Abstract

The antisecretory effects of flufenamate in the rat distal colon were investigated with the Ussing-chamber and the patch-clamp method as well as by measurements of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration using fura-2-loaded isolated crypts.

Flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1) suppressed the short-circuit current (Isc) induced by carbachol (5•10−5 mol l−1), forskolin (5•10−6 mol l−1) and the Isc induced by the membrane-permeable analogue of cyclic AMP, CPT–cyclic AMP (10−4 mol l−1).

Indomethacin (10−6–10−4 mol l−1) did not mimic the effect of flufenamate, indicating that the antisecretory effect of flufenamate is not related to the inhibition of the cyclo-oxygenase.

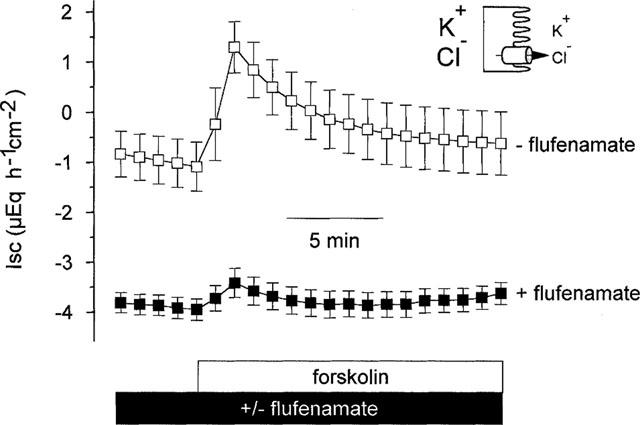

When the basolateral membrane was depolarized by a high K+ concentration and a Cl− current was induced by a mucosally directed Cl− gradient, the forskolin-stimulated Cl− current was blocked by flufenamate, indicating an inhibition of the cyclic AMP-stimulated apical Cl− conductance.

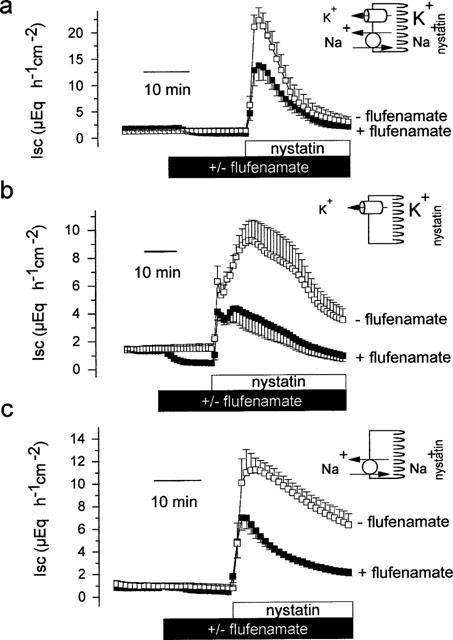

When the apical membrane was permeabilized by the ionophore, nystatin, flufenamate decreased the basolateral K+ conductance and inhibited the Na+–K+-ATPase.

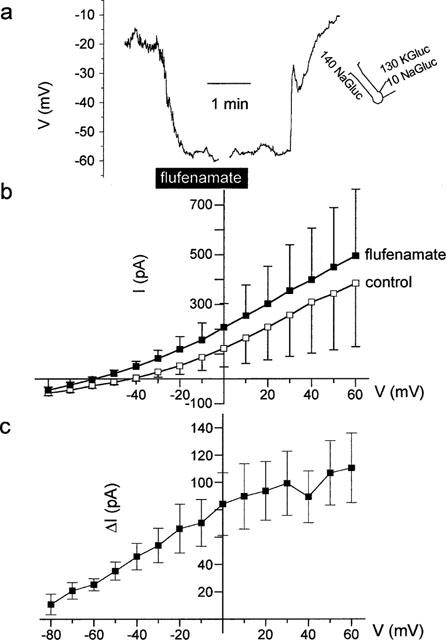

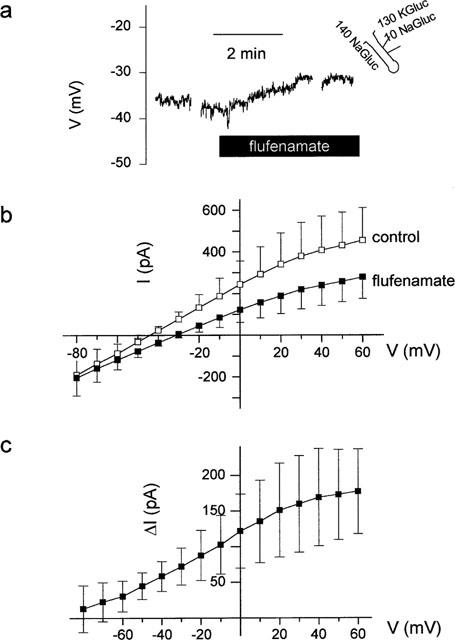

Patch-clamp experiments revealed a variable effect of flufenamate on membrane currents. In seven out of 11 crypt cells the drug induced an increase of the K+ current, whereas in the remaining four cells an inhibition was observed.

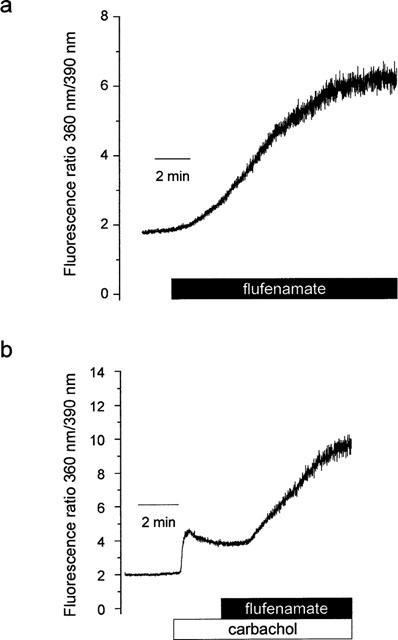

Experiments with fura-2-loaded isolated crypts indicated that flufenamate increased the basal as well as the carbachol-stimulated intracellular Ca2+ concentration.

These results demonstrate that flufenamate possesses multiple action sites in the rat colon: The apical Cl− conductance, basolateral K+ conductances and the Na+–K+-ATPase.

Keywords: cyclic AMP, Cl− channels, flufenamate, intracellular Ca2+, K+ channels, Na+–K+-ATPase, rat colon

Introduction

In a recent study, we investigated the properties of a Ca2+ entry pathway in rat colonic epithelium (Frings et al., 1999). Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores either by the intracellular Ca2+ chelator ethyleneglycol bis-(β-aminoethylether) N,N,N′,N′-eteraacetic acid) (EGTA) or the stable acetylcholine derivative, carbachol, activated a non-selective cation conductance, which proved to be responsible for the influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular medium. This conductance had therefore properties of store-activated Ca2+ channels observed in other non-excitable tissues (Parekh & Penner, 1997).

In the course of these experiments, several well known blockers of non-selective cation channels, e.g. La3+, Gd3+ and flufenamate, were used. However, their actions proved to be quite disparate. Whereas the two lanthanides, La3+ and Gd3+, inhibited a current with a reversal potential of 0 mV as expected for a non-selective cation conductance with equal cation concentrations on both sides of the membrane, the current inhibited by flufenamate exhibited a much more negative reversal potential (−32 mV), suggesting a distinct site of action. Therefore, the aim of the present investigations was to clarify the site of action of this blocker.

