Abstract

We studied the functional interaction between transport and metabolism by comparing the transport of losartan and its active metabolite EXP 3174 (EXP) across cell monolayers.

Epithelial layers of Caco-2 cells as well as MDR1, MRP-1 and MRP-2 overexpressing cells, in comparison to the respective wildtypes, were used to characterize the transcellular transport of losartan and EXP.

Losartan transport in MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cells was saturable and energy-dependent with a significantly greater basolateral-to-apical (B/A) than apical-to-basolateral (A/B) flux (ratio=31±1 in MDCK-MDR1 and ratio 4±1 in Caco-2 cells). The B/A flux of losartan was inhibited by cyclosporine and vinblastine, inhibitors of P-glycoprotein and MRP. In contrast, no active losartan transport was observed in MRP-1 or MRP-2 overexpressing cells.

The metabolite was only transported in Caco-2 cells with a B/A-to-A/B ratio of 5±1, while lacking active transport in the MDR1, MRP-1 or MRP-2 overexpressing cells. The B/A flux of EXP was significantly inhibited by cyclosporine and vinblastine.

In conclusion, losartan is transported by P-glycoprotein and other intestinal transporters, that do not include MRP-1 and MRP-2. In contrast, the carboxylic acid metabolite is not a P-glycoprotein substrate, but displays considerably higher affinity for other transporters than losartan, that again most probably do not include MRP-1 and MRP-2.

Keywords: Angiotensin-II antagonists, intestinal drug transporters, P-glycoprotein, Caco-2 cells, MDCK-MDR1 cells

Introduction

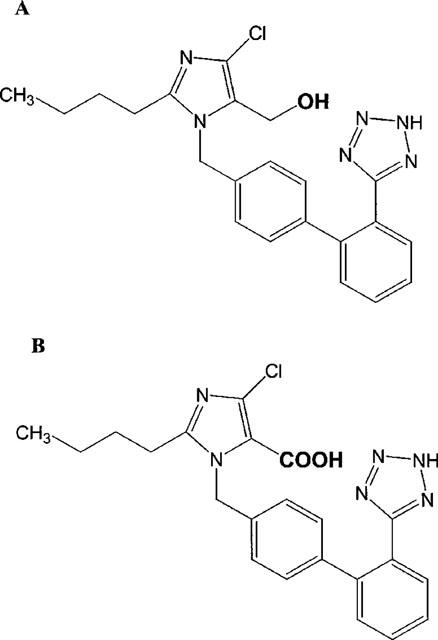

Losartan, the potassium salt of 4-chloro-5-hydroxymethyl-2-n-butyl-1-[(2′ -(1H -tetrazol -5 -yl)[1,1′-biphenyl -4-yl]methyl]-1H-imidazole is the prototype of a new generation of potent, orally active nonpeptide angiotensin-AT1 antagonists (Timmermans et al., 1993). Although losartan itself exerts good angiotensin-II blocking efficacy, its clinical hypotensive activity is predominantly mediated by its major active metabolite EXP 3174, 2-butyl-4-chloro-1-[2′-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)[1,1′-biphenyl-4-yl]methyl]-1H-imidazole-5-carboxylic acid, to which losartan is metabolized mainly by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9 and 3A4 enzymes (Figure 1) (Stearns et al., 1992; 1995; Wong et al., 1990).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of losartan (A) and EXP 3174 (B).

Losartan exhibits highly variable and low oral bioavailability (Lo et al., 1995). In the past, systemic bioavailability of orally administered drugs was considered primarily a function of physical drug absorption and first-pass metabolism in the liver (Aungst, 1993). However, it has recently been recognized that intestinal CYP3A-dependent metabolism and active intestinal counter-transport from the mucosa cell back into the gut lumen significantly contribute to the low and variable oral bioavailability of many drugs, most of which are known cytochrome P450 3A substrates (Benet et al., 1996; Wacher et al., 1995). In addition to phase-I metabolism, active secretion of absorbed drug by, particularly, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters such as P-glycoprotein and the multi-drug resistance-associated plasma membrane (MRP) transporter family, has been identified as an important determinant of oral drug bioavailability (Benet et al., 1996; Borst et al., 1997; Deeley & Cole, 1997). Since losartan is a CYP3A4 substrate, and has a low (mean 33%) and variable oral bioavailability (12.1–66.6%) (Lo et al., 1995), we hypothesize that, in addition to first-pass metabolism, intestinal counter-transport of losartan is a significant factor in the observed low oral losartan bioavailability.

Here, we compare transport of losartan with that of its metabolite EXP 3174.

Methods

Materials

Caco-2 cells (HTB-37) and Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK-I) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.). Human P-glycoprotein-overexpressing, stably MDR1-transfected Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK-MDR1) were kindly provided by Dr I. Pastan (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.) (Pastan et al., 1988). Human MRP-1 (LLC-MRP1) and MRP-2 (M2MO-217=MDCK-II-cMOAT17) overexpressing cell lines as well as the respective wildtype cells were a generous gift from Drs P. Borst and R. Evers (Evers et al., 1996; 1998).

Losartan and EXP 3174 were kindly provided by Merck Research Laboratories (Rahway, NJ, U.S.A.). Cyclosporine was a gift from Novartis Pharmaceuticals (Basle, Switzerland). Vinblastine, colchicine, HPLC-grade acetonitrile, sulphuric acid, sodium hydroxide and sodium dodecylsulphate were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). [14C]-Mannitol (51.5 Ci·mol−1) was purchased from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.). Cell culture media and supplements were obtained from the UCSF-Cell Culture Facility (San Francisco, CA, U.S.A.). Polycarbonate membrane inserts and 6-well plates were purchased from Corning Costar Corporation (Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.).

