Abstract

The respiratory response to microinjection of capsaicin and tachykinin receptor agonists into the commissural nucleus of the solitary tract (cNTS) was investigated in adult, urethane-anaesthetized rats which had been pretreated with capsaicin (50 mg kg−1 s.c.) or vehicle (10% Tween 80, 10% ethanol in saline) as day 2 neonates.

Microinjection of capsaicin (1 nmol) into the cNTS of vehicle-pretreated rats, significantly reduced respiratory frequency (59 breaths min−1, preinjection control, 106 breaths min−1) without affecting tidal volume (VT). In capsaicin-pretreated rats, the capsaicin-induced bradypnoea was markedly attenuated (minimum frequency, 88 breaths min−1; control, 106 breaths min−1).

In vehicle-pretreated rats, microinjection of substance P (SP, 33 pmol), neurokinin A (NKA, 33 pmol) and NKB (330 pmol), and the selective NK1 tachykinin receptor agonists, [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP (33 pmol) and septide (10 pmol), increased VT (maxima, 3.60–3.93 ml kg−1) compared with preinjection control (2.82 ml kg−1), without affecting frequency. The selective NK3 agonist senktide (10 pmol) also increased VT (3.93 ml kg−1) which was accompanied by a bradypnoea (−25 breaths min−1). The selective NK2 agonist, [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) (330 pmol) increased VT slightly but significantly decreased frequency (−12 breaths min−1). In capsaicin-pretreated rats, VT responses to SP and [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP were increased whereas the response to septide was abolished. Both the VT and bradypnoeic responses to senktide and [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) were significantly enhanced.

These results show that neonatal capsaicin administration markedly reduces the respiratory response to microinjection of capsaicin into the cNTS. The destruction of capsaicin-sensitive afferents appears to sensitize the NTS to SP, NKB, [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP, senktide and [Nle10]-NKA(4-10). Moreover, the loss of septide responsiveness in capsaicin-pretreated rats, suggests that ‘septide-sensitive' NK1 receptors may be located on the central terminals of afferent neurons.

Keywords: Tachykinins, capsaicin-pretreatment, nucleus of the solitary tract, respiration

Introduction

The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) is the primary integration site for many visceral reflexes and is rich in the tachykinins substance P (SP), neurokinin A (NKA) and NKB (Douglas et al., 1982; Kalia et al., 1984; Jordan & Spyer, 1986; Nagashima et al., 1989). Our recent functional studies employing SP, NKA and NKB, receptor-selective agonists and nonpeptide antagonists suggest that all three tachykinin receptors (NK1, NK2 and NK3) are present in the NTS and play a role in respiratory control at the brain stem level (Mazzone & Geraghty, 1999a; 2000). Microinjection of NK1 receptor agonists into the commissural NTS (cNTS) increases tidal volume (VT) whereas NK2 receptor agonists produce a bradypnoea (Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). NK3 receptor agonists cause a mixed response (increase VT and decrease frequency). Furthermore, tachykinin-induced increases in VT are attenuated by selective NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists (RP 67580 and SR 142801, respectively) but not by the NK2 receptor antagonist, SR 48968. However, the VT response to NKA is potentiated by SR 48968, suggesting that NK2 receptors in the NTS modify respiration.

The vanilloid capsaicin, releases neurotransmitters including calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), excitatory amino acids and tachykinins from the central and peripheral terminals of unmyelinated C-fibres and lightly myelinated Aδ-fibres which include peripheral chemoreceptor, baroreceptor and pulmonary afferents (Szolcsanyi, 1993). At the supraspinal level, vanilloid receptors (VR1) have been localized autoradiographically (using [3H]-resiniferatoxin binding) and immunocytochemically to discrete regions of the brain stem, namely the NTS, area postrema and parts of the spinal trigeminal nucleus (Szallasi et al., 1995; Tominaga et al., 1998; Guo et al., 1999). We have previously shown that microinjection of capsaicin into the cNTS produces a dose-dependent bradypnoea which is blocked by SR 48968 and SR 142801 but not by RP 67580 (Mazzone & Geraghty, 1999a). Thus, the capsaicin-induced respiratory slowing is at least partly mediated by the release of tachykinins and their subsequent stimulation of NK3 and possibly NK2 receptors.

