Abstract

Honey bees are perhaps the most versatile models to study the cellular and pharmacological basis underlying behaviours ranging from learning and memory to sociobiology. For both aspects octopamine (OA) is known to play a vital role.

The neuronal octopamine receptor of the honey bee shares pharmacological similarities with the neuronal octopamine receptor of the locust. Both, agonists and antagonists known to have high affinities for the locust neuronal octopamine receptor have also high affinities for the bee neuronal octopamine receptor.

The distribution of receptors is more or less congruent between locusts and bees. Optic lobes and especially the mushroom bodies are areas of greatest octopamine receptor expression in both species, which mirrors the physiological significance of octopamine in the insect nervous system.

The neuronal octopamine receptor of insects served as a model to study the pharmacological similarity of homologous receptors from distantly related species, because bees and locusts are separated by at least 330 million years of evolution.

Keywords: Octopamine receptor, insect, insecticide, evolution, receptor pharmacology, locust, honey bee

Introduction

The biogenic monoamine octopamine (OA) gained substantial interest because it has widespread modulatory actions in invertebrates (Orchard, 1982; Evans, 1985; Bicker & Menzel, 1989; Roeder, 1994; 1999). OA is believed to play an important role for the general control of behaviour, regulating the motivational state of the animal (Hoyle, 1986; Sombati & Hoyle, 1984a,1984b; Bacon et al., 1995; Roeder et al., 1998). In insect, crustaceans and molluscs, numerous effects of OA on peripheral targets such as muscles and within the central nervous system are known. As peripheral targets are easily accessible to experimental manipulation, the number of studies dealing with OA's action on these tissues is far greater than those dealing with its role in the central nervous system. One of the most impressive examples of OA's action on the behavioural state of an invertebrate came from studies on lobsters. OA together with 5-HT regulates the social and aggressive state of the lobster in a well coordinated way. These two amines function as ‘gainsetters' leading to expression of specific sets of behaviours (Livingstone et al., 1980). The initiation and maintenance of rhythmic behaviours such as flying and walking in insects, swimming in crustaceans or chewing in molluscs was found to be dependent on OA (Sombati & Hoyle, 1984b; Mulloney et al., 1987; Kyriakides & McCrohan, 1989). Even complex behaviours like learning and memory are influenced in different ways by this compound (Dudai et al., 1987; Menzel et al., 1988; Hammer, 1993; Hammer & Menzel, 1998). Recently, another exciting action of OA became apparent. Robinson et al. (1999) found that bees, injected with OA receptor (OAR) agonists showed a significant increase in their ability to discriminate nestmates from non-nestmates. They showed an increased aggressiveness against non-nestmates and a reduced aggressiveness against nestmates. The effects caused by OAR agonist injection could be blocked by coinjection with OAR antagonists.

Beside this outstanding physiological significance in invertebrates, the receptors for OA attained additional interest because OA is, together with its biological precursor tyramine, the only non-peptide transmitter whose physiological role is restricted to invertebrates. Octopaminergic systems of invertebrates, and adrenergic systems of vertebrates share numerous physiological similarities, indicating that they are homologous (Roeder, 1994; 1999; Roeder & Nathanson, 1993). Nevertheless, the pharmacological profiles of OARs and adrenergic receptors are very different. Its restriction to invertebrates, together with the observation that some well known insecticides develop their insecticidal activity through interaction with OAR, focused invertebrate pharmacology on this target. These efforts resulted in the development of various high affinity and highly specific agonists. Surprisingly, OAR are the only invertebrate metabotropic receptors with a known, peculiar pharmacological profile that is not entirely based on vertebrate pharmacology. Among the four OAR subtypes that could be distinguished pharmacologically, the predominant neuronal OAR (class 3 receptor; Roeder, 1992) is believed to be the target for these insecticides.

To study the significance of octopaminergic neurotransmission, OAR from different invertebrates were cloned (von Nickisch-Roseneck et al., 1996; Han et al., 1998; Gerhardt et al., 1997a,1997b). In addition, OA-depleted Drosophila mutants were produced (Monastirioti et al., 1996). Both approaches gave relatively little additional information about the significance of octopaminergic neurotransmission. The main reason for this unsatisfactory situation is the unavailability of OAR knock-outs in these animals. As these knock-outs can not be expected in the next few years, alternatives are required.

The wealth of pharmacological information about OAR pharmacology is primarily obtained from locusts (Roeder, 1990; 1995) and cockroaches (Nathanson & Greengard, 1973; Nathanson, 1985). Numerous highly specific and high affinity agonists and antagonists are available, but it is not known if these pharmacological features are peculiar to locusts or cockroaches respectively, or if they are of more general importance, meaning that these compounds can also be used for other insects. Honey bees are ideally suited for this purpose because pharmacology could be combined with behaviour, opening the possibility to dissect octopaminergic neurotransmission in the insect brain with pharmacological tools (Kloppenburg & Erber, 1995; Mercer & Menzel, 1982; Mercer & Erber, 1983; Hammer & Menzel, 1998). With respect to two questions, the basis of learning and memory as well the basis of kin selection, both of outstanding interest for neurobiologists and behavioural pharmacologists, bees are the model of choice. Invertebrate models for learning and memory are attractive but became less important when significant advances were made in understanding the mechanism of hippocampal LTP. Among the invertebrate models, the honey bee is closest to the situation found in vertebrates with respect to the learning abilities. Very recently it became apparent that LTP is not necessarily coupled to learning and memory (Zamarillo et al., 1999). This should result in a renaissance of invertebrate models, especially the honey bee, because learning can be studied in great detail using this system. As mentioned above, OA has also an effect on the ability of bees to distinguish between nestmates and non-nestmates, an absolute requirement for social systems (Robinson et al., 1999). The wealth of agonists and antagonists identified in this study, that act specifically and with high affinity on the main neuronal octopamine receptor, the one that is believed to be responsible for most behavioural effects of OA, opens the opportunity to study these questions.

