Abstract

CS-747 is a novel antiplatelet agent that generates an active metabolite, R-99224, in vivo. CS-747 itself was totally inactive in vitro. This study examined in vivo pharmacological profiles of CS-747 after single oral administration to rats.

Orally administered CS-747 (0.3–10 mg kg−1) partially but significantly decreased [3H]-2-methylthio-ADP binding to rat platelets. CS-747 (3 mg kg−1, p.o.) treatment neutralized ADP-induced decreases of cyclic AMP concentrations induced by prostaglandin E1, suggesting that metabolites of CS-747 interfere with Gi-linked P2T receptor.

CS-747 (0.3 and 3 mg kg−1, p.o.) markedly inhibited ex vivo washed platelet aggregation in response to ADP but not to thrombin. CS-747 also exhibited a marked inhibition of ADP-induced ex vivo platelet aggregation in PRP with a rapid onset (<0.5 h) and long duration (>3 days) of action (ED50 at 4 h=1.2 mg kg−1).

R-99224 (IC50=45 μM) inhibited in vitro PRP aggregation in a concentration-related manner.

CS-747 prevented thrombus formation in a dose-related manner with an ED50 value of 0.68 mg kg−1. CS-747 was more potent than clopidogrel (6.2 mg kg−1) and ticlopidine (>300 mg kg−1).

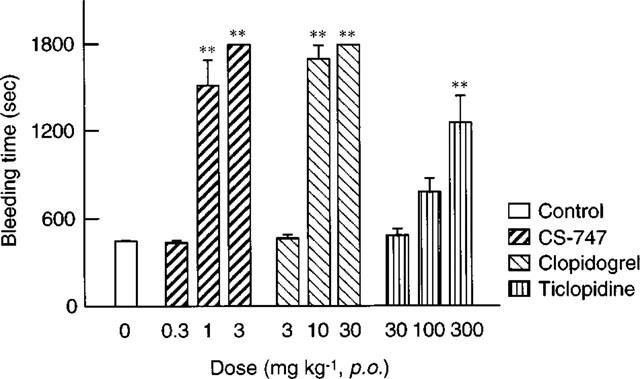

CS-747, clopidogrel, and ticlopidine prolonged the bleeding time. The order of potency of these agents in this activity was the same as that in antiaggregatory and antithrombotic activities.

These findings indicate that CS-747 is an orally active and a potent antiplatelet and antithrombotic agent with a rapid onset and long duration of action, and warrants clinical evaluations of the agent.

Keywords: Platelet aggregation, thrombosis, bleeding time, CS-747, platelet ADP receptors, active metabolite, R-99224

Introduction

The platelet activation and subsequent platelet aggregation play an essential role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases (Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration, 1988; Schrör, 1995). Upon vascular injury, ADP, a potent platelet activator, is released into the bloodstream from damaged cells and activated platelets, which in turn acts on other platelets (Gachet et al., 1996). ADP induces a number of responses in platelets, including shape change from disc to sphere, aggregation, and secretion of granule contents (Gachet & Cazenave, 1991). These responses are considered to be mediated by ADP's interaction with specific binding sites on the platelet membrane that have been tentatively designated as P2T receptors (Hourani & Hall, 1994; Gachet et al., 1996). The P2T receptors are probably composed of three distinct receptors, i.e., the P2X1, ligand gated ion channel receptors and two distinct G-protein coupled ADP receptors (a Gq-linked P2Y1 receptor and a Gi-linked P2T receptor distinct from P2Y1) (for review see Kunapuli, 1998a, 1998b).

The importance of the Gi-linked P2T receptor in platelet aggregation has been demonstrated in recent studies using ARL 66096, ticlopidine and clopidogrel (Mills et al., 1992; Fagura et al., 1998; Daniel et al., 1998). Thienopyridine derivatives such as ticlopidine and clopidogrel are orally active inhibitors of ADP-induced platelet aggregation with a slow onset and long duration of action (McTavish et al., 1990; Coukell & Markham, 1997). Previous studies have demonstrated that these agents inhibit the binding of radiolabelled 2-methylthio-ADP (2-MeS-ADP), a stable analogue of ADP, to human and animal platelets ex vivo. It has been speculated that the mechanism of those actions involves the inhibition of the Gi-linked P2T receptor (Mills et al., 1992; Savi et al., 1994a; Gachet et al., 1995), but the putative active metabolites remain to be elucidated (Saltiel & Ward, 1987; Savi et al., 1994b; Coukell & Markham, 1997). The clinical efficacy of these agents was demonstrated in human clinical trials, e.g. CATS (Gent et al., 1989). TASS (Hass et al., 1989) and CAPRIE (CAPRIE Steering Committee, 1996). However, the therapeutic doses of ticlopidine are accompanied by serious side effects such as neutropenia and abnormal liver function. Clopidogrel has been reported to be as safe as aspirin, but its therapeutic benefit compared to aspirin is marginal (CAPRIE Steering Committee, 1996).

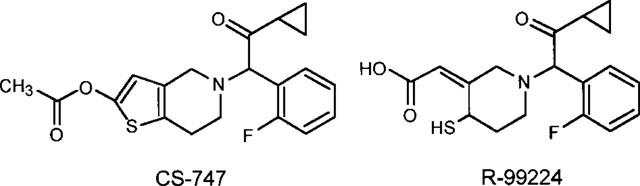

CS-747 (Figure 1) is a novel antiplatelet agent which generates an active metabolite, R-99224 (Figure 1), in vivo. In the present studies, we investigated the in vivo pharmacological profile of CS-747 in rats. In addition, we compared the antiplatelet and antithrombotic effects of single oral administrations of CS-747 to those of clopidogrel and ticlopidine. The pharmacological profile of CS-747 revealed in the present study shows its potential as an antiplatelet agent.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of CS-747 and its active metabolite, R-99224.

