Abstract

Intravenously injected cisplatin at a dose of 4 mg kg−1 induced early and delayed emesis in all pigeons without occurrence of lethality during a 72 h observation period. The early emetic response occurred with a latency of 81.3±8.0 min (n=15) and reached a peak at 2–3 h, and decreased gradually within 8 h after injection. Then the delayed emetic response, whose peak was found between 10 to 23 h, lasted up to 48 h. The emetic response markedly declined after 48 h.

Reserpine markedly reduced monoamine levels in both brain and intestine and completely abolished the early and delayed emesis. Dexamethasone markedly reduced not only the early but also the delayed emetic responses. p-Chlorophenylalanine decreased the level of serotonin in brain and intestine without affecting noradrenaline and dopamine and partly reduced the early emetic response, but did not affect delayed emesis.

Bilateral vagotomy prolonged the latency time to the onset of early emesis, and reduced the emetic responses in both the early and delayed phases.

The above results suggest that the cisplatin-induced early emesis in the pigeon is partially mediated via the vagal nerve and reserpine-sensitive monoaminergic systems including the serotonergic system; the delayed emesis is associated with monoaminergic but not the serotonergic systems.

Keywords: Cisplatin, delayed emesis, pigeons, serotonin

Introduction

Nausea and emesis are important factors that reduce drug compliance in patients receiving anticancer chemotherapeutic drugs such as cisplatin (Laszlo & Lucas, 1981; Laszlo, 1983). In humans, it is well known cisplatin induces early and delayed emesis. The early emesis which starts 1 to 3 h after cisplatin administration, is prevented with 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists such as ondansetron and granisetron (Cubeddu et al., 1990; Ruff et al., 1994). However, the delayed emesis, which begins 17 to 24 h after cisplatin administration and lasts for several days (Kris et al., 1985; Rittenberg et al., 1995), has proven more resistant to antiemetic therapy with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (De Mulder et al., 1990; Marty et al., 1990; Gandara, 1991; Gandara et al., 1993).

A number of animal studies on cisplatin-induced early-phase emesis within 8 h have been reported using dogs (Gylys et al., 1979; Lelieveld et al., 1987; Cohen et al., 1989), cats (London et al., 1979; McCarthy & Borison, 1984; Smith et al., 1988), ferrets (Florczyk et al., 1982; Costall et al., 1986; 1987), suncus murinus (Matsuki et al., 1988; Torii et al., 1991) and pigeons (Preziosi et al., 1992). These studies suggested the important role of 5-HT in cisplatin-induced early emesis in many species. In addition, the cisplatin-induced early emetic response was completely or partially reduced by vagotomy in suncus murinus (Mutoh et al., 1992) and ferrets (Hawthorn et al., 1988), respectively. On the contrary, animal studies on cisplatin-induced delayed-phase emesis have only been carried out in ferrets (Rudd & Naylor, 1994; Rudd et al., 1994; 1996) and piglets (Milano et al., 1995; Grélot et al., 1996), and the delayed emetic pathogenesis has not been clarified.

We investigate whether pigeons might be suitable for studying the drug-induced emetic response. In preliminarily experiments we observed that cisplatin dose-dependently induced emesis in the pigeon, and intravenously injected cisplatin at a dose of 4 mg kg−1 induced early and delayed emesis in all pigeons used without occurrence of lethality during a 72 h observation period. In the present study, we have investigated the profiles of cisplatin (4 mg kg−1, i.v.)-induced early and delayed emesis in the pigeon. The participation of monoamines in the cisplatin-induced emesis in the pigeon was studied by using reserpine and p-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA) as a monoamine depletor and an inhibitor of tryptophan hydroxylase (Koe & Weissman, 1966), respectively. Reserpine and PCPA were reported to reduce cisplatin-induced early-phase emesis in ferrets (Barnes et al., 1988). In addition, the antiemetic effects of bilateral vagotomy and dexamethasone were examined. The role of afferent vagus nerve in cisplatin-induced early emesis has been confirmed in suncus murinus (Mutoh et al., 1992), in dogs (Ito et al., 1987; Fukui et al., 1992) and in ferrets (Hawthorn et al., 1988; Andrews et al., 1990), and dexamethasone has antiemetic effects against cisplatin-induced early and delayed emesis in ferrets (Rudd et al., 1996).

