Abstract

Phencyclidine (PCP), a non-competitive NMDA-receptor antagonist, is able to induce schizophrenia-like symptoms in animals and in humans. It is known that schizophrenic patients have deficits in memory processes.

Therefore, it was investigated whether subchronic pulsatile or continuous application of 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP over 5 days induce short-term memory deficits in holeboard learning and the action of two different neuroleptics on this behavioural test.

First, an impairment in the holeboard task was described when the animals were tested 24 h after the last application but not after 15 min or 1 h after the last injection. Secondly, the influence of haloperidol and risperidone on the PCP-induced short-term memory changes was tested.

The combined application of PCP and risperidone led to a complete antagonism of the short-term deficits, but the combined treatment with haloperidol was accompanied by a partial abolishment of the PCP-induced deficits.

PCP led to an upregulation of the glutamate binding sites in striatum and nucleus accumbens whereas the D2 binding sites were reduced in striatum. The D1 binding sites seem to be unchanged. The receptor protein expression of glutamate receptors mGluR1, GluR2, GluR5/7 and NMDAR1 were not modified in response to PCP treatment.

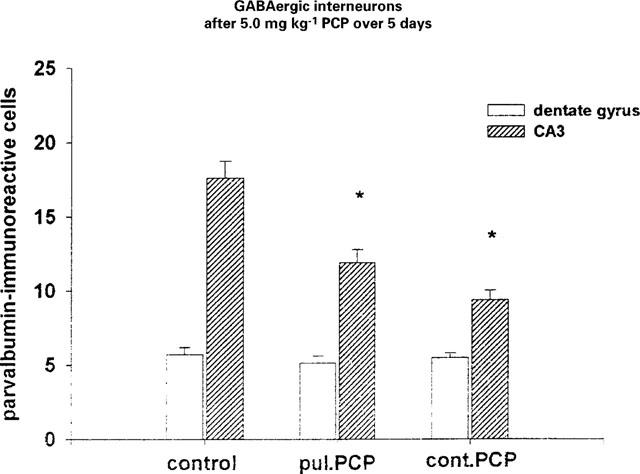

The determination of a subpopulation of GABAergic interneurons shows a decrease of the cells within the CA3 of the hippocampal formation.

These findings indicate that PCP induced impairments in short term memory can be detected by holeboard learning and may provide an interesting tool for the search of new neuroleptics.

Keywords: Binding sites, GABAergic interneurons, haloperidol, phencyclidine, risperidone, short-term memory, schizophrenia

Introduction

In addition to a disturbed dopaminergic system, schizophrenia is characterized by alterations in the glutamatergic system as well, as indicated by studies with phencyclidine (PCP). Phencyclidine, a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, has psychotomimetic effects and in healthy humans a single PCP injection produces clinical symptoms similar to schizophrenia. Repeated applications can evoke long-lasting symptoms such as neuropsychological deficits, social withdrawal, hallucinations, paranoia, and delusions (Jentsch et al., 1997a) persisting for a period far in excess of the half-life of PCP (Pearlson, 1981). Cognitive deficits in schizophrenic patients are stable and prominent and include attention deficits, deficits in memory functions, particularly episodic memory (i.e. difficulty in retrieving episodes of experience of distinct spatio-temporal contexts) (Goldberg & Gold, 1995). Most chronic PCP-abusers develop reduced and disturbed cognitive functions whereas the other symptoms may differ (Fauman & Fauman, 1980). It has been proposed that cognitive deficits result from frontal lobe dysfunction because frontal lobe lesions in humans and monkeys are associated with comparable cognitive dysfunctions i.e. working memory deficits (Goldman-Rakic, 1991).

Furthermore, PCP induces neuronal degeneration and alters glucose utilization in limbic structures including hippocampus and various cortical regions (Ellison, 1995; Tamminga et al., 1987). There is morphological and functional evidence that alterations in the same limbic regions are present in schizophrenics (Bogerts, 1997; Ellison, 1995; Tamminga et al., 1991). In addition, postmortem analysis of schizophrenics revealed a hypofunction of GABAergic interneurons in the brain as revealed by loss of GABAergic neurons, decreased GAD67 activity (the enzyme responsible for GABA synthesis) and mRNA, and upregulation of GABAA receptors (Akbarian et al., 1995; Benes et al., 1991). It is thought that PCP can alter the activity of GABAergic neurons through NMDA receptors on GABAergic interneurons in cortical and limbic structures (Coyle, 1996; Benes et al., 1991; Olney & Farber, 1997; Olney et al., 1989) with subsequent alterations of glutamatergic efferents from these regions. Furthermore, it was shown in human postmortem and rodent studies that NMDA receptor hypofunction as well as NMDA antagonism could result in a dopaminergic hyperactivity (Olney & Farber, 1995; Tsai et al., 1995), showing that glutamatergic neurons may act on dopaminergic neurons and GABAergic interneurons and thus be involved in the pathogenesis of psychosis.

