Abstract

The effects of A2 adenosine receptor agonists upon phenylephrine-stimulated contractility in preparations of rat epididymis were investigated.

Preparations responded to phenylephrine (3 μM) with submaximal contractions. Adenosine and the stable agonists 5′-N-ethylcarboxamido-adenosine (NECA) and 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl) phenethylamino-N-ethylcarboxamide adenosine (CGS 21680) inhibited phenylephrine-induced contractions (potency order, NECA>CGS 21680>adenosine). The A2A receptor-selective antagonist, 4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]-triazolo-[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol (ZM 241385, 30 μM) blocked the response to NECA.

The A2A adenosine receptor-mediated inhibitory responses to NECA were reduced by the KATP channel blocker, glibenclamide (3 μM) and abolished by charybdotoxin (100 nM).

The diterpene forskolin elicited a concentration-dependent inhibition of phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated contractility (by 62±8% of control at 100 μM). Charybdotoxin (100 nM), but not glibenclamide (3 μM) blocked the forskolin (10 μM) inhibition of phenylephrine-stimulated contractility.

NECA elicited concentration-dependent increases in both cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP accumulation which were antagonized by ZM 241385 (30 nM).

The protein kinase G activator, APT-cyclic GMP (8-(-Aminophenylthio) guanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate) and the protein kinase A activator (Sp)-8-bromoadenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate (Sp-8-Br-cyclic AMPs), inhibited phenylephrine (3 μM) induced contractions of rat epididymis. Glibenclamide (3 μM), but not charybdotoxin (100 nM), inhibited ATP-cyclic GMP responses. Charybdotoxin (100 nM), but not glibenclamide (3 μM) reduced the effect of Sp-8-Br-cyclic AMPs.

This study shows that the A2A adenosine receptor inhibition of epididymal contractility may be mediated through the activation of charybdotoxin- and glibenclamide-sensitive potassium channels and may involve the activation of both protein kinases A and G.

Keywords: A2A adenosine receptor, rat epididymis, protein kinase G, KATP channels, cyclic GMP

Introduction

In previous studies A2 adenosine receptor activation has been shown to inhibit contractility in both the epididymis of the guinea-pig (Haynes et al., 1998) and in the vas deferens of the rat (Brownhill et al., 1996). Although these studies have clearly shown that post-junctional A2 adenosine receptors modulate the contractility of urogenital tract smooth muscle, the mechanisms through which these receptors elicit their effects are unclear. In the epididymis of the guinea-pig, A2 adenosine receptors raise intracellular cyclic AMP (Haynes et al., 1998), a finding compatible with the generally accepted view that A2 adenosine receptors are Gs-protein coupled and activate adenylyl cyclase to increase intracellular cyclic AMP (Fredholm et al., 1994). More recent reports have demonstrated that A2 adenosine receptor activation, via the activation of adenylyl cyclase and the resulting increase in intracellular cyclic AMP, can stimulate cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (Kleppisch & Nelson, 1995), and that protein kinases can also modulate potassium channel activity (Kleppisch & Nelson, 1995; Barrett-Jolley et al., 1996). This is consistent with evidence that, in non-urogenital tract smooth muscle, adenosine receptor effects can be mediated through the modulation of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels (Marshall et al., 1993; Dart & Standen, 1993; Hadjkaddour et al., 1996; Sabates et al., 1997; Sheridan et al., 1997). Given these findings, the purpose of the current study was to investigate the possibility that epididymal A2 adenosine receptors relax smooth muscle by stimulating a cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase to open K+ channels.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (180–280 g) were killed by decapitation or exsanguination following anaesthesia (methohexitone 10 mg ml−1; amobarbital 40 mg ml−1), in accordance with the Monash University Standing Committee Guidelines on Animal Experimentation. On the day of use the cauda epididymis was removed and unravelled with the aid of a Leica binocular dissecting microscope.

Tissue preparation

Preparations of cauda epididymis (approximately 1 cm long) were placed into modified Krebs solution (of composition, mM; NaCl 118; KCl 4.7; MgSO4 0.45; K2HPO4 2.5; NaHCO3 25; CaCl2 1.9; glucose 11) at 35°C, aerated with carbogen (O2 : CO2; 95 : 5), and used for either contractility or cyclic nucleotide accumulation studies.