Methods

Animals

Adult pigeons of either sex weighing between 350 and 550 g (Saitama Experimental Animals Supply Co., Japan) were used. All pigeons were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle, and standard pigeon chow and water were available ad libitum. All animal experimental procedures were carried out under the Guidelines for Animal Experiments, Toho University School of Medicine.

Cisplatin-induced emesis

The pigeons were placed in individual cages, and cisplatin (4 mg kg−1) was administered intravenously via the brachial wing vein. The behaviour of the pigeons was observed with a video-monitoring system for up to 48 or 72 h under unrestricted conditions. During the observation period, food and water were available ad libitum. Each pigeon was used once. Vomiting and retching associated with and without oral expulsion, respectively, were considered as the emetic response (Preziosi et al., 1992). The emetic responses were characterized by a bout of emesis and there was more than an emetic behaviour within one bout. The latency time to first emesis, the number of bouts of emesis and the total number of emetic behaviours were recorded. The antiemetic effects of a monoamine depletor (reserpine), a 5-HT synthesis inhibitor (PCPA), dexamethasone and bilateral vagotomy were studied. Reserpine (1 mg kg−1, showing the marked reduction of monoamines such as 5-HT and catecholamines in this study) was administered intramuscularly twice 48 and 24 h before cisplatin administration. PCPA (300 mg kg−1, Koe & Weissman, 1966) was administered intramuscularly once or consecutively administered for 5 days, and cisplatin was administered 72 or 24 h, respectively, after the last administration. Dexamethasone (1 mg kg−1, Rudd & Naylor, 1996) was administered intramuscularly four times at 1 h before and 8, 24 and 32 h after cisplatin administration.

Bilateral vagotomy

The pigeons were anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (30 mg kg−1, i.m.) and the bilateral vagotomies were carried out at cervical sites. The animals were administered benzylpenicillin (20,000 units kg−1, i.m., crystalline penicillin G potassium, Meiji, Japan) and gentamicin sulfate ointment (Gentacin® ointment, Schering-Plough, Japan) was applied to the sutural sites. The animals were allowed 1 week to recover from surgery.

Tissue sampling for monoamine determination

Three discrete parts of the brain (medulla oblongata, telencephalon and diencephalon plus mesencephalon) of the pigeons as well as the small intestine were used for monoamine determinations by which the effects of reserpine and PCPA on the monoamine levels were investigated. Pigeons were decapitated 24 h after the last dose of pretreatments with reserpine for 2 days or PCPA for 5 days, and 72 h after the single pretreatment with PCPA. After decapitation, the brains and small intestines were rapidly excised, and placed on an ice-cooled glass plate in a cold box (0°C). The small intestines were excised at a distance of 5–7 cm from the pylorus. The dissection of brain samples of the three parts was performed according to the atlas of Karten & Hodos (1967). After freezing the brain parts and intestine on dry ice, the pieces were weighed and stored at −80°C until required.

Determination of monoamines and their metabolites

Tissue samples were homogenized with an ultrasonic homogenizer in cold 0.2 M perchloric acid containing 0.1 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA·2Na) and the internal standard, (−) isoproterenol hydrochloride. After centrifugation for 15 min at 20,000×g (4°C), the supernatants were adjusted to pH 3.0 with 1 M sodium acetate solution. Monoamines and metabolites were determined using a high performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC, Eicom Corp., Japan) with electrochemical detection (ECD-300), a pump (EP-300) and an analytical column (Eicompac MA-5ODS). The mobile phase consisted of 85% 0.1 M sodium acetate·citric acid buffer, pH 3.3, containing 230 mg l−1 1-octanesulphonic acid sodium salt and 5 mg l−1 EDTA·2Na, and 15% methanol. The flow rate was maintained at 1.0 ml min−1. The standards used were (±) noradrenaline hydrochloride (NA), (±) normetanephrine hydrochloride (NM), dopamine hydrochloride (DA), homovanillic acid (HVA), 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), serotonin creatinine sulphate (5-HT) and 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid (5-HIAA). All standards were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (U.S.A.). The other reagents were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Ind. (Japan), except 1-octanesulphonic acid sodium salt (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Japan).

Drugs

Cisplatin [4 mg kg−1, cis-platinum (II) diamine dichloride, Sigma Chemical Co., U.S.A.] was dissolved in 0.9% saline solution at 65–70°C, followed by cooling to 45–50°C and administered immediately. Reserpine (Apoplon® Inj.) was purchased from Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co. (Japan). PCPA methyl ester hydrochloride and dexamethasone 21-phosphate disodium salt were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (U.S.A.) and dissolved in 0.9% saline solution. All drug solutions were prepared just before use. Doses are expressed as the free base.