Methods

Animals

The experimental procedures employed in this study were in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Sankyo Research Laboratories (Tokyo, Japan). We used male Sprague-Dawley rats purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). The animals were allowed free access to standard rat chow and water.

Preparation of platelet-rich plasma and washed platelets

Rats were anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg kg−1, i.p.). Blood was drawn from the abdominal aorta into a plastic syringe containing 3.8% (w v−1) trisodium citrate (1 : 9 volumes of blood) as an anticoagulant. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared by centrifugation at 230×g for 15 min at room temperature. Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was obtained by centrifugation of the remaining blood at 2000×g for 10 min. Platelet counts in PRP were adjusted to 5×108 ml−1 by adding PPP.

Washed platelets were prepared as described previously (Sugidachi et al., 1998) with slight modifications. After prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) at 100 nM was added to the PRP, the mixture was centrifuged at 1300×g for 6 min, and the resulting platelet pellet was resuspended in a washing buffer containing (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 2.7, NaHCO3 12, NaH2PO4 0.4, MgCl2 0.8, glucose 5, HEPES 10, and 3.5 mg ml−1 fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin, pH 6.7. Finally this platelet suspension was further washed and resuspended in the suspension buffer (same composition as the washing buffer, pH 7.4). In studies on washed platelets, the platelet suspension was supplemented with 0.068 mg ml−1 human fibrinogen and 1 mM Ca2+.

[3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding

The washed platelet suspension (2×108 platelets ml−1) was incubated with 10 nM [3H]-2-MeS-ADP at room temperature. After 30 min, the reaction mixture was layered onto a 20% sucrose solution in suspension buffer and the bound ligand was separated by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 3 min at room temperature. After careful aspiration of the supernatant, the platelet pellet was dissolved in NCS-II (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, U.K.) and its radioactivity was measured by scintillation counting. Specific binding was defined as the difference between the total binding and nonspecific binding determined by addition of unlabelled 2-MeS-ADP at 100 μM.

Measurement of cyclic AMP concentration

To indirectly measure adenylyl cyclase activity, cyclic AMP levels were determined according to the method of Defreyn et al. (1991). PGE1 was used to elevate cyclic AMP levels. A mixture of 1.5 ml buffer (in mM: Tris 15, NaCl 120, KCl 4, MgSO4 1.6, NaH2PO4·2H2O 2, glucose 10, 0.2% BSA, IBMX 1.5; pH 7.4) and 3 ml PRP (5×108 platelets ml−1) was incubated at 37°C for 1 min, and then PGE1 (10 μM) was added. ADP (10 μM) or saline was added to the reaction mixture at 3 min after PGE1 stimulation. Aliquots in a volume of 0.5 ml were taken from the reaction mixture before and 1, 3, 4, and 6 min after PGE1 stimulation. These samples were supplemented with 50 μl of 6N HCl and 50 μM EDTA solution and boiled for 5 min. After rapid cooling on ice, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 5 min at 4°C. After adding CaCO3 (60 mg), the supernatants (300 μl) were incubated at room temperature for 15 min and then centrifuged again at 10,000×g for 5 min at 4°C. The final supernatants were assayed for cyclic AMP levels using a commercially available EIA kit (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, U.K.).

Measurement of ex vivo platelet aggregation and shape change

All aggregation studies were performed in Mebanix aggregometers (model PAM-6C and PAM-8C, Tokyo, Japan). The washed platelets (3×108 platelets ml−1) or PRP (5×108 platelets ml−1) in a volume of 240 μl were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 min in the aggregometer with continuous stirring at 1000 r.p.m. and then stimulated with 10 μl of ADP, collagen, or thrombin. Changes in light transmission were recorded for 7 min (ADP) and for 10 min (collagen and thrombin) after stimulation with these agents. The extent of aggregation was expressed as a percentage of the maximum light transmittance, obtained with the suspension buffer (washed platelet aggregation) or PPP (PRP aggregation). Platelet shape change was determined using an aggregometer, PAM-6C according to the method by Michal & Motamed (1976), and was estimated quantitatively by measuring the maximum height above baseline level.

Arterio-venous shunt thrombosis model

The ability of test agents to prevent thrombus formation was assessed using an arterio-venous shunt model originally described by Umetsu & Sanai (1978) with slight modifications. After anaesthesia with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg kg−1, i.p.), the jugular vein and contralateral carotid artery of rats were exposed and they were cannulated with a polyethylene cannula which contains a silk thread in its lumen and is filled with heparin solution (30 unit kg−1). Blood circulation was started through the cannula allowing thrombus formation to occur on the silk thread. After a 30 min circulation, the cannula tube was removed and the silk thread was weighed. The weight of thrombus formed on the thread was calculated by deducting the wet weight of an equivalent length of the standard thread. Drugs or vehicle were administered 4 h before starting blood flow.

Bleeding time

The tail transection bleeding time was determined by the method of Dejana et al., (1979). The test drugs were orally administered 4 h before the tail transection. Under anaesthesia with pentobarbital (40 mg kg−1, i.p.), the rat tail was transected at 4 mm from the tip by a scalpel, and the tail was immediately immersed into warmed (37°C) saline until blood flow stopped. Bleeding time was assessed as the time from the tail transection to the termination of blood flow. Bleeding times beyond 1800 s were regarded as 1800 s for the purpose of statistical analysis. The BT2 was defined as the dose that doubled the control bleeding time.