Contractility studies

Preparations of cauda epididymis were attached, with a silk thread (2/0) to a stainless steel tissue holder. The upper end of each preparation was connected, via, another silk thread, to a Grass FTO3 force-displacement transducer. Preparations of cauda epididymis were suspended under an initial resting force of approximately 0.5 g in 2 ml tissue baths containing modified Krebs solution (35°C, bubbled with carbogen)–preparations were re-tensioned (to 0.5 g) twice more at 15 min intervals. Recordings of contractile force were made using a MacLab analogue to digital recording system (ADInstruments, Australia). Under these conditions the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine elicited concentration-dependent increases in contractile force, as has been shown previously in guinea-pig epididymis (Haynes & Hill, 1996). Thus, in the present study we measure the increase in contractile force following the addition of 3 μM phenylephrine (in the absence or presence of adenosine receptor agonists or protein kinase activators). To minimize possible heterogeneity along the length of cauda epididymis, sections of tissue were randomly assigned within each experimental paradigm. Following a 45 min equilibration period preparations were stimulated with phenylephrine (3 μM; for 120 s or until the maximal contractile response was achieved), and then washed (three times) with fresh Krebs solution. Preparations were left for 14 min before the next addition of phenylephrine (3 μM). Prior to subsequent additions of phenylephrine, preparations received either adenosine receptor agonists, forskolin, protein kinase activators, K+ channel blockers or K+ channel activators. The adenosine receptor agonists and forskolin were added 120 s prior to phenylephrine (Haynes et al., 1998). Protein kinase activators were added at least 10 min prior to phenylephrine, this time frame has previously been shown to be appropriate for activation of protein kinase (van der Zypp & Majewski, 1998). Neither glibenclamide (3 μM), ODQ (1 μM), DPCPX (100 nM), ZM 241385 (30 nM), or charybdotoxin (100 nM) had any significant effect upon phenylephrine (3 μM)-induced contractility (n=7–14, data not shown).

Preliminary studies using the A1 adenosine receptor-selective agonist (S)-ENBA indicated the presence of contraction-eliciting A1 adenosine receptors (n=4, data not shown). To minimize agonist effects at A1 adenosine receptors all experiments with adenosine receptor agonists were undertaken in the presence of the A1 adenosine receptor selective antagonist, DPCPX (100 nM, as used previously Haynes et al., 1998).

Cyclase activation assays

Cyclic GMP and cyclic AMP were assayed using commercially available kits (Amersham, TRK 500 and TRK 432 respectively). The preparation of tissues was similar to that used previously (Haynes et al., 1998), briefly, preparations of epididymis were obtained, as described above, and incubated for 30 min in (90 μl) modified Krebs solution (at 35°C, under a carbogen atmosphere). Following this equilibration period preparations were washed with fresh modified Krebs solution containing DPCPX (100 nM) and the phosphodiesterase inhibitors M&B 29948 (30 μM for cyclic GMP assays) or rolipram (30 μM for cyclic AMP assays) and incubated for a further 20 min. Following this period NECA or vehicle were added to preparations, 5 min later phenylephrine (3 μM) was added to each preparation and the incubation continued for a further 5 min. Concentrated HCl (5% of final incubation volume) was added to stop the reaction and the tissues frozen (−20°C for up to 1 week). On the day of use the tissue incubation medium was neutralized with NaOH and the cyclic nucleotide content assayed by the method described within the kit.

Analysis and statistics

Responses to each addition of phenylephrine (± adenosine receptor agonists, protein kinase activators, antagonist or vehicle controls) were expressed as a percentage of their own initial response to phenylephrine. To remove clutter from Figures 1, 2 and 3, 6 and 7, inhibitory responses are shown as the difference between adenosine receptor agonists or protein kinase activators and their respective animal-matched antagonist or inhibitor controls. Estimates of pEC50, slope and maximum contractile response were generated using a four-parameter logistic curve fitting and graphics program PRISM v2.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, U.S.A.). Raw data points were compared with a Student's t-test, one-way ANOVA or Dunnett's test. Concentration-response curves were compared with an iterative curve fitting program, FLEXIFIT (see Guardabasso et al., 1988), significant changes were determined with an F-test. P<0.05 was taken as the level of significance for all statistical analysis.

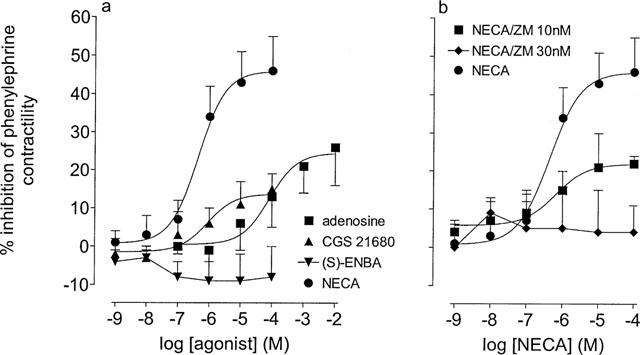

Figure 1.