In addition, this study opens the possibility to evaluate the pharmacological relatedness between homologous receptors of distantly related species. Vertebrates are not well suited to study this interesting question, because the great variety of receptor-subtypes makes direct comparison between two homologous receptors from distantly related species almost impossible. The insect neuronal OAR is perhaps the best candidate to address this question, because its pharmacology has been studied in great detail, and the homologous receptors of different species could be characterized easily. It has to be borne in mind that the evolutionary lines of bees and locusts split about 330 million years ago, which is as long as mammals and birds are separated (Burmester et al., 1998). Prior to doing in vivo pharmacology with an insect such as the bee, the pharmacology of the OAR needs to be explored, especially with respect to the agonists and antagonists that should be used.

The current study addresses two main questions. (1) Are there high affinity agonists and antagonists for the neuronal OAR of the honey bee that could be used to specifically activate or block octopaminergic neurotransmission within the bees' CNS? (2) Are the pharmacological essentials of neuronal OAR studied in one insect species applicable to OAR's of other species or are these findings more or less species specific?

Methods

Animals

Experiments were done with adult honey bee workers (Apis mellifera), and with desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria) of both sexes, 2–20 days after imaginal moult. The locusts were reared at approximately 35°C (light–dark cycle 12–12 h), and fed with a diet of bran and grass. Adult honey bee workers were caught at the entrance of the hive.

Chemicals

[3H]-NC-5Z (4-azido, 2, 6-dimethyl phenyliminoimidazolidine; 40 Ci mmol−1), and St 92 (2, 4, 6-triethyl phenyliminoimidazolidine) were generous gifts from Dr J. A. Nathanson (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, U.S.A.; Nathanson, 1989). The other phenyliminoimidazolidines (NC 7: 4-chlor, 2-methyl; NC 5: 2, 6-diethyl) were from Shell Agriculture, and Boehringer Ingelheim, demethylchlordimeform, phentolamine and maroxepine were from Ciba-Geigy. The aminooxazoline AC6 (4-chlor, 2-methyl-aminooxazoline) was generously made available by Cyanamid, and the antagonist epinastine was a gift from Boehringer Ingelheim. Octopamine HCl, tyramine HCl, synephrine HCl, metoclopramide and mianserin were from Sigma, chlordimeform and chlorpromazine from Serva. All other chemicals were of the highest quality available.

Incubation

The nervous tissue (brain, suboesophageal ganglion, and thoracic ganglia) of adult honey bees or desert locusts was carefully dissected, and stored frozen in incubation buffer (Tris/acetic acid 50 mM, MgSO4 5 mM, pH 7.6, supplemented with 200 μM phenyl methyl sulphonyl fluoride (PMSF)) until use. The nervous tissue was homogenized, the homogenate centrifuged (20,000×g, 30 min, 2°C), and the pellets were resuspended in the original volume. This procedure was repeated twice to obtain a washed preparation. Pellets were stored frozen at −70°C until use. The incubation continued for 60 min at room temperature, and was terminated by filtration through pre-treated glass fibre filters (0.3 % polyethyleneimine). A total volume of 250 μl was used throughout the studies, with protein concentrations ranging from 0.5–1.5 mg ml−1. Each experiment was performed at least three times in triplicate. Further experimental details were given previously (Roeder & Nathanson, 1993; Wedemeyer et al., 1992). To study saturation parameters, [3H]-NC-5Z concentrations ranging from 0.1–2 nM were used. Nonspecific binding was determinded in the presence of 10 μM cold OA. Filtration was performed using a Skatron like system.

Receptor densities for the bee mushroom bodies, optic lobes and remainder of the brain were evaluated using saturation analysis followed by Scatchard analysis.

To study brain area specific expression of the octopamine receptor, the brains of locusts and bees were desheathed, the retinae, the optic lobes, the mushroom bodies, the antennal lobes, the remainder of the brain, the suboesophageal ganglion and the three thoracic ganglia were dissected, and used to determine the OAR density.

Evaluation

Results of the competition experiments were evaluated using the LIGAND program (Munson & Rodbard, 1980). Most of the data for the locust neuronal octopamine receptor were taken from Roeder (1995).