Several potential mechanisms of action of flufenamate have been described in the literature. Like other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, flufenamate blocks the cyclo-oxygenase, thus decreasing the endogenous production of prostaglandins (Insel, 1990). In several tissues and cell lines the inhibition of a non-selective cation conductance by flufenamate has clearly been shown (Gögelein & Greger, 1986; Gögelein et al., 1990; Kerst et al., 1995; Weiser & Wienrich, 1996). A third action observed is the inhibition of Cl− channels (Gögelein et al., 1987; Martin & Shuttleworth, 1994; Schumacher et al., 1995; Weber et al., 1995). Divergent interactions have been reported with K+ conductances, i.e. both an inhibition or activation, depending on the tissue studied (Wieser & Wienrich, 1996; Xu et al., 1994).

Consequently, in the present study the effects of flufenamate in the rat distal colon were investigated with the Ussing-chamber and the patch-clamp method as well as by measurements of intracellular Ca2+ concentration using fura-2-loaded isolated crypts.

Methods

Solutions

The Ussing-chamber experiments were carried out in a bathing solution containing (mmol l−1): NaCl 107, KCl 4.5, NaHCO3 25, Na2HPO4 1.8, NaH2PO4 0.2, CaCl2 1.25, MgSO4 1 and glucose 12. The solution was gassed with a gas mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2; the pH was 7.4. Lanthanides are known to be bound by CO32−- and PO43−-anions present in this solution (Caldwell et al., 1998). Therefore Ussing chamber studies in the presence of La3+ were carried out in a Tyrode bathing solution, containing (mmol l−1): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.25, MgSO4 1, glucose 12, HEPES (N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-2-ethansulphonic acid) 10 and gassed with O2. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH or HCl. Both Ussing chamber bathing solutions were kept at a temperature of 37°C.

For the depolarization of the basolateral membrane, a 111.5 mmol l−1 KCl solution was used, in which NaCl was equimolarly replaced by KCl. In order to apply a K+ gradient, the KCl concentration in the standard HCO3−-buffered solution was increased to 13.5 mmol l−1 while reducing the NaCl concentration to 98 mmol l−1 in order to maintain isoosmolarity. For the Na+-free solution, Na+ was replaced by N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG+). In the Cl−-free buffer, Cl− was substituted by gluconate. For the uptake experiments, KCl was replaced by RbCl.

For the experiments with isolated crypts the following buffers were used. The EDTA solution for the crypt isolation contained (mmol l−1): NaCl 107, KCl 4.5, NaH2PO4 0.2, Na2HPO4 1.8, NaHCO3 25, EDTA (ethylene diamino tetraacetic acid) 10, glucose 12, with a 1 g l−1 bovine serum albumin. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 by tris-base (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane). The high K+ Tyrode for the storage of the crypts consisted of (mmol l−1): K gluconate 100, KCl 30, NaCl 20, CaCl2 1.25, MgCl2 1, HEPES 10, glucose 12, Na pyruvate 5 and 1 g l−1 bovine serum. The solution was adjusted with KOH to a pH of 7.4. The medium for the superfusion of the crypts was a Tyrode solution containing (mmol l−1): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.25, MgCl2 1, glucose 12, HEPES 10. The pipette solution was a K gluconate/KCl solution, which contained (mmol l−1): K gluconate 100, KCl 30, NaCl 10, MgCl2 2, EGTA (ethyleneglycol bis-(β-aminoethylether) N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid) 0.1, Tris 10, ATP (adenosine 5′-triphosphate disodium salt) 5; pH was 7.2. In experiments where a high Ca2+-buffering capacity was needed, the pipette solution contained (mmol l−1) EGTA 11 together with CaCl2 1. When a Cl−-free intracellular condition was necessary, KCl and NaCl of the standard pipette solution were substituted by K gluconate (KGluc) and Na gluconate (NaGluc), respectively. For cation substitution Na+ and K+ were replaced by NMDG+.

Tissue preparation

Wistar rats were used with a weight of 180–220 g. The animals had free access to water and food until the day of the experiment. Animals were stunned by a blow on the head and killed by exsanguination (approved by Regierungspräsidium Gießen, Gießen, Germany). The serosa and muscularis propria were stripped away by hand to obtain the mucosa-submucosa preparation of the distal part of the colon descendens. Two distal and two proximal segments of the colon of each rat were prepared. In general, one tissue from each localization served as control and the other was treated with flufenamate.

Short-circuit current measurement

The tissue was mounted in a modified Ussing-chamber, bathed with a volume of 3.5 ml on each side of the mucosa and short-circuited by a voltage clamp (Aachen Microclamp, AC Copy Datentechnik, Aachen, Germany) with correction for solution resistance. The exposed surface of the tissue was 1 cm2. Short-circuit current (Isc) was continuously recorded and tissue conductance (Gt) was measured every min. Isc is expressed as μEq h−1 cm−2, i.e. the flux of a monovalent ion per time and area with 1 μEq h−1 cm−2=26.9 μA cm−2. Tissues were left for 1 h to stabilize Isc, before the effect of drugs was studied. The baseline in electrical parameters was determined as mean over 3 min just before administration of a drug.

Uptake experiments

Uptake experiments were performed similar as described previously (Diener et al., 1996). The measurement of basolateral Rb+ uptake was started after an equilibration period of 60 min in Lucite chambers with a volume of 2.5 ml on each side of the tissue. When the uptake was measured in the presence of test substances, the drugs were administered 10 min prior to the addition of 86Rb+ (22 kBq) to the serosal side of the chamber. Five min after administration of 86Rb+ standards were taken from the labelled side and the uptake was stopped by washing the chamber with 20 ml of fresh, unlabelled buffer solution on both sides. The tissue was removed from the chamber and blotted on filter paper. This procedure took 1–2 min. The tissue was solubilized in 1 ml 0.1 N HNO3 for 20 h at 70°C. After neutralization with 0.1 ml 1 N NaOH, the radioactivity in the sample was determined in a liquid scintillation counter. Results were calculated as uptake per area mucosa (nmol cm−2).

Crypt isolation

The mucosa-submucosa was fixed on a plastic holder with tissue adhesive and transferred for 8 min in the EDTA solution. The mucosa was vibrated once for 30 s in order to isolate intact crypts. The were collected in an intracellular-like high K+ Tyrode buffer (Böhme et al., 1991). The mucosa was kept at 37°C during the isolation procedure. All further steps including the patch-clamp experiments were carried out at room temperature.

Patch-clamp experiments

The crypts were pipetted into the experimental chamber (volume of the chamber 0.5 ml). The crypts were fixed to the glass bottom of the chamber with the aid of poly-L-lysine (0.1 g l−1). The preparation was superfused hydrostatically throughout the experiment (perfusion rate about 1 ml min−1). The chamber was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus IX-70).

Patch pipettes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass capillaries (Jencons Scientific Ltd., Bedfordshire, U.K.; outer diameter 2 mm, inner diameter 1 to 1.25 mm) on a two-stage puller (H. Ochotzki, Homburg/Saar, Germany). After fire-polishing, the tips had resistances of 5–10 MΩ when filled with the standard pipette solution. To obtain a whole-cell recording, the membrane patch under the tip of the pipette was broken by a stronger suction pulse after formation of the seal. Seal resistances were 5–10 GΩ. Membrane capacitance was corrected for by cancellation of the capacitance transient (subtraction) using a 50 mV pulse.

Patch-clamp currents were recorded on a RK-400 amplifier (Biologics, Meylan, France). Current and voltage signals were digitized at 48 kHz and stored on a modified digital audio recorder (DTR-1200, Biologics, Meylan, France). The reference point for the patch potentials was the extracellular side of the membrane assumed to have zero potential. Current-voltage (I-V) curves were obtained by clamping the cell to a holding potential of −80 mV and stepwise depolarization for 30 ms. After each depolarization, the cell was clamped again to the holding potential for 1 s before the following voltage step (incremented by 10 mV) was applied. For statistical comparison of membrane currents, outward current was measured at the end of a pulse depolarizing the cell for 30 ms from −80 to +60 mV, and inward current was measured at the holding potential of −80 mV.