Therefore, PCP has been used to induce schizophrenia-like symptoms similar to those induced by dopamine related drugs. PCP evokes a complex syndrome of behaviours with both negative and positive symptoms. The administration of PCP to rats disturbs learning performance in various hippocampus-dependent tasks. All of these behaviours appear to depend upon hippocampal as well as amygdalar function (Jones et al., 1990; Kesner & Dakis, 1993; Murray & Ridley, 1997).

In contrast to acute PCP injections, subchronic PCP treatment produces behavioural symptoms which are more stable and persist longer, rendering them similar to the chronic schizophrenia-like symptoms (Krystal et al., 1994). Recently, we have found that rats treated by pulsatile PCP injections were impaired in their ability in active two-way avoidance learning and did not develop deficits in latent inhibition, whereas rats given PCP continuously via implanted polymers were unimpaired in two-way avoidance acquisition, but they were impaired in latent inhibition which simulates a cognitive dysfunction characteristic for attentional deficits described for certain forms of schizophrenia (Schroeder et al., 1998).

Because there is little information about subchronic PCP effects on short-term cognitive processes and associated neurochemical and morphological alterations, the purpose of the present study was to describe the effects of PCP and the combined application of PCP plus risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic with low affinity to dopamine (D2) receptors, or PCP plus haloperidol, a high affinity dopamine receptor antagonist, on the short term memory of rats. To this end, we have used the holeboard learning paradigm as a test for schizophrenia-like cognitive function (File & Pellow, 1985; Fletcher & Starr, 1985; Galey & Jaffard, 1992; Lister, 1987). The use of a classical and an atypical antipsychotic is related to the findings that haloperidol fails to restore sensomotoric deficits in rats (Swerdlow et al., 1996), whereas atypical antipsychotics, such as clozapine, prevent such deficits (Bakshi et al., 1994). As in our previous studies, we compared the pulsatile subchronic PCP treatment with the effects of continuously applied PCP (Schroeder et al., 1998). Additionally, using the parvalbumin technique we quantified morphologically a subpopulation of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampal formation. In order to find out whether transmitter binding sites as a marker of synaptic activity may be altered by PCP treatment binding assay and Western blot of glutamate and dopamine receptors were carried out.

Methods

All procedures were approved by the animal experimentation committee, according to the requirements of the National Act on the Use of Experimental Animals (Germany).

Animals

Experiments were carried out with male Lister rats (Harlan Winkelmann GmbH, Borchen, Germany) which were 7 weeks old at the beginning of the experiments. The animals were kept under controlled laboratory conditions (12 h light:dark cycle; light on: at 07:00 h; temperature 20±2°C; air humidity 55–60%), with water available ad libitum. The animals were food deprived to 80% of their body weight (i.e. 17 g food Altromin 1326 per animal per day) from the beginning of the PCP treatment until the day of exposure to the holeboard. Therefore, the animals were food deprived for 6 days. The animals were tested during the 'light-on' phase.

PCP and neuroleptic treatment

Animals were anaesthetized with etomidat (20 mg kg−1) and a PCP (Sigma, Germany) containing or an unloaded ethylenevinyl acetate copolymer (2 mm in diameter and about 10 mm in length) was implanted subcutaneously through a small incision between the fore- and hindlimbs of the rats. The implant is known to release PCP continuously (Haik-Creguer et al., 1998). PCP was applied in a dose of 5.0 mg kg−1 body weight per day (for details see Schroeder et al., 1998). All animals also received daily injections as well as implantation of polymers. For the neuroleptic treatment 0.1 mg kg−1 risperidone (RBI, U.S.A.) or 0.5 mg kg−1 haloperidol (Jansen-Cilag GmbH, Germany) were used as a daily injection over 5 days in parallel to the PCP treatment. The following experimental design was used:

Risperidone study:

daily NaCl/NaCl injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=8)

daily NaCl/risperidone injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=7)

daily PCP/NaCl injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=7)

daily PCP/risperidone injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=8)

daily NaCl/NaCl injection+PCP loaded polymer implantation (n=7)

daily NaCl/risperidone injection+PCP loaded polymer implantation (n=7)

Haloperidol study:

daily NaCl/NaCl injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=7)

daily NaCl/haloperidol injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=10)

daily PCP/NaCl injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=9)

daily PCP/haloperidol injection+unloaded control polymer implantation (n=9)

daily NaCl/NaCl injection+PCP loaded polymer implantation (n=9)

daily NaCl/haloperidol injection+PCP loaded polymer implantation (n=10)

The animals were anaesthetized on day 5 of the PCP treatment with etomidat (20 mg kg−1) and the polymers were then removed. Twenty-four hours later the holeboard learning was tested. Due to the short half-time of etomidat the animals were completely recovered. In the case of the 15 min and 1 h test the polymers were not removed.

Holeboard learning

Three days before testing the animals were allowed to habituate to the holeboard every day for 5 min and 24 h after the last PCP application the animals were tested in the holeboard according to the method used by Galey & Jaffard (1992): The holeboard (46×46 cm) contains four holes and the animals were placed in the middle of the holeboard. During the two acquisition phases small, purified casein based pellets (Bilaney Consultants/Germany) were located in one of the four holes. The acquisition phases lasted for 2 min and there was a break between both acquisition phases of 3 min. Five minutes thereafter, the retention was evaluated by recording the number of 'visited holes' which had contained food during the acquisition.