Systemic administration of capsaicin to neonatal rats destroys the majority of C- and Aδ-fibres (Szolcsányi, 1993). The SP content of the NTS is markedly reduced in capsaicinized rats compared with vehicle-pretreated controls suggesting the loss of tachykinin-containing afferents (Helke & Eskay, 1985; Takano et al., 1988). Moreover, the respiratory response to hypoxia (increased ventilation) is reduced by 40% in adult rats pretreated with capsaicin as neonates (De Sanctis et al., 1991). The aim of the present study was to determine whether neonatal capsaicin pretreatment alters the adult respiratory response to microinjection of capsaicin and tachykinins into the cNTS.

Methods

Capsaicin pretreatment

All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Tasmania Ethics Committee (Animal Experimentation; project 98010). Neonatal (P2) Hooded Wistar rat pups were placed in an ice bath until neck muscle tone was lost. Pups were subsequently treated with 50 mg kg−1 s.c. capsaicin or vehicle (10% ethanol, 10% Tween 80 in normal saline) and revived under an infrared lamp. Both groups of rats were allowed to mature for 10 weeks and were of similar weight at the time of experimentation (vehicle-pretreated, 277±9 g, n=10; capsaicin-pretreated, 268±12 g, n=10).

Surgery

Mature vehicle- and capsaicin-pretreated rats were anaesthetized using urethane (0.5 g kg−1 i.p. and 0.5 g kg−1 s.c.) and prepared for microinjection studies as described previously by our laboratory (Mazzone & Geraghty, 1999a,1999b; 2000). Briefly, rats were mounted in a Kopf stereotaxic apparatus and the dorsal aspect of the brain stem was exposed by a craniotomy. Respiration, which was spontaneous and rhythmic, was recorded using subcutaneous electrodes and a calibrated impedance converter (UFI, Morro Bay, California, U.S.A.).

Injection of agents into the cNTS

For capsaicin injections, a glass micropipette was mounted in a micromanipulator and using obex as a reference point, the needle was inserted into the cNTS: AP −15 to −15.3 mm; L 0–0.3 mm relative to bregma and 0.4 mm into the dorsal surface of the brain stem (Paxinos & Watson, 1986). Capsaicin (1 nmol in 500 nl of 25% ethanol in normal saline) was then injected over 30 s into the cNTS (dose based on previous study; Mazzone & Geraghty, 1999a). Respiratory movements were recorded for 30 min following the injection.

Tachykinin peptides and analogues were injected using a microprocessor-controlled pump (UltraMicroPump II, World Precision Instruments) mounted on a micromanipulator. All peptides were injected in 100 nl over 30 s. Ten vehicle- and capsaicin-pretreated rats were injected with three-to-four of the following agents: SP (33 pmol), NKA (10 pmol), NKB (100 pmol), [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP (33 pmol), septide (1 pmol), senktide (1 pmol), [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) (330 pmol) and vehicle (25% ethanol in saline). Except for [Nle10]-NKA(4-10), which does not affect tidal volume (VT), doses were based on the approximate ED50 for increasing VT (Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). Experiments were paired (one vehicle- and one capsaicin-pretreated rat) and the order of injection of agents was randomized for the ten pairs of rats. Rats were allowed to recover for 70 min between injections.

At the end of each experiment, rats were killed with an overdose of pentobarbitone, the brain stems were removed and later sectioned and stained to ascertain the exact injection site. Prior to removal of the brain stem, a polyethylene tube attached to a 5 ml syringe was inserted into the trachea and the impedance converter was calibrated by graded inflation of the lung. Respiratory movements were measured over a 20 s time interval and then converted to frequency, VT and minute ventilation (VE). Volumes were subsequently normalized to body weight. Data obtained from animals which showed evidence of the needle tract in the cNTS were compared using the Student t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Drugs and materials

All tachykinin peptides and analogues (>95% purity) were purchased from Auspep (Melbourne, Australia). Capsaicin (>99% purity) was purchased from the Sigma Chemical Company. All agents for microinjection were dissolved in 25% ethanol in normal saline and stored in frozen aliquots. Other reagents were of analytical grade.

Results

Effect of neonatal capsaicin-pretreatment on the respiratory response to capsaicin

In adult rats, pretreated with vehicle as day 2 neonates, microinjection of capsaicin (1 nmol) into the cNTS significantly slowed respiration (59±3 breaths min−1 compared with pre-injection control, 106±1 breaths min−1; Figure 1a). VT was not altered by capsaicin and thus, VE followed a similar course to frequency (Figure 1b,c). Neonatal capsaicin-pretreatment did not affect baseline respiration but dramatically reduced the bradypnoeic response to capsaicin (minimum frequency, 88±9 breaths min−1).