Effects of the adenosine receptor agonists and the A2A adenosine receptor antagonist ZM 241385 upon phenylephrine-stimulated contractility in the epididymis of the rat. (a) The effects of NECA, CGS 21680, adenosine and (S)-ENBA upon responses to phenylephrine (3 μM). (b) The effects of ZM 241385 (ZM, 10 and 30 nM) upon the NECA-inhibition of phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated contractility. The Y-axis shows the difference between time control responses and responses to adenosine receptor agonist addition. All experiments were undertaken in the presence of the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, DPCPX (100 nM). Bars represent s.e.mean (some omitted for clarity) of 6–24 experiments.

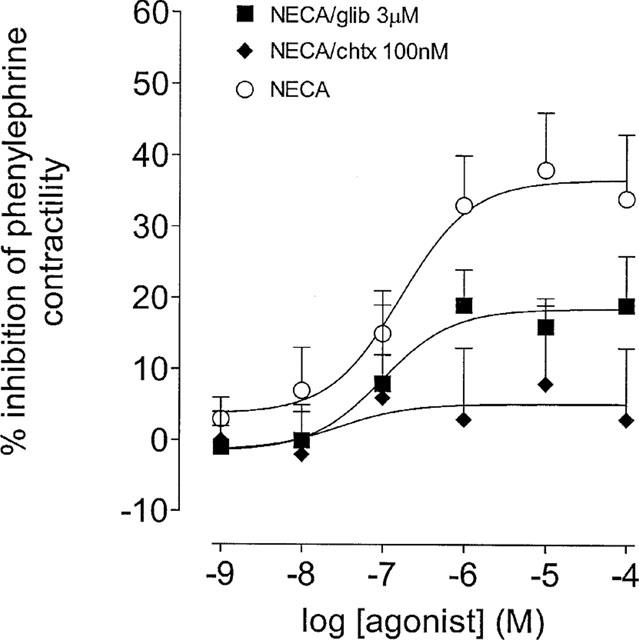

Figure 2.

Effects of glibenclamide and charybdotoxin upon the inhibition of phenylephrine (3 μM)-induced contractility by NECA in the epididymis of the rat. This panel shows concentration-response curves to NECA constructed in the absence and presence of either glibenclamide (glib, 3 μM) or charybdotoxin (chtx, 100 nM). The Y-axis shows the difference between time control responses and responses to adenosine receptor agonist addition. All experiments were undertaken in the presence of the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, DPCPX (100 nM). Bars represent s.e.mean (some omitted for clarity) of 6–7 experiments.

Figure 3.

Effects of the soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor, ODQ, upon responses to NECA in the epididymis of the rat. This panel shows concentration-response curves to NECA constructed in the absence and presence of ODQ (1 μM). The Y-axis shows the difference between time control responses and responses to adenosine receptor agonist addition. All experiments were undertaken in the presence of the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, DPCPX (100 nM). Bars represent s.e.mean (some omitted for clarity) of seven experiments.

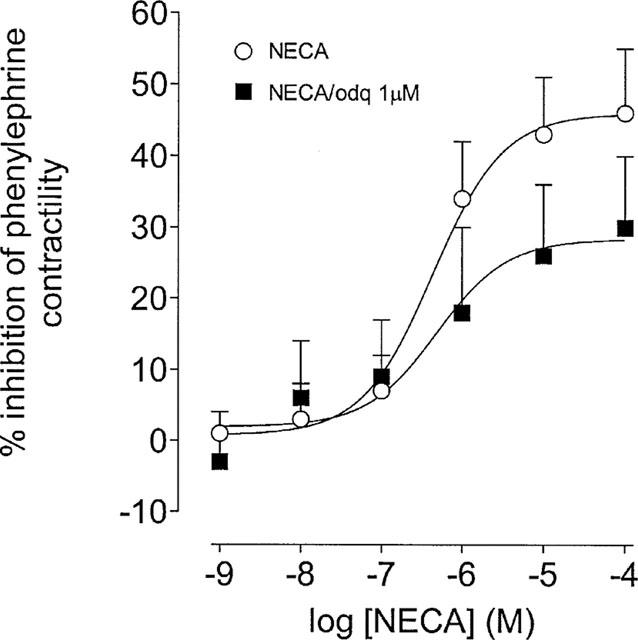

Figure 6.

Effects of glibenclamide and charybdotoxin upon responses to Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (Sp-) in the phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated epididymis of the rat. (a) Responses to Sp- in the absence and presence glibenclamide (glib, 3 μM). (b) Responses to Sp- in the absence and presence charybdotoxin (chtx, 100 nM). The Y-axis shows the difference between time control responses and responses to adenosine receptor agonist addition. All experiments were undertaken in the presence of the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, DPCPX (100 nM). Bars represent s.e.mean (some omitted for clarity) of 6–10 experiments.