Binding assay

Four animals per group were decapitated; hippocampi, striata, nucleus accumbens and frontal cortices were dissected out and crude synaptic membrane fractions were prepared.

[3H]-L-glutamate (50 nM, specific activity: 1.43 Tbq mmol−1, NEN-Dupont) binding was assayed in membrane fractions prepared from brain regions of saline and PCP-treated rats as described by Schroeder et al. (1998). For the binding assay the membranes were incubated in 30 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2.5 mM CaCl2 for 40 min at 37°C. The non-specific binding was determined by addition of 100 μM unlabelled L-glutamate to parallel probes.

The 3H-L-SCH 23390 and 3H-spiroperidol binding was measured using an assay described by Köhler et al. (1994). A crude synaptic membrane suspension was incubated with 30 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0, containing (mM): NaCl 120, KCl 5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1 and 3H-SCH 23390 (specific activity: 1.43 Tbq mmol−1, NEN-Dupont, U.S.A.) or 3H-spiroperidol (specific activity: 800 GBq mmol−1, NEN-Dupont, U.S.A.) for 40 and 30 min at 37°C, respectively. All assays were performed at least in duplicates. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting non-specific binding–defined as that seen in the presence of 0.5 nM 3H-SCH 23390 or 1 nM 3H-spiroperidol plus 1 μM unlabelled cis-flupenthixol or 2 μM d-butaclamol (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany)–from total binding obtained with 3H-SCH 23390 or 3H-spiroperidol alone.

The reaction was terminated by rapid filtration under reduced pressure through GF 10 glass-fibre filters using an Inotech harvester (Berthold, Germany). Filters were washed with buffer and taken for liquid scintillation counting. The data were calculated as fmol bound radioligand per mg protein. Protein content was estimated in aliquots of membrane fraction using the technique by Lowry et al. (1951).

Under these conditions, binding of 3H-L-glutamate to hippocampal and 3H-SCH 23390 or 3H-spiroperidol to crude synaptic membranes from control rats appeared to be specific and kinetic studies suggested the existence of a single affinity state (Schroeder et al., 1998; Köhler et al., 1994).

Western blot

The dissected brain regions of saline and PCP treated rats were homogenized in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4, 0.5 NaCl, protease inhibitor cocktail) and centrifuged for 60 min at 100,000×g. The resulting pellet was resuspended and solubilized in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0, 0.25 M Tris, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 3 mM EGTA). Aliquots (10 μg protein amount) were subjected to 5–20% gradient SDS–PAGE and blotted on nitrocellulose membranes which were then incubated with the following antibodies of the glutamate receptor subtypes; anti-NMDAR1 (1 : 500), anti-GluR2 (1 : 200), anti-mGluR1 (1 : 250) and anti-GluR5-7 (1 : 200) antibodies from Pharmingen, Germany. The blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence kits (Amersham Buchler, Germany).

Parvalbumin staining

Four animals from each group were used for histological studies. Animals were deeply anaesthetized 24 h after the last PCP application with pentobarbital (40 mg kg−1) and transcardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl for 3 min, followed by 0.2 M phosphate buffer solution containing 30% saturated picrinic acid and 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were postfixed overnight in a buffered 20% sucrose solution and then cut in 40 μm horizontal sections using a cryostat. Sections were labelled using a monoclonal antibody against the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin as described by Kiss et al. (1996). Briefly, after washing the sections with 0.1 M Tris-buffer they were incubated with the first antibody parvalbumin (Swant, Switzerland) for 3 days at 4°C. Thereafter, the slides were washed and incubated with the second antibody for 90 min at room temperature followed by an avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain, ABC-Kit; Linaris/Germany). The sections were stained with DAB (diamino benzidin, Sigma/Germany) and then embedded in Entellan (Merck, Germany).

For counting, five sections per animal were sampled for parvalbumin staining. The parvalbumin positive cells were counted within the CA3 of the ventral hippocampus formation and within the dentate gyrus.

Data analysis and statistics

The calculations were carried out by STATISTICA software. Data were analysed for significance by the one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc LSD test (significance level P<0.05).