Fura-2 measurements

Relative changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration were measured using the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye, fura-2 (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985) as described previously (Diener et al., 1991). The crypts were pipetted into the experimental chamber with a volume of about 3 ml. The crypts were fixed to the glass bottom of the chamber with the aid of poly-L-lysine. The crypts were loaded for 60 min with 2.5•10−6 mol l−1 fura-2/AM (fura-2-acetoxymethylester) in the presence of 0.05% Pluronic®. Then the fura-2 was washed away. The preparation was superfused hydrostatically throughout the experiment with NaCl Ringer. Perfusion rate was about 1 ml min−1.

Experiments were carried out at room temperature on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 35 M, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an epifluorescence and photometry set-up (FURA-2 Data Acquisition System, Luigs and Neumann, Feinmechanik und Elektrotechnik GmbH, Ratingen, Germany). The emission was measured between 470 and 540 nm from a field of about 20 μm diameter containing a fraction of a crypt fundus region. The cells were excited alternatively at 360 and 390 nm and the ratio of the emission signal at both excitation wavelengths was calculated. Data were sampled at 2 Hz. The baseline in the fluorescence ratio of fura-2 was measured for several minutes before drugs were administered by superfusion.

Drugs

Fura-2-acetoxymethylester (fura-2/AM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, U.S.A.) was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO; final concentration 2.5 ml l−1). Pluronic® (BASF, Weyandotte, U.S.A.) was dissolved in DMSO as a 200 g l−1 stock solution (final maximal DMSO concentration 2.5 ml l−1). Nystatin was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO; final concentration 2 ml l−1). Bumetanide, forskolin and indomethacin were added from ethanolic stock solutions (final maximal concentration 2.5 μl ml−1); carbachol and 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-adenosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate (CPT–cyclic AMP) were dissolved in aqueous stock solution and diluted in salt buffer just before use; flufenamate was dissolved in 0.5 mol l−1 NaOH. Pluronic® was purchased from Molecular Probes, Leiden, Netherlands. If not indicated differently, drugs were from Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany. Radioisotopes were obtained from NEN, Dreieich, Germany. The initial activity of 86Rb amounted to 411 GBq g−1.

Statistics

Results are given as means±one standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). When the means of several groups had to be compared, first an analysis of variances was performed. If the analysis of variances indicated significant differences between the groups investigated, further comparison was carried out by a Student's t-test (paired or unpaired as appropriate) or by the Mann–Whitney U-test. An F-test was applied to decide which test method was to be used.

Results

Effects of flufenamate on the Isc induced by secretagogues

In a first set of experiments the effect of flufenamate on the baseline short-circuit current (Isc) was investigated. After an equilibration time of 60 min, the rat distal colon exhibited an Isc of 1.7±0.4 μEq h−1 cm−2 (n=6). Flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) caused a significant decrease in basal Isc by 1.1±0.3 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6, Figure 1).

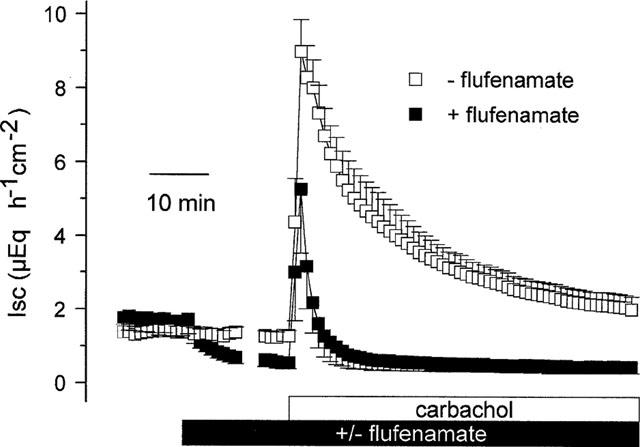

Figure 1.

Effect of carbachol (5•10−5 mol l−1 at the serosal side) on Isc in the absence and presence of flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side). The Isc is given during the flufenamate period for 10 min after administration of the inhibitor and for the last 5 min just prior to additional administration of carbachol. All Isc data points in between (which were in the range of 5–10 min depending on the individual tissue) were omitted. Values are means (symbols)±s.e.mean (error bars), n=6.

Carbachol (5•10−5 mol l−1 at the serosal side), which induces a Cl− secretion via an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (Diener et al., 1991), evoked a biphasic increase in Isc. Initially, the Isc increased to a peak of 7.7±0.7 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6, Figure 1) above baseline, which then declined slowly with a biphasic time behaviour as described previously (Strabel & Diener, 1995). Ten minutes after administration of the cholinergic agonist, the Isc was still elevated by 4.0±0.7 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6) under control conditions. When the tissue was pretreated with flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) the peak response to carbachol was significantly diminished (4.0±1.7 μEq h−1 cm−2; P<0.05 versus the peak response in the absence of flufenamate, U-test, n=6, Figure 1) and the decay of the current response was strongly accelerated, i.e. 10 min after administration of carbachol the Isc had returned completely to the former baseline.

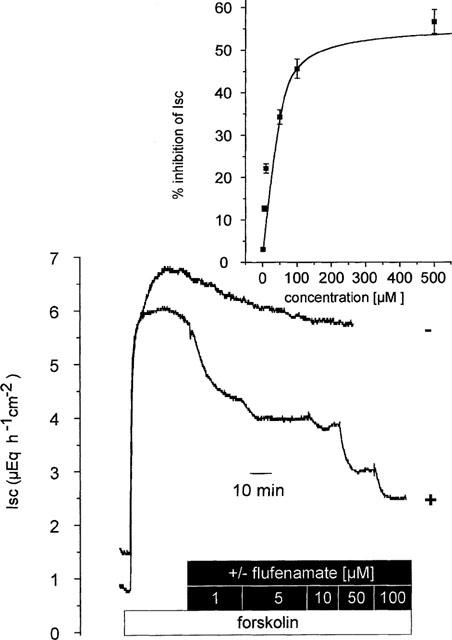

A similar inhibition was observed when a Cl− secretion was induced via an increase in the intracellular concentration of cyclic AMP by forskolin, an activator of the adenylate cyclase. The advantage of this forskolin-induced increase in Isc compared to carbachol is that the Cl− secretion stimulated via the cyclic AMP pathway remains stable over several hours (Mestres et al., 1990). Forskolin (5•10−6 mol l−1 at both sides) induced an increase in Isc of 3.3±0.6 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6, Figure 2). Flufenamate administered during the stable plateau period caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of the forskolin response (Figure 2). Analysis of the concentration-response curve revealed a half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 20±5 μmol l−1 and a maximal inhibition of 56±4%.

Figure 2.

Flufenamate concentration-dependently inhibited the Isc induced by forskolin (5•10−6 mol l−1 at both sides). The tracings are representative for six tissues, which received flufenamate (10−6–10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) in a cumulative matter (lower tracing), and six untreated tissues, which served as time dependent control (upper tracing). In a separate set of experiments flufenamate was administered in the concentration of 5•10−4 mol l−1. In contrast to the lower concentrations tested, 5•10−4 mol l−1 flufenamate evoked a first transient increase in Isc by 0.3±0.1 μEq h−1 cm−2 (n=6) within 2 min, before a decrease in Isc was observed. Inhibition of Isc by flufenamate was significant (P<0.05 vs time-dependent control, unpaired t-test,) for all concentrations tested. In the inset, the concentration-response curve is shown, which was fitted to a Michaelis-Menten kinetic using a half-maximal effective inhibitory concentration of 20±5 μmol l−1 and a maximal inhibition of Isc by 56±4%. Values are means±s.e.mean (error bars), n=6.