Drugs and administration

CS-747 (2-acetoxy-5-(α-cyclopropylcarbonyl-2-fluorobenzyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno [3,2-c]pyridine), R-99224 ((2Z)-[1-[2-cyclopropyl-1-(2-fluorophenyl) - 2 - oxoethyl] -4-mercapto-3-piperidinylidene] acetic acid, trifluoroacetate), and clopidogrel hydrogensulphate (SR25990C) were synthesized by Ube Industries (Yamaguchi, Japan). Ticlopidine hydrochloride, ADP (sodium salt), human fibrinogen, fatty-acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), N-2-hydroxylethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES), apyrase and gum arabic were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Collagen was from Nycomed (Munich, Germany), heparin (sodium salt) was from Fuso (Osaka, Japan). PGE1 was from Funakoshi (Tokyo, Japan), and bovine thrombin was from Mochida (Tokyo, Japan). [3H]-2-MeS-ADP (ammonium salt, specific activity 85 Ci mmol−1) was obtained from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, U.K.), and 2-MeS-ADP (trisodium salt) was obtained from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, U.S.A.).

CS-747, clopidogrel, and ticlopidine were suspended in 5% gum arabic solution at appropriate concentrations and orally administered to rats in a volume of 1 ml kg−1 body weight. All experiments included the vehicle-treated control groups. In in vitro study. R-99224 and CS-747 were dissolved in DMSO, and added to the PRP; the final concentration of DMSO was 0.4%.

Statistics

Results were expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Approximate estimate of the ED50 and BT2 values were calculated from linear-regression analysis. Dunnett's test for multiple comparison was used to determine significance of differences between mean values within groups. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

[3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding

Preliminary studies showed that [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding to rat platelets was time-related and saturable, with an apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of 2.37±0.27 nM and a total number of receptor sites (Bmax) of 180.2±13.8 fmol 108 platelets−1 (n=4). In vitro treatment with CS-747 (100 and 300 μM) had no effects on [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding to the washed platelets of rats (data not shown).

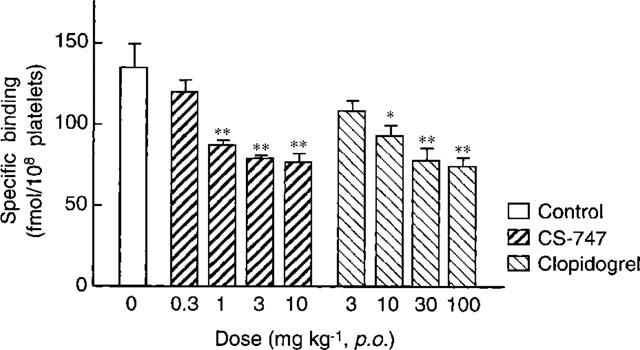

Ex vivo effects of CS-747 (0.3–10 mg kg−1, p.o.) and clopidogrel (3–100 mg kg−1, p.o.) on [3H]-2-MeS-ADP (10 nM) binding to rat platelets were examined 4 h after dosing. After 30 min incubation, the specific [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding to platelets from vehicle-treated control rats was 134.4±15.2 fmol 108 platelets−1 (n=6). As shown in Figure 2, [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding was significantly (P<0.01) decreased in platelets from rats given CS-747 (1–10 mg kg−1, p.o.). But the inhibition remained partial (approximately 43%) even at a dose of CS-747 as high as 10 mg kg−1. Orally administered clopidogrel also showed similar partial inhibition of [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding to rat platelets, but clopidogrel was about ten times less potent than CS-747 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ex vivo effects of CS-747 on specific [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding to rat washed platelets. CS-747 (0.3–10 mg kg−1) and clopidogrel (3–100 mg kg−1) were orally administered to rats 4 h before blood collection. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control.

Cyclic AMP levels in platelets

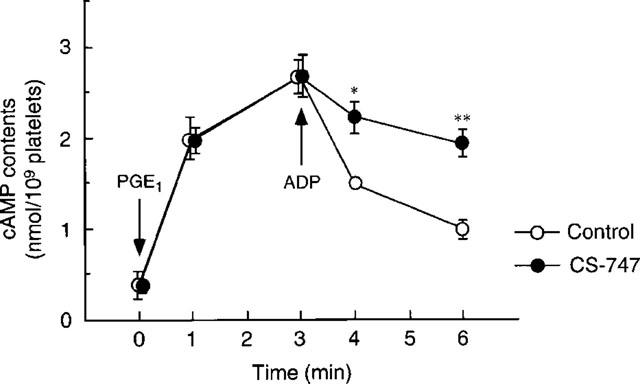

Since ADP inhibits adenylyl cyclase via activation of Gi protein (Defreyn et al., 1991; Ohlmann et al., 1995), we examined the ex vivo effects of CS-747 on ADP-mediated suppression of PGE1-induced cyclic AMP elevation. An addition of PGE1 (10 μM) produced a progressive increase of intraplatelet cyclic AMP levels, indicating the activation of adenylyl cyclase. The elevated cyclic AMP levels were suppressed by ADP (10 μM) added 3 min after PGE1 stimulation. As shown in Figure 3, the inhibitory effect of ADP (10 μM) on elevated cyclic AMP levels was inhibited substantially in platelets from CS-747 (3 mg kg−1, p.o.)-treated rats. There was no difference in the basal cyclic AMP levels between CS-747-treated (0.39±0.15 nmol 109 platelets−1, n=5) and vehicle-treated platelets (0.37±0.06 nmol 109 platelets−1, n=5).

Figure 3.

Ex vivo effects of CS-747 on ADP (10 μM)-induced cyclic AMP decrease in PGE1 (10 μM)-stimulated rat platelets. CS-747 (3 mg kg−1) was orally administered to rats 4 h before blood collection. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean (n=5). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control.

