Abstract

Whole-cell patch clamp experiments were used to investigate the transduction mechanism of adenosine A2A receptors in modulating N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced currents in rat striatal brain slices. The A2A receptor agonist 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS 21680) inhibited the NMDA, but not the (S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) current in a subset of striatal neurons.

Lucifer yellow-filled pipettes in combination with immunostaining of A2A receptors were used to identify CGS 21680-sensitive cells as typical medium spiny striatal neurons.

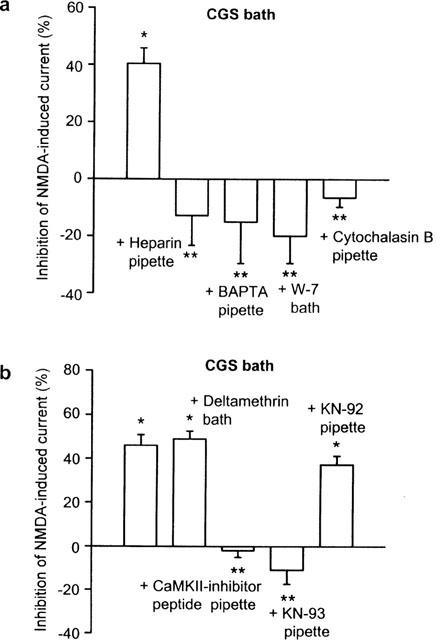

Dibutyryl cyclic AMP and the protein kinase A activator Sp-cyclic AMPs, but not the protein kinase A inhibitors Rp-cyclic AMPS or PKI(14–24)amide abolished the inhibitory effect of CGS 21680. The phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122, but not the inactive structural analogue U-73343 also interfered with CGS 21680. The activation of protein kinase C by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate or the blockade of this enzyme by staurosporine did not alter the effect of CGS 21680. Heparin, an antagonist of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) and a more efficient buffering of intracellular Ca2+ by BAPTA instead of EGTA in the pipette solution, abolished the CGS 21680-induced inhibition.

The calmodulin antagonist W-7 and cytochalasin B which enhances actin depolymerization also prevented the effect of CGS 21680; the calmodulin kinase II inhibitors CaM kinase II(281–309) and KN-93 but not the inactive structural analogue KN-92 were also effective. The calcineurin inhibitor deltamethrin did not interfere with CGS 21680.

It is suggested that the transduction mechanism of A2A receptors to inhibit NMDA receptor channels is the phospholipase C/InsP3/calmodulin and calmodulin kinase II pathway. The adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A and phospholipase C/protein kinase C pathways do not appear to be involved.

Keywords: Striatum, adenosine A2A receptor, NMDA receptor, AMPA receptor, patch clamp

Introduction

The neostriatum is a complex area of the forebrain, involved in the regulation of motor activity and stereotyped behaviour (Angulo & McEwen, 1994). It receives information from the cortex which is processed onto a limited number of output targets (Smith & Bolam, 1990; Parent & Hazrati, 1993). The principal neuronal cell population of the striatum consists of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic medium spiny projection neurons which receive glutamatergic input from the cerebral cortex and thalamus and, in addition, dopaminergic input from the substantia nigra pars compacta (Angulo & McEwen, 1994; Di Chiara et al., 1994). Medium spiny neurons contribute to two distinct efferent pathways ending in the internal segment of the globus pallidus/substantia nigra pars reticulata and in the external segment of the globus pallidus, respectively. Striatonigral neurons contain GABA and substance P, while striatopallidal neurons contain GABA and enkephalin (Smith & Bolam, 1990). Medium spiny neurons, by way of intrastriatal collaterals also provide a major proportion of intrinsic synaptic input (Di Chiara et al., 1994).

Four adenosine receptors (P1 purinoceptors) have been cloned to date, and referred to as the A1, A2A, A2B and A3 subtypes (Fredholm et al., 1994; Olah & Stiles, 1995). Whereas A1 and A3 receptors are negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase via a G protein, both A2A and A2B receptors are positively coupled to the same effectors (Fredholm et al., 1994; Latini et al., 1996). Only A1 and A2A receptors occur in neurons, have a low threshold for activation by endogenous adenosine and, in consequence, are capable of exerting physiological functions in the CNS (Jacobson, 1996). In contrast to A1 receptors, A2A receptors exhibit a rather circumscribed distribution in the brain; they are believed to be concentrated in the striatum and to a lesser extent also in the hippocampus and cortex (Sebastiao & Ribeiro, 1996; Ongini & Fredholm, 1996). The cellular localization of the A2A receptor mRNA closely matches that of the dopamine D2 receptor mRNA, being expressed in striatopallidal medium spiny neurons that also express enkephalin (Schiffmann et al., 1991; Ongini & Fredholm, 1996). This co-localization of the two receptors is the morphological basis for a mutually antagonistic interaction (Ferré et al., 1993),

It has recently been shown that adenosine A2A receptor activation inhibits the conductance of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channels in a subset of rat neostriatal neurons (Nörenberg et al., 1997). It was suggested that the site of interaction is at the striatopallidal medium spiny neurons and that a phosphorylation of the channel protein is the most likely transduction mechanism of A2A receptors. The aim of the present study was to confirm or dismiss these suggestions and to clarify whether (S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors are also modulated by A2A receptor activation. A preliminary account of some of the results has appeared as a congress report (Nörenberg et al., 1998).

Methods

Brain slice preparation

Young Wistar rats (14–27 days old) were decapitated and their brains were quickly removed and submerged in ice cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 of the following composition (mM): NaCl 126, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 2.4, MgCl2 1.3, NaHCO3 26 and glucose 10; pH 7.4. Thin coronal slices from hemisected forebrains, 150–200 μm in thickness, containing parts of the neocortex-corpus callosum and the neostriatum were prepared by a tissue slicer (Vibratome 1000; Plano, Marburg, Germany). After being sectioned, 3–5 slices obtained from a single brain were transferred to a holding chamber and stored in oxygenated aCSF at 36°C for at least 1 h before use. Then, single slices were continuously superfused (3 ml min−1) with oxygenated aCSF at room temperature (22–25°C) in a recording bath (300–400 μl volume). The bath solution differed from aCSF used for incubation, in that Mg2+ was omitted in order to augment NMDA-induced responses. The slices were left to recover for at least 15 min before the start of individual experiments, either in Mg2+-free aCSF when NMDA was used as an excitatory amino acid (EAA) receptor agonist, or in Mg2+-containing aCSF when AMPA was used for the same purpose.

Tight seal whole-cell recording

To record membrane currents of medium spiny neurons in striatal brain slices, procedures similar to those described previously were used but without cleaning the tissue with a pipette (Edwards et al., 1989). Experiments were performed and cells were visualized directly with an upright interference contrast microscope and a ×40 water immersion objective (Axioscop FS; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The microscope was connected to a video camera sensitive to infrared light (Newvicon C 2400-07-C; Hamamatsu, Herrsching, Germany). Patch pipettes were produced by a micropipette puller (Flaming/Brown P-97; Sutter, Novato, California, U.S.A.) from borosilicate glass capillaries (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany) having an outer diameter of 2 mm. They were filled with intracellular solution of the following composition (mM): K-gluconate 140, NaCl 10, MgCl2 1, HEPES (N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulphonic acid)) 10, EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis-(β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid) 11, MgATP 1.5 and GTP 0.3; pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH. In some experiments, 5.5 mM BAPTA (1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid) and 5.5 mM K-gluconate was used to substitute 11 mM EGTA. In other experiments, K-gluconate was replaced by 125 mM Cs-methanesulphonate, 3 mM KCl and 4 mM NaCl, while leaving the residual composition of the pipette solution unaltered; the pH was set to 7.3 by adding CsOH (Crepeda et al., 1998). Pipette resistances were in the range of 3–7 MΩ. The liquid junction potential (VLJ) between the bath- and pipette solutions at 22°C was calculated according to Barry (1994); it was found to be 15.2 mV for the standard pipette solution, 15.9 mV for the BAPTA containing solution and 10.6 mV for the Cs-methanesulphonate containing solution. Therefore, all membrane potential values given in this study were corrected for VLJ and cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −80 mV or +30 mV taking into account this potential.