Results

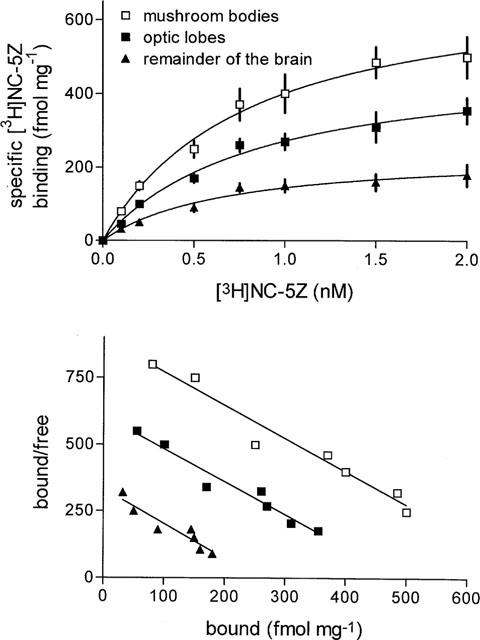

The tritiated, high-affinity OAR agonist [3H]-NC-5Z displays very high affinity for a single binding site in the honey bee nervous system. The site is saturated at nanomolar concentrations, and binding is fully reversible. The saturation experiments were performed with three different parts of the bee brain; the mushroom bodies, the optic lobes and the remainder of the brain. The binding sites in all three tissues could be saturated even at low radioligand concentrations (Figure 1, top). A closer evaluation of the saturation experiments was done using Scatchard-analysis (Figure 1, bottom). For all three brain areas studied, all points are more or less on the straight line indicating the presence of a single class of non-interacting binding sites (inclinations for optic lobes −0.84±0.14, the mushroom bodies −0.79±0.11 and for the remainder of the brain −0.68±0.15). For the optic lobes, the maximal number of binding sites is 500±36 fmol mg−1 protein, for the mushroom bodies 719±42 fmol mg−1 protein and for the remainder of the brain 243±12 fmol mg−1 protein. Hill-plot analysis of these data further gave evidence for the existence of single class of non-interacting binding site. The corresponding Hill-coefficients are all close to 1 (optic lobes Hcoeff=1.035±0.045 r2=0.99; mushroom bodies Hcoeff=0.995±0.037, r2=0.993; remainder of the brain Hcoeff=1.01±0.06, r2=0.992).

Figure 1.

Saturation analysis of [3H]-NC-5Z binding to honey bee nervous tissue membranes. Three different parts of the honey bee brain, the mushroom bodies, the optic lobes and the remainder of the brain (central brain without mushroom bodies and antennal lobes) were prepared. [3H]-NC-5Z concentrations ranging from 0.1–2 nmol were used. Each concentration was tested at least three to four times in triplicate. s.d. is given as vertical bars (top). A Scatchard-plot of the saturation data is shown in the lower part of the figure.

Pharmacology

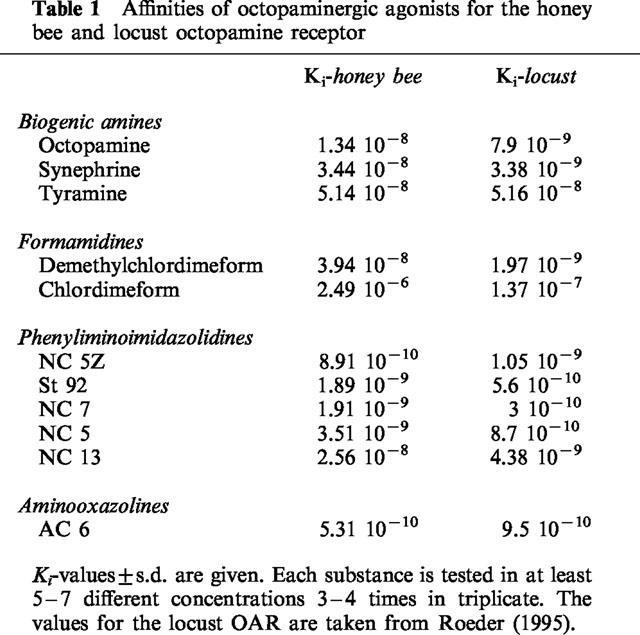

The pharmacological characterization of the bee neuronal OAR was performed with numerous octopaminergic agonists and antagonists, known from other invertebrates. Biogenic amines with structural similarities to the natural ligand OA displayed affinities very similar to those known from other neuronal OAR. In this group of substances, OA itself has highest affinity (13.4 nM) for its own receptor followed by its N-methylated product synephrine (34.4 nM). The precursor of OA, tyramine, has lowest affinity in this group (51.4 nM). If the Ki-values are compared with the corresponding values obtained from the locust neuronal OAR, it is obvious that the affinities of the three compounds are almost in the same range. The rank order of affinities is somewhat different in the bee if compared with the locust neuronal OAR, where synephrine has a 2 fold higher affinity than OA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Affinities of octopaminergic agonists for the honey bee and locust octopamine receptor