Ex vivo and in vitro platelet aggregation

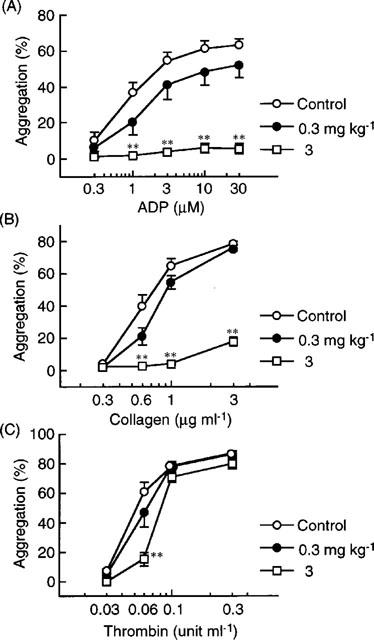

Washed platelets

To eliminate possible fibrin production induced by thrombin, experiments to test agonist selectivity was performed using washed platelets. A single oral administration of CS-747 (0.3 and 3 mg kg−1) produced a dose-related inhibition of ADP (0.3–30 μM)-induced ex vivo aggregation in washed platelets (Figure 4A). Collagen (0.3–3 μg ml−1)-induced aggregation was also inhibited by CS-747 administration in a dose-related manner (Figure 4B). In contrast, CS-747 moderately inhibited platelet aggregation induced by a low concentration of thrombin (0.06 unit ml−1), but not that by high concentrations of thrombin (0.1 and 0.3 unit ml−1) (Figure 4C). Apyrase (0.3 and 3 IU ml−1) also inhibited platelet aggregation induced by ADP (30 μM) and collagen (3 μg ml−1), but not by thrombin (0.3 unit ml−1) (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Ex vivo effects of single administration of CS-747 on washed platelet aggregation induced by ADP (A), collagen (B), and thrombin (C) in rats. CS-747 was orally administered once to rats at doses of 0.3 and 3 mg kg−1. The aggregation was measured 4 h after the dosing. Results are presented as the mean±s.e.mean (n=6). **P<0.01 vs control (vehicle-treated group).

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP)

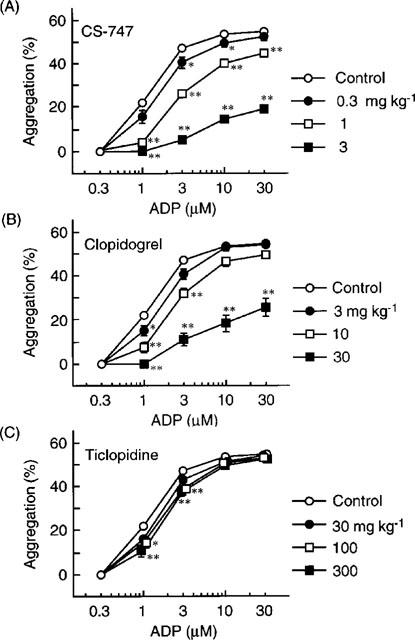

PRP was prepared from rats administered with a single dose of CS-747 (0.3–3 mg kg−1, p.o.). Figure 5 shows the ex vivo effects of CS-747 on a concentration-aggregation curve for ADP determined at 4 h post-dose. We also investigated the antiaggregatory effects of clopidogrel and ticlopidine, two existing platelet ADP receptor inhibitors. A single oral administration of clopidogrel (3–30 mg kg−1) caused a dose-related inhibition of ADP-induced aggregation, but the inhibitory effects of ticlopidine (30–300 mg kg−1) were minimal. Table 1 summarizes ED50 values for CS-747 (1.2 mg kg−1), clopidogrel (16 mg kg−1) and ticlopidine (>300 mg kg−1) against ADP (3 μM)-induced platelet aggregation determined at 4 h post-dose. Typical tracing of platelet aggregation induced by ADP (3 μM) in PRP from rats treated with CS-747 is shown in Figure 6. As can be seen, CS-747 (1 and 3 mg kg−1, p.o.) suppressed the maximum extent of platelet aggregation in a dose-related manner. Similar effects on platelet aggregation were obtained with clopidogrel and ticlopidine (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Ex vivo effects of single administration of CS-747 (A), clopidogrel (B), and ticlopidine (C) on ADP-induced platelet aggregation in rats. The aggregation in PRP was measured 4 h after the oral dosing. Results are presented as the mean±s.e.mean (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control (vehicle-treated group).

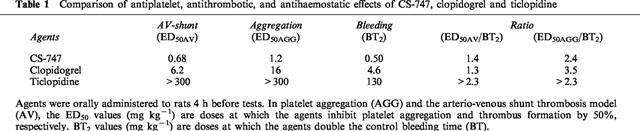

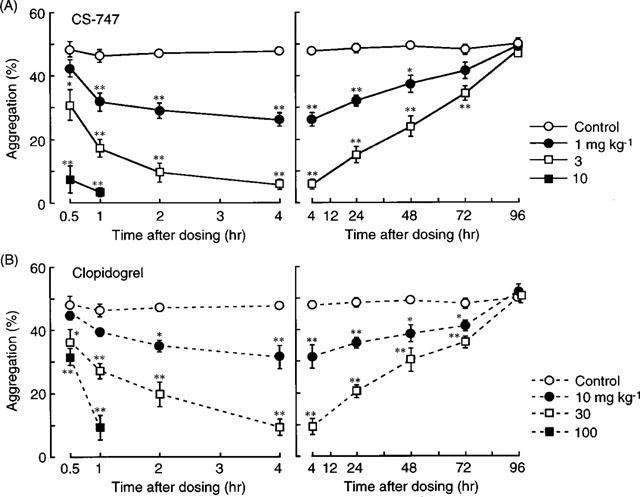

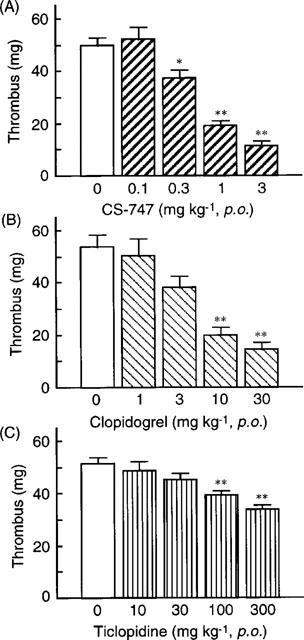

Table 1.