Data analysis

Values presented are the mean±s.e.mean. The differences between means were evaluated for statistical significance using the one-way analysis of variance followed by either Dunnett's test or Tukey's multiple comparison test. Fisher's exact test was used for the statistical evaluation of the incidence of emesis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cisplatin-induced emesis in pigeons

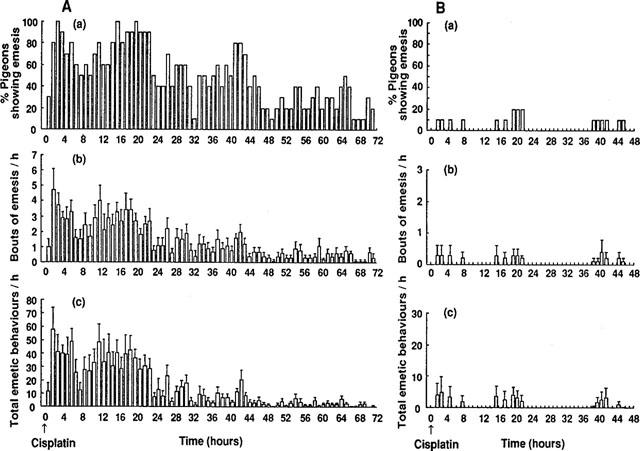

Intravenously injected cisplatin at a dose of 4 mg kg−1 induced emesis in all of the injected pigeons with a latency of 81.3±8.0 min (n=15). The emetic response reached a peak at 2–3 h, and decreased gradually within 8 h after injection. Then the second-phase emetic response whose peak was found between 10 to 23 h, lasted up to 72 h. The cisplatin-induced emetic response markedly declined after 48 h. None of the animals died during the 72 h observation period (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) The profile of cisplatin (4 mg kg−1, i.v.)-induced emetic response in pigeons during a 72 h observation period (n=15), and (B) effect of dexamethasone (1 mg kg−1, i.m., four times at 1 h before and 8, 24 and 32 h after cisplatin administration) on the cisplatin-induced emetic response during a 48 h observation period (n=10). Each hourly bin in figure (a) represents the percentage of pigeons showing emesis in 1 h time intervals after cisplatin administered at time zero. Each hourly bin with a vertical bar in figure (b) and (c) represents the mean±s.e.mean of the number of bouts of emesis and total number of emetic behaviours, respectively, occurring in 1 h time intervals.

In the present study, the emetic response within the first 8 h period was called early emesis, and the emetic response between 8 and 48 h, delayed emesis.

Effect of dexamethasone on cisplatin-induced emesis

Dexamethasone markedly reduced the cisplatin-induced early and delayed emetic responses during the 48 h observation period. Six out of ten pigeons treated with dexamethasone did not exhibit any emesis to cisplatin (Figure 1B).

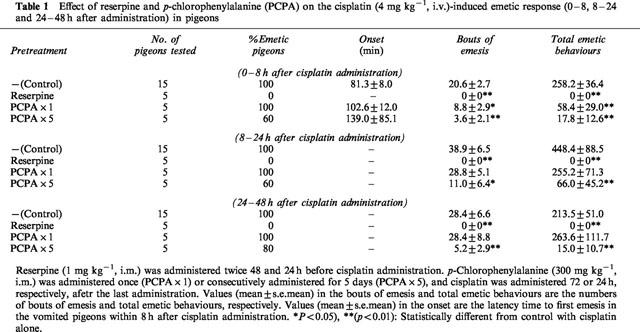

Effect of reserpine and PCPA on the cisplatin-induced emesis

Pretreatment with reserpine completely suppressed the cisplatin-induced emetic responses during the 48 h observation period. A single pretreatment with PCPA 72 h before cisplatin administration did not affect the incidence of emesis due to cisplatin, but significantly reduced the number of emetic responses but only within the first 8 h period. Pretreatment with PCPA for 5 days partially reduced the early emetic incidence of cisplatin and significantly reduced the number of emetic responses in both the early and delayed phases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of reserpine and p-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA) on the cisplatin (4 mg kg−1, i.v.)-induced emetic response (0–8, 8–24 and 24–48 h after administration) in pigeons