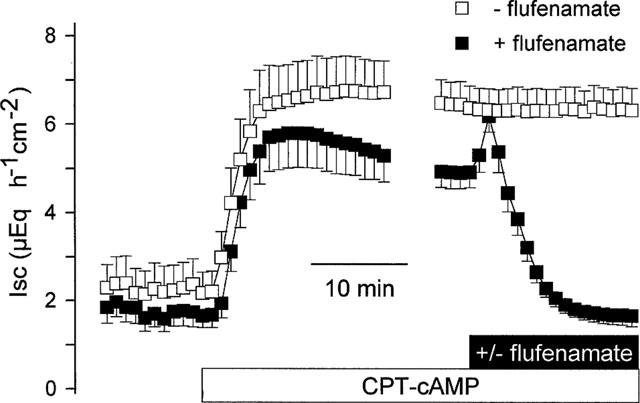

In order to stimulate a cyclic AMP-dependent Cl− secretion without an activation of the adenylate cyclase, the membrane permeable analogue of cyclic AMP, CPT–cyclic AMP (8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-adenosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate), was applied. CPT–cyclic AMP (10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) induced a stable increase in Isc from 1.8±0.3 to 4.9±0.4 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8, Figure 3), which was affected in a biphasic manner by flufenamate. Flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) evoked a first transient increase within 1–3 min of 1.7±0.3 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8), followed by a long-lasting inhibition of Isc. During this decrease the current fell to a value (1.7±0.2 μEq h−1 cm−2), which was no more significantly different from the former baseline (P>0.05, paired t-test, n=8, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) on Isc stimulated by CPT–cyclic AMP (8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-adenosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate, 10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side). After a transient activation, flufenamate abolished the Isc. This response was compared with a time-dependent control, which did not receive flufenamate. The Isc is given during the CPT–cyclic AMP period for 20 min after administration of the cyclic AMP analogue and for the last 5 min just prior to additional administration of flufenamate. All Isc data points in between (which were in the range of 5–10 min depending on each tissue) were omitted. Values are means (symbols)±s.e.mean (error bars), n=7.

Comparison with other blockers

A crucial step in the stimulation of Cl− secretion by carbachol is the activation of a non-selective cation conductance responsible for the influx of Ca2+ (Frings et al., 1999), leading to the opening of basolateral Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (Böhme et al., 1991). The resulting hyperpolarization increases the driving force for Cl− exit across spontaneously opening Cl− channels (Strabel & Diener, 1995). Consequently, the Isc induced by carbachol is sensitive to inhibition of the non-selective cation conductance (Frings et al., 1999) and sensitive to inhibition of cyclo-oxygenases, because the endogenous production of prostaglandins in the submucosal tissue is responsible for the activation of apical Cl− channels (Strabel & Diener, 1995). Flufenamate is a well known inhibitor of cyclo-oxygenases (Insel, 1990) and blocks non-selective cation channels in different cell types (Gögelein & Greger, 1986; Gögelein et al., 1990; Kerst et al., 1995; Weiser & Wienrich, 1996). Therefore, the effect of flufenamate was compared with those of a classical cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin, and La3+, a blocker of non-selective cation channels.

Indomethacin (10−4 mol l−1 at both sides) decreased the baseline Isc by 0.4±0.1 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=7). In the presence of indomethacin, forskolin (5–10−6 mol l−1 at both sides) induced an increase in Isc which amounted to 3.8±0.8 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=7). This response was not different from the effect of forskolin in the absence of indomethacin, in which forskolin increased Isc by 5.2±1.1 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P>0.05 versus the Isc response in the absence of indomethacin, unpaired t-test, n=7). In addition, no significant inhibition was observed, when indomethacin (10−4 mol l−1 at both sides) was applied during the plateau phase of the forskolin-stimulated Isc (n=7, data not shown) indicating that the inhibitory effect of flufenamate on the forskolin response is independent from the inhibition of the cyclo-oxygenase.

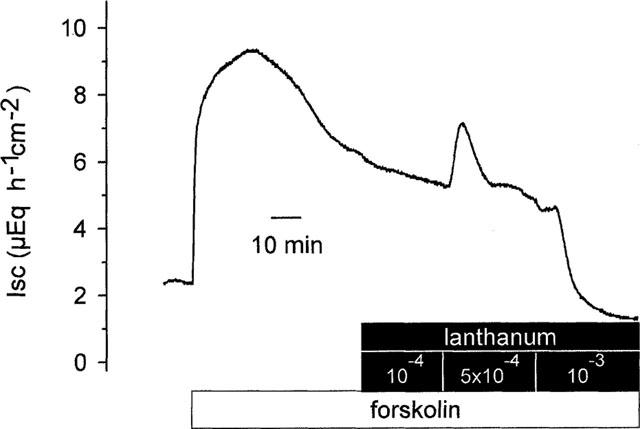

In a next set of experiments, the effect of flufenamate was compared with that of La3+. In order to exclude a binding of the lanthanide to CO32− and PO43− (Caldwell et al., 1998), these studies were performed in a Tyrode bathing solution. In contrast to indomethacin, La3+ inhibited the forskolin-induced Isc (Figure 4). In the Tyrode bathing solution, forskolin induced an increase in Isc to 5.7±0.5 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8). When La3+ was administered in increasing concentrations during the forskolin-induced plateau in Isc, a first significant effect was observed at a concentration of 5•10−4 mol l−1, at which the lanthanide induced a paradox, transient increase in Isc of 0.9±0.3 μEq h−1 cm−2 in five out of eight tissues. When the concentration of La3+ was increased to 10−3 mol l−1, after a transient increase of 0.7±0.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=5) the Isc fell to 2.6±0.5 μEq h−1 cm−2 which corresponds to an inhibition of the forskolin-induced secretion by 56±7% (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8). These results might either indicate that the antisecretory effect of flufenamate may be caused by the inhibition of non-selective cation channels or, alternatively, that an influx of Ca2+ across spontaneous open cation channels is necessary to maintain forskolin-induced Cl− secretion.

Figure 4.

Original record of the effect of La3+ (administered at the serosal side) on Isc stimulated by forskolin (5•10−6 mol l−1 at both sides). In five out of eight tissues, the inhibition of the forskolin-response by 10−3 mol l−1 La3+ was preceded by a transient stimulation of Isc, which amounted to 0.7±0.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=5). The tracing is typical for eight experiments with similar results.

Effect of flufenamate on the apical membrane

In order to investigate the effect of flufenamate on the apical Cl− conductance, the basolateral membrane was depolarized by a bathing solution containing a high K+ concentration and a Cl− current was driven by a mucosally directed Cl− gradient (see Methods). Changing the basolateral bathing solution to one which contained a high K+ concentration yielded a decrease in Isc, which reversed its normal polarity and reached negative values. When flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) was administered under these conditions, the drug decreased the Isc further from −1.8±0.3 μEq h−1 cm−2 to −3.9±0.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8). In the absence of flufenamate forskolin (5•10−6 mol l−1 at both sides) induced an increase in Isc due to the opening of apical Cl− channels, which amounted to 2.4±0.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6, Figure 5). In the presence of flufenamate, however, forskolin induced only an increase in Isc of 0.4±0.1 μEq h−1 cm−2 (n=8), which was significantly smaller (P<0.05 versus the Isc response in the absence of flufenamate, unpaired t-test) compared to the effect of forskolin in the absence of the blocker, indicating a direct inhibitory effect of flufenamate on the apical Cl− conductance.

Figure 5.