Comparison of antiplatelet, antithrombotic, and antihaemostatic effects of CS-747, clopidogrel and ticlopidine

Figure 6.

Representative aggregometer tracing showing the ex vivo effect of CS-747 (A) and in vitro effect of R-99224 (B) on ADP-induced platelet aggregation in rat PRP. CS-747 (1 and 3 mg kg−1, p.o.) inhibited ADP (1–30 μM)-induced platelet aggregation. R-99224 (7.53–75.3 μM) inhibited 10 μM ADP-induced aggregation.

We also determined that in vitro effect of R-99224, a metabolite for CS-747, on ADP (10 μM)-induced platelet aggregation in rat PRP. Figure 6 shows typical changes in ADP induced aggregation tracing at different concentration of R-99224. Note that the ex vivo effects of CS-747 and in vitro effect of R-99224 on aggregation were similar (Figure 6). R-99224 (7.53–75.3 μM) produced a concentration-related inhibition of platelet aggregation with an IC50 value of 44.9 μM. In contrast, CS-747 (30–300 μM) showed minimal effects on in vitro rat platelet aggregation, and the maximal inhibition at 300 μM was 9.0±2.7% (the IC50 value >300 μM, n=5).

Time course study

The time course of the anti-aggregatory effect of CS-747 (1–10 mg kg−1) after a single oral dosing were examined in comparison with clopidogrei (10–100 mg kg−1). As shown in Figure 7A, a more than 80% inhibition was observed in CS-747 (10 mg kg−1, p.o.)-treated rats at 0.5 h after dosing. At this time, clopidogrel exhibited minimal inhibition even at the highest dose used (100 mg kg−1. p.o.) (Figure 7B). The inhibitions of platelet aggregation by CS-747 (1–3 mg kg−1, p.o.) and clopidogrel (10–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) reached a plateau within 2 and 4 h post-dose, respectively. The inhibition of platelet aggregation by CS-747 was of long duration: a slight but significant inhibition was observed at 72 h post-dose in the CS-747-treated rats (Figure 7A). At 96 h post-dose there were no differences in platelet aggregation between the control and CS-747-treated groups. The long duration of antiaggregatory effects was also observed in the clopidogrel-treated animals (Figure 7B). The ex vivo effects of CS-747 on ADP (0.03–1 μM)-induced platelet shape changes were determined at 4 h post-dose. Orally administered CS-747 (1 and 3 mg kg−1, p.o.) did not significantly affect ADP-induced shape changes (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Time courses of the antiplatelet effects of CS-747 (A) and clopidogrel (B). Ex vivo platelet aggregation in PRP was measured at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after the single oral administration of the agents. ADP at a concentration of 3 μM was used as an agonist. Results are presented as the mean±s.e.mean (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control (vehicle-treated group).

Antithrombotic effects in a rat arterio-venous shunt model

A rat model of arterio-venous shunt (Umetsu & Sanai, 1978; Sugidachi et al., 1993) was used to examine the antithrombotic effects of CS-747 in comparison with those of clopidogrel and ticlopidine (Figure 8). After a 30 min circulation of blood through the canula, the weights of the thrombus formed on the silk thread were not different among the three control groups. In the CS-747 (0.1–3 mg kg−1, p.o.) groups, thrombus formation was decreased in a dose-related manner, and the ED50 value was estimated as 0.68 mg kg−1. Clopidogrel (1–30 mg kg−1, p.o.) also decreased thrombus weight in a dose-related manner, with an estimated ED50 value of 6.2 mg kg−1. Ticlopidine (10–300 mg kg−1, p.o.) produced a significant decrease of thrombus weight, but the ED50 value was not obtained (>300 mg kg−1) since the maximum inhibition was less than 40%.

Figure 8.

Effects of single administration of CS-747 (A), clopidogrel (B), and ticlopidine (C) on the arterio-venous shunt thrombosis model in rats. Blood circulation was started 4 h after the oral administration of the agents. Results are presented as the mean±s.e.mean (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control (vehicle-treated group).

Bleeding time

Rat tail transection bleeding time (Dejana et al., 1979; Sugidachi et al., 1993) was measured to determine antihaemostatic effects of CS-747 in comparison to those of clopidogrel and ticlopidine. The bleeding time averaged 446±16 s (n=7) in the vehicle-treated control group. All the drugs tested prolonged bleeding time in a dose-related manner (Figure 9). The BT2 values of CS-747, clopidogrel, and ticlopidine were 0.50, 4.6, and 130 mg kg−1 (p.o.), respectively. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of these agents, the ratios of ED50 for antiplatelet (ED50AGG) and antithrombotic (ED50AV) potencies to BT2 values were calculated for each agent (Table 1).

Figure 9.