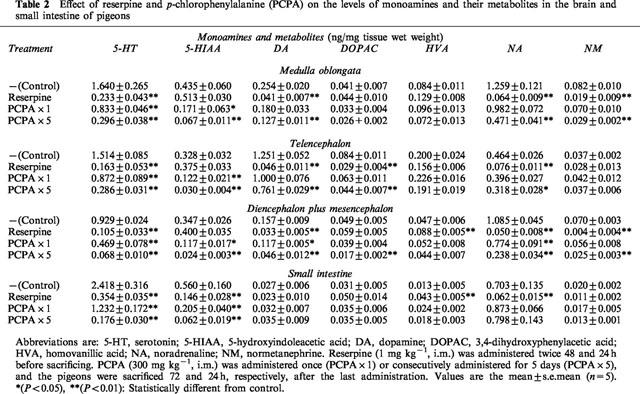

Effect of reserpine and PCPA on monoamine levels in the brain and intestine

Reserpine markedly reduced the levels of 5-HT, DA and NA in both brain and intestine. The level of 5-HIAA in the intestine, but not in the brain, was also reduced by the pretreatment with reserpine. A single pretreatment with PCPA significantly reduced the levels of 5-HT and 5-HIAA without affecting the levels of DA, NA and their metabolites (DOPAC, HVA and NM) in the brain and intestine of pigeons. Pretreatment with PCPA for 5 days caused a marked depletion of 5-HT and 5-HIAA in both brain and intestine, and significantly reduced DA, NA and their metabolites (DOPAC and NM) in the brain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of reserpine and p-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA) on the levels of monoamines and their metabolites in the brain and small intestine of pigeons

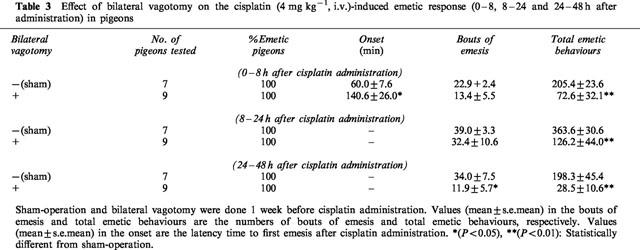

Effect of bilateral vagotomy on the cisplatin-induced emesis

Cisplatin-induced early and delayed emetic responses appeared in all of the vagotomized pigeons. But the latency to the first emesis and the number of emetic responses in both the early and delayed phases were significantly reduced by bilateral vagotomy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of bilateral vagotomy on the cisplatin (4 mg kg−1, i.v.)-induced emetic response (0–8, 8–24 and 24–48 h after administration) in pigeons

Discussion

Cisplatin-induced early and delayed emesis in the pigeon

In the pigeon, cisplatin-induced early emesis was previously shown by Preziosi et al. (1992), who observed emesis for up to 4 h after intravenous administration of cisplatin in a dose of 5 mg kg−1. However, our preliminary study indicated a 50% mortality of pigeons within 48 h after administration of 5 mg kg−1 of cisplatin (unpublished data). We therefore used a dose of 4 mg kg−1, i.v. of cisplatin, which induced early and delayed emesis in all pigeons studied without the occurrence of lethality during a 72 h observation period. No emesis was observed between 8 and 10 h after cisplatin in eight out of 15 control pigeons and a less intense crisis of emesis was observed in the other seven control pigeons. So, we determined that the transition from the early to delayed phases was identified between 8 and 10 h. The cisplatin-induced emetic response markedly decreased after 48 h in all of the control pigeons. From the above, the emetic responses within the first 8 h period and between 8 and 48 h after cisplatin administration were classified as early and delayed emesis, respectively. In a preliminary study, cisplatin (3 mg kg−1, i.v.) induced dual emesis in only six out of ten animals, and emesis did not occur between 6 and 15 h after cisplatin administration (unpublished data).

The time course of both the early and delayed phases of cisplatin-induced emesis in pigeons seems shorter than those observed in other species. The early phase is presumed to last for one day in humans (Kris et al., 1985) and ferrets (Rudd et al., 1994) and for the first 16 h in piglets (Milano et al., 1995).