Figure 1.

Respiratory response to microinjection of capsaicin (1 nmol) into the commissural nucleus of the solitary tract of urethane-anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing adult rats (10 weeks) pretreated as neonates (day 2) with capsaicin (50 mg kg−1 s.c.). (a) Tidal volume (VT), (b) respiratory frequency (f) and (c) minute ventilation (VE). Values are the mean of four animals and vertical bars show s.e.mean. Where error bars are not obvious, they are within the symbol.

Effect of neonatal capsaicin-pretreatment on the respiratory response to SP, NKA and NKB

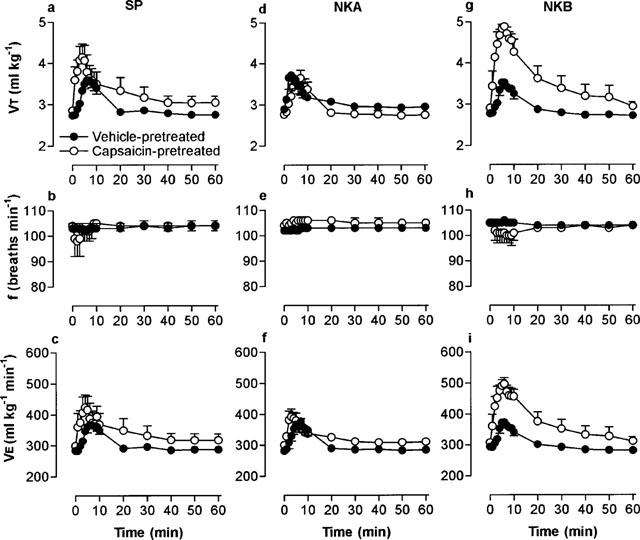

The respiratory response to microinjection of the peptide vehicle (100 nl, 25% ethanol in normal saline) was negligible in both vehicle- and capsaicin-pretreated rats (Table 1). Microinjection of SP (33 pmol), NKA (10 pmol) and NKB (100 pmol) into the cNTS of vehicle-pretreated rats produced a significant increase in VT, with only minimal effects on frequency (Figure 2; Table 1). Thus, the VE response to agonists essentially followed the same course as the VT response (Figure 2c,f,i). In capsaicin-pretreated rats, microinjection of SP into the cNTS produced a significantly (P<0.05) greater VT response between 1 and 4 min after injection, although the maximum response was only slightly larger (but not significant) compared to vehicle-pretreated controls (Figure 2a; Table 1). In contrast, the VT response to microinjection of NKA was unchanged (Figure 2d). The increase in VT following injection of NKB was significantly greater in capsaicin-pretreated rats compared to vehicle-pretreated controls (Figure 2g; Table 1). Capsaicin-pretreatment did not alter the frequency response to any of the agonists (Figure 2b,e,h).

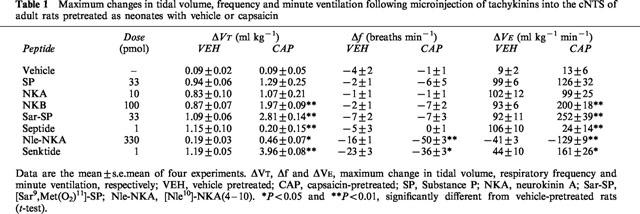

Table 1.

Maximum changes in tidal volume, frequency and minute ventilation following microinjection of tachykinins into the cNTS of adult rats pretreated as neonates with vehicle or capsaicin

Figure 2.

Respiratory response to microinjection of tachykinins into the commissural nucleus of the solitary tract of urethane-anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing adult rats (10 weeks) pretreated as neonates (day 2) with capsaicin (50 mg kg−1 s.c.). Doses injected were 33 pmol SP (a–c), 10 pmol NKA (d–f) and 100 pmol NKB (g–i). Tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (f) and minute ventilation (VE). Values are the mean of four animals and vertical bars show s.e.mean. Where error bars are not obvious, they are within the symbol.