Effects of single administration of CS-747, clopidogrel, and ticlopidine on tail transection bleeding time in rats. Agents were orally administered to rats 4 h before the tail transection. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.mean (n=7). **P<0.01 vs control (vehicle-treated group).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that CS-747 was a potent inhibitor of the Gi-linked P2T receptor ex vivo. Through this work, we showed that the inhibition of Gi-linked P2T receptor with CS-747 produced a specific and dose-related inhibition of ex vivo ADP-induced platelet aggregation which developed rapidly and lasted for a long period of time. CS-747 had potent antithrombotic effects in a rat model of arterial thrombosis, and antihaemostatic action in the rat bleeding-time assay. In contrast to these potent ex vivo and in vivo activities, CS-747 was inactive in vitro. R-99224, an in vivo metabolite of CS-747, however, produced a concentration-related inhibition of in vitro PRP aggregation. Thus, as in the case of clopidogrel and ticlopidine, in vivo activities of CS-747 are attributed to its active metabolite.

2-MeS-ADP is a stable agonist for P2Y1 and Gi-linked P2T receptor (Kunapuli, 1998a,1998b). A single oral administration of CS-747 produced a significant but partial inhibition (about 43% inhibition at 10 mg kg−1) of [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding to platelets in the ex vivo study (Figure 2). Clopidogrel (100 mg kg−1) also showed similar partial inhibition of [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding. This agreed with the previous findings that clopidogrel and ticlopidine produced partial inhibition of [3H]-2-MeS-ADP binding to platelets (Savi et al., 1994a; Gachet et al., 1995), although the extent of maximal inhibition (%) was greater than our present study (approximately 70% vs 45%). This difference in maximal inhibition between the present study and the aforementioned studies may involve the use of different gender of rats or different technique of separation of the radioligand.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the platelet ADP receptor is not homogeneous. In addition to the ligand-gated ion channel P2X1 receptor (MacKenzie et al., 1996), two subclasses of G-protein-coupled ADP receptors have been proposed to exist on human platelet membranes: the Gq-linked P2Y1 receptor and a Gi-linked P2T receptor (Fagura et al., 1998; Daniel et al., 1998; Jantzen et al., 1998). The Gi-linked P2T receptor has also been suggested to exist in platelets in the rat and the rabbit (Defreyn et al., 1991; Savi et al., 1996). Indeed, our present study confirmed that ADP lowers cyclic AMP concentration in rat platelets stimulated with PGE1, an activator of adenylyl cyclase, and that CS-747 treatment inhibited this effect (Figure 3). In addition, CS-747 did not affect P2Y1-mediated platelet shape change. These results suggest that metabolites of CS-747 selectively interfere with the Gi-linked P2T receptor on rat platelet membranes.

Treatment with CS-747 inhibited ex vivo washed platelet aggregation in response to ADP but not to thrombin (Figure 4). This is consistent with the hypothesis that the antiaggregative action of CS-747 is due to its specific inhibition of the Gi-linked P2T receptor rather than its interference with the fibrinogen receptors. Nonetheless, collagen-induced aggregation was inhibited by CS-747, but this may be interpreted on the basis of previous studies demonstrating that platelet-derived ADP plays a major role in collagen-induced aggregation of rat platelets (Wey et al., 1982; Tschopp & Zucker, 1972; Emms & Lewis, 1986). Indeed, apyrase, an ADP scavenger, has similar inhibitory profile on rat washed platelet aggregation. Hence, the inhibition of collagen-induced aggregation by CS-747 is most probably attributed to inhibition of the effects of ADP released from the dense granules of collagen-stimulated platelets.

The present study showed that CS-747 possesses an antiaggregatory efficacy approximately ten times more potent than that of clopidogrel (Figures 5 and 7). In sharp contrast, a single administration of ticlopidine caused minimal inhibition of platelet aggregation. This is in agreement with previous studies demonstrating clear antiaggregative effects of ticlopidine only after repeated administrations in humans (McTavish et al., 1990). In addition, the time course study showed that CS-747 (10 mg kg−1) had a more rapid onset (<0.5 h) of antiaggregatory action than clopidogrel (Figure 7). The rapid onset of CS-747 was observed not only in rats but in various species including human (unpublished data). Although the precise mechanism responsible for the rapid onset of CS-747 remains to be elucidated, one possible explanation is that CS-747 may be more rapidly metabolized to its active metabolite in vivo. Ticlopidine and clopidogrel, which are inactive in vitro, reportedly must undergo hepatic metabolism to become active (Savi et al., 1992), and it has been suggested that the metabolic activation of clopidogrel involves the cytochrome P450-1A subfamily (Savi et al., 1994b). Further study is necessary to determine the metabolic pathways of CS-747, but the agent is speculated, based on its chemical structure, to generate active metabolites more readily than clopidogrel.

The time course study also showed that CS-747 had a long duration of antiaggregatory action. In fact, the durations of inhibition of platelet aggregation by CS-747 and clopidogrel in this study were comparable to the life span of circulating platelets in the rat (Cattaneo et al., 1985; Jackson et al., 1992). In addition, the antiaggregatory effects of CS-747 observed in washed platelets were not easily reversed by washing of platelets. Hence, it is likely that CS-747 inhibits platelet aggregation in an irreversible manner. Taken together, these results suggest that the active metabolite of CS-747 exerts antiaggregatory action through an irreversible modification of the Gi-linked P2T receptor on the membrane surface. Further studies are now underway to investigate the in vitro interaction between an active metabolite of CS-747 and platelet ADP receptors.