Cell cultures

All cells were grown at 37°C under 5% humidified CO2-atmosphere. Caco-2 cells (passages 30–40) were cultured in antibiotic-free Minimum Essential Eagle's Medium (MEM) with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1.0 g·l−1 glucose, Earle's Balanced Salt Solution containing 1.5 g·l−1 sodium bicarbonate and supplemented with 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate and 10% foetal bovine serum. MDCK-MDR1 cells (passages 8–15) were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum containing 80 ng·ml−1 colchicine for selected growth of transfected cells (Pastan et al., 1988). Non-transfected MDCK cells (Type I) (passages 25–30) were cultured under the same conditions without the addition of colchicine. MRP-1 overexpressing L-MRP1 cells (passages 4–6) as well as the wildtype cells LLC-PK1 (passages 35–38) were grown in medium-199 containing Earle's salt, 2 mM L-glutamine and 2.2 mg·l−1 sodium bicarbonate and supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum as well as 100 u·ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg·ml−1 streptomycin. MRP-2 overexpressing MDCK-II-MRP2 cells (passages 4–6) as well as the wildtype cells MDCK-II (passages 75–79) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 100 u·ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg·ml−1 streptomycin.

For transport experiments, cells were grown as epithelial monolayers on polycarbonate membrane inserts (4.2 cm2 growth area with a density of 2.0–2.5·105 cells cm−2 and a mean pore diameter of 0.4 μm) in 6-well plates. Cell confluence and monolayer integrity was verified by microscopy and determination of transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) using a Millipore Millicell-ERS system fitted with ‘chopstick' electrodes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). Cell monolayers (4.2 cm2) were used when the (absolute) TEER had reached values between 400–500 (Caco-2), 250–300 (MDCK-I), 130–150 (MDCK-II), 150–180 (LLC-PK1), 1500–2000 (MDCK-MDR1), 600–700 (L-MRP1) or 150–200 (MDCK-II-MRP2) Ω. Cell-free membrane inserts (4.2 cm2) had TEER values of 120 Ω.

Bidirectional transepithelial transport studies

Transport studies were carried out 5 days after seeding LLC-PK1/L-MRP1 and MDCK-II/MDCK-II-MRP2, 7 days after seeding MDCK-I/-MDR1 and 21 days after seeding Caco-2 cells. In all cases, the media was renewed within 24 h prior to testing. The experimental procedure was adapted from Hunter et al. (1993c) and Cavet et al. (1996) with slight modifications. Briefly, cell monolayers were washed once and preincubated with Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 1.0 g·l−1 glucose and supplemented with 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37°C in a humidified CO2-atmosphere. Then, fresh prewarmed HBSS-HEPES containing 1% of either losartan or EXP 3174 stock solution (in acetonitrile/water 50%/50% v v−1) was added to either the apical (1.5 ml) or the basal (2.5 ml) side of the cell monolayer, while drug-free HBSS-HEPES was placed on the opposite side. The final organic solvent concentration in HBSS-HEPES was always kept below 1%, a concentration, which did not alter cell viability or permeability. In parallel experiments, the hydrophilic paracellular marker molecule [14C]-mannitol (0.1 μC ml−1, 6.4 μM) was added to verify monolayer integrity during exposure to losartan or EXP 3174.

Cell cultures were then incubated in a shaking incubator (Fisher Scientific Inc., Santa Clara, CA, U.S.A.) at 37°C. After 0.5, 1, 2 and 3 h, unless indicated otherwise, 250 μl-samples were taken from the apical (to study basal-to-apical transport) or the basal (to study apical-to-basal transport) side. The same volume of fresh pre-warmed HBSS-HEPES was added to keep the volume constant. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis by high performance-liquid chromatography–electrospray mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS) (see below). Cumulative transport was calculated after correction for dilution, and accounting for volume differences in the apical and basolateral compartments. Net secretion was defined as the ratio of basolateral-to-apical over apical-to-basolateral transport.

Temperature-dependency of transepithelial transport

To test for temperature-dependency, transport across MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cells incubated at 4°C and 37°C were compared.

‘Uphill' transport

As mentioned above, in the standard set up, the study drugs were added to one side of the cell monolayers, and concentrations were measured in the other compartment. The ability to translocate drugs across membranes or cell monolayers against a concentration gradient is an indicator for the involvement of active transport processes.

To evaluate as to whether active transport is involved in losartan and EXP 3174 transport and to eliminate a potential concentration gradient-driven contribution to their transport, equal concentrations (10 nM) of losartan or EXP 3174 were added to both the apical and basal sides of MDCK-MDR1 or Caco-2 cells. In contrast to the standard set up, transport from one side of the cell monolayer to the other would require transport against a concentration gradient.

After 2 h of incubation, samples from both the apical and basal compartments were taken and drug concentrations were measured.

Energy-dependency of transepithelial transport

To evaluate whether losartan and EXP 3174 transport was energy-dependent, MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cells were pre-incubated for 10 min with 1 mM 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP), a metabolic inhibitor, on both the apical and basal side, before losartan or EXP 3174 were added to either the apical or basolateral compartment.

Inhibition studies

Ten μM cyclosporine or 25 μM vinblastine, at these concentrations well-known inhibitors of P-glycoprotein and MRP (Ford & Hait, 1990), were added to both the apical and basal side of MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cells.

Determination of Michaelis-Menten constant (KM) and maximum velocity (Vmax) of losartan and EXP 3174 transport

The transport of losartan (0.010–1.5 mM) from the apical-to-basal and basal-to-apical sides of both the Caco-2 and MDCK-MDR1 cell monolayers was followed for 3 h, with sampling after 0.5, 1, 2 and 3 h. To determine the apparent Km and Vmax of P-glycoprotein-dependent transport of losartan in MDCK-MDR1 cells, cell cultures were incubated with 10, 20, 40, 80, 100, 125, 250, 500, 750, 1000 and 1500 μM of losartan (n=6). Caco-2 cells were incubated with the following losartan concentrations: 10, 20, 40, 80, 100, 125, 250, 500 and 750 μM (n= 6) and the following EXP 3174 concentrations: 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 μM (n=6). Data were fitted for each individual curve and the apparent KM and Vmax values were calculated using the SigmaPlot software (version 5.0, Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA, U.S.A.).

