Abstract

Pancreatic oedema occurs early in the development of acute pancreatitis, and the overall extent of fluid loss correlates with disease severity. The tachykinin substance P (SP) is released from sensory nerves, binds to the neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1-R) on endothelial cells and induces plasma extravasation, oedema, and neutrophil infiltration, a process termed neurogenic inflammation. We sought to determine the importance of neurogenic mechanisms in acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatic plasma extravasation was measured using the intravascular tracers Evans blue and Monastral blue after administration of specific NK1-R agonists/antagonists in rats and NK1-R(+/+)/(−/−) mice. The effects of NK1-R genetic deletion/antagonism on pancreatic plasma extravasation, amylase, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and histology in cerulein-induced pancreatitis were characterized.

In rats, both SP and the NK1-R selective agonist [Sar9 Met(O2)11]SP stimulated pancreatic plasma extravasation, and this response was blocked by the NK1-R antagonist CP 96,345. Selective agonists of the NK-2 or NK-3 receptors had no effect.

In rats, cerulein stimulated pancreatic plasma extravasation and serum amylase. These responses were blocked by the NK1-R antagonist CP 96,345.

In wildtype mice, SP induced plasma extravasation while SP had no effect in NK1-R knockout mice.

In NK1-R knockout mice, the effects of cerulein on pancreatic plasma extravasation and hyperamylasemia were reduced by 60%, and pancreatic MPO by 75%, as compared to wildtype animals.

Neurogenic mechanisms of inflammation are important in the development of inflammatory oedema in acute interstitial pancreatitis.

Keywords: Neurogenic inflammation, tachykinin, cerulein, sensory nerves

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is characterized by massive oedema of the pancreas and surrounding retroperitoneal tissues with concomitant profound losses of plasma proteins and intravascular volume. The 10% mortality in acute pancreatitis has been correlated with the volume of fluid loss into the peritoneal cavity as ascites (Maringhini et al., 1996). Infusion of the cholecystokinin (CCK) analogue cerulein rapidly induces plasma extravasation from the intravascular space to the pancreatic interstitium and peritoneal cavity in experimental animals (Klar et al., 1994). Inflammatory pancreatic oedema is one of the early characteristics of this model of acute pancreatitis and these fluid shifts are responsible for the development of systemic hypotension (Griesbacher et al., 1993). Thus, plasma extravasation resulting in pancreatic oedema is an early event of great clinical significance in the development of acute pancreatitis.

The initial phases of inflammation in skin, joint and airway that are induced by certain noxious stimuli are characterized by release of pro-inflammatory peptides from sensory neurons. Binding of these neuropeptides to endothelial cells results in plasma extravasation, neutrophil infiltration and vasodilatation, a process termed neurogenic inflammation. Neurogenic inflammation has been well studied in the trachea where inhaled noxious stimuli stimulate a subpopulation of sensory nerves to induce inflammation (McDonald, 1994). The sensory neurons responsible are capsaicin-sensitive unmyelinated C fibres that release the tachykinin substance P (SP) both centrally and peripherally following excitation (Otsuka & Yoshioka, 1993). SP binds to the G protein-coupled neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1-R) on endothelial cells and induces the formation of gaps between adjacent endothelial cells in post-capillary venules (Bowden et al., 1994). Albumin and fluid extravasate through these gaps into the interstitium resulting in inflammatory oedema.

In the pancreas, sensory neurons that contain immunoreactivity for SP have been found in the perivascular space of small arterioles, within connective tissue septae separating lobules, and adjacent to intrinsic neurons in the rat (De Giorgio et al., 1993). The function of SP in the pancreas has not been fully understood. We have shown that SP modulates pancreatic exocrine secretion (Kirkwood et al., 1999). In view of its known effects on the endothelium in tissue inflammation (Bowden et al., 1994), we hypothesized that SP might also serve as a pro-inflammatory peptide in acute pancreatitis by inducing plasma extravasation. We have shown that intravenous injection of either SP or capsaicin, which excites sensory nerves, stimulates extravasation of the albumin-bound dye Evans blue (EB) in mouse pancreas and this response is abolished by antagonism of the NK1-R (Figini et al., 1997). This observation suggests that SP and the NK1-R could mediate neurogenic inflammation in the pancreas. Elevated pancreatic SP levels are found in cerulein-induced pancreatitis in mice (Bhatia et al., 1998), and genetic deletion of the NK1-R reduces serum amylase and acinar cell necrosis in this model. Although these findings underscore the potential importance of SP in pancreatic inflammation, the mechanism of these effects remains unclear. Specifically, the effect of increased SP, as seen in cerulein-induced pancreatitis, on pancreatic microvascular permeability has not been studied. It is also unknown if SP-induced activation of the NK1-R is an important pro-inflammatory step in acute pancreatitis in other species, such as the rat.

We tested the hypothesis that tachykinins mediate inflammatory oedema, hyperamylasemia and the histologic changes characteristic of cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats and mice. Rats were chosen since there is an extensive body of literature available on both pancreatic pathophysiology and neurogenic inflammation in this species. Mice were also used due to the availability of animals with genetic deletion of the NK1-R. Our aims were to (1) determine whether SP induces plasma extravasation in the pancreas by activation of the NK1-R in both rats and mice, (2) use NK1-R antagonists to determine whether cerulein-induced plasma extravasation occurs by the NK1-R, and (3) use mice in which the NK1-R has been deleted by homologous recombination (NK1-R −/−) to examine the role of the NK1-R in cerulein-induced pancreatic plasma extravasation and inflammation.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were from Charles River (Hollister, CA, U.S.A.). NK1-R(+/+) mice were 129 Sv mice crossed a single time with C57BL/6. NK1-R(−/−) mice were generated by homologous recombination and gene targeting from 129 Sv mice and stem cells were implanted in C57BL/6 mouse blastocysts (Bozic et al., 1996), and were used at 25–30 g. All procedures complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animals Resources, National Academy of Sciences, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.) and were approved by the UCSF Committee on Animal Research.