Effect of neonatal capsaicin-pretreatment on the respiratory response to receptor-selective tachykinins

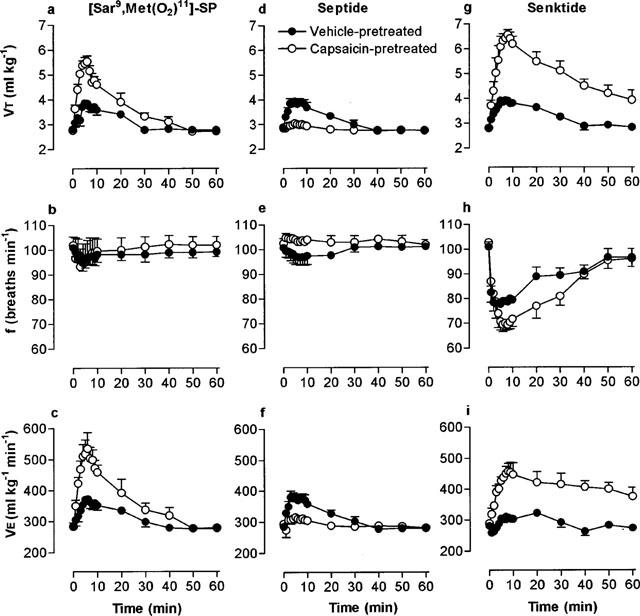

In vehicle-pretreated rats, microinjection of the selective NK1 agonists, [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP (33 pmol) and septide (1 pmol), increased VT without affecting frequency (Figure 3a,b,d,e). Hence, VE followed a similar course to VT (Figure 3c,f). In capsaicin-pretreated rats, the response to [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP was significantly (P<0.01) increased whereas the response to septide was markedly attenuated (Table 1). In the vehicle group, the NK3 agonist, senktide (1 pmol), increased VT and also decreased frequency (Figure 3g,h). Both the VT and frequency responses to senktide were significantly increased in capsaicin-pretreated rats. However, stimulation of VT predominated over the bradypnoea and thus, microinjection of senktide resulted in an overall increase in VE in both pretreatment groups (Figure 3i).

Figure 3.

Respiratory response to microinjection of NK1 and NK3 receptor-selective tachykinins into the commissural nucleus of the solitary tract of urethane-anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing adult rats (10 weeks) pretreated as neonates (day 2) with capsaicin (50 mg kg−1 s.c.). Doses injected were 33 pmol [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP (a–c), 10 pmol septide (d–f) and 10 pmol senktide (g–i). Tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (f) and minute ventilation (VE). Values are the mean of four animals and vertical bars show s.e.mean. Where error bars are not obvious, they are within the symbol.

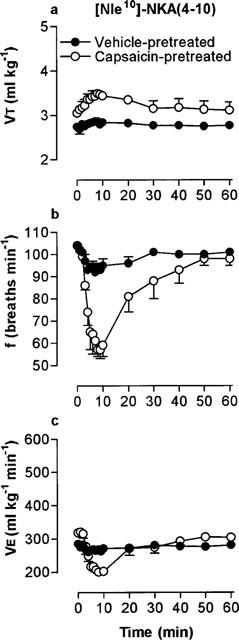

Microinjection of 330 pmol [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) produced a bradypnoea which was markedly and significantly enhanced in capsaicin-pretreated rats (Figure 4b). Interestingly, [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) had no effect on VT in vehicle-pretreated rats but significantly increased VT in the capsaicin-pretreated group (Figure 4a; Table 1).

Figure 4.

Respiratory response to microinjection of 300 pmol of the NK2 receptor-selective agonist, [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) into the commissural nucleus of the solitary tract of urethane-anaesthetized, spontaneously breathing adult rats (10 weeks) pretreated as neonates (day 2) with capsaicin (50 mg kg−1 s.c.). (a) Tidal volume (VT), (b) respiratory frequency and (c) minute ventilation (VE). Values are the mean of four animals and vertical bars show s.e.mean. Where error bars are not obvious, they are within the symbol.

Discussion

Our preceding study showed that all three tachykinin receptors (NK1, NK2 and NK3) are present in the NTS, and undoubtedly play a role in the central control of respiration (Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). The aim of the present study was to determine whether neonatal capsaicin administration, which destroys a large proportion of tachykinin-containing cardio-respiratory afferents, alters the respiratory actions of tachykinins in the NTS.

Effect of capsaicin-pretreatment on the respiratory response to capsaicin

We have previously shown that microinjection of the vanilloid capsaicin into the cNTS produces severe bradypnoea, which is mediated by tachykinin NK2 and NK3, but not NK1, receptors (Mazzone & Geraghty, 1999a). In the present study, this bradypnoeic response was almost abolished in adult rats which were pretreated systemically as neonates with capsaicin, but preserved in vehicle-pretreated animals.