Determination of intracellular metabolite formation of losartan

Following bidirectional transport studies, the cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with 1N-sodium hydroxide/sodium dodecylsulphate 0.1%. The supernatant was analysed for monohydroxy-metabolites of losartan, for EXP 3174 as well as for glucuronides of losartan and EXP 3174.

LC/LC-MS analysis

Samples were analysed on a Hewlett-Packard LC/LC-MS system (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.). The LC-system for sample extraction consisted of a Perkin-Elmer LC-250 binary pump and a HP1090 autosampler. Samples were analysed on a HP1090 HPLC-system (Hewlett-Packard, Palo-Alto, CA, U.S.A.), which was connected to the extraction HPLC-system using a 6-port Rheodyne switching valve (Rheodyne, Cotati, CA, U.S.A.). The 59987A electrospray interface was equipped with an Iris Hexapole Ion Guide (Analytica of Branford, Branford, CT, U.S.A.) and connected to a 5989B mass spectrometer. The LC/LC-MS system was controlled and data were processed using ChemStation software revision A04.02 for the HPLC system and C.03.00 for the electrospray interface and mass spectrometer (all Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.). Unprocessed samples were directly injected into the extraction LC-system and loaded onto a 30·4.6 mm Capcell PAK™ UG120CN column (Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan). The analytes were washed and concentrated on the extraction column using an isocratic acetonitrile/0.025% formic acid (1/ 9 v v−1) mobile phase. The flow rate was 1.0 ml min−1. After 3 min, the column switching valve was activated, the extraction column back-flushed and the analytes eluted from the extraction column by the analytical HPLC system onto a 150·2 mm CAPCELL PAK™ UG120 CN (Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan) analytical column. A linear acetonitrile/0.025% formic acid gradient (20–60% acetonitrile in 10 min) was used with a flow rate of 0.25 ml min−1. The mass spectrometer was run in the negative, selected ion mode. The mass spectrometer was focused on the following ions with a dwell time of 500 ms: Losartan m/z=421 and EXP 3174 m/z=435. The compounds were quantified using an external calibration curve. All methods were validated prior to study sample analysis and quality control and calibration samples were run during study sample analysis to control validity of the results. The recovery was better than 95% and the lower limit of quantitation of all compounds was 0.5 μg l−1. During validation and study sample analysis, linearity was always better than r2=0.99 and inter-assay variability <15%.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean±s.d. Student's two-tailed t-test was used to test the significance of the difference between mean values (SPSS, Version 9.0, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Transepithelial transport of losartan in MDCK-I, MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cells

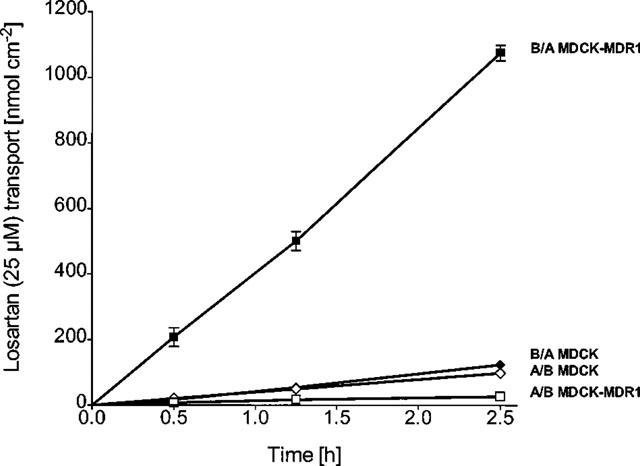

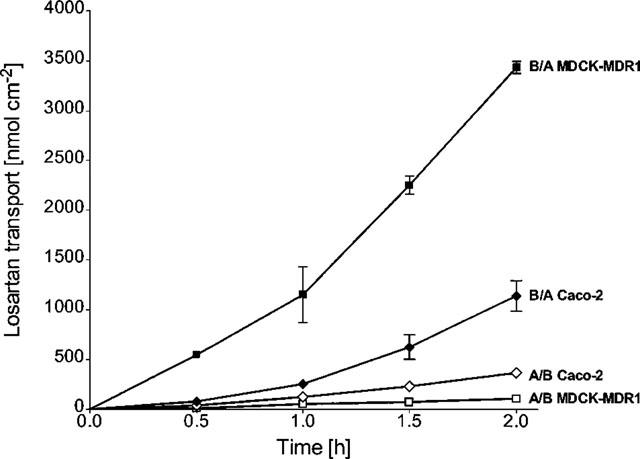

The secretory basolateral-to-apical (B/A) flux of 20 μM losartan across MDCK-MDR1 cell monolayers was significantly greater than its absorptive apical-to-basolateral (A/B) flux (ratio=31±1, n=6). In contrast, the B/A and A/B fluxes in non-transfected MDCK-I cells (control) did not differ significantly (Figure 2). In Caco-2 cells, the B/A flux of losartan was 35% lower than in MDCK-MDR1 cells (n=6), while the A/B flux was 2.5 fold greater resulting in a B/A to A/B ratio of 4±1 (n= 6) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Bidirectional transepithelial transport of 20 μM losartan across (non-transfected) MDCK-I and MDCK-MDR1 cells. B/A basolateral-to-apical, A/B apical-to-basolateral transport. Values are means±s.d., n=6.

Figure 3.

Bidirectional transepithelial transport of 40 μM losartan across MDCK-MDR1 cell, monolayers in comparison to Caco-2 cells. B/A basolateral-to-apical, A/B apical-to-basolateral transport. Values are means±s.d., n=6.