Effects of reserpine and PCPA on the tissue monoamine levels and the cisplatin-induced emesis

The role of 5-HT in cisplatin-induced early emesis has been documented in humans and animals, and it has been reported that PCPA reduces acute cisplatin-induced emesis in humans (Alfieri & Cubeddu, 1995), ferrets (Barnes et al., 1988), dogs (Fukui et al., 1992) and pigeons (Preziosi et al., 1992). Reserpine is also reported to reduce cisplatin-induced early-phase emesis within 4 h in ferrets (Barnes et al., 1988). In the present study, pretreatment with reserpine markedly reduced the levels of monoamines including 5-HT in both brain and intestine, and abolished the early and delayed emesis induced by cisplatin during the 48 h observation period. A single pretreatment with 300 mg kg−1, i.m. of PCPA, which decreased the levels of 5-HT and 5-HIAA in brain and intestine without affecting the levels of NA and DA, only partly reduced the number of early emetic responses within the first 8 h period. The single pretreatment with PCPA neither reduced the emetic incidence within the first 8 h period, nor affected the delayed emesis. A pretreatment with PCPA for 5 days caused a similar reduction in the levels of 5-HT in brain and intestine as was caused by reserpine, but did not completely reduce the cisplatin-induced early and delayed emetic responses. The pretreatment with PCPA for 5 days also reduced the levels of other monoamines (NA and DA) in brain and intestine, but the reduction was smaller than that produced by pretreatment with reserpine. The antiemetic effects of reserpine and PCPA indicate that the cisplatin-induced early emesis in pigeons is associated with reserpine-sensitive monoaminergic systems including the 5-HT system, and the delayed emesis is associated with monoaminergic systems excluding the serotonergic system.

Cisplatin-induced early emesis should be prevented with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists as observed in humans (Cubeddu et al., 1990; Ruff et al., 1994), ferrets (Costall et al., 1987), cats (Lucot, 1989), suncus murinus (Torii et al., 1991) and piglets (Milano et al., 1995). However, in pigeons, we could not observe the antiemetic activity of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as granisetron, since indolic 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have intrinsic emetic activity in pigeons (Preziosi et al., 1992). Actually we preliminarily observed that granisetron (0.3 mg kg−1, i.m.) produced emetic responses in seven out of ten pigeons. It has been suggested that serotonergic mechanisms may play a role in the emetic effects of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, since the inhibition of 5-HT synthesis by PCPA reduces the emesis induced by 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in pigeons (Preziosi et al., 1992). Although there may be species differences in 5-HT3 receptors, the cisplatin-induced early emesis in pigeons may be mediated partially via serotonergic mechanisms.

Effect of vagotomy on the cisplatin-induced emesis

The role of 5-HT, and also of the afferent vagus nerve in cisplatin-induced early emesis has been confirmed in animal studies. Cisplatin is known to cause intestinal damage and release of 5-HT in ferrets (Gunning et al., 1987; Stables et al., 1987), and 5-HT stimulates vagal afferent fibres (see reviews by Andrews et al., 1988; Naylor & Rudd, 1996). Vagotomy has been shown to completely inhibit cisplatin-induced emesis in suncus murinus (Mutoh et al., 1992). In dogs and ferrets, it has been observed that cisplatin-induced early emesis is inhibited partially by vagotomy, and completely by the combination of vagotomy and splanchnicectomy (Ito et al., 1987; Hawthorn et al., 1988; Andrews et al., 1990; Fukui et al., 1992). However, the role of the vagus nerve may differ depending on the species. Combined transsection of the vagus and greater splanchnic nerves in cats has little effect on cisplatin-induced emesis other than a small increase in the latency time of the first emetic episode (Miller & Nonaka, 1992).

In the present study, bilateral vagotomy did not affect the incidence of cisplatin-induced emesis in pigeons, but prolonged the latency time to the onset of early emesis and reduced the number of emetic responses in both early and delayed phases. While we did not cut the greater splanchnic nerve in the pigeon, our results suggest that the vagus nerve is partly involved, but is not of major importance in cisplatin-induced emesis in pigeons.

Effect of dexamethasone on cisplatin-induced emesis

Dexamethasone (1 mg kg−1, i.m.), at a dose which has antiemetic effects against cisplatin-induced early and delayed emesis in ferrets (Rudd & Naylor, 1996; 1997), markedly reduced the cisplatin-induced early and delayed emesis in the pigeon. Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone and methylprednisolone are known to have antiemetic effects against cisplatin in humans (Rich et al., 1980; Aapro & Alberts, 1981), and in ferrets (Marr et al., 1991; Rudd et al., 1996). The combination of corticosteroids and 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are highly effective in preventing acute and delayed cisplatin-induced emesis in humans (Smith et al., 1991; Smyth et al., 1991; Chevallier et al., 1994), and in ferrets (Rudd & Naylor, 1996). It has been generally proposed that the inhibition of prostanoid synthesis by corticosteroids may be involved (Rich et al., 1980; Rudd et al., 1996), but a role for prostanoids in the emetic response to cytotoxic drugs has not been identified. Additionally, corticosteroids are thought to stabilize membranes and affect the blood-brain barrier permeability to reduce the influx of emetogenic substances to the central nervous system (Hawthorn & Cunningham, 1990; Naylor & Rudd, 1996). Further studies are required to elucidate the precise mechanisms of the antiemetic effect of dexamethasone.