Effect of forskolin (5•10−6 mol l−1 at both sides) on Cl− currents in the absence and presence of flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) after basolateral depolarization (indicated by the schematic drawing). The serosal solution was a 111.5 mmol l−1 KCl buffer, the mucosal solution a 107 mmol l−1 NaGluc/4.5 mmol l−1 KGluc buffer. Flufenamate inhibits the current across the cyclic AMP-stimulated apical Cl− conductance. The Isc prior forskolin administration in the presence of flufenamate (−3.9±0.2 μEq h−1 cm−2, n=8) was significantly lower compared to the Isc in the absence of flufenamate (−0.9±0.5 μEq h−1 cm−2, n=6), indicating that even under basal conditions flufenamate blocks a Cl− conductance. Values are means (symbols)±s.e.mean (error bars), n=6–8.

Effects of flufenamate on the basolateral membrane

In order to reveal effects of flufenamate on the basolateral membrane, electrogenic K+ transport across the basolateral membrane was studied by use of the ionophore nystatin in order to bypass the apical membrane. In the presence of Na+ and of a serosally directed K+ gradient, nystatin (100 μg ml−1 at the mucosal side) evoked a strong increase in Isc, which rose to a peak value of 21.4±2.3 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8). When the tissue was pretreated with flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1) the effect of nystatin was decreased by about onethird, i.e. the increase in Isc amounted only to 14.1±2.4 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05 versus Isc response in the absence of flufenamate, unpaired t-test, n=9, Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Effects of flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) on currents across the basolateral membrane in tissues, which were apically permeabilized by nystatin (100 μg ml−1 at the mucosal side, indicated by the schematic drawing). (a) Total response of Isc to nystatin in the presence of Na+ and of a mucosal to serosal oriented K+ gradient (carried by the Na+–K+-ATPase and by current across basolateral K+ channels). The mucosal solution was a 98 mmol l−1 NaCl/13.5 mmol l−1 KCl buffer, the serosal solution was a 107 mmol l−1 NaCl/4.5 mmol l−1 KCl buffer. (b) Response of Isc to nystatin in the presence of a K+ gradient, but in the absence of Na+ (=current across basolateral K+ channels). The mucosal solution was a 98 mmol l−1 NMDGCl/13.5 mmol l−1 KCl buffer, the serosal solution was a 107 mmol l−1 NMDGCl/4.5 mmol l−1 KCl buffer. (c) Response of Isc to nystatin in the presence of Na+ but in the absence of a K+ gradient (=current carried by the Na+–K+-ATPase). The mucosal and the serosal solution was a 107 mmol l−1 NaCl/4.5 mmol l−1 KCl buffer. Values are means (symbols)±s.e.mean (error bars), n=6–9.

Two components contribute to the nystatin-induced increase in Isc: The first one represents a K+ current across basolateral K+ channels, and the second one is due to the electrogenic Na+–K+-ATPase (Schultheiss & Diener, 1997). Therefore in the next set of experiments, a current across basolateral K+ channels was driven by a mucosally to serosally oriented K+ gradient, and a current mediated by the Na+–K+-ATPase was abolished by replacing Na+ with the impermeable cation, N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG+). In the presence of a K+ gradient and in the absence of Na+ nystatin (100 μg ml−1 at the mucosal side) evoked a biphasic change in Isc. An immediate increase was followed by a delayed second increase, which decayed slowly with time. Pretreatment with flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) slightly reduced the height of the initial peak and reduced the second peak by more than half, i.e. 4.1±1.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 in the presence and 8.6±1.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 in the absence of flufenamate, respectively (P<0.05 versus the Isc response in the absence of flufenamate, unpaired t-test, n=6, Figure 6b) indicating a blockade of a basolateral K+ conductance by flufenamate. The reason for the biphasic nature of the K+ current induced by nystatin is unknown; possible reasons might be that after permeabilization of the apical membrane the cells might either activate swelling-sensitive or Ca+-sensitive K+ channels due to the known permeability of the ionophore for this divalent cation (see e.g. McNamara et al., 1999).

In order to reveal the action of flufenamate on the pump current, nystatin (100 μg ml−1 at the mucosal side) was administered in the presence of Na+ but in the absence of a K+ gradient. Permeabilization of the apical membrane, leading to a sudden increase in the intracellular Na+ concentration, stimulated a current mediated by the Na+–K+-pump of 12.9±1.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6, Figure 6c). In tissues pretreated with flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) this pump current was significantly diminished (6.9±0.8 μEq h−1 cm−2, P<0.05 versus current in the absence of flufenamate, unpaired t-test, n=6, Figure 6c). Thus, in addition to the effect on the K+ conductance, flufenamate exerted an inhibitory action on the Na+–K+-ATPase.

In an additional set of experiments, we investigated whether the administration of nystatin might induce a Cl− secretion in incompletely permeabilized cells, e.g. in the depth of the crypts, because nystatin has been shown to induce an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration of human colonic epithelium (McNamara et al., 1999). In the absence of Cl− and the presence of Na+ and a mucosally to serosally oriented K+ gradient (98 NaGluc 13.5 KGluc at the mucosal side and 108 NaGluc 4.5 KGluc at the serosal side), nystatin (100 μg ml−1 at the mucosal side) evoked an increase in Isc of 10.3±2.0 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=7). This current response was smaller compared to the effect of nystatin in the presence of Cl−, in which nystatin induced an increase in Isc of 21.4±2.3 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, unpaired t-test, n=8, see above). However, also under these conditions flufenamate (5•10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) inhibited the current evoked by the ionophore. When the tissue was pretreated with flufenamate in the absence of Cl−, nystatin evoked only an increase in Isc of 4.8±1.2 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05 versus Isc response in the absence of flufenamate, unpaired t-test, n=8), indicating that the inhibition of the nystatin effect cannot solely be due to the blockade of apical Cl− channels. When flufenamate was applied in the absence of Cl−, the drug evoked a stable decrease in Isc of 0.8±0.1 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8). However, in contrast to the effect of the drug in Cl−-containing buffer, this decrease was preceeded by a transient increase of 0.4±0.1 μEq h−1 cm−2 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6), which was observed in six out of eight tissues.

In order to investigate the effect of flufenamate on the basolateral membrane in more detail, uptake experiments were performed using 86Rb+ as marker for K+. Under control conditions, basolateral uptake amounted to 133.8±7.9 nmol cm−2 (n=6). Preincubation of the tissue with forskolin (5•10−6 mol l−1 at both sides) caused a small, insignificant increase of the uptake to 150.1±13.7 nmol cm−2 (P>0.05, analysis of variances followed by unpaired t-test, n=6). In the additional presence of flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1 at the serosal side) uptake was reduced to a value of 62.2±8.3 nmol cm−2 (P<0.05 versus uptake in the absence of any drugs, analysis of variances followed by unpaired t-test, n=6).

Effect of flufenamate on conductances of isolated crypts

Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed at isolated crypts to investigate the effect of flufenamate on K+ currents. Cl−-free pipette and perfusion solutions were used in order to rule out effects of the blocker on Cl− currents. Surprisingly the patch-clamp experiments revealed quite variable effects of flufenamate on membrane potential. In seven out of 11 crypt cells the membrane hyperpolarized in response to flufenamate, whereas in the remaining four cells a depolarization was observed. Therefore, the cells were divided in two groups: one which hyperpolarized and one which depolarized.

Seven cells responded with a hyperpolarization in the presence of flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) which in average amounted to 21±5 mV (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=7, Figure 7a). The change in membrane potential was partially reversible on washout of the drug. The hyperpolarization was paralleled by an increase in the membrane outward current (measured at +60 mV) from 385±256 to 496±268 pA (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=7, Figure 7b). The reversal potential of the flufenamate-activated current was −90±7 mV (Figure 7c), which is not significantly different from the calculated reversal potential of −84 mV for a K+ conductance under the chosen conditions. This indicates that flufenamate paradoxically activated a K+ conductance in this set of cells.