Transepithelial transport of EXP 3174 in Caco-2 and MDCK-MDR1 cells

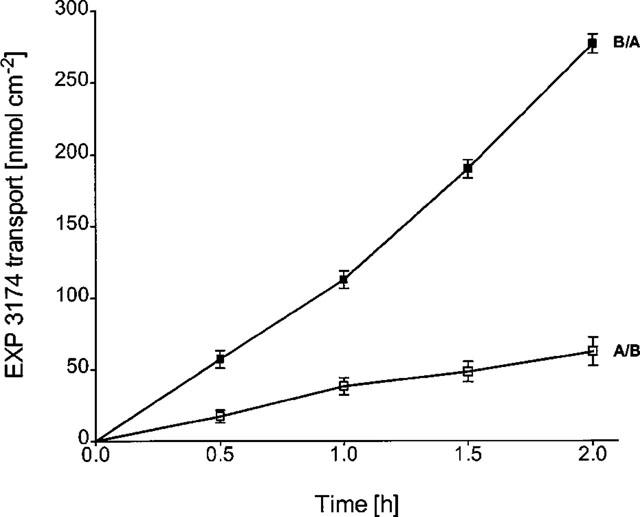

The basolateral-to-apical (B/A) flux of 10–150 μM EXP 3174 across MDCK-MDR1 cell monolayers was not significantly greater than its apical-to-basolateral (A/B) flux, indicating that the metabolite was not secreted in the P-glycoprotein-overexpressing cell line (7.2–115.6 nmol·cm−2·h−1 for B/A and 6.7–76.5 nmol·cm−2·h−1 for A/B with an apparent permeability coefficient Papp=2.7·10−7 cm·s−1). In contrast, in Caco-2 cells, a significantly higher secretory (B/A) than absorptive (A/B) transport of EXP 3174 (25 μM) was observed resulting in a B/A-to-A/B ratio of 5±1, n=6 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bidirectional transepithelial transport of 25 μM EXP 3174 across Caco-2 cell monolayers. B/A basolateral-to-apical, A/B apical-to-basolateral transport. Values are means±s.d., n=6.

Time-dependency of losartan and EXP 3174 transport

With both losartan and EXP 3174, a concentration-dependent increase in flux following incubation times longer than 1 h was observed in MDCK-MDR1 (losartan, Figure 3) as well as Caco-2 cells (losartan, Figure 3; EXP 3174, Figure 4).

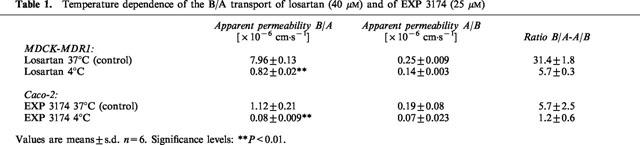

Temperature-dependency of losartan and EXP 3174 transport

The temperature-dependency of the specific basolateral-to-apical transport of losartan and EXP 3174, as a characteristic of carrier-mediated transport, was tested in MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cells, respectively. In both cases, the B/A fluxes were significantly reduced at 4°C, yielding a ratio of B/A flux at 37°C to that at 4°C of 10±0.5 (n=6) for losartan and 14±3 (n=6) for EXP 3174 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Temperature dependence of the B/A transport of losartan (40 μM) and of EXP 3174 (25 μM)

‘Uphill' transport of losartan and EXP 3174

After 2 h of incubation, significantly more drug was found on the apical side, suggesting that transport of both compounds was mediated against a concentration gradient (apical 55.7±3% versus basal 36.5±1.5% for losartan in MDCK-MDR1 epithelia, 64±2% versus 32.7±2.5% for EXP 3174 in Caco-2 epithelia, n=6, both P<0.05, per cent of total amount of drug).

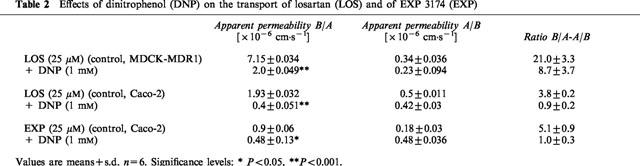

Energy-dependency of losartan and EXP 3174 transport

In presence of the metabolic inhibitor DNP, the B/A fluxes of both losartan (in MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2) and EXP 3174 (Caco-2) were significantly decreased. While in MDCK-MDR1 cells the losartan B/A flux was still greater than the flux in the A/B direction, in Caco-2 cells the B/A and A/B fluxes of losartan and EXP 3174 resulted in a 1 : 1 ratio, indicating purely passive diffusion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of dinitrophenol (DNP) on the transport of losartan (LOS) and of EXP 3174 (EXP)

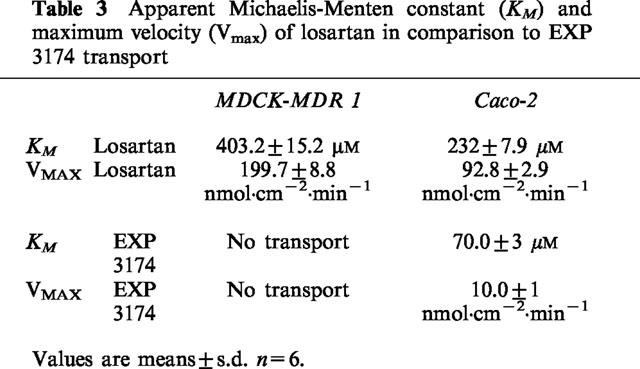

Michaelis-Menten constants (KM) and maximum velocities (Vmax) of losartan transport

The B/A flux of losartan in both MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cell monolayers was concentration dependent and saturable, and followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics. In MDCK-MDR1 cells, the apparent permeability constant PappA-B for the A/B flux (absorptive direction) was 2.3·10−7 cm·s−1, in Caco-2 cells, 7.6·10−7 cm·s−1 (Table 3). Monolayer (4.2 cm2) integrity was verified by (i) consistently high transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) values (Caco-2: 400-500 Ω; MDCK-MDR1: 1500–2000 Ω) across the cell monolayers before and after the study, and (ii) a passive, paracellular diffusion of [14C]-mannitol of less than 1.0% h−1 in the apical-to-basolateral as well as the basolateral-to-apical direction.