The membrane potential of 30 selected neurons was measured in the current clamp mode of the patch amplifier (List EPC-7, Darmstadt, Germany) immediately after establishing whole cell access by using standard pipette solution (−78.4±2.6 mV). Then, the system was left for 5–10 min to allow for the settling of a diffusion equilibrium between the patch pipette and the cell interior, before current responses to NMDA or AMPA were recorded in the voltage clamp mode. Whole cell recordings of 30–50 min duration could be routinely achieved with stable membrane properties of the cells throughout. At the end of the experiment, the membrane potential was re-determined (−79.7±2.5 mV; P>0.05) in order to exclude its possible time-dependent change. Compensation of capacitance (Cm; 38.6±2.1 pF) and series resistance (Rs; 28.0±1.5 MΩ; n=30 each) was achieved with the inbuilt circuitry of the amplifier. NMDA- and AMPA-induced inward currents were similar in amplitude both with and without 50–80% compensation of Rs. Therefore, and to avoid the risk of accidental overcompensation, this procedure was not generally used (Llano et al., 1991). However, the occurrence of action currents during the application of NMDA or AMPA was taken as an indication for improper space clamp and these recordings were discarded from data evaluation. In the residual neurons, the membrane potential was not measured but otherwise the experimental procedure was similar to that described previously.

Data were filtered at 3–10 kHz with the inbuilt filter of the EPC-7, digitized at 0.15 kHz (Model 1401; Cambridge Electronic Devices, Cambridge, U.K.). Data analysis was performed by use of commercially available patch and voltage clamp software (Cambridge Electronic Devices, Cambridge, U.K.).

Selection of cells

The principal cell type of the striatum is the GABAergic medium spiny projection neuron (90–95% of the total population; Bishop et al., 1982). These cells are characterized by a small soma (about 13 μm diameter), a resting membrane potential negative to −60 mV and under in vitro conditions, a lack of spontaneous activity (Calabresi et al., 1987). All cells chosen for recording were neurons, as judged from the firing of action potentials during the establishment of the gigaseal.

Application of drugs

Different drugs were applied by changing the superfusion medium by means of three-way taps. At the constant flow rate of 3 ml min−1 about 20 s were required until the drugs reached the bath. In order to construct concentration-response curves, NMDA (1–1000 μM) or AMPA (0.3–310 μM) was used as an agonist. The same concentration of the respective compound was applied twice for 1.5 min each (T1 and T2) being separated by a superfusion period of 10 min with drug-free aCSF. In all further experiments, concentrations of NMDA (10 μM) and AMPA (3 μM) were chosen which evoked reproducible inward (or at +30 mV outward) current when applied according to the above time schedule. In experiments with NMDA, a submaximal concentration of the adenosine A2A agonist 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino - 5′ -N- ethylcarboxamidoadenosine hydrochloride (CGS 21680; 0.1 μM; Nörenberg et al., 1997) was present in the bath 5 min before and during the second application of NMDA (10 μM; T2). Drugs known to modulate intracellular signalling pathways were added to the superfusion medium 15 min before the start of and throughout the experiments; alternatively these drugs were dissolved in the pipette solution and were, thereby, also present throughout. When the effects of modulators of intracellular signalling pathways were investigated alone, they were applied to the bath medium 5 min before T1 and were present thereafter both during T2 and (10 min later) during T3. In experiments with AMPA, selective agonists of A1 and A2 receptors or adenosine itself were present in the superfusion medium 5 min before and during the second application of AMPA (3 μM; T2).

Intracellular labelling and immunofluorescence

Micropipettes were filled with standard intracellular solution also containing lucifer yellow (1.5%). The effect of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) was tested on the NMDA (10 μM)-induced current as described previously. After recording, slices were fixed in paraformaldehyde (4% in 0.1 M phosphate buffer; pH 7.2) for 1 h. After washing in Tris buffered saline (TBS; 0.05 M; pH 7.6), and blocking with 3% normal goat serum (NGS) in TBS, the slices were incubated in an antibody mixture from mouse anti-A2A (1:5000) and rabbit anti-lucifer yellow IgG (1:1500) with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1% NGS in TBS for 48 h at 4°C. Then, the slices were washed in 1% NGS in TBS and incubated in a mixture of the fluorescence labelled secondary antibodies CY3-conjugated goat anti mouse IgG (1:800) and FITC-conjugated goat anti rabbit IgG (1:100) in 1% NGS in TBS. After 2 h, the slices were washed in TBS, mounted, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in n-butylacetate and coverslipped in entellan. The double immunofluorescence was investigated by a scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an argon laser emitting at 488 nm and a helium/neon laser emitting at 543 nm.

Statistics

Since the amplitudes of NMDA- and AMPA-induced currents showed great variabilities, the effects of all drugs applied before and during T2 were expressed as percentage inhibition of the respective currents measured at T1. Mean values±s.e.mean of n experiments are given throughout. Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on ranks followed by the Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison of the means and for comparison of the means with zero. For multiple comparisons between independent values, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA followed by a t-test with Bonferroni's correction was employed instead. In the case of repeated measurements on the same preparation, Friedman repeated measures ANOVA on ranks followed by a Wilcoxon-signed rank test was used. A probability level of 0.05 or less was considered to be statistically significant.

Materials

The following drugs and chemicals were used: calmodulin kinase II inhibitor (281–309), cytochalasin B, deltamethrin, lucifer yellow CH dilithium salt, N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide hydrochloride (W-7) (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, Bad Soden, Germany); mouse anti-A2A receptor IgG (Heidi Figler, Dr Joel Linden, Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.A.); CY3-conjugated goat anti mouse IgG, FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immuno Research, Baltimore, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.); entellan (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany); rabbit anti-lucifer yellow IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, U.S.A.); PKI(14-24)amide (Peninsula, Belmont, California, U.S.A.); (S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid ((S)-AMPA), 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA), heparin sodium (porcine), 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine hydrochloride (CGS 21680), (2S)-N6-(2-endo-norbornyl)adenosine (S(−)-ENBA), S(4-nitrobenzyl)-6-thioguanosine (NBTG), 2-(N-(4′-methoxybenzenesulphonyl))amino-N - (4′ - chlorophenyl) - 2 -propenyl-N-methylbenzylamine phosphate (KN-92), N-(2-(((3-(4′-chlorophenyl)-2-propenyl)methylamino)methyl)phenyl)-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4′-methoxy-benzenesulphonamide phosphate (KN-93), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), Sp- and Rp-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphothioate triethylamine (Sp-cyclic AMPS, Rp-cyclic AMPS), staurosporine, 1-(6-(((17β)-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)amino)hexyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (U-73122), 1(6-((17β)-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)amino)hexyl)-2,5-pyrrolidinedione (U-73343) (RBI; Natick, Massachusetts, U.S.A.); adenosine, adenosine 5′-triphosphate magnesium salt (MgATP), guanosine 5′-triphosphate lithium salt (GTP), N6,2′-O-dibutyryladenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (dibutyryl cyclic AMP), nifedipine, N-methyl-D-aspartate sodium salt (NMDA), tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA), tetrodotoxin (TTX) (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany); normal goat serum (NGS) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, U.S.A.).

Stock solutions (10–100 mM) of drugs were prepared with distilled water or dimethyl sulphoxide (cytochalasin B, nifedipine, PMA, staurosporine, U-73122, U-73343) and aliquots were stored at −20°C. Further dilutions were made daily with the extra- or intracellular solution as appropriate. Equivalent quantities of the solvent had no effect.