In conclusion, cisplatin (4 mg kg−1, i.v.) induced early and delayed emesis in the pigeon with peaks at 2–3 and 10–23 h after administration, respectively. The cisplatin-induced emetic response had markedly declined after 48 h. Reserpine completely and dexamethasone markedly reduced the emesis in both early and delayed phases. PCPA, which decreased the levels of 5-HT and 5-HIAA in brain and intestine without affecting the levels of NA and DA, partly reduced the number of early emetic responses, but did not affect the delayed emesis. Bilateral vagotomy did not affect the incidence of cisplatin-induced emesis, but prolonged the latency time to the onset of early emesis and reduced the number of emetic responses in both early and delayed phases. The above results suggest that cisplatin-induced early emesis in the pigeon is partially associated with the vagal nerve and reserpine-sensitive monoaminergic systems including the serotonergic system, and that delayed emesis is associated with monoaminergic systems except the serotonergic system.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms Sonoko Ohata for her excellent technical assistance, and Dr Yoshinori Masuo (Second Department of Physiology, Toho University School of Medicine) for his helpful advice and discussion of the HPLC studies. This study was partially supported by the Project Research Grant of Toho University School of Medicine in 1997 (No. 9–24).

Abbreviations

- DA

dopamine

- DOPAC

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- EDTA·2Na

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt

- 5-HIAA

5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin)

- HVA

homovanillic acid

- NA

noradrenaline

- NM

normetanephrine

- PCPA

p-chlorophenylalanine

References

- AAPRO M.S., ALBERTS D.S. High dose dexamethasone for prevention of cis-platin-induced vomiting. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1981;7:11–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00258206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALFIERI A.B., CUBEDDU L.X. Treatment with para-chlorophenylalanine antagonises the emetic response and the serotonin-releasing actions of cisplatin in cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;71:629–632. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDREWS P.L.R., DAVIS C.J., BINGHAM S., DAVIDSON H.I.M., HAWTHORN J., MASKELL L. The abdominal visceral innervation and the emetic reflex: pathways, pharmacology, and plasticity. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1990;68:325–345. doi: 10.1139/y90-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDREWS P.L.R., RAPEPORT W.G., SANGER G.J. Neuropharmacology of emesis induced by anti-cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1988;9:334–341. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES J.M., BARNES N.M., COSTALL B., NAYLOR R.J., TATTERSALL F.D. Reserpine, para-chlorophenylalanine and fenfluramine antagonise cisplatin-induced emesis in the ferret. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:783–790. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEVALLIER B., MARTY M., PAILLARSE J.-M., THE ONDANSETRON STUDY GROUP Methylprednisolone enhances the efficacy of ondansetron in acute and delayed cisplatin-induced emesis over at least three cycles. Br. J. Cancer. 1994;70:1171–1175. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN M.L., BLOOMQUIST W., GIDDA J.S., LACEFIELD W. Comparison of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist properties of ICS205-930, GR38032F and zacopride. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;248:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTALL B., DOMENEY A.M., NAYLOR R.J., TATTERSALL F.D. 5-Hydroxytryptamine M-receptor antagonism to prevent cisplatin-induced emesis. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25:959–961. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTALL B., DOMENEY A.M., NAYLOR R.J., TATTERSALL F.D. Emesis induced by cisplatin in the ferret as a model for the detection of anti-emetic drugs. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:1321–1326. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUBEDDU L.X., HOFFMANN I.S., FUENMAYOR N.T., FINN A.L. Efficacy of ondansetron (GR 38032F) and the role of serotonin in cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;322:810–816. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003223221204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE MULDER P.H.M., SEYNAEVE C., VERMORKEN J.B., VAN LIESSUM P.A., MOLS-JEVDEVIC S., ALLMAN E.L., BERANEK P., VERWEIJ J. Ondansetron compared with high-dose metoclopramide in prophylaxis of acute and delayed cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Ann. Int. Med. 1990;113:834–840. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLORCZYK A.P., SCHURIG J.E., BRADNER W.T. Cisplatin-induced emesis in the ferret: A new animal model. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1982;66:187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKUI H., YAMAMOTO M., SATO S. Vagal afferent fibers and peripheral 5-HT3 receptors mediate cisplatin-induced emesis in dogs. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1992;59:221–226. doi: 10.1254/jjp.59.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANDARA D.R. Progress in the control of acute and delayed emesis induced by cisplatin. Eur. J. Cancer. 1991;27 Suppl. 1:S9–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANDARA D.R., HARVEY W.H., MONAGHAN G.G., PEREZ E.A., HESKETH P.J. Delayed emesis following high-dose cisplatin – a double-blind randomised comparative trial of ondansetron (GR 38032F) versus placebo. Eur. J. Cancer. 1993;29A Suppl. 1:S35–S38. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRÉLOT L., LE STUNFF H., MILANO S., BLOWER P.R., ROMAIN D. Repeated administration of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist granisetron reduces the incidence of delayed cisplatin-induced emesis in the piglet. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUNNING S.J., HAGAN R.M., TYERS M.B. Cisplatin induces biochemical and histological changes in the small intestine of the ferret. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;90:135P. [Google Scholar]