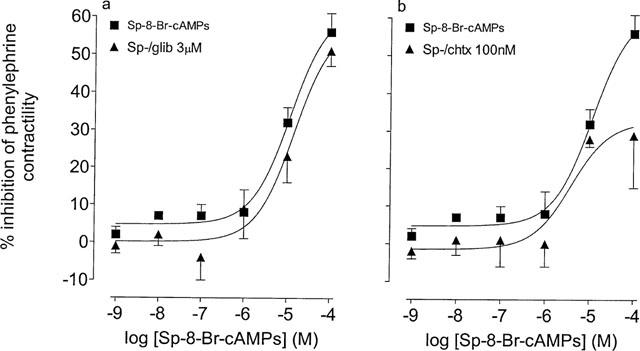

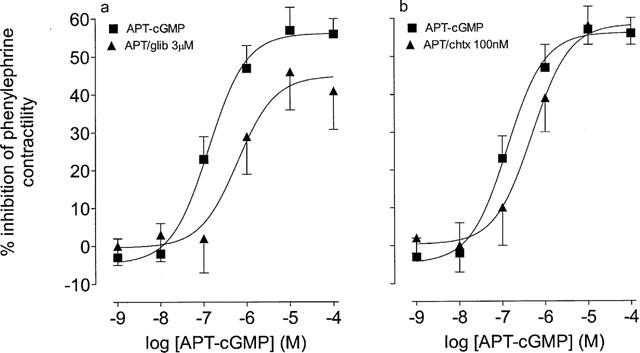

Figure 7.

Effects of glibenclamide and charybdotoxin upon responses to APT-cGMP in the phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated epididymis of the rat. (a) Responses to APT-cGMP in the absence and presence glibenclamide (glib, 3 μM). (b) Responses to APT-cGMP in the absence and presence charybdotoxin (chtx, 100 nM). The Y-axis shows the difference between time control responses and responses to adenosine receptor agonist addition. All experiments were undertaken in the presence of the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, DPCPX (100 nM). Bars represent s.e.mean (some omitted for clarity) of 6–8 experiments.

Drugs

2-p-(2-carboxyethyl) phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS 21680), (2S)-N6-[2-endo-norbornyl]adenosine ((S)-ENBA), 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), diazoxide and tetraethylammonium were from Research Biochemicals Inc., U.S.A.; 5′-N-ethylcarboxamido- adenosine (NECA), forskolin and phenylephrine HCl were from Sigma Chemical Co., U.K.; 4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol (ZM 241385), 1H-[1,2,4]-Oxadiazol[4,3-A]quinoxaline-1-one (ODQ) and rolipram were from Tocris Cookson Ltd, U.K. 8-(-Amino-phenylthio) guanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (APT-cGMP) and (Sp)-8-bromoadenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate (Sp-8-Br-cAMPs) were from Biolog Life Science Institute, GmbH. Charybdotoxin (Auspep, Australia). M&B 29948 was a gift from May & Baker, Australia.

Adenosine receptor ligands and forskolin were made up as a stock solution in DMSO, aliquoted and frozen. All other drugs were dissolved, in distilled water, aliquoted and frozen. Charybdotoxin was made up as a stock in 150 mM NaCl, aliquoted and frozen. On the day of use all drugs made up to volume in buffer. In no case did DMSO vehicle exceed 0.1% of the tissue bath volume.

Results

Effects of adenosine receptor agonists

In the presence of the A1 adenosine receptor selective antagonist, DPCPX (100 nM) phenylephrine (3 μM)-induced contractions could be inhibited by adenosine, by the non-selective and stable adenosine analogue, NECA and also by the A2A adenosine receptor-selective analogue CGS 21680. The maximum response to CGS 21680 was reduced (P<0.05, F-test, d.f.=1,118) compared to that of NECA. The A1 adenosine receptor selective agonist, (S)-ENBA was without effect. The rank order of agonist potency for this inhibition was NECA>CGS 21680>adenosine (Figure 1a).

The A2A receptor-selective antagonist, ZM 241385 (10 and 30 nM), reduced and then abolished the NECA-inhibition of phenylephrine-induced contractions, respectively (Figure 1b).

The ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel blocker, glibenclamide (3 μM), significantly reduced the maximal effect of NECA (P<0.05, F-test, d.f.=1,114; Figure 2). Increasing the concentration of glibenclamide 10 fold did not further reduce responses to NECA (n=6, data not shown). The Ca2+-activated and delayed rectifier K+ channel blocker, charybdotoxin (100 nM) blocked the response to NECA (Figure 2). The non-selective K+ channel blocker, tetraethylammonium (1 mM) also blocked responses to NECA (n=6, data not shown).

The soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (1 μM; Moro et al., 1996) reduced the maximal response to NECA (P<0.05, F-test, d.f.=1,113; Figure 3).

Effects of forskolin

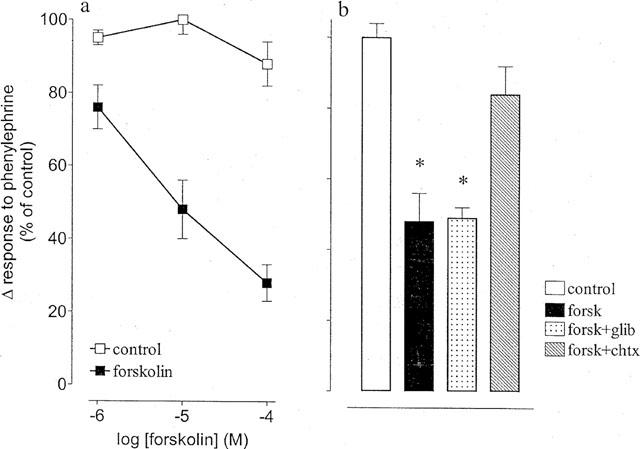

Forskolin inhibited phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated contractility in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4a). The inhibitory effect of forskolin (10 μM) was attenuated by charybdotoxin (100 nM), but not by glibenclamide (3 μM; Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Effects of glibenclamide and charybdotoxin upon responses to forskolin in the epididymis of the rat. (a) Responses to forskolin compared to time control responses. (b) Responses to forskolin (10 μM) in the absence and presence of charybdotoxin (chtx, 100 nM) or glibenclamide (glib, 3 μM). The Y-axis shows the percentage change in responses to phenylephrine from initial responses. Bars represent s.e.mean (some omitted for clarity) of six experiments. *Indicates a significant difference (P<0.05, Dunnett's test).

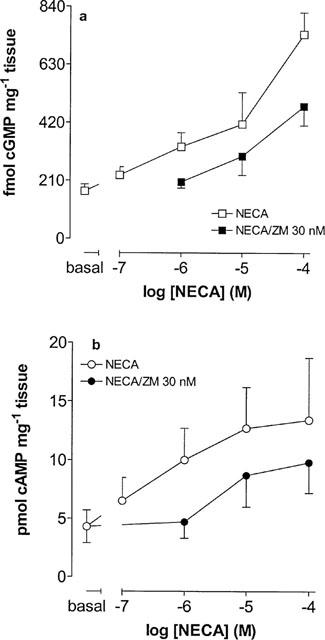

Agonist effects upon cyclase activity

In the presence of DPCPX (100 nM) NECA stimulated both cyclic GMP and cyclic AMP accumulation in preparations of the cauda epididymis of the rat, effects antagonized by ZM 241385 (30 nM; Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

The effects of NECA upon cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP accumulation in preparations of the cauda epididymis of the rat. (a) The effects of NECA upon cyclic AMP accumulation in the absence and presence of ZM 241386 (ZM, 30 nM). (b) The effects of NECA upon cyclic GMP accumulation in the absence and presence of ZM 241386 (ZM, 30 nM). Bars represent s.e.mean (some omitted for clarity) of 8–10 experiments.

Effects of protein kinase activation and diazoxide

The protein kinase A activator, Sp-8-Br-cAMPs inhibited the contractile response of phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated epididymis, this effect was not inhibited by glibenclamide (3 μM), but was significantly (P<0.05, F-test, d.f.=1,52) reduced by charybdotoxin (100 nM; Figure 6a,b).

The protein kinase G activator, APT–cGMP also inhibited the contractile response of phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated epididymis, this effect was significantly (P<0.05, F-test, d.f.=1,70) reduced by glibenclamide (3 μM), but not charybdotoxin (100 nM; Figure 7a,b).

The KATP channel opener, diazoxide (300 μM), reduced the phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated contractile response of the rat epididymis to 54±9% of the phenylephrine-only time control (n=4, data not shown). In the presence of charybdotoxin (100 nM), diazoxide (300 μM) reduced the phenylephrine (3 μM)-stimulated responses of the rat epididymis to 58±7% of the phenylephrine-only time control response (n=4, data not shown).