Materials

The NK1-R selective agonist [Sar9 Met(O2)11]SP was from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Mountain View, CA, U.S.A.). SP, the NK2-R selective agonist [βAla8]NKA, the NK3-R selective agonist [MePhe7]NKB and bradykinin were from Peninsula Labs Inc. (Belmont, CA, U.S.A.). The NK1-R antagonist RP 67,580 was from Rhone Poulenc Rorer (Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.). The NK1-R antagonist CP 96,345 was from Pfizer, Inc. courtesy of Dr Saul B. Kadin (Groton, CT, U.S.A.). The NK1-R antagonist SR 140,333 was from Sanofi Recherche courtesy of Dr Xavier Emonds-Alt (Montpellier, France). The B2-R antagonist HOE 140 was from Hoechst courtesy of Dr K. Wirth (Frankfurt, Germany). Tachykinins and HOE 140 were dissolved in 0.9% NaCl, while neurokinin receptor antagonists were dissolved in DMSO (Fluka Chem. Corp., Milwaukee, WI, U.S.A.) and then re-constituted in 0.9% NaCl to achieve a final concentration of ⩽5% DMSO. This concentration of DMSO alone had no effect on plasma extravasation (data not shown). Monastral blue was a generous gift from Donald McDonald (UCSF). Cerulein, EB, formamide and paraformaldehyde were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Heparin sulphate (porcine) was from SoloPak Labs, Inc. (Elk Grove Village, IL, U.S.A.). Ketamine hydrochloride was from Parke-Davis (Morris Plains, NJ, U.S.A.). Xylazine hydrochloride was from The Butler Co. (Columbus, OH, U.S.A.). Hexadecylmethylamonium bromide (HTAB) and tetramethylbenzidine substrate (TMB) were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Experimental design

Experiments in rats

Neurogenic inflammation was studied in rats by two different methods, (a) the bolus intravenous administration of SP, and (b) the induction of acute mild interstitial pancreatitis by continuous infusion of cerulein. Endpoints studied include EB extravasation, serum amylase, and monastral blue extravasation, as described in Methods below. During the short time course of these experiments (2 h) there are no significant changes in pancreatic histology or myeloperoxidase activity.

Experiments in mice

Neurogenic inflammation was studied in both NK1-R (+/+) and (−/−) mice by two different methods, (a) the bolus intravenous administration of SP, and (b) the induction of acute mild interstitial pancreatitis by 12 h injections of cerulein. Endpoints studies include EB extravasation, serum amylase, pancreatic and lung myeloperoxidase, and histology, as described in Methods below.

EB extravasation

After intravenous injection, EB binds to albumin and thus remains in the vasculature. If gaps form in the endothelial barrier of sufficient size to permit the extravasation of albumin, EB leaks into the interstitium and can be quantitated in tissues (Saria & Lundberg, 1983). EB accumulation was measured as previously described (Figini et al., 1997). In brief, EB (30 mg kg−1 of a 3% solution suspended in 0.9% NaCl) was injected into the femoral vein of anaesthetized animals. Animals were transcardially perfused with 50 ml of phosphate-buffered saline containing 100 units ml−1 heparin sodium, followed by 200 ml of 1% paraformaldehyde in 50 mM citrate buffer, pH 3.5. EB was extracted following 48 h of incubation in formamide and quantified by measuring the optical density of the extract at 620 nm. Plasma analysis by gel filtration chromatography showed that >90% of EB was in the bound, rather than free form. Thus EB is not subject to passive diffusion across the endothelium. Results are expressed as ng EB per mg dry tissue weight to minimize artifact due to tissue oedema. In some experiments, selective neurokinin receptor agonists ([Sar9 Met(O2)11]SP, [βAla8]NKA, and [MePhe7]NKB) at a dose of 4–10 nmol kg−1 were injected into the femoral vein immediately after EB. Bradykinin (4 nmol kg−1) was injected into NK1-R(−/−) mice to verify that the EB indicator system was still functional. Two different NK1-R antagonists (CP 96345 and RP 67580, both 1 μmol kg h−1 i.v.) were used in rats to confirm the dependence of cerulein-induced changes on activation of the NK1-R (Garret et al., 1991). In mice, the NK1-R antagonist SR 140333 (1 mg kg−1) was used to demonstrate that SP-induced plasma extravasation in NK1-R(+/+) occurred via the NK1-R (Emonds-Alt et al., 1993). The NK1-R antagonists were selected based on their reported specificities in rats and mice. To identify the receptor responsible for BK-induced plasma extravasation in NK1-R(−/−), the B2-R antagonist HOE 140 (0.1 nmol kg−1 i.v.) was injected into the distal femoral vein 8–13 min prior to EB/agonist injection. For time course experiments (rats), SP (4 nmol kg−1) was injected 0–10 min prior to transcardiac perfusion, while EB circulation time remained constant (5 min).

Cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats

Anaesthetized rats were continuously infused with cerulein (10 μg kg h−1) or carrier (0.9% NaCl) via a (PE-10) jugular vein catheter. After 2 h, EB (30 mg kg−1 of a 3% solution suspended in 0.9% NaCl) was injected into the femoral vein and animals were perfused 5 min later as described. Blood (0.2 ml) was removed before and after cerulein infusion and serum was assayed for amylase. In some experiments the NK1-R antagonists CP 96,345 or RP 67580 (both at 1 μmol kg h−1 i.v.) or carriers (controls) were continuously infused through a cannula in the contralateral jugular vein.

Monastral blue

The colloidal dye Monastral blue passes through endothelial gaps and becomes lodged in the basement membrane of leaky blood vessels (McDonald, 1994). It was used to confirm that cerulein-induced EB accumulation in the rat pancreas was due to leakage from the vasculature, and to identify the site of leakage. After 4 h of cerulein infusion, Monastral blue (30 mg kg−1 of a 3% solution suspended in 0.9% NaCl) was injected into the femoral vein and tissues were processed as previously described (Figini et al., 1997).

Cerulein-induced pancreatitis in mice

Cerulein (50–100 μg kg−1 i.p.) was injected each hour for 6–12 h. Animals were then anaesthetized, and EB (0.6%) was injected into the femoral vein. Blood (0.1 ml) was removed for serum amylase determination. Following transcardiac perfusion, the pancreas, stomach, duodenum, and proximal colon were collected to determine the tissue-specificity of cerulein-induced EB accumulation.

Myeloperoxidase determination

Neutrophil sequestration in pancreas and lung in mice was quantified by measuring tissue myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity. For these measurements, tissue samples removed at the time of sacrifice were stored at −70°C. They were thawed, homogenized in 2 ml of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.5% HTAB, centrifuged (10,000×g, 20 min, 4°C) and the supernatant was used for the MPO assay. The reaction mixture consisted of a 50 μl aliquot of this extracted enzyme, 1.6 mM tetramethylbenzidine, 80 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.4), and 0.3 mM hydrogen peroxide. For lung specimens, this mixture was incubated at 37°C for 110 s and the absorbance at 655 nm was measured. This absorbance was then corrected for the dry weight of the tissue sample used and results were expressed as activity per unit of dry weight. For pancreas specimens, the reaction mixture was allowed to continue for 30 min at 37°C and the final change in absorbance was used to calculate pancreas MPO activity.

Histology

The severity of pancreatitis was assessed by a pathologist who was unaware of the experimental design. NK1-R(+/+) and NK1-R(−/−) mice were treated with cerulein for 12 h and then allowed to recover for 16 h. Animals were anaesthetized, and the pancreas was removed, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin blocks, and sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Blood pressure monitoring

A length of PE-10 tubing was inserted into the carotid artery of anaesthetized animals and connected to a digital blood pressure analyser (Squibb Viatek, Hillsboro, OR, U.S.A.) and pressure transducer (Custom Transpac, Abbott Critical Care Systems, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was recorded at 2 min intervals.

Amylase determination

Amylase concentration in serum was assayed for each experimental group of animals using an α-amylase assay kit (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean. Differences between groups were examined using one-way analysis of variance and Student-Newman Keuls test for multiple groups, with P<0.05 considered significant.