Several lines of evidence suggest that in vivo antiplatelet effects of thienopyridine derivatives are due to their active metabolite(s) as described above. But the active metabolites have not yet been reported so far. In contrast, Weber et al. (1999) reported that incubation of washed platelets with clopidogrel resulted in inhibition of ADP-induced in vitro platelet aggregation without hepatic bioactivation. This report also showed that clopidogrel did not show any inhibition of in vitro aggregation in PRP. Our present study confirmed that CS-747 did not show any inhibition of ADP-induced PRP aggregation. The present results, however, showed that R-99224, an in vivo metabolite for CS-747, inhibits ADP-induced in vitro platelet aggregation in the presence of plasma (Figure 6). Our preliminary results also have shown that R-99224 shows more potent antiaggregatory activity in washed platelets. To our knowledge, this is the first report that described the active metabolite for thienopyridine derivatives. Taken together, the inhibitory effects of CS-747 on platelet aggregation are, at least in part, likely to depend on its active metabolite, R-99224.

A rat model of arterio-venous shunt thrombosis has been extensively studied and used to examine antithrombotic effects of various agents (Maffrand et al., 1988; Herbert et al., 1996; Odawara et al., 1996). In this model, CS-747 showed a potent antithrombotic efficacy that exceeds the potencies of clopidogrel and ticlopidine. The order of antithrombotic potencies among these agents was the same as the order of antiaggregatory potencies (Figure 8). In addition, CS-747 was devoid of in vitro and ex vivo anticoagulant or fibrinolytic activities (data not shown). Thus, the available data support the view that CS-747 exerts its antithrombotic effects by inhibiting the interaction between ADP and its receptors on the platelet membrane.

In this study, CS-747, clopidogrel, and ticlopidine all showed a significant and dose-related prolongation of the rat tail transection bleeding time (Figure 9). The order of the antihaemostatic potency among these agents was the same as the order of antiplatelet and antithrombotic potencies. In addition, the ratios of antithrombotic dose (ED50AV) and antiaggregatory dose (ED50AGG) to antihaemostatic dose (BT2) for CS-747 and clopidogrel were approximately the same (Table 1). From these comparative studies, CS-747 and clopidogrel may have a similar ratio of benefit/bleeding risk. This might be clinically important, since clopidogrel is clinically available and its benefit/bleeding risk ratio has been identified in a large clinical study (CAPRIE Steering Committee, 1996). It should be noted that a single administration of ticlopidine produced a marked prolongation of bleeding time, whereas the same dose ranges of this agent exerted only mild to moderate antiplatelet and antithrombotic actions. Taken together, these results suggest that CS-747 is a potent antithrombotic and antiplatelet agent with relatively moderate antihaemostatic potency, but this remains to be proven in future clinical studies.

The present study demonstrated that CS-747 is orally active and produces a potent antiplatelet and antithrombotic action with a rapid onset and long duration via platelet ADP receptors antagonism. CS-747 merits clinical evaluation in a variety of thrombotic diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Naoko Suzuki and Ms Takako Nagasawa for their expert technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ADP

adenosine 5′-diphosphate

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxylethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- 2-MeS-ADP