Results

Effects of NMDA and AMPA on striatal neurons

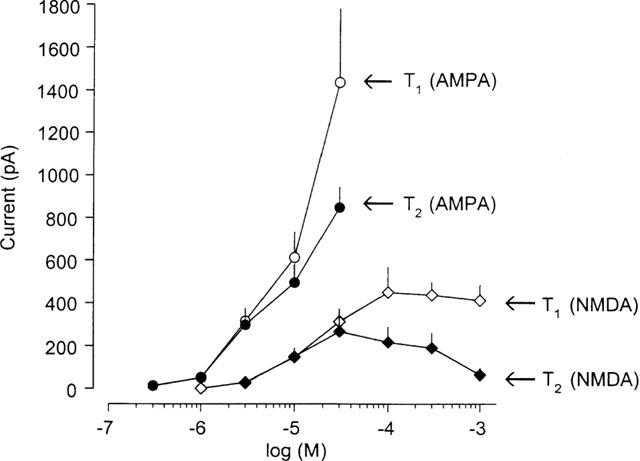

The effects of NMDA on medium spiny neurons were investigated in Mg2+-free aCSF and at a holding potential of −80 mV. Figure 1 shows that the repeated application of NMDA (1–1000 μM), for 1.5 min and with an interval of 10 min, caused inward current responses, which were reproducible in the lower range of concentrations (⩽10 μM; Figure 1). However, the current amplitude decreased from T1 to T2, thereafter (>10 μM; Nörenberg et al., 1997). The maximum effect at T1 was reached with 100 μM NMDA and did not rise further with 300 and 1000 μM NMDA. AMPA effects were studied at the same holding potential, but in the continuous presence of Mg2+ (Figure 1). In this case, there was no maximum inward current at T1 up to 30 μM AMPA. Once again reproducible currents were evoked at relatively low concentrations only (⩽3 μM; Figure 1). It is interesting to note that AMPA produced much larger currents than NMDA and was active at a lower threshold concentration. These results allowed to choose 10 μM NMDA and 3 μM AMPA for the further studies.

Figure 1.

Concentration-response relationship for NMDA- and AMPA-induced inward currents in rat striatal neurons elicited at a holding potential of −80 mV. In every neuron the same concentration of NMDA or AMPA were superfused twice for 1.5 min (T1; T2), with 10 min intervals. Experiments with NMDA were carried out in Mg2+-free aCSF. Data points represent 5–18 cells; vertical lines indicate s.e.mean. The concentration-response relationship of NMDA is taken from a previous publication (Nörenberg et al., 1997).

Modulation by adenosine A2A receptors of NMDA receptor channels in a population of striatal neurones

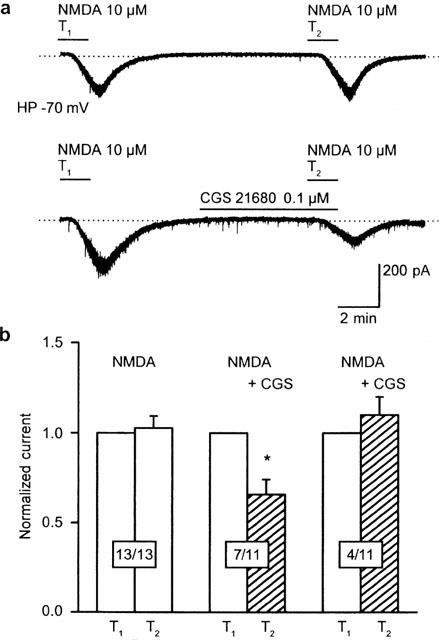

When, in separate experiments, again at a holding potential of −80 mV, NMDA (10 μM) was applied twice, it evoked somewhat larger but reproducible current amplitudes both at T1 (−344.3±67.1 pA) and T2 (−330.1±61.5 pA; P>0.05 and n=17 each) than those shown in Figure 1. The amplitudes of the NMDA (100 μM)-induced currents were normalized at T1 because of the large variability of responses (Figure 2a,b). A submaximal concentration (0.1 μM; see Figure 4c in Nörenberg et al., 1997) of the adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 decreased the effect of NMDA (10 μM) in 7 out of 11 neurons (Figure 2a,b). However, CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) did not act on the residual four cells (Figure 2b). A similar insensitivity to CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) was previously observed in about 20% of striatal neurons and was concluded to be due to the absence of adenosine A2A receptors (Nörenberg et al., 1997; see later). Hence, cells which did not respond to CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) with at least 15% inhibition were discarded from further calculations. Of course this procedure was not used, when the effect of CGS 21680 was antagonized by various manipulations of the intra- and extracellular medium.

Figure 2.

CGS 21680 inhibits the NMDA-induced inward current in a subpopulation of rat striatal neurons. The holding potential was in this and all subsequent experiments, except those shown in Figure 3, −80 mV. (a, upper panel) NMDA (10 μM) was applied twice (T1, T2) for 1.5 min with a 10 min interval between applications. Current responses were reproducible under these conditions. Representative recording. (a, lower panel) HCGS 21680 (0.1 μM) was added to the medium 5 min before and during the second application of NMDA (10 μM; T2). This procedure caused an inhibition of the NMDA-induced current at T2 in a subpopulation of neurons. Representative recording. The dotted line indicates the zero current level both in the upper and lower panels of (a). (b) Reproducibility of NMDA currents in the absence of drugs (13 cells; first set of columns). Inhibition of NMDA currents by CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in a subpopulation of neurons (seven cells out of a total of 11 cells; second set of columns). No inhibition of NMDA currents by CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in the residual subpopulation of neurons (four cells out of a total of 11 cells; third set of columns). Means±s.e.mean of n cells are shown. Currents were normalized with respect to T1. *P<0.05; statistically significant difference from T1.

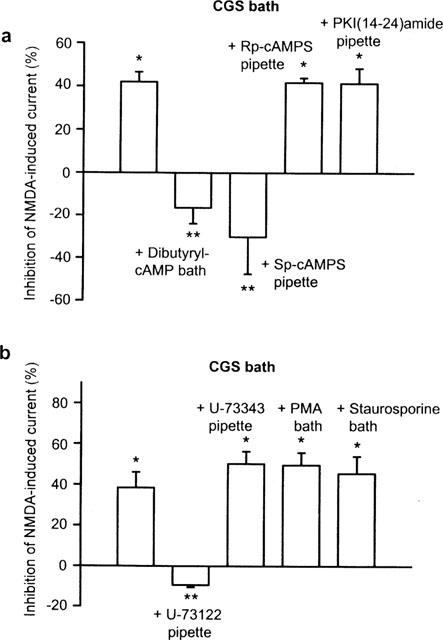

Figure 4.

Inhibition of the CGS 21680-induced depression of NMDA currents by compounds known to alter signal transduction pathways. NMDA (10 μM) and CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) were applied with the protocol shown in Figure 2. (a) Effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) alone (n=15) as well as effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in the presence of dibutyryl cyclic AMP (100 μM; n=7), Sp-cyclic AMPS (30 μM; n=6), Rp-cyclic AMPS (30 μM; n=6) or PKI(14–24)amide (10 μM; n=7). Dibutyryl cyclic AMP was applied to the bath medium, 5 min before T2; Sp- and Rp-cyclic AMPS as well as PKI(14–24)amide were included in the pipette solution. (b) Effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) alone (n=7) as well as effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in the presence of U-73122 (10 μM; n=8), U-73343 (10 μM; n=8), PMA (0.1 μM; n=8) or staurosporine (0.1 μM; n=7). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and staurosporine were added to the bath medium, 5 min before T2; U-73122 and U-73343 were included in the pipette solution. Means±s.e.mean of n cells are shown both in (a) and (b). The decrease of the current amplitudes from T1 to T2 are expressed as percentage inhibition. *P<0.05; significant difference from zero; **P<0.05; significant difference from the first column.