- GYLYS J.A., DORAN K.M., BUYNISKI J.P. Antagonism of cisplatin induced emesis in the dog. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1979;23:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAWTHORN J., CUNNINGHAM D. Dexamethasone can potentiate the anti-emetic action of a 5HT3 receptor antagonist on cyclophosphamide induced vomiting in the ferret. Br. J. Cancer. 1990;61:56–60. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAWTHORN J., OSTLER K.J., ANDREWS P.L.R. The role of the abdominal visceral innervation and 5-hydroxytryptamine M-receptors in vomiting induced by the cytotoxic drugs cyclophosphamide and cis-platin in the ferret. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. 1988;73:7–21. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1988.sp003124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO J., OKADA M., ABO T., OKAMOTO Y., YAMASHITA T., TAKAHASHI K. Fundamental study on the control of cisplatin-induced emesis in dogs. Jpn. J. Cancer Chemother. 1987;14:706–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARTEN H.J., HODOS W. A stereotaxic atlas of the brain of the pigeon 1967Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press; 78–108.(Columba livia). pp [Google Scholar]

- KOE B.K., WEISSMAN A. p-Chlorophenylalanine: A specific depletor of brain serotonin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1966;154:499–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRIS M.G., GRALLA R.J., CLARK R.A., TYSON L.B., O'CONNELL J.P., WERTHEIM M.S., KELSEN D.P. Incidence, course, and severity of delayed nausea and vomiting following the administration of high-dose cisplatin. J. Clin. Oncol. 1985;3:1379–1384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.10.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASZLO J. Nausea and vomiting as major complication of cancer chemotherapy. Drugs. 1983;25 Suppl. 1:1–7. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198300251-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASZLO J., LUCAS V.S. Emesis as a critical problem in chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981;305:948–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198110153051609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LELIEVELD P., VAN DER VIJGH W.J.F., VAN VELZEN D. Preclinical toxicology of platinum analogues in dogs. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 1987;23:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(87)90148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LONDON S.W., MCCARTHY L.E., BORISON H.L. Suppression of cancer chemotherapy-induced vomiting in the cat by nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid (40465) Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1979;160:437–440. doi: 10.3181/00379727-160-40465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUCOT J.B. Blockade of 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptors prevents cisplatin-induced but not motion- or xylazine-induced emesis in the cat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989;32:207–210. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARR H.E., DAVEY P.T., BLOWER P.R. The effect of dexamethasone, alone or in combination with granisetron, on cisplatin-induced emesis in the ferret. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104 Suppl.:371P. [Google Scholar]