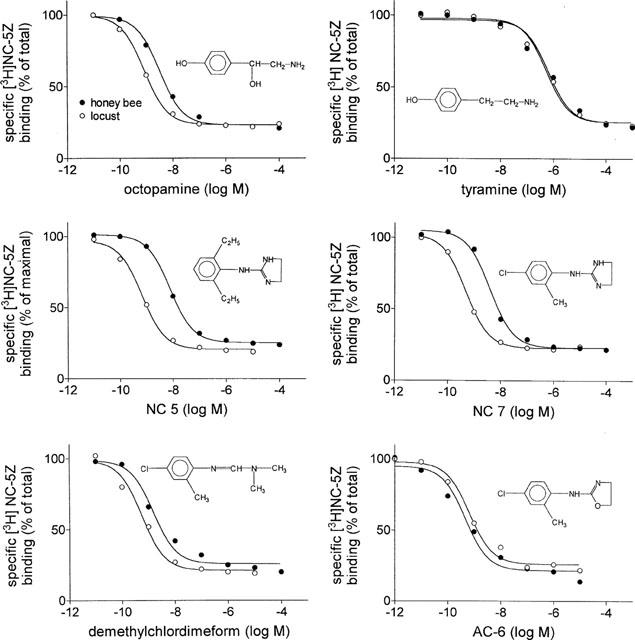

Regarding this high degree of similarity, other high affinity agonists, derived from different classes of compounds, were tested. Although they have different chemical structures, it ruled out that compounds known to have high affinities for locust neuronal OAR also have high affinities for the bee neuronal OAR. Among them are members of the formamidines (demethylchlordimeform, chlordimeform), the phenyliminoimidazolidines (NC 5, NC 7, NC 5Z, NC 13, St 92), and the aminooxazolines (AC 6). The overall affinities are in the lower nanomolar or even in the subnanomolar range, a characteristic of high affinity agonists (Figure 2, Table 1). Although the affinities are similar in bees and locusts, the rank orders of affinities show minor differences. The agonist with highest affinity for the locust neuronal OAR, NC 7, has an about five times lower affinity in the honey bee. Three other agonists, St 92 (1.89 nM), NC 5Z (0.89 nM), and AC 6 (0.53 nM) have higher affinities in the bee compared with the locust. AC 6, the substance with highest affinity in the bee, has an about five times higher affinity than in the locust. The radioligand used in this study, NC 5Z, is among the compounds with an affinity in the subnanomolar range. NC 13 and St 92 are two compounds that were used to distinguish between central and peripheral receptors (Nathanson, 1993). Whereas St 92 has higher affinity for neuronal OAR than NC 13, the rank-order is reversed for peripheral type OAR. A pharmacological characteristic shared by most OAR is the high affinity of the formamidines demethylchlordimeform and chlordimeform. Demethylchlordimeform (Ki=3.94 nM) has an affinity that is about 500 times higher compared with chlordimeform (2.49 μM), which is also known for most OAR.

Figure 2.

Affinity of selected high affinity agonists for the honey bee and locust neuronal octopamine receptor. Increasing concentrations of six different high affinity agonists were used to displace specific [3H]-NC-5Z binding in the bee and locust nervous system. Each concentration is tested at least three times in triplicate.

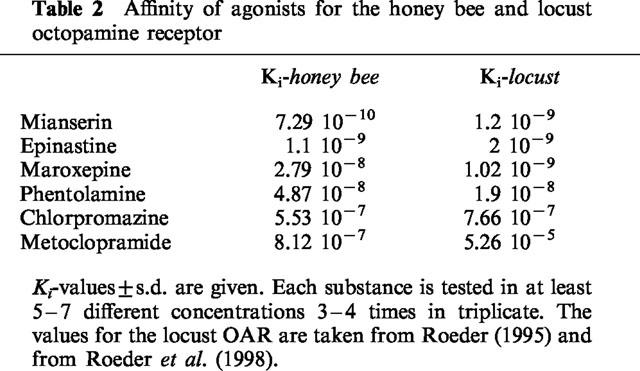

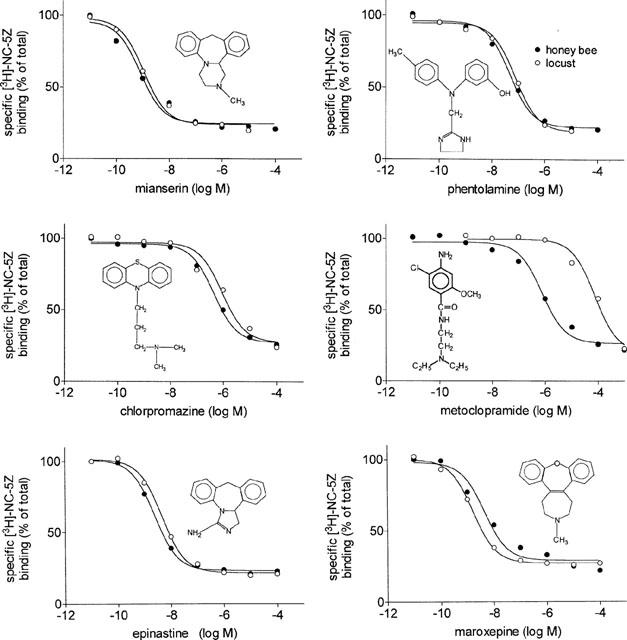

The classification of OAR into the different sub-populations was performed with antagonists. It its possible to classify the four OAR of the locust simply by determination of the affinities of four different antagonists. These antagonists are mianserin, phentolamine, chlorpromazine and metoclopramide. The neuronal OAR of the honey bee is characterized by the following rank order of affinities: mianserin (0.73 nM)>phentolamine (49 nM)>chlorpromazine (550 nM)>metoclopramide (810 nM, Table 2) which is the same order found for the locust neuronal OAR (Figure 3). The antagonist with highest affinity is mianserin, as for the locust neuronal OAR. Its Ki value is below 1 nM (0.73 nM) which is exceptionally high. Although the rank order of affinities of these four antagonists is the same as found in the locust CNS, metoclopramide has an affinity much closer to that of chlorpromazine than in the locust CNS (Figure 3). In addition to these four antagonists, two others are of outstanding interest. These are epinastine and maroxepine, both of them were shown to have exceptionally high affinities for the locust neuronal OAR. Maroxepine has high affinity for the bee OAR, but its affinity is about 20 times lower than in the locust CNS. Epinastine is of even greater importance, it shows very high affinity properties in both preparations with affinities between 1 and 2 nM (Table 2, Figure 3). In contrast to most other known high-affinity antagonists, epinastine has relatively low affinities for other receptors for biogenic amines (Roeder et al., 1998), which makes this compound ideally suited to block octopaminergic neurotransmission without disturbing other systems.