Results

Holeboard learning

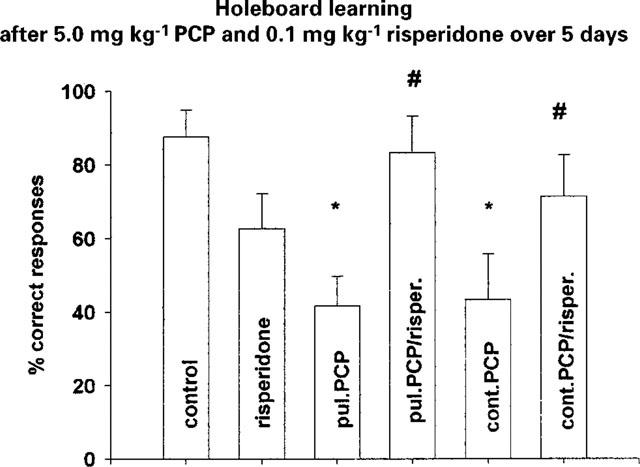

Irrespective of how PCP was given (pulsatile vs continuously) subchronic PCP led to an impairment in holeboard learning compared to the controls. Holeboard learning was tested 24 h after discounting the last PCP injection or the removal of the polymers, respectively (Figure 1). Because learning deficits became apparent only 24 h after PCP withdrawal 15 min or 1 h after the last PCP injection the animals were tested for short term memory deficits. Fifteen minutes after PCP withdrawal, animals were unable to learn the task which may be due to the acute PCP effect on dopaminergic transmitter system and reflected by direct ataxic effects. The correct responses (means) for the 1 h were: 63.6% for controls; 55.8% for PCP-implanted animals and 46.3% for PCP-injected animals indicating no modification (F(2,22)=0.9590; n.s.) in short term memory when PCP-treated animals and controls were compared.

Figure 1.

Holeboard learning after combined application of 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP and 0.1 mg kg−1 risperidone over 5 days (last application 24 h before testing) (means±s.e.mean; *P<0.05 vs control, #P<0.05 vs PCP respectively). Control n=8; risperidone n=7; pul. PCP n=7 (pulsatile PCP); pul. PCP/risper. n=8 (pulsatile PCP/risperidone); cont. PCP n=7 (continuous PCP); cont. PCP/risper. n=7 (continuous PCP/risperidone).

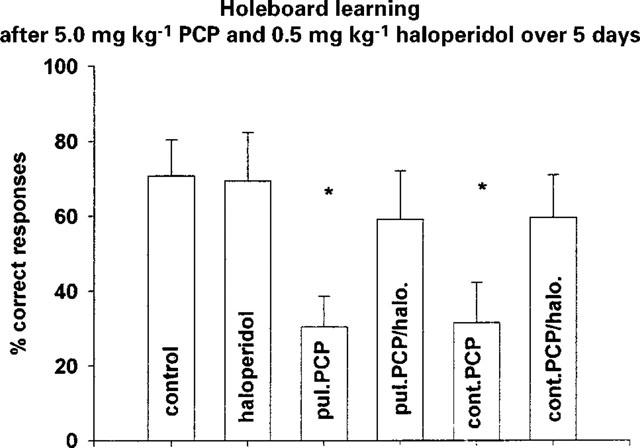

The combined application of 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP and 0.1 mg kg−1 risperidone over 5 days significantly reduced F(5,28)=2.942; P<0.02 the PCP induced deficit in short term memory (Figure 1). Also the classical neuroleptic, haloperidol, showed a tendency to antagonize the PCP-induced deficits (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Holeboard learning after combined application of 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP and 0.5 mg kg−1 haloperidol over 5 days (last application 24 h before testing) (means±s.e.mean; *P<0.05 vs control). Control n=7; haloperidol n=10; pul. PCP n=9 (pulsatile PCP); pul. PCP/halo. n=9 (pulsatile PCP/haloperidol); cont. PCP n=9 (continuous PCP); cont. PCP/halo. n=10 (continuous PCP/haloperidol).