The reduction in the sensitivity to capsaicin is indicative of a substantial loss of capsaicin-sensitive afferents in the NTS and surrounding regions. Szallasi et al. (1995) reported that neonatal capsaicin administration abolished [3H]-RTX binding in the NTS and other brain stem regions. In addition, the respiratory response to hypoxia is markedly attenuated in adult rats pretreated as neonates with capsaicin, indicating a disruption of the peripheral chemoreceptor reflex pathway (De Sanctis et al., 1991). Interestingly, we have also observed that capsaicin-induced bradypnoea is abolished in adult rats which were pretreated with capsaicin 14 days earlier, suggesting that adult-pretreatment can also disrupt afferent input to the NTS (Mazzone & Geraghty, unpublished observations). Thus, the present data provide evidence that the destruction of sensory neurons, and associated vanilloid binding sites (receptors) by neonatal capsaicin administration leads to a loss of respiratory response to central (NTS) administration of capsaicin.

Effect of capsaicin-pretreatment on the respiratory response to SP, [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP and septide

In the present study, the VT responses to the selective NK1 receptor agonist, [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP, and (to a lesser extent) SP were increased in capsaicin-pretreated rats suggesting a direct or indirect input of capsaicin-sensitive afferents to NK1 receptors in the NTS, although NK1 receptors appear not to be involved in the direct respiratory actions of capsaicin (Mazzone & Geraghty, 1999a). In contrast, Hedner & coworkers (1985) reported that neonatal capsaicin pretreatment increased the frequency (rather than VT) response to i.c.v. administration of SP (3 μg). The reasons for these conflicting observations are unclear, but probably reflect the different routes of drug administration and initial site(s) of action of SP in the CNS.

The exaggerated responsiveness to both [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP and SP may simply be explained by reduced enzymatic degradation (e.g., by neutral endopeptidase) in capsaicin-pretreated rats. However, this is unlikely since the peak change in VT induced by 33 pmol [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP (2.81 ml kg−1) in capsaicin-pretreated rats was greater than the maximum change induced by 10 fold higher dose in untreated rats (2.10 ml kg−1; Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). Thus, whereas 33 pmol [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP produced a half maximal response in untreated rats, the same dose yielded a supramaximal response in capsaicin-pretreated rats. The dramatic increase in the VT response to [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP in capsaicin-pretreated rats is more likely due to an increase in the number, or improved coupling, of postsynaptic NK1 receptors in the NTS. Chemical or surgical destruction of tachykinin-containing neurons, leads to an increase in the number of post-synaptic NK1 receptors (assessed using in vitro autoradiography) in the rat spinal cord (Mantyh & Hunt, 1985; Yashpal et al., 1991; Croul et al., 1995). However, studies addressing the effects of surgical denervation on tachykinin receptors in the brain stem have yielded conflicting data. For example, vagotomy (which leads to destruction of some baroreceptor, chemoreceptor and pulmonary afferents) has been reported to not change or decrease the number of SP binding sites (NK1 receptors) in the NTS (Helke et al., 1984; Manaker & Zucci, 1993). The present study suggests that chemical denervation (neonatal capsaicin-pretreatment) dramatically changes the responsiveness of the NTS to NK1 receptor agonists.

In contrast to SP and [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP, where respiratory responses were exaggerated, the VT response to another NK1 agonist, septide, was effectively absent in capsaicin-pretreated rats. There are several reports of ‘septide-sensitive' NK1 receptors in the CNS (Steinberg et al., 1995; Maubach & Jones, 1997). However, to date studies have failed to determine whether the actions of septide are due to an interaction with a site different from that of SP on the classical NK1 receptor, a NK1 receptor conformer, or with a distinct receptor protein.

If septide-sensitive and -insensitive receptors are present in the NTS, then the present data may indicate that the capsaicin-pretreatment changes the type or conformation of the NK1 receptor in the NTS in favour of the ‘septide-insensitive' form (Maggi & Schwartz, 1997). Although the mechanisms underlying this alteration are not known, capsaicin-pretreatment may change the expression of postsynaptic NK1 receptors in the NTS, such that there are fewer septide-sensitive binding sites present or exposed to the agonist. Alternatively, septide-sensitive NK1 receptors may be located presynaptically in the NTS. In support of this proposal, capsaicin-pretreatment abolished only the respiratory response to septide and capsaicin. Since capsaicin is presumed to act presynaptically, then the loss of response to both agents suggests a similar synaptic locus of action. Indeed, there is both functional and immunocytochemical evidence for presynaptic tachykinin receptors which regulate the release of tachykinins and other neurotransmitters in the rat NTS and striatum and from sympathetic preganglionic neurons (Tremblay et al., 1992; Cammack & Logan, 1996; Jakob & Goldman-Rakic, 1996; Bailey & Jones, 1999).