Results

Rats

Effect of tachykinins and neurokinin receptor antagonists on pancreatic EB

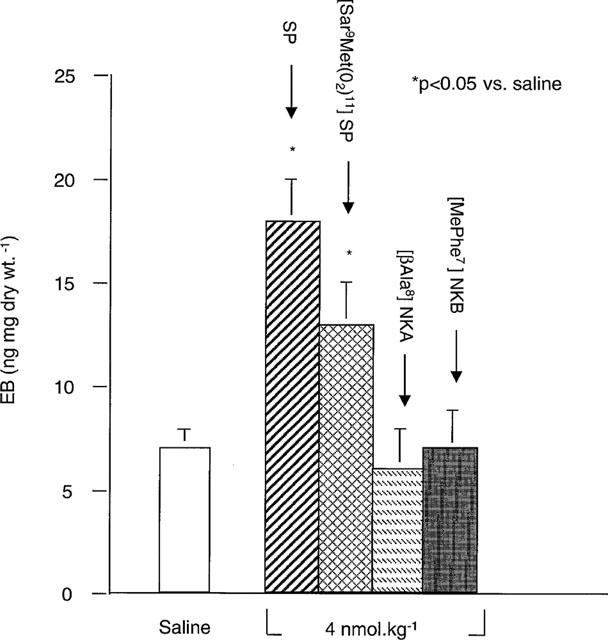

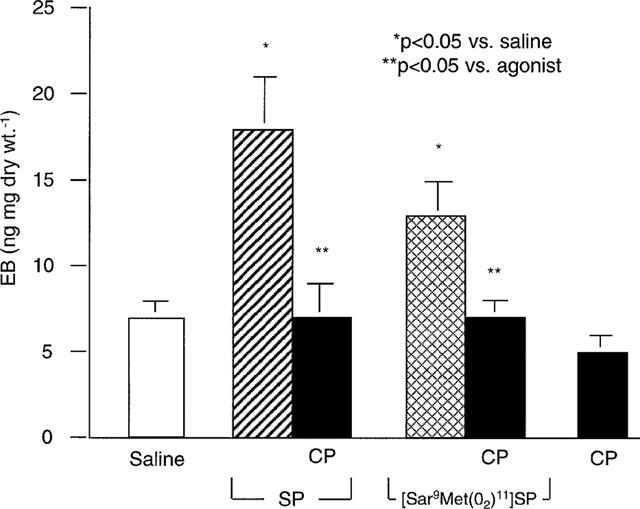

The extravasation of plasma into the pancreatic interstitium was quantified using EB. SP increased EB in rat pancreas (Figure 1). In preliminary studies, the peak effect occurred with 4 nmol kg−1, and this dose was used subsequently. The NK1-R specific agonist [Sar9 Met(O2)11]SP increased EB in the pancreas, while the NK2-R and NK3-R specific agonists, [βAla8]NKA and [MePhe7]NKB respectively, had no effect (Figure 1). The NK-1R antagonist CP 96345 completely blocked the effects of SP and [Sar9 Met(O2)11]SP on pancreatic EB accumulation (Figure 2). The antagonist alone had no effect. Thus SP stimulates EB accumulation in the rat pancreas via the NK1-R. The NK2-R and NK3-R do not mediate plasma extravasation in this tissue. Peak effect occurred 5 min after bolus injection of SP (18±3 ng mg dry wt−1 at 5 min vs 7±1 and 8±1 ng mg dry wt−1 at 0 and 2.5 min, respectively, n=8/group) and the response was attenuated by 10 min (14±2 ng mg dry wt−1, n=7). This suggests that SP-induced plasma extravasation in the pancreas is rapid in onset and rapidly attenuated.

Figure 1.

Effect of tachykinins on EB in rat pancreas. SP, the NK1-R selective agonist [Sar9Met(O2)11]SP, the NK2-R agonist [βAla8]NKA, the NK3-R agonist [MePhe7]NKB (all 4 nmol kg−1) or saline were injected i.v. concurrent with EB injection. Data are means± s.e.mean; n=6–8 per group.

Figure 2.

Effect of NK1-R antagonism on tachykinin-induced EB in rats. SP (4 nmol kg−1), the NK-1 agonist [Sar9 Met(O2)11]SP (4 nmol kg−1), or saline was injected i.v. alone or after injection of the NK1-R antagonist CP 96345 (1 μmol kg−1). Data are means±s.e.mean; n=6–8 per group.

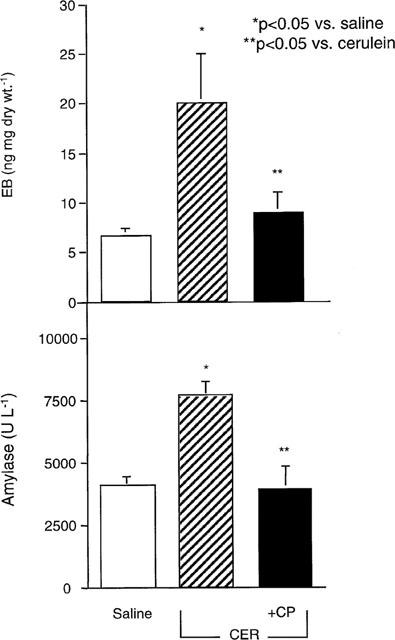

Effect of NK1-R antagonism on cerulein-induced Eb and hyperamylasemia

Cerulein stimulated a marked rise in EB in rat pancreas (Figure 3). Cerulein-induced EB was similar in magnitude to the peak levels of extravasation induced with SP (Figure 1). In preliminary studies after 1, 2, 4, and 6 h (data not shown), peak accumulation of EB occurred at 2 h and therefore this time was selected for the remaining experiments. The NK-1R antagonist CP 96,345 blocked cerulein-induced EB accumulation in the pancreas (Figure 3A). The antagonist alone had no effect (data not shown). Cerulein also significantly increased serum amylase by 2 h, and this effect was blocked by the NK1-R antagonist CP 96345 (Figure 3B). The NK1-R antagonist RP 67580 completely blocked cerulein-induced plasma extravasation (6.7+0.8, n=6). The antagonists alone had no effect. Thus, cerulein-induced plasma extravasation and hyperamylasemia depend on activation of the NK1-R.

Figure 3.

Effect of NK1-R antagonism on cerulein-induced EB and serum amylase in rats. Cerulein (10 μg kg h−1) or saline was continuously infused i.v. alone, or with the NK1-R antagonist CP 96345 (1 μmol kg h−1) for 2 h. Data are means±s.e.mean; n=6 per group.

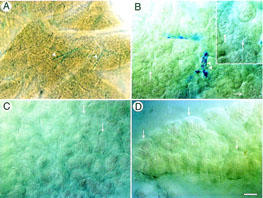

Effect of cerulein and NK1-R antagonism on pancreatic Monastral blue

Cerulein induced the deposition of Monastral blue in the basement membrane of small and large blood vessels in the rat pancreas (Figure 4A,B). The NK1-R antagonist CP 96345 abolished Monastral blue deposition in the pancreas of cerulein-treated rats (Figure 4D). Monastral blue was not apparent in trachea, bladder or stomach from cerulein-treated animals. Thus, cerulein induces the formation of endothelial gaps in pancreatic blood vessels via activation of the NK1-R.

Figure 4.