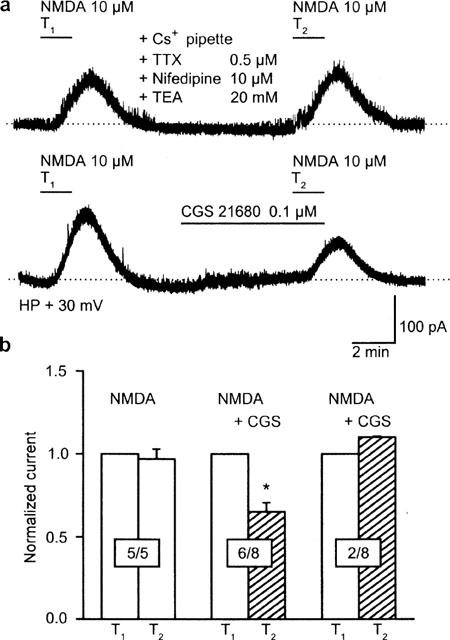

In order to find out, whether a modulation of voltage-dependent ionic conductances is involved in the effect of CGS 21680, the membrane of striatal neurons was clamped at +30 mV; at this holding potential the contribution of selected voltage-dependent inward currents was expected to decrease. In addition, K+ currents were blocked by a combination of Cs+ (125 mM) in the pipette and tetraethylammonium (20 mM) in the bath. Tetrodotoxin (0.5 μM) and nifedipine (10 μM) were also added to block Na+ currents and L-type Ca2+ currents, respectively. When under these conditions NMDA (10 μM) was applied twice for 1.5 min each and with an interval of 10 min, reproducible outward currents were evoked (T1, 286.4±53.2 pA; T2, 273.8±56.1 pA; n=5; P>0.05) (Figure 3a,b). CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) applied 5 min before and during T2 caused an inhibition in six out of eight neurons (Figure 3a,b, while the residual two neurons were unaffected (Figure 3b). The inhibitory effect of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) was similar both at −80 and +30 mV (compare Figures 2b and 3b).

Figure 3.

CGS 21680 inhibits the NMDA-induced inward current in a subpopulation of rat striatal neurons. The holding potential was +30 mV. A combination of intracellular Cs+ (125 mM), as well as extracellular tetrodotoxin (TTX; 0.5 μM), nifedipine (10 μM) and tetraethylammonium (TEA; 20 mM) was used to block K+, Na+ and L-type Ca2+ currents (a, upper panel) NMDA (10 μM) was applied twice (T1, T2) for 1.5 min with a 10 min interval between applications. Current responses were reproducible under these conditions. Representative recording. (a, lower panel) CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) was added to the medium 5 min before and during the second application of NMDA (10 μM; T2). This procedure caused an inhibition of the NMDA-induced current at T2 in a subpopulation of neurons. Representative recording. The dotted line indicates the zero current level both in the upper and lower panels of (a). HP, holding potential. (b) Reproducibility of NMDA currents in the absence of drugs (five cells; first set of columns). Inhibition of NMDA currents by CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in a subpopulation of neurons (six cells out of a total of eight cells; second set of columns). No inhibition of NMDA currents by CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in the residual subpopulation of neurons (two cells out of a total of eight cells; third set of columns). Means±s.e.mean of n cells are shown. Currents were normalized with respect to T1. *P<0.05; statistically significant difference from T1.

Involvement of the adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A pathway in the transduction mechanism of adenosine A2A receptors

All following experiments were made at a holding potential of −80 mV and according to the time schedule shown in Figure 2a. A possible role of the adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A pathway in the transduction mechanism of adenosine A2A receptors was investigated by superfusing the membrane permeable analogue of cyclic AMP, dibutyryl cyclic AMP (100 μM) together with CGS 21680 (0.1 μM). In the absence of dibutyryl cyclic AMP, CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) depressed the NMDA current, while in the presence of this analogue CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) had no effect (Figure 4a). In some experiments, NMDA (10 μM) was superfused three times. Application of dibutyryl cyclic AMP (100 μM) alone potentiated the effect of NMDA (10 μM) from T1 to T2 (by 49.2±10.7%) and from T1 to T3 (by 44.3±11.9%; n=7 and P<0.05 each), respectively.

Then, Sp-cyclic AMPS (30 μM) an activator of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A or Rp-cyclic AMPS (30 μM) an inhibitor of this enzyme was included in the pipette solution (Figure 4a). Whereas Sp-cyclic AMPS prevented, Rp-cyclic AMPS did not alter the inhibitory effect of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM). The intracellularly applied protein kinase A inhibitor 14-24 amide (PKI(14-24)amide; 10 μM) also failed to interfere with CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) (Figure 4a). Since the amplitude of the NMDA (10 μM)-induced current considerably varied between individual experimental groups (see above), we did not statistically compare the currents at T1 recorded in the presence or absence of drugs in the pipette solution.

Involvement of the phospholipase C/protein kinase C or phospholipase C/inositol trisphosphate/calmodulin and calmodulin kinase II pathway in the transduction mechanism of adenosine A2A receptors

Dialysis of striatal neurons via the micropipette with the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 (10 μM), abolished the inhibitory effect of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) on the current response to NMDA (10 μM); the inactive structural analogue U-73343 (10 μM) did not interfere with CGS 21680 (0.1 μM; Figure 4b). The activation of protein kinase C by bath applied phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 0.1 μM) or the blockade of this enzyme by staurosporine (0.1 μM) also failed to prevent the effect of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) (Figure 4b). PMA (0.1 μM), when given alone, did not alter the NMDA (10 μM)-induced current at T2 (25.3±16.1%) or T3 (31.4±18.0%; n=8 and P>0.05 each) in comparison with the current recorded at T1. Staurosporine (0.1 μM) by itself was also ineffective (T2, −4.1±6.1%: T3, 2.4±9.5%; n=7 and P>0.05 each).

The inclusion of heparin (10 mg ml−1) into the pipette solution to antagonize inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) abolished the effect of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) on the NMDA (10 μM)-induced current (Figure 5a). A more efficient buffering of intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA (5.5 mM) instead of the usual EGTA (11 mM) also prevented the inhibitory activity of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM); the bath application of the calmodulin antagonist W-7 (30 μM) had the same effect (Figure 5a). Cytochalasin B (10 μM) which enhances actin depolymerization also interfered with the action of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM; Figure 5a). Finally, W-7 (30 μM) when given alone, did not alter the current response to NMDA (10 μM) from T1 to T2 (0.3±6.6%) or T3 (6.2±9.7%; n=7; P>0.05).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of the CGS 21680-induced depression of NMDA currents by compounds known to alter signal transduction pathways. NMDA (10 μM) and CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) were applied with the protocol shown in Figure 2. (a) Effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) alone (n=8) as well as effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in the presence of heparin (10 mg ml−1; n=10), BAPTA (5.5 mM; n=7), W-7 (30 μM; n=6) or cytochalasin B (10 μM; n=9). W-7 was added to the bath medium, 5 min before T2; heparin, BAPTA and cytochalasin B were included in the intracellular solution. (b) Effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) alone (n=6) as well as effects of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) in the presence of deltamethrin (0.5 μM; n=7), the calmodulin kinase II(281–309) inhibitor (CaMK-II inhibitor peptide; 10 μM; n=6), KN-93 (3 μM; n=5) and KN-92 (3 μM; n=4). Deltamethrin was added to the bath medium, 5 min before T2; the CaMKII inhibitor peptide, KN-93 and KN-92 were added to the intracellular solution. Means±s.e.mean of n cells are shown both in (a) and (b). The decrease of the current amplitudes from T1 to T2 are expressed as percentage inhibition. *P<0.05; significant difference from zero; **P<0.05; significant difference from the first column.