Table 2.

Affinity of agonists for the honey bee and locust octopamine receptor

Figure 3.

High affinity antagonists of the honey bee and locust octopamine receptor. The effect of increasing concentrations of six different antagonists on the displacement of specific [3H]-NC-5Z binding is plotted for the honey bee and locust neuronal octopamine receptor. Details see Figure 2.

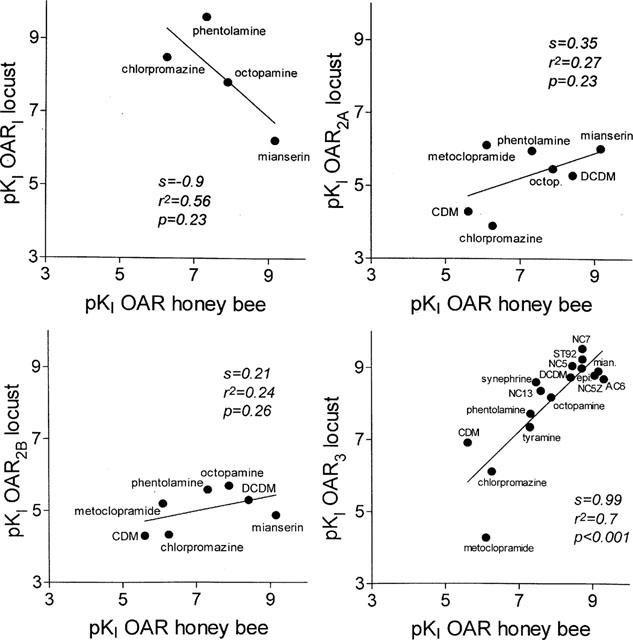

Comparison of the affinities of the compounds tested with the corresponding affinities obtained for all four OAR classes (OAR1/2A/2B from Evans, 1981; 1985; OAR3 from Roeder, 1990; 1995; Roeder et al., 1998) of the locust showed different degrees of congruency. With the type I OAR, the correlation is lowest (s=−0.9, r2=0.56, P=0.23). Both, with the type 2A (s=0.35, r2=0.27, P=0.23), and 2B (s=0.21, r2=0.24, P=0.26) moderate congruencies could be observed. The highest homology could be observed with the neuronal type 3 OAR (s=0.99, r2=0.7, P<0.001). As seen in Figure 4 most points, each representing a specific compound, are more or less on the bisector of the angle indicating their high degree of homology.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the pharmacological profile of the bees neuronal octopamine receptor with those of all four octopamine receptors of the locust. The affinities (pKi-values) of the substances tested on the honey bee neuronal OAR were compared with the corresponding values for the four different octopamine receptors of the locust. Each point represents a specific substance as indicated in the plot. Regression analysis of these points revealed different slopes (s), correlation coefficients (r2), and probabilities (P). CDM=chlordimeform, DCDM=demethylchlordimeform, epi.=epinastine, mian.=mianserin, octop.=octopamine.

Distribution of octopamine receptors within the insect nervous system

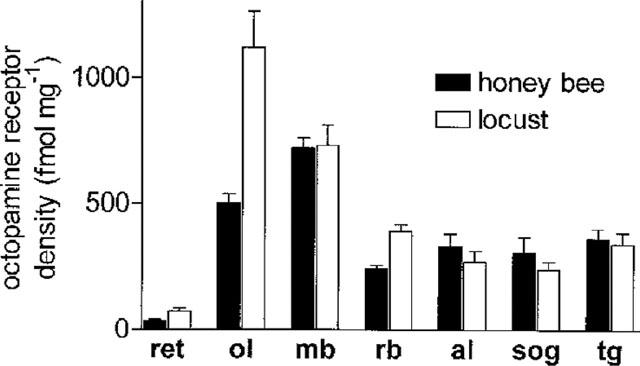

To study the OAR distribution in different parts of the honey bee and locust central nervous system, areas of the respective brains were isolated and used to measure the receptor density. In the honey bee, the receptor densities of the optic lobes, the mushroom bodies, and the remainder of the brain were evaluated using Scatchard analysis of saturation data. The other data were obtained from experiments using a single radioligand concentration and normalization with the above mentioned saturation data for the three brain areas. The highest density of the OAR binding site could be observed in the mushroom bodies of the bee. It is about 3 fold higher compared with the remainder of the brain. In addition to the concentration found in the mushroom bodies, the OAR concentration found in the optic lobes of the honey bee is also higher than that found in the remainder of the brain. In the other parts of the brain, the midbrain (supraoesophageal ganglion minus optic lobes), the antennal lobes, and in the suboesophageal ganglion and the thoracic ganglion the OAR, concentration is almost constant. The higher concentrations found in the mushroom bodies, and the optic lobes are significant (compared with the remainder of the brain). In opposite to the other parts studied, the retina is almost devoid of octopamine receptors.