Monastral blue pigment deposition in whole mounts of rat pancreas treated with cerulein (10 μg kg h−1) (A,B), saline (C), or cerulein+the NK1-R antagonist CP 96345 (1 μmol kg h−1) (D) for 4 h. In cerulein-treated animals, Monastal blue was visible in small and large vessels (arrowheads) within pancreatic lobules (A), and at higher magnification the outlines of endothelial cells were evident confirming deposition in the basement membrane (B). Areas of vacuolization were also seen (arrows, insert). In saline-treated animals, no Monastral blue was evident and intact acini were apparent (arrows) (C). Tissues from animals treated with cerulein+the NK1-R antagonist had no detectable Monastral blue (D). (Images B–D are with DIC filters, bar is 185 mm in A, 30 μm in B–D).

Mice

We have previously shown that SP stimulates plasma extravasation in normal mouse pancreas, and this response is blocked by pharmacologic antagonism of the NK1-R (Figini et al., 1997). In the present series of experiments, we studied this response in mice in which the NK1-R has been deleted by homologous recombination.

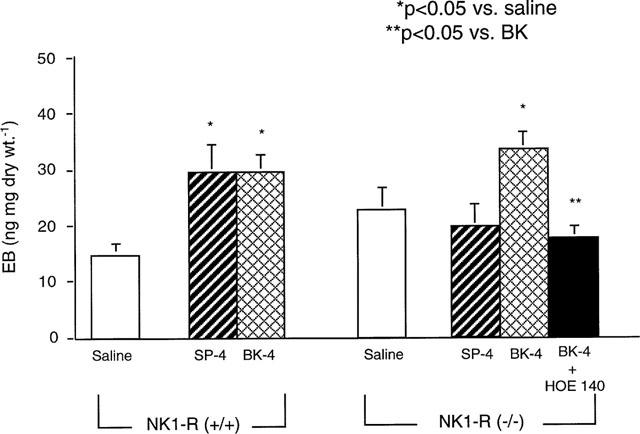

Effect of SP on EB in NK1-R(+/+)/(−/−) mice

To confirm the presence of functional NK1-R's in wildtype mice, and their absence in knockout mice, we measured pancreatic EB in response to SP. A bolus injection of SP (4 nmol kg−1) increased EB in the pancreas 2 fold in NK1-R(+/+) mice (Figure 5). We have previously shown that plasma extravasation induced by the bolus injection of SP is blocked by pharmacologic antagonism of the NK1-R (Figini et al., 1997). We confirmed this finding in the present study. Thus, the NK1-R antagonist SR 140333 significantly reduced SP-induced plasma extravasation in NK1-R(+/+) mice (SP+SR: 30+2 vs SP (10 nmol kg−1): 54+5 ng mg−1 dry wt, n=6 per group, P<0.05). SP had no effect on EB in NK1-R(−/−) mice (Figure 5). Thus SP stimulates plasma extravasation in NK1-R(+/+) mice via activation of the NK1-R.

Figure 5.

Effect of SP and BK on EB in NK1-R(+/+)/(−/−) mice. SP (4 nmol kg−1), BK (4 nmol kg−1), or saline was injected i.v. in both NK1-R(+/+) and NK1-R(−/−) mice. In some cases, the B2-R antagonist HOE 140 (1 nmol kg−1) was injected prior to agonist. Data are means±s.e.mean; n=4 per group.

We treated NK1-R(−/−) mice with bradykinin (BK) to verify that they are capable of pancreatic plasma extravasation. BK (4 nmol kg−1) induced a 100% increase in EB in NK1-R(+/+) mice, and a 50% increase in EB in NK1-R(−/−) mice (Figure 5). BK-induced EB accumulation in knockout mice was abolished by pre-treatment with the B2-R antagonist HOE 140 and therefore is mediated by the B2-R. Thus, NK1-R(−/−) mice are still capable of pancreatic plasma extravasation via an NK1-R–independent pathway.

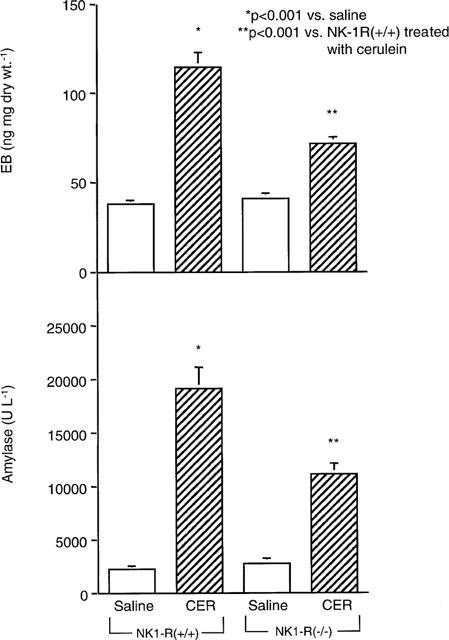

Effect of cerulein on EB, amylase and MPO in NK1-R(+/+)/(−/−) mice

In wild-type mice cerulein (50 μg kg h−1 for 12 h) induced a 3 fold rise in EB in the pancreas (Figure 6A). Genetic deletion of the NK1-R reduced cerulein-induced plasma extravasation by 60%. Cerulein induced a 10 fold rise in serum amylase in NK1-R(+/+) mice, and this response was attenuated by 60% in NK1-R(−/−) animals (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Effect of cerulein on EB (n=7–12) and serum amylase (n=11–18) in NK1-R(+/+)/(−/−) mice. Cerulein (50 μg kg −1) or saline was injected i.p. every hour for 12 h in NK1-R(+/+) or NK1-R(−/−) mice. Data are means±s.e.mean.