Superfusion with the calcineurin inhibitor deltamethrin (0.5 μM) failed to alter the effect of CGS 21680 (0.1 μM), while dialysis of the cell interior with the calmodulin kinase II inhibitor CaM kinase II(281–309) (10 μM) or KN-93 (3 μM) abolished it (Figure 5b). The inactive structural analogue of KN-93, KN-92 (3 μM) did not interfere with CGS 21680 (0.1 μM; Figure 5b). Bath-applied deltamethrin (0.5 μM) or KN-93 (3 μM) were superfused also in the absence of CGS 21680. Under these conditions, the current response to NMDA (10 μM) was not changed by deltamethrin (0.5 μM) at T2 (2.1±7.7%) or at T3 (3.4±6.4%; n=5 and P>0.05 each), when compared with the current recorded at T1. Similarly, KN-93 (3 μM) did not alter the NMDA (10 μM)-induced current from T1 to T2 (−4.5±7.8%) or to T3 (1.8±3.4%: n=7 and P>0.05 each).

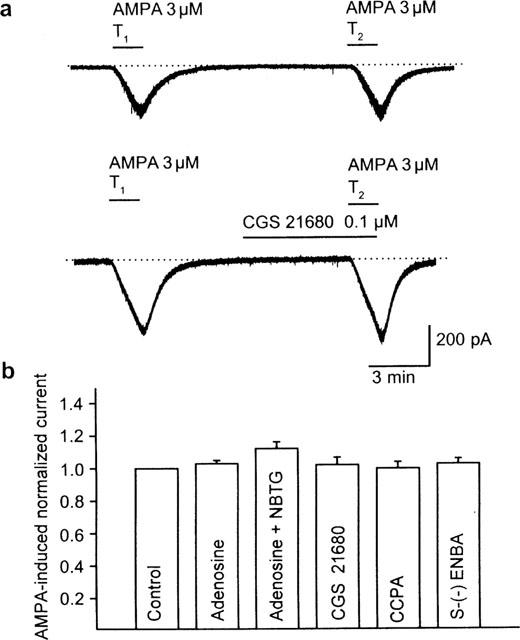

Modulation by adenosine A1 or A2A receptors of AMPA receptor channels in striatal neurones

The repeated application of AMPA (3 μM) caused an inward current which did not decrease from T1 (314.3±58.5 pA) to T2 (297.6±47.6 pA; n=18; P>0.05) (Figure 6). Adenosine (100 μM) itself, either in the presence or absence of the adenosine transport inhibitor S(4-nitrobenzyl)-6-thioguanosine (NBTG; 30 μM) had no effect on AMPA (3 μM)-induced currents. The adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) as well as the A1 receptor agonists 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA; 10 μM) and (2S)-N6-(2-endo-norbornyl)adenosine (ENBA; 10 μM) were also inactive.

Figure 6.

No effect of adenosine receptor agonists on AMPA currents in striatal neurons. (a, upper panel) AMPA (3 μM) was applied twice (T1, T2) for 1.5 min with a 10 min interval between applications. Current responses were reproducible under these conditions. Representative recording. (a, lower panel) CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) was added to the medium 5 min before and during the second application of AMPA (3 μM; T2). This procedure did not alter the AMPA-induced current at T2. Representative recording. (b) Reproducibility of AMPA (3 μM) currents in the absence of drugs (control; n=7). No effect of adenosine (100 μM; n=9)), NBTG (30 μM) plus adenosine (100 μM; n=11), CGS 21680 (0.1 μM; n=7), CCPA (10 μM; n=8) and S(−)-EN (10 μM; n=7), when added 5 min before T2 to the superfusion medium. Means±s.e.mean of n cells are shown. Currents were normalized with respect to T1.

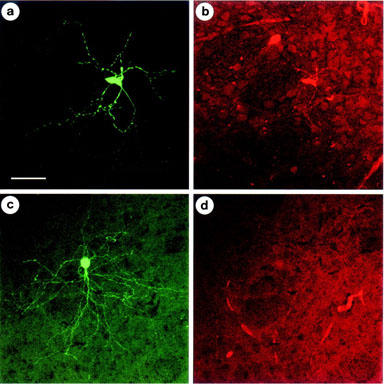

Fluorescence histochemical evidence for the existence of adenosine A2A receptors on striatal neurons

When lucifer yellow-filled micropipettes were used to record membrane currents, subsequently the neurons could be visualized with confocal fluorescence microscopy (Figure 7). All neurons showed the typical morphology of striatal principal cells with dendrites densely covered with spines (yellow-green fluorescence; Figure 7a,c). The primary dendrites gave rise to a dendritic tree of circular or ellipsoidal shape. Whereas the cell shown in Figure 7a responded to CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) with a decrease of the NMDA (10 μM)-induced current by 24% (one out of five similar experiments), the cell shown in Figure 7c did not react to the adenosine A2A receptor agonist (0.05% inhibition; one out of two similar experiments). In correlation with this functional finding, the red A2A receptor-immunoreactivity was observed only in the CGS 21680-sensitive cell population (Figure 7b). In this, but not in the cell documented in Figure 7d, A2A receptors were localized both on the pericaria and the neuronal processes.

Figure 7.

Confocal images of double immunofluorescence using FITC to visualize the intracellular marker lucifer yellow (yellow-green fluorescence) and CY3 to visualize adenosine A2A receptors (red fluorescence) in rat striatal neurons. (a,b) CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) inhibited in this cell the NMDA (10 μM)-induced inward current by 24% at T2. Note the presence of A2A receptors in the pericaria and cell processes of the lucifer yellow labelled neuron. (c,d) CGS 21680 (0.1 μM) had no effect in this cell on the NMDA (10 μM)-induced inward current at T2. For the experimental protocol see Figure 2. All scale bars are 30 μm.

Discussion

In the present study both NMDA and AMPA caused inward currents in striatal neurons, but only the effect of NMDA was inhibited by the adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS 21680 (Jarvis et al., 1989). The effect of CGS 21680 appears to be due to a direct modulation of the NMDA receptor channel, since this agonist was equally active both at −70 and +30 mV holding potentials, although at +30 mV voltage-dependent conductances are less likely to influence responses to exogenous NMDA. At the more positive holding potential a combination of channel-blocking substances (intracellular Cs+, extracellular tetrodotoxin, tetraethylammonium and nifedipine) were also added to diminish the contribution of K+, Na+ and L-type Ca2+ channels (Crepeda et al., 1998). Irrespective of these experimental conditions, CGS 21680 failed to act in about 25% of the neuronal population investigated. Confocal fluorescence histochemistry proved that the CGS 21680-sensitive cells possess A2A receptors, while the CGS 21680-insensitive cells are probably devoid of them. Hence, it is most unlikely that CGS 21680 acts at some other site than the A2A receptor. The confocal fluorescence data in conjunction with the sensitivity of the CGS 21680 effect to pharmacologically relevant concentrations of the A2A receptor antagonistic 8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine (Jacobson et al., 1993), but not of the A1 receptor antagonistic 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX; Lohse et al., 1988) unequivocally proved the existence of modulatory adenosine A2A receptors at a subset of striatal medium spiny neurons (Nörenberg et al., 1997). Under the same conditions, adenosine A1 receptor agonists did not modulate NMDA currents (Nörenberg et al., 1997). Since A2A receptors were reported to be present only at striatopallidal output neurons (Schiffmann et al, 1991), we suggest that CGS 21680 acts at this cell population.

In contrast to NMDA currents, AMPA currents were insensitive both to CGS 21680 and to two structurally unrelated agonists (CCPA, ENBA; Trivedi et al., 1989) for adenosine A1 receptors. Moreover, the endogenous purine, adenosine by itself had no effect, even when the nucleoside uptake was blocked by the transport inhibitor NBTG (Paterson et al., 1977). Such uptake sites are present in the striatum and may heavily decrease agonist efficacy (Geiger & Nagy, 1990).