Table 3.

Apparent Michaelis-Menten constant (KM) and maximum velocity (Vmax) of losartan in comparison to EXP 3174 transport

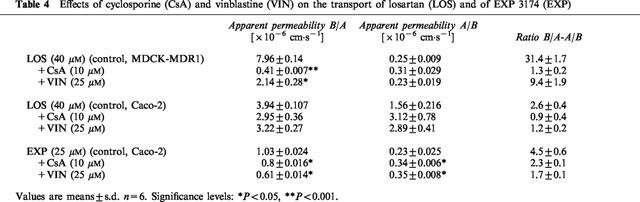

Inhibition of transepithelial transport of losartan

After the addition of cyclosporine or vinblastine to both the apical and basolateral compartments of MDCK-MDR1 cell cultures, the B/A transport of 40 μM losartan across the monolayers was completely blocked in the presence of 10 M cyclosporine, and significantly inhibited in the presence of 25 μM vinblastine (25% of control, P<0.05) without affecting the A/B flux. In Caco-2 cells, the ratio of B/A-to-A/B transport of 40 μM losartan (ratio =2.6±0.4, n=6) was decreased more than 50% in the presence of both cyclosporine (ratio=0.9±0.4, n=6) and vinblastine (ratio=1.2±0.2, n=6) by decreasing B/A transport and increasing A/B transport of losartan (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of cyclosporine (CsA) and vinblastine (VIN) on the transport of losartan (LOS) and of EXP 3174 (EXP)

Apparent Michaelis-Menten constant (KM) and maximum velocity (Vmax) of EXP 3174 transport

The B/A flux of EXP 3174 across Caco-2 cell monolayers was concentration dependent and saturable, also following Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The apparent permeability constant PappA-B for the A/B flux (absorptive direction) was 1.8·10−7 cm·s−1 (n=6) (Table 3).

Inhibition of transepithelial transport of EXP 3174

Ten μM cyclosporine reduced the ratio of B/A-to-A/B transport of 25 μM EXP 3174 (ratio without cyclosporine=4.5±0.6, n=6) by 50% (ratio with cyclosporine=2.3±0.1, n=6). In the presence of 25 μM vinblastine the B/A-to-A/B ratio was decreased by 60% (ratio=1.7±0.1, n=6), which was caused by both a reduction of B/A transport and an increase of A/B transport of EXP 3174 (Table 4).

Intracellular metabolite formation of losartan and EXP 3174 in Caco-2 and MDCK-MDR1 cells

Following bidirectional transport studies and verification of integrity of the cell monolayers, Caco-2 as well as MDCK-MDR1 cells were analysed for intracellular metabolite formation of losartan and EXP 3174 and potential metabolite accumulation. Apart from a negligible percentage (less than 0.02%) of losartan that was converted to EXP 3174, no other metabolites such as glucuronides of losartan and/or of EXP 3174 were found.

Lack of transepithelial transport of both losartan and EXP 3174 in MRP-1- as well as MRP-2-overexpressing cell systems in comparison to wildtype cells

Polarized expression of MRP-1 (in L-MRP1 cells) as well as of MRP-2 (in MDCK-II-MRP2 cells) was checked by control experiments using standard substrates such as [3H]-vincristine in the presence of 5 mM GSH for MRP1 and [3H]-vinblastine for MRP-2 (Evers et al., 1998; Renes et al., 1999). In comparison to wildtype LLC-PK1 cells, a 2 fold higher ratio of apical-to-basolateral over basolateral-to-apical transport of [3H]-vincristine was observed in the L-MRP1 cells. As already reported in the literature (Renes et al., 1999), [3H]-vincristine transport only took place in the presence of 5 mM GSH. Compared with MDCK-II wildtype cells, basolateral-to-apical transport of [3H]-vinblastine significantly increased from 26.0±2.7 fold (due to the activity of endogenous canine P-glycoprotein) to 38.1±3.1 fold in MDCK-II-MRP2 cells, indicating polarized expression of MRP2.

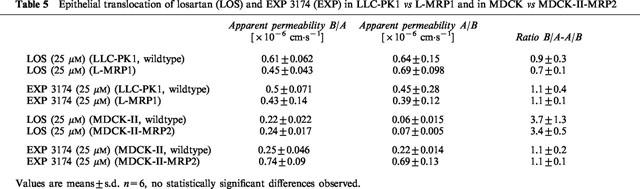

The extent and ratio of losartan translocation in polarized epithelial LLC-PK1 wildtype cells, which showed only passive diffusion, did not markedly differ from the extent and ratio in L-MRP1 cells. These are stably transfected with MRP-1 cDNA, localized in the basolateral plasma membrane, and therefore preferentially export MRP-1 substrates from the apical towards the basolateral side. Although in the L-MRP1 cells slightly more losartan appeared to be transported to the basolateral than to the apical side, the overall lack of net secretion of losartan in the L-MRP1 cells indicated that MRP-1 was unlikely to be involved in losartan transport (Table 5). Similarly, EXP 3174 passed through the monolayer in a passive fashion without any differences between LLC-PK1 and L-MRP1 cells (Table 5).

Table 5.