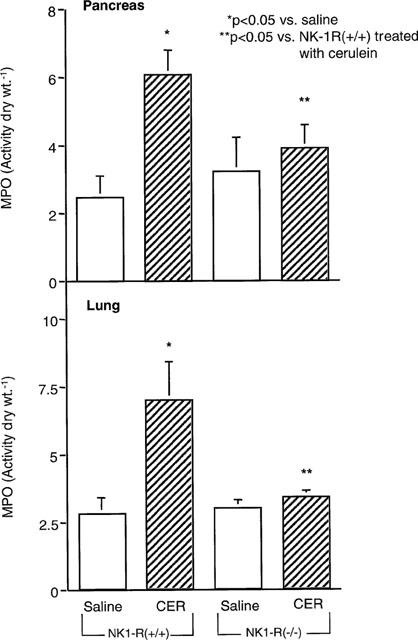

In the pancreas, cerulein (50 μg kg h−1 for 12 h) induced a 2.5 fold rise in the neutrophil marker MPO in NK1-R(+/+) mice, whereas only a 1.3 fold increase in pancreatic MPO was observed in NK1-R(−/−) mice (Figure 7A). Similarly, in the lung, cerulein stimulated a 2.5 fold increase in MPO in NK1-R(+/+) mice, while only a 1.2 fold increase was seen in NK1-R(−/−) animals (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Effect of cerulein on MPO activity in pancreas and lung from NK1-R(+/+)/(−/−) mice (n=4–6 per group). Cerulein (50 μg kg h−1) or saline was injected i.p. every hour for 12 h in NK1-R(+/+) or NK1-R(−/−) mice. Data are means±s.e.mean.

Cerulein had no effect on EB in stomach, duodenum, or proximal colon in either NK1-R(+/+) or (−/−) mice (data not shown). This result suggests that cerulein-induced inflammatory oedema in the pancreas is due to alterations in the pancreatic microvasculature, rather than the result of a systemic increase in vascular permeability.

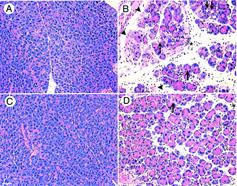

Effect of cerulein on histologic changes in NK1-R(+/+)/(−/−) mice

After 12 h of cerulein (50 μg kg h−1 for 12 h), NK1-R(+/+) mice developed oedema, neutrophil infiltration, haemorrhage and acinar necrosis (Figure 8B). In NK1-R(−/−) mice treated with 12 h of cerulein, acinar necrosis, oedema and neutrophil infiltration were all less severe than in NK1-R(+/+) animals (Figure 8D). Tissues from saline-treated NK1-R(+/+) and (−/−) mice appeared histologically normal.

Figure 8.

Effect of cerulein on histologic severity of acute pancreatitis in NK1-R(+/+) (A,B) and NK1-R(−/−) (C,D) mice. After 12 h of saline (A,C) or cerulein (B,D) administration, histologic sections of the pancreas were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. NK1-R(+/+) animals treated with cerulein (B) developed interlobar and intralobular oedema, neutrophil infiltration, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and acinar necrosis. Pancreatic sections from cerulein-treated NK1-R(−/−) mice (D) had less severe inflammation, as evidenced by reduced oedema, vacuolization, neutrophil infiltration and acinar necrosis. Saline-treated animals appeared normal (A,C). Bar is 100 μm.

Blood pressure

MAP in anaesthetized rats was 70–90 mmHg and in mice was 50–70 mmHg. Neither continuous infusion of SP (100 pmol kg h−1, 30 min) nor bolus injection of SP (4 nmol kg−1) had any effect on MAP in either species (n=3/group). Thus, SP-induced EB is unlikely to result from a systemic haemodynamic effect of SP in the present study.

Discussion

Our results show that SP, acting via the NK1-R, is an important mediator of inflammatory oedema, hyperamylasemia and the histologic changes that characterize cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats and mice. We have demonstrated that (1) the tachykinin SP induces plasma extravasation in the pancreas via activation of the NK1-R in both rats and mice, (2) pharmacologic antagonism of the NK1-R attenuates cerulein-induced hyperamylasemia, pancreatic plasma extravasation and histologic severity in rats, and (3) genetic deletion of the NK1-R reduces the magnitude of cerulein-induced plasma extravasation and inflammation in mouse pancreas. Together, our data suggest that neurogenic mechanisms enhance the severity of cerulein-induced pancreatitis.

Extravasation of plasma from the intravascular to the interstitial space in the pancreas occurs within minutes of cerulein infusion (Klar et al., 1994). Our data indicate that activation of the NK1-R by SP is an important mechanism in pancreatic plasma extravasation. First, the naturally-occurring NK1-R agonist, SP, induced plasma extravasation in the pancreas of both rats and mice. Second, the NK1-R selective agonist [Sar9 Met(O2)11]SP, but not NK2-R or NK3-R selective agonists, induced dose-related increases in EB in rat pancreas. These observations are supported by the findings that SP, but not agonists of the NK2-R or NK3-R, stimulated EB accumulation in the pancreas of conscious rats (Nicolau et al., 1993). Third, plasma extravasation induced by SP or the NK1-R selective agonist was inhibited by antagonism of the NK1-R in rats and NK1-R(+/+) mice. We have previously shown that NK1-R antagonism blocks SP-induced plasma extravasation in Swiss-Morini mice (Figini et al., 1997). Fourth, genetic deletion of the NK1-R abolished SP-induced EB in mice. Thus, the NK1-R mediates SP-induced plasma extravasation in both rats and mice.