In the absence of extracellular Mg2+, electrical stimulation within the striatum evoked an excitatory postsynaptic current (e.p.s.c.) which was partially blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 and was abolished by the combination of AP-5 with the AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX (Gerevich et al., 2000). Although previous reports indicated that synaptic currents caused by intrastriatal stimulation are due to the release of both glutamate and GABA (Cherubini et al., 1988; Jiang & North, 1991), GABAA receptors did not mediate the e.p.s.c. in the above study. Since the main intracellular anion was gluconate, the low concentration of Cl− in the pipette solution as well as the limited permeability of the GABAA receptor channel to gluconate (Fatima-Shad & Barry, 1993) may be the reasons for this finding. It is likely, that the e.p.s.c. results from the action of glutamate released from cortical afferents onto striatal neurons (Park et al., 1980). CGS 21680 depressed the e.p.s.c. in eight out of eleven cells; the extent of this effect was comparable to that produced by AP-5 (Gerevich et al., 2000). In addition, the application of CGS 21680 and AP-5 alone or in combination caused the same inhibition. Hence, CGS 21680 appeared to depress in a subpopulation of striatal neurons the NMDA receptor-mediated fraction of the e.p.s.c. It is interesting to note that the ratio of CGS 21680-sensitive and -insensitive neurons was similar irrespective of whether the NMDA receptors were activated by endogenously released or exogenously applied agonists.

Inactivation of G proteins by GDP-β-S (Sternweis & Pang, 1990), abolished the inhibitory effect of CGS 21680 on NMDA currents, indicating G protein coupling of the A2A receptor (Nörenberg et al., 1997). A2A receptors are defined by their ability to stimulate adenylate cyclase and are, therefore, thought to be coupled to the Gs type of G proteins which is linked to the adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A pathway (Fredholm et al., 1994). This may be the mechanism of most excitatory actions in the CNS including the facilitation of GABA release (Mayfield et al., 1993; Sebastiao & Ribeiro, 1996), an effect due to the alleviation of GABA-mediated inhibition of medium spiny projection neurons (Mori et al., 1996). In fact, CGS 21680 induced a small elevation of the cyclic AMP content in rat striatal slices (Lupica et al., 1990). However, the modulation of NMDA receptor channels by adenosine A2A receptor activation may utilize a different transduction pathway.

Ligand-activated cationic channels such as ionotropic EAA receptors and GABAA receptors have been shown either to be regulated by protein phosphorylation or to contain consensus sequences for phosphorylation by protein kinases (Swope et al., 1992; Moss & Smart, 1996). Data with respect to phosphorylation of NMDA receptors by protein kinase A or protein kinase C activation are controversial, varying between no effect (Greengard et al., 1991; Linden & Connor, 1991) and an enhanced response to NMDA (Ben-Ari et al., 1992; Raman et al., 1996). This may be explained at least for protein kinase C effects, by the presence or absence of the C1 cassette phosphorylation site at the carboxy terminal region of the NR1 subunit (Tingley et al., 1997).

We found that the membrane permeable analogue of cyclic AMP, dibutyryl cyclic AMP, known to activate protein kinase A facilitated the NMDA current. An activator of protein kinase C, PMA (Castagna et al., 1982), and a non-selective inhibitor of the enzyme, staurosporine (Wilkinson & Hallam, 1994), were both ineffective. Hence the present evidence suggests that, if anything, protein kinase A, but not protein kinase C, may positively modulate NMDA-induced currents in striatal medium spiny neurons.

None of these protein kinases were involved in the inhibitory effect of CGS 21680. As already mentioned. CGS 21680, a supposed activator of adenylate cyclase and, in consequence, protein kinase A should potentiate the NMDA-induced current rather than depress it. Moreover, dibutyryl cyclic AMP and CGS 21680 should both facilitate the response to NMDA and, when applied together, their effects should be additive rather than antagonistic. The failure to fulfil these expectations argues against the involvement of the adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A pathway in the action of CGS 21680. Further support for this suggestion derives from the findings that Sp-cyclic AMPS, an activator of protein kinase A (Van Haastert et al., 1984) abolished the inhibition of the NMDA current by CGS 21680, while two blockers of the enzyme (Rp-cyclic AMPS, Van Haastert et al., 1984; PKI(14–24)amide, Cheng et al., 1986) did not interfere with CGS 21680. Since, both PMA and staurosporine left the effect of CGS 21680 unaltered, the involvement of protein kinase C in the signal transduction mechanism of A2A receptors may also be excluded.

It is noteworthy that the activation of protein kinase A inhibited, while the activation of protein kinase C did not alter the CGS 21680-induced inhibition of NMDA currents. This may be due to the fact that dibutyryl cyclic AMP and Sp-cyclic AMPS increase the conductance of NMDA receptor channels, while CGS 21680, although by a different mechanism, decrease it. The net effect is an antagonism.

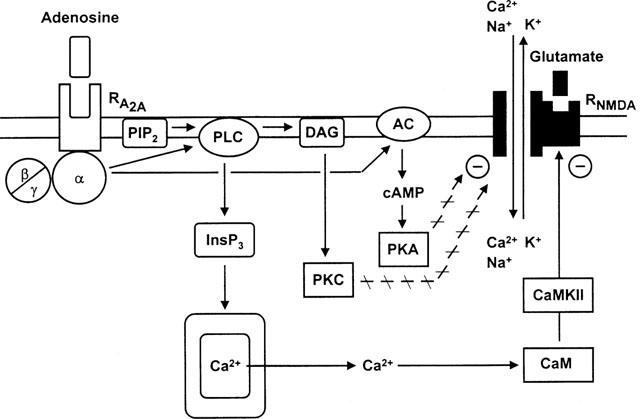

Striatal adenosine A2A receptors may modulate NMDA receptor channels via the phospholipase C/InsP3/calmodulin and calmodulin kinase II pathway. Since an inhibitor of phospholipase C, U-73122 (Smith et al., 1990) abolished, while the inactive analogue U-73343 (Smith et al., 1990) did not alter the effect of CGS 21680 on NMDA currents, as a first step in the sequence of events, A2A receptor stimulation may lead to a G protein-mediated activation of phospholipase C. Furthermore, heparin, which can compete with InsP3 for its specific binding site (Worley et al., 1987) interfered with the CGS 21680-induced inhibition; a more efficient buffering of intracellular Ca2+ by substituting BAPTA for EGTA had the same effect as heparin.

Hence, the activation of phospholipase C may release intracellular Ca2+ via the generation of InsP3 (Berridge & Irvine, 1989). Ample evidence indicates that NMDA receptors occur in clusters anchored in the plasma membrane (Whatley & Harris, 1996); specifically the binding of the NR1 subunit to actin via α-actinin-2 is essential for interaction with the cytoskeleton and an intact receptor function (Wyszynski et al., 1997). Therefore, Ca2+-dependent rundown of NMDA receptor channels (Legendre et al., 1993) which is facilitated by cytochalasin B-evoked enhancement of actin depolimerization (Rosenmund & Westbrook, 1993) may be due to a competitive displacement of α-actinin-2 from the NR1 subunit of the receptor by Ca2+/calmodulin (Wyszynski et al., 1997). In excellent agreement with these results both the calmodulin antagonist W-7 (Tanaka et al., 1993) and cytochalasin B abolished the CGS 21680-induced inhibition of NMDA currents.