Discussion

In an earlier study we demonstrated that A2A adenosine receptors inhibited the contractility of epididymal smooth muscle (Haynes et al., 1998). Similarly in this study adenosine receptor agonists NECA, CGS 21680 and adenosine all reduced phenylephrine-stimulated contractions in the epididymis of the rat. The rank order of adenosine receptor agonist potency inhibiting contractility of the rat cauda epididymis, and the high potency of the A2A adenosine receptor agonist ZM 241385 (Poucher et al., 1995) in antagonizing this effect are consistent with an action at A2A adenosine receptors (Fredholm et al., 1994). The finding that CGS 21680 elicited a smaller maximal effect, compared to that of NECA, is consistent with previously reported findings (Prentice & Hourani, 1996; Haynes et al., 1998) and may indicate that this is a partial agonist at A2A adenosine receptors.

In previous studies it has been shown that adenosine receptor effects upon smooth muscle are mediated through opening of KATP channels (Marshall et al., 1993; Dart & Standen, 1993; Sabates et al., 1997), although some workers suggest KATP channel-independent adenosine receptor-effects (Dunker et al., 1995; Haynes et al., 1995). The possibility of potassium channel involvement in the NECA-mediated inhibition of contractility responses in the rat epididymis was investigated using the potassium channel blockers glibenclamide and charybdotoxin. In this tissue the NECA-mediated inhibition of phenylephrine-stimulated contractility was partially blocked by the KATP channel-blocking drug, glibenclamide and abolished by charybdotoxin, indicating roles for both glibenclamide- and charybdotoxin-sensitive potassium channels. These data are consistent with evidence showing that A2 adenosine receptors interact with KATP channels to relax skeletal (Barrett-Jolley et al., 1996), airway (Kleppisch & Nelson, 1995; Hadjkaddour et al., 1996; Sheridan et al., 1997) and vascular smooth muscle (Akatsuka et al., 1994). However, further investigation of the K+ channel dependent mechanisms of epididymal smooth muscle showed that the adenylyl cyclase activator, forskolin, also inhibited epididymal smooth muscle contractility and that this effect was sensitive to charybdotoxin, but not glibenclamide. These data are not unusual since forskolin effects upon K+ channels have been widely investigated in other systems, with mixed results. Thus forskolin effects have been shown to be blocked (Nakashima & Vanhoutte, 1995; Chang, 1997; Wellman et al., 1998) or unaffected by glibenclamide (Huang & Kwok, 1997; Sheridan et al., 1997). Similarly, forskolin-mediated effects have been shown to be both charybdotoxin sensitive (Hiramatsu et al., 1994) and insensitive (Nakashima & Vanhoutte, 1995). In the epididymal smooth muscle of the rat the charybdotoxin-sensitive inhibitory responses appear cyclic AMP dependent, leading to the hypothesis that the stimulation of A2A adenosine receptors elevates intracellular cyclic AMP levels, which in turn activates protein kinase A opening charybdotoxin-sensitive K+ channels, leading to inhibition of smooth muscle contractility. This hypothesis is not inconsistent with recent evidence indicating a cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation of Ca2+ dependent K+ channels (see Brayden, 1996; Standen & Quayle, 1998).

There are however, some additional findings to consider such as the NECA stimulated increase in both cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP levels. The mechanism underlying this latter effect is unclear, that it involves guanylate cyclase is evident from the inhibition of NECA responses by the soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor, ODQ (Moro et al., 1996). There are conflicting reports that A2 adenosine receptor vasorelaxant effects are mediated through the indirect stimulation of guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide (Marshall et al., 1993; Abebe et al., 1995; Haynes et al., 1995; Ali et al., 1997). Whether cyclic GMP levels are elevated through a direct effect upon guanylate cyclase or through competition with cyclic AMP for a common phosphodiesterase (see Pelligrino & Wang, 1998) is at present unclear. Whatever the mechanism, it is clear that A2A adenosine receptor activation by NECA elevates cyclic GMP levels, indicating that protein kinase G may also play a role in the NECA-mediated inhibition of epididymal smooth muscle contractility. Although the A2A adenosine receptor antagonist, ZM 2421385, shifted cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP accumulation curves to the right it abolished the inhibitory response of the tissue to NECA. This data should be considered in light of the activity of phosphodiesterases in reducing elevations in cyclic nucleotide levels in contractility studies, but not in cyclic nucleotide accumulation studies where phosphodiesterase inhibitors are present. Thus it is possible that in contractility studies, in the presence of ZM 241385, NECA does not stimulate the accumulation of enough cyclic nucleotides to significantly activate protein kinases before phosphodiesterases act.