Figure 7.

(a) Hyperpolarization induced by flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) at a cell located at the fundus region of a crypt as indicated by the schematic drawing. The interruptions in the voltage tracing are caused by measurements of IV-relations in the voltage-clamp mode. (b) Membrane currents pooled from seven crypt cells, which responded to the presence of flufenamate with a hyperpolarization. (c) IV-relation of the current stimulated by flufenamate calculated from (b) as difference (Δ I) between the current in the presence – current in the absence of the drug. A Cl− free pipette solution (130 mmol l−1 KGluc/10 mmol l−1 NaGluc) and a Cl−-deprived superfusion solution (140 mmol l−1 NaGluc/5.4 mmol l−1 KCl) were used to suppress Cl− currents. Values are means (symbols)±s.e.mean (error bars), n=7.

In four other cells, however, flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) induced a depolarization of 16±6 mV (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=4, Figure 8a). The depolarization was accompanied by a decrease in outward current (Figure 8b), which however failed to reach statistical significance. Also the current inhibited by flufenamate exhibited a reversal potential which was close to the expected K+ reversal potential (Figure 8c). Consequently, flufenamate could either inhibit or activate cellular K+ conductances. It was not possible to correlate the type of response with the localization of the cell along the longitudinal axis of the crypt. However, a tendency was observed in as much as the majority of the hyperpolarizing cells was found at the lower part of the crypt.

Figure 8.

(a) Depolarization induced by flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) at a cell located in the middle region of crypt as indicated by the schematic drawing. The interruptions in the voltage tracing are caused by measurements of IV-relations in the voltage-clamp mode. (b) Membrane currents pooled from four crypt cells, which responded with a depolarization, in the absence and presence of flufenamate. (c) IV-relation of the current inhibited by flufenamate (Δ I) calculated from (b) as difference between the current in the absence–current in the presence of the drug. A Cl−-free pipette solution (130 mmol l−1 KGluc/10 mmol l−1 NaGluc) and a Cl−-free superfusion solution (140 mmol l−1 NaGluc) were used to suppress Cl− currents. Values are means (symbols)±s.e.mean (error bars), n=7.

Next we focused on a possible effect of flufenamate on the non-selective cation conductance responsible for Ca2+ entry into the colonic epithelial cells. The pipette solution contained NMDG gluconate as main electrolyte (see Methods) in order to suppress K+ and Cl− currents. The crypts were superfused with a solution containing dominantly Na gluconate. A non-selective capacitative cation was evoked by elevating the intracellular buffering capacity for Ca2+ in the pipette solution. The consequence of activating the store-operated non-selective cation conductance is an influx of Na+ across this pathway, which leads to a depolarization of the membrane (Frings et al., 1999). Indeed, basal membrane potential under these experimental conditions amounted only to −13±6 mV (n=10). When flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) was administered, the drug did not cause a hyperpolarization as one might expect, assuming that flufenamate blocks the non-selective cation conductance as described for other cells. In contrast, the cells further depolarized to a membrane potential of −4±5 mV (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=10). Also membrane inward current, which is carried mainly by an inflow of Na+ across the non-selective cation conductance, did not decrease. Instead, a small increase in inward current (measured at −80 mV) from −53±16 to −65±20 pA (difference not significant, paired t-test, n=10) was observed. These data suggest that flufenamate did not inhibit the store-operated non-selective cation conductance in rat colonic epithelium.

Effect of flufenamate on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration

The activation of a K+ conductance observed in seven out of 11 patch-clamp recordings might be based on an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, thereby stimulating the Ca2+-sensitive basolateral K+ conductance (Böhme et al., 1991). A similar effect of flufenamate was described for a mouse mandibular cell line, ST885 (Poronnik et al., 1992). Therefore measurements of relative changes in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration were performed by means of the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye, fura-2. Flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) induced an increase of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration in seven out of eight cells. The fluorescence ratio under baseline conditions amounted to 2.79±0.43 (n=8) which was significantly increased by flufenamate to 6.51±1.52 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=8, Figure 9a), indicating an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration induced by the drug under basal conditions.

Figure 9.

(a) Flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) caused an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration under basal conditions as indicated by an increase in the ration of the fluorescence signal of fura-2 excited at 360 and 390 nm. Typical for eight experiments with similar results. (b) Flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) further increased the carbachol-induced intracellular Ca2+ concentration as indicated by an increase of the fluorescence ratio (carbachol concentration: 5•10−5 mol l−1). Typical for 6–8 experiments with similar results.

Flufenamate did also not inhibit the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration evoked by the activation of a store-operated non-selective cation conductance due to carbachol (Frings et al., 1999). Carbachol caused an increase of the fluorescence ratio of fura-2 from 2.66±0.32 to 4.29±0.55 (n=6) as shown earlier (Diener et al., 1991, Frings et al., 1999). Flufenamate (10−4 mol l−1) administered during the plateau phase of the carbachol response caused a further increase of the fura-2 signal (Figure 9b). Five minutes after administration of the drug, the fluorescence ratio amounted to 6.34±0.77 (P<0.05, paired t-test, n=6, Figure 9b).

Finally, we tested the possibility that flufenamate interfered directly with the fluorescent dye and thereby altered the fluorescence ratio signal. However, when flufenamate was added to cell-free extracellular buffer containing free fura-2 acid, the fluorescence signal did not change (data not shown) excluding a non-specific interaction.

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate that flufenamate is an effective antisecretory drug in the rat distal colon. Flufenamate blocks Cl− secretion evoked by carbachol, forskolin or CPT–cyclic AMP. These secretagogues act via different mechanisms. Carbachol elevates the cellular Ca2+ concentration in a biphasic manner: a release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores is followed by an influx from the extracellular medium via activation of a non-selective cation conductance (Frings et al., 1999). The consequence is the opening of basolateral Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels (Böhme et al., 1991; Bleich et al., 1996) thereby enhancing the driving force for Cl− secretion through spontaneously opening Cl− channels (Strabel & Diener, 1995). These channels are kept open due to a basal synthesis of prostaglandins (Diener et al., 1988) leading to increased levels of the cellular cyclic AMP content (see e.g. Smith et al., 1987). An increase of the intracellular concentration of cyclic AMP can also be obtained by forskolin, a drug, which stimulates the adenylate cyclase. The consequence is the opening of apical Cl− channels via cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation (Hwang et al., 1994). Thus the observed antisecretory action of flufenamate could be due to an inhibition of the basal prostaglandin synthesis or due to the block of ion conductances, i.e. an apical Cl− conductance, a non-selective cation conductance or a basolateral K+ conductance involved in Cl− secretion.

Compared to the various ion conductances, the inhibitory effect of flufenamate on the cyclo-oxygenase is at least in these in vitro studies negligible as revealed by the comparison with the action of indomethacin, a drug, which belongs to another class of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory substances. Although both nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents reduced the baseline Isc, this effect on baseline is significantly more pronounced in the flufenamate-treated tissues compared to indomethacin. Furthermore both drugs differ in their capacity to inhibit secretagogue-induced Isc. Flufenamate inhibits the peak in Isc induced by carbachol and completely suppresses the long-lasting decay in Isc during the late phase of the carbachol-induced secretion (Figure 1), whereas indomethacin does not affect the peak phase at all (Strabel & Diener, 1995). In addition flufenamate inhibited the forskolin-induced Isc in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2) which was not observed for indomethacin. Therefore, the antisecretory effect of flufenamate cannot be caused by the inhibition of cyclo-oxygenases.