This is the first study, of which the authors are aware, that directly links the NK1-R to acute pancreatitis in the rat. The effects of SP vary among different species (Otsuka & Yoshioka, 1993). We have previously shown that SP inhibits exocrine secretion in the isolated, vascularly-perfused rat pancreas (Kirkwood et al., 1999). In the present study, we determined if SP is a pro-inflammatory mediator in the rat pancreas. Cerulein-induced plasma extravasation, hyperamylasemia and histologic damage were blocked by antagonism of the NK1-R in rats. We observed near-complete inhibition of these parameters with both NK1-R antagonists, CP 96345 and RP 67580. Thus, SP-induced activation of the NK1-R is an important pro-inflammatory event in cerulein-induced pancreatitis in the rat. It has previously been shown that the bradykinin receptor antagonist HOE 140 blocks cerulein-induced pancreatic oedema in the rat (Griesbacher et al., 1993). Since bradykinin is known to release SP (Geppetti, 1993), this effect may be due, at least in part, to bradykinin-induced release of SP and activation of the NK1-R.

The effects of cerulein on plasma extravasation likely occur via release of intrapancreatic SP. In the present study, cerulein stimulated plasma extravasation in the pancreas but not in the stomach, duodenum or proximal colon. In contrast, systemic infusion of SP causes EB accumulation in many tissues, including stomach, duodenum, proximal colon, trachea, and bladder as well as pancreas (Figini et al., 1997; Nicolau et al., 1993). Thus, cerulein-induced, NK1-R-mediated, plasma extravasation in acute pancreatitis is likely due to intrapancreatic release of SP. Indeed, pancreatic SP levels increase markedly following cerulein administration (Bhatia et al., 1998). The mechanism by which cerulein stimulates the release of SP in the pancreas is unclear. In other tissues, various noxious chemical, mechanical or thermal stimuli stimulate the subpopulation of afferent neurons that contain SP, which is then released both centrally and peripherally, resulting in activation and internalization of the NK1-R (Mantyh et al., 1995; Bowden et al., 1994). We have previously shown that stimulation of sensory nerves by capsaicin, which releases SP, increases pancreatic EB by activating the NK1-R (Figini et al., 1997). It seems likely that sensory nerves are excited during acute pancreatitis leading to the release of intrapancreatic SP and activation of the NK1-R.

Our experiments using the intravascular tracer EB and the pigment Monastral blue indicate that one mechanism by which SP amplifies the severity of acute pancreatitis is by stimulating NK1-R-mediated plasma extravasation. The pattern of Monastral blue in the pancreas after cerulein treatment was similar to that found in rat trachea (Baluk et al., 1997), and stomach, duodenum and bladder of the mouse (Figini et al., 1997) following SP administration. Extensive characterization of the endothelium in rat trachea via scanning electron microscopy has shown that SP-induced plasma extravasation occurs via the formation of gaps between endothelial cells (McDonald et al., 1999). Thus, the pro-inflammatory effects of SP in cerulein-induced plasma extravasation are likely due to the known effects of this peptide on endothelial cells. Whether the pro-inflammatory effects of NK1-R activation on serum amylase, pancreatic MPO, and histologic severity are also due to an effect on endothelial cells, or perhaps occur via activation of the NK1-R on other cells, such as neurons, acinar or inflammatory cells, remains unknown.

We used several strategies to verify that EB accumulation was caused by plasma extravasation in the pancreas rather than increased delivery or diffusion of the dye. First, significant haemodynamic changes that might alter EB delivery to the pancreas were excluded by measurement of blood pressure. Second, by using gel chromatography, we found that nearly all intravascular EB was in the bound, rather than free, form, and was therefore not subject to passive diffusion. Third, the finding of Monastral blue pigment outlining endothelial cells of pancreatic venules in cerulein-treated rats confirms that cerulein-induced increases in EB accumulation in the pancreas are attributable to ‘leaky' vessels (Baluk et al., 1997).

The findings in the present study that NK1-R antagonism/deletion blocked cerulein-induced EB accumulation, Monastral blue deposition, MPO, hyperamylasemia and histologic alterations provide compelling evidence for the importance of neurogenic mechanisms in acute pancreatitis. We propose that sensory nerves in the pancreas are stimulated during acute pancreatitis leading to the release of SP. Binding of SP to the NK1-R induces the extravasation of plasma proteins and fluid into the pancreatic interstitium. In contrast to immune-mediated mechanisms of inflammation, neurogenic pathways are always present and can be rapidly activated. The importance of neurogenic pancreatic inflammation, with its attendant losses of fluid and proteins, in the course of human pancreatitis is the subject of future investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Edna Calaustro, Christopher Domush, Chuck Haugen and Michelle Randolph for their excellent technical assistance, and Donald McDonald and Peter Baluk for their helpful suggestions regarding interpretation of EB data. The NK1-R antagonist CP 96345 was from Pfizer, Inc. courtesy of Dr Saul B. Kadin (Groton, CT, U.S.A.). The B2-R antagonist HOE 140 was from Hoechst courtesy of Dr K. Wirth (Frankfurt, Germany). Monastral blue was a generous gift from Donald McDonald (UCSF). This manuscript is supported by NIH grants RO1 DK46285 (to K.S. Kirkwood), DK52388 (to E.F. Grady), DK07573 (to J. Maa and K.S. Kirkwood) and DK39957 (to N.W. Bunnett), and a grant from the Crohn's & Colitis Foundation (to N.W. Bunnett).