However, in addition to a direct effect of calmodulin via its binding site at the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor channel, Ca2+/calmodulin may also act via calmodulin kinase II and subsequent phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit (Omkumar et al., 1996). In support of this assumption, two inhibitors of calmodulin kinase II, CaM kinase II(281–309) (Ishida et al., 1995) and KN-93 (Sumi et al., 1991) but not the inactive structural analogue KN-92 abolished the effect of CGS 21680. Although the sites for phosphorylation by CaM kinase II have been unequivocally identified (Omkumar et al., 1996), it is not yet known how this affects the function of NMDA receptors (Chandler et al., 1998). Our own results suggest that A2A receptor stimulation may activate CaM kinase II which subsequently causes a conductance decrease for cations through NMDA receptor channels.

It has recently been shown that increases in the activity of calcineurin (Lieberman & Mody, 1994), a major Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, can antagonize the effect of protein kinase A to tonically phosphorylate NMDA receptor channels and, thereby, to increase their conductance (Raman et al., 1996). However, in the present experiments calcineurin did not appear to mediate the interaction between A2A and NMDA receptors, since the calcineurin inhibitor deltamethrin (Enan & Matsumura, 1992) failed to antagonize the effect of CGS 21680. Finally, neither deltamethrin nor KN-93 altered the NMDA-induced current, when given alone. Hence, a tonic control of NMDA receptor channels by calcineurin or CaM kinase II is unlikely.

In conclusion, adenosine A2A receptors are present at the striatopallidal subset of medium spiny neurons, where they inhibit the conductance of NMDA, but not AMPA receptor channels (Figure 8). The transduction mechanism is the phospholipase C/InsP3/calmodulin and calmodulin kinase II pathway. The adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A and the diacylglycerol/protein kinase C pathways are not involved in this effect. Medium spiny neurons of the striatum contribute to two divergent efferent pathways to the basal ganglia output nuclei (internal segment of the globus pallidus and substantia nigra pars reticularis; Parent & Hazrati, 1993; Latini et al., 1996). A direct route is formed by the substance P positive cells and an indirect route by the enkephalin positive cells; this latter loop consists additionally of neurons in the external segment of the globus pallidus projecting to the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and fibres connecting the STN with the output nuclei (Parent & Hazrati, 1993; Latini et al., 1996). Activity in the direct pathway facilitates, whereas activity in the indirect pathway depresses locomotor behaviour. Hence, agonists at striatal A2A receptors may selectively interfere with EAA neurotransmission from corticostriatal fibres onto enkephalin-containing medium spiny neurons and may, thereby, alleviate locomotor depression, e.g. in Parkinson's disease. However, an alternative effect of A2A receptor activation may be the aggravation of locomotor depression via an antagonistic interaction with D2 dopamine receptors also situated at enkephalin-containing medium spiny neurons (Ferré et al., 1993; Ongini & Fredholm, 1996; Richardson et al., 1997). Hence, the net effect of adenosine may depend on the balance between these opposing modulatory functions.

Figure 8.

Transduction mechanisms of adenosine A2A receptors to inhibit the conductance of NMDA receptor channels in striatal neurons. The release of intracellular Ca2+ from its pool by stimulation of A2A receptors (via the G protein/phospholipase C/inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate cascades) led to the activation of calmodulin/calmodulin kinase II and the subsequent inhibition of NMDA receptor channels both by a direct binding of calmodulin to the NR1 subunit and by phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit. The stimulation by NMDA of its receptor allows Na+ and Ca2+ to enter and K+ to leave the cell interior. The diacylglycerol/protein kinase C cascade and the adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A cascade are not involved in the transduction mechanism of A2A receptors. α, β, γ, subunits of G proteins; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-diphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; InsP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; CaM, calmodulin; CaMK-II, calmodulin kinase II; DAG, diacylglycerol; PKC, protein kinase C; AC, adenylate cyclase; cAMP, cyclic AMP; PKA, protein kinase A; –, inhibition of the channel.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr J Grosche for help with the confocal microscopy and to Dr J. Linden for the supply of an A2A receptor antibody. This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (II 20/7-1) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung, Forschung und Technologie, Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung an der Medizinischen Fakultät Leipzig (01KS9504, C4).

Abbreviations

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AMPA

(S)-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- CaM kinase II

calmodulin kinase II

- CGS 21680

2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- CNS

central nervous system

- EAA

excitatory amino acid

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- InsP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- NGS

normal goat serum

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- TBS

Tris buffered saline

References

- ANGULO J.A., MCEWEN B.S. Molecular aspects of neuropeptide regulation and function in the corpus striatum and nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. Rev. 1994;19:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRY P.H. JPCalc, a software package for calculating liquid junction potential corrections in patch-clamp, intracellular, epithelial and bilayer measurements and for correcting junction potential measurements. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1994;51:107–116. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEN-ARI Y., ANIKSZTEJN L., BREGESTOVSKI P. Protein kinase C modulation of NMDA currents: an important link for LTP induction. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:333–339. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90049-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERRIDGE M.J., IRVINE R.F. Inositol phosphates and cell signalling. Nature. 1989;341:197–205. doi: 10.1038/341197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISHOP G.A., CHANG H.T., KITAI S.T. Morphological and physiological properties of neostriatal neurons: an intracellular horseradish peroxidase study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1982;7:179–191. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALABRESI P., MERCURI N., STANZIONE P., STEFANI A., BERNARDI G. Intracellular studies on the dopamine-induced firing inhibition of neostriatal neurons in vitro: evidence for D1 receptor involvement. Neuroscience. 1987;20:757–771. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTAGNA M., TAKAI Y., KAIBUCHI K., SANO K., KIKKAWA U., NISHIZUKA Y. Direct activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase by tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:7847–7851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANDLER L.J., HARRIS R.A., CREWS F.T. Ethanol tolerance and synaptic plasticity. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:491–495. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG H.-C., KEMP B.E., PEARSON R.B., SMITH A.J., MISCONI L., VAN PATTEN S.M., WALSH D.A. A potent synthetic peptide inhibitor of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:989–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHERUBINI E., HERRLING P.L., LANFUMEY L., STANZIONE P. Excitatory amino acids in synaptic excitation of rat striatal neurones in vitro. J. Physiol. 1988;400:677–690. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CREPEDA C., COLWELL C.S., ITRI J.N., CHANDLER S.H., LEVINE M.S. Dopaminergic modulation of NMDA-induced whole cell currents in neostriatal neurons in slices: contribution of calcium conductances. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:82–94. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI CHIARA G., MORELLI M., CONSOLO S. Modulatory functions of neurotransmitters in the striatum: ACh/dopamine/NMDA interactions. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:228–233. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS F.A., KONNERTH A., SAKMANN B., TAKAHASHI T. A thin slice preparation for patch clamp recordings from neurones of the mammalian central nervous system. Pflügers Arch. 1989;414:600–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00580998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENAN E., MATSUMURA F. Specific inhibition of calcineurin by types II synthetic pyrethroid insecticides. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;43:1777–1784. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90710-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATIMA-SHAD K., BARRY P.H. Anion permeation in GABA- and glycine-gated channels of mammalian cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1993;253:69–75. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1993.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRÉ S., O'CONNOR W.T., FUXE K., UNGERSTEDT U. The striatopallidal neuron: a main locus for adenosine-dopamine interactions in the brain. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:5402–5406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05402.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., ABBRACCHIO M.P., BURNSTOCK G., DALY J.W., HARDEN T.K., JACOBSON K.A., LEFF P., WILLIAMS M. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEIGER J.D., NAGY J.I.Adenosine deaminase and [3H]nitrobenzylthioinosine as markers of adenosine metabolism and transport in central purinergic systems Adenosine and adenosine receptors 1990Clifton: Humana Press; 225–287.Williams, M. (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- GEREVICH Z., WIRKNER K., FRANKE H., ILLES P. Inhibition by adenosine A2A receptors of the NMDA component of excitatory synaptic currents in rat striatopallidal neurons. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;361:R34. [Google Scholar]