- MARTY M., POUILLART P., SCHOLL S., DROZ J.P., AZAB M., BRION N., PUJADE-LAURAINE E., PAULE B., PAES D., BONS J. Comparison of the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (serotonin) antagonist ondansetron (GR 38032F) with high-dose metoclopramide in the control of cisplatin-induced emesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;322:816–821. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003223221205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUKI N., UENO S., KAJI T., ISHIHARA A., WANG C.-H., SAITO H. Emesis induced by cancer chemotherapeutic agents in the Suncus murinus: A new experimental model. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1988;48:303–306. doi: 10.1254/jjp.48.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCARTHY L.E., BORISON H.L. Cisplatin-induced vomiting eliminated by ablation of the area postrema in cats. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1984;68:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILANO S., BLOWER P., ROMAIN D., GRÉLOT L. The piglet as a suitable animal model for studying the delayed phase of cisplatin-induced emesis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;274:951–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER A.D., NONAKA S. Mechanisms of vomiting induced by serotonin-3 receptor agonists in the cat: Effect of vagotomy, splanchnicectomy or area postrema lesion. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;260:509–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUTOH M., IMANISHI H., TORII Y., TAMURA M., SAITO H., MATSUKI N. Cisplatin-induced emesis in Suncus murinus. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1992;58:321–324. doi: 10.1254/jjp.58.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAYLOR R.J., RUDD J.A. Mechanisms of chemotherapy/radiotherapy-induced emesis in animal models. Oncology. 1996;53 suppl. 1:8–17. doi: 10.1159/000227634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PREZIOSI P., D'AMATO M., DEL CARMINE R., MARTIRE M., POZZOLI G., NAVARRA P. The effects of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists on cisplatin-induced emesis in the pigeon. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;221:343–350. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90721-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICH W.M., ABDULHAYOGLU G., DISAIA P. Methylprednisolone as an antiemetic during cancer chemotherapy – a pilot study. Gynecol. Oncol. 1980;9:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(80)90027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RITTENBERG C., GRALLA R.J., LETTOW L., CRONIN M.D., KARDINAL C.G. New approaches in preventing delayed emesis: Altering the time of regimen initiation and use of combination therapy in 109 patient trial. Proc. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1995;14:526. [Google Scholar]

- RUDD J.A., BUNCE K.T., NAYLOR R.J. The interaction of dexamethasone with ondansetron on drug-induced emesis in the ferret. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:91–97. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUDD J.A., JORDAN C.C., NAYLOR R.J. Profiles of emetic action of cisplatin in the ferret: a potential model of acute and delayed emesis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;262:R1–R2. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUDD J.A., NAYLOR R.J. Effects of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists on models of acute and delayed emesis induced by cisplatin in the ferret. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUDD J.A., NAYLOR R.J. An interaction of ondansetron and dexamethasone antagonizing cisplatin-induced acute and delayed emesis in the ferret. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUDD J.A., NAYLOR R.J. The actions of ondansetron and dexamethasone to antagonise cisplatin-induced emesis in the ferret. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;322:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUFF P., PASKA W., GOEDHALS L., POUILLART P., RIVIÈRE A., VOROBIOF D., BLOCH B., JONES A., MARTIN C., BRUNET R., BUTCHER M., FORSTER J., MCQUADE B. Ondansetron compared with granisetron in the prophylaxis of cisplatin-induced acute emesis: A multicentre double-blind, randomised, prallel-group study. Oncology. 1994;51:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000227321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH W.L., CALLAHAM E.M., ALPHIN R.S. The emetic activity of centrally administered cisplatin in cats and its antagonism by zacopride. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1988;40:142–143. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH D.B., NEWLANDS E.S., RUSTIN G.J.S., BEGENT R.H.J., HOWELLS N., MCQUADE B., BAGSHAWE K.D. Comparison of ondansetron and ondansetron plus dexamethasone as antiemetic prophylaxis during cisplatin-containing chemotherapy. Lancet. 1991;338:487–490. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMYTH J.F., COLEMAN R.E., NICOLSON M., GALLMEIER W.M., LEONARD R.C.F., CORNBLEET M.A., ALLAN S.G., UPADHYAYA B.K., BRUNTSCH U. Does dexamethasone enhance control of acute cisplatin induced emesis by ondansetron. Br. Med. J. 1991;303:1423–1426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6815.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STABLES R., ANDREWS P.L.R., BAILEY H.E., COSTALL B., GUNNING S.J., HAWTHORN J., NAYLOR R.J., TYERS M.B. Antiemetic properties of the 5HT3-receptor antagonist, GR38032F. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1987;14:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(87)90026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORII Y., SAITO H., MATSUKI N. Selective blockade of cytotoxic drug-induced emesis by 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in Suncus murinus. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1991;55:107–113. doi: 10.1254/jjp.55.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]