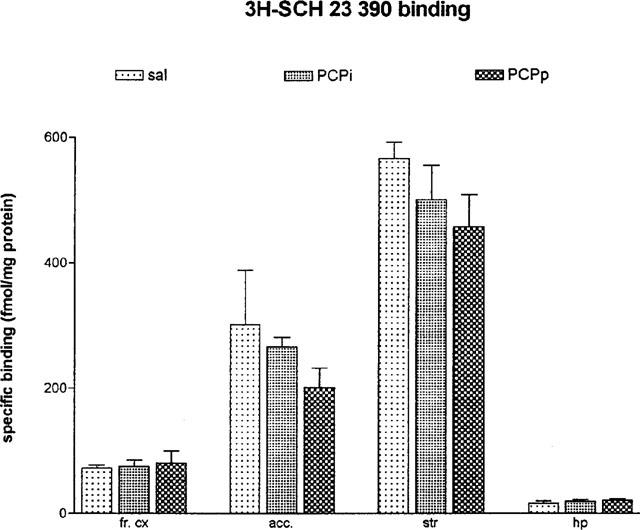

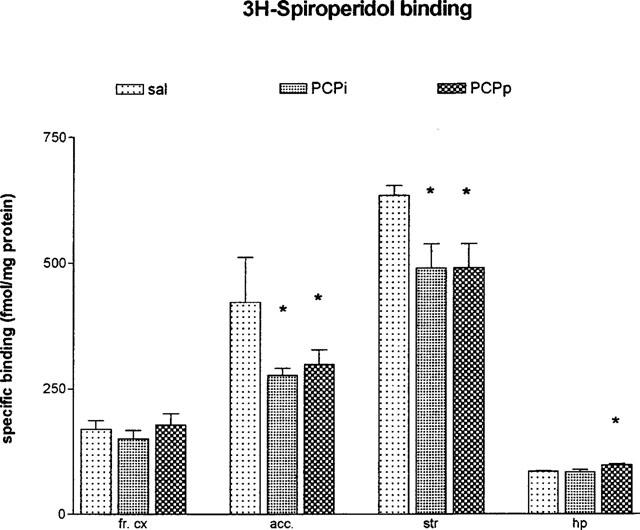

Binding assay

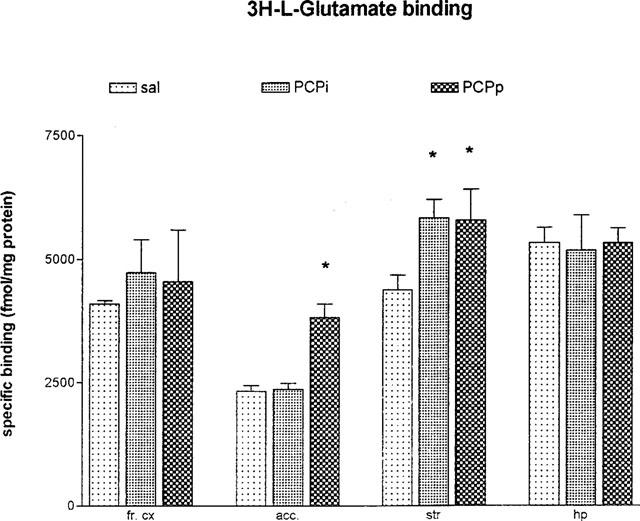

Using ligand concentration of 0.5 nM, the specific 3H-SCH 23390 binding for the D1 receptor was not changed in frontal cortex, striatum, hippocampus and nucleus accumbens (Figure 3). Concerning the D2 receptor binding sites we demonstrated a downregulation of these binding sites in striatum F(2,6)=8.286; P<0.05 and in nucleus accumbens F(2,8)=5.2847; P<0.05 after pulsatile as well as after continuously applied PCP. In contrast we could detect a 15% upregulation of the D2 binding sites after continuously applied PCP in hippocampus F(2,9)=4.454; P<0.05 (Figure 4). The overall 3H-glutamate binding sites increased after both PCP treatment in striatum F(2,7)=5.847; P<0.05 and also after continuously applied PCP in nucleus accumbens F(2,7)=22.057; P<0.05 (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Specific 3H-SCH 23390 binding in frontal cortex (fr. cx), nucleus accumbens (acc.), striatum (str) and hippocampus (hp) after 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP over 5 days (24 h after the last PCP application; means±s.e.mean; in fmol mg−1 protein). sal=daily saline injection+control polymer (n=4); PCPi=daily 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP injection+control polymer (n=4); PCPp=daily saline injection+PCP-loaded polymer (n=4).

Figure 4.

Specific 3H-spiroperidol binding in frontal cortex (fr. cx), nucleus accumbens (acc.), striatum (str) and hippocampus (hp) after 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP over 5 days (24 h after the last PCP application; means±s.e.mean; in fmol mg−1 protein) *P<0.05 vs control animals. sal=daily saline injection+control polymer (n=4); PCPi=daily 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP injection+control polymer (n=4); PCPp=daily saline injection+PCP-loaded polymer (n=4).

Figure 5.

Specific 3H-L-glutamate binding in frontal cortex (fr. cx), nucleus accumbens (acc.), striatum (str) and hippocampus (hp) after 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP over 5 days (24 h after the last PCP application; means±s.e.mean; in fmol mg−1 protein) *P<0.05 vs control animals. sal=daily saline injection+control polymer (n=4); PCPi=daily 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP injection+control polymer (n=4); PCPp=daily saline injection+PCP-loaded polymer (n=4).

The determination of the expression of glutamate receptor proteins (NMDAR1, mGluR1, GluR2, GluR5/7) after PCP did not show any modification in the blots (data not shown). This suggests that the altered binding of D2 and glutamate receptors is realized by changes of the existing receptors (e.g. masked or unmasked receptors).

Parvalbumin staining

Rats having received 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP injection or implantation of PCP loaded polymers releasing the same dose over 5 days revealed a significant F(2,57)=21.2542; P<0.01 decrease in the number of parvalbumin immunoreactive cells within the CA3 of the hippocampus. There were no significant differences of the number of parvalbumin positive cells within the dentate gyrus (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Number of parvalbumin positive cells in CA3 and dentate gyrus after 5.0 mg kg−1 PCP over 5 days (means±s.e.mean; *P<0.05 vs NaCl).

Discussion

The postulated dysfunction of the glutamatergic transmission system in schizophrenia suggested by NMDA receptor hypofunction or glutamate deficiency theories (Grace, 1991; Olney & Farber, 1995) has been discussed in connection with the traditional dopamine hyperfunction theory on the basis of glutamate-dopamine interaction (Carlsson & Carlsson, 1990; Starr, 1995). The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia was derived from studies of PCP-induced psychosis in healthy subjects which displayed negative and positive schizophrenia-like symptoms.