Different synaptic locations of septide-sensitive and insensitive receptors may explain why capsaicin-pretreatment exaggerated the VT response to [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP more than to SP. In vehicle-pretreated rats, the VT response to [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP is probably mediated solely by septide-insensitive (postsynaptic) receptors, whereas the response to SP may be due to activation of both septide-sensitive (presynaptic) and -insensitive NK1 receptors, although [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP and SP yield similar maxima. In support of this, point mutation of the NK1 receptor increases the affinity of septide (and NKA), without altering that of SP (Ciucci et al., 1998). Thus, deafferentation of the NTS by capsaicin pretreatment may upregulate septide-insensitive (postsynaptic) NK1 receptors, resulting in the enhanced responsiveness to [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP. In contrast, the response to SP would be reduced compared with that of [Sar9,Met(O2)11]-SP since, although capsaicin-pretreatment appears to upregulate septide-insensitive receptors, there appears to be a concomitant decline in septide-sensitive NK1 receptors.

Effect of capsaicin-pretreatment on the respiratory response to NKA and [Nle10]-NKA(4-10)

Microinjection of NKA into the NTS stimulates VT, a response which appears to be mediated by NK1 receptors since the actions of NKA are attenuated by the NK1 antagonist RP 67580 (Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). Furthermore, there is some evidence that NKA may act at septide-preferring NK1 receptors, since point mutation of the NK1 receptor increases binding affinity for both septide and NKA (Ciucci et al., 1998). However, respiratory responses elicited by NKA in capsaicin-pretreated rats were similar to that of vehicle-pretreated controls. The reason for this lack of change in responsiveness is unclear, since the respiratory response to septide is abolished in capsaicin-pretreated animals. One possibility is that whilst NKA may have higher affinity for septide-sensitive receptors, NKA may still interact with septide-insensitive receptors. Thus, although there appears to be a loss of septide-sensitive receptors in capsaicin-pretreated rats, a reduction in the VT response to NKA would be offset by the apparent sensitization (up-regulation) of septide-insensitive NK1 receptors.

The respiratory response to [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) is rather unique compared with all other tachykinins investigated. This selective NK2 receptor agonist induces a bradypnoea in untreated rats, without affecting VT, which is blocked by the nonpeptide antagonist SR 48968 (Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). In capsaicin-pretreated rats, the bradypnoeic response to [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) was markedly enhanced, suggesting sensitization or upregulation of NK2 receptors in the NTS. Interestingly, microinjection of [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) increased VT in capsaicin-pretreated rats, resulting in only minor reductions in VE. The mechanisms underlying the VT response are unclear, since injection of 1 nmol [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) into untreated rats produces a similar degree of respiratory slowing (approximately, −40 breaths min−1) without any effect on VT (Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). The increase in VT may simply reflect a mechanism to compensate for the marked reduction in VE which would result from the severe bradypnoea. Alternatively, the VT response may be due to an interaction between [Nle10]-NKA(4-10) and NK1 and/or NK3 receptors, which appear to be sensitized, or increased in number, by capsaicin-pretreatment.

To date localization studies have failed to detect NK2 receptors in the rat brain stem, although specific NK2 immunoreactivity has recently been observed in the spinal cord where previous studies had failed to detect the receptor (Zerari et al., 1998). We are currently attempting to localize and quantitate NK2 receptors in the NTS (particularly in capsaicin-pretreated rats) using immunocytochemistry and autoradiography. Indeed, if successful, up-regulating NK2 receptors by neonatal capsaicin-pretreatment may be a novel method of studying the pharmacology of central NK2 receptors.