Further investigation showed that both the protein kinase A activator, Sp-8-Br-cAMPs and the protein kinase G activator, APT-cGMP inhibited smooth muscle contractility. Furthermore, the responses to these cyclic nucleotide analogues, Sp-8-Br-cAMPs and APT-cGMP, were inhibited by charybdotoxin and glibenclamide respectively, indicating the involvement of distinct K+ channels in protein kinase A- and protein kinase G-mediated responses. In contrast to the cyclic nucleotide analogue inhibition of contraction responses, responses to NECA appear smaller and more sensitive to the effects of both glibenclamide and charybdotoxin. The most likely explanation for these findings are that, in contrast to cyclic nucleotide analogue responses, the responses to NECA are mediated through increases in both cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP and are therefore more sensitive to the action of intracellular phosphodiesterases. That glibenclamide partially inhibited the APT-cGMP-mediated response indicates the involvement of KATP channels in the inhibition of epididymal contractility. This finding is not unusual, however, the possibility that protein kinase G, rather than protein kinase A is responsible for activating these channels is not consistent with most evidence of KATP function (see Standen & Quayle, 1998). Furthermore APT-cGMP caused as large an inhibition of phenylephrine-induced contractile responses as did Sp-8-Br-cAMPs, possibly indicating that either this analogue, or protein kinase G itself, may also act through mechanisms distinct from KATP channels to relax epididymal smooth muscle. There are many potential avenues for interaction between the cyclic AMP- and cyclic GMP-related systems in this tissue. These may include the cross-activation of protein kinase G by cyclic AMP, or the protein kinase A inhibition of phosphodiesterase (I) activity (see Lincoln et al., 1995; Quayle et al., 1997; Pelligrino & Wang, 1998). However, the simplest explanation of the data presented in this study is that NECA, through A2A adenosine receptors, stimulates increases in both cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP. These intracellular messengers respectively activate protein kinases A and G leading to the phosphorylation of both charybdotoxin and glibenclamide sensitive K+ channels. This hypothesis is consistent with distinct mechanisms of action of A2 adenosine receptors previously described Kleppisch & Nelson (1995) and Barrett-Jolley et al. (1996). It is also consistent with reports of A2 adenosine receptor-mediated vasodilation being KATP channel-dependent (Marshall et al., 1993; Dart & Standen, 1993; Sabates et al., 1997) and KATP channel-independent (Dunker et al., 1995; Haynes et al., 1995). That the responses to NECA were only partially reversed by glibenclamide and abolished by charybdotoxin is an unusual finding, particularly since an increased concentration of glibenclamide produced no further effect. One possible explanation for this finding may be that charybdotoxin-sensitive K+ channels may be more effective in inhibiting agonist-stimulated contractions (see Brayden, 1996). Alternatively, the relative production of cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP following the addition of NECA may be the limiting step in determining K+ channel activation and inhibition of contractility. It is also possible that the relative abundance of each of these channels may be the limiting factor in achieving any level of inhibition of contractility.

Acknowledgments

J.M. Haynes was a Ramsay fellow at Prince Henry's Institute of Medical Research and is currently a Faculty Fellow at RMIT University.

Abbreviations

- APT-cGMP

8-(-aminophenylthio) guanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- CGS 21680

2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenethylamino-N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamido-adenosine

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4]-oxadiazol [4,3-A] quinoxaline-1-one

- (S)-ENBA

(2S)-N6-[2-endo-norbornyl]adenosine

- Sp-8-Br-cAMPs

(Sp)-8-bromoadenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate

- ZM 241385

4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]-triazolo-[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol

References

- ABEBE W., HUSSAIN T., OLANREWAJU H., MUSTAFA S.J. Role of nitric oxide in adenosine receptor-mediated relaxation of porcine coronary artery. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;38:H1672–H1678. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.5.H1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AKATSUKA Y., EGASHIRA K. , KATSUDA Y., NARISHIGE T., UENO H., SHIMOKAWA H., TAKESHITA A. ATP sensitive potassium channels are involved in adenosine A2 receptor mediated coronary vasodilatation in the dog. Cardiovasc. Res. 1994;28:906–911. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALI S., METZGER W.J., OLANREWAJU H.A., MUSTAFA S.J. Adenosine receptor-mediated relaxation of rabbit airway smooth muscle: a role for nitric oxide. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:L581–L587. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.3.L581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRETT-JOLLEY R., COMTOIS A., DAVIES N.W., STANFIELD P.R., STANDEN N.B. Effect of adenosine and intracellular GTP on KATP channels of mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Memb. Biol. 1996;152:111–116. doi: 10.1007/s002329900090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAYDEN J.E. Potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1996;23:1069–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWNHILL V.R., HOURANI S.M.O., KITCHEN I. Differential distribution of A2 adenosine receptors in the epididymal and prostatic portions of the rat vas deferens. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;303:97–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG H.Y. The involvement of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in β2-adrenoceptor agonist-induced vasodilatation on rat diaphragmatic microcirculation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1024–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DART C., STANDEN N.B. Adenosine-activated potassium current in smooth muscle cells isolated from the pig coronary artery. J. Physiol. 1993;471:767–786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNCKER D.J., VAN ZON N.J., PAVEK T.J., HERRLINGER S.K., BACHE R.J. Endogenous adenosine mediates coronary vasodilation during exercise after K+ATP channel blockade. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:285–295. doi: 10.1172/JCI117653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., ABBRACCHIO M.P., BURNSTOCK G., DALY J.W., HARDEN T.K., JACOBSON K.A., LEFF P., WILLIAMS M. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUARDABASSO V., MUNSON P.J., RODBARD D. A versatile method for simultaneous analysis of families of curves. FASEB J. 1988;2:209–215. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.3.3350235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HADJKADDOUR K. , MICHEL A., LAURENT F., BOUCARD M. Smooth muscle relaxant activity of A1- and A2-selective adenosine receptor agonists in guinea pig trachea: involvement of potassium channels. Fund. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996;10:269–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1996.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYNES J., OBIAKO B., THOMPSON W.J., DOWNEY J. Adenosine-induced vasodilation: receptor characterization in pulmonary circulation. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:H1862–H1868. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.5.H1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYNES J.M., ALEXANDER S.P.H., HILL S.J. A1 and A2 adenosine receptor modulation of contractility in the cauda epididymis of the guinea-pig. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:570–576. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYNES J.M., HILL S.J. α-Adrenoceptor mediated responses of the cauda epididymis of the guinea-pig. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:1203–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRAMATSU T., KUME H., KOTLIKOFF M.I., TAKAGI K. Role of calcium-activated potassium channels in the relaxation of tracheal smooth muscles by forskolin. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1994;21:367–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1994.tb02529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG Y., KWOK K.H. Effects of putative K+ channel blockers on beta-adrenoceptor-mediated vasorelaxation of rat mesenteric artery. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1997;29:515–519. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEPPISCH T., NELSON M.T. Adenosine activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in arterial myocytes via A2 receptors and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. PNAS (U.S.A.) 1995;92:12441–12445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINCOLN T.M., KOMALAVILAS P., BOERTH N.J., MACMILLAN-CROW L.A., CORNWELL T.L. cGMP signaling through cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Adv. Pharmacol. 1995;34:305–322. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL J.M., THOMAS T., TURNER L. A link between adenosine, ATP-sensitive K+ channels, potassium and muscle vasodilatation in the rat in systemic hypoxia. J. Physiol. 1993;472:1–9. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORO M.A., RUSSELL R.J., CELLEK S., LIZASOAIN I., SU Y., DARLEY-USMAR V.M., RADOMSKI M.W., MONCADA S. cGMP mediates the vascular and platelet actions of nitric oxide: confirmation using an inhibitor of the soluble guanylyl cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (U.S.A.) 1996;93:1480–1485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKASHIMA M., VANHOUTTE P.M. Isoproterenol causes hyperpolarization through opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle of the canine saphenous vein. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;272:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLIGRINO D.A., WANG Q. Cyclic nucleotide crosstalk and the regulation of cerebral vasodilation. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998;56:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POUCHER S.M., KEDDIE J.R., SINGH P., STOGGALL S.M., CAULKETT P.W.R., JONES G., COLLIS M.G. The in-vitro pharmacology of ZM-241385, a potent, nonxanthine, A2a selective adenosine receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:1096–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRENTICE D.J., HOURANI S.M.O. Activation of multiple sites by adenosine analogues in the rat isolated aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1509–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUAYLE J.M., NELSON M.T., STANDEN N.B. ATP-sensitive and inwardly rectifying potassium channels in smooth muscle. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:1165–1232. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SABATES B.L., PIGOTT J.D., CHOE E.U., CRUZ M.P., LIPPTON H.L., HYMAN A.L., FLINT L.M., FERRARA J.J. Adrenomedullin mediates coronary vasodilation through adenosine receptors and KATP channels. J. Surgical Res. 1997;67:163–168. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.4985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHERIDAN B.C., MCINTYRE R.C., MELDRUM D.R., FULLERTON D.A. KATP channels contribute to β- and adenosine receptor-mediated pulmonary vasorelaxation. Am. J. Phys. 1997;273:950–956. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANDEN N.B., QUAYLE J.M. K+ channel modulation in arterial smooth muscle. Acta. Physiol. Scand. 1998;164:549–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER ZYPP, MAJEWSKI Effect of cGMP inhibitors on the actions of nitrodilators in rat aorta. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1998;25:38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WELLMAN G.C., QUAYLE J.M., STANDEN N.B. ATP-sensitive K+ channel activation by calcitonin gene-related peptide and protein kinase A in pig coronary arterial smooth muscle. J. Physiol. 1998;507:117–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.117bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]