The main findings of the present study can be summarized as follows first: independent of the mode of application (daily pulsatile injection vs continuously released PCP from subcutaneously implanted polymers), subchronic PCP produces short-term memory deficits in the holeboard learning task. Second: this impairment can be restored completely by the atypical neuroleptic risperidone but only partially by haloperidol when given simultaneously. Holeboard learning can be taken into consideration to investigate the action of neuroleptics and supports the relevance of the subchronic PCP model of schizophrenia-like behaviour in rats. Furthermore, the impaired short term memory capacity induced by PCP simulates cognitive dysfunctions. The determination of spatial learning after PCP injection in dentate gyrus led to a disruption of long-term memory but not to short-term memory loss (Kesner & Dakis, 1995). When PCP is applied at higher doses, the dopaminergic, serotonergic and cholinergic transmitter systems are altered as well (Hyde, 1992). From our behavioural data we can not decide which specific transmitter system was modified by PCP treatment. The effect of haloperidol, however, indicates that the dopaminergic system may have been altered. In contrast, the complete reversal of memory deficits by risperidone which affects dopaminergic as well as serotonergic and cholinergic neurons, indicates complex changes of transmission systems after PCP treatment. Systemic PCP application is known to increase extracellular 5-HT levels and has low micromolar affinity for the 5-HT reuptake site (Martin et al., 1998). Our results are supported by findings of Sams-Dodd (1995; 1996; 1997; 1998a,1998b,1998c) who described a reduction of the level of PCP-induced stereotyped behaviour and an improvement of PCP-induced social isolation by novel antipsychotic drugs such as risperidone or olanzepine.

Previously, we found a downregulation of PCP binding sites in the hippocampus and the striatum after the same regime of PCP treatment (Schroeder et al., 1998). In contrast, in the present study the total, un-differentiated glutamate binding to striatal and nucleus accumbens crude membranes was upregulated in response to PCP treatment. An increased glutamatergic transmission via non-NMDA glutamate receptors after PCP has been described by Adams & Moghaddam (1998). Therefore, it can be postulated that after a subchronic NMDA receptor blockade the PCP binding sites were downregulated whereas the other glutamate receptor subtypes (i.e. AMPA, mGluR) were upregulated as a compensatory response to NMDA receptor inhibition by PCP. Furthermore, regional differences in the effect of PCP may exist which were not determined here.

Interestingly, we found a decreased D2-mediated dopaminergic activity in the striatum and nucleus accumbens as measured by binding assay. Jentsch et al. (1997b) described a dopaminergic hyperactivity in frontal cortical regions and nucleus accumbens of rats and monkeys after acute PCP treatment, whereas repeated PCP applications were followed by a decreased dopaminergic activity supporting our data. Thus, it seems that cognitive dysfunction is associated with reduced dopaminergic activity after subchronic PCP treatment (Jentsch & Roth, 1999). It has to be noted, that these authors as well as others (Grace, 1991; Roberts et al., 1994) postulated a cortical dopaminergic hypoactivity in response to a subcortical dopaminergic hyperactivity. We did not find any changes in the dopaminergic activity at the receptor level in the frontal cortex of subchronically PCP-treated rats which is at variance with this proposal.

Our previous data indicate that rats treated subchronically by pulsatile PCP injections did not show deficits in latent inhibition, whereas rats given PCP continuously using implanted polymers were impaired in latent inhibition. We postulated that this simulates a cognitive dysfunction characteristic for attentional deficits described for certain forms of schizophrenia (Schroeder et al., 1998). In contrast, for the impaired short-term memory the mode of PCP application did not play a role which suggests that plasma fluctuation of PCP has no influence on holeboard learning.

In morphological studies the loss of parvalbumin-positive cells in the hippocampal CA3 subregion was detectable after both pulsatile and continuous PCP administration. Altered activity of GABAergic interneurons receiving excitatory innervation from glutamatergic neurons can modulate mechanisms of long-term plasticity such as LTP (long-term potentiation), LTD (long-term depression) and learning and memory (McBain et al., 1999). Therefore, the described loss of GABAergic interneurons after PCP treatment seems to be an indicator for the deficits in short-term memory measured by holeboard learning. Neurodegenerative damage with cell death (Ellison, 1995) are a consequence of chronic administration of PCP. These neurodegenerative processes were discussed as a neural substrate for the cognitive dysfunction (Wozniak et al., 1996; Corso et al., 1997). Furthermore, according to Olney's NMDA receptor hypofunction hypothesis the inhibition of NMDA receptors by PCP is accompanied by a dysinhibition of GABAergic interneurons (Olney & Farber, 1995) resulting in alteration of these interneurons found in the CA3 of the hippocampal formation.

In summary it can be concluded that after subchronic, continuously applied PCP in rats the glutamatergic system as well as the dopaminergic system are modified, both documented by morphological and neurochemical changes which may underly the PCP-induced psychosis-like behavioural responses in adult rats. We propose that these changes underly the PCP-induced psychosis-like short-term memory deficits in adult rats and, therefore, the chronic PCP application in combination with the holeboard test not only serves as a useful tool to simulate schizophrenia-like symptoms in rats, but is also a useful tool to evaluate antischizophrenic action of drugs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs A. Schulze, I. Schwarz and U. Werner for their excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 426/TP C3.