Epithelial translocation of losartan (LOS) and EXP 3174 (EXP) in LLC-PK1 vs L-MRP1 and in MDCK vs MDCK-II-MRP2

In MDCK-II wildtype cells, which, unlike LLC-PK1, express low levels of canine P-glycoprotein, a 3 fold net secretion of losartan due to endogenous P-glycoprotein in these cells was observed. In MRP-2-overexpressing MDCK-II-MRP2 cells, the amount of losartan transported was higher in comparison to wildtype cells, however, the resulting net secretion (3 fold) was unchanged in the presence of high MRP-2 concentrations (Table 5). Results with EXP 3174 also did not show differences in net secretion between wildtype MDCK-II and MDCK-II-MRP2 cells (Table 5).

Discussion

Our results indicate that both the parent drug losartan and its main active metabolite EXP 3174 are substrates for active efflux systems present in Caco-2 cells. This conclusion is based on the observations that transport of both compounds was temperature-dependent (Table 1), indicating carrier-mediated transport, was mediated against a concentration gradient and was inhibited in case of ATP-depletion due to the metabolic inhibitor DNP (Table 2). However, in contrast to its metabolite, the intestinal transport of losartan was mediated by P-glycoprotein as well as by other unidentified intestinal transporters present in Caco-2 cells, as demonstrated by a distinct losartan net secretion in the P-glycoprotein-overexpressing cell line MDCK-MDR1, while no directional transport was observed for EXP 3174 (Table 3). Losartan transport exhibited saturable Michaelis-Menten kinetics in MDCK-MDR1 as well as Caco-2 cells. In the P-glycoprotein-overexpressing cell line, the apparent KM was 74% higher than in Caco-2 cells.

While the saturable losartan transport in MDCK-MDR1 cells could mainly be attributed to P-glycoprotein, the lower KM in Caco-2 cells suggested that, in addition to P-glycoprotein, one or more other intestinal transporters significantly contributed to the active losartan transport. The apparent VMAX of losartan transport was higher in MDCK-MDR1 than in Caco-2 cells, which can be explained by the up to 10 fold higher concentrations of P-glycoprotein in the MDCK-MDR1 cells, although functional increases in transport do not strictly parallel these ratios (Zhang & Benet, 1998). Although in native MDCK-I as well as MDCK-II cells expression of P-glycoprotein activity was demonstrated by means of transepithelial vinblastine secretion (Hunter et al., 1993b), active transport of losartan was observed only in MDCK-II, not in MDCK-I cells. EXP 3174 lacked active transport in the P-glycoprotein-overexpressing MDCK-MDR1 cells, indicating that the carboxylic acid EXP 3174, in contrast to losartan, was not a P-glycoprotein substrate. This may be explained by the preference of P-glycoprotein for cationic to neutral substrates (Lang et al., 1997; Prueksaritanont et al., 1998). In Caco-2 cells, however, the metabolite EXP 3174 was transported with an apparent KM, which was less than one-third of the KM of losartan (Table 3).

Although within the linear concentration range, both losartan and EXP 3174 exhibited a time-dependent increase in basolateral-to-apical transport after incubation times of longer than 1 h. Since intracellular metabolism and increased permeability of the cell monolayers were excluded, the reason remained unclear.

To further characterize and identify the unknown transporters in Caco-2 cells, we studied the inhibition of the active transport of both losartan and EXP 3174 with cyclosporine and vinblastine, which represent well-known substrates/inhibitors of ABC transporters, in particular of P-glycoprotein and members of the MRP family (Evers et al., 1996; 1998; Ford & Hait, 1990; Germann et al., 1997; Kim et al., 1995; Liu et al., 1996; Nies et al., 1998). The inhibition was in neither case complete, implying that active transport of losartan as well as of EXP 3174 was mediated by two groups of intestinal transporters, one group which was inhibited and another which was not inhibited by cyclosporine or vinblastine. To assess the potential involvement of known MRP transporters, we evaluated a potential role of MRP-1 and MRP-2. Although as of today, six members of the MRP family have been identified, only MRP-1 and MRP-2 have successfully been expressed in cell lines in a way that the transporters are polarized and, thus, are suitable for transport studies (Borst et al., 1997; Evers et al., 1996; 1998). Our results suggest that neither MRP-1 or MRP-2 seem to play a significant role in the active transport of losartan or of its metabolite EXP 3174. Active transport by a route other than P-glycoprotein and which is not MRP1 or MRP2 has also been suggested for ciprofloxacin secretion (Cavet et al., 1997).

It is well established that Caco-2 cells undergo enterocyte-like differentiation and polarization resembling the small intestinal epithelium with expression of microvilli, brush-border membrane-associated enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase, and various transporters, among which P-glycoprotein (Hunter et al., 1993a; Pinto et al., 1983), members of the multidrug resistance-associated protein family (MRP) (Makhey et al., 1998; Norris et al., 1997) and the lung resistance protein (LRP) (Makhey et al., 1998) are most prominent. Since Caco-2 cells are a human cell line and express a large variety of intestinal transporters, it is generally believed that they better reflect the in vivo situation than cell systems overexpressing specific transporters and, therefore, allow for a better assessment of intestinal transport.

Our results showed that losartan is actively transported by P-glycoprotein, and it can therefore be anticipated that losartan undergoes considerable intestinal counter-transport in vivo. Since cytochrome P450-3A is the major cytochrome P450 enzyme in the small intestine (Kolars et al., 1994), it is reasonable to expect that losartan is converted to a significant extent to its metabolite EXP 3174 in the small intestinal mucosa, which is then actively transported through the apical membrane back into the gut lumen.

As recently reviewed by Lin et al. (1999), intestinal CYP3A-mediated metabolism is not sufficient to explain the low and variable oral bioavailability of most CYP3A-substrates. The most important, only partially resolved issue is the interaction between intestinal drug metabolism and counter-transport. Counter-transport presumably limits the access of drugs to the CYP enzymes and prevents CYP enzymes from being overwhelmed by the high drug concentrations in the intestine. In addition, with a drug being repeatedly transported out of the mucosa cells and being reabsorbed, repeated exposure may lead to more efficient metabolism (Benet et al., 1996; Gan et al., 1996). Therefore, counter-transport most likely plays an important role in intestinal drug metabolism by keeping the intra-mucosal drug concentrations in the linear range of CYP-enzymes.