In the nervous system of the locust, the distribution of OAR is slightly different. The parts of the nervous system that have only low basal concentrations of OAR are almost identical in locusts and bees. These are the remainder of the brain, the suboesophageal ganglion, the thoracic ganglia, and the antennal lobes. As in the bee, the retinae are devoid of octopamine receptors. Two parts of the brain display highest receptor concentration. These are the mushroom bodies and the optic lobes. In contrast to the situation found in the bee, the optic lobes of locusts are the parts of the brain with highest OAR concentration followed by the mushroom bodies.

Discussion

Receptor distribution

The biogenic monoamine OA is the best characterized modulatory compound in the insect nervous system. It is believed to modulate almost every peripheral organ, and most sense organs. In addition, it has numerous effects in the CNS. As mentioned earlier, habituation of visually induced startle response, and participation in the molecular processes underlying learning and memory are among these effects (Roeder, 1999). This functional role is reflected by the high receptor concentration in the corresponding brain areas, the optic lobes and the mushroom bodies respectively. Both brain areas are supplied with OA via identified OA containing neurones (Konings et al., 1988; Stevenson et al., 1992; Kreissl et al., 1994). The mushroom bodies of bees are innervated by identified ventral unpaired median neuron, the VUMmx1 neuron, with its soma located in the suboesophageal ganglion. Its important role in the memory formation was studied with a combination of electrophysiological and behavioural methods (Hammer, 1993). In the locust, a pair of identified, octopamine-containing neuron supplies large areas of the optic lobes with OA. Their somata are located in the ipsilateral deutocerebrum. These neuron are known to mediate dishabituation in the visual system (Bacon et al., 1995; Roeder et al., 1998). In addition, a very large number of putative amacrines of the medulla (the second visual neuropile) contain OA. This congruency of receptor localization, OA immunoreactivity and physiological function points to the importance of the corresponding brain areas for octopaminergic neurotransmission (Erber et al., 1993; Erber & Kloppenburg, 1995).

Han et al. (1998) recently reported the expression of an OAR in the mushroom bodies of the fruitfly Drosophila. Expression in other parts of the brain could be neglected. Our observation gave a more differentiated picture. Although the mushroom bodies are areas of highest receptor density in bees and locusts, the receptors are present in other parts of the brain in considerable concentrations. This mirrors the physiological relevance of OA in e.g. the thoracic ganglia or the optic lobes.

We were not able to find pharmacological differences between mushroom body and e.g. optic lobe OAR, which indicates that the corresponding receptors are identical. The comparison of the receptor concentrations in the nervous systems of the locust and the honey bee revealed striking similarities. Although these insects are separated by about 330 billion years of evolution (Burmester et al., 1998), a time scale equivalent to the mammal-bird divergence, this feature has remained almost unchanged. Only the exceptional high concentration in the bees mushroom bodies might be an adaptation to the specific abilities in olfactory memory. This indicates that their last common ancestor had comparable octopaminergic systems. It is not possible to state if this pharmacological relatedness between holo- and hemimetabolous insects is only found for the octopaminergic system, because no comparable studies focussing on other transmitter systems e.g. serotonin or dopamine receptors, are available.

Pharmacological relatedness between locust and bee octopamine receptor

The pharmacological characterization of the bee neuronal OA receptor gives some very interesting information about the pharmacology of biogenic amine receptors in invertebrates. One of the most striking features is the relatively high degree of pharmacological homology between the locust and the bee neuronal OAR. The corresponding receptor of the locust was until now the only well characterized neuronal OAR. Therefore, it was not obvious if the pharmacological features of this receptor are peculiar to locusts or are applicable to insects in general. Bees and locusts belong to the two large different groups of modern insects, the holo- and hemimetabolic insects respectively. In the present paper, it is the first time that two such homologous receptors are compared for their specific pharmacological features. Surprisingly, the pharmacological profiles of OAR's remain almost constant in both species investigated. Only small changes were observed. Although holo- and hemimetabolous insects appear to be very similar in our eyes, they are separated by at least 330 million years of divergent evolution, equivalent to the mammal-bird split. Characteristically every compound that displays high affinity for the receptor in the bee also has high affinity for the receptor in the locust. The homology holds also true for those antagonists that were originally used to classify locust OAR's. The rank order of affinities of the four antagonists examined remained constant either in bees or locusts, clearly demonstrating the identity of the bee OAR as a class 3 OAR, which is further supported by the comparison of the corresponding pKi-values (Figure 4). This pharmacological relatedness implies that high affinity agonists and antagonists identified for one insect species should have similar characteristics in other insect species. In addition, it has to be borne in mind, that it should be very difficult to produce species specific or group specific receptor ligands that distinguish between different species. Potential insecticides should, therefore, be characterized by high affinity for the corresponding receptors of almost every insect species, either being a pest or an insect with economical importance (e.g. honey bee or silk moth). Differences in the insecticidal activity of known insecticides might be attributed to different affinities at the receptor site rather than to other reasons such as penetration of the body wall, or to behavioural (specialized food uptake) or ecological cues.