Abbreviations

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PCP

phencyclidine

References

- ADAMS B., MOGHADDAM B. Corticolimbic dopamine neurotransmission is temporally dissociated from the cognitive and locomotor effects of phencyclidine. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:5545–5554. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05545.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AKBARIAN S., KIM J.J., POTKIN S.G., HAGMAN J.O., TAFAZZOLI A., BUNNEY W.E., JR, JONES E.G. Gene expression for glutamic acid decarboxylase is reduced without loss of neurons of prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 1995;52:258–266. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950160008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKSHI V.P., SWERDLOW N.R., GEYER M.A. Clozapine antagonizes phencyclidine-induced deficits in sensorimotor gating of the startle response. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:787–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENES F.M., MCSPARREN J., BIRD E.D., SAN GIOVANNI J.P., VINCENT S.L. Deficits in small interneurons in prefrontal cortex and cingulate cortices of schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 1991;48:996–1001. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810350036005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOGERTS B. The temperolimbic system of positive schizophrenic symptoms. Schiz. Bull. 1997;23:423–435. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARLSSON M., CARLSSON A. Interactions between the glutamatergic and monoaminergic systems within the basal ganglia–implications for schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:272–276. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90108-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORSO T.D., SESMA M.A, , TENKOVA T.I., DER T.C., WOZNIAK D.F., FARBER N.B., OLNEY J.W. Multifocal brain damage induced by phencyclidine is augmented by pilocarpine. Brain. Res. 1997;752:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COYLE J.T. The glutamatergic dysfunction hypothesis for schizophrenia. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 1996;2:241–253. doi: 10.3109/10673229609017192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLISON G. The NMDA antagonists phencyclidine, ketamine and dizocilpine as both behavioral and anatomical models of the dementias. Brain Res. Rev. 1995;20:250–267. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00014-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAUMAN B.J., FAUMAN M.A. Chronic phencyclidine (PCP) abuse: a psychiatric perspective-part II: psychosis. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1980;16:72–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FILE S.E., PELLOW S. The effects of trazolobenzodiazepines in two animal tests of anxiety and in the holeboard. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;86:729–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb08952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLETCHER G.H., STARR M.S. SKF 38393 and apomorphine modify locomotion and exploration in rats placed on a holeboard by separate actions at dopamine D-1 and D-2 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985;117:381–385. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALEY D., JAFFARD R. Post-training medial septal stimulation improves spatial information processing in BALB/c mice. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;143:87–90. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDBERG T.E., GOLD J.M.Neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia Schizophrenia 1995Blackwell: London; 146–162.In: Hirsch, S.R. & Weinberger, D.R. (eds) [Google Scholar]

- GOLDMAN-RAKIC P.S.Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia: Relevance of working memory Psychopathology and the brain 1991Raven: New York; 1–23.Carroll, B.J. & Barrett, J.E. (eds) [Google Scholar]