As demonstrated in our study, the proteins involved in the transport of the more polar metabolite are different from those involved in the transport of losartan and have a higher affinity to the metabolite in comparison to losartan and its transporters. From a physiological point of view, the ABC-transporter/cytochrome P450-3A intestinal barrier becomes more efficient when drugs that have passed the first line of defense, namely the transporters, are converted to metabolites that are substrates of other transporters than the parent in order to avoid competitive interaction. The results are consistent with previous studies from our group with the immunosuppressants and cytochrome P450-3A/P-glycoprotein substrates tacrolimus and sirolimus (Lampen et al., 1996; 1998). These studies showed that in the intestinal mucosa, in the Ussing chamber, tacrolimus and sirolimus were metabolized and that the metabolites were transported against a concentration gradient through the apical membrane into the lumen chamber.

We believe that transport of losartan and its main metabolite from the intestinal endothelial cell into the gut lumen significantly contributes to the low oral bioavailability of losartan (33%) providing a potential site of interaction with drugs which are known substrates and inhibitors of intestinal transporters (Benet et al., 1996; Wacher et al., 1995). According to Artursson & Karlsson (1991), who report a good correlation between oral drug absorption in humans and apparent drug permeability coefficients in Caco-2 cells, losartan's incomplete absorption (33%) correlates well with its apparent permeability coefficient of 7.6·10−7 cm·s−1 in Caco-2 cells.

In addition, our study suggests that there may be a functional interaction between cytochrome P450 3A-dependent metabolism and intestinal transport in a way, that losartan is converted to a metabolite which is a substrate for transporters different from those which are involved in the intestinal transport of losartan. It can be hypothesized, that inhibitors or inducers of proteins, which are involved in the active transport of the metabolite, may have an impact upon losartan pharmacokinetics, although losartan itself might not be a substrate of such transporters.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Merck Research Laboratories (Rahway, NJ, U.S.A.) for providing both losartan and its metabolite EXP 3174, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) for providing cyclosporine. This study was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bonn, Germany) grants So 397/1-1 to A. Soldner and Ch 95/6-2 to U. Christians.

Abbreviations

- A/B

apical-to-basolateral

- ABC

ATP binding cassette

- B/A

basolateral-to-apical

- CYP

cytochrome P450 enzymes

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- MDCK

Madin-Darby canine kidney cells

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- TEER

transepithelial electrical resistance

- vs

versus

References

- ARTURSSON P., KARLSSON J. Correlation between oral drug absorption in humans and apparent drug permeability coefficients in human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;175:880–885. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91647-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUNGST B.J. Novel formulation strategies for improving oral bioavailability of drugs with poor membrane permeation or presystemic metabolism. J. Pharm. Sci. 1993;82:979–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENET L.Z., WU C.-Y., HEBERT M.F., WACHER V.J. Intestinal drug metabolism and antitransport processes: a potential paradigm shift in oral drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 1996;39:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- BORST P., KOOL M., EVERS R. Do cMOAT (MRP2), other MRP homologues, and LRP play a role in MDR. Cancer Biol. 1997;8:205–213. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAVET M.E., WEST M., SIMMONS N.L. Transport and epithelial secretion of the cardiac glycoside, digoxin, by human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1389–1396. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAVET M.E., WEST M., SIMMONS N.L. Fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin) secretion by human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1567–1578. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEELEY R.G., COLE S.P.C. Function, evolution and structure of multidrug resistance protein (MRP) Cancer Biol. 1997;8:193–204. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVERS R., KOOL M., VAN DEEMTER L., JANSSEN H., CALAFAT J., OOMEN L.C.J.M., PAULUSMA C.C., OUDE ELFERINK R.P.J., BAAS F., SCHINKEL A.H., BORST P. Drug export activity of the human canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in polarized kidney MDCK cells expressing cMOAT (MRP2) cDNA. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1310–1319. doi: 10.1172/JCI119886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVERS R., ZAMAN G.J.R., VAN DEEMTER L., JANSEN H., CALAFAT J., OOMEN L.C.J.M., OUDE ELFERINK R.P.J., BORST P., SCHINKEL A.H. Basolateral localization and export activity of the human multidrug resistance-associated protein in polarized pig kidney cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:1211–1218. doi: 10.1172/JCI118535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORD J.M., HAIT W.N. Pharmacology of drugs that alter multidrug resistance in cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 1990;42:155–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAN L.S., MOSELEY M.A., KHOSLA B., AUGUSTIJNS P.F., BRADSHAW T.P., HENDREN R.W., THAKKER D.R. CYP3A-like cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism and polarized efflux of cyclosporin A in Caco-2 cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1996;24:344–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERMANN U.A., FORD P.J., SHLYAKHTER D., MASON V.S., HARDING M.W. Chemosensitization and drug accumulation effects of VX-710, verapamil, cyclosporin A, MS-209 and GF120918 in multidrug resistant HL60/ADR cells expressing the multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP. Anti Cancer Drugs. 1997;8:141–155. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199702000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER J., HIRST B.H., SIMMONS N.L. Drug absorption limited by P-glycoprotein-mediated secretory drug transport in human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cell layers. Pharm. Res. 1993a;10:743–749. doi: 10.1023/a:1018972102702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER J., HIRST B.H., SIMMONS N.L. Transepithelial secretion, cellular accumulation and cytotoxicity of vinblastine in defined MDCK cell strains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993b;1179:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER J., JEPSON M.A., TSURUO T., SIMMONS N., HIRST B.H. Functional expression of P-glycoprotein in apical membranes of human intestinal Caco-2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1993c;268:14991–14997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM W.J., KAKEHI Y., HIRAI M., ARAO S., HIAI H., FUKUMOTO M., YOSHIDA O. Multidrug resistance-associated protein-mediated multidrug resistance modulated by cyclosporin A in a human bladder cancer cell line. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1995;86:969–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb03009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLARS J.C., LOWN K.S., SCHMIEDLIN R.P., GHOSH M., FANG C., WRIGHTON S.A., MERION R.M., WATKINS P.B. CYP3A gene expression in human gut epithelium. Pharmacogenetics. 1994;4:247–259. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMPEN A., CHRISTIANS U., GONSCHIOR A.K., BADER A., HACKBARTH I., VON ENGELHARDT W., SEWING K.F. Metabolism of the macrolide immunosuppressant tacrolimus by the pig mucosa in the Ussing chamber. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1730–1734. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMPEN A., ZHANG Y., HACKBARTH I., BENET L.Z., SEWING K.F., CHRISTIANS U. Metabolism and transport of the macrolide immunosuppressant sirolimus in the small intestine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;285:1104–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANG V.B., LANGGUTH P., OTTIGER C., WUNDERLI-ALLENSPACH H., ROGNAN D., ROTHEN-RUTISHAUSER B., PERRIARD J.C., LANG S., BIBER J., MERKLE H.P. Structure-permeation relations of Met-enkephalin peptide analogues on absorption and secretion mechanisms in Caco-2 monolayers. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997;86:846–853. doi: 10.1021/js960387x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN J.H., CHIBA M., BAILLIE T.A. Is the role of the small intestine in first-pass metabolism overemphasized. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:135–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU Y., HUANG L., HOFFMAN T., GOSLAND M., VORE M. MDR1 substrates-modulators protect against β-estradiol-17-β-D-glucuronide cholestasis in rat liver. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4992–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LO M.-W., GOLDBERG M.R., MCCREA J.B., LU H., FURTEK C.I., BJORNSSON T.D. Pharmacokinetics of losartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, and its active metabolite EXP 3174 in humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;58:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAKHEY V.D., GUO A., NORRIS D.A., HU P., YAN J., SINKO P.J. Characterization of the regional intestinal kinetics of drug efflux in rat and human intestine and in Caco-2 cells. Pharm. Res. 1998;15:1160–1167. doi: 10.1023/a:1011971303880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIES A.T., CANTZ T., BROM M., LEIER I., KEPPLER D. Expression of the apical conjugate export pump, Mrp2, in the polarized hepatoma cell line, WIF-B. Hepatology. 1998;28:1332–1340. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORRIS D.A., GUO A., MAKHEY V.D., SINKO P.J. Functional expression and immunoquantitation of multidrug resistance (MDR) efflux pumps, Pgp and MRP, in Caco-2 cells as a function of passage number. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:S669–S670. [Google Scholar]