Effect of capsaicin-pretreatment on the respiratory response to NKB and senktide

In the present study, capsaicin pretreatment dramatically enhanced both the frequency and VT response to NK3 receptor agonists. Moreover, the peak stimulation of VT by senktide (3.96 ml kg−1) was significantly greater than the previously observed maximum in untreated animals (2.20 ml kg−1; Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000). Thus, NK3 receptor-mediated respiratory responses also appear to be supersensitized by capsaicin-pretreatment. Again, receptor up-regulation may explain the enhanced responsiveness to NK3 agonists. Indeed, unilateral surgical deafferentation of L1-S2 spinal cord roots results in reactive up-regulation of dorsal horn NK3 receptors within 1 week of the surgery (Yashpal et al., 1991; Croul et al., 1995). However, the subsequent sensitivity of spinal cord neurons to NK3 agonists was not determined.

Although NK3 receptors are undoubtedly involved in the respiratory response to microinjection of NKB and senktide into the cNTS, the role of NK3 receptors in reflex integration in the NTS is unclear. Moreover, there is some uncertainty as to the source of endogenous NKB which activates NK3 receptors, since NKB is not contained in primary afferent neurons in the NTS (Nagashima et al., 1989). NKB may be involved in secondary integration or contained in neurons which project to the NTS and play a role in modifying primary transmission. Alternatively, although the actions of SP and NKA in untreated rats are not altered by the NK3 receptor antagonist SR 142801 (Mazzone & Geraghty, 2000), endogenous tachykinins are notoriously promiscuous and may activate NK3 receptors at physiological concentrations (see Mussap et al., 1993). In either case, NK3 receptors do not appear to be synaptically located in the rat NTS (Carpentier & Baude, 1996), suggesting a complex role for NK3 receptors in the reflex control of respiration.

In conclusion, these studies suggest that neonatal capsaicin pretreatment sensitizes the NTS to selected NK1, NK2 and NK3 tachykinin receptor agonists. The mechanisms underlying this sensitization are not known, but may represent reactive receptor up-regulation following chemical deafferentation of the NTS. Moreover, the apparent loss of septide responsiveness in capsaicin-pretreated rats suggests that a population of septide-sensitive NK1 receptors are located presynaptically on capsaicin-sensitive respiratory afferents in the NTS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Australian Research Council.

Abbreviations

- cNTS

commissural nucleus of the solitary tract

- f

frequency

- NK

neurokinin

- SP

substance P

- VE

minute ventilation

- VT

tidal volume

References

- BAILEY C.P., JONES R.S.G. NK2-receptor activation increases spontaneous GABA-release in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:48P. [Google Scholar]