Abbreviations

- BK

bradykinin

- B2-R

Bradykinin-2 receptor

- EB

Evans blue

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NK1-R

neurokinin-1 receptor

- NK2-R

neurokinin-2 receptor

- NK3-R

neurokinin-3 receptor

References

- BALUK P., HIRATA A., THURSTON G., FUJIWARA T., NEAL C.R., MICHEL C.C., MCDONALD D.M. Endothelial gaps: time course of formation and closure in inflamed venules of rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L155–L170. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.1.L155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHATIA M., SALUJA A.K., HOFBAUER B., FROSSARD J.L., LEE H.S., CASTAGLIUOLO I., WANG C.C., GERARD N., POTHOULAKIS C., STEER M.L. Role of substance P and the neurokinin 1 receptor in acute pancreatitis and pancreatitis-associated lung injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:4760–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWDEN J.J., GARLAND A.M., BALUK P., LEFEVRE P., GRADY E.F., VIGNA S.R., BUNNETT N.W., MCDONALD D.M. Direct observation of substance P-induced internalization of neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors at sites of inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:8964–8968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOZIC C.R., LU B., HOPKEN U.E., GERARD C., GERARD N.P. Neurogenic amplification of immune complex inflammation. Science. 1996;273:1722–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE GIORGIO R., STERNINI C., WIDDISON A.L., ALVAREZ C., BRECHA N.C., REBER H.A., GO V.L. Differential effects of experimentally induced chronic pancreatitis on neuropeptide immunoreactivities in the feline pancreas. Pancreas. 1993;8:700–710. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMONDS-ALT X., DOUTREMEPUICH J.D., HEAULME M., NELIAT G., SANTUCCI V., STEINBERG R., VILAIN P., BICHON D., DUCOUX J.P., PROIETTO V., VAN BROECK D., SOUBRIE P., LE FUR G., BRELIERE J.C. In vitro and in vivo biological activities of SR140333, a novel potent non-peptide tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;250:403–413. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90027-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIGINI M., EMANUELI C., GRADY E.F., KIRKWOOD K.S., PAYAN D.G., ANSEL J., GERARD C., GEPPETTI P., BUNNETT N.W. Substance P and bradykinin stimulate plasma extravasation in the mouse gastrointestinal tract and pancreas. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:G785–G793. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARRET C., CARRUETTE A., FARDIN V., MOUSSAOUI S., PEYRONEL J.F., BLANCHARD J.C., LADURON P.M. Pharmacological properties of a potent and selective nonpeptide substance P antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:10208–10212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEPPETTI P. Sensory neuropeptide release by bradykinin: mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. Regul. Pept. 1993;47:1–23. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(93)90268-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIESBACHER T., TIRAN B., LEMBECK F. Pathological events in experimental acute pancreatitis prevented by the bradykinin antagonist, Hoe 140. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:405–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRKWOOD K.S., KIM E.H., HE X.D., CALAUSTRO E.Q., DOMUSH C., YOSHIMI S.K., GRADY E.F., MAA J., BUNNETT N.W., DEBAS H.T. Substance P inhibits pancreatic exocrine secretion via a neural mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:G314–G320. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.2.G314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLAR E., SCHRATT W., FOITZIK T., BUHR H., HERFARTH C., MESSMER K. Impact of microcirculatory flow pattern changes on the development of acute edematous and necrotizing pancreatitis in rabbit pancreas. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1994;39:2639–2644. doi: 10.1007/BF02087702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANTYH P.W., DEMASTER E., MALHOTRA A., GHILARDI J.R., ROGERS S.D., MANTYH C.R., LIU H., BASBAUM A.I., VIGNA S.R., MAGGIO J.E., SIMONE D.A. Receptor endocytosis and dendrite reshaping in spinal neurons after somatosensory stimulation. Science. 1995;268:1629–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.7539937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARINGHINI A., CIAMBRA M., PATTI R., RANDAZZO M.A., DARDANONI G., MANCUSO L., TERMINI A., PAGLIARO L. Ascites, pleural, and pericardial effusions in acute pancreatitis. A prospective study of incidence, natural history, and prognostic role. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1996;41:848–852. doi: 10.1007/BF02091521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDONALD D.M. Endothelial gaps and permeability of venules in rat tracheas exposed to inflammatory stimuli. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:L61–L83. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.1.L61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDONALD D.M., THURSTON G., BALUK P. Endothelial gaps as sites for plasma leakage in inflammation. Microcirculation. 1999;6:7–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICOLAU M., SIROIS M.G., BUI M., PLANTE G.E., SIROIS P., REGOLI D. Plasma extravasation induced by neurokinins in conscious rats: receptor characterization with agonists and antagonists. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1993;71:217–221. doi: 10.1139/y93-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OTSUKA M., YOSHIOKA K. Neurotransmitter functions of mammalian tachykinins. Physiol. Rev. 1993;73:229–308. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARIA A., LUNDBERG J.M. Evans blue fluorescence: quantitative and morphological evaluation of vascular permeability in animal tissues. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1983;8:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(83)90050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]