- PASTAN I., GOTTESMAN M.M., UEDA K., LOVELACE E., RUTHERFORD A.V., WILLINGHAM M.C. A retrovirus carrying an MDR1 cDNA confers multidrug resistance and polarized expression of P-glycoprotein in MDCK cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:4486–4490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PINTO M., ROBINE-LEON S., APPAY M.-D., KEDINGER M., TRIADOU N., DUSSAULX E., LACROIX B., SIMON-ASSMANN P., HAFFEN K., FOGH J., ZWEIBAUM A. Enterocyte-like differentiation and polarization of the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2 in culture. Biol. Cell. 1983;47:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- PRUEKSARITANONT T., DELUNA P., GORHAM L.M., MA B., COHN D., PANG J., XU X., LEUNG K., LIN J.H. In vitro and in vivo evaluations of intestinal barriers for the zwitterion L-767,679 and its carboxyl ester prodrug L-775,318. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1998;26:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RENES J., DE VRIES E.G.E., NIENHUIS E.F., JANSEN P.L.M., MÜLLER M. ATP- and glutathione-dependent transport of chemotherapeutic drugs by the multidrug resistance protein MRP1. Br. J. Pharm. 1999;126:681–688. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEARNS R.A., CHAKRAVARTY P.K., CHEN R., CHIU S.H.-L. Biotransformation of losartan to its active carboxylic acid metabolite in human liver microsomes: Role of cytochrome P4502C and 3A subfamily members. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1995;23:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEARNS R.A., MILLER R.R., DOSS G.A., CHAKRAVARTY P.K., ROSEGAY A., GATTO G.J., CHIU S.H.-L. The metabolism of DUP 753, a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist, by rat, monkey and human liver slices. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1992;20:281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIMMERMANS P.B.M.W.M., WONG P.C., CHIU A.T., HERBLIN W.F., BENFIELD P., CARINI D.J., LEE R.J., WEXLER R.R., SAYE J.A.M., SMITH R.D. Angiotensin II receptors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Pharmacol. Rev. 1993;45:205–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WACHER V.J., WU C.Y., BENET L.Z. Overlapping substrate specificities and tissue distribution of cytochrome P450 3A and P-glycoprotein: implications for drug delivery and activity in cancer chemotherapy. Mol. Carcinog. 1995;13:129–134. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940130302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WONG P.C., PRICE W.A., CHIU A.T., DUNCIA J.V., CARINI D.J., WEXLER R.R., JOHNSON A.L., TIMMERMANS P.B.M.W.M. Nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists. XI. Pharmacology of EXP 3174: an active metabolite of DUP 753, an orally active antihypertensive agent. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;255:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG Y., BENET L.Z. Characterization of P-glycoprotein mediated transport of K02, a novel vinylsulfone peptidomimetic cysteine protease inhibitor, across MDR1-MDCK and Caco-2 cell monolayers. Pharm. Res. 1998;15:1520–1524. doi: 10.1023/a:1011990730230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]