Taken together, our results indicate that OAR3 from distantly related species have very similar pharmacological features. High affinity compounds define these features independent of the species studied. This opens the opportunity specifically to activate or block octopaminergic neurotransmission in the insect CNS using agonists such as the phenyliminoimidazolidines NC 5 and NC 7 or the aminooxazoline AC 6, and antagonists such as epinastine or maroxepine. One point of general interest is the high degree of pharmacological relatedness between homologous receptors of distantly related species. In addition, comparison of the receptor distribution gives information about the physiological significance of the corresponding receptor systems. Similarities observed in the expression pattern might point to the fact that these receptors have a comparable physiological significance in the common ancestor of both species studied.

Figure 5.

Concentration of octopamine receptors in different parts of the nervous systems of the honey bee and the locust. The octopamine receptor concentration in the retinae (ret), the optic lobes (ol), the mushroom bodies (mb), the antennal lobes (al), the remainder of the brain (rb), the suboesophageal ganglion (sog), and the thoracic ganglia (tg) of the honey bee (white) and the locust (black) was evaluated and plotted as per cent of maximal binding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank J.A. Nathanson for [3H]-NC-5Z, Shell Agriculture, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ciba-Geigy and Cyanamid for compounds, and an anonymous referee for carefully reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the DFG (Ro 1241/2-3) and the GTZ (Gesellschaft für technische Zusammenarbeit, project: Integrated control of locusts). This work is based, in part, on a doctoral study of J. Degan at the University Hamburg.

Abbreviations

- OA

octopamine

- OAR

octopamine receptor

- PMSF

phenyl methyl sulphonyl fluoride

References

- BACON J.P., THOMPSON K.S.J., STERN M. Identified octopaminergic neurons provide an arousal mechanism in the locust brain. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;74:2739–2743. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BICKER G., MENZEL R. Chemical codes for the control of behaviour in arthropods. Nature. 1989;337:33–39. doi: 10.1038/337033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURMESTER T., MASSEY H.C., ZAKHARKIN S.O., BENES H. The evolution of hexamerins and the phylogeny of insects. J. Mol. Evol. 1998;47:93–108. doi: 10.1007/pl00006366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUDAI Y., BUXBAUM J., CORFAS G., OFARIM M. Formamidines interact with Drosophila octopamine recpetors, alter the flies' behaviour and reduce their learning ability. J. Comp. Physiol. 1987;161A:739–746. [Google Scholar]

- ERBER J., KLOPPENBURG P. The modulatory effects of serotonin and octopamine in the visual system of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). I. Behavioral analysis of the motion-sensitive antennal reflex. J. Comp. Physiol. 1995;176:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- ERBER J., KLOPPENBURG P., SCHEIDLER A. Neuromodulation by serotonin and octopamine in the honeybee: behaviour, neuroanantomy and electrophysiology. Experientia. 1993;49:1073–1083. [Google Scholar]

- EVANS P.D. Multiple receptor types for octopamine in the locust. J. Physiol. 1981;318:99–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS P.D.Octopamine Comprehensive Insect Physiol 1985Pergamon Press: Oxford; 499–529.In: Kerkut, G.A. & Gilbert, L. (eds)11 [Google Scholar]

- GERHARDT C., BAKKER R.A., PIEK G.J., PLANTA R.J., VREUGDENHIL E., LEYSEN J.E., VAN HEERIKHUIZEN H. Molecular cloning and pharmacological characterization of a molluscan octopamine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997a;51:293–300. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERHARDT C., LODDER H.C., VINCENT M., BAKKER R.A., PLANTA R.J., VREUGDENHIL E., KITS K.S., VAN HEERIKHUIZEN H. Cloning and expression of a complementary DNA encoding a molluscan octopamine receptor that couples to chloride channels in HEK 293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997b;272:6201–6207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMMER M. An unidentified neuron mediates the unconditioned stimulus in associative olfactory learning in honeybees. Nature. 1993;366:59–63. doi: 10.1038/366059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMMER M., MENZEL R. Multiple sites of associative odor learning as revealed by local brain microinjections of octopamine in honeybees. Learning Memory. 1998;5:146–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN K.-A., MILLAR N.S., DAVIS R.L. A novel octopamine receptor with preferential expression in Drosophila mushroom bodies. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:3650–3658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOYLE G.Generation of behaviour: the orchestration hypothesis Feedback and motor control in invertebrates and vertebrates 198657–75.In: Barnes, W.J.P. & Gladden Croom Helm, M.H. (eds.)