The inhibitory effect of flufenamate on Cl− channels published for other tissues was also observed in the rat colon. Flufenamate blocked the Isc induced by a mucosally directed Cl− gradient after depolarization of the basolateral membrane under unstimulated conditions and after stimulation of the adenylate cyclase with forskolin (Figure 5), confirming recently published patch-clamp data (Frings et al., 1999). The inhibition of Cl− conductances by flufenamate was also described for T-Lymphocytes (Schumacher et al., 1995), avian salt gland cells (Martin & Shuttleworth, 1994) and in Xenopus oocytes (Weber et al., 1995). Flufenamate shares this action with two other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ibuprofen and salicylic acid, which both inhibit cyclic AMP-mediated Cl− secretion in human colonic and airway epithelia (Devor & Schultz, 1998).

In different cell types flufenamate has been found to block non-selective cation conductances. In the human carcinoma cell line, HT29, flufenamate inhibits the non-selective cation conductance, which is activated after stimulation of purinergic receptors with ATP (Kerst et al., 1995). In the smooth muscle of guinea-pig ileum both flufenamate and 2-phenylaminobenzoic acid (DPC), structurally similar to flufenamate, blocked a cation channel, which was activated via stimulation of muscarinic receptors (Chen et al., 1993). In the rat exocrine pancreas flufenamate inhibited a non-selective cation channel with a single channel conductance of 27 pS. Half maximal inhibition was observed at a concentration of 10−5 mol l−1; the opening of the channel was blocked almost completely at 5•10−5 mol l−1 (Gögelein et al., 1990). Other cell lines, i.e. the cystic fibrosis pancreatic duct cell line CFPAC-1 (Schumann et al., 1994) or mouse fibroblast LM (TK−) (Weiser & Wienrich, 1996), also exhibited a flufenamate-sensitive Ca2+ entry pathway.

Recently we showed that a store-operated, lanthanide-sensitive, non-selective cation conductance is involved in the regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration in rat colonic epithelium (Frings et al., 1999). As is depicted in Figure 4, La3+ blocked the forskolin-induced Isc, indicating that a non-selective cation conductance is necessary to maintain cyclic AMP-mediated Cl− secretion. At first glance flufenamate exerted a similar effect (see Figure 2). However, the effect of flufenamate is very likely due to the inhibition of the apical Cl− conductance since some differences between La3+ and flufenamate emerged. In whole-cell experiments K+ and Cl− currents were suppressed by replacement of both ions with non-permeable ions. When the non-selective cation conductance was activated by a high intracellular concentration of EGTA, flufenamate induced a depolarization of the membrane and not a hyperpolarization as one should expect if the drug blocks non-selective cation channels. The depolarization was due to an increase of inward current, which, under the experimental conditions chosen, can only be caused by an influx of Na+ and Ca2+ across the non-selective cation conductance since K+ and Cl− currents were suppressed by replacement of both ions with non-permeable substitutes. These results suggest that flufenamate causes a stimulation rather than an inhibition of this pathway. In addition, flufenamate does not decrease the intracellular Ca2+ concentration under basal conditions and after stimulation with carbachol, but in contrast elevates it as shown by fura-2 experiments (Figure 9). A similar paradox effect of flufenamate on the basal intracellular Ca2+ concentration was already observed in the mouse mandibular cell line ST885 (Poronnik et al., 1992), where flufenamate has been shown to stimulate the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. In rat liver, the stores from which flufenamate releases Ca2+, are the mitochondria (McDougall et al., 1988). A possible explanation for the increase in membrane inward current induced by flufenamate may therefore be a further depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores, which in turn activates the non-selective cation conductance. Taken together, the reversal potential of the flufenamate-sensitive current, the ionic dependence, the fura-2 data, all these results argue against an inhibitory effect of flufenamate on the non-selective cation conductance in rat distal colon.

The data concerning a third conductance, which might serve as site of action of flufenamate, i.e. the cellular K+ conductance, were at first glance confusing since both an inhibition and an activation were observed (see Figures 6, 7 and 8). The inhibition of a basolateral K+ conductance by flufenamate was demonstrated by Ussing-chamber experiments with apically permeabilized membranes (Figure 6b). Flufenamate decreased the nystatin-induced K+ current in the presence of a serosally directed K+ gradient, indicating an inhibition of basolateral K+ conductances. The equivalent for this inhibition in intact tissue at the cellular level was the blockade of a K+ current leading to a depolarization, which was observed in four out of 11 crypt cells (Figure 8). Similar actions have been described for the structurally related compounds DPC on a basolateral, Ba2+-sensitive 23 pS K+ channel in human distal colon crypt cells (Lomax et al., 1996) and ibuprofen on basolateral K+ conductances in the human colonic cell line, T84 (Devor & Schultz, 1998). Another example for an inhibitory action of flufenamate on K+ conductances is the mouse fibroblast cell line, LM (TK−) (Weiser & Wienrich, 1996).

However, the main action observed of flufenamate on K+ currents during the whole-cell patch-clamp experiments was the activation of a K+ conductance. In seven out of 11 cells flufenamate hyperpolarized the membrane and increased the whole-cell outward current (Figure 7). Similar effects were described for rabbit corneal epithelium (Rae & Farrugia, 1992) and for jejunal circular smooth muscle (Farrugia et al., 1993a,1993b). It is unknown whether this stimulation of the K+ conductance is caused by the increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration observed in the fura-2 experiments (Figure 9a). Another possibility may be a direct interaction of the drug with K+channels as it has been shown for another fenamate, mefanamic acid, which stabilizes the ISK K+ channel in an open state (Busch & Suessbrich, 1997). Most of the whole-cell recordings, where the activation of a K+ conductance was measured, were performed at the lower part of the crypt, which might suggest that a gradient of the cells along the longitudinal axis of the crypt may also determine, whether cells responded with an activation or an inhibition of K+ permeability after administration of flufenamate.

In the Ussing chamber experiments, the dominant effect of flufenamate was a decrease in Isc consistent with the inhibition of Cl− and K+ channels. However, under Cl−-free conditions, flufenamate induced a transient increase in Isc (in six out of eight tissues), which preceded the long-lasting decrease in Isc. Consequently, when the inhibitory action of flufenamate on the apical Cl− conductance is eliminated, the stimulation of a basolateral K+ conductance also has a correlate in intact tissue. The activation of a K+ conductance may also be the reason for the transient increase in Isc observed, when flufenamate was administered during the plateau-phase of the current stimulated by CPT–cyclic AMP (Figure 3) and by forskolin (see Figure 4).

The last surprising action of flufenamate was the inhibition of a Na+–K+-ATPase as indicated by data obtained with apically permeabilized membranes (Figure 6c). This result was supported by uptake experiments. Under basal, i.e. unstimulated conditions, the basolateral Na+–K+-2 Cl− cotransporter constitutes only a minor fraction of the total basolateral uptake of 86Rb+ (Diener et al., 1996), a marker for K+. Uptake by the cotransporter gets only prominent, if the tissue is stimulated to secrete Cl− via the cyclic AMP-pathway (Diener et al., 1996), although this effect failed to reach statistical significance in this series of experiments, probably due to the shorter uptake period compared to the previous investigations. As the only transporter beside the cotransporter, which is able to move K+ from the serosal compartment into the cell is the Na+–K+-pump, these results together with the nystatin data (Figure 6c) strongly suggest that flufenamate has an inhibitory action on the Na+–K+-ATPase. Flufenamate is known to inhibit the mitochondrial synthesis of ATP via uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation (for references see McDougall et al., 1988). Consequently, a decrease in the intracellular ATP concentration may underlie the observed reduction in pump current.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that flufenamate possesses multiple action sites in the rat colon: the apical Cl− conductance, basolateral K+ conductances and the Na+–K+-ATPase. Qualitatively similar results were observed in the proximal compartment of the colon (data not shown). Consequently, the antisecretory action of this drug is not restricted to a single part of the large intestine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof Dr W. Clauß, Institut für Tierphysiologie, Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen for the opportunity to perform the fura-2 experiments in his laboratory and for the helpful advice. The contributions of Mrs B. Brück, D. Marks, A. Metternich, J. Murgott, B. Schmidt and E. Haas are gratefully acknowledged. Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant Di 388/3-4.