- GRACE A.A. Phasic versus tonic dopamine release and the modulation of dopamine system in responsitivity: a hypothesis for the etiology of schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 1991;41:1–24. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90196-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAIK-CREGUER K.L., DUNBAR G.L., SABEL B.A., SCHROEDER U. Small drug sample fabrication of controlled release polymers using the microextrusion method. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1998;80:37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HYDE J.F. Effects of phencyclidine on 5-hydroxytryptophan- and suckling-induced prolactin release. Brain Res. 1992;573:204–208. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90764-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENTSCH J.D., REDMOND D.E., JR, ELSWORTH J.D., TAYLOR J.R., YOUNGREN K.D., ROTH R.H. Enduring cognitive deficits and cortical dopamine dysfunction in monkeys after long-term administration of phencyclidine. Science. 1997a;277:953–955. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENTSCH J.D., ROTH R.H. The neuropsychopharmacology of phencyclidine: from NMDA receptor hypofunction to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:201–225. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENTSCH J.D., TRAN A., LE D., YOUNGREN K.D., ROTH R.H. Subchronic phencyclidine administration reduces mesoprefrontal dopamine utilization and impairs prefrontal cortical-dependent cognition in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997b;17:92–99. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES K.W., BAUERLE L.M., DENOBLE V.J. Differential effects of sigma and phencyclidine receptor ligands on learning. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;179:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90406-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESNER R.P., DAKIS M. Phencyclidine disrupts acquisition and retention performance within a spatial continuous recognition memory task. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1993;44:419–424. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90484-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESNER R.P., DAKIS M. Phencyclidine injections into the dorsal hippocampus disrupt long- but not short-term memory within a spatial learning task. Psychopharmacology. 1995;120:203–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02246194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KISS J., BUZSAKI G., MORROW J.S., GLANTZ S.B., LERANTH C. Entorhinal cortical innervation of parvalbumin-containing neurons (basket and chandelier cells) in the rat ammon's horn. Hippocampus. 1996;6:239–246. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:3<239::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KÖHLER U., SCHRÖDER H., AUGUSTIN W., SABEL B.A. A new animal model of dopamine supersensitivity using s.c. implantation of haloperidol releasing polymers. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;170:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRYSTAL J.H., KARPER L.P., SEIBYL J.P., FREEMAN G.K., DELANEY R., BREMNER J.D., HENINGER G.R., BOWERS M.B., JR, CHARNEY D.S. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist, ketamine, in humans: Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LISTER R.G. Interactions of Ro 15-4513 with diazepam, sodium pentobartibal and ethanol in a holeboard test. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1987;28:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O.H., ROSENBROUGH A.L., FARR A.L., RANDALL R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN P., CARLSSON M.L., HJORTH S. Systemic PCP treatment elevates brain extracellular 5-HT: A microdialysis study in awake rats. NeuroReport. 1998;13:2985–2988. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199809140-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCBAIN C.J., FREUND T.F., MODY I. Glutamatergic synapses onto hippocampal interneurons: precision timing without lasting plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:228–235. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY T.K., RIDLEY R.M. The effect of dizocilpine (MK-801) on conditional discrimination learning in the rat. Behav. Pharmacol. 1997;8:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLNEY J.W., FARBER N.B. NMDA antagonists as neurotherapeutic drugs, psychotogens, neurotoxins, and research tools for studying schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13:335–345. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00079-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLNEY J.W., FARBER N.B. Discussion of Bogerts' temporolimbic system theory of paranoid schizophrenia. Schiz. Bull. 1997;23:533–535. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLNEY J.W., LABRUYERE J., PRICE M.T. Pathological changes induced in cerebrocortical neurons by phencyclidine and related drugs. Science. 1989;244:1360–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.2660263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARLSON G.D. Psychiatric and medical syndromes associated with phencyclidine (PCP) abuse. J. Hopkins Med. J. 1981;148:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS A.C., DESALVIA M.A., WILKINSON L.S., COLLINS P., MUIR J.L., EUERI H.B.J., ROBBINS T.W. 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the prefrontal cortex in monkeys enhance performance on an analog of the Wisconsin Card Sort Test: Possible interactions with subcortical dopamine. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:2531–2544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02531.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMS-DODD F. Automation of the social interaction test by a video-tracking system: behavioural effects of repeated phencyclidine treatment. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1995;59:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00173-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMS-DODD F. Phencyclidine-induced stereotyped behavior and social isolation in rats: a possible animal model of schizophrenia. Behav. Pharmacol. 1996;7:3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMS-DODD F. Effect of novel antipsychotic drugs on phencyclidine-induced stereotyped behaviour and social isolation in the rat social interaction test. Behav. Pharmacol. 1997;8:196–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMS-DODD F. A test predictive validity of animal models of schizophrenia based on phencyclidine and D-amphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998a;18:293–304. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMS-DODD F. Effects of continuous D-amphetamine and phencyclidine administration on social behaviour, stereotyped behaviour, and locomotor activity in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998b;19:18–25. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMS-DODD F. Effects of dopamine agonists and antagonists on PCP-induced stereotyped behaviour and social isolation in the rat social interaction test. Psychopharmacology. 1998c;135:182–193. doi: 10.1007/s002130050500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHROEDER U., SCHROEDER H., DARIUS J., GRECKSCH G., SABEL B.A. Simulation of psychosis by continuous delivery of phencyclidine from controlled-release polymer implants. Behav. Brain Res. 1998;97:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STARR M.S. Glutamate/dopamine D1/D2 balance in the basal ganglia and its relevance to Parkinson's disease. Synapse. 1995;19:264–293. doi: 10.1002/syn.890190405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWERDLOW N.R, , BAKSHI V.P., GEYER M.A. Seroquel restores sensorimotor gating in phencyclidine-treated rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:1290–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMMINGA C.A., KANEDA H., BUCHANAN R., KIRKPATRICK K., THAKER G.K., YABLONSKI M.B., HOLCOMB H.H.The limbic system in schizophrenia: Pharmacologic and metabolic evidence Advances in Neuropsychiatry and Psychopharmacology, Vol. I: Schizophrenia research 1991Raven Press Ltd.: New York; 99–109.Tamminga, C.A. & Schulz, S.C. (eds) [Google Scholar]

- TAMMINGA C.A., TANIMOTO K., KUO S., CHASE T.N., CONTRERAS P.C., JACKSON A.E., O'DONOHUE T.L. PCP-induced alterations in cerebral glucose utilization in rat brain: blockade by metaphit, a PCP-receptor-acylating agent. Synapse. 1987;1:497–504. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSAI G., PASSANI L.A., SLUSHER B.S., CARTER R., BAER L., KLEINMAN J.E., COYLE J.T. Abnormal excitatory neurotransmitter metabolism in schizophrenic brains. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1995;52:829–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950220039008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOZNIAK D.F., BROSNON-WATTERS G., NARDI A., MCEWEN M., CORSO T.D., OLNEY J.W., FIX A.S. MK-801 neurotoxicity in male mice: Histologic effects and chronic impairments in spatial learning. Brain Res. 1996;707:165–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]