2-methylthio-adenosine 5′-diphosphate

- PGE1

prostaglandin E1

- PPP

platelet-poor plasma

- PRP

platelet-rich plasma

References

- ANTIPLATELET TRIALISTS' COLLABORATION Secondary prevention of vascular disease by prolonged antiplatelet treatment. Br. Med. J. 1988;296:320–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAPRIE STEERING COMMITTEE A randomized, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE) Lancet. 1996;348:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CATTANEO M., WINOCOUR P.D., SOMERS D.A., GROVES H.M., KINLOUGH-RATHBONE R.L., PACKHAM M.A., MUSTARD J.F. Effect of ticlopidine on platelet aggregation, adherence to damaged vessels, thrombus formation and platelet survival. Thromb. Res. 1985;37:29–43. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(85)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUKELL A.J., MARKHAM A. Clopidogrel. Drugs. 1997;54:745–750. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANIEL J.L., DANGELMAIER G., JIN J., ASHBY B., SMITH J.B., KUNAPULI S.P. Molecular basis for ADP-induced platelet activation. I. Evidence for three distinct ADP receptors on human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2024–2029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEFREYN G., GACHET C., SAVI P., DRIOT F., CAZENAVE J.P., MAFFRAND J.P. Ticlopidine and clopidogrel (SR 25990C) selectively neutralize ADP inhibition of PGE1-activated platelet adenylyl cyclase in rats and rabbits. Thromb. Haemost. 1991;65:186–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEJANA E., CALLIONI A., QUINTANA A., DE GAETANO G. Bleeding time in laboratory animals. II–A comparison of different assay conditions in rats. Thromb. Res. 1979;15:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(79)90064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMMS H., LEWIS G.P. The role of prostaglandin endoperoxides, thromboxane A2 and adenosine diphosphate in collagen-induced aggregation in man and the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGURA M.S., DAINTY I.A., MCKAY G.D., KIRK I.P., HUMPHRIES R.G., ROBERTSON M.J., DOUGALL I.G., LEFF P. P2Y1-receptors in human platelets which are pharmacologically distinct from P2Y (ADP)-receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:157–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GACHET C., CATTANEO M., OHLMANN P., HECHLER B., LECCHI A., CHEVALIER J., CASSEL D., MANNUCCI P.M., CAZENAVE J.P. Purinoceptors on blood platelets: further pharmacological and clinical evidence to suggest the presence of two ADP receptors. Br. J. Haematol. 1995;91:434–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GACHET C., CAZENAVE J.P. ADP induced blood platelet activation: a review. Nouv. Rev. Fr. Hematol. 1991;33:347–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GACHET C., HECHLER B., LÈON C., VIAL C., OHLMANN P., CAZENAVE J.P. Purinergic receptors on blood platelets. Platelets. 1996;7:261–267. doi: 10.3109/09537109609023587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GENT M., BLAKELY J.A., EASTON J.D., ELLIS D.J., HACHINSKI V.C., HARBISON J.W., PANAK E., ROBERTS R.S., SICURELLA J., TURPIE A.G. The Canadian American Ticlopidine Study (CATS) in thromboembolic stroke. Lancet. 1989;i:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASS W.K., EASTON J.D., ADAMS H.P., JR, PRYSE-PHILLIPS W., MOLONY B.A., ANDERSON S., KAMM B. A randomized trial comparing ticlopidine hydrochloride with aspirin for the prevention of stroke in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;321:501–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908243210804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERBERT J.M., BERNAT A., SAMAMA M., MAFFRAND J.P. The antiaggregating and antithrombotic activity of ticlopidine is potentiated by aspirin in the rat. Thromb. Haemost. 1996;76:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOURANI S.M.O., HALL D.A. Receptors for ADP on human blood platelets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACKSON C.W., STEWARD S.A., ASHMUN R.A., MCDONALD T.P. Megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production are stimulated during late pregnancy and early postpartum in the rat. Blood. 1992;79:1672–1678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANTZEN H.-M., GOUSSET L., BHASKAR V., VINCENT D., TAI A., REYNOLDS E.E., CONLEY P.B. Evidence for two distinct G-protein-coupled ADP receptors mediating platelet activation. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;81:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNAPULI S.P. Multiple P2 receptor subtypes on platelets: a new interpretation of their function. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998a;19:391–394. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNAPULI S.P. Functional characterization of platelet ADP receptors. Platelets. 1998b;9:343–351. doi: 10.1080/09537109876401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKENZIE A.B., MAHAUT-SMITH M.P., SAGE S.O. Activation of receptor-operated cation channels via P2X1 not P2T purinoceptors in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2879–2881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAFFRAND J.P., BERNAT A., DELEBASSEE D., DEFREYN G., CAZENAVE J.P., GORDON J.L. ADP plays a key role in thrombogenesis in rats. Thromb. Haemost. 1988;59:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCTAVISH D., FAULDS D., GOA K.L. Ticlopidine. An updated review of its pharmacology and therapeutic use in platelet-dependent disorders. Drugs. 1990;40:238–259. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199040020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHAL E., MOTAMED M. Shape change and aggregation of blood platelets: interaction between the effects of adenosine diphosphate, 5-hydroxytryptamine and adrenaline. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1976;56:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb07444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLS D.C., PURI R., HU C.J., MINNITI C., GRANA G., FREEDMAN M.D., COLMAN R.F., COLMAN R.W. Clopidogrel inhibits the binding of ADP analogues to the receptor mediating inhibition of platelet adenylate cyclase. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1992;12:430–436. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.4.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ODAWARA A., KIKKAWA K., KATOH M., TORYU H., SHIMAZAKI T., SASAKI Y. Inhibitory effects of TA-993, a new 1,5-benzothiazepine derivative, on platelet aggregation. Circ. Res. 1996;78:643–649. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHLMANN P., LAUGWITZ K.L., NURNBERG B., SPICHER K., SCHULTZ G., CAZENAVE J.P., GACHET C. The human platelet ADP receptor activates Gi2 proteins. Biochem. J. 1995;312:775–779. doi: 10.1042/bj3120775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALTIEL E., WARD A. Ticlopidine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in platelet-dependent disease states. Drugs. 1987;34:222–262. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198734020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAVI P., COMBALBERT J., GAICH C., ROUCHON M.C., MAFFRAND J.P., BERGER Y., HERBERT J.M. The antiaggregating activity of clopidogrel is due to a metabolic activation by the hepatic cytochrome P450-1A. Thromb. Haemost. 1994b;72:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAVI P., HERBERT J.M., PFLIEGER A.M., DOL F., DELEBASSEE D., COMBALBERT J., DEFREYN G., MAFFRAND J.P. Importance of hepatic metabolism in the antiaggregating activity of the thienopyridine clopidogrel. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;44:527–532. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90445-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAVI P., LAPLACE M.C., MAFFRAND J.P., HERBERT J.M. Binding of [3H]-2-methylthio ADP to rat platelets–effect of clopidogrel and ticlopidine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994a;269:772–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAVI P., PFLIEGER A.M., HERBERT J.M. cAMP is not an important messenger for ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 1996;7:249–252. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199603000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRÖR K. Antiplatelet drugs. Drugs. 1995;50:7–28. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199550010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGIDACHI A., ASAI F., KOIKE H. In vivo pharmacology of aprosulate, a new synthetic polyanion with anticoagulant activity. Thromb. Res. 1993;69:71–80. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUGIDACHI A., OGAWA T., ASAI F., SAITO S., OZAKI H., FUSETANI N., KARAKI H., KOIKE H. Inhibition of rat platelet aggregation by mycalolide-B, a novel inhibitor of actin polymerization with a different mechanism of action from cytochalasin-D. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;79:614–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSCHOPP T.B., ZUCKER M.B. Hereditary defect in platelet function in rats. Blood. 1972;40:217–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UMETSU T., SANAI K. Effect of 1-methyl-2-mercapto-5-(3-pyridyl)-imidazole (KC-6141), an anti-aggregating compound, on experimental thrombosis in rats. Thromb. Haemost. 1978;39:74–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER A.A., REIMANN S., SCHRÖR K. Specific inhibition of ADP-induced platelet aggregation by clopidogrel in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:415–420. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEY H., GALLON L., SUBBIAH M.T.R. Prostaglandin synthesis in aorta and platelets of fawn-hooded rats with platelet storage pool disease and its response to cholesterol feeding. Thromb. Haemostas. 1982;48:94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]