier K+ current

- IKs

slowly activating delayed rectifier K+ current

References

- BARHANIN J., LESAGE F., GUILLEMARE E., FINK M., LAZDUNSKI M., ROMEY G. KvLQT1 and IsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKS cardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–89. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BALSER J.R., BENNET P.B., RODEN D.M. Time-dependent outward current in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes: Gating kinetics of the delayed rectifier. J. Gen. Physiol. 1990;96:835–863. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.4.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOSCH R.F., GASPO R., BUSCH A.E., LANG H.J., LI G.R., NATTEL S. Effects of the chromanol 293B, a selective blocker of the of the slow component of the delayed rectifier K+ current, on repolarization in human and guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;38:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSCH A.E., SUESSBRICH H., WALDEGGER S., SAILER E., GREGER R., LANG H.-J., LANG F., GIBSON K., MAYLIE J.G. Inhibition of IKs in guinea pig cardiac myocytes and guinea pig IsK channels by the chromanol 293B. Pflügers Arch. 1996;432:1094–1096. doi: 10.1007/s004240050240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORIE M., IRISAWA H., NOMA A. Voltage-dependent magnesium block of adenosine-triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel in guinea-pig ventricular cells. J. Physiol. 1987;387:251–271. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISENBERG G., KLÖCKNER U. Calcium tolerant ventricular myocytes prepared by preincubation in a ‘KB Medium'. Pflügers Arch. 1982;395:6–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00584963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIHARA K., MITSUIYE T., NOMA A., TAKANO M. The Mg2+ block and intrinsic gating underlying inward rectification of the K+ current in guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. J. Physiol. 1989;419:297–320. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOUSSOUARN G., CHARPENTIER F., MOHAMMAD-PANAH R., KUNZELMANN K., BARO I., ESCANDE D. KvLQT1 potassium channel but not IsK is the molecular target for trans-6-cyano-4-(N - ethylsulfonyl - N-methylamino) - 3 - hydroxy -2,2-dimethyl-chromane. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:1131–1136. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.6.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA H., MATSUURA H., NOMA A. Triple-barrel structure of inwardly rectifying K+ channels revealed by Cs+ and Rb+ block in guinea-pig heart cells. J. Physiol. 1989;413:139–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUURA H., EHARA T., IMOTO Y. An analysis of the delayed outward current in single ventricular cells of the guinea-pig. Pflügers Arch. 1987;410:596–603. doi: 10.1007/BF00581319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONO K., MARUOKA F., NOMA A. Voltage- and time-dependent block of I(f) by Sr2+ in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. Pflügers Arch. 1994;427:437–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00374258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODEN D.M. Current status of class III antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1993;72:44B–49B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90040-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROMEY G., ATTALI B., CHOUABE C., ABITBOL I., GUILLEMARE E., BARHANIN J., LAZDUNSKI M. Molecular mechanism and functional significance of the MinK control of the KvLQT1 channel activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:16713–16716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANGUINETTI M.C., CURRAN M.E., SPECTOR P.S., ZOU A., SHEN J., ATKINSON D., KEATING M.T. Coassembly of KvLQT1 and minK (IsK) to form cardiac IKS potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANGUINETTI M.C., JURKIEWICZ N.K. Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. J. Gen. Physiol. 1990;347:641–657. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANGUINETTI M.C., JURKIEWICZ N.K. Role of external Ca2+ and K+ in gating of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ currents. Pflügers Arch. 1992;420:180–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00374988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHINBO A., IIJIMA T. Potentiation by nitric oxide of the ATP-sensitive K+ current induced by K+ channel openers in guinea-pig ventricular cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:1568–1574. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPECTOR P.S., CURRAN M.E., KEATING M.T., SANGUINETTI M.C. Class III antiarrhythmic drugs block HERG, a human cardiac delayed rectifier K+ channel. Circ. Res. 1996;78:499–503. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOODHULL A.M. Ionic blockage of sodium channels in nerve. J. Gen. Physiol. 1973;61:683–708. doi: 10.1085/jgp.61.6.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]