- CAMMACK C., LOGAN S.D. Excitation of rat sympathetic preganglionic neurones by selective activation of the NK1 receptor. J. Autonom. Nerv. Sys. 1996;57:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARPENTIER C., BAUDE A. Immunocytochemical localisation of NK3 receptors in the dorsal vagal complex of rat. Brain Res. 1996;734:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIUCCI A., PALMA C., MANZINI S., WERGE T.M. Point mutation increases a form of the NK1 receptor with high affinity for neurokinin A and B and septide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:393–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROUL S., SVERSTIUK A., RADZIEVSKY A., MURRAY M. Modulation of neurotransmitter receptors following unilateral L1-S2 deafferentation: NK1, NK3, NMDA and 5HT1a receptor binding autoradiography. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;361:633–644. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE SANCTIS G.T., GREEN F.H.Y., REMMERS J.E. Ventilatory responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia in awake rats pretreated with capsaicin. J. Appl. Physiol. 1991;70:1168–1174. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.3.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLAS F.L., PALKOVITS M., BROWNSTEIN M.J. Regional distribution of substance P-like immunoreactivity in the lower brainstem of the rat. Brain Res. 1982;245:376–378. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90821-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUO A., VULCHANOVA L., WANG J., LI X., ELDE R. Immunocytochemical localization of the vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1): relationship to neuropeptides, the P2X3 purinoceptor and IB4. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:946–958. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEDNER J., HEDNER T., JONASON J. Capsaicin and regulation of respiration: interaction with central substance P mechanisms. J. Neural Trans. 1985;61:239–252. doi: 10.1007/BF01251915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELKE C.J., ESKAY R.L. Capsaicin reduces substance P immunoreactivity in the lateral nucleus of the solitary tract and nodose ganglion. Peptides. 1985;6 Supp. 1:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(85)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HELKE C.J., SHULTS C.W., CHASE T.N., O'DONOHUE T.L. Autoradiographic localization of substance P receptors in rat medulla: effect of vagotomy and nodose ganglionectomy. Neuroscience. 1984;12:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAKOB R.L., GOLDMAN-RAKIC P. Presynaptic and postsynaptic subcellular localization of substance P receptor immunoreactivity in the neostriatum of the rat and rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;369:125–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960520)369:1<125::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JORDAN D., SPYER K.M.Brainstem integration of cardiovascular and pulmonary afferent activity Progress in Brain Research 1986volume 67New York: Elsevier Science Publishers; 295–314.Cervero, F. & Morrison, J.F.B. (eds) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALIA M., FUXE K., HÖKFELT T., JOHANSSON O., LANG R., GATEN D., CUELLO C., TERENIUS L. Distribution of neuropeptide immunoreactive nerve terminals within the subnuclei of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;222:409–444. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGGI C.A., SCHWARTZ T.W. The dual nature of the tachykinin NK1 receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:351–355. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANAKER S., ZUCCI P.C. Effects of vagotomy on neurotransmitter receptors in the rat dorsal vagal complex. Neuroscience. 1993;52:427–441. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90169-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANTYH P.W., HUNT S.P. The autoradiographic localization of substance P receptors in the rat and bovine spinal cord and the rat and cat trigeminal nucleus pars caudalis and the effects of neonatal capsaicin. Brain Res. 1985;332:315–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAUBACH K.A., JONES R.S.G. Electrophysiological characterisation of tachykinin receptors in the rat nucleus of the solitary tract and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1151–1159. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZZONE S.B., GERAGHTY D.P. Respiratory action of capsaicin microinjected into the nucleus of the solitary tract: involvement of vanilloid and tachykinin receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999a;127:473–478. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZZONE S.B., GERAGHTY D.P. Altered respiratory response to substance P and reduced NK1 receptor binding in the nucleus of the solitary tract of aged rats. Brain Res. 1999b;826:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZZONE S.B., GERAGHTY D.P. Respiratory actions of tachykinins in the nucleus of the solitary tract: characterisation of receptors using selective agonists and antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:1121–1131. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUSSAP C.J., GERAGHTY D.P., BURCHER E. Tachykinin receptors: a radioligand binding perspective. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:1987–2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGASHIMA A., TAKANO Y., TATEISHI K., MATSUOKA Y., HAMAOKA T., KAMIYA H. Cardiovascular roles of tachykinin peptides in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rats. Brain Res. 1989;487:392–396. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAXINOS G., WATSON C.The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates 1986Sydney: Academic Press Inc; (2nd edition) [Google Scholar]

- STEINBERG R., RODIER D., SOUILHAC J., BOUGAULT I., EMONDS-ALT X., SOUBRIE P., LE FUR G. Pharmacological characterization of tachykinin receptors controlling acetylcholine release from rat striatum: an in vivo microdialysis study. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:2543–2548. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZALLASI A., NILSSON S., FARKAS-SZALLASI T., BLUMBERG P.M., HOKFELT T., LUNDBERG J.M. Vanilloid receptors in the rat: distribution in the brain, regional differences in the spinal cord, axonal transport to the periphery, and depletion by systemic vanilloid treatment. Brain Res. 1995;703:175–183. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZOLCSÁNYI J.Actions of capsaicin on sensory receptors Capsaicin in the Study of Pain 1993London: Academic Press; 1–27.Wood, J.N. (ed) [Google Scholar]

- TAKANO Y., NAGASHIMA A., KAMIYA H., KUROSAWA M., SATO A. Well-maintained reflex responses of sympathetic nerve activity to stimulation of baroreceptor, chemoreceptor and cutaneous mechanoreceptors in neonatal capsaicin-treated rats. Brain Res. 1988;445:188–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMINAGA M., CATERINA M.J., MALMBERG A.B., ROSEN T.A., GILBERT H., SKINNER K., RAUMANN B.E., BASBAUM A.I., JULIUS D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TREMBLAY L., KEMEL M.L., DESBAN M., GAUCHY C., GLOWINSKI J. Distinct presynaptic control of dopamine release in striosomal- and matrix-enriched areas of the rat striatum by selective agonists of NK1, NK2 and NK3 tachykinin receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:11214–11218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YASHPAL K., DAM T.-V., QUIRION R. Effects of dorsal rhizotomy on neurokinin receptor sub-types in the rat spinal cord: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1991;552:240–247. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90088-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZERARI F., KARPITSKIY V., KRAUSE J., DESCARRIES L., COUTURE R. Astroglial distribution of neurokinin-2 receptor immunoreactivity in the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1998;84:1233–1246. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]