Abbreviations

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- DPC

2-phenylaminobenzoic acid

- EDTA

ethylene diamino tetraacetic acid

- EGTA

ethyleneglycol bis-(β-aminoethylether) N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- Gluc

gluconate

- Gt

tissue conductance

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-2-ethansulphonic acid

- Isc

short circuit current

- NMDG

N-methyl-D-glucamine

References

- BLEICH M., RIEDEMANN N., WARTH R., KERSTAN D., LEIPZIGER J., HÖR M., VAN DRIESSCHE W. , GREGER R. Ca2+ regulated K+ and nonselective cation channels in the basolateral membrane of rat colonic crypt base cells. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1996;432:1011–1022. doi: 10.1007/s004240050229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BÖHME M., DIENER M. , RUMMEL W. Calcium- and cyclic-AMP-mediated secretory responses in isolated colonic crypts. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1991;419:144–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00373000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSCH A.E. , SUESSBRICH H. Role of ISK protein in the IminK channel complex. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:26–29. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALDWELL R.A., CLEMO H.F. , BAUMGARTEN C.M. Using gadolinium to identify stretch-activated channels: technical considerations. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:C619–C621. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN S., INOUE R. , ITO Y. Pharmacological characterization of muscarinic receptor-activated cation channels in guinea-pig ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:793–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVOR D.C. , SCHULTZ B.D. Ibuprofen inhibits cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-mediated Cl− secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:679–687. doi: 10.1172/JCI2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIENER M., BRIDGES R.J., KNOBLOCH S.F. , RUMMEL W. Neuronally mediated and direct effects of prostaglandins on ion transport in rat colon descendens. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1988;337:74–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00169480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIENER M., EGLÈME C. , RUMMEL W. Phospholipase C-induced anion secretion and its interaction with carbachol in the rat colonic mucosa. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;200:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90581-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIENER M., HUG F., STRABEL D. , SCHARRER E. Cyclic AMP-dependent regulation of K+ transport in the rat distal colon. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1477–1487. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARRUGIA G., RAE J.L., SARR M.G. , SZURSZEWSKI J.H. Potassium current in circular smooth muscle of human jejunum activated by fenamates. Am. J. Physiol. 1993a;265:G873–G879. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.5.G873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARRUGIA G., RAE J.L. , SZURSZEWSKI J.H. Characterization of an outward potassium current in canine jejunal circular smooth muscle and its activation by fenamates. J. Physiol. 1993b;468:297–310. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRINGS M., SCHULTHEISS G. , DIENER M. Electrogenic Ca2+ entry in the rat colonic epithelium. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1999;439:39–48. doi: 10.1007/s004249900159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GÖGELEIN H., DAHLEM D., ENGLERT H.C. , LANG H.J. Flufenamic acid, mefanamic acid and niflumic acid inhibit single nonselective cation channels in the rat exocrine pancreas. FEBS Letters. 1990;268:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80977-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GÖGELEIN H. , GREGER R. A voltage-dependent ionic channel in the basolateral membrane of late proximal tubules of the rabbit kidney. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1986;407 Suppl 2:S142–S148. doi: 10.1007/BF00584943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GÖGELEIN H., SCHLATTER E. , GREGER R. The 'small' conductance chloride channel in the luminal membrane of the rectal gland of the dogfish (Squalus acanthias) Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1987;409:122–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00584758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRYNKIEWICZ G., POENIE M. , TSIEN R.Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HWANG T., NAGEL G., NAIRN A.C. , GADSBY D.C. Regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl channel by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:4698–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INSEL P.A.Analgesic-antipyretics and antiinflammatory agents: Drugs employed in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and gout The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 1990Pergamon Press, Elmsford: New York; 638–681.8. (eds) Goodman & Gilmans [Google Scholar]

- KERST G., FISCHER K.G., NORMANN C., KRAMER A., LEIPZIGER J. , CREGER R. Ca2+ influx induced by store release and cytosolic Ca2+ chelation in HT29 colonic carcinoma cells. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1995;430:653–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00386159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMAX R.B., WARHURST G. , SANDLE G.I. Characteristics of two basolateral potassium channel populations in human colonic crypts. Gut. 1996;38:243–247. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN S.C. , SHUTTLEWORTH T.J. Vasoactive intestinal peptide stimulates a cAMP-mediated Cl− current in avian salt gland cells. Regul. Pept. 1994;52:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDOUGALL P., MARKHAM A., CAMERON I. , SWEETMAN A.J. Action of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent, flufenamic acid, on calcium movements in isolated mitochondria. Biochem. J. 1988;37:1327–1330. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCNAMARA B., WINTER D.C., CUFFE J.E., O'SULLIVAN G.C. , HARVEY B.J. Basolateral K+ channel involvement in forskolin-activated chloride secretion in human colon. J. Physiol. 1999;519:251–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0251o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MESTRES P., DIENER M. , RUMMEL W. Storage of glycogen in rat colonic epithelium during induction of secretion and absorption in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;261:195–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00329452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAREKH A.B. , PENNER R. Store depletion and calcium influx. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:901–930. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORONNIK P., WARD M.C. , COOK D.I. Intracellular Ca2+ release by flufenamic acid and other blockers of the non-selective cation channel. FEBS Letters. 1992;296:245–248. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80296-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAE J.L. , FARRUGIA G. Whole-cell potassium current in rabbit corneal epithelium activated by fenamates. J. Membr. Biol. 1992;129:81–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00232057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULTHEISS G. , DIENER M. Regulation of apical and basolateral K+ conductances in the rat colon. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:87–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUMACHER P.A., SAKELLAROPOULOS G., PHIPPS D.J. , SCHLICHTER L.C. Small-conductance chloride channels in human peripheral T lymphocytes. J. Membr. Biol. 1995;145:217–232. doi: 10.1007/BF00232714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUMANN S., GREGER R. , LEIPZIGER J. Flufenamate and Gd3+ inhibit stimulated Ca2+ influx in the epithelial cell line CFPAC-1. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1994;428:583–589. doi: 10.1007/BF00374581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH G., WARHURST G., LEES M. , TURNBERG L. Evidence that PGE2 stimulates intestinal epithelial cell adenylate cyclase by a receptor-mediated mechanism. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1987;32:71–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01296690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRABEL D. , DIENER M. Evidence against direct activation of chloride secretion by carbachol in the rat distal colon. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;274:1814–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00728-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER W.M., LIEBOLD K.M., REIFARTH F.W. , CLAUSS W. The Ca2+ induced leak current in Xenopus oocytes is indeed mediated through a Cl− channel. J. Membr. Biol. 1995;148:263–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00235044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISER T. , WIENRICH M. Investigations on the mechanism of action of the antiproliferant and ion channel antagonist flufenamic acid. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353:452–460. doi: 10.1007/BF00261443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU X., TSAI T.D., WANG J., LEE E.W. , LEE K.S. Modulation of three types of K+ currents in canine coronary artery smooth muscle cells by NS-004, or 1-(2′-hydroxy-5′-chlorophenyl)-5-trifluoromethyl-2(3H) benzimidazolone. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:362–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]