- GREENGARD P., JEN J., NAIRN A.C., STEVENS C.F. Enhancement of the glutamate response by cAMP-dependent protein kinase in hippocampal neurons. Science. 1991;253:1135–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1716001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIDA A., KAMESHITA I., OKUNO S., KITANI T., FUJISAWA H. A novel, highly specific and potent inhibitor of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;212:806–812. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON K.A. Specific ligands for the adenosine receptor family. Neurotransmission. 1996;12:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON K.A., NIKODIJEVIC O., PADGETT W.L., GALLO-RODRIGUEZ C., MAILLARD M., DALY J.W. 8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine (CSC) is a selective A2-adenosine antagonist in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81466-d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARVIS M.F., SCHULZ R., HUTCHINSON A.J., DO U.H., SILLS M.A., WILLIAMS M. [3H]CGS 21680, a selective A2 adenosine receptor agonist directly labels A2 receptors in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIANG Z.-G., NORTH R.A. Membrane properties and synaptic responses of rat striatal neurones in vitro. J. Physiol. 1991;443:533–553. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LATINI S., PAZZAGLI M., PEPEU G., PEDATA F. A2 adenosine receptors: their presence and neuromodulatory role in the central nervous system. Gen. Pharmac. 1996;27:925–933. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(96)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEGENDRE P., ROSENMUND C., WESTBROOK G.L. Inactivation of NMDA channels in cultured hippocampal neurons by intracellular calcium. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:674–684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00674.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIEBERMAN D.N., MODY I. Regulation of NMDA channel function by endogenous Ca2+-dependent phosphatase. Nature. 1994;369:235–239. doi: 10.1038/369235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDEN D.J., CONNOR J.A. Participation of postsynaptic PKC in cerebellar long-term depression in culture. Science. 1991;254:1656–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.1721243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LLANO I., MARTY A., ARMSTRONG C.M., KONNERTH A. Synaptic- and agonist-induced excitatory currents of Purkinje cells in rat cerebral slices. J. Physiol. 1991;434:183–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOHSE M.J., KLOTZ K.-N., SCHWABE U., CRISTALLI G., VITTORI S., GRIFANTINI M. 2-Chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine: a highly selective agonist at A1 adenosine receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1988;337:687–689. doi: 10.1007/BF00175797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUPICA C.R., CASS W.A., ZAHNISER N.R., DUNWIDDIE T.V. Effects of the selective adenosine A2 receptor agonist CGS 21680 on in vitro electrophysiology, cAMP formation and dopamine release in rat hippocampus and striatum. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;252:1134–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYFIELD R.D., SUZUKI F., ZAHNISER N.R. Adenosine A2A receptor modulation of electrically evoked endogenous GABA release from slices of rat globus pallidus. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:2334–2337. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORI A., SHINDOU T., ICHIMURA M., NONAKA H., KASE H. The role of adenosine A2A receptors in regulating GABAergic synaptic transmission in striatal medium spiny neurons. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:605–611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00605.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOSS S.J., SMART T.G. Modulation of amino acid-gated ion channels by protein phosphorylation. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1996;39:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NÖRENBERG W., WIRKNER K., ASSMANN H., RICHTER M., ILLES P. Adenosine A2A receptors inhibit the conductance of NMDA receptor channels in rat neostriatal neurons. Amino Acids. 1998;14:33–39. doi: 10.1007/BF01345239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NÖRENBERG W., WIRKNER K., ILLES P. Effect of adenosine and some of its structural analogues on the conductance of NMDA receptor channels in a subset of rat neostriatal neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:71–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLAH M.E., STILES G.L. Adenosine receptor subtypes: characterization and therapeutic regulation. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995;35:581–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.003053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OMKUMAR R.V., KIELY M.J., ROSENSTEIN A.J., MIN K.-T., KENNEDY M.B. Identification of a phosphorylation site for calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31670–31678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONGINI E., FREDHOLM B.B. Pharmacology of adenosine A2A receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996;17:364–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARENT A., HAZRATI L.-N. Anatomical aspects of information processing in primate basal ganglia. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK M.R., LIGHTHALL J.W., KITAI S.T. Recurrent inhibition in the rat neostriatum. Brain Res. 1980;194:359–369. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATERSON A.R.P., BABB L.R., PARAN J.H., CASS C.E. Inhibition by nitrobenzylthioinosine of adenosine uptake by asynchronous HeLa cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1977;13:1147–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMAN I.M., TONG G., JAHR C.E. β-Adrenergic regulation of synaptic NMDA receptors by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron. 1996;16:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICHARDSON P.J., KASE H., JENNER P.G. Adenosine A2A receptor antagonists as new agents for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:338–344. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENMUND C., WESTBROOK G.L. Calcium-induced actin depolymerization reduces NMDA channel activity. Neuron. 1993;10:805–814. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90197-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFMANN S.N., JACOBS O., VANDERHAEGHEN J.-J. Striatal restricted adenosine A2 receptor (RCD8) is expressed by enkephalin but not by substance P neurons: an in situ hybridization histochemistry study. J. Neurochem. 1991;57:1062–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEBASTIAO A.M., RIBEIRO J.A. Adenosine A2 receptor-mediated excitatory actions on the nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 1996;48:167–189. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH A.D., BOLAM J.P. The neural network of the basal ganglia as revealed by the study of synaptic connections of identified neurones. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:259–265. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90106-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH R.J., SAM L.M., JUSTEN J.M., BUNDY G.L., BALA G.A., BLEASDALE J.E. Receptor-coupled signal transduction in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils: effects of a novel inhibitor of phospholipase C-dependent processes on cell responsiveness. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;253:688–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERNWEIS P.C., PANG I.-H. The G protein-channel connection. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:122–126. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90002-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUMI M., KIUCHI K., ISHIKAWA T., ISHII A., HAGIWARA M., NAGATSU T., HIDAKA H. The newly synthetized selective Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II inhibitor KN-93 reduces dopamin contents in PC12h cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;181:968–975. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)92031-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWOPE S.L., MOSS S.J., BLACKSTONE C.D., HUGANIR R.L. Phosphorylation of ligand-gated ion channels: a possible mode of synaptic plasticity. FASEB J. 1992;6:2514–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA T., OHMURA T., HIDAKA H. Calmodulin antagonists' binding sites on calmodulin. Pharmacology. 1983;26:249–257. doi: 10.1159/000137808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TINGLEY W.G., EHLERS M.D., KAMEYAMA K., DOHERTY C., PTAK J.B., RILEY C.T., HUGANIR R.L. Characterization of protein kinase A and protein kinase C phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR1 subunit using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:5157–5166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRIVEDI B.K., BRIDGES A.J., PATT W.C., PRIEBE S.R., BRUNS R.F. N6-bicycloalkyladenosine with unusually high potency and selectivity for the adenosine A1 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:8–11. doi: 10.1021/jm00121a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN HAASTERT P.M., VAN DRIEL R., JASTORFF B., BARANIAK J., STEC W.J., DE WITT R.J.W. Competitive cAMP antagonists for cAMP-receptor proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:10020–10024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHATLEY V.J., HARRIS R.A. The cytoskeleton and neurotransmitter receptors. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1996;39:113–143. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILKINSON S.E., HALLAM T.J. Protein kinase C: is its pivotal role in cellular activation over-stated. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORLY P.F., BARABAN J.M., SUPATTAPONE S., WILSON V.S., SNYDER S.H. Characterization of inositol trisphosphate receptor binding in brain. Regulation by pH and calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:12132–12136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WYSZYNSKI M., LIN J., RAO A., NIGH E., BEGGS A.H., CRAIG A.M., SHENG M. Competitive binding of α-actinin and calmodulin to the NMDA receptor. Nature. 1997;385:439–442. doi: 10.1038/385439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]