- KLOPPENBURG P., ERBER J. The modulatory effects of serotonin and octopamine in the visual system of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). II. Electrophysiological analysis of motion-sensitive neurons in the lobula. J. Comp. Physiol. 1995;176A:119–129. [Google Scholar]

- KONINGS P.N.M., VULLINGS H.G.B., GEFFARD M., BUIJS R.M., DIEDEREN J.H.B., JANSEN W.F. Immunocytochemical demonstration of octopamine-immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of Locusta migratoria and Schistocerca gregaria. Cell Tiss. Res. 1988;251:371–379. doi: 10.1007/BF00215846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREISSL S., EICHMÜLLER S., BICKER G., RAPUS J., ECKERT M. Octopamine-like immunoreactivity in the brain and suboesophageal ganglion of the honeybee. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;348:583–595. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KYRIAKIDES M.A., MCCROHAN C.R. Effect of putative rhythmic buccal motor output in Lymnea stagnalis. J. Neurobiol. 1989;20:635–650. doi: 10.1002/neu.480200704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIVINGSTONE M.S., HARRIS-WARRICK R.M., KRAVITZ E.A. Serotonin and octopamine produce opposite postures in lobsters. Science. 1980;208:76–79. doi: 10.1126/science.208.4439.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENZEL R., MICHELSEN B., RÜFFER P., SUGAWA M.Neuropharmacology of learning and memory in honey bees NATO ASI series H19, Modulation of synaptic plasticity in nervous systems 1988Springer Verlag: Berlin-Heidelberg; 332–350.In: Hertting, G. & Spatz, H.-C. (eds) [Google Scholar]

- MERCER A.R., ERBER J. The effects of amines on evoked potentials recorded in the mushroom bodies of the bee brain. J. Comp. Physiol. 1983;151A:469–476. [Google Scholar]

- MERCER A.R., MENZEL R. The effects of biogenic amines on conditioned and unconditioned responses to olfactory stimuli in the honeybee Apis mellifera. J. Comp. Physiol. 1982;145A:363–368. [Google Scholar]

- MONASTIRIOTI M., LINN J.C.E., WHITE K. Characterization of Drosophila ß-hydroxyxlase gene and isolation of mutant flies lacking octopamine. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3900–3911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03900.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLONEY B., ACEVEDO L.D., BRADBURY A.G. Modulation of crayfish swimmeret rhythm by octopamine and the neuropeptide proctolin. J. Neurophysiol. 1987;58:584–597. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.58.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUNSON P.J., RODBARD D. LIGAND: a versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding systems. Anal. Biochem. 1980;107:220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHANSON J.A. Characterization of octopamine-sensitive adenylate cyclase: Elucidation of a class of potent and selective octopamine-2 receptor agonists with toxic effects in insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:599–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHANSON J.A. Development of a photoaffinity ligand for octopamine receptors. Molec. Pharmacol. 1989;35:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHANSON J.A. Identification of octopaminergic agonists with selectivity for octopamine receptor subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;265:509–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHANSON J.A., GREENGARD P. Octopamine-sensitive adenylate cyclase: Evidence for a biological role of octopamine in nervous tissue. Science. 1973;180:308–310. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4083.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICKISCH-ROSENEGK E VON., KRIEGER J., KUBICK S., LAAGE R., STROBEL J., STROTMANN J., BREER H. Cloning of biogenic amine receptors from moths (Bombyx mori and Heliothis virescens) Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol. 1996;26:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(96)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORCHARD I. Octopamine, neurotransmitter, neurohormone and neuromodulator. Can. J. Zool. 1982;60:659–669. [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON G. , HEUSER L.M., LECONTE Y., LENQUETTE F., HOLLINGWORTH R.M. Neurochemicals aid bee nestmate recognition. Nature. 1999;399:534–535. [Google Scholar]

- ROEDER T. High-affinity antagonists of the locust neuronal octopamine receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;191:221–224. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94151-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROEDER T. A new octopamine receptor class in locust nervous tissue, the octopamine 3 (OA3) receptor. Life Sci. 1992;50:21–28. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90193-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROEDER T. Biogenic amines and their receptors in insects. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1994;107:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- ROEDER T. Pharmacology of the octopamine receptor from locust central nervous tissue (OAR3) Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROEDER T. Octopamine in invertebrates. Progr. Neurobiol. 1999;59:533–561. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROEDER T., NATHANSON J.A. Characterization of insect neuronal octopamine receptors. Neurochem. Res. 1993;18:921–925. doi: 10.1007/BF00998278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROEDER T., DEGEN J., GEWECKE M. Epinastine, a highly specific antagonist of the insect neuronal octopamine receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;349:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMBATI S., HOYLE G. Central nervous sensitization and dishabituation of reflex action in an insect by the neuromodulator octopamine. J. Neurobiol. 1984a;15:455–480. doi: 10.1002/neu.480150606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMBATI S., HOYLE G. Generation of specific behaviours in a locust by local release into neuropil of the natural neuromodulator ocotpamine. J. Neurobiol. 1984b;15:481–506. doi: 10.1002/neu.480150607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEVENSON P., PFLÜGER H.J., ECKERT M., RAPUS J. Octopamine immunoreactive cell populations in the locust thoracic-abdominal nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;315:382–397. doi: 10.1002/cne.903150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEDEMEYER S., ROEDER T., GEWECKE M. Pharmacological characterization of a 5-HT receptor in locust nervous tissue. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;223:173–178. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)94836-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAMARILLO D., SPRENGEL R., HVALBY O., JENSEN V., BURNASHEV N., ROZOV A., KAISER K.M.M., KÖSTER H.J., BORCHARDT T., WORLEY P., LÜBKE J., FROTSCHER M., KELLY P.H., SOMMER B., ANDERSEN P., SEEBURG P.H., SAKMANN B. Importance of AMPA receptors for hippocampal synaptic plasticity but not for spatial learning. Science. 1999;284:1805–1811. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]